What precisely was a ship painter in the ancient Mediterranean?

By Dr. Martin Galinier

Professor of Archaeology

Université de Perpignan

By Dr. Emmanuel Nantet

Professor of Archaeology

University of Haifa

Introduction

Ancient literary sources often mention the existence of ‘ship painters’. What did this expression mean exactly? Were these artists representing ships in their paintings, or were they craftsmen who were adorning ships? The reappraisal of these texts gives us the opportunity to consider the two different situations. Indeed, during the Hellenistic period there were a great deal of marine paintings displaying ships. Alongside these famous painters, the numerous craftsmen who were devoted to the adornment of ships remained anonymous. Only a very few of them could overcome the stigma attached to the label of ‘craftsman’ and produce paintings too: one such painter was Protogenes.

‘Painting ships’ (naves pingere), as Pliny the Elder said about the activities of the painter Protogenes (‘until the age of fifty he was also a ship painter…’),1 may have two meanings: the first is to adorn ships; the second consists of representing ships in paintings. During Alexander’s funerals, the painter Apelles—or his workshop—may have produced four panels adorning the hearse of the conqueror and celebrating the military power of the Macedonian. Among these depictions was his war fleet.2 However, this picture, linked to the event that defines the early Hellenistic period, is neither the first nor the only one to represent ships. This article will explore these two very different pictorial exercises over a long period of time.

Few artists are described as ‘ship painters’. As a prefect of the imperial war fleet in Misenum, Pliny knew ships very well. Therefore, in calling someone a ship painter, he might imply both artistic and technical expertise. We should therefore pay particular attention to the work of Protogenes. What precisely was a ship painter in the ancient Mediterranean?3

Naval Issues before the Reign of Alexander

The Ancient Greeks, as far as we can glean from textual evidence, had a close interest in the sea and its navigation. If Iliad includes ‘The Catalogue of Ships’,4 Odyssey often describes the sea as barren and bitter. When Ulysses is about to leave Circe, a long description is dedicated to the construction of his raft, to the choice of the timbers, to the techniques used (with Circe’s help).5 Likewise, when Ulysses arrives among the Phaeacians, he notices the harbour and the ships in this city to which Poseidon granted ‘the great gulf of the sea (…)’.6 The launch of the ship offered to Ulysses by the king of the Phaeacians, Alkinoos, is also accurately described using technical details.7

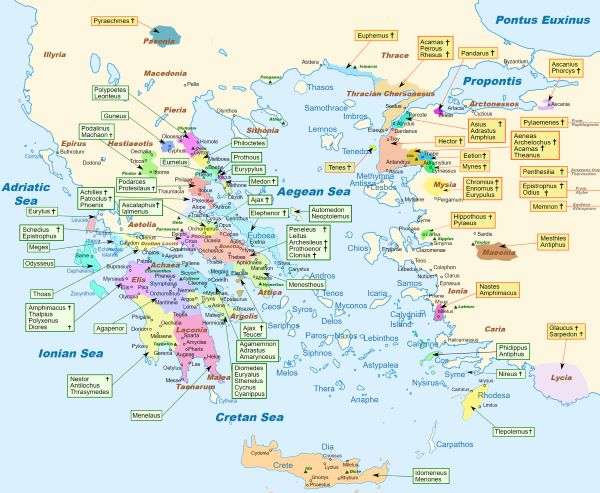

In the literary sources describing easel paintings, major works most of which have not survived to the present day, several references to maritime and naval representations can be found. Achilles’ shield, in Iliad depicts the god Ocean as the border of the world,8 as does Herakles’ shield in Hesiod (it also includes a ‘harbour with a safe haven’9). The ‘Catalogue of Ships’ enumerates all the black ships of the Achaeans taking part in the Trojan War.

Some artistic works are naturally inspired by the Homeric corpus. Indeed, the episode of the ‘Battle of the Greeks and the Trojans close to the ships’ is, according to Pausanias, described on the Chest of Kypselos,10 an ex-voto carried out to the temple of Hera in Olympia in the sixth century BCE. However, one of the most ancient literary references to paintings can be found in Herodotus. It is noticeable that this reference consists of an historical anecdote: the painting (graphsamenos) is a present offered by DariusI to Mandrokles of Samos, in order to reward him for having built the pontoon bridge used by the king to cross the ‘Thracian Bosporus’ (c. 513–512 BCE): it displayed the bridge itself, and it was at once consecrated, according to Herodotus, by Mandrokles to the Heraion of Samos.11 This gift was very political, emphasizing both Mandrokles’ science and DariusI’s power. When all is said and done, the political and honorary programme of Alexander’s hearse was not so far from the one that was displayed by Darius I’s painting.12

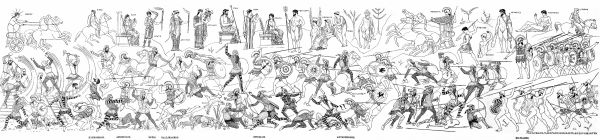

The great paintings of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE mention mostly ‘historical’ or ‘mythical’ representations.13 So Polygnotus of Thasos (470–440 BCE), in the Lesche of the Knidians in Delphi, displayed the Iliupersis and the departure of the Greek fleet with a great deal of verisimilitude:

‘On the ship of Menelaus they are preparing to put to sea. The ship is painted with children among the grown-up sailors; amidships is Phrontis the steersman holding two boat-hooks […] beneath him is one Ithaemenes carrying clothes, and Echoeax is going down the gangway, carrying a bronze urn’.14

His contemporary, Mikon, adorned the Stoa Poikile of Athens with a painting of the battle of Marathon, which mixed historical (Miltiades is emphasized)15 with heroic characters (the heroes of Marathon, Theseus, Athena, Herakles and the hero Echetlaeus are displayed on the side of the Athenian strategos),16 with ‘the Phoenician ships, and the Greeks killing the foreigners who are scrambling into them’.17

