Lecture (October 1942) by Dr. Floyd Seyward Lear

Late Professor of Ancient History

Rice University

I

Others shall beat out the breathing bronze to softer it well; shall draw living lineaments from the marble; the cause shall be more eloquent on their lips; their pencil shall portray the pathways of heaven, and tell the stars in their arising: be thy charge, 0 Roman, to rule the nations in thine empire; this shall be thine art, to lay down the law of peace, to be merciful to the conquered and beat the haughty down.[1]

In these noble words Rome’s poet of empire declared her imperial mission to the world and defined the native genius of her citizens to consist in the power of rule, of government and of law. Indeed, the Romans were a lawyerly people with a lawyerly habit of mind, marked early and lasting late in their history – a people of lawyers, administrators and statesmen. They were solid, substantial, cautious and conservative within reason; they were practical, sometimes unimaginative, industrious, frugal, and very much businessmen. The forum and the courts often joined hands with the market place, and under no circumstances do we find them fearful of hard work. Seldom do they remind us of the facile, sophisticated, curious, and critical Athenians whom St. Paul encountered in the famous episode on Mars Hill and who, as he tells us, “spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell or to hear some new thing.”[2] These people did not confuse novelty with wisdom, change with progress, or activity with virtue. They had formed the habit of suspended judgment, long mental reservation, but also of decisive action, pursued firmly to an irrevocable end- an end which all subject peoples knew would be attained and, once attained, could never be recalled. Perhaps it was this sense of the inevitable outcome lending its dark inspiration of the fatum romanum and combining with the imponderable massiveness of Roman power that guaranteed the indestructibility of Rome and made her the Eternal City of that world wherein she ruled.

Such crushing might brought the feeling of helplessness and frustration, of hopelessness and dismay which lay heavily across the path of Rome’s advance. Also the lack of elasticity and aesthetic attraction, as Foligno has observed, awakens an instinctive antagonism and even repulsion in the modern mind;[3] yet one may glimpse a very different view of the meaning of Roman power if he listens to Respighi’s magnificent interpretation in the Pines of the Appian Way.[4] To me the irresistible measured tread of the advancing legions in the early dawn suggests not only the defeat and subjugation that preceded the night now passed, but order, law, and peace in the bright sunlight of the new day. It tells of the despair, anguish, and desolation of conquest, but also of the hope and opportunity of a larger and more universal society. Rome humbled but Rome exalted as well, as St. Paul bears witness in his pride of Roman citizenship. It has been said that Rome differs from all the empires that came before her inasmuch as she represents conquest with assimilation, whereas her predecessors from ancient Sumer to the Hellenistic monarchies conquered but did not assimilate.

Rome levelled her subjects in crashing, shattering defeat and then lifted them up to share a pride in her that could capture the discriminating Jewish intelligence of a Paul. Her supreme victory came when the superiority and desirability of her civilization were admitted among civilized men. The pax romana was peace imposed by force of arms but a peace which was spread over more peoples and over a longer time than in any comparable period of history. It was a unique feat in a world that has always been cursed with wars and rumors of wars, and it is this paradox of the defeated sharing the victory despite bloodshed, servitude, and ruin that has baffled many superficial critics of Roman civilization. The Roman lived empire ; others have built and lost empires, but none other has been empire incarnate. \\’hat manner of man was this Roman? Queried Shower- man: “Who is this man who taught the nations of the earth at first to obey and respect, and finally to love, his mistress Rome ?[5]

Dr. T. R. Glover, a profound student of antiquity, re- marks that the Greek who took the trouble to study him found him a very curious and interesting character who “thought in an utterly different way from all the familiar types of the world,” and relates the old story of Kineas, the ambassador of Pyrrhus, who returned from Rome to tell his king that Rome was ruled by an assembly of kings; so impressive was the majesty of the Roman Senate.[6] And, in general, it may be observed that the Roman proconsul at his best represented the noblest example of enlightened rulership that has ever administered the affairs of vast human masses. At this point, surprising though it may appear, we discover that the great proconsul whose life was the epitome of public service spoke a language which had no specific word for patriotism. Still more ironical does it appear when we recall that our English word is derived from the Latin stem, so that the language which bequeathed us patriotism as a part of our Latin linguistic heritage gave us a word that it never possessed.[7] However, the essential concept was never lacking when the Roman spoke of patriae amor, or pietas erga patriam, or reipublicae studium. It is the stem, not the abstract expression, wherein we find the root of life. It is to the patres, to the fathers, that we must turn to understand the foundations of Roman character, for the great proconsul is patriotism personified. Love of his native land is never divorced from reverence (pietas) for the maiores, his forebears, the greater ones who have preceded him and paved the way for the present society. Indeed, it is true that he worshipped the spirits of his ancestors and placed their death-masks, the imagines maiorum, in the places of honor within the atrium or great hall of his home as a mark of respect, a bit after the manner of the family portraits in the parlors of respectable American homes perhaps a generation ago, homes which we hope have not entirely vanished. Here the likenesses of his relatives reposed to lend reality to the tales which he had heard repeated at his grandfather’s knee, and here they remained undisturbed save for solemn occasions as when they were carried in the funerary processions in observance of ancient ritual. Similarly he worshipped the Lares and Penates, the deities of hearth and home who guarded nature’s bounty and domestic prosperity, extending their divine sanctions over the household, and whose figures were also a familiar homely sight. In all important activities of life, public and private alike, the great proconsul knew that the maizes or shades of his fathers enclosed him in their protecting shadows and directed his public acts and his private conduct much as the spirit of the departed Anchises warned Aeneas, and as his own father, when living, had guided and advised him in his youth. In turn he counselled his own son and received the obedience of his family which was owed in law and custom to the patria potestas, the power of the father, that made him king over his household with an authority ex- tending to life and death within his domestic circle. Also like the great gods themselves he was cloaked in the majesty of the father, the maiestas patris, which expressed the sacred rule of parenthood inhering in the father as parens and the holy awe felt €or the procreator of his line.[8] The ties which bind the members of families extend throughout Roman society and depend upon the concept of piety, pietas. This has none of the modern Christian connotation of religious emotion as an aspect of the inner spiritual life but implies the filial obligations which unite the individual to his parents, superiors, or country as manifested in concrete acts of devotion and in the specific reflection of character. Thus, Aeneas is always pius Aeneas. But the supreme pietas consists in being the son of the fatherland (patriae filius), as Cicero remarks in his First Oration against Catiline when he says that the fatherland is the common parent of us all.[9] Accordingly the crime of parricide whether it be directed against parents or fellow-citizens is the most heinous offense against pietas, and it forms the legal basis from which the Roman conception of treason (perduellio) and the crimes against majesty develop. The deepest impiety of which any man was capable was displayed by attacking or betraying his native land.[10] Collectively these heads of families, extensive kinship groups bound by common ties of blood, met in that assemblage of kings that Kineas saw, the Roman Senate, the greatest deliberative and policy-making body of the ancient world. In the earlier years of the Republic before the Publilian Law, the general assembly of the people, the comitia centuriata, could not legislate without the assent of the fathers, the auctoritas patrum. Later their advice alone was sufficient, and the prestige of the senatus consulta carried the force of law. Public action was inconceivable without the authority of the elders of the state. Auctoritas is the hallmark of the proconsul in his every act; it is the patriotic will in action; it is also the tradition of rule and of empire.[11] The Roman never forgot his ancestors or his pride in them, but he never forgot that he must rely on him- self in his rulership to be worthy of them. He never doubted that men are unequal or that he was superior, and the world accepted him at his own valuation.

