By Dr. Robert D. Miller II, O.F.S.

Ordinary Professor of Old Testament

Associate Dean for Graduate Studies

The Catholic University of America

Recent studies in oral tradition have shown that many societies produced oral and written literature simultaneously. Such a model for biblical literature proposes that a tale circulating by word of mouth only was virtually unknown, just as a tale circulating by text only was equally rare. Written texts circulated in spoken form by recitation long after they were committed to writing. And those recited forms spawned oral forms that were never in writing, or were not put in writing for some time afterwards. Ancient Near Eastern and ethnographic societies in similar situations also provide information on performance contexts for the oral component of this interplay.

Biblical scholarship often speaks of “oral tradition” quite loosely, as if the concept is commonly and easily understood. We imagine a time when Israel was illiterate, before writing, when traditions were handed down from generation to generation by elders or priests. Modern scholarship on orality provides a more reliable scenario, both with regard to the interplay of orality and literacy and for the “performance contexts” of oral tradition.

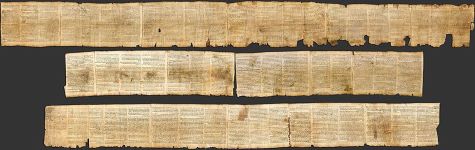

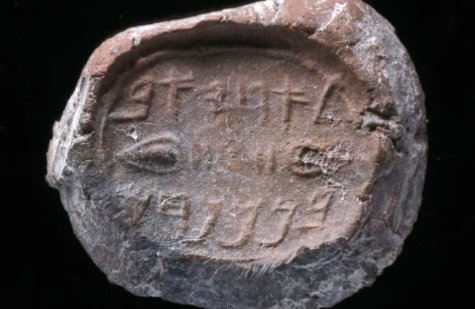

Let us begin with literacy. Considerable evidence exists for literacy in 8th and 7th century Israel and Judah1. This evidence includes numerous administrative seals (e.g., LMLK seals), vulgar script, and writings by common soldiers and landlords (e.g., Lachish letter 3). The number of inscriptions increased dramatically from the mid-8th century onward. Substantial evidence also suggests scribal schools in this period. The meticulous Hebrew palaeography, consistent spelling, and the use of the complicated Egyptian hieratic numeral system all suggest sophisticated knowledge of trained professionals.

Yet even in the 8th and 7th centuries, as Karel van der Toorn writes, “determining the level of literacy in the ancient Near East is not a matter of merely accumulating percentages and figures2”. It is a “quite misleading matter of whether or not writing was ‘available’ to the poets and audiences3”. Epigraphic remains from Israel are primarily ostraca. Most ostracon texts are ephemeral letters or economic documents kept for a short time before being transcribed, if at all, on to something permanent4. Ostraca could not accommodate Belles lettres, and there are only two examples of ink-written West Semitic literary texts, the Ahiqar papyrus and the Deir Allah wall plaster. Literature, even in the late pre-exilic period, was oral literature.

“Reports from fieldwork as well as from text-based analysis of oral-derived documents have exposed the insufficiency of the concept of a Great Divide between two mutually exclusive media, revealing binary opposition as a misleading, reductive approximation5”. Recent field studies in oral tradition and folklore have shown many societies produced oral and written literature simultaneously. Oral tradition and written literature are related phenomena, and in fact, writing often supports oral tradition and vice-versa.

For example, ancient Egypt displays various relationships between written and oral literature. Works composed in writing were intended for performance, especially in the Middle Kingdom (2100-1650 B.C.). “In several of the royal burial suites where Pyramid Texts are inscribed, each column begins with ‘to be spoken,’ marking the whole as being for recitation; what is written is an ideal oral form6”. Writing served functions more fetish or ritual than communicative7. Even in later Egyptian wisdom texts, the fictional audiences described in the “texts are very often groups of people, suggesting that the poems were intended for audiences rather than single readers8”. At the same time, written works of literature drew on other written works.

