Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

The Patriots

“Patriots,” as they came to be known, were members of the 13 British colonies who rebelled against British control during the American Revolution, supporting instead the U.S. Continental Congress. These Patriots rejected the lack of representation of colonists in the British Parliament and the imposition of British taxes.

Following the French and Indian War (1753–1763), the colonies gained much greater independence due to salutary neglect, which was the British policy of allowing the colonies to violate strict trade restrictions to encourage economic growth. During the Revolutionary War, Patriots sought to gain formal acknowledgment of this policy through independence. Confident that independence lay ahead, Patriots alienated many fellow colonists by resorting to violence against tax collectors and pressuring others to declare a position in this conflict.

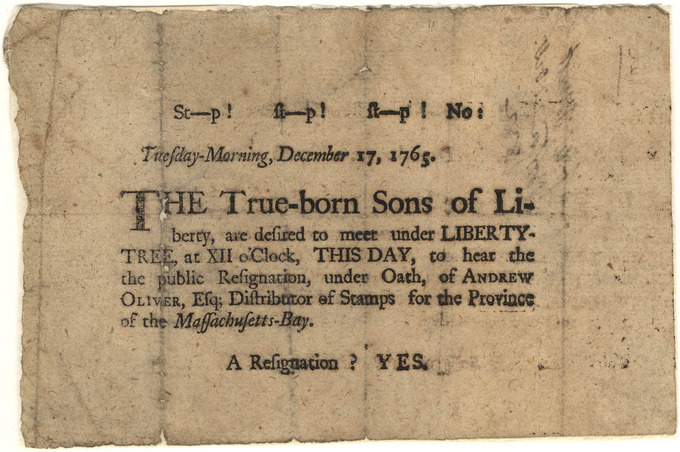

Prominent early Patriots include Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and George Washington. These men were the architects of the early Republic and the Constitution of the United States, and are counted among the Founding Fathers. Prior to 1775, many of these Patriots were active in the Sons of Liberty, an organization formed to protect the rights of the colonists from usurpation by the British government. They are best known for initiating the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

The Patriot rebellion was based on the political philosophy of republicanism as expressed by the leading public figures of the time, including the Founding Fathers and Thomas Paine, author of the popular pro-revolutionary pamphlet “Common Sense.” The philosophy of republicanism entailed a rejection of monarchy and aristocracy and emphasized civic virtue. Patriots were also known as American Whigs, Revolutionaries, Congress-Men, and Rebels. Though not all colonists supported violent rebellion, historians estimate that approximately 45 percent of the white population supported the Patriots’ cause or identified as Patriots; 15–20 percent favored the British Crown; and the remainder of the population chose not to take a vocal position in the conflict. Ultimately, Americans remained Loyalists or joined the Patriot cause based on which side they thought would best promote their interests. Prominent merchants in port cities and men with business or family ties to the elite class in Great Britain tended to remain loyal to the Crown, whereas Patriots were comprised largely of yeoman farmers. Nonetheless, people of all socioeconomic statuses populated both sides of the conflict.

The Loyalists

Loyalists, also known as Tories or Royalists, were American colonists who supported the British monarchy during the American Revolutionary War. During the war, British strategy relied heavily upon the misguided belief that the Loyalist community could be mobilized into Loyalist regiments. Expectations for support were never fully met. In all, about 50,000 Loyalists served as soldiers or militia in the British forces, 19,000 Loyalists were enrolled on a regular army status, and 15,000 Loyalist soldiers and militia came from the Loyalist stronghold of New York.

There was not unanimous support among members of the 13 colonies for the Patriot Siege of Boston (April 19, 1775–March 17, 1776). Widespread corruption among local authorities, many who later became Revolutionary leaders, alienated colonists from the Patriot cause. Colonists in New York, New Jersey, and parts of North and South Carolina were ambivalent about the revolution. Historians estimate that between 15 and 20 percent of European-American colonists supported the Crown; some historians estimate that as much as one third of the population was sympathetic to the British, if not vocally.

Americans either remained Loyalists or joined the Patriot cause based on which side they thought would best promote their interests. Prominent merchants in port cities and men with business or family ties to elites in Great Britain tended to favor the Loyalist cause. Nonetheless, people from all socioeconomic backgrounds could be found on both sides.

Loyalism was particularly strong in the Province of Quebec. Although some Canadians took up arms in support of the Patriots, the majority remained loyal to the King. Slaves also contributed to the Loyalist cause, swayed by the promise of freedom following the war. A total of 12,000 African Americans served with the British from 1775 to 1783. The Patriots mirrored this tactic by offering freedom to slaves serving in the Continental Army. Following the war, both sides often reneged on these promises of freedom.

By July 4, 1776, Patriots controlled most of the territory within the 13 colonies and had expelled all royal officials. Colonists who openly proclaimed their loyalty to the Crown were driven from their communities. Loyalists frequently went underground and covertly offered aid to the British. New York City and Long Island were the British military and political bases of operations in North America from 1776 to 1783 and maintained a large concentration of Loyalists, many of whom were refugees from other states.

In limited areas where the British had a strong military presence, Loyalists remained in power. For example, during early 1775 in the South Carolina backcountry, Loyalist recruitment outpaced that of the Patriots. Also, from 1779 to 1782, a Loyalist civilian government was re established in coastal Georgia.

