Montelius indicated his belief in the potential of prehistoric Chinese archaeology and the discoveries about to be made.

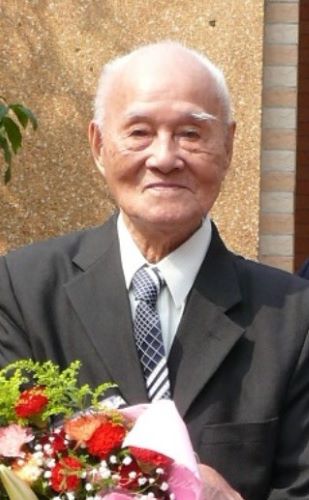

By Dr. Xingcan Chen

Professor of Archaeology

Senior Research Fellow and Director of the Institute of Archaeology

Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Beijing)

By Dr. Magnus Fiskesjö

Associate Professor of Anthropology

Cornell University

Abstract

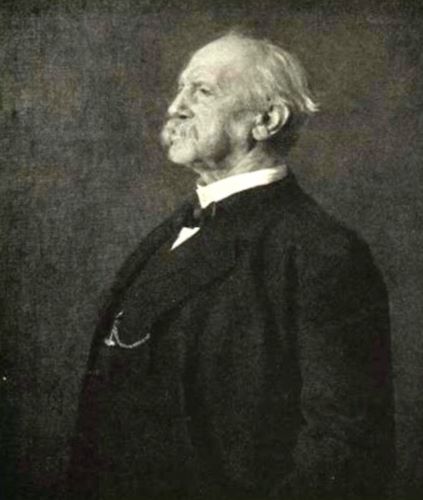

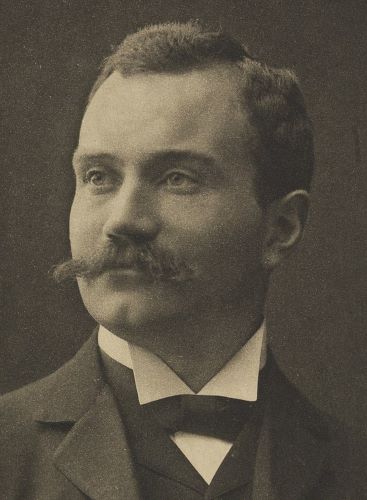

This paper demonstrates that Oscar Montelius (1843–1921), the world-famous Swedish archaeologist, had a key role in the development of modern scientific Chinese archaeology and the discovery of China’s prehistory. We know that one of his major works, Die Methode, the first volume of his Älteren kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa, translated into Chinese in the 1930s, had considerable influence on generations of Chinese archaeologists and art historians. What has previously remained unknown, is that Montelius personally promoted the research undertaken in China by Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960), whose discoveries of Neolithic cultures in the 1920s constituted the breakthrough and starting point for the development of prehistoric archaeology in China. In this paper, we reproduce, translate and discuss a long forgotten memorandum written by Montelius in 1920 in support of Andersson’s research. In this Montelius indicated his belief in the potential of prehistoric Chinese archaeology as well as his predictions regarding the discoveries about to be made. It is therefore an important document for the study of the history of Chinese archaeology as a whole.

Introduction: Montelius in China

We are all familiar with the work of Oscar Montelius (1843–1921), which occupies a central position in the history of world archaeology. Even eight decades after his death, exhibits in Sweden’s Museum of National Antiquities (Historiska Museet) continue to use the ‘Montelius System’, with Bronze Age exhibits arranged according to his six-age schema.1 Montelius’ contributions to archaeology were manifold, but his influence was strongest in the field of typological research (see Daniel 1981; Åström 1995; Baudou 2012).2 His work in this field greatly influenced Chinese archaeology, which received inspiration and indeed sustenance from his typological work.

The main volume of Montelius’ research available in Chinese translation was Pre-historical Archaeological Methods (Xianshi kaoguxue fangfa lun 先史考古学方法论) originally published by the author himself in Sweden in 1903, in German, under the title Die Methode, as the first volume of his Die älteren Kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa. The second volume of this work, Babylonien, Elam, Assyrien (Montelius 1923), was in comparison ‘a specialized piece of research whose objectives were slightly different from the more general and integrative project of Die Methode’ (Montelius 1937 [‘Translator’s Foreword’]: 1).

Die Methode appears to have first caught the attention of Chinese scholars in the early 1930s when Zheng Shixu and Hu Zhaochun translated the work, under the title Archaeological Research Methods (Kaoguxue yanjiu fa 考古学研究法). Their translation was first published in serial form in Issues 2–6 of the first volume of the journal World of Learning (Xueshu shijie 学术世界) in 1935, and was then published in book form the next year (Montelius 1936) by the Shijie shuju (World Books Company). Independently, Teng Gu also prepared a Chinese translation of Die Methode in early 1935, which was published two years later by Shanghai’s Shangwu (Commercial) Press as Xianshi kaoguxue fangfa lun (Montelius 1937).