Let us survey a little more fully the mental climate within which the great’ proconsul developed his strange, curious, and interesting character. The Latin language possesses a certain capacity for terse, compact, abstract expression which our uninflected English cannot attain with its casual syntax, joined loosely with conjunctions and strung on a frail lattice- work of prepositional modifiers and dangling participles that tend to trail away vaguely into the dim regions of in- completed thought. In contrast with this unformed expression the Latin builds its sentence-structure solidly with word mortared to word until the finished edifice emerges in a marmoreal temple of reasoned periods and lucid analytical construction. Logical, clear and precise, the Latin forms an incomparable linguistic instrument moving forward irresistibly with a coordinated beat, a measured tread, a rolling surge of sound suited to the thought, which reminds us of the marching legions that spoke and sang this tongue : Erce Caesar nunc triumphat qui subegit Gallias! However, what the classical measures gained in their power and majesty handicaps them ofttimes in the search for grace, delicacy, and refinement of expression. In the main, Latin is better suited to describe character than to paint a romantic picture or adorn a sentimental tale. Hence, one is agreeably pleased to discover in this language a wealth of abstract expressions that are sometimes described as the “Roman character-words.”[12] It may be profitable to analyze several such terms if we wish to comprehend the inscrutable pro- consul. These specifically Roman qualities reflect a certain attitude toward life, reveal a well-defined perspective in which the Roman beheld his world and its inhabitants, and express principles of conduct especially adapted to a nation whose mental habits were predominantly military, legal, and political. Among historical figures who bulk large in the arena of Roman public life none displayed these traits more typically than Cato the Senator who lived in the great days of the Republic after the great victories had been won over Carthage, while the nation was in the vital process of creating the Empire, and before the inertia and inner decay had appeared which are the symptoms of that fatal malady of states that can find no more worlds to conquer, before Rome paid the price of her total and unqualified material success. To some these traits may seem to betray the limitations of the Roman soul as if devoid of positive spiritual value; to others they may appear an exaltation of the material man and his earthly nature transcending the limitations of human environment and abstracting from his thought those elements of reason and virtue which claim kinship with divinity.

Among these traits four must be considered so essential to the complete Roman that defect in any one of them might properly be regarded as failure to attain a well balanced, rightly proportioned character. Perhaps we should name virtus first since it proceeds from the inner life, the inner man himself.[13] It baffles translation, although one must acknowledge that for the finest and most discriminating sense there can never be such a thing as translation. It is nearly impossible to carry ideas across from one mental region to another, preserving their original identity at the same time. At best one seeks a similar idea native to its region and climate, and clad in the mental garb of its people. However, virtus may be described as an active function of man : manliness, positive courage, individual vigor, and fearlessness. Also it involves intellectual power, firmness, and strength. It is the essential inherent moral faculty that brings courage to meet obstacles with valor. It implies the mental directness to perceive and appreciate things as they are, the aptness and capacity to discern accurately and correctly, to be alive to the realities of a situation, even the power of discrimination so necessary to sound legal judgment and political decision. This word has had an interesting later history since it is a part of the classical heritage of the modern Romance languages and of English as well which is in great part derived from Latin. It emerges in Renaissance Italian as virus, that skill or talent which succeeds and accomplishes its purpose, the possession of which aids much in the making of the full man, l’uomo universale. The new word reflects a prime characteristic of the age with its devotion to material ends and its admiration of individual achievement.[14] Thus, Cellini displays virtus whether he is designing a superlative button for the Pope’s cope or dispatching an enemy with an especially deceptive thrust of his dagger. In short, virtus is cleverness, and as such represents a profound deterioration in basic meaning from its classic original. It is, indeed, a bad word or at best amoral as the Princes of Machiavelli who applied it. Again this Latin word of strength emerges in modern English as virtue in the common sense of right living and good morals of the conventional sort. Virtue is a good word and suggests what is lovely, pleasing, and amiable, even moral perfection, but nonetheless there is still a deterioration, for virtue is a weak quality to pit against the virtus of Rome, unless we define it on that higher level which restores its intrinsic primary classical meaning and repeat after Lucilius:

Virtue, Albinus, is knowing how to set the true price upon the things among which we live and move and have our being; virtue is for a man to know all true values. Virtue is for a man to appreciate what is upright, useful, and honorable, what is bad as well as what is good, what is useless, base, and dishonorable. Virtue is to know the end and measure of getting. Virtue is to know how to place their true value upon riches, to give to honor what is really its due, to be the enemy and assailant of bad men and bad morals, but to be the defender of good men and good morals, to magnify and wish them well and be their friends; and, besides, to hold the good of one’s country first, the good of one’s kinsmen next, and one’s own good third and last of all (comnioda praeterea patriae sibi prima putare, deinde parentum, tertia inm postre- maque nostra).[15]

Consider what a powerful, comprehensive idea this is, and we may see that whether it became virtu or virtue or remained virtus depended solely on the ethical direction toward which an age inclined.

Just as no Roman was complete without virtus, none could command respect without fortitudo.[16] Fortitude is a word of which we had heard little for at least a generation until its restoration in glory at Corregidor, Bataan, and Guadalcanal with consequences for the American soul that one can scarcely envision. Our colonial forefathers were well acquainted with it and had much experience of it, but later it became a less used expression, more often than not associated with such unpleasant connotations as attach to duty, responsibility, and obligation. But to a Roman without fortitudo the individual had not attained the stature of a man. This explains why the Roman always walks across the pages of history as the grown man, the mature man of affairs. He lacks the capriciousness, the adolescent brilliance, and the color of the Greek, but one knows exactly where he may be found when a tight situation requires him to take his stand. The Roman stood his ground and did not abdicate his responsibility when other men ran away, seeking solace in the mysteries of magic and religion or taking refuge in the ivory towers of philosophy and science. That is why the great proconsul ruled the world which fell from the nerve- less hands of Hellenistic kings. One recalls the strange story of Antiochus Epiphanes who was preparing to assail his ancient enemy, the Ptolemies of Egypt, when a proconsular Roman visited the Syrian camp with a small retinue.[17] After some casual conversation, Antiochus, who had dwelt as a hostage in Rome for thirteen years and knew no Roman made so long a journey without reason, inquired his purpose. The answer of Popillius Laenas was curt: The Roman Senate did not wish the eastern king to attack Egypt. Seeking to delay the stubborn Roman, Epiphanes replied that he would consider the situation. But forthrightly Popillius drew a circle round about the king with his stick and issued his stern demand: “Give your answer before you pass this circle.” The king reflected and said : (‘I am returning to Syria.” It became a habit of proconsuls to deal with kings and potentates in this manner. I suspect this a poor example of fortitude and a better one of self-reliance, but it does re- veal the steadfastness and firmness which must be associated with the Roman concept. Fortitudo is a passive form of courage, harder to display than virtus, since one must possess an infinite capacity of patience to face the difficult, dis- agreeable, and threat of doubtful outcome for any length of time. It enabled the Roman to wear out his opponent and stare him out of countenance, even as Popillius drew his circle about the Syrian monarch. It made the Roman the most superb defender of the goal-lines of life that all time can show. Probably this granite-like quality derived from the Roman heritage of close contact with the soil. The pro- consuls were mostly members of the country gentry who lived on their landed estates and had not drawn root from the earth which lends men strength. Showerman says this Roman citizen-soldier had “the immoveableness of the unchanging country.” It gave the Roman his cold, glacial resistance to impetuosity, impulsiveness, and dangerous enthusiasms. Fortitudo recalled him to reason without which no man is fit to rule, without which man fails to recognize duty, responsibility, and obligation.

