Six amendments have been submitted to the states but were never ratified.

By Jessie Kratz

Historian

United States National Archives

Introduction

To date, the U.S. Constitution has 27 amendments. The first 10 are known as the Bill of Rights, then the rest generally protect and expand individual rights or outline how government works. Congress, however, has actually proposed 33 constitutional amendments to the states.

Over the next couple of months we’ll be looking at the amendments that Congress proposed but were not ratified by a sufficient number of states (three-fourths of the states must pass an amendment for it to become law). The unratified amendments deal with representation in Congress, titles of nobility, slavery, child labor, equal rights, and DC voting rights.

Today we’re taking a closer look at the earliest unratified amendment. In fact, it was the very first amendment ever proposed. Back in 1789, the first Congress drafted 12 amendments and sent them to the states for ratification. By December 15, 1791, enough states had ratified 3 through 12, which eventually became known as the Bill of Rights. Over 200 years later, the original second proposed amendment became the 27th Amendment in 1992.

But what happened to the first?

The original first (proposed) amendment outlined how many representatives would be in the U.S. House of Representatives. It read:

After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.

Had that passed, we could have more than 6,000 representatives today compared to the 435 we currently have.

The proposed amendment actually came within just one state of being ratified. But by December 15, 1791, when Virginia ratified amendments 2 through 12, it was still short, and action on it ceased. Since Congress did not put a ratification deadline on the proposed amendment, it could theoretically still be ratified. Since only 11 states have ratified it, however, it would need an additional 27 states to be adopted.

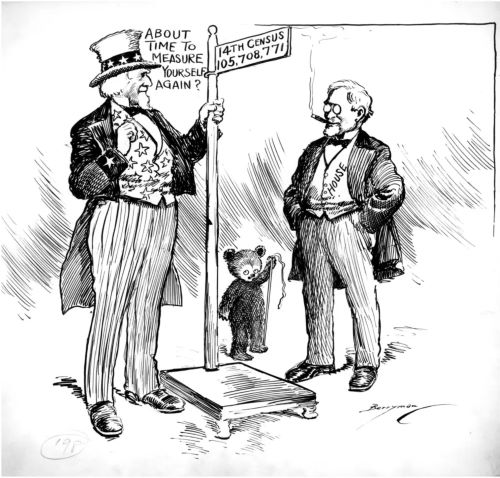

Since the amendment failed, Congress has been determining the size of the House of Representatives as they saw fit. In 1911, recognizing that the House of Representatives was expanding to unmanageable proportions, Congress decided to limit the number of members to 433. The number was fixed at 433 because it was the lowest number that would prevent any state from losing a member (as you can imagine, no state wanted to lose representation in Congress).

Congress also allowed for the addition of one representative for each of the soon-to-be states of Arizona and New Mexico, which brought the total to 435. Exactly how those 435 seats would be divided among the states has been debated and altered, but the number remains at 435. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 reaffirmed the number.

The only time the number of representatives in the House changes is when a new state is admitted. When this happens, each new state gets one representative until the next census. This is what occurred when Hawaii and Alaska were admitted in 1959—the size of the House temporarily increased to 437 until the 1960 census.

So, unless the requisite states decide to pass the amendment, the House of Representatives will continue to be set at 435.

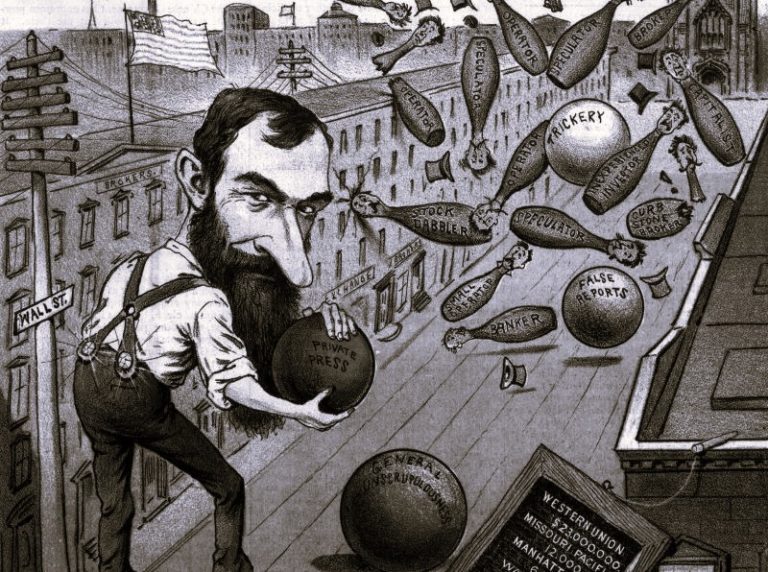

Titles of Nobility

The U.S. Constitution has a Titles of Nobility clause that prohibits the Federal Government from granting titles of nobility and restricts government officials from receiving gifts, emoluments, offices, or titles from foreign states without Congress’s consent.

