The Bund’s defeat came not through civic enlightenment alone, but through federal prosecution and the geopolitical rupture of war.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Swastika Beneath the Stars and Stripes

In the quiet town of Yaphank, New York, nestled among the pines and suburban calm of Long Island, a startling tableau unfolded during the late 1930s. American children in brown shirts paraded with raised arms. Swastika flags flanked American ones along tidy dirt paths. And on summer weekends, visitors from across the region gathered not for barbecues or baseball, but for rallies extolling the virtues of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. This was not some abstract satire or misremembered dream. It was Camp Siegfried—a fully operational Nazi youth camp, planted not in Berlin or Munich, but in the heart of Roosevelt’s America.

The German American Bund, the organization behind this unsettling endeavor, cloaked its political allegiance in the language of heritage and patriotism. Formed from the ashes of earlier pro-German groups, the Bund was not simply an ethnic club or cultural society. It was a political movement, actively seeking to fuse American nationalism with German National Socialism. The story of Camp Siegfried and the Bund is not an aberration from American history but an uncomfortable part of it.

This essay examines the ideological origins, material structure, and cultural resonance of the German American Bund, with particular focus on Camp Siegfried as both a literal and symbolic space. By analyzing its rise, public appeal, and eventual fall, we confront a deeper question: how does fascism localize itself? And what happens when a foreign ideology is not imported but naturalized?

The Roots of the Bund: Between Heritage and Hate

From Friendship Societies to Fascist Cells

The German American Bund did not emerge from nowhere. It evolved from earlier pro-German organizations, most notably the Friends of New Germany, founded in 1933. The Friends were initially established with guidance from the Nazi Party in Germany and aimed to mobilize support among America’s sizable German immigrant population¹. However, when their overt foreign allegiance drew public suspicion and federal scrutiny, the group rebranded itself in 1936 as the German American Bund, under the leadership of Fritz Kuhn, a German-born naturalized citizen and fervent Hitler admirer².

The Bund presented itself as both an ethnic fraternity and a patriotic American organization. Its members argued that they were simply preserving German heritage while defending the United States against the twin evils of communism and Jewish “infiltration.” The ideological slippage between cultural pride and political extremism was not accidental. It was strategic.

Kuhn styled himself as an “American Führer,” and his speeches were carefully crafted to echo Hitler’s rhetoric while appealing to American grievances. Among these were economic despair, cultural anxiety, and political fatigue following the Great Depression. The Bund organized rallies, published propaganda, and opened youth camps not only to recruit but to root itself within American soil. Their slogan, “America for Americans,” masked its ethnic exclusivity behind a veil of nationalist populism³.

The Appeal of American Fascism

The Bund’s appeal rested not only on ideology but on aesthetics and structure. Its members wore uniforms, adopted military ranks, and held mass rallies in urban centers and rural retreats alike. The performative power of fascism – its pageantry, discipline, and mythic vision of order – found fertile ground among Americans who saw the New Deal as insufficient or untrustworthy.

The group’s emphasis on anti-communism also provided cover for broader bigotry. By denouncing the Soviet Union, the Bund cast itself as a defender of capitalism and national sovereignty. Its antisemitism, though virulent and central, was often couched in economic language. Jews were portrayed not merely as racial outsiders but as financial manipulators and communist conspirators⁴. This dual rhetoric allowed the Bund to circulate in conservative and even centrist circles without immediate rejection.

Still, its ideology remained firmly tethered to Hitler’s vision. The Bund celebrated Hitler’s birthday, displayed portraits of him at meetings, and maintained correspondence with German officials. While claiming to be American patriots, they revered a foreign dictator whose regime openly opposed the democratic order.

Camp Siegfried: Architecture of a Domestic Reich

Designing a Nazi Geography

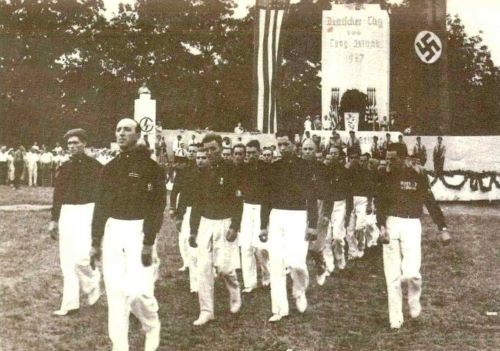

Camp Siegfried, established in 1935 by the Bund in Yaphank, was not simply a summer camp. It was a miniature version of the Third Reich. Streets were renamed after Nazi officials—Goebbels Street, Hitler Street, and others. Uniformed children drilled in formation. Swastika-shaped flower beds adorned public spaces. Every element of the camp’s design was pedagogical. Its geography taught ideology⁵.