The third trait of character that must be considered in any examination of the Roman mind and spirit is an extremely important one because upon it are laid the foundations of the intellectual life of this great people. It is called prudentia but is not quite the same as that somewhat inert principle of emotional restraint and mental reservation known to us as prudence.[18] It connotes our idea of prudence with significant additions, and more nearly approximates that rather intangible thing which we call common-sense, whose very existence it has been fashionable to deny recently in certain smart circles. Probably it is unnecessary to remark that the cult of brightness never took hold upon the Roman imagination in the great days of the Republic. Of course, the Greeks insisted that the Romans had no imagination, but in all fairness the Roman concept of prudentia provides a point of departure for a very serious critique of Greek character. Against this background of practical wisdom and hard common-sense, one feels a certain inadequacy and futility in the Greek soul, a certain fatuousness in such practical concerns as politics and government which is borne out by the facts of history in the constant bickerings and civil wars between the city-states, and the antics of the Athenian democracy in its conduct of foreign affairs. The Romans would probably have agreed that every people enjoys precisely the sort of government that it deserves and would point to the disasters of the expeditions against Syracuse, the diffusion of naval and military power between Oenophyta and First Coronea, and the amazing negligence at Aegospotami as instances of the folly of sentimental popular politics. The Romans had their disasters also: the Punic wars were filled with them, but they had a tendency not to repeat their acts of foolishness. Beside all this and worse, one suspects in the Greeks a certain moral brittleness and some intellectual superficiality and shallowness. This was often combined with a lack of sympathy and understanding so that the Greek inclines to shed responsibility for his fellow-man, a defect which helps us to realize why the Greek with all his gifted nature could never rule the world. Thus, Lucian in his essay on “The Dependent Scholar” cries out: “You are a loose-principled, unscrupulous Greek. That is the character we Greeks bear; and it serves us right. I see excellent grounds for the opinion they (the Romans) have of us.”[19] It is true that the Roman hardly feels himself to be his brother’s keeper, but he is a lawyer who thinks of men in terms of human relationship and has a social outlook if not a social conscience. However, justice and equity in law lead inevitably to humanitarian applications of the statutes, and in the long run of events the law is a mighty force in the amelioration and renovation of society. The Roman had humanitarian potentiality, whereas the Greek remains a self-centered individualistic humanist. And, as Professor Greene has pointed out, humanism and humanitarianism are not the same or even necessarily related aspects of humanity.[20]

Prudentia, also, signifies some of the shrewdness and native wisdom associated with the rustic outlook, for even a proconsul was often a farmer who knew that nature is moody and uncertain and can be tamed only with fore- sight, thrift, and industry. Indeed, it was in the words of Cicero naturalis quaedam prudentia: a certain innate level-headedness bestowed by nature upon the Latin race. Prudentia taught him to keep his head in crises and dilemmas, to make a cool survey of an emergency with complete lack of recklessness, to decide if it were an emergency at all and act accordingly, and to take the long view ahead with adequate provision for the future. Prudence was also providence. Furthermore, it involved the idea of knowing how far one can go without doing damage to his cause, the wise, statesmanlike attitude of suspended judgment which implies the power of discrimination and capacity for right selection, in other words common-sense. Even here, as else- where in life, excess leads to defect. The prudent Roman is often stubborn and likely to consider himself to be always right. He is uncompromising, and, if he yields, it is not be- cause he appreciates his opponent but because he perceives a weakness in his own position. Idealist critics of the Romans may agree it is admirable that the Roman is a hard, common-sense business man, but they repeat that he can never be more than that, and therein proclaim the tragedy of the Roman soul. But the Roman did not worry about his critics, mostly Greeks and Orientals. He admitted that he was a practical man of the world and knew that the world soon fell in a bad way when men of his sort were not on hand to manage it, Therefore he made short shrift of the visionaries and reformers who were always agitating the Greek cities with their utopias and dreams of a new day, He enforced the Roman peace ; he maintained order under law and got on with the world’s work. The decrees of the Senate, the judgments of the praetor, and the commands of the proconsul were all reflections of that authority (auctoritas) which is the public will in action and which expresses the civil prudence of the body politic inherited from the authority and wisdom of the fathers (auctoritas et prudentia maiortim).

In the fourth place, no one can omit the quality of gravitas in any analysis of Roman character.*’ Indeed, some might regard this as the most significant and specifically Roman trait of all. Literally the word means weight and hence suggests importance and power. But, like the other “character-words,” it is a most difficult abstraction to define. This difficulty is enhanced since gravitas has a dual aspect, It refers to a certain quality of soul subsisting in the inner man, but also to its outward reflection with respect to personal appearance and manners. This tendency toward the materialization of spiritual elements pervades Roman life and thought deeply. It is doubtful that the Roman entertained or even comprehended the Socratic view of the soul as a central focus of personality which lies within our power to build for good or ill. The Roman tended to regard the individual personality as a fragment of society moulded by the infinite contacts and experiences of living. This was a humanism of human interests and relations arising out of the nature of society and the state, a human- ism of civic impulse. But Greek and Christian ideas de- rived from Platonism imply that man is the architect and sovereign of his soul beyond the reach of human laws and social conventions. This was a humanism of the self-sufficient, independent man creating his own spiritual and intellectual dominion. In truth, one may say that the Roman lacked a soul in the Socratic sense,[22] but possessed a genius, a concept which was as unfamiliar to his Greek contemporaries as to modern men. Perhaps the genius may be de- fined as the abstraction of a man’s personal qualities and characteristics, combined with such external features as would identify him in his proper place in society including his offices, military career, relatives, and family traditions. It was a material, rather than a spiritual, conception, the abstract collective popular opinion concerning a man, idealized in the light of what he would like others to think him to be. But a man’s genius was never the man himself. It could even be so personified and detached from the individual as to suggest a guardian angel or some superlative alter ego.[23] It must now be apparent that every Roman de- sired a worthy genius suited to the dignity of a Roman citizen. This implied a calm, serious outlook, dignified self- respect, and a certain sense of personal worth causing a man to take himself seriously. Also it involved a determination to live up to a man’s belief in himself, an aristocratic ideal above all small conceit. Indeed, the Roman eschewed carefully the common, modern confusion between self-respect and self-conceit. Said Livy, reflecting upon the Macedonian wars: “It was our way in those times in the midst of re- verses to wear the countenance of success, and in success to keep our souls within bounds.” Such were the qualities of gravitas. It was not merely turning a sober, serious, grave visage and aspect to life, but something much more deeply stirring and ennobling. A proconsul must present the stern face of authority to subject peoples as the administrator of Roman law and peace, but also he aspired to glory (gloria), immortal glory.