In Mesopotamia, too, oral tradition existed alongside written literature. The Old Assyrian Sargon legend (19th century B.C.) has Sargon say, “Why should I elaborate on a tablet” (lines 63-64) the stories well known orally9? Even long after literature was committed to writing, it was written ana zamāri, for singing10. Atrahasis (17th century B.C.) is not a tale, but a zamāru, a ballad (8.16-19). A thousand years later, the Song of Erra (8th century B.C.) still refers to its singers (5.49.53-54). Written texts developed as improvisations based on recitation aids like storylines, plot elements, and narrative excerpts11.

In early Judaism, singing the laws was the norm (tosefta Oholot 16.8; t. Para 4.7; Rabbi Jonathan, Megilla 32a). The absence of space between words, offset poetic lines, or chapter and verse breaks would have made the Old Testament a “highly reader-unfriendly manuscript12”. Scrolls were a storage system for texts kept in memory, akin to a computer backup directory, although recitation aids were included in the text in the form of repetition, inclusios, and other devices 13.

In the Middle Ages, musical accents were added even to the Mishnah to ensure oral preservation (e.g., the Parma [B] manuscript of the Order Toharot; the Sabbionetta edition of m. Qidd.). Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai is attributed as saying, “He who reads without melody and repeats without song, concerning him the scripture says: ‘Therefore I gave them statutes which were not to their advantage’” (b. Meg. 32a).

In fact, illiterate societies are not the most common source of oral literature. “The largest majority of the examples of oral literature which we possess and analyse have not been collected from pure [oral] cultures14”. Some of this literature has been collected from societies that have recently become literate but preserve much orality, but there are also many societies that have been literate from antiquity and yet oral literature has continued to flourish15. And in Israel both before and after the Exile, as in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece (Plato, Phaedrus, 275C, D; 276D), ancient literate audiences “still preferred and even expected to experience their literature orally16”.

In the model I propose for biblical literature, a tale circulating by word of mouth only was virtually unknown, just as a tale circulating by text only was equally rare17. Written texts circulated in spoken form by recitation long after they were committed to writing. And those recited forms spawned oral forms that were never in writing, or were not put in writing for some time afterwards. Oral texts that circulated from singer to audience or singer to singer could be recorded in writing, could be consulted by writers, could be consulted by singers of other stories18.

Older models viewed the literary process as linear. First, there were oral stories that circulated among singers or storytellers. Eventually, these were written down. Those texts, perhaps as soon as they were written, were recited or chanted orally to the illiterate masses, a process that continued through the Masoretic vocalization, and on into the Mishnaic period (b. Šabb. 96b; Baba Meşia 92). This process was called “re-oralization”.

We must abandon this model. The process is not nearly so linear and cannot be in a society that knew of writing long before the 12th century B.C. and commonly employed oral literature long after the 5th 19.

The interplay of written and oral is complex. I found it most useful to bring in comparands from Iceland. Biblical scholars have a long history of interest in the Icelandic literature, and with good reason. As with Israel, the original context of composition and recitation of the material are lost to us, reconstructible only through scenes created in the text itself much later than the material’s origin. As with the Old Testament’s narrative books, there has been a long debate between those who argued for primarily written origins of the Icelandic sagas and those who maintained they were in essence orally derived, written versions of oral tradition. Like the narrative books of the Old Testament, the Icelandic family sagas drew on both oral poems and written stories, many of them from continental Europe (several important sagas are shaped according to episodes of the Nibelungenlied; Njáls Saga even borrows from the writings of Gregory the Great). And yet, the sagas are not the work of writers drawing solely on other writers 20. Statistical analysis of the sagas indicates even writers deeply indebted to written material and written literary structure were still dependent to a reasonable extent on oral tradition 21.

If the “literature” of pre-exilic Israel and Judah was predominantly oral, then a mode of thought distinct from the literary was operative in employing that oral literature. When we study supposed orally derived passages from the Old Testament — we need a distinct set of tools: what is now called performance criticism 22. We would not imagine a musicologist who only studied scores or a scholar who studied ancient Greek dramas never seeing them performed.