Also known as the “Emoluments Clause,” it was written to prevent Federal officeholders from being corrupted by foreign entities. However, it does not prevent all U.S. citizens from accepting titles of nobility from royalty and opens the door for such action with Congress’s consent.

During the Constitution’s ratification, several states proposed amendments that would either forbid Congress from granting consent or would have eliminated the “without the consent of Congress” clause. While the first Congress discussed the issue, it was not among the proposed amendments that eventually became the Bill of Rights.

In the lead-up to the War of 1812 with Great Britain, there was some anxiety about European influence on the United States’ nascent republic. In 1810, Senator Philip Reed of Maryland introduced a constitutional amendment modifying the Titles of Nobility Clause.

In order for an amendment to pass Congress, both houses must approve it by two-thirds majority. On April 27, 1810, the Senate approved the amendment by a vote of 19–5, and on May 1, 1810, the House of Representatives approved it by a vote of 87–3—both well above the necessary super majority.

The final text of the amendment read:

If any citizen of the United States shall accept, claim, receive or retain, any title of nobility or honour, or shall, without the consent of Congress, accept and retain any present, pension, office or emolument of any kind whatever, from any emperor, king, prince or foreign power, such person shall cease to be a citizen of the United States, and shall be incapable of holding any office of trust or profit under them, or either of them.

The amendment was then sent to the state legislatures for ratification but never reached the three-fourths threshold to be added to the Constitution. Had enough states ratified it, it would have become the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Because the amendment was passed before Congress began the practice of setting a time limit for ratification, the amendment technically can still be ratified if 38 states in total adopted it.

Even though an insufficient number of states ratified the amendment, there was confusion over its status throughout the 19th century, and it appeared in a limited number of printed versions of the Statutes at Large, printed copies of the Constitution, and other publications.

Because the Archivist of the United States has statutory responsibility to certify constitutional amendments, the National Archives looked into the issue in 1994. The Archives concluded it only has authority to determine whether sufficient notices of ratification have been received from three-fourths of the current number of states. Since the country has 50 states, 38 state ratifications would be needed for the amendment to become law.

Protection of Slavery

When the second session of the 36th Congress convened in late 1860, the issue of slavery had grown increasingly divisive, and Congress was struggling to find ways to preserve the Union. Both the House and the Senate formed committees to tackle the slavery issue and attempt to quell the looming secession crisis.

On January 14, 1861, the House committee submitted, among other measures, a constitutional amendment to protect slavery. This was an attempt to appease the Southern states, and while the amendment had some support, the required two-thirds of the House was not on board.

On February 26, 1861, Representative Thomas Corwin of Ohio introduced his own text for an amendment protecting slavery. It read:

No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any state, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.

Two days later, the House approved Corwin’s proposed amendment by a vote of 133–65, just above the two-thirds threshold. The Senate took up the proposed amendment on March 2, 1861, passing it with exactly the two-thirds super majority needed: 24–12.

Just before leaving office, President James Buchanan signed the amendment, unnecessarily, since the President has no constitutional role in approving amendments. Buchanan’s successor, Abraham Lincoln, who took office on March 4, sent the proposed amendment to the states for ratification.

Had enough states ratified the amendment, it would have been the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. However, the amendment failed to stop Southern secession, and by that summer, 11 Southern states had seceded from the Union. For the next four years the U.S was embroiled in civil war.

In the final months of the war, Congress passed another slavery-related amendment, but this one had the opposite intention. It read:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

On December 6, 1865, Georgia became the 27th state to ratify the amendment, which pushed it over the three-fourths mark. On December 18, 1865, Secretary of State William Seward certified it, stating that the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery had been adopted as part of the U.S. Constitution effective December 6, 1865.

Regulating Child Labor

During the Progressive Era, muckraking journalists and photographers drew public attention to a myriad of America’s social problems, one of them being the exploitation of children. Perhaps most famous was Lewis Hine, who was a photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. Hine’s photographs documented the working conditions of children in factories, fields, and mines.

In 1916, in an attempt to regulate child labor, Congress passed the Keating-Owen Child Labor Act. The act banned the sale of products from any factory, shop, or cannery that employed children under the age of 14, from any mine that employed children under the age of 16, and from any facility that had children under the age of 16 working at night or for more than 8 hours during the day. Congress cited its authority to pass the law stemmed from the Federal Government’s ability to regulate interstate commerce.

In 1918, however, the United States Supreme Court ruled the act was unconstitutional because it overstepped the purpose of the government’s powers to regulate interstate commerce. Congress passed another child labor bill in 1918, this time citing the Federal Government’s power to levy taxes. In 1922 the Supreme Court found it unconstitutional as well.

Congress next tried to regulate child labor through a constitutional amendment. It read:

Section 1. The Congress shall have power to limit, regulate, and prohibit the labor of persons under eighteen years of age.

Section 2. The power of the several States is unimpaired by this article except that the operation of State laws shall be suspended to the extent necessary to give effect to legislation enacted by the Congress.

