The clothing of men and women differed much less than in modern times.

By Dr. Harold Whetstone Johnston

Late Professor of Latin

Indiana University

Introduction

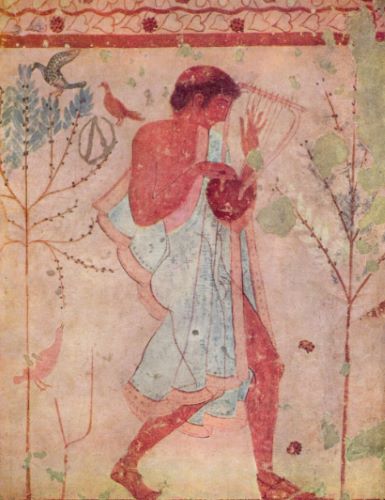

From the earliest to the latest times the clothing of the Romans was very simple, consisting ordinarily of two or three articles only besides the covering of the feet. These articles varied in material, style, and name from age to age, it is true, but were practically unchanged during the Republic and the early Empire. The mild climate of Italy and the hardening effect of the physical exercise of the young made unnecessary the closely fitting garments to which we are accustomed, while contact with the Greeks on the south and perhaps the Etruscans on the north gave the Romans a taste for the beautiful that found expression in the graceful arrangement of their loosely flowing robes.

The clothing of men and women differed much less than in modern times, but it will be convenient to describe their garments separately. Each article was assigned by Latin writers to one of two classes and called from the way it was put on indūtus or amictus. To the first class we may give the name of under garments, to the second outer garments, though these terms very inadequately represent the Latin words.

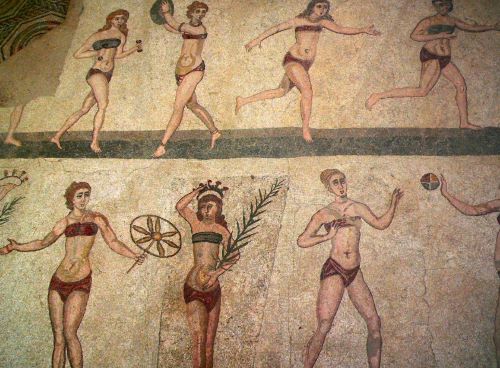

The Subligaculum

The subligāculum, is a loin-cloth familiar to us in pictures of ancient athletes and gladiators, or perhaps the short drawers (trunks), worn nowadays by bathers or college athletes. We are told that in the earliest times this was the only under garment worn by the Romans, and that the family of the Cethegi adhered to this ancient practice throughout the Republic, wearing the toga immediately over it. This, too, was done by individuals who wished to pose as the champions of old-fashioned simplicity, as for example the younger Cato, and by candidates for public office. In the best times, however, the subligāculum was worn under the tunic or replaced by it.

The Tunic

The tunic was also adopted in very early times and came to be the chief article of the kind covered by the word indūtus. It was a plain woolen shirt, made in two pieces, back and front, sewed together at the sides, and resembled somewhat the modern sweater. It had very short sleeves, covering hardly half of the upper arm. It was long enough to reach from the neck to the calf, but if the wearer wished for greater freedom for his limbs he could shorten it by merely pulling it through a girdle or belt worn around the waist. Tunics with sleeves reaching to the wrists (tunicae manicātae), and tunics falling to the ankles (tunicae tālārēs) were not unknown in the late Republic, but were considered unmanly and effeminate.

The tunic was worn in the house without any outer garment and probably without a girdle; in fact it came to be the distinctive house-dress as opposed to the toga, the dress for formal occasions only. It was also worn with nothing over it by the citizen while at work, but he never appeared in public without the toga over it, and even then, hidden by the toga though it was, good form required the wearing of the girdle with it. Two tunics were often worn (tunica interior, or subūcula, and tunica exterior), and persons who suffered from the cold, as did Augustus for example, might wear a larger number still when the cold was very severe. The tunics intended for use in the winter were probably thicker and warmer than those worn in the summer, though both kinds were of wool.