In both cases, these paintings, displayed in symbolic locations, combined the representation of heroes and historical examples. Both used the reference to reality (technical or historical) to lend credence to an event that held great importance for the client for whom the work was made. And in both cases, the narration aimed to exalt civic values, namely those of the cities of Knidos and Athens. The most important aspect was not the documentary realism of the painting, but its visual verisimilitude, which heightened the fame of the artist because it enabled him to convince the spectator of the ‘reality’ of the painting and of the ideological programme it promoted.18

Another useful genre, which was employed early in the fifth century, was that of allegorical painting: the hero Marathon, displayed in Mikon’s painting, is a good example of it. In the same period, Pausanias described a work by Panainos, Phidias’ nephew (c. 450–430 BCE), which adorned the balustrade of the statue of Zeus in Olympia: there various heroes could be found, as well as ‘[…] Hellas, and Salamis carrying in her hand the ornament made for the top of a ship’s bows’.19 Portraits appear in parallel: Miltiades by Mikon, and work by Parrhasios (c. 420–370 BCE): ‘He also painted […] a Naval Commander in a Cuirass’.20 Following the battle of Salamis in 480, the naval victory became a more and more popular theme.21

With the advent of Philip II and Alexander the Great, the question of the superiority of either ‘history’ or ‘myth’ was asked with more acuity. The conflict between the painter Apelles and the sculptor Lysippos is well known, the latter reproaching the former for having depicted, in one of his paintings, the hand of the king holding Zeus’ lightning, whereas he (Lysippos) portrayed the Conqueror with a spear ‘the glory of which no length of years could ever dim, since it was truthful and was his by right’.22 One of their contemporaries, Nicias of Athens (350–300 BCE), likewise emphasized historical representation, leaving mythical subjects to the realm of poetry. And he may have mentioned, among the noble subjects of history, that of naval battles:

‘The painter Nicias used to maintain that no small part of the painter’s skill was the choice at the outset to paint an imposing object, and instead of frittering away his skill on minor subjects, such as little birds or flowers, he should paint naval battles and cavalry charges where he could represent horses in many different poses […]. He held that the theme itself was a part of the painter’s skill, just as plot was part of the poet’s’.23

In the second century CE, Philostratus still praised the imitation of reality and explained that it was peculiar to painting: ‘For imitation […] in order to reproduce dogs, horses, humans, ships, everything under the sun’.24 Actually, these kinds of painted subjects hardly evolved from Alexander’s death to the time of imperial Rome, although after Actium more frequent representations of trade ships can be seen. This trend gained strength after Portus was founded by Claudius and the job of ‘feeding’ the plebs fell to the emperor. Few marine paintings have survived the great shipwreck of ancient works. At the very most two works by Pliny the Elder are worthy of mention. Theoros (c.320–280 BCE) would have painted ‘the Trojan War in a series of pictures’;25 and Nealkes of Sicyon (between the third and first century BCE), who:

‘[…] was a talented and clever artist, inasmuch as when he painted a picture of a naval battle between the Persians and the Egyptians, which he desired to be understood as taking place on the river Nile, the water of which resembles the sea, he suggested by inference what could not be shown by art: he painted an ass standing on the shore drinking, and a crocodile lying in wait for it’.26

There is no doubt that there must have existed many others:27 the Images by Philostratus, in the second century CE, provide an excellent example.28

Ship Painters

The activity of the painters who ‘were adorning the ships’ is more original. Since the Geometric period, ships were represented on Greek ceramics as having ornamental decoration on their bows:29 a circle with crossed lines, which quickly evolved to become the well-known apotropaic eye.30 These representations are frequent on Geometric and Orientalizing ceramics, and in the Attic works with black and red figures. This was the case with the naval battle that was represented on the Aristonothos krater (c. 675–650 BCE): one of the two ships bears an eye.31 In the classical period, the ram often took an animal shape, for example a ram shaped like a boar’s head,32 or a fish’s head.33 The difficulty lies in understanding whether, in the image, this animal shape is constructed by the metallic part (the ram) or by various techniques with additions of figurative details painted on wooden and metal structural elements. In other words: whether the shape is intrinsic to the object or whether it is created with the use of paint.

Euripides, in Iphigenia in Aulis, suggests an interesting change to the ‘Catalogue of Ships’ by Homer. Although it takes place in a heroic time, the action of the play should have reminded the contemporaries of the tragedian of a familiar reality. However, for Euripides, the ornamentation of the ships is statuesque, spectacular, and rather located astern:

‘I came to reckon and to behold

their wondrous ships,

to fill with pleasure

the greedy vision of my female eyes.

Holding the right flank

of the fleet

was the Myrmidon force from Phthia

with fifty swift ships.

In gilded images high upon their sterns

stood Nereids,

the ensign of Achilles’ fleet.

(…)Next to them

with sixty ships from Athens,

was encamped

Theseus’ son, who had the goddess Pallas

mounted on a chariot with winged steeds,

as the clear marker for his sailors.The Boeotians’ seagoing panoply,

fifty ships, I saw

blazoned with ensigns.

There was Cadmus

holding a golden serpent

aloft on the ships’ high sterns.

Leitus, one of the Sown Men,

led his naval armament.

