Noncooperation in India demonstrated that power is most vulnerable not when it is attacked, but when it is quietly abandoned.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power without Participation

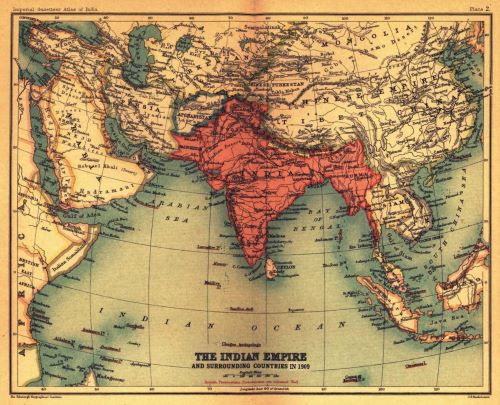

British imperial rule in India rested on an appearance of overwhelming strength and permanence. The Raj commanded armies, controlled railways, levied taxes, and governed through an elaborate administrative apparatus that extended across the subcontinent. Its symbols were visible everywhere, from courtrooms and cantonments to schools and postal routes, reinforcing the sense that British authority was inescapable. Yet this dominance concealed a structural fragility that was rarely acknowledged in official rhetoric. British authority depended not only on coercive capacity but on the daily cooperation of millions of Indians who staffed offices, attended government schools, served in colonial courts, purchased imported goods, and treated imperial institutions as legitimate. Power, though coercive in potential, was participatory in function. Without routine compliance and consent, the empire could govern only at enormous cost and with diminishing effectiveness.

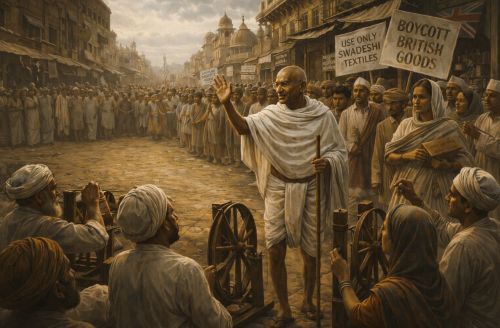

Mahatma Gandhi’s political insight lay in recognizing this dependency and treating it as a strategic opening rather than a constraint. Rather than confronting British rule through armed revolt, insurrection, or dramatic symbolic defiance, he identified participation itself as the empire’s most critical vulnerability. Violence, he argued, played to imperial strengths by legitimizing repression and unifying authority against a visible threat. Withdrawal, by contrast, exposed the relational nature of power by denying the empire the cooperation it required to function smoothly. If Indians refused to participate in British systems of administration, commerce, education, and legal authority, the empire would remain armed and intact, but increasingly hollow. Noncooperation was not an expression of weakness or passivity. It was a calculated refusal to sustain the structures that transformed domination into routine governance.

The Swadeshi movement emerged from this logic of refusal. By boycotting British goods and institutions while promoting indigenous practices, Gandhi reframed resistance as disengagement rather than attack. The emphasis was not on destroying imperial symbols but on eroding their relevance. Courts could exist without litigants. Schools could operate without students. Markets could function without buyers. Each act of withdrawal reduced the empire’s ability to normalize itself as the natural framework of Indian life. Noncooperation operated quietly, targeting systems rather than spectacles and legitimacy rather than sovereignty.

What follows argues that noncooperation succeeded because it addressed the conditions under which power functioned rather than its outward manifestations. British rule in India did not collapse under military pressure, nor was it defeated through a single decisive confrontation. Instead, it weakened as participation declined and legitimacy eroded. Swadeshi and related campaigns demonstrated that authority could endure violence but not indifference. When people opted out together, power did not fall suddenly. It bled steadily, revealing that domination without participation is unsustainable in the long term.

The Architecture of British Rule in India

British rule in India was sustained through a layered administrative architecture that relied heavily on Indian participation at every level. While ultimate authority rested with colonial officials, the day-to-day functioning of the Raj depended on Indian clerks, revenue collectors, police, teachers, and legal intermediaries. This system allowed a relatively small number of British administrators to govern a vast and diverse population. The empire’s reach appeared expansive, but its depth was shallow. Authority flowed through Indian hands, making cooperation not incidental but essential to imperial governance.