The tunic of the ordinary citizen was the natural color of the white wool of which it was made, without trimmings or ornaments of any kind. Knights and senators, on the other hand, had stripes of purple, narrow and wide respectively, running from the shoulder to the bottom of the tunic both behind and in front. These stripes were either woven in the garment or sewed upon it. From them the tunic of the knight was called tunica angustī clāvī (or angusticlāvia), and that of the senator lātī clāvī (or lāticlāvia). Some authorities think that the badge of the senatorial tunic was a single broad stripe running down the middle of the garment in front and behind, but unfortunately no picture has come down to us that absolutely decides the question. Under this official tunic the knight or senator wore usually a plain tunica interior. When in the house he left the outer tunic unbelted in order to display the stripes as conspicuously as possible.

Besides the subligāculum and the tunica the Romans had no regular underwear. Those who were feeble through age or ill health sometimes wound strips of woolen cloth (fasciae) around the legs for the sake of additional warmth. These were called feminālia or tībiālia according as they covered the upper or lower part of the leg. Such persons might also use similar wrappings for the body (ventrālia) and even for the throat (fōcālia), but all these were looked upon as the badges of senility or decrepitude and formed no part of the regular costume of sound men. It must be especially noticed that the Romans had nothing corresponding to our trousers or even long drawers, the braccae or brācae being a Gallic article that was not used at Rome until the time of the latest emperors. The phrase nātiōnēs brācātae in classical times was a contemptuous expression for the Gauls in particular and barbarians in general.

The Toga

Overview

Of the outer garments or wraps the most ancient and the most important was the toga (cf. tegere). Whence the Romans got it we do not know, but it goes back to the very earliest time of which tradition tells, and was the characteristic garment of the Romans for more than a thousand years. It was a heavy, white, woolen robe, enveloping the whole figure, falling to the feet, cumbrous but graceful and dignified in appearance. All its associations suggested formality. The Roman of old tilled his fields clad only in the subligāculum; in the privacy of his home or at his work the Roman of every age wore the comfortable, blouse-like tunica; but in the forum, in the comitia, in the courts, at the public games, everywhere that social forms were observed he appeared and had to appear in the toga. In the toga he assumed the responsibilities of citizenship, in the toga he took his wife from her father’s house to his, in the toga he received his clients also toga-clad, in the toga he discharged his duties as a magistrate, governed his province, celebrated his triumph, and in the toga he was wrapped when he lay for the last time in his hall. No foreign nation had a robe of the same material, color, and arrangement; no foreigner was allowed to wear it, though he lived in Italy or even in Rome itself; even the banished citizen left the toga with his civil rights behind him. Vergil merely gave expression to the national feeling when he wrote the proud verse (Aen. I, 282):

Rōmānōs, rērum dominōs, gentemque togātam.

The Romans, lords of deeds, the race that wears the toga.

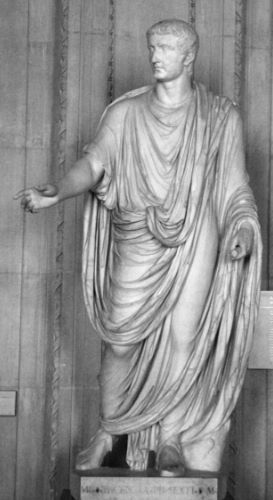

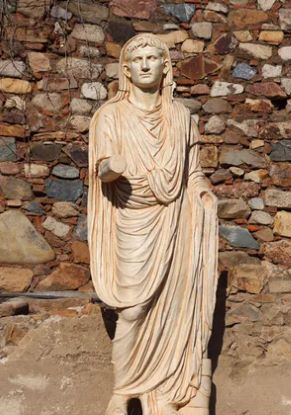

Form and Arrangement

The general appearance of the toga is known to every schoolboy; of few ancient garments are pictures so common and in general so good. They are derived from numerous statues of men clad in it, which have come down to us from ancient times, and we have besides full and careful descriptions of its shape and of the manner of wearing it in the works of writers who had worn it themselves. As a matter of fact, however, it has been found impossible to reconcile the descriptions in literature with the representations in art and scholars are by no means agreed as to the precise cut of the toga or the way it was put on. It is certain, however, that in its earlier form it was simpler, less cumbrous, and more closely fitted to the figure than in later times, and that even as early as the classical period its arrangement was so complicated that the man of fashion could not array himself in it without assistance.