[…]

From Pylos I saw

Of Gerenian Nestor

[…]

the ensign upon his sterns, bull-footed in appearance,

the Alpheus River, his neighbor’.34

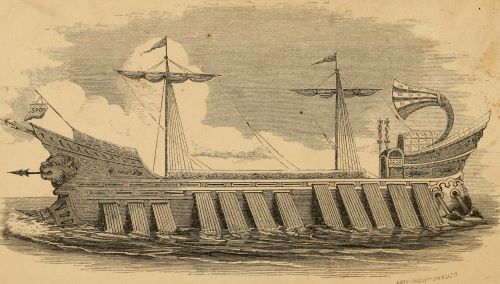

In the Hellenistic period, the painted ornamentation of the warships is documented by various representations such as the mosaics showing BerenikeII’s ram-shaped crown by Sophilos,35 or the fresco found in Nymphaeum and displaying a 1.2-metre-long ship bearing the name Isis.36 As for the Athlit ram, although it is not painted, it bears traces of its decoration.37

Ornaments in relief, rather than statuary, also appear on Greek coins, particularly those issued by the Lycian city of Phaselis, which, by the late fourth century, show staters with an eye at the bow and, above, the outline of a dolphin.38 Another coin, from the same city, displays the same ram, but with the head of a gorgon, and the outline of a cicada ‘in front’ of the ship.39 Yet another coin from Phaselis represents a radiate bust (Helios) is laid on the deck, above the ram with an eye and a dolphin below;40 or even a very beautiful detail of a ram with boar’s head.41 After the conquest of the harbour by Ptolemy I in 309 BCE, busts of the king and of Berenice (with diadems) are represented above the ram, laid on the deck.42 In the same period, the tetradrachm of Demetrios Poliorcetes, commemorating the victory of Salamis in 306, shows a winged Victory blowing a trumpet on the bow of a ship. The work was often compared to the Victory of Samothrace, but it does not show an actual ship scene: these elements are above all political symbols, referring to the authority that issues the coins,43 not necessarily depictions of real scenes. It is notable that these decorations are located at the bow, whereas Euripides located the ornaments astern: nevertheless, further documentary evidence indicates that the bow could indeed carry significant ornamentation.

One such example is the text written by Athenaeus of Naucratis, with its famous description of the Tessarakonteres, the giant ship of Ptolemy II Philopator, which specifies:

‘Wonderful also was the adornment of the vessel besides; for it had figures at stern and bow not less than eighteen feet high, and every available space was elaborately covered with encaustic painting; the entire surface where the oars projected, down to the keel, had a pattern of ivy-leaves and Bacchic wands’.44

The other ship belonging to the king, the Thalamegos, intended to sail along the Nile, included astern

‘[…] a frieze with striking figures in ivory, more than a foot and a half tall, mediocre in workmanship, to be sure, but remarkable in their lavish display. Over the dining-saloon was a beautiful coffered ceiling of cypress wood; the ornamentations on it were sculptured, with a surface of gilt’.45

Lastly, when discussing the giant ship of Hiero, Athenaeus mentions the external decoration: ‘outside, a row of colossi, nine feet high, ran around the ship; these supported the upper weight and the triglyph, all standing at proper intervals apart. And the whole ship was adorned with suitable paintings.’46

The ‘figures’ surrounded the ship on all sides: indeed, the size of the ship was similar to a floating palace.

Let us dwell for a moment on these ‘painted paintings’, these ‘drawings made of wax’ mentioned by Athenaeus. Ancient shipwrecks have not revealed much evidence of painted decoration.47 Except the Marsala shipwrecks,48 it is true that no shipwreck of a warship has been found. However, as Pliny the Elder explains, this kind of decoration was first lavished upon this kind of ship, surely because of its cost, and also because of the political significance of said decoration, which was not useful for a merchantman. Nevertheless, the prefect of the fleet at Misenum describes a change that occurred during his time:

‘Wax is stained with these same colours for encaustic paintings, a sort of process which cannot be applied to walls but is common for ships of the navy (classibus familiaris), and indeed nowadays also for cargo vessels (onerariis navibus)[…]’.49

From a technical point of view, these paintings on a ship are therefore associated with encaustic painting. Although he does not provide any dates for this innovation, Pliny points out that this technique was first used on wax and ivory, with a cestros; ‘later the practice of decorating battleships (classes pingi) was developed. There followed a third method, that of employing a brush when wax has been melted by fire; this process of painting ships (quae pictura navibus) is not spoilt by the action of the sun nor by saltwater or winds’.50 Then Pliny specifies:

‘A third of the white pigment is ceruse or lead acetate, the nature of which we have stated in speaking of the ores of lead. There was also once a native ceruse earth found on the estate of Theodotus at Smyrna, which was employed in old days for painting ships (navium picturas)’.51

The technique described was adapted to the environment for which the paintings were made, as were the materials used. This specialism, which was looked down upon, occurs on only two occasions in the history of Greek painting as established by Pliny the Elder: when two of those craftsmen managed to rise from the stigmatised occupation of ship painter to the rank of easel painter, and thus to make a name for themselves as artists.

The first was Protogenes of Caunus (300–240 BCE), from Rhodes. Apelles’ contemporary, he experienced rough start:

At the outset he was extremely poor, and extremely devoted to his art and consequently not very productive. The identity of his teacher is believed to be unrecorded. Some people say that until the age of fifty he was also a ship painter (naves pinxisse), and that this is proven because when, later in life, he was decorating the gateway of the Temple of Athene on a very famous site in Athens, (where he created his famous Paralus and Hammonias, which is also called the Nausicaa [two sacred ships of Athens] by some people), he added some small drawings of battleships in what painters call the ‘side-pieces,’ (parergia) in order to show from what origins his work had come, to arrive at the pinnacle of this glorious display.52

The location of this painting in the Propylaea, and the subject (the sacred triereis of Athens), show how significant Protogenes had become by the first half of the third century. One interpretation of Pliny’s words is that Protogenes was painting, not ships, but ex-votos representing ships. It is true that this practice existed in Antiquity,53 as evidenced by Latin sources. What was it?