Revenue collection formed the financial backbone of this architecture and revealed its dependence on routine compliance. Land taxes, customs duties, and excise levies were assessed and gathered largely by Indian officials operating within colonial frameworks, often drawing on precolonial practices adapted to imperial needs. These revenues funded administration, infrastructure projects such as railways and canals, and the maintenance of military forces that symbolized British dominance. Yet this fiscal system depended on predictability rather than constant coercion. Villages paid assessments, merchants remitted duties, and landlords enforced collections as part of established cycles of obligation. Compliance was normalized through bureaucratic routine, not enforced daily at gunpoint. British power rested on the steady reproduction of economic participation rather than on perpetual violence.

The legal system further illustrates this dependence and its inherent vulnerability. British courts required litigants, lawyers, clerks, and local enforcement mechanisms to function at all. While imperial law asserted ultimate authority, its legitimacy depended on recognition and use by the population it governed. Indians who brought disputes before colonial courts implicitly acknowledged British jurisdiction as a valid forum for justice. This participation normalized imperial law as part of social life. Yet the system remained precarious. Courts without litigants, lawyers without clients, and judgments without voluntary compliance exposed the limits of legal authority. Withdrawal from legal participation threatened not merely administrative efficiency but the symbolic legitimacy of colonial rule itself.

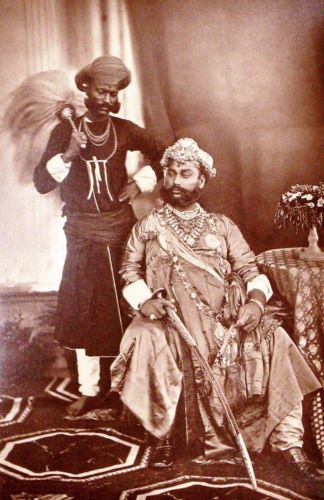

Education and professional advancement further bound Indians to imperial systems while deepening structural dependence. British-run schools and universities trained an Indian elite in English language, legal reasoning, and administrative norms, preparing them for roles in colonial bureaucracy, law, and commerce. These institutions offered pathways to status, employment, and social mobility, aligning individual ambition with imperial structures. Participation came at the cost of cultural accommodation, but refusal carried its own penalties in opportunity and security. Yet this reliance created a long-term vulnerability. If students rejected colonial education or professionals refused imperial credentials, the empire’s ability to reproduce its administrative class would erode gradually but decisively. The very mechanisms that stabilized rule also exposed it to disciplined withdrawal.

The architecture of British rule functioned as a system of managed cooperation. Coercion remained available and was periodically deployed, but it was neither sufficient nor efficient as a governing principle across such a vast population. The Raj depended on Indians to operate its machinery, normalize its presence, and translate authority into everyday practice. This dependence made the empire resilient in appearance but fragile in substance. Once participation became contestable, the entire structure stood exposed. Noncooperation did not need to dismantle institutions by force. It only needed to deprive them of the cooperation that made them work.

Swadeshi and the Logic of Economic Refusal

Swadeshi emerged as a practical expression of noncooperation grounded in everyday economic behavior. Rather than calling for dramatic confrontation with British authority, Gandhi emphasized withdrawal from imperial markets as a means of resistance accessible to ordinary people. The boycott of British goods, especially textiles, became the most visible element of this strategy. Cloth was not only a major British export to India but a daily necessity for millions. By refusing imported fabric, Indians challenged a central artery of imperial commerce without attacking symbols of power directly.