Scholars who lay the greater stress on the literary authorities describe the cut and arrangement of the toga about as follows: It consisted of one piece of cloth of semicircular cut, about five yards long by four wide, a certain portion of which was pressed into long narrow plaits. This cloth was doubled lengthwise, not down the center but so that one fold was deeper than the other. It was then thrown over the left shoulder in such a manner that the end in front reached to the ground, and the part behind was in length about twice a man’s height. This end was then brought around under the right arm and again thrown over the left shoulder so as to cover the whole of the right side from the armpit to the calf. The broad folds in which it hung over were thus gathered together on the left shoulder. The part which crossed the breast diagonally was known as the sinus, or bosom. It was deep enough to serve as a pocket for the reception of small articles. According to this description the toga was in one piece and had no seams.

Those who attempt the reconstruction of the toga wholly or chiefly from works of art find it impossible to reproduce on the living form the drapery seen on the statues, with a toga of one piece of goods or of a semicircular pattern. An experimental form resembles that of a lamp shade cut in two and stretched out to its full extent. The dotted line GC is the straight edge of the goods; the heavy lines show the shape of the toga after it had been cut out, and had had sewed upon it the ellipse-like piece marked FRAcba. The dotted line GE is of a length equivalent to the height of a man at the shoulder, and the other measurements are to be calculated proportionately. When the toga is placed on the figure the point E must be on the left shoulder, with the point G touching the ground in front. The point F comes at the back of the neck, and as the larger part of the garment is allowed to fall behind the figure the points L and M will fall on the calves of the legs behind, the point a under the right elbow, and the point b on the stomach. The material is carried behind the back and under the right arm and then thrown over the left shoulder again. The point c will fall on E, and the portion OPCa will hang down the back to the ground. The part FRA is then pulled over the right shoulder to cover the right side of the chest and form the sinus, and the part running from the left shoulder to the ground in front is pulled up out of the way of the feet, worked under the diagonal folds and allowed to fall out a little to the front. It will be found in practice, however, that much of the grace of the toga must have been due to the trained vestiplicus, who kept it properly creased when it was not in use and carefully arranged each fold after his master had put it on. We are not told of any pins or tapes to hold it in place, but are told that the part falling from the left shoulder to the ground behind kept all in position by its own weight, and that this weight was sometimes increased by lead sewed in the hem.

It is evident that in this fashionable toga the limbs were completely fettered, and that all rapid, not to say violent, motion was absolutely impossible. In other words the toga of the ultrafashionable in the time of Cicero was fit only for the formal, stately, ceremonial life of the city. It is easy to see, therefore, how it had come to be the emblem of peace, being too cumbrous for use in war, and how Cicero could sneer at the young dandies of his time for wearing “sails not togas.” We can also understand the eagerness with which the Roman welcomed a respite from civic and social duties. Juvenal sighed for the freedom of the country, where only the dead had to wear the toga. Martial praises the unconventionality of the provinces for the same reason. Pliny makes it one of the attractions of his villa that no guest need wear the toga there. Its cost, too, made it all the more burdensome for the poor, and the working classes could scarcely have worn it at all.

The earlier toga must have been simpler by far, but no certain representation of it has come down to us. The Dresden statue, often used to illustrate its arrangement, is more than doubtful, the garment being probably a Greek mantle of some sort. An approximate idea of it may be gained perhaps from a statue in Florence of an Etruscan orator, which corresponds very closely with the descriptions of it in literary sources. At any rate it was possible for men to fight in it by tying the trailing ends around the body and drawing the back folds over the head. This was called the cinctus Gabīnus, and long after the toga had ceased to be worn in war this cinctus was used in certain ceremonial observances.

Kinds of Togas

The toga of the ordinary citizen was, like the tunic, of the natural color of the white wool of which it was made, and varied in texture, of course, with the quality of the wool. It was called toga pūra (or virīlis, lībera). A dazzling brilliancy could be given to the toga by a preparation of fuller’s chalk, and one so treated was called toga splendēns or candida. In such a toga all persons running for office arrayed themselves, and from it they were called candidātī. The curule magistrates, censors, and dictators wore the toga praetexta, differing from the ordinary toga only in having a purple border. It was also worn by boys and by the chief officers of the free towns and colonies.

