Introduction

The Counter Reformation, also known as the Catholic Reformation, was about a hundred year period in Europe that aimed towards a resurgence of the Catholic Church in a new light that would draw followers and the faithful back to the heart of the church. The Counter Reformation came about at the same time as the Protestant Reformation in the mid-16th century and into the 17th century. The Catholic church was looking to brighten its appearance after the church was exposed of various financial abuses and cardinal corruption. The goal was to revamp the look of the church and bring back focus to the religious importance and values of being Catholic. At the center of the reforms were arts including literature, painting, architecture, and music to raise religious consciousness during this time. Music of the Catholic Church was a huge part of the art and cultural changes that would come about during the Counter Reformation. While the musical changes and decisions took place in various parts of Europe, England found itself at the same level with these changes and implemented them in their own church, despite any lash back from Protestant reformers. The musical changes that took place in the Counter Reformation were changes that set the precedent for church music in years to come of the 17th and 18th centuries, even affecting the church music heard in Catholic masses around the world today.

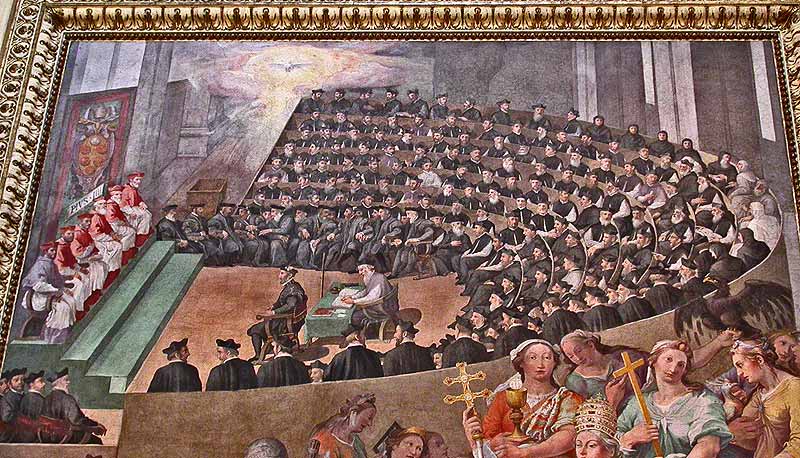

Council of Trent

Overview

The Council of Trent was a church council made up of cardinals that met in Italy to discuss reforms that would be taking place in response to the issues that Pope Paul III saw needed to be implemented to draw people back to the heart of the church. “Trent hosted the council in three distinct periods that stretched over eighteen years—1545–1547, 1551–1552, and 1562– 1563” (O’Malley). The third period was the period in which the most amount of people were a part of the council actively, about 200 members made up the council. The third period was also the period in which the issue of music in the church was discussed in the Council of Trent (O’Malley). The 22nd Session of the Council of Trent that took place on September 17, 1562, included a brief portion of discussion titled “Decree on the Sacrifice of the Mass”. The decisions that came out of the Council of Trent were vital to the sacred culture of the church for the century to follow the Counter Reformation.

Prior to the Reformation, Catholic Church music throughout Europe was known for its beautiful and ornate sounds, including many instruments and various voices singing at once. England had always had a unique sound to its church music as compared to the rest of Europe, sticking closely to its roots. The music played in England catholic churches included a mix of old traditional sounds in religious music and an intricate blend of styles of elaborate musical patterns and dynamics. Writers of music would compose extremely difficult songs filled with complicated combinations of musical intonation. (Kennemur). Many of the songs that were sung in churches were actually borrowed tunes from the secular melodies, the lyrics to the songs were changed into religious meanings and sung together at a service. It was actually church goers that made certain songs and styles of music well known since attending church was something that a vast majority of people tended too no matter what domination of Christianity (Kennemur). The popular secular songs, simply underwent lyrical changes so that the texts were appropriate for church and corresponded to biblical passages.