The logic of economic refusal rested on a clear diagnosis of imperial dependence that went beyond moral condemnation. British rule relied on India simultaneously as a captive market and a revenue-generating colony. Imported goods produced profits for British manufacturers and merchants, while customs duties reinforced the colonial fiscal structure. Swadeshi targeted this relationship by disrupting demand rather than attempting to sabotage production. British factories could continue operating, ships could continue arriving at Indian ports, and warehouses could remain stocked. What could not be compelled was purchase. By refusing to buy, Indians exposed the limits of imperial power in the economic realm, revealing that even a coercive system depended on voluntary consumer behavior. Economic refusal transformed passive participation into active leverage.

Gandhi framed Swadeshi not as mere boycott but as moral discipline. Spinning and wearing khadi symbolized self-restraint, patience, and collective responsibility. The act of producing one’s own cloth was intentionally slow and laborious, contrasting with the speed and scale of industrial production. This was not an accident. Gandhi understood that discipline was central to noncooperation. Swadeshi trained participants to accept inconvenience as a political act, reinforcing the idea that resistance required sustained commitment rather than episodic protest.

Importantly, Swadeshi did not depend on immediate economic substitution to be effective, a point often misunderstood by critics. Debates over whether indigenous production could fully replace British imports obscured the strategic purpose of the movement. The power of refusal lay not in perfect self-sufficiency but in disruption and delegitimation. Even partial withdrawal unsettled markets, reduced profits, and introduced uncertainty into imperial planning. British officials worried less about the success of Indian industry than about the unpredictability of demand. By prioritizing refusal over replacement, Swadeshi ensured that participation did not hinge on economic efficiency. Moral resolve, not productivity, sustained the movement.

Swadeshi also functioned as a unifying practice across social, regional, and economic divisions. While inequality shaped the form participation took, the principle of refusal remained broadly accessible. Wealthier Indians could renounce imported luxuries and public markers of colonial status, while poorer participants rejected cheap British cloth despite the personal cost. Spinning, wearing khadi, and avoiding foreign goods became shared acts that cut across caste and class distinctions. This inclusivity strengthened noncooperation by making it visible everywhere, not confined to elites or activists. Swadeshi operated as a national discipline, reinforcing solidarity through repeated, ordinary acts of withdrawal.

Through Swadeshi, economic refusal became a language of political expression. Each rejected purchase communicated dissent without requiring confrontation or spectacle. Markets became arenas of quiet resistance, where everyday decisions accumulated into systemic pressure. The British response underscored the effectiveness of this approach. Officials worried less about slogans or marches than about declining demand and eroding revenues. Swadeshi demonstrated that noncooperation could weaken imperial power by denying it the participation it required, proving that refusal, when organized collectively and sustained, could operate as a disciplined and relentless force.

Noncooperation beyond the Marketplace

Gandhi’s strategy extended far beyond economic boycott, expanding noncooperation into a comprehensive refusal of imperial institutions that structured everyday life under British rule. While Swadeshi targeted markets, noncooperation addressed the broader architecture of authority by withdrawing participation from courts, schools, administrative offices, and symbolic honors. The aim was not to overthrow these institutions through force or public spectacle, but to render them ineffective by depriving them of legitimacy and users. British power, though formidable in coercive capacity, relied on Indians to staff offices, attend schools, file cases, and treat imperial systems as normal and authoritative. Withdrawal exposed how hollow that authority became when participation was no longer taken for granted.

One of the most consequential forms of noncooperation was the boycott of British courts. Gandhi urged Indians to settle disputes through local arbitration rather than imperial legal systems. Colonial courts depended on litigants to function, and their authority rested on public recognition of British law as legitimate. When Indians refused to bring cases, the courts did not merely lose efficiency. They lost relevance. This refusal challenged the symbolic core of imperial sovereignty, revealing that legal authority cannot operate in isolation from social acceptance.

Education was another critical site of disengagement. British schools and universities trained Indians to serve within colonial administration and commerce, reproducing the imperial system across generations. Gandhi called for withdrawal from these institutions and the creation of national schools that emphasized indigenous values and self-rule. This was a long-term strategy aimed at disrupting the reproduction of colonial dependency rather than producing immediate political concessions. Refusing colonial education carried personal cost, but it undermined the empire’s capacity to cultivate loyal intermediaries essential to governance.