The toga picta was wholly of purple covered with embroidery of gold, and was worn by the victorious general in his triumphal procession and later by the Emperors. The toga pulla was simply a dingy toga worn by persons in mourning or threatened with some calamity, usually a reverse of political fortune. Persons assuming it were called sordidātī and were said mūtāre vestem. This vestis mūtātiō was a common form of public demonstration of sympathy with a fallen leader. In this case curule magistrates contented themselves with merely laying aside the toga praetexta for the toga pūra, and only the lower orders wore the toga pulla.

Wraps

The Lacerna

In Cicero‘s time there was just coming into fashionable use a mantle called lacerna, which seems to have been first used by soldiers and the lower classes and then adopted by their betters on account of its convenience. These wore it at first over the toga as a protection against dust and sudden showers. It was a woolen mantle, short, light, open at the sides, without sleeves, but fastened with a brooch or buckle on the right shoulder. It was so easy and comfortable that it began to be worn not over the toga but instead of it, and so generally that Augustus issued an edict forbidding it to be used in public assemblages of citizens.

Under the later Emperors, however, it came into fashion again, and was the common outer garment at the theaters. It was made of various colors, dark naturally for the lower classes, white for formal occasions, but also of brighter hues. It was sometimes supplied with a hood (cucullus), which the wearer could pull over the head as a protection or a disguise. No representation of the lacerna in art has come down to us that can be positively identified; that in Rich s.v. is very doubtful. The military cloak, first called the trabea, then palūdāmentum and sagum, was much like the lacerna, but made of heavier material.

The Paenula

Older than the lacerna and used by all sorts and conditions of men was the paenula, a heavy coarse wrap of wool, leather, or fur, used merely for protection against rain or cold, and therefore never a substitute for the toga or made of fine materials or bright colors. It seems to have varied in length and fullness, but to have been a sleeveless wrap, made in one piece with a hole in the middle, through which the wearer thrust his head. It was, therefore, classed with the vestīmenta clausa, or closed garments, and must have been much like the modern poncho. It was drawn on over the head, like a tunic or sweater, and covered the arms, leaving them much less freedom than the lacerna did.

In those of some length there was a slit in front running from the waist down, and this enabled the wearer to hitch the cloak up over one shoulder, leaving one arm comparatively free, but at the same time exposing it to the weather. It was worn over either tunic or toga according to circumstances, and was the ordinary traveling habit of citizens of the better class. It was also commonly worn by slaves, and seems to have been furnished regularly to soldiers stationed in places where the climate was severe. Like the lacerna it was sometimes supplied with a hood.

Other Wraps

Of other articles included under the general term amictus we know little more than the names. The synthesis was a dinner dress worn at table over the tunic by the ultrafashionable, and sometimes dignified by the special name of vestis cēnātōria, or cēnātōrium alone. It was not worn out of the house except on the Saturnalia, and was usually of some bright color. Its shape is unknown. The laena and abolla were very heavy woolen cloaks, the latter being a favorite with poor people who had to make one garment do duty for two or three. It was used especially by professional philosophers, who were proverbially careless about their dress. One is thought to be worn by the man on the extreme left, in the picture of a school shown in. The endormis was something like the modern bath robe, used by men after violent gymnastic exercise to keep from taking cold, and hardly belongs under the head of dress.

Footgear

Solae

It may be set down as a rule that freemen did not appear in public at Rome with bare feet, except as nowadays under the compulsion of the direst poverty. Two styles of footwear were in use, slippers or sandals (soleae) and shoes (calceī). The slipper consisted essentially of a sole of leather or matting attached to the foot in various ways. Custom limited its use to the house and it went characteristically with the tunic, when that was not covered by an outer garment. Oddly enough, it seems to us, the slippers were not worn at meals. Host and guests wore them into the dining-room, but as soon as they had taken their places on the couches slaves removed the slippers from their feet and cared for them until the meal was over. Hence the phrase soleās poscere came to mean “to prepare to take leave.” When a guest went out to dinner in a lectīca he wore the soleae, but if he walked he wore the regular out-door shoes (calceī) and had his slippers carried by a slave.

