The history of the OVRA reveals how the Fascist state harnessed surveillance and bureaucracy to manage political life and suppress dissent.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The creation of the OVRA, the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti Fascism, marked one of the most consequential transformations in the political life of interwar Italy. Conceived not as a continuation of the early Fascist squadristi but as a modern, centrally directed political police, the OVRA became the hidden infrastructure through which Benito Mussolini reshaped the Italian state into a system governed by surveillance, coercion, and ideological conformity. Its emergence reflected a broader European trend in which authoritarian regimes developed bureaucratic instruments designed to monitor dissent, discipline society, and convert political opposition into a matter of state security.1 The OVRA’s significance rests not only in the arrests it carried out or the dossiers it compiled but in the atmosphere of intimidation it generated, an atmosphere that helped normalize Fascist authority and diminish the possibilities of public challenge.

The rise of the OVRA cannot be understood without accounting for the political crisis that followed the murder of Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti in 1924 and the subsequent dismantling of parliamentary institutions. As Mussolini consolidated power, the regime sought more reliable tools for identifying internal enemies and preventing organized resistance, tasks that earlier paramilitary violence could no longer fulfill. The appointment of Arturo Bocchini as chief of police provided the regime with a technocrat capable of building a political intelligence structure that would reach into nearly every aspect of civic life.2 The OVRA emerged from this institutional redesign as a system whose authority stemmed not from public theater but from bureaucratic continuity, administrative discretion, and the cultivation of fear among ordinary Italians.

At the same time, the OVRA’s methods reflected the pragmatic and often improvisational character of Italian Fascism. Surveillance practices combined modern techniques of record keeping with older traditions of local informants, personal denunciations, and municipal policing.3 The result was a hybrid model of state repression that blurred the line between formal legality and extralegal coercion. Within this environment, citizens learned to navigate the risk of observation, censor their own speech, and avoid associations that might attract official suspicion. The OVRA thus shaped the psychological landscape of Fascist Italy by persuading the population that the state’s gaze was constant, even when direct intervention was infrequent.

Understanding the OVRA is essential for interpreting the mechanisms through which Mussolini maintained authority and presented his dictatorship as orderly, disciplined, and modern. Its activities reveal how surveillance became an ordinary feature of daily existence and how the Fascist state fused police power with ideological ambition. By situating the OVRA within both the institutional history of Italian Fascism and the comparative study of modern political policing, what follows examines the organization as a central instrument of repression and a key component of the regime’s attempt to reorganize Italian society. Its influence persisted far beyond the dictatorship’s fall, leaving documentary traces that continue to shape historical memory and scholarly interpretations of authoritarian rule in twentieth century Europe.