The extent of the influence of these translated works on Chinese archaeology at the time remains a topic in need of further investigation. Solely in terms of citations, their influence was not particularly evident.3 From a methodological perspective, a number of scholars believe that typological research work within Chinese archaeology was probably inspired by Montelius’ insights. For example, in the ‘Afterword’ to Selected Archaeological Writings of Su Bingqi, leading contemporary archaeologists Yu Weichao and Zhang Zhongpei observed that:

Stratigraphy and typology are the primary methodologies of modern archaeology. A systematic typological theory was first developed by Oscar Montelius in Die Methode, the first volume of his 1903 publication Die älteren Kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa. Two Chinese translations of this work were produced in the 1920s and 1930s; by the 1940s, Su Bingqi had made fundamental contributions to this methodology’s application and development through numerous studies which integrated novel archaeological materials and focused particularly upon China (Yu and Zhang 1984: 310).4

In the 1920s and 1930s, scientific archaeology was just beginning to emerge in China, and the ideals of the New Culture Movement, that included aspirations to draw on Western science, were gaining momentum. The fact that Montelius’ typological methodology was able to move beyond specialized archaeological journals, to be featured in World of Learning, and to be published in two separate book-length translations, suggests that his work was generating a substantial degree of interest in intellectual circles at the time.5

Before the discovery in the archives of the document, which is the focus of our paper, this was, more or less, the sum total of what we knew about Montelius’ influence on Chinese archaeology. Without this new archival discovery, we probably would never have known that Montelius, later in his life, had taken an interest in China, and indeed had great hopes for potential archaeological discoveries there. Additionally, we would never have known that it was probably the encouragement of Oscar Montelius that impelled Johan Gunnar Andersson’s (1874–1960) transformation from renowned geologist and paleontologist to a scholar of Chinese archaeology, who participated in numerous major and pioneering archaeological surveys, excavations, and other research projects in China during the 1920s, in his capacity as a member of China’s National Geological Survey (see Fiskesjö and Chen 2004; Chen 1997; Fiskesjö 2011).

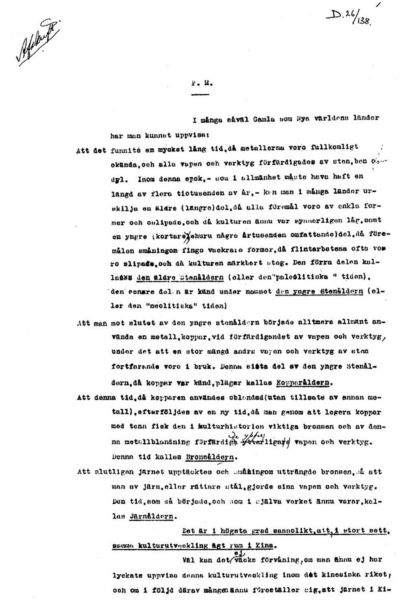

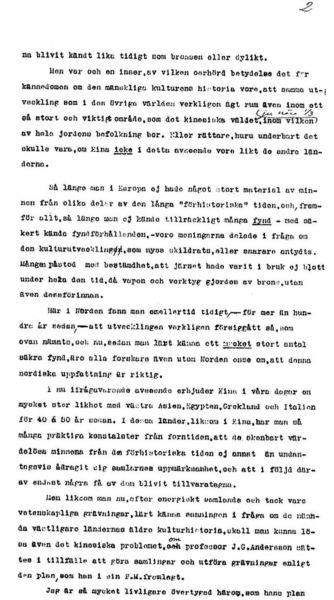

The following document is a pro memoria6 authored by Montelius (1920) in support of Andersson’s Swedish funding application for archaeological research in China. It was found by the authors of this paper in the archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm, in late September 2001, during Chen Xingcan’s visit to the museum. The original is in Swedish. It was first translated into English by Magnus Fiskesjö, and subsequently into Chinese by Chen Xingcan (Chen and Fiskesjö 2003). It is currently stored in the archives of Stockholm’s Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (File no. D26/138). It is reproduced in full below, followed by a revised English translation (with words underlined by Montelius as in the original Swedish text).

P.M. (Pro memoria)

In many countries of both the Old and the New World it has been possible to show:

That there once was a very long period, when metals were entirely unknown, and all weapons and tools were manufactured from stone, bone, and the like. Within the scope of this period – which generally must have had a length of several tens of thousands of years – one can discern an older (longer) part, when all artefacts were made in simple forms, and unpolished, and when culture was still very low, and then a more recent period (shorter, but several thousand years long) when artefacts were increasingly given more beautiful shapes, when work in flint was often polished, and when culture clearly advanced. The former period is called the older Stone Age (or the ‘Paleolithic’ period); the later part is known under the name of the younger Stone Age (or the ‘Neolithic’ period).

That towards the end of the younger stone age one metal, copper, was increasingly used in the manufacture of weapons and tools, all the while a great deal of other weapons and tools made from stone were still in use. This last part of the younger stone age, when copper was known, is usually called the Copper Age.

That this period, when copper was used unmixed (without the addition of another metal), was followed by a new period, in which the alloying of copper with tin yielded bronze, which has had such importance in cultural history, and in which this mix of metals was used to manufacture exquisite weapons and tools. This period is called the Bronze Age.

That finally iron was discovered, and ultimately displaced the bronze, so that people made their weapons and tools from iron or, properly, from steel. This period, which was begun at that point and in reality still continues, is called the Iron Age.

It is extremely likely that, in general terms, a similar development has occurred in China.

Surely it cannot be a cause of surprise that this cultural development has not been demonstrated within the country of China, and, if as a consequence of this, many people still imagine, that iron in China became known as early as bronze, or the like.

But everyone realizes what outstanding importance it would have for the knowledge of the history of human culture if the same development as that seen in the rest of the world had indeed taken place within such a large and important area as that of the Chinese realm, within which close to one third of all of earth’s population is living. Or more correctly, how wonderful it would be, if China was not in this respect like the other countries.

As long as there was not, in Europe, a large accumulated material of memories from different parts of the long ‘prehistoric’ period, and, above all, as long as not enough finds were known – along with secure knowledge of the circumstances of the finds – opinions were divided with regard to the cultural development that has just been sketched, or rather, hinted at. Many firmly held that iron had been in use not only all the way through the time when weapons and tools were made from bronze, but also before that time.

Here in the Nordic countries it was discovered early on – more than a hundred years ago – that the development really had taken place in the way that has been described here, and now, after becoming familiar with a very large number of secure finds, all scholars, including those outside of the Nordic countries, are unanimous in the view that this Nordic position is correct.