When the Loyalist cause was defeated, however, many Loyalists fled to Britain, Canada, Nova Scotia, and other parts of the British Empire. The departure of royal officials, rich merchants, and landed gentry destroyed the hierarchical networks that thrived in the colonies. Key members of the elite families that owned and controlled much of the commerce and industry in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston left the United States, undermining the cohesion of the old upper class and transforming the social structure of the colonies. The Loyalist exodus also included Ohio Valley farmers who had relied on British military security against Pontiac ‘s armies. Recent non-Anglophone immigrants (especially Germans and Dutch), uncertain of their fate under the new regime, also fled. African American slaves and much of the Mohawk Nation joined the Loyalist migration north and northeast.

Slavery during the Revolution

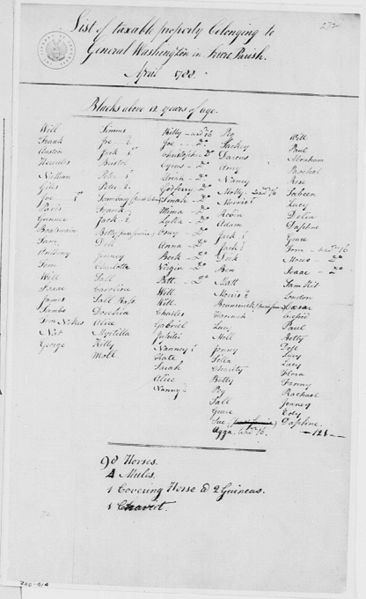

African Americans—slave and free—served on both sides during the Revolutionary War. Many African Americans viewed the American Revolution as an opportunity to fight for their own liberty and freedom from slavery. The British recruited slaves belonging to Patriot masters and promised freedom to those who served.

In fact, Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in United States history. Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, issued a proclamation offering freedom to all slaves who would fight for the British during the Revolutionary War. Hundreds of slaves escaped to join Dunmore and the British Army. Five hundred such former slaves from Virginia formed Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, which is most likely the first black regiment to ever serve for the British crown. African Americans also served extensively on British vessels and were considered more willing and able than their British counterparts on the deck.

Other revolutionary leaders, however, were hesitant to utilize African Americans in their armed forces due to a fear that armed slaves would rise against them. For instance, in May 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety stopped the enlistment of slaves in colonial armies. The action was then adopted by the Continental Congress when it took over Patriot forces to form the Continental Army. George Washington issued an order to recruiters in July 1775, ordering them not to enroll “any deserter from the Ministerial army, nor any stroller, negro or vagabond.” This order, however, was eventually reneged when manpower shortages forced the Continental Army to diversify their ranks.

George Washington lifted the ban on black enlistment in the Continental Army in January 1776, in response to a need to fill manpower shortages in America’s fledgling army and navy. Many African Americans, believing that the Patriot cause would one day result in an expansion of their own civil rights and even the abolition of slavery, had already joined militia regiments at the beginning of the war. Recruitment to the Continental Army following the lifted ban on black enlistment was equally positive, despite remaining concerns from officers, particularly in the South. Small all-black units were formed in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and many slaves were promised freedom for serving. African Americans piloted vessels, handled ammunition, and even served as pilots in various state navies. Some African Americans were captured from the Royal Navy and used by Patriots on their vessels. Another all-black unit came from Haiti with French forces. At least 5,000 black soldiers fought for the Revolutionary cause. Many former slaves who were promised freedom in exchange for their service in the Continental Army, however, were eventually returned to slavery.

Tens of thousands of slaves escaped during the war and joined British lines; others simply escaped on their own to freedom without fighting. Many who escaped were later enslaved again. This greatly disrupted plantation production during and after the war. When they withdrew their forces from Savannah and Charleston, the British also evacuated 10,000 slaves, now freedmen. Altogether, the British were estimated to have evacuated nearly 20,000 freedmen (including families) with other Loyalists and their troops at the end of the war. More than 3,000 freedmen were resettled in Nova Scotia while others were transported to the West Indies of the Caribbean islands. Others traveled to Great Britain. Many African Americans who left with Loyalists for Jamaica or St. Augustine after the war never gained their freedom.

American Indians and the Revolution

During the American Revolution, the newly proclaimed United States competed with the British for the allegiance of American Indian nations east of the Mississippi River. Most American Indians who joined the struggle sided with the British, based both on their trading relationships and hopes that colonial defeat would result in a halt to further colonial expansion onto American Indian land. Other native communities were divided over which side to support in the war and others wanted to remain neutral. The first American Indian community to sign a treaty with the new United States government was the Lenape. For the Iroquois Confederacy, based in New York, the American Revolution resulted in civil war. The only Iroquois tribes to ally with the colonials were the Oneida and Tuscarora.

Frontier warfare during the American Revolution was particularly brutal and numerous atrocities were committed by settlers and native tribes alike. Noncombatants suffered greatly during the war. Military expeditions on each side destroyed villages and food supplies to reduce the ability of people to fight, as in the frequent raids by both sides in the Mohawk Valley and western New York. The largest of these expeditions was the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, in which American colonial troops destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages to neutralize Iroquois raids in upstate New York. The expedition failed to have the desired effect, as American Indian activity became even more determined.

The British made peace with the Americans in the Treaty of Paris (1783), through which they ceded vast American Indian territories to the United States without informing or consulting with the American Indians. The Northwest Indian War was led by American Indian tribes trying to repulse American colonists. The United States initially treated the American Indians, who had fought as allies with the British as a conquered people who had lost their lands. Although most members of the Iroquois tribes went to Canada with the Loyalists, others tried to stay in New York and western territories to maintain their lands. The state of New York made a separate treaty with Iroquois nations and put up for sale 5 million acres of land that had previously been their territories. The state established small reservations in western New York for the remnant peoples.

By P. Scott Corbett, et.al., provided by OpenStax College, published by Lumen Learning under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.