Cicero clearly mentions the votive tablets that were offered in order to express gratitude to the protective deity after a storm:

You object that on occasion good men achieve successes; indeed, we latch on to those, and without any justification attribute them to the immortal gods. The opposite was the case when Diagoras, whom they call the Atheist, visited Samothrace, where a friend remarked to him: ‘You believe that the gods are indifferent to human affairs, but all these tablets (tabulis pictis) with their portraits surely reveal to you the great number of those whose vows enabled them to escape the violence of a storm, so that they reached harbor safe and sound.’ ‘That is the case’, rejoined Diagoras, ‘but there are no portraits (picti) in evidence of those who were shipwrecked and drowned at sea’.54

This practice is confirmed by Juvenal, who insists on its importance55 and describes another practice, associated this time with begging:

‘The person […] will now have to be satisfied with rags covering his freezing crotch and with scraps of food while he begs for pennies as a shipwreck survivor and maintains himself by painting a picture (picta) of the storm’.56

Was Protogenes a painter who specifically produced marine paintings?57 The expression used by Pliny (naves pingere) is not the same as Cicero’s or Juvenal’s (who mention tabula or tabella):58 the support of Protogenes’ paintings was therefore the ship herself, similar to the paintings of Herakleides the Macedonian (who lived around 168 BCE): ‘Heraclides of Macedon is also a painter of note. He began by painting ships (initio naves pinxit), and after the capture of King Perseus he migrated to Athens…’.59

As we know, the practice of painting with wax did not disappear.60 Indeed, the arrival of the ship of Cybele, Mother Goddess, in Rome, in 204 BCE, was celebrated two centuries later by Ovid:

‘[…] a thousand hands assemble, and the Mother of the Gods is lodged in a hollow ship painted in encaustic colours (picta coloribus ustis)’.61

Conclusion

The end of the Hellenistic period merged with the Roman period. A few artists perpetuated the maritime and historical paintings, like Androbios,62 while mural paintings developed too:63

[…] Spurius Tadius also, during the period of his late lamented Majesty Augustus, was cheated of his due, who first introduced the most attractive fashion of painting walls with pictures of country houses and porticoes […] rivers, coasts, and whatever anybody could desire, together with various sketches of people going for a stroll or sailing in a boat […] people fishing […]’.64

As in Greek verse, Latin poetry commemorates some memorable ship battles, such as Propertius who describes the battle of Actium:

Nor let it frighten you that their armada sweeps the waters with many hundred oars: the sea o’er which it glides likes it not. And all the Centaurs threatening to throw rocks borne by their prows will prove to be naught but hollow planks and painted scares.65

This ship decoration can be found on the marble frieze from the time of Claudius, evoking the battle of Actium, which shows Antony’s ship with a rearing Centaur as a figurehead (conversely, the Scylla of Augustus’ ship would have disappeared during a modern restoration).66 The Vatican Virgil still shows Aeneas’s ships with statues at their bow.67 As for the bronze ornaments of the Roman ships of Nemi, they are to a certain extent the monumental heirs of the wax figures of the Hellenistic ‘ship painters’.68

Appendix

Endnotes

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.101.

- Diodorus Siculus, 18.27: ‘the fourth, ships made ready for naval combat.’ In addition to a war fleet, a skit represented Alexander holding a sceptre surrounded by Macedonians and Persians; another with elephants mounted by Indians and Macedonians; and the third with horsemen.

- See primarily Reinach 1921. More recently, Rouveret 2017, 61–84.

- Homer, Iliad 2.5 Homer, Odyssey.

- 160–269. Pamphilus of Amphipolis (400–350) represented Odysseus on his skiff (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.76) On Odysseus’ craft, see Casson 1964, 61–64; Casson 1992, 73–74; Mark 1991, 441–45; Mark 1996, 46–48; Mark 2005, 70–96; Tchernia 2001, 625–31.

- Homer, Odyssey 7.35.

- Homer, Odyssey 8.50 and following verses: ‘[…] they drew the black ship down to the deep water, and placed the mast and sail in the black ship, and fitted the oars in the leathern thole-straps, all in due order, and spread the white sail. Well out in the roadstead they moored the ship […]’.

- Homer, Iliad 16.

- Hesiodos, The Shield of Heracles 207–08.

- Pausanias, 5.19.1. See Snodgrass 2001, 127–41.

- Herodotus, 4.88. The same Herodotus mentions, during the siege of Phocaea by Harpagus, ‘paintings’ in the city (Herodotus, 1.164), without any precision. On Mandrokles: West 2013, 117–28. Many wooden votive offerings representing ships were found in that very sanctuary: Kyrieleis 1980, 89–94; Kyrieleis 1993, 99–122,sp. 112. These numerous offerings of the Archaic period were certainly related the marine cult of Hera: see Fenet and Jost 2016.

- During the imperial period, Trajan also commissioned a representation of the bridge on the Danube. This work was conducted by his architect Apollodorus of Damascus, on his column including the bas-relief evidencing the conquest of Dacia (Coarelli 1999, 162, sc. 98–99). He also ordered carvings of several scenes of navigation, one of which showed him operating the ‘rudder’ of a warship (idem,78 sc.34), while others represented two pontoon bridges on the Danube (sc. 3 and 47).

- On this matter, see Hölscher 1973; Rouveret 1989, 129–61; and Linant de Bellefonds and Prioux 2017.

- Pausanias, 10.25.2. It is possible that Pausanias, who reads names inscribed on the table, has mistakenly identified the name Echoiax with one of the characters (Reinach 1921, reed. 1985, 93, note 3). About Polygnotus, see Cousin 1999, 61–103; and Hölscher 2015, 47–48.

- Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades 6.3.

- Pausanias, 1.16.

- Pausanias, 1.15.

- Höslcher 2015, 25: ‘L’une des tâches fondamentales dévolues aux images consiste à rendre ‘présents’ des personnes, des objets ou des événements qui se trouvent être absents in corpore’. And Höslcher 2015, 51: ‘De fait, toutes les déclarations des auteurs antiques portant sur l’art figuratif soulignent le caractère central de cette référentialité des images par rapport à la réalité’. Lastly Höslcher 2015, 53: ‘S’il est vrai que l’image est une construction, la réalité représentée dans l’image est également une construction’.