In this present respect, China in our day offers a very great similarity to Western Asia, Egypt, Greece, and Italy of 40 to 50 years ago. In these countries, just as in China, there are so many awesome art works left from antiquity, that the seemingly worthless memories of prehistoric times have attracted the attention of the collectors only occasionally, and as a result of this, only few of them have been preserved.

But just as today, after energetic collection, and thanks to scientific excavations, the truth has become known about the above-mentioned Western countries’ early cultural history, the Chinese problem may be solved, too, if Professor J. G. Andersson is put in the position of making collections and undertaking excavations according to the plan which he has put forward in his pro memoria.

I am convinced of this even more, because his plan seems to me very well considered, and the project would have as a leader a scientist of Professor Andersson’s high rank.

Few words are needed to convince us here in Sweden for us to realize of what great importance it would have for our small people if Swedish scientists were to be recognized for spreading light over the oldest history of the ancient cultural country of China, and if those Swedish scientists’ work were to have been made possible by powerful support from other open-minded Swedish men.

(In handwriting:) Stockholm, on the 31st of May, 1920.

(Signature:) Oscar Montelius.

Regardless of whether the document in the archives is an original or a copy, evidence ensures that this pro memoria was indeed written by Oscar Montelius and sent to Johan Gunnar Andersson. First, the document features Montelius’ signature. Second, another letter which Andersson (no date) later addressed to an unidentified Chinese scholar by the name of Chang clearly drew on this same document.

For the sake of comparison, this letter is also featured below:

D.26/138

Dear Mr. Chang,

Professor Oscar Montelius, the famous Swedish archaeologist, has sent me a short note on the different prehistoric ages and the early use of metals in Europe. His communication is in Swedish but as it may prove of some interest for your present researches, I have the pleasure of herewith to forward you a translation of it:

‘In the Old as well as in the New World the following facts have been well established:

1. There was, in the early history of mankind, a very long time when the metals were entirely unknown, and all arms and tools were made of stone, bone, or other materials ready at hand. Within this epoch (that in most parts of the world evidently had a length for several tens of thousands of years), it has been established in several countries an earlier longer period, when all implements were very simple in shape and unpolished and the whole culture was still very primitive, and a later shorter period (duration some few thousand years), when the implements gradually obtained more beautiful shape, when the flint implements were often polished and the culture underwent noticeable successive progress. The former period is called the Old (Paleolithic) Stone Age, the latter the Young (Neolithic) Stone Age.

2. Towards the end of the Young Stone Age, a metal, copper, became commonly used for the manufacturing of arms and tools but at the same time a great number of stone implements were still in use. This latest part of the Young Stone Age, when copper was already known, has been called the Copper Age.

3. This period, when copper alone was used without any admixture, was followed by a new time, when the metal tools became highly improved by alloying the copper with tin. This alloy, bronze, has played a rather unparalleled role in the history of man, and arms and tools of excellent shape date from this period, the Bronze Age.

4. Finally iron was discovered and gradually displaced the bronze. The arms and tools were made of iron or more properly [of] steel. This period which extends to the present day has been called the Iron Age.

It is very likely that China also experienced a similar course of cultural development.’

In another letter, Professor Montelius furthermore provided a few pieces of more detailed data which you may find interesting:

‘In the pre-classical era in central Italy, we can divide the bronze age and iron age respectively into five and six successive periods, the last of which came to an end before 500 [BCE]. The iron age’s first period was a time of transition from bronze implements to iron implements, with weapons and tools made from both bronze and iron coexisting. In the second period, a substantial number of bronze items remained, but iron had already become the primary material. During the third period, bronze items became increasingly scarce, and by the time of its conclusion, bronze implements had completely disappeared.

The first period of the iron age in central Italy began around 1100 [BCE], and its third period concluded in 800 [BCE]: within just 300 years of the appearance of iron implements, bronze ware had completely faded out of use.

A similar pattern can be seen in Sweden and other Germanic countries. Following the introduction of iron, bronze implements continued to be used in varying degrees for a few centuries before disappearing.’

I hope that you will find this all to be of interest.

Yours truly

The ideas expressed in the first half of this unsigned copy of a letter to a certain Mr. Chang obviously came from Montelius’ pro memoria, which Andersson refers to as ‘a short note’. The second half, as Andersson acknowledges, is quoted from another letter, as Montelius’ pro memoria made no mention of the chronology of the Bronze Age in Europe. However, we have yet to find any such letter from Montelius in Andersson’s archives, nor any related letters from Andersson to Montelius.

The above letter is also included in File no. D26/138. The original letter is undated and written in English. Its final lines are handwritten by Andersson: however, perhaps because the document on file is a copy, or even more likely a rough draft, it is not signed, and there are multiple revisions marked throughout the text. As the letter was clearly written after Montelius’ pro memoria of May 31, 1920, but was also placed within the same file, it was likely written sometime in the second half of 1920. The letter’s employment of terminology suggests that it was addressed to a fellow expert in related fields. The Mr. Chang to whom it is addressed is most probably the geologist H. T. Chang (Hongzhao Zhang, sometimes written H. C. Chang), although there may have been other archaeologists or historians by the same last name.

