Evolution is not “just a theory.” It is the framework by which biology makes sense. Its reality is written in stone, in genes, in living populations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Historical Tenacity of Misunderstanding

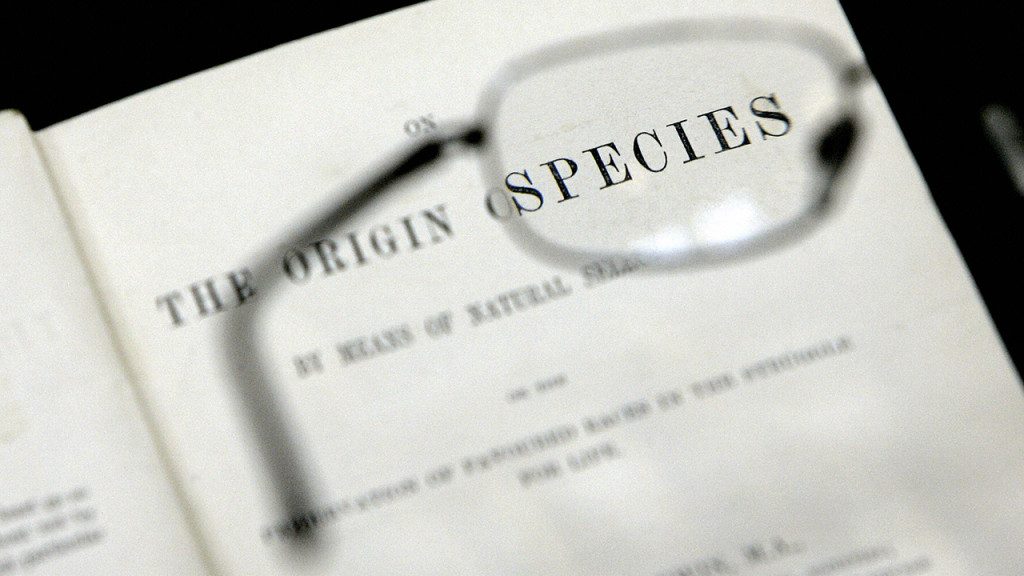

Few scientific theories have generated such sustained resistance as Charles Darwin’s account of natural selection. From the moment On the Origin of Species appeared in 1859, evolution became both a scientific cornerstone and a cultural lightning rod. Its explanatory power drew admiration, yet its challenge to traditional accounts of creation provoked waves of doubt, denial, and opposition.

Those opposed to evolution often recycle arguments that seem persuasive to the uninformed but collapse under scrutiny. They appeal to intuition rather than evidence, to rhetoric rather than reason. Phrases such as “just a theory” or “no transitional fossils” appear across decades with only slight variation, their persistence a testament not to their strength but to their cultural resonance.

To confront these arguments is not only to rehearse the evidence of biology but also to observe the human struggle to reconcile identity, faith, and science. The historian finds in them not simply failed critiques but artifacts of a cultural conflict that remains unresolved in many parts of the modern world.

“It’s Just a Theory”

Dayton, Tennessee, 1925. In the stifling heat of a small courtroom, Clarence Darrow leaned across the bench and asked William Jennings Bryan whether he believed the earth was created in six literal days. The trial of John Scopes had become a spectacle, but beneath the drama lay a refrain that has never died: evolution is “just a theory.”

This argument confuses two distinct meanings. In everyday language, “theory” implies guesswork or speculation. In scientific usage, it designates a comprehensive framework supported by evidence. Gravitation is a theory, as is relativity. Evolution, likewise, is a theory because it explains observed facts with rigorous coherence.1 To call it “just a theory” is not a critique but a misstep in translation.

The rhetorical durability of this phrase lies in its accessibility. It requires no knowledge of biology, only a semantic trick. Historians note its recurrence in debates over school curricula, where the phrase provides an air of skepticism while avoiding engagement with evidence.

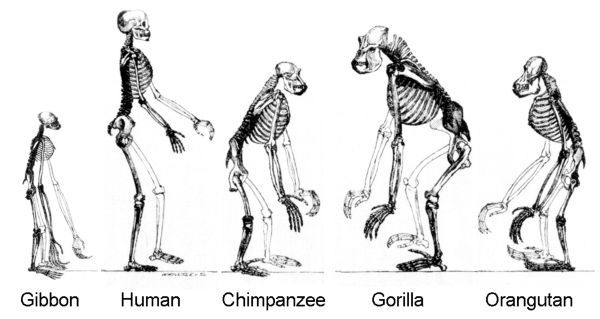

“If Humans Came from Monkeys, Why Are There Still Monkeys?”