- Pausanias, 5.11.5.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.69.

- See Glasson 2014.

- Plutarch, Moralia, Isis and Osiris 24.

- Demetrius, On Style 76.

- Philostratus, Life of Apollonius 2.22.

- Pliny, Natural History 35.144 (representation that inspired the Tabulae Iliacae found in Rome?).

- Pliny, Natural History 35.142. It is worth noting that Aristotle, in Problems 23.6, laid down a pictorial rule that seems to have been followed: ‘[…] at any rate, painters paint rivers as pale, and the sea as blue.’ In ancient art, representations of the Nile were mostly unaffected by this classification: see for example in the mosaic of Palestrina, where the waters of the river are shown in blue.

- For example, Kydias of Kythnos (4th century BCE): ‘[…] for whose picture of the Argonauts the orator Hortensius paid 144,000 sesterces, and made a shrine for its reception at his villa at Tusculum.’ (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.130.) The painting might have inspired the name of the portico of the Argonauts in Rome, built by Agrippa (Cassius Dio, 53.27: ‘Meanwhile Agrippa beautified the city at his own expense. First, in honour of the naval victories he completes the building called the Basilica of Neptune and lent it added brilliance by the painting representing the Argonauts.’ About Jason, Martial, Epigrams 11.1.12 speaks of the ‘captain of the first ship’, ‘primae dominus carinae’). See also Hippys (Hellenistic period?): ‘Hippys for his Poseidon and his Victory.’ (Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35. 141).

- Philostratus, Imagines 1.19: ‘Les Tyrrhéniens’ (who took his inspiration from a myth of the Homeric Hymn to Dionysus): ‘Now the pirate ship sails with warlike mien […] And, in order that it may strike terror into those they meet and they may look to them like some sort of monster, it is painted with bright colours, and it seems to see with grim eyes set into its prow, and the stern curves up in a thin crescent like the end of a fish’s tail. As for the ship of Dionysus, it has a weird appearance in other respects, and it looks as if it were covered with scales at the stern, […] and its prow is drawn out in the semblance of a golden leopardess. Dionysus is devoted to this animal because it is the most excitable of animals and leaps lightly like a Bacchante.’

- For example, a fragment of a Geometric krater of the Dipylon Master (A. Louvre, 517): https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/cratere-fragmentaire; see in Basch 1987, 172, Fig. 353.

- About the prophylactic eyes in marble found on the Agora in the Tektas Burnu shipwreck, in the harbour of Zea, see Carlson 2009, 347–65. The traces of paint that remain on a few of them reveal that they were certainly painted.

- This vase was produced by a potter settled in Etruria: http://www.museicapitolini.org/fr/percorsi/percorsi_per_sale/museo_del_palazzo_dei_conservatori/sale_castellani/cratere_con_l_accecamento_di_polifemo_e_battaglia_navale).

- About an Attic dinos (Basch 1987, 212, Fig. 440; or 217, Fig. 453; 227, Fig. 472: cup signed by Nikosthenes, Louvre, F 123: https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/coupe-attique-de-type-figures-noires).

- Basch 1987, 221, Fig. 460. See also the very beautiful ram-shaped vases from Apulia, for example the one which is conserved in the Petit Palais (Paris), inv. ADUT 422 (on this matter, Ambrosini 2010, 73–115: the creation of these large vases in Magna Graecia would have resulted from the introduction of the cult of Cybele in Southern Italy by Athens).

- Euripides, Iphigenia at Aulis 231–76, trans. D. Kovacs.

- Daszewski 1985, 142–58, pl.A, 32.

- Basch 1985, 129–51.

- Casson and Steffy 1991.

- Item offered for sale in an auction in September 2016 (https://www.numisbids.com/n.php?p=lot&sid=2739&lot=18).

- Item offered for sale in an auction in September 2016 (https://www.numisbids.com/n.php?p=lot&sid=2739&lot=18).

- Bibliothèque nationale de France (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780665q).

- Bibliothèque nationale de France (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780671n). This item would be dated to the fifth century BCE; see Basch 1987, 297, Fig. 626. On the coinage issued by Phaselis: Heipp-Tamer 1993.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France (http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780658f).

- On these representations, see most recently Badoud 2018, 279–306.

- Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 5.204 a-b.

- Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 5.205c.

- Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 5.208b. There was an inscription too: ‘freshly charactered on its stout prow’ (Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 5.209d.). Rouveret (1989, 210–12) briefly mentions the ornamentation of these two giant ships. About these ships: Pomey and Tchernia 2006, 81–99; Castagnino Berlinghieri 2010, 169–88; Nantet 2016, 126–31.

- Although very rare, traces of painting have been identified on very few ancient shipwrecks, such as the Herculanum shipwreck, whose hull revealed a white line. Steffy 1985,519–21. The white line could have been a tonnage mark, even though this suggestion must be considered with caution, see Nantet 2016,75, 430–31, E58. The Pisa shipwreck also showed some traces of painting: Colombini et al. 2003, 659–74. Dyes have been found in some shipwrecks, such as the La Madrague de Giens shipwreck (Liou and Pomey 1985, 564) and a few others (see references in the same article). They were used for the reflection of the hull paintings. On the contrary, the dyes found on the Planier3 shipwreck should be considered as part of the cargo (Tchernia 1968–1970, 51–82.). The Gyptis, a replica of the Jules-Verne 9 shipwreck, was painted: Pomey 2014, 1333–57. Pomey and Poveda 2018, 45–56. For photos, see Pomey and Poveda 2015.