Performance criticism is a kind of discourse analysis that explores how oral discourse occurs in a particular setting that has recognizable norms of organization and distinctive functions determined by social and cultural conventions familiar to the original performer and audience 23. Oral literature “rejects any analysis that would dissociate it from within its social function and from its socially accorded place – more than a written text would 24”. Oral texts emerge in contexts in which they were performed and these contexts are not only dictated by environment but emerge in social negotiations between participants 25. Whitney Shiner’s study of the use of voice and gesture in Quintilian shows how setting, vocal modulation, and gestures radically affect the meaning of the “text” 26. In short, performance is anchored in and inseparable from its context 27.

This is a grim but edifying realization. In the remainder of this essay, let me reconstruct these performance contexts for Israelite oral narrative poetry 28. Ancient Near Eastern evidence helps a great deal here. But for the ancient past, where we cannot look at a real spectator, if we want to avoid merely casting ourselves in that role, we must find ways to deal with practices that are of necessity located in the contingent realities of actual performances 29. Ethnography is chief among these ways 30. Folklorist Lauri Honko writes, “The only way out of this dilemma seems to be more and better empirical studies on living oral epic traditions, a careful comparison of the results and their cautious application to other epics whose performance contexts will always remain poorly known but may be elucidated with the help of comparisons 31”.

In ancient Egypt, performative texts use the verbs “recite” (šdỉ) or “pronounce” (dm)32. Singing is depicted graphically in such settings33, with the singers engaged in stylized poses34 and vertical harps akin to Assyrian harps35. Contents of their oral literature include personal memoires, humorous morality tales, and encomia to the king36. One example of the latter from the court of Merneptah involves singing accompanied by harp37. A court setting is commonly depicted, and singer-audience interaction is important for composition38. Accomplished singers (mdw.ty) could attain fame for their skill, as did Setepibre-ankh in the court of Amenemhet II39.

The fullest presentation of a performance context is in the text King Cheops and the Magicians of Papyrus Westcar40. Extant copies are from the Hyksos period but it is a Middle Kingdom composition41. The story relates how in the court of King Khufu (Cheops), “The king’s son Khafra arose [to speak, and he said: I should like to relate to your majesty] another marvel, one which happened in the time of [your] father, Nebka” (1.16-20). He then tells a sort of “marvel tale”. This is followed by: “Bauefre arose to speak, and he said: Let me have [your] majesty hear a marvel which took place in the time of your father King Snefru” (4.18-20). There are two more such tales42. A favorable response from Khufu accompanies each, which encourages and molds the performance of the next one. Although we cannot assume this is an accurate record of real court practices43, here we see a depiction of a court setting, the status of the accomplished singer, and the interplay of audience and singer in the composition-in-performance.

Within various Mesopotamian texts, there are numerous prologues like “I will sing…” and epilogues such as “Whoever recites this text…” 44. Some texts (e.g., Dumuzi and Enkidu) are designated balbale, composed with lyrics45 Atrahasis is written “for singing”, and Anne Kilmer has extensively explored how this would have been done46. Harps (sammû) are abundantly attested in iconography, especially from the Assyrian period47. A lyre, unlike a harp, has a yoke. An authentic reproduction of the Sumerian “Lyre of Ur” has been constructed and tuned according to Anne Kilmer’s guidelines. This lyre can be heard online, played as per Kilmer, but unfortunately only either accompanied by replica Sumerian pipes, at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LvgtAHV4mzw, or accompanied by English recitation of Gilgamesh, at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TSWEeBGhz4M. The sound of the lyre resembles how postbiblical literature described the nēbel, a low rumble.

Some Hittite texts are labeled “ballads” (išhamai)48. One of these ballads, the Song of Illuyanka (Contexts of Scripture 1.150-51 #1.56; CTH 321), is to be performed in the Hittite Purulli festival49. The Song of the Ullikummi is in Hurrian “sung” (šir-ad-ilu), before an audience (lines 1-7), probably accompanied by music50. Twenty-nine Hurrian ballads were found at Ugarit with both words and musical notation, and a rendition can be heard at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=viMbnj_Ei2A51.