The Origins of Fascist Repression and the Creation of the OVRA

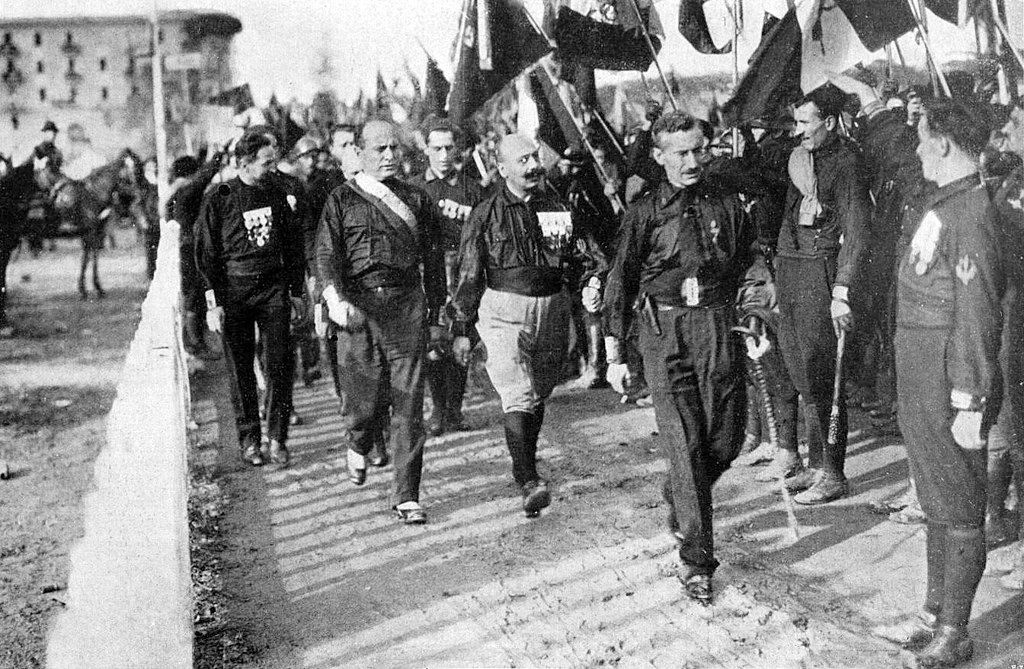

The emergence of the OVRA must be understood against the background of the regime’s initial reliance on extralegal violence and local intimidation. Early Fascist power depended on the squadristi, whose assaults on municipal officials, labor organizers, and opposition newspapers created a climate of disorder that weakened liberal institutions.4 Once Mussolini entered government in 1922, however, this irregular violence proved politically risky and administratively inconsistent. The state required a more disciplined system for monitoring dissent, and the transition from localized aggression to centralized political policing began as part of Mussolini’s broader attempt to institutionalize Fascist authority. The OVRA would eventually become the most consequential product of this transformation.

The crisis provoked by the 1924 assassination of Giacomo Matteotti accelerated the dismantling of democratic safeguards and made a formal political police appear necessary to the dictatorship. Mussolini’s January 1925 declaration of responsibility for the political climate and his subsequent laws abolishing freedom of association and press autonomy marked a decisive rupture with parliamentary norms.5 The Ministry of the Interior reorganized its apparatus to ensure more reliable control, and police prefects gained greater authority over surveillance. This restructuring created the administrative space into which the future OVRA would be inserted, an entity designed to prevent dissent rather than merely punish it.

Arturo Bocchini’s appointment as chief of police in 1926 supplied the regime with a figure capable of designing an intelligence system suited to a modern authoritarian state. Bocchini professionalized the investigative services, reorganized regional commands, and standardized the reporting practices that would later define OVRA operations.6 His efforts also brought Italy into closer alignment with other European states that were developing political police systems, although the Italian model retained its own administrative character. Bocchini’s leadership ensured that repression operated through continuity, documentation, and bureaucratic presence instead of visible public violence, giving the dictatorship a more stable foundation.

The legal basis for a centralized political police expanded through the Exceptional Laws of 1926, which outlawed opposition parties and created the Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State.7 These measures supplied the mechanisms through which dissidents could be surveilled, tried, and removed from public life, but they did not yet constitute the OVRA itself. Instead, they established the judicial and administrative environment in which a political intelligence service could function effectively. The regime sought to integrate surveillance with legal repression, ensuring that political policing appeared consistent with the dictatorship’s claim to restore order and consolidate national unity.

Within this new institutional landscape, the OVRA took shape in 1927 as a distinct organization responsible for covert observation and the identification of political adversaries.8 Although its name remained deliberately ambiguous to conceal its size and procedures, its functions were clear: the OVRA served as an arm of the state devoted to discovering threats before they could manifest publicly. Its development marked the culmination of the regime’s transition from informal coercion to structured repression. By grounding its authority in bureaucratic procedure rather than paramilitary activity, the OVRA became an enduring component of Fascist rule and a model of how authoritarian governments convert insecurity into institutional permanence.

Internal Surveillance, Informers, and the Mechanisms of Social Control

The OVRA’s expansion into everyday Italian life relied on a surveillance model that combined bureaucratic oversight with widespread informal participation. This hybrid system allowed the organization to extend its reach far beyond its relatively small corps of official agents. Instead of building a massive uniformed presence, the OVRA cultivated a network of individuals whose observations and reports helped the police identify dissent before it became visible.9 The success of this model depended on the perception that observation was constant, a perception created less by direct encounters with police officers than by the awareness that anyone might serve as a conduit to state authority.

Central to this structure was the recruitment and management of informers, whose presence shaped the ordinary routines of social life. OVRA informers came from many backgrounds, including civil servants, workers, clerks, and individuals with longstanding political grievances.10 Their participation reflected both coercion and opportunism, since some joined to avoid scrutiny while others did so for financial or personal advantage. The organization maintained detailed files on these informers and evaluated their reliability over time. This system provided the regime with a flow of information that crossed class lines, regional boundaries, and occupational settings.