Noncooperation also extended to employment and honors within the colonial system, striking directly at the moral prestige of imperial rule. Indians were encouraged to resign from government posts, refuse titles, and reject advisory roles that symbolized collaboration. These positions did not merely administer policy. They lent credibility to British authority by suggesting consent and partnership. When respected figures withdrew, the appearance of representative governance fractured. Collaboration ceased to appear neutral or pragmatic and instead became morally suspect. Authority that once seemed inclusive began to look isolated, dependent on coercion rather than shared purpose.

These forms of noncooperation transformed refusal into a comprehensive political strategy that operated across social, legal, and institutional domains simultaneously. Withdrawal compounded its effects by denying the empire legitimacy at multiple points of contact. The British could suppress demonstrations, censor newspapers, or jail leaders, but they could not easily compel Indians to attend schools, staff offices, or voluntarily legitimize courts. Noncooperation beyond the marketplace revealed a structural truth about empire. Governance depended on participation far more than it admitted. By opting out collectively, Indians did not confront power directly. They drained it of the cooperation that sustained it, exposing the limits of coercion in the absence of consent.

Legitimacy, Obedience, and the Limits of Repression

British responses to noncooperation relied heavily on repression, revealing the limits of coercion as a substitute for legitimacy. Arrests, censorship, bans on organizations, and the use of emergency powers were deployed repeatedly to disrupt Gandhi’s campaigns and restore compliance. Leaders were imprisoned, publications suppressed, meetings prohibited, and entire regions placed under extraordinary policing. These measures projected strength, but they addressed symptoms rather than causes. Repression could silence individuals and disperse crowds, yet it could not recreate the conditions of consent that noncooperation intentionally withdrew. Each new restriction underscored the state’s dependence on force, exposing a widening gap between the capacity to punish and the capacity to govern through accepted authority.

Obedience under imperial rule had always rested on more than fear. The Raj functioned because colonial authority was routinized, normalized, and woven into everyday life. Taxes were paid, courts were used, schools were attended, and offices were staffed because these practices appeared stable and unavoidable. Noncooperation disrupted this normalization. When Indians refused to comply voluntarily, the state was forced to rely more visibly on coercion, undermining its own claims to legitimacy. Each act of repression made the empire appear less like a governing authority and more like an occupying force, eroding the moral foundations of obedience.

The imprisonment of Gandhi and other leaders illustrates this dynamic with particular clarity. British officials assumed that removing charismatic figures would collapse the movement by depriving it of direction and cohesion. Instead, arrests often intensified participation by confirming the moral contrast between disciplined refusal and coercive rule. Gandhi’s willingness to accept imprisonment reinforced the ethical logic of noncooperation, transforming repression into evidence of imperial insecurity. Crucially, the movement had been structured to survive decapitation. It relied on dispersed participation rather than centralized command, on habits of refusal rather than constant leadership. This asymmetry favored noncooperation. The empire could arrest leaders, but it could not arrest millions of individual decisions to withdraw.

Repression also carried mounting administrative and political costs that compounded its ineffectiveness. Sustained coercion required expanded surveillance, increased policing, and significant financial expenditure, straining colonial resources already under pressure. It also generated international scrutiny, inviting criticism from British liberals and global observers who questioned the moral legitimacy of imperial rule. Official reports, commissions, and parliamentary debates revealed growing anxiety that repression was not restoring stability but deepening alienation. Each new emergency measure conceded that obedience could no longer be assumed. Authority was being enforced, but governance was deteriorating, and the distinction between the two became increasingly difficult to conceal.

The limits of repression became most visible in what it failed to achieve. Despite arrests, bans, and violence, noncooperation persisted in altered forms. Participation did not return to previous levels, and legitimacy did not recover. The British could compel compliance in isolated instances, but they could not recreate the conditions of voluntary obedience that sustained rule over time. Noncooperation demonstrated a fundamental imbalance. Power could punish refusal, but it could not compel belief, loyalty, or participation indefinitely. Where legitimacy eroded, repression filled the gap, and in doing so, revealed its own inadequacy.

