The story of the Blackshirts and Brownshirts is not merely about uniforms and marches. It is about how performance created belonging, how intimidation became ritual, and how violence evolved into legitimacy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Long before memes, fascists used uniforms and marching songs to bind followers into movements that made violence feel inevitable. The insight resonates with chilling clarity when one considers the Blackshirts of Fascist Italy and the Brownshirts of Nazi Germany. These paramilitary groups were not accidental side effects of fascism. They were its muscle, its theater, and its proving ground.

Paramilitary politics in the early twentieth century reveals how performance and intimidation worked hand in hand with brute force. These movements cultivated identity through spectacle as much as through violence. The street became both battleground and stage, where uniforms, salutes, and slogans communicated as powerfully as fists, truncheons, or bullets.

Origins of Paramilitary Mobilization

Italy’s Blackshirts

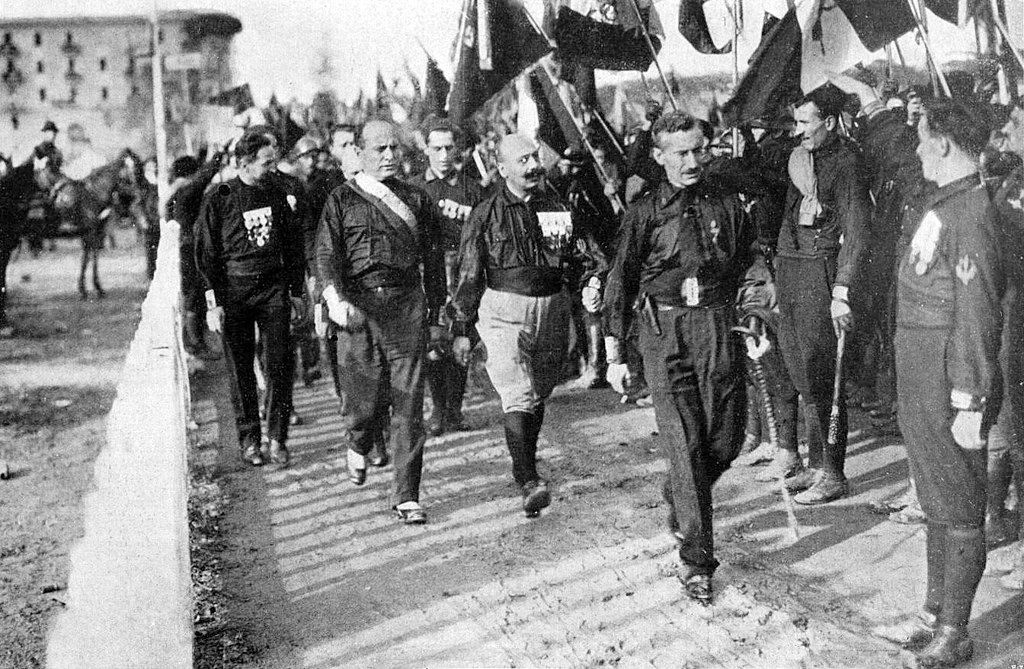

The Italian Squadristi, known as the Blackshirts, emerged in the chaotic years after the First World War. Veterans returning from the front encountered economic dislocation, political turmoil, and a state that seemed incapable of stability. Benito Mussolini seized upon this discontent, promising order and national revival. His followers donned black shirts as uniforms of militancy, turning simple clothing into a declaration of allegiance.1

The Blackshirts attacked socialist offices, intimidated trade unionists, and paraded through towns to demonstrate dominance. Violence and performance were inseparable. Each assault communicated not only raw power but also the message that the Fascists embodied Italy’s future.

Germany’s Brownshirts

Germany’s Sturmabteilung (SA), or Brownshirts, arose in a similarly unstable environment. The Weimar Republic was burdened by the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation, and political polarization. Adolf Hitler’s Nazi movement offered identity and direction to disoriented citizens. The brown uniforms, initially surplus from colonial troops, became symbols of unity and defiance.2

The SA excelled at orchestrated disruption. They broke up political meetings, marched through working-class neighborhoods, and staged massive rallies. As with the Blackshirts, their violence was never mere brutality; it was performance designed to humiliate enemies and embolden supporters.