Glory has passed largely from modern life until the very expression has become empty of meaning, but to the Roman glory was the utmost exaltation to which the aspirations of man might attain. Here the pride in his land and his fathers, the fame of his own deeds, civic and military, the honor and renown accorded to him are emblazoned in that imperishable glory which found fitting expression in his own gravitas. Yet even gloria was conceived in essentially material terms and was recognized with monuments, inscriptions, and epitaphs. It reflected the same conceptions of immortality that led the Roman to seek a burial-place by the road-side or near the market-place so that the record and knowledge of him might be preserved in human memory. Glory was, for the most part, earthly fame and human honor.[24] Few Romans rose to the noble sentiment which Tacitus expressed for his beloved father-in-law, Agricola, in the closing words of that great biography:

To his daughter as to his wife, to the one as father, to the other as husband, I enjoin that his memory be reverenced, that they reflect upon all his words and deeds, that they embrace the form and figure of his spirit rather than of his body, not because I think we should dispense with effigies which are fashioned of marble and bronze, but because, like the very faces of men, so the likenesses of their faces are but weak and mortal, and because only the form of the mind is eternal which cannot be preserved in the materials of earth or expressed by the art of man, but can live on only in your own lives and deeds. Whatever we have loved and admired in Agricola remains and will remain in the hearts of men in eternal fame so long as time shall last, though many of old who preceded him have fallen into oblivion without glory and without renown: The name and fame of Agricola shall survive in time to come as it is told and written here.[25]

Perhaps this translation is a trifle bold and free, but it may reveal the shift in Roman outlook that appears in the first century of the Empire with the dawn of Christianity. Glory is becoming a spiritual attribute; yet it is not without significance that in the closing lines of the prayer addressed by the Son to the Father which recognizes the sovereignty of God we hear the words: Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory (regnum et potestas et gloria). These are Roman words whether translated into Latin from the Aramaic or the Greek or interpolated at a later date as some texts indicate, and the force of them is not apparent detached from their Roman background. We encounter that great transition in the history of ideas where we pass from the kingdom and the power and the glory of earthly Rome to the kingdom and the power and the glory of the city beyond the skies in the other world, from the authority of the proconsul to the majesty of God. And with this change in perspective emphasis is shifted from the sovereignty of the earthly state or res publica which was a “thing of the people” to the sovereignty of the Heavenly Kingdom which is the empire or regnum of God. However, to the old Roman citizen represented by Scipio in the dialogue of Cicero’s treatise, On the Republic, res publica is res populi, and a people is “no mere assembly of men brought together in any manner whatsoever, but an assemblage of many, associated by consent to law and by a community of interest.”[26] To the new Christian subject of the later Empire, the only true state is the regnum or realm of God whose dominion is a spiritual kingdom reaching into the hearts of men and commanding their full faith and allegiance. Patriotism ceases to be love of one’s native land, respect for law and civil order, and regard for the welfare of one’s fellow-citizens. Now it is transformed into deference and submission to the will of an almighty God which is transmitted to men in this life through the agency of the Visible Church, the imperfect counterpart of the perfect society that lies on the other side which the mystic vision of Bernard of Cluny tried vainly to describe:

Jerusalem the Golden, With milk and honey blest,

Beneath thy contemplation Sink heart and voice oppressed:I know not, O I know not, What social joys are there;

What radiancy of glory, What light beyond compare!And when I fain would sing them, My spirit fails and faints,

And vainly would it image The assembly of the Saints.[27]

With the Middle Ages a titanic struggle will arise out of men’s divided allegiance between Church and State in the political sphere, while in the regions of thought and spirit the breach will be completed between the antique man who strove for undying earthly glory and unending worldly fame and the mediaeval man who renounced the world for visions of the radiant timeless glory of God. There is even a change in the meaning of eternity itself. It ceases to be an endless duration of time in a succession of material events conceived in terms of human action and becomes one all-embracing, breathless moment without limit or restriction in which past, present, and future fuse in the divine unity beyond considerations of temporal or spatial dimension, beyond the mere capacity to retain the past as present in a totally present time-unity such as Bergson suggests by the conception of duree in our own day. It was the purpose of the Roman to rule the world, of the Mediaeval to find God. Said Hildebert of LeMans in those astonishing verses which undertake to describe God: “Over all things, under all things; outside all, inside all; all within but not included; all without but not excluded; above all but not raised over; beneath all but not set under; wholly above, presiding; wholly beneath, sustaining; wholly without, embracing: wholly within, filling.’[28] Here Infinity and Eternity are God.