Calcei

Out of doors the calceus was always worn, although it was much heavier and less comfortable than the solea. Good form forbade the toga to be worn without the calceī, and they were worn also with all the other garments included under the word amictus. The calceus was essentially our shoe, made on a last of leather, covering the upper part of the foot as well as protecting the sole, fastened with laces or straps. The higher classes had shoes peculiar to their rank. The shoe for senators is best known to us (calceus senātōrius); but we know only its shape, not its color. It had a thick sole, was open on the inside at the ankle, and was fastened by wide straps which ran from the juncture of the sole and the upper, were wrapped around the leg and tied above the instep. The mulleus or calceus patricius was worn originally by patricians only, but later by all curule magistrates. It was shaped like the senator’s shoe, was red in color like the fish from which it was named, and had an ivory or silver ornament of crescent shape (lūnula) fastened on the outside of the ankle.

We know nothing of the shoe worn by the knights. Ordinary citizens wore shoes that opened in front and were fastened by a strap of leather running from one side of the shoe near the top. They did not come up so high on the leg as those of the senators and were probably of uncolored leather. The poorer classes naturally wore shoes of coarser material, often of untanned leather (pērōnēs), and laborers and soldiers had half-boots (caligae) of the stoutest possible make, or wore wooden shoes. No stockings were worn by the Romans, but persons with tender feet might wrap them with fasciae to keep the shoes and boots from chafing them.

Head Coverings

Men of the upper classes in Rome had ordinarily no covering for the head. When they went out in bad weather they protected themselves, of course, with the lacerna and paenula, and these were provided with hoods (cucullī). If they were caught without wraps in a sudden shower they made shift as best they could by pulling the toga up over the head. Persons of lower standing, especially workmen who were out of doors all day, wore a conical felt cap called the pilleus. It is probable that this was a survival of what had been in prehistoric times an essential part of the Roman dress, for it was preserved among the insignia of the oldest priesthoods, the Pontifices, Flamines, and Salii, and figured in the ceremony of manumission.

Out of the city, that is, while traveling or while in the country, the upper classes, too, protected the head, especially against the sun, with a broad-brimmed felt hat of foreign origin, the causia or petasus. They were worn in the city also by the old and feeble, and in later times by all classes in the theaters. In the house, of course, the head was left uncovered.

Hair and Beard

The Romans in early times wore long hair and full beards, as did all uncivilized peoples. Varro tells us that professional barbers came first to Rome in the year 300 B.C., but we know that the razor and shears were used by the Romans long before history begins. Pliny says that the younger Scipio (†129 B.C.) was the first of the Romans to shave every day, and the story may be true. People of wealth and position had the hair and beard kept in order at home by their own slaves, and these slaves, if skillful barbers, brought high prices in the market. People of the middle class went to public barber shops, and made them gradually places of general resort for the idle and the gossiping. But in all periods the hair and beard were allowed to grow as a sign of sorrow, and were the regular accompaniments of the mourning garb already mentioned. The very poor, too, went usually unshaven and unshorn, simply because this was the cheap and easy fashion.

Styles varied with the years of the persons concerned. The hair of children, boys and girls alike, was allowed to grow long and hang around the neck and shoulders. When the boy assumed the toga of manhood the long locks were cut off, sometimes with a good deal of formality, and under the Empire they were often made an offering to some deity. In the classical period young men seem to have worn close clipped beards; at least Cicero jeers at those who followed Catiline for wearing full beards, and on the other hand declares that their companions who could show no signs of beard on their faces were worse than effeminate. Men of maturity wore the hair cut short and the face shaved clean. Most of the portraits that have come down to us show beardless men until well into the second century of our era, but after the time of Hadrian (117-138 A.D.) the full beard became fashionable.

Jewelry

The ring was the only article of jewelry worn by a Roman citizen after he reached the age of manhood, and good taste limited him to a single ring. It was originally of iron, and though often set with a precious stone and made still more valuable by the artistic cutting of the stone, it was always worn more for use than ornament. The ring was in fact in almost all cases a seal ring, having some device upon it which the wearer imprinted in melted wax when he wished to acknowledge some document as his own, or to secure cabinets and coffers against prying curiosity. The iron ring was worn generally until late in the Empire, even after the gold ring had ceased to be the special privilege of the knights and had become merely the badge of freedom. Even the engagement ring was usually of iron, the setting giving it its material value, although we are told that this particular ring was often the first article of gold that the young girl possessed.