The reports generated by the informer network fed into an elaborate system of classification and documentation. Police offices compiled dossiers that recorded individuals’ political affiliations, personal relationships, employment histories, and public behavior.11 The OVRA integrated these materials into an archive used to track potential dissidents and monitor their activities across provinces. Surveillance therefore became an administrative process, one that operated quietly through paperwork, memoranda, and periodic updates rather than through constant visible policing. The presence of these files reinforced the idea that the state knew an individual’s background and movements even when no direct investigation was underway.

This administrative model supported a broader strategy of social control that encouraged citizens to avoid activities that might attract official attention. The knowledge that informers existed in neighborhoods, workplaces, and social organizations made open dissent appear risky.12 People moderated their speech in public settings and limited contact with known or suspected anti fascists. The unpredictability of denunciation became one of the OVRA’s most effective tools, because citizens had little ability to distinguish between genuine informers and individuals who simply behaved cautiously. The regime’s authority therefore depended not only on the actions of its agents but also on the psychological effects of uncertainty.

The surveillance network also targeted institutions viewed as potential centers of independent influence. Labor unions, professional associations, religious organizations, and cultural circles all appeared in OVRA reports when their members criticized official policies or expressed loyalty to traditions outside the Fascist framework.13 The political police monitored leaders of these groups and sometimes intervened to remove individuals judged to be dangerous or disloyal. These interventions did not always result in arrest or exile. Often they involved warnings, transfers, or administrative pressure that discouraged further activity. Such tactics reflected the regime’s preference for preventive measures designed to neutralize opposition quietly.

Although the OVRA seldom engaged in dramatic public operations, its influence permeated the daily life of the dictatorship. The cumulative effect of surveillance, recruitment, documentation, and targeted intervention produced an environment in which the boundaries of acceptable behavior narrowed steadily.14 Citizens learned that the cost of openly challenging Fascist authority could be severe, even if the mechanisms of repression remained largely invisible. This combination of quiet observation and selective punishment contributed to the stability of Mussolini’s rule by discouraging organized opposition and reinforcing a sense of vulnerability among those who doubted the regime’s legitimacy.

Repression, Censorship, and Legal Instruments of Control

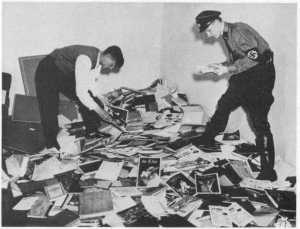

The OVRA operated within a legal framework that allowed Mussolini’s government to suppress dissent while maintaining the appearance of judicial procedure. The regime presented its actions as efforts to defend national security, yet the instruments of repression served primarily to eliminate political rivals and enforce ideological conformity.15 Censorship became one of the earliest tools for controlling expression. Newspapers, journals, and publishing houses faced constant supervision through directives issued by the Press Office, while regional prefects implemented local restrictions that limited critical reporting.16 Foreign publications were subject to seizure, and editors who attempted to preserve independent editorial lines encountered administrative pressure or the revocation of their licenses.

The system of censorship extended beyond the press to include theater, film, literature, and correspondence. OVRA agents reviewed performances and manuscripts judged to be politically sensitive, often intervening before works reached the public.17 Private letters and telegraphic communications were monitored as part of a broader effort to prevent the spread of dissenting ideas. This surveillance was not always uniform, but its presence created uncertainty that encouraged self-restraint among writers, artists, and ordinary citizens. The control of cultural production reinforced the Fascist narrative of national unity and discouraged alternative accounts of Italy’s social and political conditions.

The Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State became the primary judicial mechanism for prosecuting political crimes. Created in 1926, the tribunal heard cases involving alleged subversion, espionage, and anti-Fascist organizing.18 Its procedures favored the state, and convictions often rested on OVRA reports, intercepted correspondence, or testimonies from informers. Sentences included long terms of imprisonment and, in some cases, capital punishment. The tribunal’s decisions signaled the regime’s willingness to use legal authority to silence opponents and provided a formal venue through which political repression could be disguised as judicial necessity.

A distinct form of punishment, internal exile or confino di polizia, allowed the regime to remove individuals without a formal trial. Police authorities could order dissidents to remote islands or rural towns, often for years at a time.19 These measures disrupted social networks and prevented anti Fascists from organizing collectively. Confino also served as a preventive tool, applied to individuals suspected of disloyalty even when concrete evidence was lacking. By relocating political activists, intellectuals, labor leaders, and sometimes their families, the regime weakened organized opposition and demonstrated the consequences of defiance.