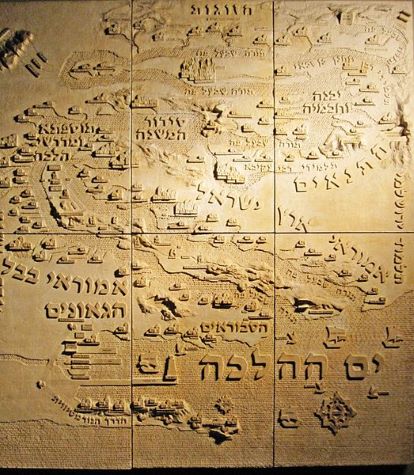

For the Levant, we have much less information. The author of the Egyptian story of Wen-Amun thought it plausible to depict an Egyptian woman singer performing in the court at Byblos (2.68-69). From Ugarit, only The Birth of the Beautiful and Gracious Gods (CTA 23 = KTU 1.23) gives indication that it was performed dramatically52. But there are a number of texts that refer to harp playing and singing within the narrative53. A performance scene is found in the Ugaritic Baal cycle. In Anat 1 = 4AB (KTU/CAT 1.3.i = CTA 3.1), at a feast in Baal’s court:

He stood, chanted [yabuddu] and sang [yašîru],

Frame drums [maşillatâmi] in the virtuoso’s hands

Sweet of voice the hero sang,

About Baal on the summit of Zaphon (lines 18-22)54.

This is similar to the Papyrus Westcar example, Merneptah’s court, and to several ethnographic examples I will turn to shortly.

Lyre players are depicted among the Judean captives being deported from Lachish by Sennacherib, who records receiving singers in tribute from Hezekiah55. Other images of lyres were found at Megiddo (one nine-stringed from the 13th century and another on a Philistine vase from the late 10th century), Kuntillet Ajrud (9th century), Ashdod, and Jerusalem (twelve-stringed, on a 7th-century seal)56. The Megiddo and Kuntillet Ajrud lyres are similar in design57. Frame drums are known from figurines from Beth Shean, 9th-century Tell Taanach, 9th-century Tell el-Farah North, and 8th-century Tel Shiqmona58. There are images of small portable lyres in early postexilic seals59.

Ethnography gives a similar portrait of performance contexts for oral literature, including audience-singer interaction, variety of delivery modes, court setting, and even the harp. As I have shown elsewhere, the best ethnographic analogy to ancient Israelite balladry is Icelandic poetry 60, although this, too, is ancient and there are thus no ethnographic accounts of performances61. There are accounts of performances found in some sagas, but we must use these cautiously as they reveal only the authors’ perceptions of performance62. Nevertheless, what is evident in such descriptions is the same interplay of audience and singer as in the Egyptian examples 63. The singer is encouraged in his own reconstitution by the audience’s interaction64.

The tale of Norna-Gestr recounts the arrival of an anonymous stranger at a chieftain’s court and his entertaining the court with sung/chanted poetic stories, accompanied by a harp. In a nearly identical setting, the Roman historian Priscus of Panium (Historia, Fragment 8) describes a singer’s storytelling in the court of Attila the Hun as “singing” with harp65. The presence or absence of music with Icelandic poetry is an open question66, but anthropologically, “Music … is an indispensable element in the performance of oral literature, particularly oral epics67”.

The verb used for the performance of Icelandic poetry is usually translated “chant”, but its precise meaning is unclear68. Oral balladry must often have been accompanied by explanatory remarks in prose 69, body language 70, and “all aspects of the singer’s art are called into use, including the wide and flexible spectrum of vocal utterance: plain speech, heightened speech, sung speech, spoken song, simple syllabic song, melismatic song, as well as the more radical elements of human vocal sound71”.

Sagas also illustrate serial performance, portions of a longer story given in discrete settings or units, a phenomenon probable for Icelandic poetry72 and for Homer73.

With caution, we can examine the Bible’s own picture of oral performance. As John Miles Foley writes of Homer, “We have not lost all of the keys to performance. If as audience or readers we are prepared to decode the signals that survive … then performance can still be keyed by these features74”.

The biblical kinnôr and nēbel are likely both lyres, not harps or lutes, although kinnôr seems in some places to be a generic term for all stringed instruments75. The ᶜasor, in light of comparative philology (Akk eširtu) and some early Christian texts, might have been the Assyrian-style harp, borrowed into Syro-Palestine76. The frame drum is the Heb. tōp77.