Of course there were not wanting men as ready to violate the canons of taste in the matter of rings as in the choice of their garments or the style of wearing the hair and beard. We need not be surprised, then, to read of one having sixteen rings, or of another having six for each finger. One of Martial’s acquaintances had a ring so large that the poet advised him to wear it on his leg, and Juvenal tells us of an upstart who wore light rings in the summer and heavy rings in the winter. It is a more surprising fact that the ring was worn on the joint, not pressed down as far as possible on the finger, as we wear them now. If two were worn on the same finger they were worn on separate joints, not touching each other. This fashion must have seriously interfered with the movement of the finger.

Women’s Fashion

Overview

It has been remarked already that the dress of men and women differed less in ancient than in modern times, and we shall find that in the classical period at least the principal articles worn were practically the same, however much they differed in name and probably in the fineness of their materials. At this period the dress of the matron consisted in general of three articles: the tunica interior, the tunica exterior or stola, and the palla. Beneath the tunica interior there was nothing like the modern corset-waist or corset, intended to modify the figure, but a band of soft leather (mamillāre) was sometimes passed around the body under the breasts for a support, and the subligāculum was also worn by women.

The Tunica Interior

The tunica interior did not differ much in material or shape from the tunic for men already described. It fitted the figure more closely perhaps than the man’s, was sometimes supplied with sleeves, and as it reached only to the knee did not require a belt to keep it from interfering with the free use of the limbs. A soft sash-like band of leather (strophium), however, was sometimes worn over it, close under the breasts, but merely to support them, and in this case we may suppose that the mamillāre was discarded. For this sash the more general terms zōna and cingulum are sometimes used. This tunic was not usually worn alone, even in the house, except by young girls.

The Stola

Over the tunica interior was worn the tunica exterior, or stola, the distinctive dress of the Roman matron. It differed in several respects from the tunic worn as a house-dress by men. It was open at both sides above the waist and fastened on the shoulders by brooches. It was much longer, reaching to the feet when ungirded and having in addition a wide border or flounce (īnstita) sewed to the lower hem. There was also a border around the neck, which seems to have been usually of purple. The stola was sleeveless if the tunica interior had sleeves, but if the tunic itself was sleeveless the stola had them, so that the arm was always protected. These sleeves, however, whether in tunic or stola, were open on the front of the upper arm and only loosely clasped with brooches or buttons, often of great beauty and value.

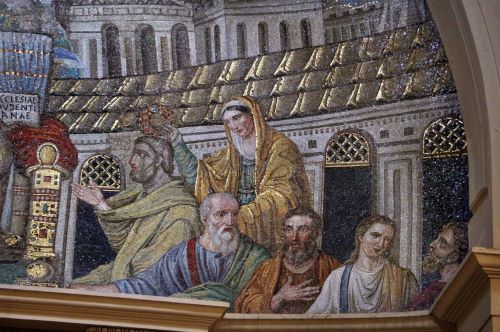

Owing to its great length the stola was always worn with a girdle (zōna) above the hips, and through it the stola itself was pulled until the lower edge of the īnstita barely cleared the floor. This gave the fullness about the waist seen in the statue of Faustina, in which the cut of the sleeves can also be seen. The zōna was usually entirely hidden by the overhanging folds. The stola was the distinctive dress of the matron, as has been said, and it is probable that the īnstita was its distinguishing feature; that is, the tunica exterior of the unmarried woman had no flounce or border, though it probably reached to the floor.

The Palla

The palla was a shawl-like wrap for use out of doors. It was a rectangular piece of woolen goods, as simple as possible in its form, but worn in the most diverse fashions in different times. In the classical period it seems to have been wrapped around the figure, much as the toga was. One-third was thrown over the left shoulder from behind and allowed to fall to the feet. The rest was carried around the back and brought forward either over or under the right arm at the pleasure of the wearer. The end was then thrown back over the left shoulder after the style of the toga, or allowed to hang loosely over the left arm, as in the statue of Livia. It was possible also to pull the palla up over the head, and this method of using it is supposed by some scholars to be shown in the statue of Livia, while others see in the covering of the head some sort of a veil.