II

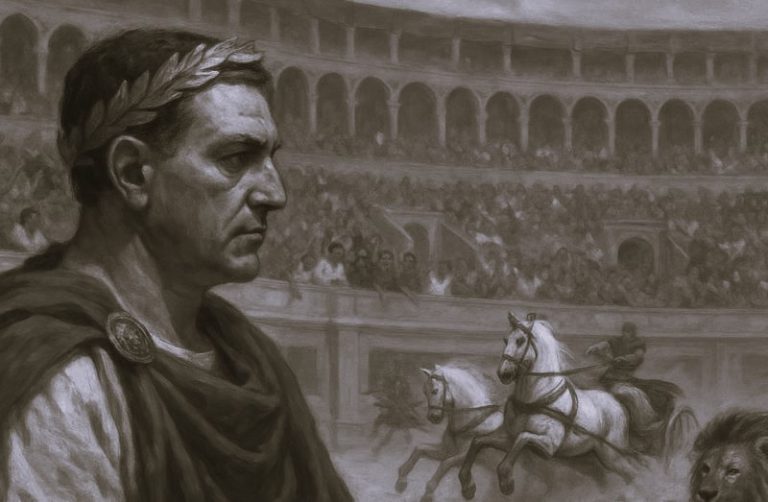

Lest we be accused of drawing an idealistic portrait of a man who had no ideals, it may be well for us to turn to the record of his person revealed by the monuments. I can recommend no more suitable illustration for this purpose than the splendid gallery of portraits contained in the Roman volume of the Phaidon Art Series, a great contribution to the history and appreciation of art made through the publication of the Oxford University Press.[29] In these Roman Portraits it is apparent immediately that there was no such man as the average Roman or the ideal Roman. The Romans were a highly individualized people differing widely in their physical appearance and presenting great variations in emotional quality and intellectual capacity. It would be a great mistake to suppose that the Romans con- formed to a common pattern. Not every Roman was a proconsul nor was gravitas stamped indelibly upon every face. There are administrators and public servants and immolators for the sacrificial rites whose features are characterized by all the austerity and sublimity of purpose that one associates with the noblest aspect of Roman character. There is the famous Copenhagen bust of an old lady who has the worn but determined countenance of the American pioneer mother. One feels that she has known hard work, hard times, suffering, and disappointment; yet an inherent kindliness of spirit and human sympathy shines through the tired and rugged outlines of her face, suggesting the solid strength of Grant Wood’s “American Gothic.” In general, one does perceive a certain heavy, massive, almost craggy impression of power recurring in the Roman statuary, combined with much unevenness of line and irregularity of feature. We may assume that it was only the more successful citizen whose genius could include a monument among his social insignia. Consequently the gallery must be filled with the likenesses of lawyers, businessmen such as traders (negotiatores) and tax-collectors (publicani),[30] officials of the civil service, military officers and engineers with their wives and children. Much of the sculptured record falls within the period of the last century of the Re- public and the first century or two of the Empire, and thus does not represent with certainty the Roman of the great days of the Punic wars. Greek influences and Oriental Slavery must have already done much toward the importation of urbane manners and sophisticated tastes which the maiores would not have approved. Roman conservatism yielded reluctantly to these foreign cultural elements. This was typified by the hostility of the elder Cat0 to the insidious Greek learning and the hateful remnants of Carthaginian political and economic power. Yet it is told of Cato, who is commonly depicted as a one hundred per cent Roman of the old school, that late in life, recognizing that changing times bring new habits and attitudes toward life, he began the study of Greek in the company of his grandsons. This must not be taken to mean, however, that Cat0 had come to accept the Greek cultural outlook. Cat0 was a practical Roman, devoted to the ancestors and the republic and to the old ways. Since a Roman proconsul must know Greek to administer a province filled with Greeks, one learned the Greek language in the same spirit of advantage and necessity with which he destroyed the city of Carthage.

Nevertheless the broad fact in the history of civilization remains true that the Greek poets and philosophers had begun their cultural conquest of their masters. It is also true that the ordinary Roman did not like the Greeks and Orientals, and, although racial fusion was beginning at the lower levels of society, the sort of man who enjoyed a statue may have remained predominantly Roman well into the first century of the Empire. This suggestion should be qualified by reference to a remark of the late Professor Tenney Frank of Johns Hopkins, an outstanding authority on the racial causes for the decline of Roman civilization, who has said that old Rome had ceased to exist by the end of the first century of the present era and added:

If Scipio could have risen in Domitian’s day to see his native city, he would have found stately marble temples and palaces in the place of huts, but the features of the new Romans would have amazed him. The crowd of the Forum would have resembled the populace he once saw at Pergamum and the senators would have differed little from the people on the streets. One has but to imagine the shade of Washington parading the Bowery.[31]

The tricky, facile Greek remained an object of distaste and dislike from Cat0 to Juvenal. The Roman distrusted his disingenuous, ingratiating smile and his flippant, facetious repartee. Greek levitas was utterly offensive to the Roman spirit of gravitas. Likewise, the Roman hated and despised the servile Orientals whom Juvenal denounced in his Third Satire:

Long since, the stream that wanton Syria laves

Has disembogued its filth in Tiber’s waves,

Its language, arts; o’erwhelmed us with the scum

Of Antioch’s streets, its minstrel, harp, and drum.

Hie to the Circus! ye who pant to prove

A barbarous mistress, an outlandish love;

Hie to the Circus! there in crowds they stand,

Tires on their head and timbrels in their hand.[32]

Despite his racial and cultural antipathies the Roman retained his gift of human understanding. There are smiling Roman faces, faces lit with humor and controlled amusement, and faces filled with the sadness of man’s mortality. There is the courage of the pagan world resigned to fate, but determined to carry on. There are young men eager to assume life’s burdens, not altogether weaned from the spirit of play-but there are no Greek athletes among them. Some women appear more competent than comely; others are pretty, possibly a bit silly. There is even the eternal freshman among them, a young lady named Minatia Polla, who has doubtless joined her literary society. And the Roman infant has the same speculative preoccupation – perhaps with his toes which we cannot see in his portrait- that has characterized all the babies of the world from the beginning of time. The Roman faces of the Phaidon gallery in their direct revealing frankness are filled with intrinsic humanity so that one feels he has met them all before in his own experience of life.

Whether or not one regards the notion of a Zeitgeist and a Volkgeist as the product of folk lore, imagination, or sheer superstition, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that in the life of every people and of every nation history presents as objective fact some brief period of time in which the native genius of a race displays its ideal qualities in a peculiarly intensified and impressive manner. To me this summit of Roman greatness emerges during the Second Punic War when the survival of the republic swayed in precarious balance. Similarly I seem to discern the highest pinnacle of the North American republic raised over the four terrible years of crisis in the Civil War during which the life energies of this people were concentrated in a unique degree. Therefore, it is to the Scipios, not to the Caesars, that we must look for our most ideal expression of the supreme traits of Roman character. Cicero realizes this truth when he turns to the soul of Scipio for a revelation of the political genius of Rome and a prophecy of her future greatness in that strange mystic vision of the De Re Publica which is known to letters as Scipio’s Dream (somnium Scipionis). It is Africanus rather than Augustus who establishes the criterion of the Roman genius.[33] Even Cat0 is a little late to represent the most perfect type of citizen, to say nothing of Cicero with his nostalgic yearning over the half-forgotten memories of a day that had passed. The power and glory of the republican heroes of the olden time was a very different thing from the pomp and circumstance of the deified emperors of the new order. When we view the veritable figures of history in the Phaidon gallery and attempt to discern in their visages the noblest traits of traditional Roman character, we are beset with several difficulties. They are men of the new time and bear the neoteric stamp; they may be represented in an idealized manner; and in many cases they may be the victims of false attribution. For many years a late bust of an anonymous priest of Isis was accepted as the likeness of Scipio. However, one feels that he faces the actual Cicero, and senses that this man had pride of soul and power of intellect, had known desolating failure and transient success, had glimpsed the glory briefly to which he aspired and which posterity has granted him. The bronze Caesar of the Museo Nazionale at Rome must be Caesar. Surely no man who has ever lived can have remotely resembled him. Such is the impression one derives as he studies the knit brows, the brooding melancholy, and the barest suggestion of a smile commingled of the irony of greatness and compassion for a subject world. The Capitoline Augustus suggests by its symmetry of feature and chilly aspect the selfless energy, driving purpose, and calm decision of the world’s greatest administrator and statesman, the founder of the Principate, who transformed the Republic into an Empire. Finally in the lengthening twilight that Rome spread across the centuries one falls beneath the enchantment of the youthful Marcus Aurelius. His face is already shaded among the purple shadows in that dusk of the pagan soul, prefigured by the great Latin elegists. In this ineffable face one is overcome by a sweet sorrow and gentle sadness, a delicate sentiment and fragile beauty, a reminiscence of past glory and wistful resignation to the present. Like notes of ghostly music re- ceding amid the deepening shades of antiquity’s evening never to return, one recalls the hopeless lines of Catullus:

The suns can westward sink again to rise

But we, extinguished once our tiny light,

Perforce shall slumber through one lasting night[34]

This is an Evening Face of Youth and not like anything else on earth. It was the Greek youth who showed to the world a bright and shining Morning Face. This youth of late Rome has much of the Vergilian mood of mortality that rises “from souls touched by the sadness of others’ lives,” for Henry Osborn Taylor has remarked with much beauty that it was Vergil who voiced the saddened grandeur of the pagan heart. “His nature held pity for life’s pitifulness, sympathy for its sadness, love for its loveliness, and proud hope for all the happiness and power that the imperial era had in store.” The final Vergilian feeling was real love and pity.[35] But this path carries us toward the Christian Middle Ages, and this mood has no common de- nominator with Scipio. In the meantime, the hope and anticipation of Vergil had been realized and already grown dim by the time of Aurelius. Still nearly all these faces re- veal in some measure those civic and social virtues cherished in an earlier day.

Among these authentic generic traits that distinguish the patriotic, public-spirited Roman statesman are humanitas and liberalitas.[36] Neither of these expressions mean precisely the same as our present concepts of humanity and liberality. Humanitas is not Renaissance humanism which represented a catholic interest in man and all his works turned to selfish purposes, nor is it modern humanitarianism with its sentimental kindness that occasionally defeats the better interests of its beneficiaries. Rather it is a constructively co-operative attitude of right regard and interest in all things human reflecting that detached consideration for others upon which genuine social understanding depends. Humanitas is the recognition of essential humanity and intrinsic human nature. Such an understanding perceives man for what he is and renders him his due, and in this respect is not far removed from justice; yet it involves also that inner feeling for humanity that senses human defects and allows for them. It is here that the spirit of human kindness and philanthropy enters the concept and opens the way for the Christian humanitarian love of man. Besides, humanitas touches the realm of art and taste, and connotes those elements of refinement and culture that mark the civilized man, something at once more genuine and less precious than the elegance and politeness that characterize urbanitas and the urbane man. And there has been a tend- ency to mistake urbanity for humanity. Similarly, liberalitas is not the public manifestation of generosity to win personal reputation and esteem that Machiavelli considers in his sixteenth chapter of The Prince, concerning liberality and meanness. It is not the selfish sort of liberality that is adopted from ulterior motives of policy, but the inherent nobility of character that enables one to give something of value to another and feel that by so doing he has contributed to his own spiritual enlargement. Closely related are the traits of benevolentia and dementia. Benevolence is really an aspect of humanity, agreeable to men whose minds are accustomed to law and justice. It reflects an ability to appreciate the human angle or equation, breadth of sympathy, and kindly regard for others. Benevolence is the trait of people who have the capacity to measure men, and includes a mental habit that inclines men to think well of the world in general. Clemency carries us beyond the realm of mere equity and implies a mercy beyond the strict and rigid requirements of law. It was a quality to be employed with discrimination but appreciated to the full among a nation of lawyers when applied with wisdom and moderation. Lastly we may observe modestia and magnificentia. The former includes much more than our narrow modern conception of modesty. It is, indeed, temperance, moderation, good practical judgment, especially in matters of taste and conduct. Like gravitas, it reflects an appearance one would exhibit before others, avoiding all boastfulness and extravagance of manner. But it must not be confused with Christian humility, for it is highly self-regarding despite its unassuming presence, respect for authority, and observance of custom. Again it is balance, proportion, “the golden mean’’ (aurea mediocritas) applied to conduct and manners. No trait is more specifically Roman than magnificence, but again the meaning turns on inner significance, not outer form and expression. Magnificence in the citizen and states- man was never dazzling display either of personal riches and adornment or of intellectual subtlety and profundity, but it was high-mindedness, loftiness of thought and character, splendor of mind, and grandeur of spiritual aspiration.

Indeed, the true greatness in the structure of the Roman soul consists in a kind of spiritual grandeur which one perceives rather than understands. However, after this some- what extended exploration of the intellectual and moral regions in which the great proconsul had his being, we realize that he belongs to an entirely different historical dimension than contemporary men of the modern world. Friedell had grasped the essential truth of the matter when he warned us that “pre-Christian peoples-let us not harbor any delusions about that-are in the ultimate depths of their soul unintelligible to us-and a hopeless gulf separates us from Antiquity.”[37] Consequently we see that the modern passion for drawing superficial parallels between our own time and the ancient world is a vacant and fruitless pastime.[38] Yet one is constantly posed with the query: How would the Roman and his civilization stand against the modern background? It may be answered that even if we accept the view that he lacked creative and inventive genius, which is far from proved, he had admittedly great native capacity for adaptation. On the military side the First and Second Punic Wars provided an arena and testing-ground of the human spirit that can sustain any comparison with the First and Second World Wars. These wars average in length twenty years each: First Punic 264-41 B.C.; Second Punic 218-201 B.C. They were the world wars of their day, fought on many fronts with immense destruction of life and property. At Cannae in 216 it is estimated that Hannibal slaughtered not less than fifty thousand men with an additional ten thousand taken prisoners, representing, with the missing, losses of some sixty-five thousand out of a total army numbering nearly eighty thousand men. These young men, the flower of Roman youth, were killed in hand- to-hand fighting-a heavy afternoon’s work even in this age of dive-bombers and machine-guns. It is a busy day on the Russian front before Stalingrad which reports five thousand Nazi casualties.[39] Yet report has it that during those terrible days when Hannibal stood within sight of the walls of Rome, the brokers in the Farum were bidding up the real-estate upon which the Carthaginian army was standing. In very truth, shattered by these grievous wounds Rome was compelled to contract her efforts until a new generation of heroes was ready to face the foe. Nonetheless,during these fateful years after Cannae (215-208 B.C.) the Romans managed to maintain successful sieges of Syracuse, Capua, and Tarentum, to ward off the treacherous stab-in-the-back of the Macedonian king known in history as the First Macedonian War, to conduct a protracted campaign in Spain, to hold off the terrific Hannibal himself in Italy, and to defeat at the Metaurus river the effort of Hasdrubal to effect a junction with Hannibal. To all this it will be replied that admittedly the Roman had surpassing gifts in the military art as practiced in his day, whereas our genius consists in scientific achievement. I shall not discuss the competence of the Romans as engineers and architects. The modern engineer and architect knows full well that competence, and its record is written across the face of the Mediterranean world in the ruins of forum and basilica, of arch and palace, of circus and theatre, of the forts of the limes, and of roads and aqueducts ofttimes still largely intact, all scattered from the frontiers of Scotland to the edge of the Sahara and from Spain to Syria. And I cannot forbear to repeat the question of a great classical scholar who once asked what modern man could truly believe that a mind of the acuteness and curiosity of a Cicero would not master, within the space of a few short months, the major advances in thought and the technique of living attained during the two thousand years that separate him from us. Barbarian Japanese fly airplanes and drive tanks. Is there reason to believe great, adventurous Caesar could not have learned these arts?