Mass Participation and the Discipline of Refusal

Noncooperation succeeded only because it moved beyond elite leadership and became a mass practice sustained by discipline. Gandhi understood that withdrawal without coordination would collapse into fragmentation or be neutralized through selective repression. The power of refusal lay not in isolated acts, but in synchronized behavior repeated across regions, classes, and communities. Millions participated not by marching or fighting, but by altering routines. Spinning cloth, refusing schools, boycotting goods, and declining cooperation became ordinary acts performed at scale. Mass participation transformed noncooperation from protest into a social condition that the empire had to manage rather than suppress episodically.

Discipline was central to this process, and Gandhi treated it as a political requirement rather than a purely moral virtue. He insisted that noncooperation demanded restraint, patience, and self-control, rejecting spontaneous violence, retaliation, or symbolic aggression even when repression intensified. This insistence was strategic. Violence fractured coalitions by privileging those willing to take risks others could not, while simultaneously providing the colonial state with justification for sweeping repression. Discipline preserved unity by keeping the movement accessible to participants across caste, class, and region, many of whom could not afford the consequences of open confrontation. By maintaining nonviolence and procedural refusal, the movement denied the empire a clear security pretext and forced it to confront withdrawal as a problem of legitimacy rather than public order.

Mass participation also depended on repetition rather than intensity, a feature that distinguished noncooperation from insurrectionary movements. Noncooperation did not rise and fall like a revolt. It persisted through daily practices that required little centralized coordination once norms were established. This persistence frustrated colonial authorities accustomed to responding to discrete events such as strikes, riots, or demonstrations. There was no single moment to defeat, no battlefield to clear, and no leader whose removal could terminate participation. Discipline turned time itself into leverage. Each day of continued refusal compounded administrative strain, disrupted routines of governance, and normalized disengagement. Returning to previous patterns of obedience became socially and psychologically costly, even when repression temporarily intensified.

The discipline of refusal also produced internal coherence. By emphasizing moral restraint and collective responsibility, Gandhi framed participation as a shared ethical commitment rather than a tactical calculation. This framing reduced defection by embedding noncooperation within identity and community expectation. To participate was not merely to oppose British rule, but to enact a vision of self-rule through behavior. Mass participation sustained by discipline demonstrated that power could be contested without confrontation. When refusal became habitual and widespread, it restructured the relationship between ruler and ruled, revealing that authority dependent on cooperation could be undermined quietly and persistently.

Economic Consequences and Imperial Anxiety

Noncooperation generated economic consequences that accumulated gradually rather than erupting suddenly, and it was this slow, persistent pressure that unsettled imperial authorities most deeply. Boycotts of British goods reduced demand in key sectors, especially textiles, which had long relied on India as a captive market within the imperial economy. Even when declines were uneven, regional, or partial, they introduced uncertainty into commercial planning and revenue expectations. Merchants, manufacturers, and colonial officials could tolerate protest and even sporadic unrest. They could not easily absorb unpredictability in consumption. Noncooperation disrupted the assumption that imperial markets would remain stable regardless of political conditions, revealing demand itself as a site of vulnerability.

Revenue anxiety followed closely behind commercial disruption and exposed the fiscal foundations of colonial rule. Customs duties on imported goods, excise taxes, and revenues tied to commercial activity formed a crucial component of colonial finance. As participation declined, revenue projections became harder to meet, complicating budgeting for administration, policing, and infrastructure. Officials faced mounting pressure to maintain services and control while managing declining or volatile income streams. These shortfalls did not immediately cripple the colonial state, but they forced administrators to confront the fragility of fiscal systems that depended on cooperation rather than compulsion. Economic refusal thus transformed political dissent into a budgetary problem, shifting resistance from the margins of governance into its accounting core.