Shoes and Slippers

What has been said of the footgear of men applies also to that of women. Slippers (soleae) were worn in the house, differing from those of men only in being embellished as much as possible, sometimes even with pearls. An idea of their appearance may be had from the statue of Faustina. Shoes (calceī) were insisted upon for out-door use, and differed from those of men, as they chiefly differ from them now, in being made of finer and softer leather. They were often white, or gilded, or of bright colors, and those intended for winter wear had sometimes cork soles.

Hair Dressing

The Roman woman regularly wore no hat, but covered the head when necessary with the stola or with a veil. Much attention was given to the arrangement of the hair, the fashions being as numerous and as inconstant as they are to-day. For young girls the favorite arrangement, perhaps, was to comb the hair back and gather it into a knot (nōdus) on the back of the neck. For matrons it will be sufficient to call attention to the figures already given, and to show from statues five styles worn at different times under the Empire, all belonging to ladies of the court.

For keeping the hair in position pins were used of ivory, silver, and gold, often mounted with jewels. Nets (rēticula) and ribbons (vittae, taeniae, fasciolae) were also worn, but combs were not made a part of the head-dress. The Roman woman of fashion did not scruple to color her hair, the golden-red color of the Greek hair being especially admired, or to use false hair, which had become an article of commercial importance early in the Empire. Mention should also be made of the garlands (corōnae) of flowers, or of flowers and foliage, and of the coronets of pearls and other precious stones that were used to supplement the natural or artificial beauty of the hair.

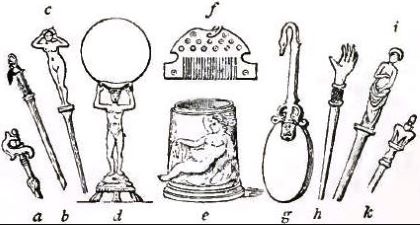

The woman’s hairdresser was a female slave, and Juvenal tells us that she suffered cruelly from the impatience of her mistress, who found the long hairpins shown in the figure a convenient instrument of punishment, The ōrnātrīx was an adept in all the tricks of the toilet already mentioned, and besides used all sorts of unguents, oils, and tonics to make the hair soft and lustrous and to cause it to grow abundantly. Above are shown a number of common toilet articles: a, b, c, h, i, and k are hairpins, d and g are hand mirrors made of highly polished metal, f is a comb, and e a box for pomatum or powder.

Accessories

The parasol (umbrāculum, umbella) was commonly used by women at Rome at least as early as the close of the Republic, and was all the more necessary because they wore no hats or bonnets. The parasols were usually carried for them by attendants. From vase paintings we learn that they were much like our own in shape, and could be closed when not in use. The fan (flābellum) was used from the earliest times and was made in various ways); sometimes of wings of birds, sometimes of thin sheets of wood attached to a handle, sometimes of peacock’s feathers artistically arranged, sometimes of linen stretched over a frame. These fans were not used by the woman herself, being always handled by an attendant who was charged with the task of keeping her cool and untroubled by flies. Handkerchiefs (sūdāria), the finest made of linen, were used by both sexes, but only for wiping the perspiration from the face or hands. For keeping the palms cool and dry ladies seem also to have used glass balls, or balls of amber, the latter, perhaps, for the fragrance also.

The Roman woman was passionately fond of jewelry, and incalculable sums were spent upon the adornment of her person. Rings, brooches, pins, jeweled buttons, and coronets have been mentioned already, and besides these bracelets, necklaces, and ear-rings or pendants were worn from the earliest times by all who could afford them. Not only were they made of costly materials, but their value was also enhanced by the artistic workmanship that was lavished upon them. Almost all the precious stones that are known to us were familiar to the Romans and were to be found in the jewel-casket of the wealthy lady. The pearl, however, seems to have been in all times the favorite. No adequate description of these articles can be given here; no illustrations can do them justice. It will have to suffice that Suetonius says that Caesar paid six million sesterces (nearly $300,000) for a single pearl, which he gave to Servilia, the mother of Marcus Brutus, and that Lollia Paulina, the wife of the Emperor Caligula, possessed a single set of pearls and emeralds which is said by Pliny the elder to have been valued at forty million sesterces (nearly $2,000,000).