The House of Representatives passed the joint resolution on April 26, 1924, by a vote of 297–69; and Senate the passed it on June 2, 1924, by a vote of 61–23. The proposed constitutional amendment was then submitted to the state legislatures for ratification.

After a few state ratifications in 1924 and 1925, the amendment stalled, mostly because of a successful ad campaign to discredit it. By 1937, when the most recent state passed the amendment, only 28 states had ratified it. This fell short of the required three-fourths threshold. The amendment is still outstanding, however, and ratification by 10 more states (38 states in total) is required to add the amendment to the Constitution.

Congress obtained Federal protection for children in 1938, when it passed the Fair Labor Standards Act. The act prohibits “oppressive child labor” in the United States, which is defined, with exceptions, as the employment of youth under the age of 16 in any occupation or the employment of youth under 18 years old in hazardous occupations. The act was also challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court, but this time the act was upheld.

The Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed constitutional amendment that would guarantee equal rights under the law regardless of sex. It was first drafted in 1923 by suffragist Alice Paul, and since then some version of the ERA was introduced in every session of Congress until 1971.

In 1971, Representative Martha Griffiths introduced H.J. Res. 208, proposing an Equal Rights Amendment. The text read:

Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

While previous attempts to pass the ERA rarely got out of committee, H.J. Res. 208 not only made it to the floor, it was successful. On October 12, 1971, the House approved Griffiths’s version of the ERA by a vote of 354–24. The Senate approved an identical version on March 22, 1972, by a vote of 84–8.

Congress then sent the ERA to the states but included a seven-year deadline for ratification. In 1978, with the seven-year deadline approaching, the ERA was three states short of reaching the required three-fourths mark. Congress decided to extend the time limit to June 30, 1982; however, no additional states ratified the amendment during its extension.

Controversy surrounding the Equal Rights Amendment persists today. Despite failing to garner enough states by the deadline, three additional states have ratified the amendment in recent year’s putting the status of the amendment into question.

The Archivist of the United States has statutory responsibilities regarding certifications of constitutional amendments. Because of the ongoing uncertainty surrounding the ERA, the National Archives requested guidance from the Department of Justice on the legal issues regarding ratification of the amendment.

In January 2020, the Department of Justice issued its opinion, concluding “that Congress had the constitutional authority to impose a deadline on the ratification of the ERA and, because that deadline has expired, the ERA Resolution is no longer pending before the States.”

The National Archives issued a press release on the current status of the ERA, saying the Archivist will abide by the Justice Department’s opinion unless otherwise directed by a final court order.

DC Voting Rights

For most of its history, the residents of Washington, DC, have lacked representation in Congress and the ability to participate in elections for President. The situation was partially rectified in 1961 with the 23rd Amendment, which gave the District’s residents the right to participate in the Electoral College. However, the allocation of votes was not based on DC’s population but was instead limited to the same number of electoral votes as the least populous state. The amendment also did not address the issues of DC home rule, nor did it extend representation in Congress.

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson changed the District government’s form to a mayor and city council appointed by the President. Three years later, Congress gave DC a nonvoting Delegate to the House of Representatives. Congress made further steps to address the disenfranchisement of DC residents in 1973 with the District of Columbia Home Rule Act, which established an elected mayor and an elected 13-member council for the District, although Congress retained ultimate authority over DC’s laws.

At the Federal level, in 1977 Representative Don Edwards of California, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights, introduced H.J. Res. 554 proposing the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment.

The amendment would have given the District of Columbia full representation in Congress, full representation in the Electoral College, and full participation in the constitutional amending process.

The House Judiciary Committee incorporated a seven-year ratification deadline directly in the body of the resolution rather than in the preamble so Congress could not extend the deadline for ratification by a simple majority vote. The full proposed amendment read:

Section 1. For purposes of representation in the Congress, election of the President and Vice President, and article V of this Constitution, the District constituting the seat of government of the United States shall be treated as though it were a State.

Section 2. The exercise of the rights and powers conferred under this article shall be by the people of the District constituting the seat of government, and as shall be provided by the Congress.

Section 3. The twenty-third article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

Section 4. This article shall be inoperative, unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission.

The House passed the proposed amendment on March 2, 1978, by a vote of 289 to 127, 11 votes more than the two-thirds constitutional requirement. The Senate passed the proposed amendment on August 22 by a vote of 67 to 32, one vote more than the requirement. The amendment then went to the states for ratification, but when the seven years came to an end in 1985, only 16 states had approved the amendment, 22 states short of the three-fourths needed.

Because the amendment failed, citizens of the District continue to lack representation in Congress, the ability to participate in the constitutional amending process, and full rights in the Electoral College. Beginning in 2000, the District’s license plate began to feature the slogan “Taxation Without Representation,” referring to that fact the District’s residents must pay Federal income tax but lack full voting rights.

Originally published by Pieces of History, United States National Archives and Records Administration, 01.23.2020, to the public domain.