The question, repeated endlessly, rests on a misunderstanding of common ancestry. Evolutionary biology does not claim that humans descended from modern monkeys. It asserts that humans and monkeys share a common ancestor, much as cousins share grandparents.2 To ask why monkeys still exist is akin to asking why German exists alongside English when both derive from a common linguistic root.

This misunderstanding flourishes because evolutionary time defies intuition. The tree of life is not a ladder with rungs of progress but a branching system in which species diverge and coexist. Humans did not replace monkeys; both lineages survived, adapting in different directions.

Yet this objection reveals more than ignorance. It also reflects a deep discomfort with kinship. To link humans with animals challenges anthropocentric hierarchies. Critics, consciously or not, resist the loss of human exceptionalism that common ancestry implies. The persistence of the argument lies in cultural identity as much as biological misunderstanding.

“The Second Law of Thermodynamics Disproves Evolution”

Opponents often invoke the Second Law of Thermodynamics, claiming that entropy makes increasing complexity impossible. Yet Earth both an open and closed sytem. It receives immense energy from the sun, allowing local decreases in entropy, as in the growth of crystals or the development of organisms.3

This argument is a classic example of borrowing scientific vocabulary without comprehension. By citing physics, critics seek authority, but their misuse betrays a lack of understanding. The irony is that life itself, in its very existence, demonstrates that complexity can and does arise within open systems.

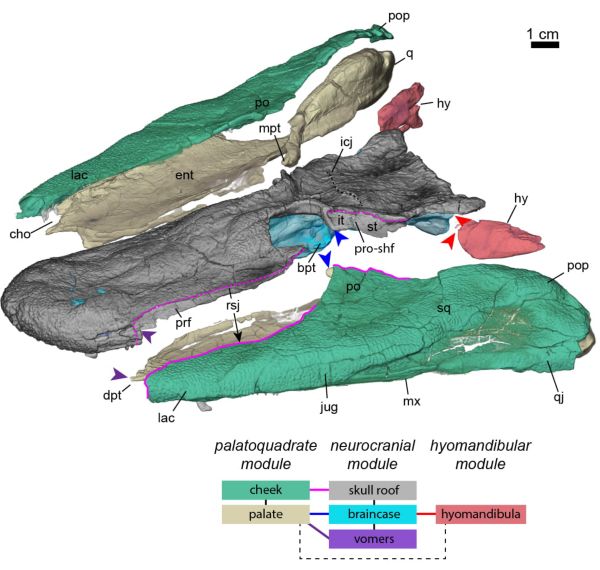

“There Are No Transitional Fossils”

Picture a limestone quarry in southern Germany, 1861. A fossilized feather is discovered, followed by a skeleton with both reptilian teeth and avian wings. Archaeopteryx stunned naturalists, offering a clear bridge between categories thought separate. It remains one of the most iconic transitional fossils.

The argument that no transitional fossils exist ignores a record that is increasingly rich. Beyond Archaeopteryx, discoveries such as Tiktaalik, a fish with proto-limbs bridging aquatic and terrestrial life, and hominin fossils from Australopithecus to Homo erectus provide abundant evidence of gradual change.4

The fossil record is fragmentary, but that is the nature of fossilization. Each new discovery fills gaps and refines understanding. Critics often demand an impossible perfection, dismissing the cumulative weight of partial yet compelling evidence.

Historians observe that this argument thrives because it exploits expectations of completeness. It suggests that unless every link is preserved, the chain is broken. But evolution is not a chain but a branching web, and the record, though incomplete, is sufficient to reconstruct its form.

“Evolution Cannot Create New Information”

Here, the language of information theory enters the debate. Critics claim that mutations can only destroy information, not create it. Yet biology demonstrates otherwise. Gene duplication produces redundant sequences, which may mutate and acquire new functions. Viral insertions and recombination events diversify genomes.5

In microbial experiments, entirely new capabilities evolve. E. coli in long-term laboratory studies developed the ability to metabolize citrate, a trait absent in its ancestral population. This is not the loss of information but the generation of a novel pathway.