The camp hosted weekend gatherings, youth training, theatrical performances, and “patriotic” parades, all tailored to infuse National Socialist values into American soil. Families would travel by train from New York City, greeted by banners that bore both swastikas and American flags. The visual synthesis was deliberate, meant to assert that fascism and Americanism were not opposites, but complements.

Perhaps most unsettling was the normalization of these symbols. Camp Siegfried functioned in broad daylight. Photos of girls in dirndls and boys in khaki shorts fill archival records, suggesting a bizarre pastoral innocence that thinly veiled a program of indoctrination. It was, quite literally, fascism with a family face.

Community, Exclusion, and the Politics of Belonging

The camp’s effectiveness was rooted in its sense of community. Members felt affirmed, part of a cause that promised order, clarity, and a return to strength. It provided identity in a time of confusion and decline. But this identity was built upon exclusion. Jews were barred from entering. Catholic Germans were often marginalized. The Aryan ideal, exported from Munich and recast in Long Island pines, was rigidly enforced.

The Bund also used the camp to cultivate political clout. Its leaders hosted public officials, businessmen, and journalists, offering them tours and speaking engagements that softened the Bund’s image while subtly spreading its ideology. In this sense, Camp Siegfried functioned as both a physical retreat and a political engine.

What makes Camp Siegfried particularly alarming in retrospect is not its secretiveness, but its openness. It reveals how fascism need not hide. It can wrap itself in local flags, speak the local language, and invoke the local traditions, all while sowing the seeds of authoritarianism.

Surveillance, Resistance, and Collapse

The Federal Response and Kuhn’s Downfall

By 1939, the rise of the Bund had begun to alarm federal authorities. The FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, opened investigations into the group’s finances and foreign affiliations. Public outcry also intensified after the Bund’s infamous Madison Square Garden rally in February 1939, where Kuhn spoke to a crowd of over twenty thousand beneath a massive portrait of George Washington flanked by swastikas⁶.

The rally backfired. It brought national attention and widespread condemnation. Journalists, civil rights groups, and politicians began demanding action. In 1939, Kuhn was arrested for embezzlement, having stolen funds from the Bund to support his personal affairs. Though the charges were financial rather than ideological, the conviction was symbolic. The Führer of American fascism had fallen⁷.

The Bund quickly lost momentum. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, the government formally dissolved the organization. Camp Siegfried was shuttered, its grounds later sold and incorporated into a residential community. The streets still bore Nazi names into the 1950s.

Memory, Myth, and the Long Echo

Though the Bund dissolved, its legacy lingered. The idea that fascism could take root in American soil was not erased but suppressed. Camp Siegfried faded into local memory as an oddity or embarrassment, rarely taught in schools or discussed in public. Yet the social dynamics that made it possible (economic dislocation, cultural fear, scapegoating, and the appeal of order) have not vanished.

The camp stands as a warning. Fascism does not always arrive with tanks and banners. Sometimes it enters through the backyards of those who believe they are defending tradition. It offers identity, structure, and myth in exchange for truth, tolerance, and democracy.

Conclusion: The Fragile Boundaries of the Homeland

The German American Bund and Camp Siegfried challenge our assumptions about where fascism belongs. They demonstrate that the ideology of exclusion and domination is not foreign to American soil. It has lived here, spoken in American accents, dressed in American flags, and taught children to salute a foreign tyrant as a moral hero.

The Bund’s defeat came not through civic enlightenment alone, but through federal prosecution and the geopolitical rupture of war. Yet the structures it exploited (nostalgia, ethnic anxiety, disillusionment) remain susceptible to new iterations.

History does not repeat, but it echoes. And in the echoes of Camp Siegfried, we hear a question as urgent now as then: what must we guard, and whom must we remember, to keep the landscape of democracy from being planted with flags of hate?

Appendix

Footnotes

- Bradley W. Hart, Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2018), 34–36.

- Sander A. Diamond, The Nazi Movement in the United States, 1924–1941 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974), 83.

- Arnie Bernstein, Swastika Nation: Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014), 101–104.

- Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975.

- Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, “Nazis on Long Island: The Story of Camp Siegfried,” Museum of Jewish Heritage, accessed July 29, 2025, https://mjhnyc.org/blog/nazis-on-long-island-the-story-of-camp-siegfried/.

- Hart, Hitler’s American Friends, 212–217.

- Bernstein, Swastika Nation, 251–253.

Bibliography

- Bernstein, Arnie. Swastika Nation: Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014.

- Diamond, Sander A. The Nazi Movement in the United States, 1924–1941. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974.

- Hart, Bradley W. Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2018.

- Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. “Nazis on Long Island: The Story of Camp Siegfried.” Museum of Jewish Heritage, January 21, 2022. https://mjhnyc.org/blog/nazis-on-long-island-the-story-of-camp-siegfried/

- Sontag, Susan. “Fascinating Fascism.” The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.