There are numerous references in the biblical narratives to musical performance. Theodore Burgh’s thoroughgoing analysis of such passages outlines two categories78. His “Style A”, more common in the Pentateuch and Deuteronomistic History, involves varied performers and performance spaces. His “Style B”, mainly in Chronicles, involves specific musical personnel and performance spaces and times. Both styles use a variety of instruments, although Style A is more prone to frame drums79. Burgh’s analysis joins Othmar Keel’s note that the only instance in which a nēbel does not also require a kinnôr with it is in royal Psalm 144: the kinnôr was more common and used by ordinary worshippers (Ps 43:3)80. The nēbel is primarily associated with the First Temple81.

Still, the risk in applying this information is that we are looking at mere musical performance. The singing of hymns, love songs, war rallying cries, and the like is not oral performance of narrative poetry and court ballads82, although both seem to be designated, šîr. The kinnôr in particular accompanied narrative recitation. There are passages that envision performance settings for oral historical narrative. As with Icelandic sagas and Cheops and the Magicians, we are dealing with the author’s own perceptions of performance, yet commonly, “The narrative’s described performance is often closely and deliberately connected to the immediate performance space in which the story itself was told83”.

Post-battle celebrations typically include commemoration in ballad, as did Baal’s feast in the Ugaritic material. Exemplars are Exodus 15 (the “Song of the Sea”) and Judges 5 (the “Song of Deborah”). Mark Smith notes the use of yetannû from tānāh in Judg 5:11 with the meaning “commemoration” for this root, as in Judg 11:4084. Post-battle laments are also attested (2 Sam 2:19-25a; Zeph 2:14-18; Baal in KTU 1.2.iv 6-7 and KTU 1.5.v)85.

Oral-and-literate ancient Israel probably had performance settings that were standardized for its oral narrative literature. These performance contexts, based on biblical and ancient Near Eastern evidence, probably conform to the Icelandic portrait that applies also for Cheops and the Magicians and other texts. We should envision a court setting for the performance. The purpose of much of this material – some of it performed serially – would have been to praise or otherwise support the ruler, either directly or secondarily. Audience-singer interaction would have been of great importance in determining the form of the performed material. Finally, music, especially but not exclusively harp and lyre, would have accompanied recitation, chanting, or singing. The content of this material, and its relationship to the Old Testament, are future questions.

Endnotes

- J. Schaper, “A Theology of Writing” in Anthropology and Biblical Studies, ed. C. Lawrence and M. Aguilar, Leiden, Deo, 2004, p. 103.

- K. van der Toorn, Scribal Culture and the Making of the Hebrew Bible Cambridge, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 2007, p. 10.

- J. M. Foley, Singer of Tales in Performance, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 72.

- M. S. Jaffee, Torah in the Mouth: Writing and Oral Tradition in Palestinian Judaism 200 BCE–400 CE, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 15.

- J. M. Foley, “Verbal Marketplaces and the Oral-Literary Continuum”, in: S. Ranković (ed.), Along the Oral-Written Continuum, Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 20, Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, p. 17.

- J. Baines, Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 150s.

- E. Teeter, “The Potency of Writing in Ancient Egypt”, in C. Woods (ed.), Visible Language (= Oriental Institute Museum Publications, 32), Chicago, Oriental Institute, 2010, p. 156.

- R. B. Parkinson, “Individual and Society in Middle Kingdom Literature”, in A. Loprieno (ed.) Ancient Egyptian Literature (= Probleme der Ägyptologie 10), Leiden, Brill, 1996, p. 143.

- J. G. Westenholz, “Historical Events and the Process of their Transformation in Akkadian Heroic Traditions”, in D. Konstan, K. A. Raaflaub (eds), Epic and History, The Ancient World: Comparative Histories, 4, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, p. 30.

- A. Kilmer, “Fugal Features of Atrahasis”, in M. E. Vogelzang, H. L. J. Vanstiphout (eds.) Mesopotamian Poetic Language, (= Cuneiform Monographs, 6), Groningen (Styx) 1996, p. 133.