The rhetoric of “no new information” gained traction in the late twentieth century, when creationist authors borrowed the language of computing. But in biology, information is dynamic. To reduce it to static code is to misrepresent its meaning.

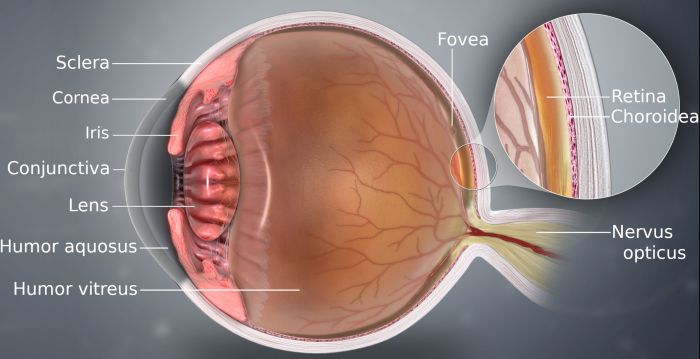

“Complex Organs Like the Eye Couldn’t Evolve Step by Step”

The eye, Darwin admitted, seemed at first a formidable challenge. Yet naturalists quickly recognized that living species display a spectrum of eye complexity, from simple light-sensitive patches in flatworms to sophisticated camera-like structures in vertebrates. Each stage offers an adaptive advantage.6

The “irreducible complexity” argument appeals to intuition: “I cannot imagine it, therefore it cannot be.” But incredulity is not evidence. The historical trajectory of the eye, documented across species, reveals not sudden perfection but gradual refinement.

“There Are No Beneficial Mutations”

Mutations are often harmful, but some confer clear benefits. Bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics. Insects develop resistance to pesticides. In humans, the sickle-cell trait protects carriers from malaria infection.7

The evidence extends beyond anecdotes. In long-term fieldwork on Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos, beak size shifted measurably within decades in response to drought, demonstrating beneficial variation under selection pressure. The laboratory confirms what the field observes: evolution is ongoing, adaptive, and at times swift.

To deny beneficial mutations is to deny not only evolutionary biology but modern medicine itself, for our understanding of pathogens and drug resistance rests precisely on these principles.

“Scientists Can’t Agree on Evolution”

Scientists disagree vigorously about details: the speed of evolutionary change, the role of developmental biology, or the relative importance of natural selection versus genetic drift. But they do not dispute the reality of evolution itself.8

This argument manipulates disagreement into doubt. By amplifying minor debates, critics suggest a wholesale collapse of consensus. Historians recognize the tactic: it mirrors strategies used in climate denial, where scientific debate about mechanisms is reframed as uncertainty about fundamental facts.

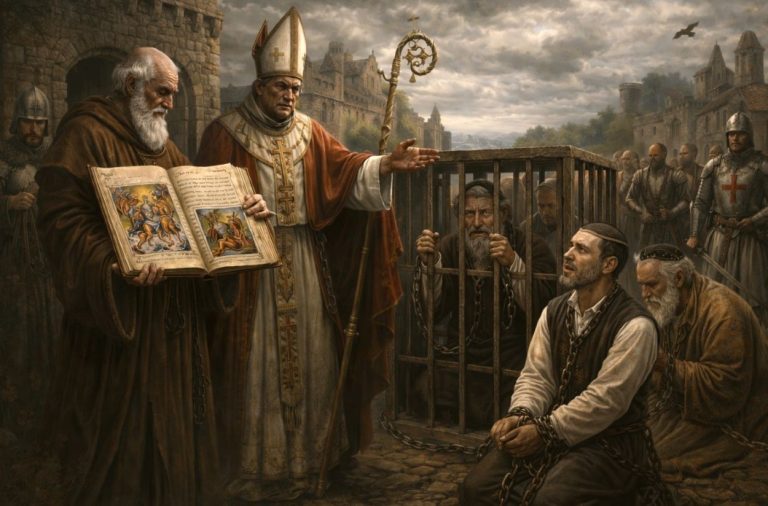

“Evolution Violates Scripture”

For some, the deepest objection is theological. A literal reading of Genesis, the Qur’an, or other sacred texts seems incompatible with common ancestry. This argument does not weigh fossils or genes but pits scriptural authority against scientific inquiry.

