Peasant consumption extended beyond the village.

By Dr. Phillipp R. Schofield

Professor of History

Aberystwyth University

Introduction

Medieval historians are increasingly interested in low-level exchange, peasant economic agency and the significance of peasant production and consumption not only in terms of standard of living but also as motors of the wider medieval economy. This also means that historical discussion of the medieval peasantry has tended to locate peasants in a wider world than once was the case. Where once the historical focus was upon the relations of lord and tenant, defined by rent and labour within the confines of the manor, peasants and other rural-dwellers are discussed in ways that show them as acted upon by other than simply their lords: the church, government, merchants, townsmen, all had a significant if not always consistent part to play in the lives and economy of the medieval village. As importantly, and as some historians to date have tried to show, the peasantry’s reach, in terms of production for wider markets and of consumption within those same markets, also had an impact that, cumulatively, was of the greatest significance. Chris Dyer and the late Richard Britnell have both shown that peasant consumption extended beyond the village and that small-scale exchange between trade town and countryside was of the greatest significance to the medieval economy.1 In a number of studies in the last two decades or so, other historians have tested the likely contribution of peasants, c.1300, to England’s GDP and have concluded that it was vast.2 Within the medieval village historians have also tended to view the nature of exchange differently; whereas it was once a standard that much inter-peasant exchange was a function of familial and seigneurial relations and that, to quote M. M. Postan, the former of these were often characterized by a certain ‘timelessness’, a histoire immobile has tended to give way to a rather more frenetic village-level economy where (certainly in the eastern counties and in the decades either side of 1300 – where a fair amount of recent research has been focused) exchange, especially the buying and selling of land, moved at a pace determined more by prevailing market conditions than by the life-cycles of peasant families.3 As Bruce Campbell noted in an article published almost a decade ago, this also served to redistribute and to help fragment holdings in ways that left small-holders dependent upon fragile markets and highly vulnerable to the kinds of severe price hikes occasioned by poor and sometimes disastrous harvests.4

This essay will explore the ways in which capital in the form of credit and goods came into and, most importantly, was extracted from the medieval village in the decades either side of 1300, and consider especially the role of external creditors, including merchants, in that process. This is a topic that has been little studied by historians to date and those historians of the medieval English village who have addressed issues of credit and indebtedness have tended not to give it a great deal of attention. In what follows, the suggestion is that, while the number of smaller-scale credit and trading agreements internal to the medieval village was almost certainly greater than the more extensive credit agreements that took place in the medieval village, the extent of even a few much larger agreements, often established beyond the manor and village between unequal parties, was of far greater weight and significance than the cumulative totals of the smaller-scale agreements. From this basis it is argued that such large agreements illustrate the economically rarefied position that creditors (including merchants and factors from beyond the village) and their debtors (mostly upper- and middling-type villagers) may have occupied in the medieval rural economy; it is also suggested that the largest credit agreements could and did sometimes operate in direct response to, but also on occasion independently of, the major and more familiar economic and environmental crises, including harvest failure, which historians associate with this period and identify as the main drivers of economic and social change.5 It is also suggested that the behaviour of such agreements, as typically recorded in the form of pleas of debt in manorial courts, which may not have followed a consistent pattern but instead responded to the needs of the parties to the particular agreements, could have significant secondary effects within the locales of the debtors, not least in their impact upon the capacity of the wealthier villagers, debtors to outside creditors, to engage with and support their poorer neighbours during periods of shortfall and crisis.

