In 1384 about a hundred people were arrested in election violence.

By Dr. Brad Kirkland

Medieval Scholar

Rotten Boroughs

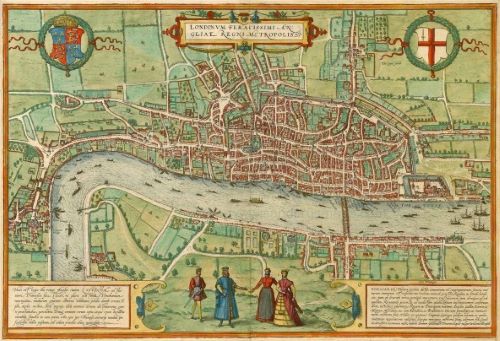

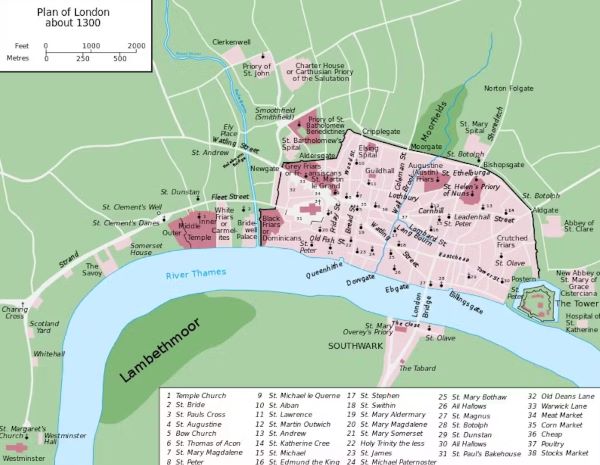

The medieval riots I study came about because of conflicts between the supporters of two London mayors: Nicholas Brembre, a wealthy entrepreneurial politician, and John Northampton, a middling merchant whose policies were popular with London’s working class. John Northampton became mayor of London in 1381, immediately following the Peasants’ Revolt – appointed, probably, in part because both the royal and civic governments recognised his popularity with the common people.

Northampton spent the next two terms attacking what he saw as corruption in government and trade practices – and he especially attacked the monopolies of traders in food. These actions were very popular among London’s workers, but when he began to seek out corruption among his allies’ trades, his support waned.

Then, when Nicholas Brembre came into office in 1383, it sparked a shake-up of the craft and trade groups given influence under Northampton. The leaders of those groups were accused of being lightweight, their decisions arrived at “by clamour rather than by reason”. They were replaced by men elected by the wards, effectively robbing many trades of their voice in London’s politics.

As George Galloway would tell you this year, no one likes to lose an election, and Northampton and his supporters attempted to overturn the vote, but were refused. Resentment grew steadily and after several months Northampton had the support to launch the largest civic protest in London since the Peasants’ Revolt.

Popular Unrest

Then, when Nicholas Brembre came into office in 1383, it sparked a shake-up of the craft and trade groups given influence under Northampton. The leaders of those groups were accused of being lightweight, their decisions arrived at “by clamour rather than by reason”. They were replaced by men elected by the wards, effectively robbing many trades of their voice in London’s politics.

As George Galloway would tell you this year, no one likes to lose an election, and Northampton and his supporters attempted to overturn the vote, but were refused. Resentment grew steadily and after several months Northampton had the support to launch the largest civic protest in London since the Peasants’ Revolt.

When Brembre was re-elected in October, a second riot occurred outside the Guildhall. Much like the protests we saw in London over the weekend, some were there because they (mistakenly) believed that their grievances would be heard, while others came with the express purpose of fomenting unrest. A tailor called William Wodecok was arrested after rushing out of his home with a sword, a buckler and a polearm (pike) – hoping to use them all in a riot.

Many of those arrested were imprisoned for speaking ill of the mayor and so it can be interpreted that they were, like the majority of London’s modern protesters, peaceful, if forthright.

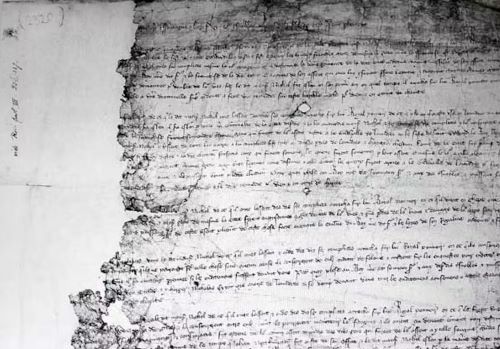

Ultimately, the crafts involved in this riot had legitimate grievances. And their leadership later collectively petitioned parliament for action be taken against Nicholas Brembre for his misgovernment. Their charges were heard, and Brembre was hanged for his crimes in 1388, some four years after the disturbances.

Originally published by The Conversation, 05.11.2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.