H. T. Chang was a Japanese-trained geologist, who worked in China in the early twentieth century, and who had frequent contact with J. G. Andersson during his time in Beijing. While there is no direct evidence to prove conclusively that Andersson’s letter was addressed to this H. T. Chang, Andersson mentioned Chang in many of his own writings, and H. T. Chang himself presented a detailed exposition of the Three-Age System and of Andersson’s archaeological discoveries in his own work (see H. T. Chang [Hongzhao Zhang] 1923, 1927; also cited in Needham and Wang 1959; and by Andersson 1923a: 44 and 1923b: 44; see also Andersson 1921, 1929).7

Andersson’s decision to seek advice from Oscar Montelius, prior to Montelius’ death, is an established historical fact. However, we now know that Andersson had also previously sought assistance from Montelius in his search for research materials. This is evident in a letter written in English to his longstanding Swedish supporter and financier Axel Lagrelius on February 2, 1922 (Andersson 1922a). Lagrelius was a central figure in the China Research Committee (also known as the China Committee, and, in Swedish, Kinakommittén, or Kinafonden), and a renowned Swedish entrepreneur who, on account of his position as a Marshal of the Royal Court, had a particularly close relationship with Swedish royalty and accompanied the Swedish Crown Prince on his visit to China in 1926 (on these events, and Andersson’s letter to the Swedish Crown Prince see Fiskesjö and Chen 2003: 10–17; see also Lewenhaupt 1928; Johansson 2009, 2012).

The China Research Committee was founded by Lagrelius on September 15, 1919, and original members comprised Lagrelius, Admiral Palander, and a renowned economic geographer by the name of Gunnar Andersson (no relation to Johan Gunnar Andersson). Its primary and original objective was to support Andersson’s work collecting geological and paleontological samples in China (see Andersson 1929; Almgren et al. 1932).8

In the 1922 letter, Andersson sought Lagrelius’ help in purchasing books: noting that Ture J. Arne9 had previously sent him archaeology books, and he hoped that others might make similar contributions by sending books that were readily available in Sweden. If he was able to collect such donations, he said, he could donate these books to China’s National Geological Survey or to a Chinese university. On February 17, 1922, he wrote another letter to Lagrelius (Andersson 1922b) noting that a list of desirable books had already been sent to T. J. Arne, adding that Oscar Montelius’ books had been donated to the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities (Vitterhetsakademien) but there would still be extra copies that he could send Andersson. Throughout his time in China, Andersson frequently sought books and other materials in the fields archaeology and paleontology: his contacts in this search included the American Museum of Natural History, German archaeologist Hubert Schmidt,10 T. J. Arne, Lagrelius, and many others.11 Yet it remains unknown whether this letter from Montelius, cited by Andersson, was in fact the same letter in which Montelius introduced his periodization of European archaeology, as these letters have yet to be discovered. We also do not know whether Montelius’ extra books were ever sent to Beijing. Despite these uncertainties, this correspondence is further direct evidence indicating Montelius’ influence on Chinese archaeology during his lifetime.

Montelius and Andersson’s Archaeological Discoveries

We can now proceed to ask what aspects of Chinese archaeology captured Oscar Montelius’ interest, and why; and what direct influence did his initiative exert upon Chinese archaeology? With the discovery of Montelius’ pro memoria, we can now at least be certain that the Stone Age and its artefacts had come to Andersson’s attention prior to his discovery, in 1921, of Yangshao culture, as Andersson himself indeed alludes to in his own publications (Andersson 1920, 1973).12 Due to the limitations of his prior archaeological knowledge and training, and given the link between Montelius and the Crown Prince (who was a significant supporter of Andersson’s work, and who was tutored in archaeology by Montelius) it is highly likely that Andersson sought the advice of Oscar Montelius, and hoped that Montelius’ support would help to ensure support and funding for archaeological work in China. It is also probable that Montelius’ support did indeed play a central role in mobilizing Swedish financial support for Andersson, and helped to propel new research as such. Indeed, Andersson’s archaeological research plan appears to have first taken shape around the time of Chinese New Year in 1920. His previous plans for paleontological collecting in China, such as one major outline dated August 1, 1918,13 make no mention of archaeological work. Then, based upon his and his Chinese colleagues’ discovery of Stone Age stone implements in February 1920, Andersson published ‘Stone Implements of Neolithic Type in China’ (Andersson 1920), signaling an enhanced interest on Andersson’s part in delving into Neolithic archaeology, a subject dramatically different from the paleontology and geology investigations which he had pursued since arriving in China in 1914 on the invitation of the new National Geological Survey. In the winter of 1920, Andersson first discovered stone implements in the village of Yangshao, and in the following year, he participated in two formal excavations at Yangshao village in Henan Province and Shaguotun Township in Jinxi County, Liaoning Province – these events officially marked his transition to archaeology (see Chen 1997; see also Fiskesjö and Chen 2004).

Even following this major transition in 1921, Andersson still had a special place in his heart for paleontology. However, his plans to continue to pursue the collecting of vertebrate fossils in Kansu (Gansu) in 1923 failed to occur, and in the meantime, he had discovered dozens of cultural heritage sites related to the previously unknown prehistoric Yangshao culture. Of this time Andersson said: ‘In fact that summer’s work in Kansu was the turning point in my life, and definitely diverted my interest from geology and paleontology to the study of prehistoric remains’ (Andersson 1929: 22–23). In the same text he also recalled that: ‘during the early years of my collecting campaign, 1918–1920, my interest was centered upon fossil mammals, whereas from 1921 to the end of my travelling period in 1924, my interest and energy was increasingly absorbed by archaeology’ (Andersson 1929: 24).14

Andersson always remained a scientist with particularly broad interests, who was without fail fascinated by any fossils, or cultural relics related to humankind as a whole. This passion was the decisive factor in many of his discoveries (Karlgren 1961; Mateer and Lucas 1985), such as that of quartz deposits in Zhoukoudian, and it was Andersson’s identification of the potential of this site for paleoanthropological discoveries, which later led to the discovery of ‘Peking Man’. In particular, the breakthrough discovery of the previously unknown prehistoric cultures at Yangshao and elsewhere carried profound significance for modern China.

