Ancient and medieval societies lacked the bureaucratic sophistication of modern states, but their loyalty screenings reveal similar anxieties.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Fragile Threshold of Belonging

The modern state often imagines itself unique in its elaborate systems of border control and loyalty vetting. Yet long before passports and biometric scans, ancient and medieval societies developed their own mechanisms for determining whether newcomers could be trusted.

What we call “loyalty screenings” today found their equivalents in oaths sworn to civic gods, forced displays of piety, ritual participation, and long service in military or economic life. These practices were not bureaucratic in the modern sense, but they were deeply political. They reveal how precarious the category of belonging has always been, and how societies across time have devised strategies to test the fidelity of outsiders.

Antiquity: Sacrifice and the Civic Oath

Greek City-States and Suspicion of the Foreigner

The Greek polis was a fiercely exclusive community. Citizenship was a guarded privilege, and foreigners could not easily cross into the civic body. At Athens, a resident alien or metic had to secure sponsorship, pay a special tax, and often swear loyalty to the polis in ceremonies that invoked both gods and laws. Refusal to acknowledge the civic cult was tantamount to political treason. The unity of religion and politics meant that participation in sacrifice was itself a loyalty test. To abstain was not an act of conscience alone but a signal of disloyalty to the community itself.1

The case of Christians in the later Roman Empire illustrates this dynamic. Their refusal to sacrifice to the emperor’s genius was read not simply as religious difference but as subversion of Roman order. Loyalty here was not judged by political statements but by willingness to perform religious ritual. The test of faith doubled as a test of political belonging.2

Rome and the Sacramentum

Rome perfected this logic of oaths and service. Non-citizens recruited into the Roman military had to swear the sacramentum, an oath of absolute fidelity to the emperor. This was no empty formality. The oath made personal loyalty to the ruler the defining marker of reliability. Over time, auxiliary soldiers who completed decades of service were rewarded with citizenship, their loyalty proven not only in words but in endurance.3

Such practices reveal a Roman understanding of loyalty as cumulative and demonstrated. Citizenship could be earned, but only by the long submission of body and will to imperial authority. Trust was not presumed. It was cultivated and measured across time.

Medieval Europe: Conversion, Gender, and Purity

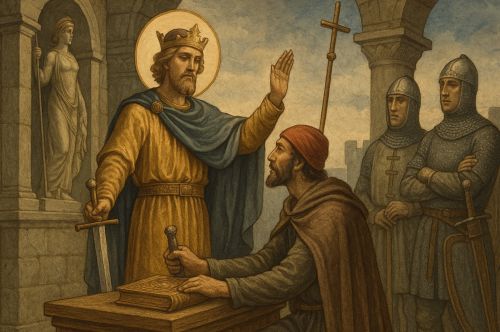

The Weight of the Oath

In medieval Europe, loyalty screening often came through public oaths to lords, kings, or towns. Guilds and municipalities required newcomers to swear fidelity before being allowed to trade or reside. The oath was simultaneously legal and spiritual, binding the swearer under threat of both earthly and divine sanction. To kiss the cross or swear upon relics was to place oneself under the surveillance of heaven and earth alike.4

Conversion and Suspicion

Nowhere were such screenings more fraught than in the case of religious converts. In medieval Spain, Jews and Muslims who converted to Christianity were often suspected of insincerity. The Inquisition later developed mechanisms to test and probe such conversions, turning loyalty to the faith into a political category. Entire families were judged across generations under statutes of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood), a form of loyalty screening that fused theology with ancestry.5

Women bore particular burdens in this culture of suspicion. Since patriarchal theology often cast women as spiritually weak, their conversions were doubly scrutinized. A converted woman was not merely judged as a Christian, but as a mother whose children might be “tainted” if her loyalty were doubted. Screening extended not only to individuals but to entire lineages, making the boundary between insider and outsider perpetual and unstable.

The Islamic World: Dhimma and Conditional Belonging

The Pact of Protection

Under Islamic rule, Christians and Jews could remain within the empire, but only under conditions of loyalty. Known as dhimmi, these communities were granted protection if they paid the jizya tax and acknowledged subordination. Here loyalty screening took the form of compliance with financial and social restrictions. Non-Muslims could live, work, and worship, but they could not proselytize, bear arms against Muslims, or openly defy the political order.6

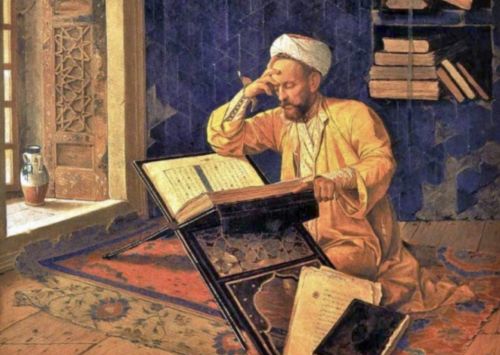

Converts and Tests of Faith

Conversion to Islam was both a gateway to opportunity and a site of suspicion. Fresh converts sometimes had to demonstrate sincerity by reciting prayers correctly or adopting Islamic ritual practices under scrutiny. Service in military or bureaucratic posts often became the ultimate test of loyalty. To be trusted in positions of authority was itself a certification of fidelity, earned over years of proven devotion.7

Patterns Across Civilizations

Despite their differences, Greece, Rome, medieval Christendom, and the Islamic caliphates shared common strategies. Oaths, rituals, and service all acted as proxies for trust. Religion was frequently employed as a political test, since worship could be monitored publicly in ways that private conviction could not. Service, whether in the army or guild, provided long-term demonstration of loyalty. Taxes, sacrifices, or participation in rituals created paper-thin but enforceable markers of belonging.

The fragility of knowledge and culture played its role as well. Just as technologies vanished when tied too tightly to secret traditions, so too could trust dissolve when political or religious conditions shifted. What mattered most was not truth of belief, but visible compliance. Loyalty was screened not by conscience but by action.

Conclusion: The Unending Anxiety of Belonging

Ancient and medieval societies lacked the bureaucratic sophistication of modern states, but their loyalty screenings reveal similar anxieties. Communities feared infiltration, disloyalty, and betrayal, and so demanded proof through sacrifice, oaths, and service. These rituals made loyalty visible, yet they also created permanent suspicion. Converts could never be fully trusted. Outsiders bore the burden of proof across generations.

To study these practices is to recognize continuity in human political life. Belonging has always been conditional. Trust has always been tested. What we call immigration policy today is only the latest version of a far older question: how do communities decide who may enter, and on what terms.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Josiah Ober, Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 118–122.

- Candida Moss, The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (New York: HarperOne, 2013), 45–51.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 214–220.

- M.T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1979), 104–110.

- Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Assimilation and Racial Anti-Semitism: The Iberian and the German Models (New York: Leo Baeck Institute, 1982), 23–29.

- Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 57–62.

- Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, Volume 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 282–285.

Bibliography

- Ando, Clifford. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Clanchy, M.T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. Oxford: Blackwell, 1979.

- Cohen, Mark R. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Hodgson, Marshall. The Venture of Islam, Volume 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

- Moss, Candida. The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. New York: HarperOne, 2013.

- Ober, Josiah. Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Yerushalmi, Yosef Hayim. Assimilation and Racial Anti-Semitism: The Iberian and the German Models. New York: Leo Baeck Institute, 1982.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.