Once the Catholic Reformation took flight, the artist based music of the church prior to the reformation was undergone by some criticism, trying to make it a more “worship-friendly form of music” (Kennemur). As you explore this webpage, you will see the ways in which critics tried to reform the upbeat tunes into clear lyric based worship hymns as well as the way in which composers tried to reach a compromise between clear worshiping words and stylistic musical patterns of the past.

In England, specifically, soon after Mary takes the throne, “the catholic mass and late henrican music and ceremonial was reestablished throughout England…” (Willis). By the time Mary had died, the Catholic music Restoration was nearly widespread in many areas and aspects of the English Catholic church (Willlis).

In the 17th and 18th centuries in England, Catholic churches heard the polyphony and clear articulated sacred words that were composed during the time of the Counter Reformation. Changes took place in Catholic Church music all throughout Europe during the Counter Reformation and carried over into the way that the Catholics practiced their religion in the late 1600s and 1700s as the new changes took place. The new practices were tweaked and implemented in different ways in the 17th and 18th century as people became accustomed to the new styles of church music.

Amy Kennemur, “Music in the Church: Pre-Reformation, Post-Reformation, and Today.”

Concerns and Complaints Received by the Council of Trent

The council’s discussion of music was in regard to complaints about too much of a focus on secular portions of church music y neglecting the written text, the attitudes of church singers, and too many instruments and voices being used in church as a distraction from the meaning of the songs (May). There were also complaints on “the lack of liturgical sensibility on the part of organists, who played dances, displayed their skill, extended their playing to improper lengths, and so interfered with worship” (Fellerer). Although there were other discussions at the 22nd council, the fact that music was part of the discussion shows just how pressing of an issue this was in the Catholic Church and its effort to better itself.

Council of Trent’s Ruling on Music

The Council of Trent issued its opinion and statement on music reformation in the church in a transparent, yet obscure way for the churches to interpret as they wish. There is much controversy over the exact ruling of the council upon this meeting, though it is clearly understood that the council agreed that there is in fact a need for music in the mass. Much of the ruling itself, however, was not explicit and left to the interpretation of the individual church. In Canon 8, the council makes its declaration regarding music in the church: “Everything should be regulated so that the Masses, whether they be celebrated with the plain voice or in song, with everything clearly and quickly executed, may reach the ears of the hearers and quietly penetrate their hearts” (Monson). The Council makes it known that if music is to be sung, it needs to be clear what the text is in one way or another. It continues, “In those Masses where measured music and organ are customary, nothing profane should be intermingled, but only hymns and divine praises. If something from the divine service is sung with the organ while the service proceeds, let if first be recited in a simple, clear voice…” (Monson). If music is to be used in an intricate manner then the texts need to be made clear. The Council of Trent over all ruling emphasizes the necessity of the church music prioritizing religious value conveyance over artistic conveyance, yet it does not specifically ban the two from being combined in some way or another. Much of the council’s ruling is taken differently by each church in each nation throughout Europe, including England.

Thomas Tallis

Overview

Thomas Tallis was an English Counter Reformation composer who aimed to create pieces that reflected stylistic compromises between the reforms emphasized by the council and the artistry of catholic church music. He was born in Kent in the early 1600s, as there is no exact record of his early life and birth. It is known that he began coming into contact with some of England’s greatest composers while at the church at St. Mary-at-Hill where he was an organist (Paul, Allison). Tallis began to leave his mark on English church music while he was an organist and teacher of keyboard and composition at the royal household serving under Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary Tudor, and for more than half of the reign of Elizabeth I (Paul, Allison). It is said that during the mid-1600s, Tallis presented compositions of new vocal polyphony for the royal masses in England, through this Tallis earned himself a reputable name. He spent a great amount of time constructing new pieces of music that incorporated various voices, while keeping the meaning and words of the religious songs clear.