These instruments of repression functioned together to create a political environment in which dissent appeared futile. The OVRA’s intelligence reports informed decisions about arrests, censorship, and exile, while the legal system provided the framework for formalizing punishment.20 Citizens recognized that boundaries of permissible behavior had narrowed and that questioning the regime carried significant personal risk. Through the integration of surveillance, censorship, and judicial power, the Fascist state developed a comprehensive system of control that limited political pluralism and reinforced Mussolini’s authority.

International Operations and Fascism’s Transnational Surveillance Ambitions

The OVRA extended its work beyond Italy’s borders as Mussolini pursued a foreign policy aimed at consolidating Fascist influence in the Mediterranean and countering anti-Fascist movements abroad. Surveillance of expatriate communities became an important aspect of this strategy. Italian consulates, cultural institutes, and community organizations provided channels through which the political police could identify dissidents who had fled the country or who sought to mobilize resistance from overseas.21 Reports from diplomatic staff and informers helped the OVRA track political exiles and their contacts, particularly in France, Switzerland, and the Americas, where large Italian communities lived under governments that permitted open criticism of the regime.

The political police developed collaborative relationships with sympathetic intelligence services. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Italy increased its coordination with the Spanish security apparatus during the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera and strengthened ties again during the Spanish Civil War.22 Cooperation intensified with Nazi Germany after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, although the two regimes retained distinct organizational cultures. Italian agents and German counterparts exchanged information about communist movements, labor organizers, and political exiles.23 These interactions reflected a broader effort among authoritarian states to develop networks of intelligence sharing that reinforced their domestic agendas.

The OVRA also monitored anti-Fascist organizations operating from abroad. Groups such as Giustizia e Libertà, founded by exiled intellectuals, organized clandestine publications, sabotage missions, and propaganda campaigns aimed at undermining the dictatorship.24 OVRA agents attempted to intercept their communications, identify their members, and disrupt their networks. The political police relied on surveillance conducted by foreign authorities where possible, although the success of these efforts varied depending on the host country’s political climate. France, for example, offered greater protection to exiles, which limited the regime’s ability to intervene directly.

In regions targeted by Italian imperial expansion, intelligence activities served strategic and military purposes. In East Africa, the OVRA contributed to the consolidation of Italian rule after the conquest of Ethiopia in 1936 by gathering information on local resistance and monitoring interactions between Italians and subject populations.25 Intelligence work supported colonial security operations and helped identify areas where anti-colonial sentiment threatened the regime’s authority. Surveillance abroad therefore became intertwined with ambitions for territorial expansion and the construction of an Italian empire.

The political police also monitored the movements of Italian workers and migrants whose travel raised concerns about exposure to democratic or socialist ideas. The regime encouraged the formation of Fascist clubs among expatriates and used these organizations to promote loyalty to Mussolini while discouraging independent political activity.26 OVRA agents collected information on meetings, publications, and associations considered hostile to Fascism. The goal was not simply to track individuals but to prevent the formation of communities capable of sustaining ideological alternatives to the dictatorship.

International surveillance contributed to the regime’s image as a state capable of exercising influence beyond its borders. Mussolini sought to portray Fascism as a global force with the capacity to shape political movements abroad.27 Although the practical reach of the OVRA was limited by diplomatic constraints and foreign legal systems, its activities demonstrated the regime’s determination to monitor and contain opposition wherever it emerged. The combination of cooperation with other authoritarian states, monitoring of diaspora communities, and intelligence work in colonial territories revealed the transnational dimensions of Fascist repression and its role in sustaining the dictatorship’s broader ambitions.

Decline, Collapse, and Historical Legacy of the OVRA

The OVRA’s effectiveness began to erode as the international situation shifted in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Italy’s entry into the Second World War placed new pressures on the dictatorship, and the demands of military mobilization strained the institutional capacities of the political police. Shortages of personnel, communication disruptions, and the redirection of resources toward military intelligence limited the organization’s ability to sustain its earlier level of surveillance.27 As public morale deteriorated and confidence in Mussolini declined, the political environment grew more volatile, making it increasingly difficult for the OVRA to manage dissent through its customary preventive methods. The organization remained active, but it no longer possessed the stability that had characterized its earlier years.

The collapse of the Fascist regime in July 1943 and the subsequent German occupation of central and northern Italy transformed the structure of political policing. After Mussolini’s removal by the Grand Council and the formation of the Badoglio government, the state’s repressive apparatus fractured.28 When the German authorities reinstated Mussolini as head of the Italian Social Republic, control over internal security shifted toward German agencies, particularly the Sicherheitsdienst.29 The OVRA continued to operate in a diminished form within the new puppet state, but its influence was overshadowed by the priorities of the occupying power. The resulting fragmentation revealed how dependent the organization had been on the administrative coherence of the original Fascist state.