- Honor 1981.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.49.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.149. See also Pliny the Elder, Natural History 16.56: ‘We must not omit to state that among the Greeks also the name of ‘live pitch’ [zopissa] is given to pitch that has been scraped off the bottom of seagoing ships and mixed with wax—as life leaves nothing untried—and which is much more efficacious for all the purposes for which the pitches and resins are serviceable, this being because of the additional hardness of the sea salt.’ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 24.26: ‘Zopissa, as I have said, is scraped off ships, wax being soaked in sea brine. The best is taken from ships after their maiden voyage. It is also added to poultices to disperse gatherings.’ These lines reveal a few details about the technical operations of ship maintenance. On the use of pitch: Connan et al. 2002, 177–96; and Connan 2002, 2–9, who mention a mixing of pitch and wax that covered the surface of the planking of the Archaic hull of the Jules-Verne 9 shipwreck. More recently, pitch has been identified on the Arles-Rhône3 shipwreck, as it was used for luting, cf. Marlier 2014, 115–16.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.19. There would have been a confusion here with the cresa viridis (Dauzat 1997, 35, note 77). On wax as a technique used in painting and carving, see Bourgeois 2014, 69–80.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.101. About the Athenian warships, see Bubelis 2010, 385–411, Historia 59.4.

- And much later: Rieth and Milon 1981.

- Cicero, 3.89, trans. Walsh 1997.

- Juvenal, 12.25: ‘[…] a different kind of danger. Listen and pity him a second time. The rest is, admittedly, part of the same experience, terrible without doubt, but familiar to many, as all those shrines with their votive tablets (fana tabella plurima) indicate. Everyone knows that painters make their bread and butter from Isis.’

- Juvenal, 14.300.

- This was Reinach’s interpretation (1985, 399) of Pliny’s two texts dealing with the ‘ship painters’. Likewise, de Ridder (1915, 282–87), who connected in a series the ram-shaped bas-relief found in Rhodes (acropolis of Lindos) and the funerary steles of Rhenea.

- Plisecka 2011.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.135.

- See La Torre et al. 2011; Linant de Bellefonds et al. 2015.

- Ovide, Fasti 5.275–76.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.138: ‘Androbius painted a Scyllus Cutting the Anchor-ropes of the Persian Fleet.’

- Examples include the mural paintings of the temple of Isis in Pompei, currently displayed in the Archaeological Museum of Naples.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 35.116–117. On Roman painting in general (including Pliny), see Croisille 2005; and on the Roman collectors: Routledge 2012.

- Propertius, Elegies 4.6.50 and the following verses.

- Copy of the Medinaceli-Budapest bas-reliefs (Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées 2014, 292–95); see also Tomei 2017 (http://journals.openedition.org/mefra/4446): marble fragments show ships decorated with various carved characters. A gem conserved in the Berlin museum reveals a huge ship with the figure of a bull on her bow: was it a reminder of the Hiero’s Syracusia? (Basch 1987, 471, 474. Fig. 1070).

- Vatican, Latin manuscript 3225, folio XLII recto and XLIII verso (https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.3225/0001).

- Lastly on these ornaments: Wolfmayr 2013; Frielinghaus et al. 2017, 91–104.

Primary Sources

- ‘Coupe attique de type A à figures noires.’ (Kardianou-Michel, A.) Louvre. https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/coupe-attique-de-type-figures-noires.

- ‘Cratère fragmentaire.’ (Kardianou-Michel, A.) Louvre. https://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/cratere-fragmentaire.

- ‘Cratere con l’accecamento di Polifemo e battaglia navale.’ Musei Capitolini. http://www.museicapitolini.org/it/percorsi/percorsi_per_sale/museo_del_palazzo_dei_conservatori/sale_castellani/cratere_con_l_accecamento_di_polifemo_e_battaglia_navale.

- ‘Monnaie: Statère, Argent, Phasélis, Lycie. No. FRBNF41780665. IFN-8524144.’ BNF. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780665q.

- ‘Monnaie: Statère, Argent, Phasélis, Lycie. No. FRBNF41780671. IFN-8524150.’ BNF. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780671n.

- ‘Monnaie: Statère, Argent, Phasélis, Lycie. No. FRBNF41780658. IFN-8524137.’ BNF. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb41780658f.

- ‘Statère – Phaselis (4ème siècle av. J. C.).’ Numisbids. https://www.numisbids.com/n.php?p=lot&sid=2739&lot=18.

- Babbitt, F. C., trans. 1969. Plutarch. Moralia. Vol. 5. Isis and Osiris. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1936.

- Braund, S. M., ed. and trans. 2004. Juvenal. The Satires. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Cary, E., ed. and trans. 1955. Cassius Dio. Roman history. Vol. 6. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1917.

- Rolfe, J. C., trans. 1929. Cornelius Nepos. The Book on the Great Generals of Foreign Nations. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Evelyn-White, H. G., trans. 1959. Hesiodos. The Shield of Heracles. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1914.

- Fairbanks, A., trans. 1960. Philostratus. Imagines. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1931.

- Frazer, J. G., trans. 1967. Ovid. Fasti. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1931.

- Geer, R. M., ed. and trans. 1947. Diodorus Siculus. Vol. 9. The Library of History. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Douzat, P., ed. 1997. Pline l’Ancien, Histoire Naturelle. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Godley, A. D., trans. 1928. Herodotus. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1921.

- Goold, G. P., ed. and trans. 1990. Propertius. Elegies. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Gulick, C. B., ed. and trans. 1957. Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1928.

- Innes, D. C. ed. and trans. 1995. Demetrius. On Style. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library (based on W. Rhys Roberts).

- Jones, C. P., ed. and trans. 2005. Philostratus. Vol. 1. The Life of Apollonius of Tyana. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Jones, W. H. S., trans. 1959. Pausanias. Description of Greece. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1918.

- Jones, W. H. S., trans. 1965. Pausanias. Description of Greece. Vol. 4. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1935.