Debt

Overview

A good deal of discussion of economic activity within the medieval village has centred upon relations between lord and tenant and, to a lesser but also significant extent, of dealing between villagers. Thus, as well as a persistent commitment to discussion of such issues as rent and labour service, there has also been a good deal of work, especially in the last quarter century or so, on inter-peasant exchange, especially in terms of land, and most recently, goods and credit.6 In the last decade or so, work by Chris Briggs as well as my own work has sought to deepen and extend the limited extent of research on rural credit.7 Most of this discussion of credit has been directed at inter-personal litigation within the manor court and within the village, i.e. peasants arranging credit agreements or suing each other in debt. There has been much less discussion of credit issuing from beyond the manor and village or being extended and/or recovered by individuals who dealt not only with peasants.8 As Jim Bolton has noted, ‘we know little about how and from whom money could be borrowed in villages’.9 Chris Briggs suggests that credit was sustained horizontally in the medieval village and that transactions were often, indeed, typically, conducted between parties of roughly equal standing, both parties tending to come from within rather than beyond the villages. Briggs does however note that a small number of villagers appeared to sit outside this general pattern, appearing more often than most as creditors and seldom, if at all, as debtors.10 As well as attempting to identify the nature of relationships between parties, of which more below, close examination of the pleas encourages a number of conclusions regarding the timing of the litigation, the period of the initial contract and of the subsequent recovery, and of the tactics of both creditor and debtor in a changing economic landscape. And, importantly, the economy, as we have already mentioned in terms of grain price movement, changed often and quite violently in this period, that is, the decades either side of 1300. As Briggs and others have described, a count of surviving litigation permits some reasonable quantification of the extent and fluctuation in litigation over debt.11

While a large number of such debt cases recorded in manorial courts from the thirteenth century appear there in summary fashion, some cases provide a good amount of detail and offer particular insights into the nature and significance of credit and its withdrawal in this period. Debt cases in the form of detinue, where the defendant has detained a debt beyond the term of the original agreement, often include details of original terms and, as will be discussed, offer particularly useful insights. Briggs identified a handful in his case-study manors and an examination of the dataset for the AHRC-funded project on personal litigation in manorial courts suggests there are a number of such instances.12 The following example, from East and West Hanningfield in Essex (1332), presents one fairly typical instance in order to set out the general features of such pleas:

Henry Fulk was attached to respond to John de Mattere of Borham who claimed that the same Henry unjustly [detained] from him 11s which he handed to him on Sunday after the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary 1 Edward III (8 February 1327) in the vill of Borham to pay to the abovesaid John on Sunday after the middle of Lent next following (15 March 1327), at which date he did not pay to the said John but detained and to this point detains to John’s damage of half a mark and thus he offers his suit. And the abovesaid Henry comes and denies the debt as pleaded and so is at law.13

It will be useful to itemize important points that emerge from entries such as this one.

Delayed Payment beyond Initial Term

In the first instance, it is clear that examples such as Mattere v. Fulk illustrate the ways in which terms could be extended, de facto if not de iure. To offer some further general instances, in Mildenhall (Suffolk) in January 1285, for instance, there are a number of debet and detinet-type pleas relating to various sale agreements and deferred payments where the defendant/debtor had failed to pay within the agreed period. The initial period given at Mildenhall was often less than a year but it is striking that the plaintiffs sometimes waited substantially longer than this (sometimes three to five years) before seeking to recover their loss plus damages.14 At Heacham, Norfolk, in December 1289, the plaintiff Agnes de Rudham sought recovery of 19s 6d in silver (argentum) owed for the purchase of three quarters of brewing barley, valued at 6s 6d per quarter, the purchase made over five years earlier in June 1284.15 Similarly, at Great Barton, Suffolk, one plaintiff, William Raysun, allowed the substantial debt of 37s 7½d, owed to him by John le Forster, to run on for almost five years beyond its original term.16 At Hinderclay, in the early fourteenth century, recovery of outstanding debts in the same form suggest that creditors were sometimes prepared to tolerate even longer periods, on occasion more than a decade, before (typically though not always in difficult, i.e. high grain price, years) they sought to enforce repayment. A return will be made to some of these examples later, as well as to the more general observation regarding delayed recovery of the debt.17

Size

Striking in terms of debts recorded as detained in the form ‘debet et detinet’ or ‘detinet’ is the information provided on size; it is perhaps not surprising that debts pursued to judgment or for which clear repayment dates had been fixed in the presence of witnesses or supported by written instrument were often relatively large but an initial sampling of debts recorded as unjust detentions suggests that at least 50 per cent were worth more than 5s, and some of these were worth substantially more; it is possible that the longer the term of the debt, then often the larger the size of the debt.

I have tried to suggest elsewhere that most debt cases in manorial courts reflect, even there, relatively substantial credit agreements and their recovery as debts. Of course, it is entirely reasonable to suggest, and indeed it is supported by the evidence, that a great deal of small-scale lending and borrowing took place in the village. It is also reasonable to assume that a high proportion of that did not find its way into the manor court, possibly because (i) the size of the agreements was too small to justify the involved costs or the involvement of the court and (ii) most such agreements could be resolved extra-curially in any case. Our view of the credit ‘market’ in the medieval village must not though be dominated by smaller debts: larger debts (say, of 5s and above) were an important and discrete element in the credit ‘market’ of the medieval village, at least c.1300, and it is quite possible to conceive of higher-level credit being more typically dealt with in the manor court.