As for the fields of politics and law in which Rome made her supreme contribution, we have observed the characteristic governing institution of the Republic which has been defined as an “affair of the people,” but organized in an essentially representative manner, so that the conduct of affairs rested in the hands of men of prestige and proved ability. These were the men who constituted the Roman Senate, the embodiment of the patres or fathers, and the assemblage of kings which confounded the Greeks. Their constitutional position was vague and uncertain, and de- pended in the final test upon successful performance of their function of government, so that the British scholar Pelham has remarked aptly that “the Roman Senate forfeited its right to govern when it ceased to govern well.” Judged by these standards, the modern dictatorships would not have recommended themselves to the great proconsul. He would have scorned their cruel, selfish, tactless, arbitrary, unenlightened exercise of power that overbalances any inherent efficiency or mobility in action. No responsible Roman statesman would have based the cornerstone of his empire on the principle of injustice toward subject peoples. But I doubt also that modern democracies would have recommended themselves in all respects to the great proconsul. He would have rejected their sentimental popular politics and demagogic appeals, the grandstand cheer-leader methods of radio and cinema propaganda, and the often uninformed leadership with its false standards of value. No responsible Roman statesman would have been so pre-occupied with social reform that he neglected the national security. Lastly, greater than the Senate itself was the Law. Law was the true sovereign which guaranteed the rights of groups and of individuals and defined their duties and obligations to the State.[40] Law opposed the anarchy of the individual run wild which insists upon arbitrary right and in which liberty has become license. Similarly the great pro- consul would repudiate the socialistic doctrine of arbitrary unrestrained power in the State, and, again, he would repudiate the current paternalistic doctrine of advantages, benefits, and conveniences, commonly confused with democracy, in which it has become the function of the State to minister to the comforts of its citizens. The Law, not the State, was the citadel of Roman sovereignty. The Law of the Republic, as the more5 of the Fathers in an earlier day, was the fountain-head of Justice, and it was the purpose of a State to dispense Justice to its citizens. The Republic was a moral and legal State. The Law gave and the Law took away. The Roman citizen received benefits but he owed obligations, and the obligation was uppermost. If the modern American in his hour of trial will search his own heart in the light of Rome’s experience with her centuries of blood, sweat, and tears, he will give thanks for the avoidance of many of her errors but also he will find that there is still much to learn if he is to administer or help in the administration of a regenerated world under a true pax christiana wherein the brotherhood of man shall be realized after the present tragedy has been resolved. At his best the great proconsul had the power of government in supreme degree, and from his record of statecraft and books of Law he can still teach us much that will aid in the mastery of the political art if we but turn to him with the same desire of learning that inspired the Founding Fathers of our own great Republic.[41] It will be our first lesson to understand that without character and intelligence no people is fit to rule either itself or others, that no people can continue to entrust its government to the witless without disaster, and that no people can commit its national fortunes and destiny in safety to the applause of a single man. I shall close with a word from one of Britain’s great poets of empire who wrote when she flourished mightily upon the sea and upon the land. Lord Macaulay knew the great proconsul, as, indeed, the Nineteenth Century did far better than the Twentieth, and read his mind well when he sang in the Lays of Ancient Rome:

To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods?

Notes

- Vergil, Aeneid (ed. Mackail), vi, 847-853.

- Acts, xvii, 21.

- C. Foligno, Latin Thought During the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon, 1929), pp. 5-6.

- Observe the musical interpretation of ancient Roman moods by O. Respighi in his orchestral suite, The Pines of Rome (Fourth Movement-The Pines of the Appian Way).

- Grant Showerman, Eternal Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1924), I, 76. 19311, pp. 86-92.

- T. R. Glover, The World of the New Testament (New York: Macmillan.

- Cf. The Oxford Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1905), VI1 (Part I), 559-560, which discloses that the derivation of the modern English, patriot, patriotic, patriotism, is conjectural, although it entered into common use as recently as the 17th or 18th centuries. It may derive from the late Latin patriota in the Epktolae of St. Gregory and patrioficus in Cassiodorus or from the Greek, through the French patriote (15th century) (Rabelais, 16th century). However, it depends clearly on the common Indo-European stem.

- See E. Pollack, Der Majestatsgedanke im romischen Recht: Eine Studie auf dem Gabief des romischen Sfaatsrechtr (Leipzig, 1908), p. 25.

- Cicero, In Catilinam, i, 17: patria quae communis est parens omnium nostrum.

- See article by the author, entitled “The Idea of Majesty in Roman Political Thought,” in Essays in History and Political Theory in Honor of Charles Howard McElwain (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1936), pp. 168-198.

- See chapter on auctoritas in F. Schulz, Principles of Roman Law, trans. by M. Wolff (Oxford: Clarendon, 1936), pp. 164-188.

- J. S. Plumpe, “Roman Elements in Cicero’s Panegyric on the Legio Martia,” Classical Journal, XXXVI (1941), 275-289 ; W. H. Alexander, “De Imperio,” Classical Bulletin, XIV (1938), 41.

- On virtus, see Plumpe, Class. Jour., XXXVI (1941), 285-86. Cf. Sir R. W. Livingstone, Greek Ideals and Modern Life (Oxford: Clarendon, 1935), pp. 69-91, for correlative Greek conception.

- E. M. Hulme, Renaissance and Reformation, rev. ed. (New York: Century, 1922), p. 76, regards virtu as a perfection of the personality, the power to will, or “that which makes a man,” but suggests that the word is really untranslatable. It is the quality of the virtuoso who sets no limit on his desires or deeds. Cf. Cellini, Autobiography, l, xxx, who uses virtuosamente to denote genius, artistic ability, and masculine force.

- Lucilius, Satirarum reliquiae, 1, i-xiii, following the beautiful translation in Showerman, op. cit., I, 86-87.

- Plumpe regards fortitudo as an aspect of virtus rather than as a complementary quality as I have suggested.

- See T. R. Glover, 09. cit., pp. 88-89, who narrates this incident.

- See J. S. Plumpe, Class. Jour., XXXVI (1941), 284-85, on relation of prudentia and sapientia.

- Cf. John Jay Chapman, Lucian, Pluto and Greek Morals (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1931), p. 72.

- W. C. Greene, The Achievement of Greece (Cambridge: Harvard Uni- versity Press, 1924), pp. 214-15.