- E. Mundal, “How Did the Arrival of Writing Influence Old Norse Oral Culture?” in S. Ranković (ed.), Along the Oral-Written Continuum (= Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 20), Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, p. 171; Westenholz, “Historical Events”, p. 30.

- D. Carr, Writing on the Tablets of the Heart, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 4.

- P. Achtemeier, “Omne Verbum Sonat”, Journal of Biblical Literature 109, 1990, p. 17.

- Finnegan, “How Oral is oral literature?”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 37, 1974, p. 52-64 (p 53, italics original).

- S. Ranković, “The Oral-Written Continuum as a Space”, in: id., Along the Oral-Written Continuum (= Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 20), Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, p. 39.

- E. W. and P. T. Barber, When they Severed Earth from Sky, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 151; italics original; Green, Medieval Listening and Reading, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 30; R. Scodel, “Social Memory in Aeschylus’ Oresteia”, in Orality, Literacy, Memory in the Ancient Greek and Roman World (= Mnemosyne Supplement, 298), Leiden, Brill, 2008, p.118.

- This was understood by some biblical scholars long ago; e.g., G. W. Ahlström, “Oral and Written Transmission”, Harvard Theological Review 59, 1966, passim, esp. p. 70.

- Mundal, “How …”, p. 170.

- Ranković, “Oral-Written Continuum”, p. 43.

- Mundal, “How…”, p. 163, 166.

- Ranković, “Oral-Written Continuum”, p. 46f.

- T. Giles and W. Doan, “Performance Criticism of the Old Testament”, Religion Compass 2, 2008, p. 273; Finnegan, Oral and Beyond, p. 78; Oral Traditions, p. 93.

- B. Patridge, Discourse Analysis, New York, Continuum, 2006, p. 82f.

- P. Zumthor, Oral Poetry. An Introduction, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1990; Finnegan, Oral Traditions, 43; Giles and Doan, “Performance Criticism”, p. 276.

- N. Fairclough, Critical Discourse Analysis, London, Longman, 1995, p. 192.

- W. Shiner, “Oral Performance in the New Testament World”, in H. E. Hearon and P. Ruge-Jones (eds.), The Bible in Ancient and Modern Media, Eugene, OR, Cascade, 2009, pp. 49-63.

- C. Bazerman, Shaping Written Knowledge, Madison, WI, University of Wisconsin Press, 1988, p. 7.

- I use the term “narrative poetry” as opposed to “oral prose,” although one cannot exclude rather prosaic oral literature, akin to what is called “Prosimetrum” in European studies. At least one Icelandic saga (see below) performed in 1119 was prosimetrical; J. Harris, “The Prosimetrum of Icelandic Saga and Some Relatives”, in J. Harris and K. Reichl (eds.) Prosimetrum, Rochester, D. S. Brewer, 1997, p. 145. If we define Prosimetrum as a range of compositional practices between prose and poetry, the category works well for much biblical material; S. Weitzman, “The ‘Orientalization’ of Prosimetrum”, in: J. Harris and K. Reichl (eds.), Prosimetrum, Rochester, D. S. Brewer, 1997, p. 230f.

- Zerubavel, Time Maps, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2003, p. 29.

- Foley, “Analogues”, in: Id. (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Epic, Oxford, Blackwell, 2005, p. 199.

- Honko, “Comparing the Textualization”, p. 2; Rosalind Thomas, “Performance Literature and the Written Word”, Oral Tradition 20, 2005, p. 5.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, p. 160f.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, p. 197.

- A. Schlott, “Eine Beobachtung zu Mimik und Gestik von Singenden”, Göttinger Miszellen 152, 1996, pp. 55, 57, 59–63, 69, figs. 3 (V Dynasty grave of En-cheft-ka), 6 (grave of Amanamhet [Thutmosis III]), 15 (XII Dynasty grave of Uchotep).

- B. Lawergren and O. R. Gurney, “Sound Holes and Geometrical Figures”, Iraq 49, 1987, p. 37.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, 169, 183. For example, lines 2-14 of the Song to Merneptah from Hermopolis presented by Günther Roeder, “Zwei hieroglyphische Inschriften aus Hermopolis”, Annales du Service des Antiquités d’Égypte, 52, 1954, pp. 328–340.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, p. 188.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, p. 187.