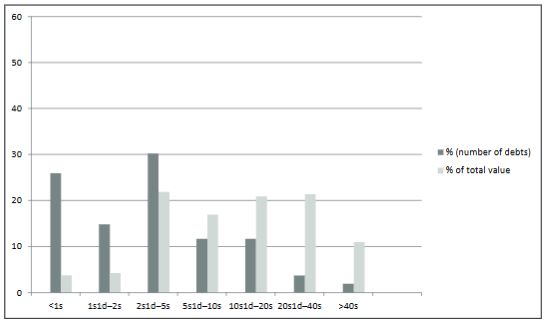

A focus upon some of the larger debts, some clearly issuing from beyond the manor and involving individuals who we might reasonably identify as merchants, suggests that the total amount of money or money equivalent loaned in the form of small debts and subsequently recovered in the manor was really quite insignificant relative to the money-value of individual larger debts. By my estimate, debts of 1s or less accounted for no more than 3.74 per cent of the total sterling value of credit lent and subsequently pursued as debt at Oakington, Dry Drayton and Cottenham between 1291 and 1350.18

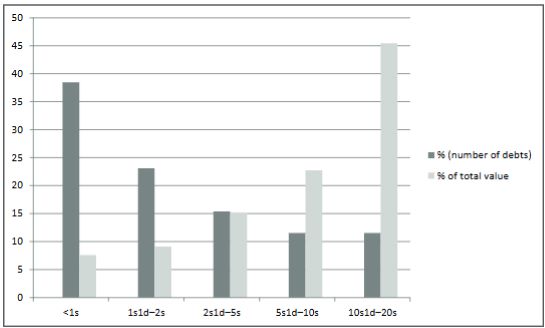

The total value of debts worth 5s or less was, by estimation, less than 15 per cent while debts to the individual value of 10s or more accounted for upwards of 70 per cent of the total value loaned on the three manors (Table 13.1). Using a smaller sample, of a decade for Hinderclay (Suffolk), from 1311–20, similar patterns emerge: here over 38 per cent of debts with size recorded were for 1s or less. Their overall value as credit, relative to the total recorded credit visible in the court rolls in this period, was again much smaller, at 7.6 per cent. Debts of more than 5s accounted for 23 per cent of credit transactions but over 68 per cent of the available credit (in litigation) (Table 13.2).

Proof

It is also worth noting that some of these larger debts, especially the largest (i.e. 20s or more) were secured by written instruments of a kind that were clearly far from typical in everyday dealing at the village level. While manorial officers would have been closely familiar with tallies and other written/semi-written forms of proof, it is also evident that most dealing in credit at the village level (rather than at the manorial level) was conducted orally and supported by witness proof, as in the example of Mattere v. Fulk given above. However, such reliance on oral proof was not always the case and we most obviously encounter tallies, tallies under seals and other forms of written instrument in ‘business’-scale transactions, sometimes conducted at arm’s length, that is with the plaintiff operating from beyond the manor or village and perhaps (sometimes) explicitly applying mercantile law, lex mercatoria. At Horsham St. Faith (Norfolk), on the day after the feast of St. Faith (7 October) 1311, a plaintiff-creditor was able to prove his debt of 20s 3d in a contract involving the sale of iron at Norwich by proof of tally secundum legem mercatorum.19 We will return to other examples later in this essay.