- Jones, W. H. S., trans. 1966. Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Vol. 7. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1956.

- Jones, W. H. S., and h. A. Ormerod, trans. 1966. Pausanias. Description of Greece. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1926.

- Kovacs, D., ed. and trans. 2002. Euripides. Vol. 6. Iphigenia at Aulis. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Mayhew, R., ed. and trans. 2011. Aristotle. Vol. 9. Problems. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Murray, A. T., trans. 1965. Homer. The Iliad. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1924.

- Murray, A. T., trans. 1966. Homer. Odyssey. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1919.

- Rackham, H., trans. 1952. Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Vol. 9. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Rackham, H., trans. 1968. Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Vol. 4. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library. Original edition, Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library, 1945.

- Shackleton Bailey, D. R., ed. and trans. 1993. Martial. Epigrams. Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA, London: Loeb Classical Library.

- Tomei, M. A. 2017. ‘Il monumento celebrativo della battaglia di Azio sul Palatino.’ MEFRA 129 (2). http://journals.openedition.org/mefra/4446.

- Vaticanus Lat. 3225 (Vergil, Opera).’ https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.lat.3225/0001.

- Walsh, P. G., trans. 1997. Cicero. The Nature of the Gods. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Waterfield, R., trans. 1998. Herodotus. The Histories. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

Secondary Sources

- Ambrosini, L. 2010. ‘Sui vasi plastici configurati a prua di nave (trireme) in ceramica argentata e a figure rosse.’ MEFRA 122 (1):73–115. https://doi.org/10.4000/mefra.336.

- Badoud, N. 2018. ‘La Victoire de Samothrace, défaite de Philippe V.’ RA 66 (2):279–306. https://doi.org/10.3917/arch.182.0279.

- Basch, L. 1985. ‘The Isis of Ptolemy II. Philadelphus. ‘ Mariner’s Mirror 2(71): 129–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00253359.1985.10656020.

- Basch, L. 1987. Le Musée imaginaire de la marine antique. Athènes: Institut Hellénique pour la Préservation de la Tradition Nautique.

- Berlinghieri, C. E. F. 2010. ‘Archimede alla corte di Hierone II: dall’idea al progetto della della più grande nave del mondo antico, la Syrakosia.’ Hesperia 26, Studi sulla grecità di Occidente: 169–88.

- Bourgeois, B. 2014. ‘(Re)peindre, dorer, cirer: la thérapéia en acte dans la sculpture grecque hellénistique.’ Technè 40: 69–80.

- Bubelis, W. 2010. ‘The sacred Triremes and their tamiai at Athens.’ Historia 59(4): 385–411.

- Carlson, D. 2009. ‘Seeing the Sea: Ships’ Eyes in Classical Greece.’ Hesperia 78: 347–65. https://doi.org/10.2972/hesp.78.3.347.

- Casson, L. 1964. ‘Odysseus’ boat (Od.V, 244–53).’ AJP 85:61–64.

- Casson, L.1992. ‘Odysseus’ boat (Od.V, 244–53).’, IJNA 21:73–74.

- Casson, L., and J. R. Steffy, eds. 1991. ‘The Athlit ram.’ College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Coarelli, F. 1999. La colonna Traiana. Rome: Istituto Archeologico Germanico Anno.

- Colombini, M. P., G. Giachi, F. Modugno, P. Pallecchi, and E. Ribechini. 2003. ‘Characterisation of paints and waterproofing materials of the shipwrecks found in the archaeological site of the Etruscan and Roman Harbour of Pisa (Italy).’ Archaeometry 45(4): 659–74. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1475-4754.2003.00135.x.

- Connan, J. 2002. ‘Le calfatage des bateaux.’ Pour la Science 298: 2–9.

- Connan, J., B. Maurin, L. Long and H. Sebire. 2002. ‘Identification de poix et de résine de conifère dans des échantillons archéologiques du lac de Sanguinet: exportation de poix en Atlantique à l’époque gallo-romaine.’ Revue d’Archéométrie 26: 177–96. https://doi.org/10.3406/arsci.2002.1032.

- Cousin, C. 1999. ‘Composition, espace et paysage dans les peintures de Polygnote à la leschè de Delphes.’ Gaia 4: 61–103.

- Croisille, J.-M. 2005. La Peinture romaine. Paris: Picard.

- De Ridder, A. 1915. ‘Protogène’ REG 128–129: 282–87.

- Daszewski, W. 1985. ‘Corpus of Mosaics from Egypt. Hellenistic and Early Roman Period.’ Aegyptiaca Treverensia 3 (1): 142–58.

- Fenet, A., and M. Jost. 2016. Les Dieux olympiens et la mer: espaces et pratiques cultuelles. Collection de l’École française de Rome 509. Rome: École française de Rome. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.efr.5580.

- Frost, H., ed. 1981. Lilybaeum (Marsala) The Punic Ship: Final excavation report. Atti della Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. Notizie degli scavi di antichità Suppl. of vol. 30 (1976). Rome: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei.

- Glasson, P. 2014. ‘Les représentations de la victoire navale de la haute époque hellénistique à Auguste.’ PhD. diss., Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV).

- Heipp-Tamer, C. 1993. Die Münzprägung der lykischen Stadt Phaselis in griechischer Zeit. Saarbrücker Studien zur Archäologie und Alten Geschichte 6. Saarbrücken: Saarbrücker Druckerei.

- Hölscher, T. 1973. Griechische Historienbilder des 5. Und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr.Beiträge zur Archäologie 6. Würzburg: Triltsch.

- Hölscher, T. 2015. La Vie des images grecques. Sociétés de statues, rôles des artistes et notions d’esthétiques dans l’art grec ancient. Paris: Hazan.

- Kyrieleis, H. 1980. ‘Archaische Holzfunde aus Samos.’ MDAI(A) 95: 89–94.