While Tallis was earning himself a reputable name, he also wanted to make a greater source of income, so he eventually asked the queen for additional income. The queen granted him this through the permission of “an exclusive license to print and publish music, the letters-patent issued for this purpose being among the first of their kind in the country” (Paul, Allison). Yet again, Tallis is becoming an influential part of English Catholic Reformation history. Tallis’s music could be heard in many English Catholic ceremonies especially throughout the late 1600s and into the 1700s.

Stylistic Writings and Works of Tallis

Almost all of Tallis’s works in this period of reformation were composed for five voices using low and high pitches and notes such as in his work, “Blessed are Those” (Paul, Allison). His writing mixed imitation of phrases with polyphony, which is a style of music that combines different parts of melodies and harmonies together at the same time of playing. His writings were reflective of the reformers wishes to have clear syllables being sung in music of the church. The styles that Tallis presented in his works were actually setting a foreground for the formal features that would become used in many service music pieces for several generations (Paul, Allison). Some of his famous works include: Hear the Voice and Prayer, If Ye Love Me, Remember Not, and O Lord in Thee Is my Trust. Overall, Tallis became a front-running composer for English counter reformation church music that set foundations for upcoming church musicians in centuries to follow the reformation.

William Byrd

One man who followed in the composition footsteps and had great influence form Tallis was the English William Byrd. Byrd would go on to be another great contributor to reformation of church music. He started off as a pupil of Tallis while at the Royal Chapel and grew to be a great companion to Tallis. Byrd is credited with having kept alive the tradition of the Latin motet style of church music in the Catholic Church post counter reformation. There were very few paces throughout England that the Latin motet could be heard in public as it was seen for private secular use rather than catholic liturgical use at the time of the reformation. The highly varied choral style known as a motet, was Byrd’s signature work, a daring one at the time of so many reformers demanding a band on secular use. Byrd was a known Catholic and was protected by the Queen Mary herself along with Tallis. The publishing license given to Tallis was also shared with Byrd. Due to his open Catholic practice and efforts in the church, he was persecuted for Catholic activities in 1593, but the Queen granted him her protection and halted the persecutions under her order (Kerman, McCarthy).

After Byrd and Tallis’s contributions to the musical society, “Piety,music, and the political need for constant visibility combined in a yearly, cycle of state visits to churches, monasteries, and convents, [would] court calendars and the newspapers of the day reported to the larger world” (Page).

Women and Music During and After the Counter Reformation

Overview

After the Counter Reformation, revival of the culture of the church caused courts to take an interest in convents around Europe. The Augustinian convent of St. Jakob, for example, had let out a mass production of great music by the late 1600s(Page). Vienna was one of the most flourishing cities for convents of nuns who wanted to create music. Around the end of the seventeenth century, “cloistered nuns regularly heard excellently performed church music, and had a fine model to emulate in their own musical efforts” (Page). On the other hand, Italian convents were under tough restrictions on creating music and accessing musical training as well as disproving of polyphonic compositions such as the ones created by Byrd and Tallis.

Music in Viennese Convents

The precise location of convents in Vienna near Jesuit schools and colleges allowed the nuns to have easy access to musical educations, an activity that was actually encouraged by the Catholic church in Vienna. The musical encouragements of the time were step forward for nuns (and women) in Vienna, encouraging them to embellish on the musical traditions of the church, “Musicians from St. Stephen’s performed at several convents on important feast days, and monks and priests from the monasteries and colleges tended to the spiritual needs of the nuns” (Page). There were a number of convents that encouraged musical practices amongst its nuns, such as taking up instruments, and even providing them with musical training. Three convents in Vienna following Counter Reformation, in the 1720s, were even asked to play for the imperial family. St. Jakob auf der Hülben, St. Agnes zur Himmelpforte, and St. Laurenz were three convents that were highly recognized for Counter Reformation musical capabilities (Page). Music was a way for women to become and inspiration and leave a lasting legacy that was hard to leave at the time.