Where written proof did not exist, litigants tended to employ inquest jury or, in debt, more often, as we have just seen in the example above, wager of law. In such instances, where written proof was not available, the length of time subsequent to any breach of the original agreement and before the plaintiff sought recovery may, of necessity, have been shorter than if the plaintiff was dealing under merchant law and employing tally or other written instrument; that said, even over relatively short periods and where written proof could not be vouched, it was possible for the defendant to deny details of the contract to his or her advantage. At Heacham, on 6 February 1299, a defendant, Roger Tucben, sought to retain 4s 6d which the plaintiff, William Attepit, claimed as the remainder of the original purchase price for three quarters of barley purchased by the defendant two years previously. Tucben had already paid 8s 9d for the barley but the plaintiff, Attepit, claimed that the original agreed price had been higher, at 13s 3d.20 This, the defendant denied. Confronted with written proof under mercantile law, most defendants had however no defence and did not typically pursue one. The example from Heacham (1289), given earlier, is unusual in that the defendants in that plea of unjust detention sought to reject the plaintiff’s claim for three quarters of barley, denying the contract and the tally and seeking compurgation instead.21

External Creditor-Plaintiffs

Perhaps most importantly, the kinds of trading and business and legal practices employed in these instances also conform to the view that at least some and perhaps many of such creditors identified in agreements of this kind were not residents of the manor in which they were observed to be pleading, and that they had entered the court solely to pursue a particular debt/debtor. Such extra-village/manorial dealing is not always easy to detect and may involve a degree of close investigation of debt litigation but also some prosopographical investigation of parties to litigation. Elsewhere, this essay examines the presence and role of external creditors in the manor court c.1300 and others have also speculated about the role of Jewish lenders in the mid-to-late thirteenth century and clerical lenders in the same and later periods.22 It is a noticeable feature of the more significant plaintiffs, those pursuing large sums, and often supported in their plea by written instrument, that they appeared hardly at all in the particular manor court in which they were found as plaintiff. This is generally supported by the further analysis of the individuals involved: plaintiffs, sometimes referred to as ‘x of y’ – as in the example given earlier – and seldom appearing elsewhere in the records of the local court, standing in contrast to debtors who were often very familiar figures within the particular local court. We cannot say with certainty that all of these external creditors were merchants or factors from further afield but it is reasonable to suppose that some were. For instance,

John Bande (‘Baude’) of Ipswich appeared in the manor court at Walsham-le-Willows (Suffolk), in December 1321; an Ipswich resident, Baude was closely involved in the town’s government and paid the sixth highest (out of 210 payments) in the 1327 lay subsidy for Ipswich. At Walsham-le-Willows, Baude pursued William Wodebite, a villein of the manor of Walsham, in a plea of debt. William was attached to respond to John. The jurors of the manor court agreed with John that he had delivered 12 marks of silver (£8) to William, in 1319, at Ipswich ‘to trade and profit for John’s benefit, and William was required to render faithfully a true account thereof quarterly, in accordance with the law merchant and by a certain written agreement’. It transpired that William had refused on numerous previous occasions to render his account and had continued to withhold the debt ‘and the profits therefrom’. It was ordered therefore that John should recover.23 This was John Baude’s only appearance in the Walsham-le-Willows court rolls; similar instances of ‘single-entry’ plaintiffs can be found in other series of courts.24 Such plaintiffs were non-resident and, it is reasonable to assume, had attended the court solely to pursue their debtor and beard him or her in his den.

Credit Agreements

Overview

Examples such as this suggest that credit and debt relations at the level of the manor and village included, by c.1300, credit agreements originating beyond the manor and that, contrary to what is sometimes suggested from creditor-debtor relations in the medieval village and certainly in terms of the proportion of capital involved in the larger credit agreements, we cannot see credit in the manor as largely explained by reciprocal indebtedness operating between generally equal parties.25 This has a number of potentially significant implications for our understanding of the operation of credit and the availability of capital in the medieval village, c.1300, and in particular raises the issues considered in the remainder of this essay.

Business-Type Credit Agreements

Briggs has suggested, from his analysis of litigation in seven manorial courts, that there is no significant difference between the pool of creditors and that of debtors: ‘in no village did there exist a small clique of repeat lenders catering for a much larger set of borrowers’, a feature he rightly recognizes stands in contrast to much that is known about credit markets in other medieval European contexts.26 This is also contrary to what we might expect if we apply our understanding of typical selection bias from later periods to the socio-economic composition of litigants in the medieval manor court; in different periods and courts, we might tend to suspect that relatively wealthy litigants were frequent users of litigation in ways that other of their neighbours may not have been.27 Other analyses conducted to date also seem to suggest that Brigg’s pattern may not be universally applied to the medieval village. At Hinderclay, for example, between c.1290 and c.1305, two villagers were involved as parties in over 30 per cent of the recorded litigation in the manor, 7.25 per cent occurring between the two of them.28