Performance as Politics

Uniforms and Collective Identity

Clothing served as a visual manifesto. Black and brown shirts created instant recognition, erasing individuality in favor of collective identity. To wear the shirt was to declare loyalty not only to a leader but to an imagined nation reborn.

The effect was theatrical. Spectators saw columns of men in uniform and perceived strength, unity, and inevitability. Opponents felt fear, while sympathizers felt pride. The uniform translated ideology into fabric, turning abstract ideas into visible presence.

Songs, Slogans, and Rituals

Marching songs and slogans worked as mnemonic devices, embedding ideology into rhythm and sound. The Blackshirts’ anthem “Giovinezza” and the Brownshirts’ “Horst Wessel Lied” were not just tunes. They were vehicles of propaganda that created emotional bonds and turned rallies into communal rituals.3

These rituals fused entertainment and menace. A parade was at once a spectacle of belonging and a warning of what awaited dissenters. The ritualized shout, the raised arm, and the rhythmic chant were not accidental flourishes; they were carefully designed to bind members together and intimidate opponents.

Violence as Spectacle

The Street as Stage

The Blackshirts and Brownshirts understood that the street was both battlefield and theater. Street fights against communists or socialists were staged as evidence of the state’s weakness and fascism’s vigor. Each confrontation provided a script in which fascists were protagonists defending the nation against traitors.

Crowds played a vital role. Witnessing violence transformed it into a public lesson. Those who watched learned what it meant to oppose fascism, while sympathizers learned how power looked when performed. Violence was never private; it was a civic ritual broadcast to all.

From Intimidation to Legitimacy

Over time, repeated acts of violence normalized the presence of paramilitary groups. Citizens grew accustomed to seeing men in uniform patrolling, shouting slogans, or attacking opponents. What began as disruption became a claim to legitimacy. If the state could not control the streets, the paramilitaries would. And if they controlled the streets, why not the state itself?

This logic smoothed Mussolini’s march on Rome in 1922 and facilitated Hitler’s rise a decade later. Violence, ritualized and performed, made fascism appear not only possible but inevitable.

The Aesthetics of Fascism

The Blackshirts and Brownshirts mastered aesthetics as politics. Their uniforms, rallies, and salutes constituted a symbolic language. To participate was to inhabit a role. To observe was to internalize a message.

This aesthetic strategy resonates today in digital form. Online extremist communities cultivate belonging through memes, hashtags, and visual motifs. The meme functions as the uniform, instantly recognizable, signaling loyalty and inviting participation. Like the marching song or salute, it communicates allegiance while appearing informal or ironic.

The continuity is striking: whether through shirts and songs or avatars and memes, fascist movements have long relied on symbolic performance to transform individuals into collectives and violence into destiny.

Historical Consequences

The paramilitary politics of the Blackshirts and Brownshirts did more than destabilize fragile states. They transformed cultural norms, blurring the line between politics and war. Once the shirt was worn and the chant repeated, violence followed as the logical next act.

Historians emphasize that without these paramilitary groups, neither Mussolini nor Hitler could have ascended so quickly. Their movements demonstrated that force, staged as theater, could both undermine democracy and lay the foundations for dictatorship.4

Conclusion

The story of the Blackshirts and Brownshirts is not merely about uniforms and marches. It is about how performance created belonging, how intimidation became ritual, and how violence evolved into legitimacy. Their strategies remind us that politics is not only about institutions or elections but also about symbols, bodies, and the street.

In the twenty-first century, extremists who cultivate identity online echo these lessons. Memes and avatars replace shirts and songs, but the logic remains: symbols bind, rituals sustain, and performance prepares the way for violence.

The paramilitary politics of the past continues to whisper into the present, urging vigilance against movements that turn culture into weaponry and spectacle into power.

Appendix

Notes

- Emilio Gentile, The Origins of Fascist Ideology, 1918–1925 (New York: Enigma, 1975).

- Richard J. Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003).

- Peter Fritzsche, Germans into Nazis (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Stanley Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914–1945 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995).

Bibliography

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin, 2003.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Germans into Nazis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Gentile, Emilio. The Origins of Fascist Ideology, 1918–1925. New York: Enigma, 1975.

- Payne, Stanley. A History of Fascism, 1914–1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.15.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.