Dress of Children and Slaves

Schoolboys wore the subligāculum and tunica, and it is probable that no other articles of clothing were worn by either boys or girls of the poorer classes. Besides these, children of well-to-do parents wore the toga praetexta, which the girl laid aside on the eve of her marriage and the boy when he reached the age of manhood.

Slaves were furnished a tunic, wooden shoes, and in stormy weather a cloak, probably the paenula. This must have been the ordinary garb of the poorer citizens of the working classes, for they would have had little use for the toga, at least in later times, and could hardly have afforded so expensive a garment.

Materials, Colors, and Manufacture

Fabrics of wool, linen, cotton, and silk were used by the Romans. For clothes woolen goods were the first to be used, and naturally so, for the early inhabitants of Latium were shepherds, and woolen garments best suited the climate. Under the Republic wool was almost exclusively used for the garments of both men and women, as we have seen, though the subligāculum was frequently, and the woman’s tunic sometimes, made of linen. The best native wools came from Calabria and Apulia, that from near Tarentum being the best of all. Native wools did not suffice, however, to meet the great demand, and large quantities were imported. Linen goods were early manufactured in Italy, but were used chiefly for other purposes than clothing until in the Empire, and only in the third century of our era did men begin to make general use of them.

The finest linen came from Egypt, and was as soft and transparent as silk. Little is positively known about the use of cotton, because the word carbasus, the genuine Indian name for it, was used by the Romans for linen goods also and when we meet the word we can not always be sure of the material meant. Silk, imported from China directly or indirectly, was first used for garments under Tiberius, and then only in a mixture of linen and silk (vestēs sēricae). These were forbidden for the use of men in his reign, but the law was powerless against the love of luxury. Garments of pure silk were first used in the third century.

White was the prevailing color of all articles of dress throughout the Republic, in most cases the natural color of the wool, as we have seen. The lower classes, however, selected for their garments shades that required cleansing less frequently, and found them, too, in the undyed wool. From Canusium came a brown wool with a tinge of red, from Baetica in Spain a light yellow, from Mutina a gray or a gray mixed with white, from Pollentia in Liguria the dark gray (pulla) used, as has been said, for public mourning. Other shades from red to deep black were furnished by foreign wools. Almost the only artificial color used for garments under the Republic was purple, which seems to have varied from what we call crimson, made from the native trumpet-shell (būcinum or mūrex), to the true Tyrian purple. The former was brilliant and cheap, but liable to fade. Mixed with the dark purpura in different proportions, it furnished a variety of permanent tints.

One of the most popular of these tints, violet, made the wool cost some $20 a pound, while the genuine Tyrian cost at least ten times as much. Probably the stripes worn by the knights and senators on the tunics and togas were much nearer our crimson than purple. Under the Empire the garments worn by women were dyed in various colors, and so, too, perhaps, the fancier articles worn by men, such as the lacerna and the synthesis. The trabea of the augurs seems to have been striped with scarlet and purple, the palūdāmentum of the general to have been at different times white, scarlet, and purple, and the robe of the triumphātor purple.

In the old days the wool was spun at home by the maidservants working under the eye of the mistress, and woven into cloth on the family loom, and this was kept up throughout the Republic by some of the proudest families. Augustus wore these home-made garments. By the end of the Republic, however, this was no longer general, and while much of the native wool was worked up on the farms by the slaves directed by the vīlica, cloth of any desired quality could be bought in the open market. It was formerly supposed that the garments came from the loom ready to wear, but this is now known to have been incorrect. We have seen that the tunic was made of two separate pieces sewed together, that the toga had probably to be fitted as carefully as a modern coat, and that even the coarse paenula could not have been woven or knitted in one piece. But ready-made garments were on sale in the towns as early as the time of Cato, though perhaps of the cheaper qualities only, and in the Empire the trade reached large proportions. It is remarkable that with the vast numbers of slaves in the familia urbāna it never became usual to have soiled garments cleansed at home. All garments showing traces of use were sent by the well-to-do to the fullers (fullōnēs) to be washed, whitened (or re-dyed), and pressed. The fact that almost all were of woolen materials made skill and care all the more necessary.

Chapter 7 from The Private Life of the Romans, by Harold Whetstone Johnston (1903), published by Project Gutenberg to the public domain.