- Redford, “Scribe and Speaker”, p. 190.

- English translation by W. K. Simpson in id. (ed.), The Literature of Ancient Egypt, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1973, pp. 15-30.

- Á. S. Rodríguez, El Papiro Westcar, Seville, Ediciones ASADE, 2003. 1; J. Berggren, The ‘Ipwt in Papyrus Westcar (7, 5-8; 9,1-5), Diss. (Uppsala University) 2006, 2. Hans Goedick has challenged a date so early; “Thoughts about the Papyrus Westcar”, Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 120, 1993, p. 23-24.35.

- Originally, there were at least five tales; only the last words of the first are preserved, the second and fifth have lacunae, and the third and fourth are complete; Berggren, ‘Ipwt, p. 2.

- H. M. Hays, “The Historicity of Papyrus Westcar”, Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 129, 2002, pp. 20-30; Parkinson, “Individual and Society”, p. 141.

- M. E. Vogelzang, “Some Aspects of Oral and Written Tradition in Akkadian”, in: M. E. Vogelzang and H. L. J. Vanstiphout (eds.), Mesopotamian Epic Literature, Lewiston, NY, Edwin Mellen Press, 1992, p. 266.

- R. J. Dumbrill, The Archaeomusicology of the Ancient Near East, Victoria, British Columbia, Trafford Publishing, 2005, p. 399.

- “Fugal Features of Atrahasis”, in Mesopotamian Poetic Language, in: M. E. Vogelzang and H. L. J. Vanstiphout (eds.), Cuneiform Monographs 6, Groningen, Styx, 1996, p. 133 and passim.

- Dumbrill, Archaeomusicology, 182, 218; Lawergren and Gurney, “Sound Holes”, 40. A lyre, unlike a harp, is characterized by a yoke. The lyre is probably the ALGAR; Dumbrill, Archaeomusicology, 241. Y. Kolyada, A Compendium of Musical Instruments and Instrumental Terminology in the Bible, London, Equinox, 2009, p. 44.

- G. Beckman, “Hittite and Hurrian Epic”, in: J. M. Foley (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Epic, Chichester,Wiley-Blackwell, 2005, p. 256.

- G. Beckman, “The Anatolian Myth of Illuyanka”, Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 14, 1982, p. 18; id., “The Religion of the Hittites”, Biblical Archaeologist 52, 1989, p. 104. On the oral-tradition stream from this myth to the Old Testament, see Miller, “Origin”.

- A. Archi, “Transmission of Recitative Literature by the Hittites”, Altorientalische Forschungen 34, 2007, p. 198f.

- Dumbrill, Archeaomusicology, p. 23f.

- Sasson, “Literary Criticism”, 94.

- N. Wyatt, Word of Tree and Whisper of Stone (= Gorgias Ugaritic Studies, 1), Piscataway, Gorgias Press, 2007, p. 136.

- English translation of M. Smith, “Warrior Culture in Early Israel and the ‘Voice’ of David in 1 Samuel 2”, paper presented at the Catholic Biblical Association annual meeting, Omaha NE, 2009. He notes the absence of women in such a public feast, in contrast to those in the private feast of ANEP #157.

- O. Keel, The Symbolism of the Biblical World, Winona Lake, Eisenbranns, 1997, fig. 470.

- T. W. Burgh, Listening to the Artifacts: Music Culture in Ancient Palestine, New York, T & T Clark, 2006, p. 10f; Kolyada, Compendium, p. 10f.

- Burgh, Listening, p.14.

- Catalogued in Burgh, Listening, pp. 31-37.

- Dumbrill, Archaeomusicology, figs. 103-104.

- R. D. Miller II, Oral Tradition in Ancient Israel (= Biblical Performance Criticism, 4), Eugene, OR (Cascade) 2011. Cf. J. Jesch, “The Once and Future King”, in: S. Ranković (ed.), Along the Oral-Written Continuum, (= Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 20), Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, p. 104; J. Harris, “Old Norse Memorial Discourse between Orality and Literacy”, in: Id., p. 122; V. Ólason, “The Poetic Edda”, in Along the Oral-Written Continuum, in: Id., p. 252.