Isabella Leonarda

Born to wealthy Italian parents in 1620, Isabella was sent to a convent to study when she was 16, like many wealthy Italian Catholic families did at the time. At the convent her musical skills were embraced and she began to compose. She was one of the most influential women composers in the late 1600s throughout Europe, “She composed throughout her life and from the 1670s on, her music was regularly published, to a total of 20 volumes” (Johnston). Her musical abilities to compose according to the changes of the Counter Reformation, gave her a step into earning higher status. While at her Ursuline Convent, she earned the title of madre (1676), superiora (1686), madre vicaria (1693), and consigliera (1700) holding leading positions in the convent (Women’s Sacred Music Project). In addition, she was a music teacher at the convent where she taught other nuns how to play her compositions. Leonarda was creating music that followed the guidelines set out by the Counter Reformation and setting an example for other nun composers at the time. Her “intricate use of harmonies is one example of her influence in the cultivation of polyphonic music at Sant’Orsola, as many other Italian nun composers were doing at their own convents during the same period” (Women’s Sacred Music Project).The harmonies she wrote and polyphony she promoted was all according to the changes that took place during the Counter Reformation as she kept a heavy focus on text as well. Interestingly enough, Leonarda’s pieces were meant to be performed by the nuns of Sant’Orsola, but when published they were sold to and for choirs of men and boys (Women’s Sacred Music Project). Leonarda was a catholic woman that embraced the cultural reforms of the Counter Reformation and had an impact on the music of the church regardless of men taking over performances in the 1700s. By the year 1700, Leonarda had composed nearly 200 works, however her popular works today were those created past when she turned 50, as that is when she began to publish her works. Today she is known as one of the most influential women composers of Europe for this era.

Women’s Sacred Music Project

Bibliography

- Burkholder, J. Peter. “Chapter 8: Sacred Music in the Era of the Reformation.” Concise History of Western Music, 3rd Edition . W.W. Norton and Company, Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

- Chapelle du Roi. “Tallis: Blessed are those that be undefiled.” Online video clip. YouTube. 11 November 2014. Web. 27 November 2016.

- “Counter-Reformation.” Counter-Reformation – New World Encyclopedia. 26 June 2013. Web. 27 Nov. 2016.

- Craig A. Monson. “The Council of Trent Revisited.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 55, No. 1 (2002).

- Fellerer, K. G., and Moses Hadas. “Church Music and the Council of Trent.” The Musical Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 4, 1953, pp. 576–594. www.jstor.org/stable/739857.

- “Isabella Leonarda, Nun and Baroque Composer, Featured at March 16 Concert.” Womens Sacred Music Project. Women’s Sacred Music Project, 2012. Web. 2 Dec. 2016

- Johnston, Blair. “Isabella Leonarda.” All Music. Rhythm One Group, 2016. Web. 2 Dec. 2016.

- Joseph Kerman and Kerry McCarthy. “Byrd, William.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music

- Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 1 Dec. 2016. <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/04487>.

- Kennemur, Amy. “Music in the Church: Pre-Reformation, Post-Reformation, and Today.” Social Studies Review 2001.Print.

- May, Patrick. “Music and the Counter-Reformation.” Music and the Counter-Reformation. 06 Dec. 2010. Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

- Mullett, Michael A. The Catholic Reformation. London: Routledge, 2002. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost).Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

- O’Malley, John W. Trent: What Happened At The Council. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2013. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

- Page, Janet K. Convent Music and Politics in Eighteenth-century Vienna. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014. Print.

- Paul Doe and David Allinson. “Tallis, Thomas.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online.

- Oxford University Press. Web. 30 Nov. 2016. <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/27423>.

- Willis, Jonathan P. Church Music And Protestantism In Post-Reformation England, Sites And Identities. Farnham, England: Routledge, 2010. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 30 Nov. 2016.

Originally published by the Museum of English Catholic Women Writers, Seton Hall University, as an Open Educational Resource. Republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.