In addition to Andersson’s own personal research interests and passions, it was probably Montelius’ enthusiastic assessment of the potential value and prospects of archaeological work in China that was another key factor in his shift in careers. Montelius’ glowing comments likely strengthened the determination of this world-renowned geologist and paleontologist to make the transition to archaeology. One can easily imagine the impact of Montelius’ pro memoria, in which China’s archaeological potential, described at the time as virgin territory for archaeologists, is compared to that of Western Asia, Egypt, and Italy of four or five decades earlier. Montelius was indicating that with just a little effort, the most astounding of archaeological results could be attained. Such predictions, particularly coming from such a pre-eminent archaeologist, were certain to boost Andersson’s confidence and reaffirm his resolve to pursue archaeology.

Moreover, the Three-Age System, used to describe the development of humanity’s material culture, comprising Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages, was first applied scientifically to archaeological remains in Scandinavia,15 and had subsequently been confirmed in studies throughout Europe and surrounding areas. Nevertheless, at the time of Montelius’ pro memoria, the Three-Age System had yet to be put to the test in China, where modern archaeology had barely been introduced, and where the conception of the past was still largely organized in terms of imperial dynasties and pre-imperial cultural heroes as recorded in Classical Chinese texts (cf. Fiskesjö and Chen 2012).

Montelius thus noted (in his pro memoria) that tracing the development of material civilization in the ‘large and important area … of the Chinese realm, within which close to one third of all of earth’s population is living’ was of the utmost importance for ‘the knowledge of human cultural history’. Such comments demonstrate Oscar Montelius’ boundless passion for understanding the process of human cultural development as a whole, as well as his extraordinary foresight and vision in the field of archaeology. While this letter itself was not responsible for introducing the seriation of human material culture into China (cf. Yu 1983), Montelius’ affirmation of the potential significance of re-discovering the Three-Age System in China nevertheless had an extraordinary impact on the subsequent development of Chinese archaeology.

Despite the brevity of his comments, Montelius unambiguously emphasized the importance of China’s ancient civilization, as well as the immense value of researching and discovering this ancient civilization for the ‘small people’ of Sweden. This comment shows considerable foresight, for the contributions of Swedish scholars in the early history of Chinese archaeology were indeed unmatched. As these contributions began with J. G. Andersson, they are in many respects derived from the open-minded vision of Montelius himself (Fiskesjö and Chen 2003; Lewenhaupt 1928; Johansson 2009, 2012; Mateer and Lucas 1985; and Fiskesjö 2011).16

Montelius did not have any personal scholarly investment in confirming the Three-Age System in China. As he said in his pro memoria: ‘surely it cannot be a surprise that this cultural development has not been demonstrated within the country of China, and, if as a consequence of this, many people still imagine, that iron in China became known as early as bronze, or the like’. Upon examination, it turned out that iron did not appear contemporaneously with bronze in China: nevertheless, it did become apparent that the Bronze Ages of China and Europe were completely different phenomena. The representative artefacts of each, sacrificial vessels in China, and weapons and tools in Europe, stand in stark contrast to one another, reflecting the divergent types of civilization that emerged in the East and the West. Since then archaeology has greatly contributed to the understanding of these differences (see Chang 1999; Fiskesjö 2003; Sherratt 2006).

Based on his correspondence with Andersson, it seems that Montelius’ theories about the Three-Age System of material culture, and his seriation of European cultures, may have been unacknowledged influences on Andersson’s periodization of prehistoric cultures in China and his corresponding division of ages. This is particularly notable in Andersson’s six-age theory of cultural development in Kansu, which classified the pre-historical cultures of the region into neat and uniform periods of exactly three hundred years (Andersson 1925; 1973: 211).17 This structure bears a clear mark of inspiration derived from Montelius’ periodization of European culture.

Of course, Montelius’ primary influence on Andersson was probably through his publications, rather than through their private correspondence alone. Oscar Montelius passed away in 1921, and ten years later, in his most famous and popular work on his Chinese discoveries, The Children of the Yellow Earth, Andersson (1973: 211) once again cited Montelius, as follows:

Among the Chinese socketed bronze celts (…), there is one type which bears such a striking resemblance to the modern iron ‘pen’ (…) that there can be no doubt that they have a common origin. The resemblance is complete, except that with the bronze celt is more slender and more elongated, which was probably due to the fact that it was not an agricultural implement but rather a weapon or a votive object.

Montelius has among his typological series described the complicated but unbroken sequence of evolutionary steps between the simple Neolithic stone celt and the gracefully shape and richly decorated axes of the Bronze age.

We do not yet possess such a complete typological series for China, but I think that I am justified in drawing attention to a type of stone celt (…), which, to judge by its form, may possibly be the prototype of the Chinese socketed celts (Andersson 1973: 211).

We note that Andersson, in his famous publication where he introduced the breakthrough discovery of a Neolithic era in China, ‘An Early Chinese Culture’ (Andersson 1923a, 1923b), presented a detailed analysis of whether the Yangshao Culture, first discovered in Honan (Henan) Province, was indeed a Neolithic culture. Although Andersson makes no mention of Montelius’ pro memoria, he cited:

‘a powerful impetus to follow up the initial discoveries … the decision by the Directors of the National Geological Survey Dr. V. K. Ting and Dr. W. H. Wong that amongst the existing scientific institutions of the Chinese government, the Geological Survey is best prepared to carry on these field researches in strictly topographic and stratigraphic manner’.

But Montelius’ influence is quite apparent in Andersson’s differentiation of the Stone Age and Bronze Age. Of course, the Three-Age System of human material culture had already become common knowledge throughout Scandinavian academia at the time, and Andersson’s approach probably derived from both Montelius’ published works, and his correspondence with him. In any case, Andersson writes that:

The famous explorer of the chronology of the Bronze Age, Oscar Montelius, whose death science has recently had to deplore, has, in his fundamental work on the typological method, given an admirable exposé of the intricate but unbroken European series of transitions from the simple stone celt of Neolithic times to the graceful and richly decorated metal celt of the Bronze Age (Andersson 1923a: 6).