Imperial correspondence and internal assessments reveal growing concern about the cumulative effects of noncooperation. Officials worried less about isolated losses than about the long-term erosion of confidence. Markets respond not only to present conditions but to expectations about the future. As noncooperation persisted, British firms hesitated to expand investment, and administrators questioned whether participation could be restored to previous levels even after repression subsided. Anxiety grew not because the empire was collapsing, but because it was becoming increasingly expensive and difficult to manage.

This economic unease also shaped political behavior. British authorities alternated between repression and concession, unsure which approach might restore stability. Excessive force risked deepening disengagement and provoking wider refusal, while accommodation risked signaling weakness and encouraging further demands. Noncooperation thus created a dilemma rather than a crisis. It denied the empire a decisive response by refusing confrontation. Economic anxiety replaced political certainty, and governance became reactive rather than confident. The empire remained intact, but its margins narrowed.

Imperial anxiety ultimately reflected recognition of a structural vulnerability at the heart of colonial power. British authority depended on predictable participation in economic systems that could not be enforced indefinitely without prohibitive cost. Noncooperation revealed that obedience, once withdrawn, could not be cheaply or sustainably restored through repression alone. Economic pressure did not overthrow the Raj, but it altered its operating conditions, forcing British authorities to govern under constant uncertainty and diminishing legitimacy. In doing so, noncooperation demonstrated that quiet withdrawal could reshape imperial power by making domination costly, unstable, and increasingly untenable.

Why Noncooperation Outlasted Confrontation

Noncooperation endured where confrontation repeatedly failed because it did not concentrate resistance in moments that could be decisively crushed. Armed revolts, strikes, and mass demonstrations created visible targets for repression and depended on rapid success to sustain participation. When these efforts stalled, fear, exhaustion, and retaliation quickly eroded support. Noncooperation avoided this vulnerability by dispersing resistance across time, space, and routine behavior. It did not require constant mobilization or dramatic sacrifice. Instead, it embedded refusal into daily life, allowing participation to continue even under repression and making total suppression impractical.

Confrontational movements also tended to escalate conflict in ways that ultimately strengthened imperial authority. Even limited violence allowed British officials to frame resistance as disorder, legitimizing emergency powers and harsh reprisals. This framing was not merely rhetorical; it reoriented the entire machinery of governance toward security, surveillance, and control, areas in which the empire possessed overwhelming advantages. Public debate shifted away from the legitimacy of rule toward the necessity of restoring order. Noncooperation denied the state this narrative terrain. By refusing confrontation, Gandhi’s strategy prevented the British from portraying resistance as rebellion or insurrection. Withdrawal appeared as a moral and civic decision rather than a criminal act, forcing authorities to confront disengagement rather than suppress an identifiable enemy.

Noncooperation proved more adaptable than confrontation because it could contract and expand without losing coherence or legitimacy. When leaders were arrested, organizations banned, or campaigns formally suspended, habits of refusal persisted in altered and less visible forms. Boycotts continued quietly in households and markets. Participation in colonial institutions did not fully resume even when public mobilization waned. This elasticity allowed noncooperation to absorb setbacks without collapsing. Confrontation depended on precise timing, centralized coordination, and sustained momentum, all of which were vulnerable to disruption. Noncooperation depended on normalization and endurance, making it resilient to leadership loss, repression, and temporary retreat.

Noncooperation outlasted confrontation because it aligned means with ends. Gandhi’s objective was not the seizure of power but the erosion of imperial legitimacy and the cultivation of self-rule. Withdrawal from imperial systems enacted that goal directly. Each act of refusal functioned simultaneously as resistance and preparation, training participants in self-discipline, mutual responsibility, and autonomy. Confrontation could challenge authority briefly. Noncooperation reshaped relationships. By targeting participation rather than power itself, it sustained pressure long after confrontational strategies exhausted their capacity to mobilize.

Rethinking Power in Anti-Colonial Struggle

The success of noncooperation requires a fundamental rethinking of how power operates in colonial contexts. Traditional accounts of resistance often emphasize confrontation, coercion, and the seizure of institutions as the primary routes to political change. Gandhi’s campaigns suggest a different model. Power did not reside solely in the instruments of force controlled by the colonial state. It was distributed across networks of participation that made governance possible. When those networks were disrupted through disciplined refusal, authority weakened without being directly challenged.