- Kyrieleis, H. 1993. ‘The Heraion at Samos.’ In Greek Sanctuaries. New Approaches, edited by N. Marinatos and R. Hägg, 99–122. New York: Routledge.

- La Torre, G. F., and M. Torelli. 2011. Pittura ellenistica in Italia e in Sicilia: linguaggi e tradizioni, Actes du colloque de Messine 24–25 septembre 2009, Archaeologica, 163, Rome: Giorgio Bretschneider Editore.

- Linant de Bellefonds, P., E. Prioux and A. Rouveret, eds. 2015. D’Alexandre à Auguste: dynamiques de la création dans les arts visuels et la poésie. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Linant de Bellefonds, P., and E. Prioux. 2017. Voir les mythes: poésie hellénistique et arts figures. Paris: Picard.

- Liou, B., and P. Pomey. 1985. ‘Recherches archéologiques sous-marines.’Informations archéologiques, Gallia 43 (2): 547–76.Mark, S. E. 1991. ‘Odyssey 5.234–53 and Homeric Ship Construction: A Reappraisal.’ AJA 95: 441–45.

- Mark, S. E. 1996. ‘Odyssey 5. 234–53 and Homeric ship construction: a clarification.’ IJNA 25:46–48.

- Mark, S. E. 2005. Homeric Seafaring. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

- Marlier, S. 2014. ‘L’épandage de poix.’ In Arles-Rhône 3. Un chaland gallo-romain du Ier siècle après Jésus-Christ, Archaeonautica 18, edited by S. Marlier, 115–16. https://doi.org/10.3406/nauti.2014.1316 Réunion des musées nationaux et du Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées. 2014. Auguste. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux—Grand Palais (exhibition catalogue 2013–2014).

- Nantet, E. 2016. ‘Phortia. Le tonnage des navires de commerce en Méditerranée du VIIIe siècle avant l’ère chrétienne au VIIe siècle de l’ère chrétienne.’ Rennes: Presses Universitaires.

- Plisecka, A. 2011. Tabula picta: Aspetti giuridici del lavoro pittorico in Roma antica. Padua: CEDAM.

- Pomey P., 2014. ‘Le projet Prôtis. Construction de la réplique navigante d’un bateau grec du VIe siècle av. J.-C.’ Comptes Rendus Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 3 (juillet–octobre): 1333–57.

- Pomey P., and P. Poveda. 2018. ‘Gyptis: Sailing Replica of a 6th-century-BC Archaic Greek Sewn Boat.’ International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 47(1): 45–56.

- Pomey P., and P. Poveda 2015. Le Gyptis, Reconstruction d’un navire antique. Notes photographiques Marseille (1993–2015). Paris: CNRS Éditions.

- Pomey, P., and A. Tchernia. 2006. ‘Les inventions entre l’anonymat et l’exploit: le pressoir à vis et la Syracusia.’ In Innovazione tecnica e progresso economico nel mondo romano, Atti degli incontri capresi di storia dell’economia antica (Capri: 2003), edited by E. Lo Cascio, 81–99. Bari, Edipuglia.

- Reinach, A. 1921. Textes grecs et latins relatifs à la peinture ancienne: recueil Milliet. Paris: Klincksieck. Reedited by A. Rouveret. 1985. Paris: Macula.

- Rieth, É., and A. Milon. 1981. Ex Voto marins dans le monde: de l’Antiquité à nos jours (catalogue d’exposition du Musée de la Marine). Paris: Musée National de la Marine.

- Rouveret, A. 1989. Histoire et imaginaire de la peinture ancienne (Ve siècle av. J.-C. – Ier siècle ap. J.-C.). (BEFAR 274). Rome: École française de Rome.

- Rouveret, A. 2017. ‘Adolphe Reinach (1887–1914): peinture antique et modernité.’ In Au-delà du savoir: les Reinach et le monde des arts. Cahiers de la villa Kérylos 28, edited by J. Jouanna, H. Lavagne and A. Pasquier, 61–84. Paris: Éditions de Boccard.

- Rutledge, S. H. 2012. Ancient Rome as a Museum. Power, Identity, and Culture of Collecting. Oxford Studies in Ancient Culture & Representation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199573233.001.0001.

- Snodgrass, A. 2001. ‘Pausanias and the Chest of Kypselos.’ In Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece, edited by S. E. Alcock, J. Cherry and J. Elsner, 127–41. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748623334.003.0023.

- Steffy, J.R. 1985. ‘The Herculaneum Boat: preliminary notes on hull details.’ AJA 89: 519–21.

- Tchernia, A. 1968–1970. ‘Premiers résultats des fouilles de juin 1968 sur l’épave 3 de Planier.’ Etudes Classiques, 3: 51–82.

- Tchernia, A. 2001.’Eustache et le rafiot d’Ulysse (Od.V).’ In Technai: techniques et sociétés en Méditerranée, edited by J.-P. Brun and P. Jockey, 625–31. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose.

- West, S. 2013. ‘Every Picture tells a Story.’ In Herodots Quellen. Die Quellen Herodots. Classica et Orientalia 6, edited by B. Dunsch, K. Ruffing and K. Dross-Krüpe, 117–28. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Wolfmayr, S. 2017. ‘Über die Bronzefunde der Nemisee-Schiffe.’ In Schiffe und ihr Kontext: Darstellungen, Modelle, Bestandteile: von der Bronzezeit bis zum Ende des Byzantinischen Reiches. Actes du colloque des 24–25 Mai 2013, edited by H. Frielinghaus, Th. Schmidts and V. Tsamakda, 91–104. Mayence: Schnell & Steiner.

Chapter 4 (55-74) from Sailing from Polis to Empire: Ships in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic Period, edited by Emmanuel Nantet (Open Book Publishers, 08.05.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.