Andersson noted that ‘no such series is so far known from China’, but gave detailed consideration to the new breakthrough discoveries and all the comparable implements, including those still preserved by everyday use in the same regions of North China, in his time. He recalled the tentative opinions previously formed by Chinese and foreign scholars, such as Berthold Laufer and Ryuzo Torii, regarding the existence of a Chinese ‘Stone Age’ in what is now China (Andersson 1923a: 11–12), ahead of the Yangshao discoveries that now unquestionably established the existence of such a period – just as Montelius had predicted.

However, Andersson left open the question of the day: that is, whether it was the forebears of the Chinese, or some form of ‘barbarians’ who had created these previously unknown industries and artefacts (but he leant heavily in favour of a Chinese connection). He answered the question of the ‘age’ of the Yangshao remains with a detailed discussion that included the following reference to an intervention by Yuan Fuli, the Chinese geologist assigned to the project by the National Geological Survey:

… In its general composition the Yang Shao site gives the impression of a complete late Neolithic culture. If we compare the material which we obtained from the Honan site with the collections from the famous Neolithic stations in Europe, we will find that all the essential elements of the latter are present in the Honan site, viz: stone axes, adzes, and knives, stone and bone arrow points for the men, the hunters and fighters, stone armelets serving as adornment for the women and neat little needles for their hand-work.

A people which had ready access to metal would never had taken the trouble to shape all these tools of inferior material. During our five weeks of extensive and careful excavations we never met with a single metal object in situ. On one of our last days at this site a mischievous village-boy pretended to have found a bronze arrow point at one of our excavation places, and I was inclined to accept his statement with some reservation. But Mr. Yuan went into the matter with more determination and soon found out that the arrow point had been brought from a place N. of Yang Shao Tsun, probably from some Han tomb, and that the little fraud had been attempted in the hope of gaining a few more coppers for the metal object by saying that it had come from our beloved ‘ashy earth,’ the characteristic soil of the culture stratum (Andersson 1923a, 1923b: 28–29).

Oscar Montelius and his work clearly left a deep impression on Johan Gunnar Andersson18. As noted above, up until now this influence was only noted as traces of Montelius’ methodological insights in Andersson’s scholarly work. However, the pro memoria featured in this paper (and perhaps the still undiscovered correspondence between Montelius and Andersson) clearly demonstrates:

- Montelius’ essential role in Andersson’s transition from geology to archaeology, as well as

- Montelius’ interest in Chinese archaeology and his direct influence on its early development.

As such, these documents are priceless references in the history and development of Chinese archaeology, and are thus worthy of our close attention.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Specifically: Age I, 1800–1500 BCE; Age II, 1500–1300 BCE; Age III, 1300–1100 BCE; Age IV, 1100–900 BCE; Age V, 900–600 BCE; and Age VI, 600–500 BCE. (Based upon notes taken by Chen Xingcan during a visit to the exhibition on September 25, 2001).

- The most comprehensive biography to date (in Swedish) is by Evert Baudou (2012), a book that is, however, silent on the issue of Montelius’ influence beyond Europe.

- On the influence of Montelius’ ideas on prominent early Chinese archaeologists, see for example: Zhang Guangzhi and Li Guangmo 1990 on Li Ji (also Li Ji 1990), often described as the ‘father’ of Chinese archaeology; also see Su Bingqi 1984. On the emerging awareness in wider intellectual circles of this methodology, also see Teng Gu’s ‘Translator’s Foreword’ and ‘Translator’s Introductory Remarks’ in Montelius 1937.

- See Note 3, above. Chen 1997 also noted that the translation of Montelius’ Die Methode ‘provided a theoretical and methodological model for Chinese archaeologists’.

- On the general historical background and the specifics of the beginnings of Chinese archaeology in the 1920s, see Fiskesjö and Chen 2004; for further discussions see Chen 1997; and Fiskesjö 2011.

- Pro memoria: In the Swedish context, this refers to a memo, or circular, of considerable significance.

- The ‘BCE’ annotations included in the text were added by the authors.

- At the time of the founding of the China Research Committee, Admiral Palander was its president and Gunnar Andersson its committee secretary. When Palander died in 1921, Sweden’s H. R. H. Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf took over as president. When Gunnar Andersson died in 1928, Bernhard Karlgren, the renowned Sinologist and professor at the University of Gothenburg [Göteborg] (and, from 1938, Andersson’s successor as Director of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities) took over as secretary. On the history of this committee in relation to the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities see Fiskesjö forthcoming [2014]; see also Note 13 below.

- Ture Arne was a Swedish archaeologist later entrusted by Andersson to research excavated materials from Henan, China, see Arne 1925; for more information refer to the sources cited in Note 5.

- 10Schmidt discovered the archaeological site of Anau, and was cited by Andersson in his pioneering piece ‘An Early Chinese Culture’ (Andersson 1923a, 1923b: 39–40); and in later publications (notably Andersson 1943) where he reflected on the similarities of prehistoric ceramics from Central Asia and that which he himself had discovered in China (see Fiskesjö and Chen 2004).

- Observations based on files stored in the archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Also see Andersson 1921: 4–12 in which Andersson notes that ‘the greatest difficulty for scientific work within the survey has been the lack of literature’. As a result, one of the survey’s primary missions was a constant search for contributions and donated materials from both public and private donors.

- A detailed chronological bibliography of all of Andersson’s work is available, at no cost, in draft form from Magnus Fiskesjö: magnus.fiskesjo@cornell.edu.