This perspective reframes anti-colonial struggle as a contest over participation rather than control, shifting the analytical focus away from dramatic confrontations and toward everyday compliance. British rule in India did not collapse because the empire lost its capacity to deploy violence. It eroded because it lost its ability to secure routine cooperation. Courts without litigants, schools without students, markets without consumers, and offices without staff exposed the dependence of imperial power on voluntary engagement. Noncooperation moved resistance into spaces that were difficult to police precisely because they appeared ordinary. Withdrawal from these systems did not announce itself as rebellion, yet it hollowed out the functional core of governance. The struggle was no longer over who commanded force, but over whether authority could continue to operate at all.

Rethinking power in this way also clarifies why noncooperation proved resistant to repression. Coercion can compel obedience temporarily, but it cannot generate the everyday participation that sustains complex systems of governance. Gandhi’s strategy exploited this asymmetry. By targeting participation itself, noncooperation undermined the functional basis of rule while remaining largely immune to decisive suppression. The British could punish refusal, but they could not easily reverse it once disengagement became normalized and morally justified within Indian society.

Noncooperation was not a secondary or symbolic form of resistance but a sophisticated strategy aligned with the realities of imperial governance. It recognized that power is relational and contingent, maintained through habit, legitimacy, and expectation rather than enforced continuously through violence. By withdrawing participation collectively and persistently, Indians transformed the struggle for independence into a reorganization of social behavior rather than a contest for immediate control of the state. This redefinition expanded the meaning of political action, making resistance accessible to millions and sustainable. Power, deprived of cooperation, did not collapse overnight. It eroded steadily, revealing that domination depends less on force than on the willingness of people to keep the system running.

Conclusion: When People Opt Out Together

Noncooperation in India demonstrated that power is most vulnerable not when it is attacked, but when it is quietly abandoned.

Gandhi’s campaigns revealed that imperial authority rested less on the visible machinery of repression than on the invisible habits of participation that sustained it. British rule did not collapse because its armies vanished or its officials fled. It weakened because everyday cooperation was withdrawn across markets, courts, schools, offices, and social rituals that had once normalized empire as inevitable. Each refusal increased the cost of governance. Each absence forced the state to rely more heavily on coercion, which in turn further eroded legitimacy. Power did not shatter. It thinned, stretched, and lost credibility as the distance between command and compliance widened.

The effectiveness of opting out together lay in its cumulative character. Individual acts of refusal were rarely dramatic, but their repetition across time and society transformed resistance from episodic protest into a structural condition. Noncooperation did not require constant mobilization once habits were established. Participation was replaced by patterned absence, and absence itself became political.

When people opt out together, power bleeds quietly and relentlessly.

Bibliography

- Ananda, S. “Swadeshi Movement in India and Its Impact on Freedom Struggle – a Study.” International Journal on Innovative Research in Technology 5:1 (2018): 389-392.

- Bayly, C. A. Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Brown, Judith M. Gandhi’s Rise to Power: Indian Politics 1915–1922. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972.

- Chandra, Bipan. India’s Struggle for Independence. New Delhi: Penguin, 1988.

- Gandhi, Mohandas K. Hind Swaraj and Other Writings. Edited by Anthony J. Parel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

- Hardiman, David. Gandhi in His Time and Ours. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

- Metcalf, Thomas R. The Aftermath of Revolt: India, 1857–1870. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.

- —-. Ideologies of the Raj. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Thompson, Andrew and Gary Magee. “A Soft Touch? British Industry, Empire Markets, and the Self-Governing Dominions, c. 1870-1914.” The Economic History Review 56:4 (2003):689-717.

- Tomlinson, B. R. The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Washbrook, David. “India, 1818–1860: The Two Faces of Colonialism.” In The Oxford History of the British Empire, vol. 3, edited by Andrew Porter, 395–421. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.03.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.