- T. Gunnell, “The Performance of the Poetic Edda”, in: S. Brink (ed.), The Viking World, New York, Routledge, 2008, p. 300.

- Mitchell, “Reconstructing”, p. 203; O’Donoghue, Skaldic Verse, p. 15. Stefanie Würth is particularly skeptical about learning anything from such testimonies; see S. Würth, “Skaldic Poetry and Performance”, in: J. Quinn, K. Heslop, and T. Wills (eds.), Learning and Understanding in the Old Norse World, (= Cultures of Northern Europe 18), New York, Brepols, 2007, p. 266. The situation is similar to the performances depicted in Anglo-Saxon sources. While they are not a reliable picture, they attest to a literate audience’s perception of an oral situation that is clearly identical to real ancient Germanic oral practice; Niles, “Myth”, p. 12, 37; also M. Amodio, Writing the Oral Tradition, Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 2004, p. 39.

- Mundal, “How”, p. 166; Harris, “Prosimetrum”, p. 134.

- Gordon, “Oral Tradition”, p. 73; J. Lindow, “Þættir and Oral Performance”, in: W. F. H. Nicolaisen (ed.), Oral Tradition in the Middle Ages (= Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 112), Binghamton, State University of New York at Binghamton, 1995, p. 184.

- English text in Eyewitness to History (ed. John Carey), Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1987, pp. 23-25. On the parity of this example with the Anglo-Saxon and Norse cases, see Jeff Opland, Anglo-Saxon Oral Poetry, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1980, p. 51, 63.

- Harris, “Performance”, pp. 228-230.

- H. L. Sakata, “The Musical Curtain: Music as Structural Marker in Epic Performance”, in: The Oral Epic (= Intercultural Music Studies, 12), Berlin, Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 2000, p. 159

- E. O. G. Turville-Petre, Scaldic Poetry, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1976, p. lxxvi.

- Harris, “Prosimetrum”, p. 131.

- Mundal, “How…”, p. 177.

- B. Bagby, “Beowulf, the Edda, and the Performance of Medieval Epic”, in: E. B. Vitz, N. F. Regalado, and M. Lawrence (eds.), Performing Medieval Narrative, Woodbridge, Suffolk, D. S. Brewer, 2005, p. 186. Bagby’s performance of Beowulf in this style can be found at http://www.nyu.edu/projects/mednar/ file.php?id=1019.

- Lindow, “Þættir”, pp. 180-183.

- On Homer, see M. L. West, “The Singing of Homer and the Modes of Early Greek Music”, Journal of Hellenic Studies 101, 1981, pp. 113-115 and passim; Scodel, Listening to Homer, pp. 58, 78f., 176f.; K. Reichl, “Introduction: The Music and Performance of Oral Epics”, in The Oral Epic (= Intercultural Music Studies, 12), Berlin, (Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung) 2000, p. 2. The performance contexts are likely identical; G. Nagy, “Epic as Music”, in: ibid., pp. 55, 61.

- Singer of Tales in Performance, p. 64, italics original.

- Keel, Symbolism, p. 346f.; Kolyada, Compendium, p. 32.

- Kolyada, Compendium, pp. 29-31.

- Kolyada, Compendium, p. 106.

- Listening to the Artifacts, p. 108.

- Burgh, Listening to the Artifacts, pp. 108-111, 117. Causse, Plus Vieux, p. 23, n.1 undertook similar analyses.

- Keel, Symbolism, p. 349.

- Kolyada, Compendium, p. 42.

- C. Meyers, “Women with Hand-Drums, Dancing: Bible”, in: P. Hyman and D. Ofer (eds.), Jewish Women, online edition at http://jwa.org/encyclopedia. In which category do we place the descendents of Jubal, all who play the lyre and pipe? Cf. Causse, Plus Vieux, p. 32.

- Gunnell, “Narratives, Space and Drama”, p. 13.

- Smith, “Warrior Culture”; he also notes the parallels of Iliad 9.

- Smith, “Warrior Culture”.

Originally published by Revue des sciences religieuses 86:2 (2012), DOI:https://doi.org/10.4000/rsr.1467 under the terms of an Open Access license, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.