- ‘General Plan for Natural Collections in China by Means of China Funds [Kina-Fonden]’, in the Archive of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm (Kinakommittén [China Research Committee] section in Volume 3, ‘Kinakommitténs korrespondens rörande Johan Gunnar Anderssons samlingsarbete i Kina 1918–1935’; and Volume 4, ‘Kinakommittén korrespondens rörande Johan Gunnar Anderssons samlingsarbete i Kina 1919–1928’). Andersson’s research in China was primarily funded by the China Research Committee, and several parts of the archives include substantial amounts of related correspondence, including research reports, budgets, and various other items.

- Andersson went to China as an accomplished and prominent geologist and paleontologist, but because of his discoveries he returned to Sweden as an archaeologist, and he very much remained so, until his death. Besides the museum directorship he was also formally appointed to a personal professorship in East Asian archaeology at Stockholm University. This apparently caused some consternation among his geologist colleagues, who felt they had ‘lost’ him; on the other hand, the fine-arts collectors surrounding the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities later took to, once again, labeling him a geologist, evidently to diminish his role in the museum’s foundation and in the first chapters of its history. On these aspects of Andersson’s later career, including how he came to be largely forgotten in post-World War II Swedish archaeology, see the sources cited in Note 5 above; also Fiskesjö forthcoming [2014].

- Speculation that humankind had passed through such stages was known both from Western antiquity (as in De Rerum Natura by Titus Lucretius Carus, ca. 99–55 BC), and from ancient China (Yuan Kang’s quoting of Feng Huzi in Yuan’s Yue jue shu 越绝书 also from the 1st century AD – ages that also included jade, in addition to stone, bronze and iron). In Europe, of course, the Three-Age System was introduced into archaeology by the Danish scholar Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788–1865), who used it first, to reorganize museum collections; and by his compatriot Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae (1821–1885) who operationalized it as stratigraphy in modern field archaeology (cf. Ole Klindt-Jensen 1975); it was then applied more widely by Montelius and others.

- Andersson was, generally speaking, a scholar who kept his distance from nationalist sentiments. Nevertheless, one can still detect within his letters his personal investment in Swedish research on China and his complex and conflicted attitude towards America and other Western countries’ competitive collecting in China. Perhaps such sentiments made Montelius’ comment on the significance of researching the ancient civilization of China for the ‘small people’ of Sweden have an even more powerful effect on Andersson. See Andersson’s letter to the Crown Prince of Sweden, with commentary, September 4, 1921, in Fiskesjö and Chen 2003.

- For a comparative discussion of Andersson’s manuscript Archaeological Discoveries in Kansu and the published version of Preliminary Report on Archaeological Research in Kansu, see Chen and Fiskesjö 2004.

- For Andersson’s final analysis summing up his archaeological research, see Andersson 1943; and for discussion see Fiskesjö and Chen 2004.

References

- Andersson, J G (No date). Letter to Mr Chang In: File no. D26/138. Stockholm: Archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. (probably 1920).

- Andersson, J G (1922a). Letter to Axel Lagrelius. Stockholm: Archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. February 2 1922a

- Andersson, J G (1922b). Letter to Axel Lagrelius. Stockholm: Archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. February 17 1922b

- Kinakommittén (China Research Committee). ‘General Plan for Natural Collections in China by Means of China Funds (Kina-Fonden)’. Stockholm: Archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. (Kinakommittén [China Research Committee] section, in Volume 3, ‘Kinakommitténs korrespondens rörande Johan Gunnar Anderssons samlingsarbete i Kina 1918–1935’; duplicate in Volume 4, ‘Kinakommitténs korrespondens rörande Johan Gunnar Anderssons samlingsarbete i Kina 1919–1928’).

- Montelius, O (1920). Pro memoria In: File no. D26/138. Stockholm: Archives of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. May 31 1920

- Almgren, O et al. (1932). Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf as a Promoter of Archaeological Research. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 4: 1–3.

- Andersson, J G (1920). Stone Implements of Neolithic Type in China In: The China Medical Journal (Zhonghua yixue zazhi). Medical Missionary Association of China, Anatomical Supplement, July 1920p. 7.

- Andersson, J G (1921). The National Geological Survey of China. Natural History 21(1): 4–21.

- Andersson, J G (1923a). An Early Chinese Culture. Bilingual: English-Chinese. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China 5: 1–68.

- Andersson, J G (1923b). An Early Chinese Culture. Peking: Geological Survey of China.

- Andersson, J G (1925). Preliminary Report on Archaeological Research in Kansu. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of China Series A (5)

- Andersson, J G (1929). The Origin and Aims of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 1: 11–27.

- Andersson, J G (1943). Researches into the Prehistory of the Chinese. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 15: 7–304. plus 200 plates.

- Andersson, J G (1973). The Children of the Yellow Earth: Studies in Prehistoric China. Cambridge: MIT Press. (First translated in 1936 from Den gula jordens barn: studier över det förhistoriska Kina. Stockholm: Bonniers, 1932).

- Arne, T J (1925). Painted Stone Age Pottery from the Province of Honan, China. Paleontologica Sinica, New Series D,

- Åström, P ed. (1995). Oscar Montelius, 150 Years. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell International.

- Baudou, E (2012). Oscar Montelius: Om tidens återkomst och kulturens vandringar (Oscar Montelius: On the Return of Time and the Wanderings of Culture). Stockholm: Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities & Atlantis.

- Chang, H T [Zhang Hongzhao 章鸿钊] . (1923). Shi ya 石雅 (Lapidarium sinicum: A Study of the Rocks, Fossils and Minerals as Known to Chinese Literature). Bulletin of the Geological Survey of China 2(2)

- Chang, H T [Zhang Hongzhao 章鸿钊] . (1927). Shi ya 石雅 (Lapidarium sinicum: A Study of the Rocks, Fossils and Minerals as Known to Chinese Literature). Beiping: National Geological Survey of China. 2nd ed.