The historian notes how this objection shaped educational and political conflict, particularly in the United States. The Scopes Trial dramatized the clash, but controversies persist in curricula battles across states and countries. Scripture is not simply a text but a marker of identity, and evolution becomes a proxy for broader struggles between secular and religious authority.9

Yet not all faith traditions reject evolution. Many theologians have embraced evolutionary theory as a means of understanding divine creation. The Catholic Church, for example, has long acknowledged the compatibility of evolution with belief in God. Resistance is not universal but rooted in particular interpretations and contexts.

This section illustrates that the anti-evolutionary movement is not monolithic. Some opponents argue from science, however flawed, while others argue from revelation. To conflate them is to miss the complexity of cultural resistance.

“Nobody Has Ever Seen Evolution Happen”

Critics insist evolution is too slow to observe. Yet experiments and field studies prove otherwise. Richard Lenski’s long-term E. coli experiment, spanning tens of thousands of generations, documented adaptive mutations and the emergence of entirely new metabolic traits.10

In the natural world, speciation of cichlid fish in African lakes has been observed within human lifetimes. Evolution is not confined to deep time but is visible, measurable, and ongoing. The claim that it cannot be seen reflects more a refusal to look than a failure of evidence.

The Weight of Evidence

The cumulative evidence for evolution is overwhelming. Fossils trace gradual change across eras. Comparative anatomy reveals homologous structures linking diverse organisms. Embryology shows developmental pathways conserved across species. Genetics provides the deepest proof: the DNA of all life forms carries the imprint of common ancestry. Endogenous retroviruses, inserted in identical locations across genomes, testify to shared descent.

Direct observation further dismantles denial. Antibiotic resistance emerges in hospitals, pesticide resistance in agriculture, adaptive shifts in wild populations under climate stress. These are not metaphors but realities.

The historian sees in this abundance of evidence the futility of objection. Yet objections persist, not because evidence is lacking but because evidence is filtered through cultural frameworks. Scientific proof collides with identity, belief, and the comfort of intuition.

Evolution, then, is not only a biological theory but a cultural mirror. The persistence of doubt tells us less about fossils and genes than about the enduring human struggle to accommodate unsettling truths.

Conclusion: Persistence Amid Proof

Anti-evolutionary arguments survive not because they withstand scrutiny but because they are rhetorically simple and emotionally resonant. They persist in classrooms, pulpits, and political platforms, often divorced from the scientific realities they claim to address.

For the historian, they reveal the endurance of cultural narratives against the tide of evidence. For the scientist, they underscore that persuasion requires not only data but also narrative, pedagogy, and patience.

Evolution is not “just a theory.” It is the framework by which biology makes sense. Its reality is written in stone, in genes, in living populations. Yet its acceptance is written in culture, where myths of doubt continue to circulate, testifying to the gap between knowledge and belief.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Stephen Jay Gould, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002), 65–70.

- Richard Dawkins, The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution (New York: Free Press, 2009), 133–137.

- Daniel C. Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 187–192.

- Neil Shubin, Your Inner Fish (New York: Pantheon, 2008), 23–31.

- Sean B. Carroll, Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 101–109.

- Richard Dawkins, Climbing Mount Improbable (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996), 83–92.

- Peter R. Grant and B. Rosemary Grant, 40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 54–61.

- Douglas J. Futuyma, Evolution (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2013), 14–19.

- Ronald L. Numbers, The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 201–209.

- Richard E. Lenski et al., “Long-Term Experimental Evolution in Escherichia coli. I. Adaptation and Divergence During 2,000 Generations,” American Naturalist 138, no. 6 (1991): 1315–1341.

Bibliography

- Carroll, Sean B. Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- Dawkins, Richard. Climbing Mount Improbable. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996.

- ———. The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. New York: Free Press, 2009.

- Dennett, Daniel C. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 2013.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2002.

- Grant, Peter R., and B. Rosemary Grant. 40 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Finches on Daphne Major Island. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Lenski, Richard E., Michael R. Rose, Suzanne C. Simpson, and Scott C. Tadler. “Long-Term Experimental Evolution in Escherichia coli. I. Adaptation and Divergence During 2,000 Generations.” American Naturalist 138, no. 6 (1991): 1315–1341.

- Numbers, Ronald L. The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Shubin, Neil. Your Inner Fish. New York: Pantheon, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.