In the immediate postwar period, the documentation left behind by the OVRA became an important resource for judicial inquiries and historical reconstruction. Italian authorities investigated former officials, though prosecutions were limited by the political complexities of the new republic and the Cold War environment.30 Archivists and scholars gained access to reports, dossiers, and administrative correspondence that illuminated the scope of surveillance during the dictatorship. These materials helped historians analyze the regime’s internal dynamics and provided insight into the strategies used to police dissent. The existence of such records distinguished Italy from some other authoritarian states where documentation was destroyed or dispersed.

The legacy of the OVRA continues to shape interpretations of Fascism and authoritarianism in modern Europe. Scholars have examined the political police not only as an institution of repression but also as a mechanism through which the regime sought to reorganize society and influence everyday behavior.31 The OVRA’s methods demonstrated how a dictatorship could integrate surveillance into ordinary life without relying exclusively on visible terror. Its history remains a reminder of the vulnerability of civil liberties in periods of political instability and of the ways in which bureaucratic systems can normalize coercion. By understanding the OVRA’s rise and collapse, historians gain a clearer view of the structures that sustain authoritarian power and the fragility of such systems when confronted with war, economic strain, and internal dissent.

Conclusion

The history of the OVRA reveals how the Fascist state harnessed surveillance and bureaucracy to manage political life and suppress dissent. Its structure developed gradually from a combination of administrative centralization, legal innovation, and the cultivation of informant networks that penetrated many areas of society.32 The organization did not rely on spectacular violence to enforce obedience. Instead, it operated quietly through documentation, careful observation, and targeted intervention. This approach demonstrated Mussolini’s belief that a modern dictatorship required continuous oversight of citizens’ behavior and the capacity to intervene early, long before organized resistance could take shape. The OVRA served as the institutional embodiment of this strategy.

The work of the political police also illustrated the tensions within the regime’s vision of order. The OVRA presented itself as a rational instrument designed to protect the state, yet its effectiveness depended on a social environment marked by distrust, intimidation, and the erosion of public life.33 Surveillance narrowed the boundaries of political participation and discouraged open debate, while censorship restricted access to competing narratives. These practices reshaped Italy’s civic landscape and contributed to the consolidation of a system that prized ideological conformity over pluralism. The OVRA became both a symptom and a cause of the dictatorship’s inability to tolerate genuine political diversity.

Although the OVRA collapsed with the fall of Fascism, its legacy endured in the records it left behind and in the historical questions it raised about the relationship between state power and civil society. Scholars have used its archives to examine the mechanisms through which authoritarian regimes manage opposition, cultivate loyalty, and influence public behavior.34 The history of the OVRA remains a reminder of how quickly institutions of surveillance can become embedded in political structures and how difficult they can be to dismantle once established. By studying the OVRA, historians gain insight into the broader dynamics of repression in the twentieth century and into the fragile foundations on which authoritarian systems rest.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Emilio Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 203–210.

- Christopher Duggan, The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007), 455–460.

- Richard J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy: Life Under the Dictatorship, 1915–1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 313–320.

- R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini and the Eclipse of Italian Fascism: From Dictatorship to Populism (Hartford: Yale University Press, 2021), 42–49.

- Emilio Gentile, The Struggle for Modernity: Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism (Westport: Praeger, 2003), 133–140.

- Christopher Duggan, Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 91–95.

- Philip Morgan, Italian Fascism, 1915–1945 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 82–86.

- Mauro Canali, Le spie del regime: L’OVRA, gli agenti, la repressione politica in Italia (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2004), 21–28.

- Ibid, Le spie del regime, 45–53.

- Ibid, Le spie del regime, 74–82.

- Jonathan Dunnage, The Italian Police and the Rise of Fascism: A Case Study of the Province of Bologna, 1897–1925 (Westport: Praeger, 1997), 164–169.

- R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy: Life Under the Dictatorship, 1915–1945 (New York: Penguin, 2006), 314–320.

- Gentile, The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy, 256–262.

- Gentile, The Struggle for Modernity, 152–159.

- Philip V. Cannistraro, La fabbrica del consenso: Fascismo e mass media (Rome: Laterza, 1975), 87–96.