- Chang, Kwang-Chi [Zhang Guangzhi] . (1999). Zhongguo qingtong shidai (The Chinese Bronze Age). Beijing: Sanlian.

- Chen, Xingcan . (1997). Zhongguo shiqian kaoguxue shi yanjiu, 1895–1949 (History of Chinese Prehistoric Archaeology, 1895–1949). Beijing: Sanlian.

- Chen, Xingcan; Fiskesjö, M . (2003). Mengdeliusi yu Zhongguo kaoguxue (Oscar Montelius and Chinese archaeology) In: Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 21 shiji Zhongguo kaoguxue yu shijie kaoguxue (Chinese Archaeology and World Archaeology in the 20th Century). Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, pp. 686–695.

- Chen, Xingcan; Fiskesjö, M . (2004). Gansu kaogu faxian yu Gansu kaogu ji: Yige xueshu shi de wenti In: bianjiang kaogu yanjiu zhongxin, Jilin daxue (ed.), Qingzhu Zhang Zhongpei xiansheng qishi sui lunwen ji. Beijing: Kexue Press, pp. 63–73.

- Daniel, G (1981). A Short History of Archaeology. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Fiskesjö, M ed. (2003). New Perspectives in Eurasian Archaeology. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 75 Special Issue.

- Fiskesjö, M (2011). Science Across Borders: Johan Gunnar Andersson and Ding Wenjiang In: Glover, D. M., Harrell, S., McKhann, C. and Swain, M. eds. Explorers and Scientists in China’s Borderlands, 1880–1950. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 240–266.

- Fiskesjö, M (forthcoming [2014]). Art and Science as Competing Values in the Formation of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities In: Lai, Guolong, Steuber, J. J. (eds.), Collectors, Collections, and Collecting the Arts of China: Histories and Challenges. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

- Fiskesjö, M and Chen, Xingcan (2003). Zhongguo jindai kexue shi shang de zhongyao wenxian – Antesheng zhi Ruidian Huangtaizi de xinji jiqi jieshi (An important document for the history of modern Chinese science: Andersson’s letter to the Swedish Crown Prince, with commentary). Gujin lunheng (Disquisitions on the Past and Present) 8: 10–17.

- Fiskesjö, M and Chen, Xingcan (2004). China Before China: Johan Gunnar Andersson, Ding Wenjiang, and the Discovery of China’s Prehistory (a completely bilingual English-Chinese volume). Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Fiskesjö, M and Chen, Xingcan (2012). China: Politics and Archaeology In: Oxford Companion to Archaelogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd ed. 1pp. 312–316. ACHE–HOHO.

- Johansson, P (2009). Rescuing History From the Nation: The Untold Origins of the Stockholm Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Journal of the History of Collections 21(1): 111–123, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhn030

- Johansson, P (2012). Saluting the Yellow Emperor: A Case of Swedish Sinography. Leiden: Brill, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004226395

- Karlgren, B (1961). Johan Gunnar Andersson In Memoriam. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 33: i–iv. eight plates.

- Klindt-Jensen, O (1975). A History of Scandinavian Archaeology. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Lewenhaupt, S (1928). Axel Lagrelius’ Kina-resa av honom själv berättad (The China Journey of Axel Lagrelius, as Told by Himself). Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Li, Ji [Li Chi] . (1990). Guangzhi, Zhang, Guangmo, Li Li (eds.), Li Ji kaoguxue lunwen xuanji (Selected Archaeological Writings of Li Chi). Beijing: Wenwu [Cultural Relics Press].

- Mateer, N J and Lucas, S G (1985). Swedish Vertebrate Paleontology in China: A History of the Lagrelius Collection. Bulletin of the Geological Institutions of the University of Uppsala, New Series 11: 1–24.

- Montelius, O (1903). Älteren kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa. Part I. Die Methode. Stockholm: Published by the author.

- Montelius, O (1923). Älteren kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa In: Lindquist, Sune (ed.), Part II. Babylonien. Elam. Assyrien. Stockholm: Published by the author.

- Montelius, O (1936). Shixu, Zheng, Zhaochun, Hu (trans.), Kaoguxue yanjiufa (Archaeological Research Methods). Shanghai: Shijie shuju. Translation into Chinese of Montelius 1903.

- Montelius, O (1937). Gu, Teng (trans.), Xianshi kaoguxue fangfa lun (Prehistorical Archaeological Methods). Shanghai: Commercial Press. Translation into Chinese.

- Needham, J and Wang, Ling (1959). Science and Civilization in China In: Mathematics and the Science of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 3

- Sherratt, A (2006). The Trans-Eurasian Exchange: The Prehistory of Chinese Relations with the West In: Mair, V. H. ed. Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 30–61.

- Su, Bingqi . (1984). Su Bingqi kaoguxue lunshu xuanji (Selected Archaeological Writings of Su Bingqi). Beijing: Wenwu [Cultural Relics Press].

- Yu, Danchu . (1983). Ershi shiji Xifang jindai kaoguxue sixiang zai Zhongguo de jieshao yu yingxiang (Western Archaeological Thought’s Introduction and Influence in China in the first half of the 20th Century. Kaogu yu wenwu (Archaeology and Cultural Relics) (4): 107–111.

- Yu, Weichao; Zhang, Zongpei . (1984). Afterword In: Su, Bingqi (ed.), Su Bingqi kaoguxue lunshu xuanji (Selected Archaeological Writings of Su Bingqi). Beijing: Wenwu [Cultural Relics Press], pp. 306–338.

- Zhang, Guangzhi, Li, Guangmo Guangmo (eds.), . (1990). Li Ji kaoguxue lunwen xuanji (Selected Archaeological Writings of Li Chi). Beijing: Wenwu [Cultural Relics Press].

Originally published by the Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 24 (2014), DOI:http://doi.org/10.5334/bha.2410, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.