- Tenney Frank, Life and Literature in the Roman Republic [Sather Classical Lectures, Vol. VII] (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930), p. 65, remarks that “the theme of Roman gravitas has perhaps been overworked”; yet F. Schulz, op. d., p. 83, says “Gravitas and constantia are the cardinal virtues of the Romans.” Cf. Cicero, Pro Sestio, Ixvii, 141: nosin ea civitati nati, unde orta mihi gravitas et magnitudo animi videtur.

- 2See essay on “Philosophy” by J. Burnet in The Legacy of Greece (Oxford, Clarendon, 1923), pp. 75-77.

- The Roman concept of the genius involves many controverted questions. Some would identify it with spirit, numen, and others with the Greek Galpus. See T. R. Glover, The Conflict of Religions in the Early Roman Empire (London: Methuen, 1909), pp. 1G15, 99-101.

- For the emergence of the modern idea of Fame, see J. Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. by Middlemore (London: Harrap, 1929), pp. 151-162.

- Tacitus, Agricola, c. 46.

- Cicero, De Re Publica, i, 25: Est igitur, inquit Africanus, res publica res populi, populus autem non omnis hominurn coetus quoquo modo congrega- tus, sed coetus multitudinis iuris consensu et utilitatis communione sociatus.

- See Bernard of Cluny (Morlas, Morlaix), De Contemptu Mundi, lines 77-78, in Part VII, p, 15, of Hortus Conchus (Washington: St. Albans Press, 1936).

- Cf. Henry Adams, Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres (Boston: Houghton MiWin, 1936), pp. 282-83.

- See Roman Portraits [Phaidon Edition] (New York: Oxford University Press, n.d.), especially plates 2, 4, 14, IS, 24, 28, 31, 51, 55, 58, 61, 63 (male types), 33, 38, 44, 46, 52, 53 (female types), 1, 68 (priest and priestess), 7 (Cicero), 8, 9 (Porzia and Cato), 10 (Copenhagen), 11 (boy), 21 (girl), 17 (Caesar), 22 (Augustus), 47 (Minatia Polla), 64 (baby), 66 (Marcus Aurelius).

- Grant Showerman, op. cit., I, 101, 105.

- Tenney Frank, A History of Rome (New York: Holt, 1923), p. 464. Quoted by permission of Henry Holt and Co. Also see G. Showerman, op. cit., I, 136-141.

- Juvenal, Saturae (trans. by Gifford), lines 99-106.

- E. M. Sanford, The Mediterranean World in Ancient Times (New York: Ronald, 1939), p. 345: “Of all Roman generals of the Republican period, Scipio was most like Alexander in his military genius and in his conviction of his own great destiny. Yet like the other members of his notable family, he made no attempt to substitute his personal power for the authority of the Roman Senate and people, though his exploits won him the title of Maximus.” Quoted by permission of the The Ronald Press.

- Catullus, Carminu (trans. by Burton), v, 4-6.

- Henry Osborn Taylor, The Classical Heritage of the Middle Ages (New York: Macmillan, 1929), p. 29. Cf. W. C. Greene, The Achiewement of Rome (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933), pp. 353-55.

- For humanitas and related concepts, see F. Schulz, op. cit., pp. 189-222.

- Egon Friedell, A Cultural History of the Modern Age (New York: Knopf, 1931), 11, 343-44.

- Historical parallels are often analogies which may corroborate in association with other demonstrable facts but are indecisive or misleading when considered in isolation. For a conservative and interesting use of this sort of evidence, see H. J. Haskell, The New Deal in Old Rome (New York: Knopf, 1939).

- These statistics are based on M. L. W. Laistner, A Survey of Ancient History (New York: Heath, 1929), p. 404, whose scholarship is notably accurate. At the Trebia river only 10,000 out of 40,000 Romans escaped, and at Lake Trasimene not more than 10,000 out of 35,000 returned to Rome (Laistner, pp. 402403). On September 24, 1942, the 31st day of the battle before Stalingrad, the United Press reported that the Germans had lost more than 5,000 men in the preceding three days in what it designated “one of the bloodiest engagements in history,” and on October 5th, the 42nd day of the battle, Moscow dispatches reported that “the Russians were killing more than 4,000 Germans a day.” On October 5th, the 46th day, the United Press again reported 4,000 Nazis killed in “the record blood sacrifice in one of history’s greatest battles.” On October 19th, the 56th day, a Soviet communique reported 2,500 Nazis killed in frontal assaults on the city, and on October 25th, the 61st day, 10,000 Nazis killed in two days, while on October 31st, the 67th day, Prawda is quoted as asserting that the Germans were losing 4,000-5,000 killed daily with as much as an entire division of 15,000 men sometimes killed or wounded in 24 hours. These statistics indicate average losses in killed of 2,500 to 5,000 per day in the German assaults upon Stalingrad, bearing out the estimates of military experts that the Nazis suffered casualties of 150,000 killed within two months in the siege of the city. C. J. Hayes, A Brief History of the Great War (New York: Macmillan, 1920), p. 155, states that probably 300,000 German soldiers must be numbered as killed, wounded or captured in the battles before Verdun between February and July, 1916. According to official reports, at Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863, the Union loss was 3,072 killed, 14,497 wounded, and 5,434 missing-an aggregate loss of 23,003 out of about 88,000 effective men: the Confederate loss was 2,592 killed, 12,709 wounded, and 5,150 missing-an aggregate loss of 20,451 out of about 73,000 effective men. Capt. B. H. Liddell Hart, The Real War, 1914 to 1918 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1930), p. 214, observes that time in the military sense has been trans- formed in modern warfare, so that battles now extend over periods of weeks and even months whereas in earlier times they lasted only a matter of hours or days. Likewise, I would add that space in the military sense has been extended, so that battles are no longer identified with specific localities or limited natural features but have become battles of nations and even continents. Indeed, a series of military operations, once called campaigns, are now designated battles. Military perspective, temporal and spatial, has changed. Nevertheless, the statistics do not seem to reveal a necessarily greater destruction in modern warfare but fundamental changes in the circumstances and processes of destruction, indicating a probably higher destructive potentiality. Comparisons cannot be made in the absolute but are relative to the established conditions of a given time.

- See C. H. McIlwain, The Growth of Political Thought in the West (New York: Macmillan, 1932), p. 111, who notes that a true republic must exist under bond of law (vinculum iuris) and cannot be under the domination of the multitude (the mass-man of Ralph Adams Cram), unless re- strained by consent to law, because such a multitude may be “as much a tyrant as if it were one man, and even more horrid.” This view is based on Scipio’s definition of a republic in Cicero, De Re Publica, iii, 31-33. Also in De Re Publica, iii, 22, Cicero defines further that “True law is right reason consonant with nature, diffused among all men, constant, eternal.”

- For classical influences upon American republican institutions, see G. Chinard, “Polybius and the American Constitution,” Journal of the History of Ideas, I (1940), 38-58.

Published by the Rice Digital Scholarship Archive under an open access license, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.