- Stephen Gundle, Mussolini’s Dream Factory: Film Stardom in Fascist Italy (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 34–42.

- Mauro Canali, Il delitto Matteotti e la nascita della dittatura fascista (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1997), 241–249.

- Giulia Albanese, Dittature mediterranee: Sovversioni fasciste e colpi di Stato in Italia, Spagna e Portogallo (Rome: Carocci, 2016), 112–119.

- Paul Corner, The Fascist Party and Popular Opinion in Mussolini’s Italy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 173–180.

- Giovanni De Luna and Adolfo Mignemi, Storia fotografica della Repubblica sociale italiana (Milan: Bollati Boringhieri, 1997), 187–195.

- Davide Rodogno, Fascism’s European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 72–78.

- Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 158–162.

- Claudio Pavone, Una guerra civile: Saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1991), 54–61.

- Angelo Del Boca, Italiani in Africa Orientale, vol. 3 (Rome: Laterza, 1986), 219–226.

- Gianfranco Cresciani, Fascism, Anti Fascism, and Italians in Australia, 1922–1945 (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1979), 41–49.

- Bosworth, Mussolini’s Italy, 350–357.

- John F. Pollard, The Fascist Experience in Italy (London: Routledge, 1998), 142–148.

- Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 284–291.

- Lutz Klinkhammer, L’occupazione tedesca in Italia 1943–1945 (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1993), 103–111.

- Mimmo Franzinelli, I tentacoli dell’OVRA: Agenti, collaboratori e vittime della polizia politica fascista (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1999), 359–366.

- Philip Morgan, Fascism in Europe, 1919–1945 (London: Routledge, 2002), 219–224.

- John Foot, Italy’s Divided Memory (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 56–63.

- Simon Levis Sullam, The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 27–34.

- Ruth Ben Ghiat, Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 211–218.

Bibliography

- Albanese, Giulia. Dittature mediterranee: Sovversioni fasciste e colpi di Stato in Italia, Spagna e Portogallo. Rome: Carocci, 2016.

- Ben Ghiat, Ruth. Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Bosworth, R. J. B. Mussolini and the Eclipse of Italian Fascism: From Dictatorship to Populism. Hartford: Yale University Press, 2021.

- —-. Mussolini’s Italy: Life Under the Dictatorship, 1915–1945. New York: Penguin, 2005.

- Burleigh, Michael. The Third Reich: A New History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.

- Cannistraro, Philip V. La fabbrica del consenso: Fascismo e mass media. Rome: Laterza, 1975.

- Canali, Mauro. Il delitto Matteotti e la nascita della dittatura fascista. Bologna: Il Mulino, 1997.

- —-. Le spie del regime: L’OVRA, gli agenti, la repressione politica in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2004.

- Corner, Paul. The Fascist Party and Popular Opinion in Mussolini’s Italy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Cresciani, Gianfranco. Fascism, Anti Fascism, and Italians in Australia, 1922–1945. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1979.

- Del Boca, Angelo. Italiani in Africa Orientale. Vol. 3. Rome: Laterza, 1986.

- De Luna, Giovanni and Adolfo Mignemi. Storia fotografica della Repubblica sociale italiana. Milan: Bollati Boringhieri, 1997.

- Duggan, Christopher. Fascist Voices: An Intimate History of Mussolini’s Italy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- —-. The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

- Dunnage, Jonathan. The Italian Police and the Rise of Fascism: A Case Study of the Province of Bologna, 1897–1925. Westport: Praeger, 1997.

- Foot, John. Italy’s Divided Memory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Franzinelli, Mimmo. I tentacoli dell’OVRA: Agenti, collaboratori e vittime della polizia politica fascista. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1999.

- Gentile, Emilio. The Sacralization of Politics in Fascist Italy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- —-. The Struggle for Modernity: Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism. Westport: Praeger, 2003.

- Gundle, Stephen. Mussolini’s Dream Factory: Film Stardom in Fascist Italy. New York: Berghahn Books, 2013.

- Klinkhammer, Lutz. L’occupazione tedesca in Italia 1943–1945. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1993.

- Levis Sullam, Simon. The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Mack Smith, Denis. Mussolini. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

- Morgan, Philip. Fascism in Europe, 1919–1945. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Pavone, Claudio. Una guerra civile: Saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1991.

- Pollard, John F. The Fascist Experience in Italy. London: Routledge, 1998.

- Rodogno, Davide. Fascism’s European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.