It is also evidently the case that, on occasion, single and uniquely wealthy or well-placed individuals could dominate debt litigation in manorial courts, sometimes for quite discrete periods of time and often no doubt for rather particular reasons. It is the withdrawal or recovery of the larger loans by such individuals, doubtless encouraged in most instances by higher grain prices, that should, if only in terms of the relative weight of their capital, demand our attention. Recovery during a period of high prices does not necessarily suggest that creditor-plaintiffs were in all instances impecunious; we know, for instance, that creditors and grain dealers allowed debts in grain to persist until prices were high and then sought recovery (something that is consistent with mercantile usage in grain marketing in the same period and offered a reasonably effective device for speculating on the returns from the initial contract).29

It is possible, for instance, to consider a number of related claims based on debt and unjust detention, issuing from the same plaintiff, and which appear to reflect the breakdown of normal business relations at the village level and the imposition of aggressive trading on the part of factors, the latter quite possibly occasioned by the external factor of harvest failure. At Great Barton (Suffolk) on 17 March 1316, in the first year of the Great Famine, it was found that Alex Raysun, most probably a manorial officer, had unjustly

detained one quarter of wheat (worth 16s), one and a half quarters of rye (worth 21s), and four bushels of oats worth 5s from a Stephen de Haukedon (mod. Hawkedon). De Haukedon, who may be the same Stephen de Haukedon who appeared as juror at Bury St. Edmunds in disputes between the abbey and the town in 1292–3,30 was almost certainly a grain factor operating beyond the manor; though he also may have held some free land there he was certainly not a customary tenant.31 De Haukedon proved his debt by means of a tally under seal, neither a typical nor yet as we have seen, where traders from beyond the manor were concerned, a wholly unfamiliar mode of proof in the manor court.32 In the same court a Richard Lucas was also impleaded by Stephen de Haukedon for unjust detention of five bushels of wheat worth 10s and two bushels of rye worth 3s while Alex de Raysun was again defendant in a plea that he had unjustly detained 2s 6dfrom William Batayle, money that he should have paid ‘on a certain day’.33 De Haukedon also sought to recover a further quarter of wheat worth 17sand a quarter of beans worth 12s in the same court and from another party, William le Forster.34 Given the very high prices claimed by de Haukedon, which were consistent with the high prices paid for grains in 1316, we might conclude that his decision to call in debts and damages in spring 1316 was an example of opportunism as much as it was of the desperate recovery of a failed credit agreement.35 Importantly, as a proportion of all debt litigated against in the Great Barton courts for the regnal year 9 Edward II (July 1315 to July 1316), de Haukedon was plaintiff in 87 per cent of the total capital pursued, some 84s worth of various grains (out of the total sum of 96s 6d in terms of capital pursued).

The Role of Business-Level Credit Agreements in the Wider Village Economy

It seems highly likely that the withdrawal of credit on this scale will have exerted pressures not just on the principal debtor.36 From time to time we can see what appears to be a response to loss of capital. At Coltishall in July 1325 John Gritlof recognized he owed 45s to Haukyn le mercer (de Gybewic/Ipswich) for a debt originally due for repayment in Christmas 1318. Early in the next year John Gritlof sold a significant amount of land with the purchase price of 23s 4d to be delivered to his creditor, the remainder identified as still to be raised.37 In other instances it seems reasonable to suppose that withdrawal or recovery of credit by the more substantial creditors/merchants/local traders produced a complementary reaction in their debtors, who as middling-type villagers, may have had their own debtors. Thus, for instance, at Hinderclay in April 1312, the pursuit by Nicholas le Reve of one Walter the son of Reginald for the substantial debt of 1.5 quarters of barley (a sizeable amount tied up in a single grain and consistent with trading in barley) may conceivably have generated an unwelcome response for the defendant’s own debtors.38 In October 1312 the same Walter sought recovery of 7s as well as 6d damages from his own debtors, Reginald le Wydewe and Walter le Kyng; we do not know when the initial contract was established in this instance.39 In other instances, we seem to glimpse a run on particular debtors, the recovery of a substantial debt by one creditor encouraging other creditors of the same individual to pursue him or her as well, as is possibly the case at Great Barton in 1316, where the pursuit of Alex Raysun by Stephen de Haukedon may also have encouraged the plea against him by William Batayle.40

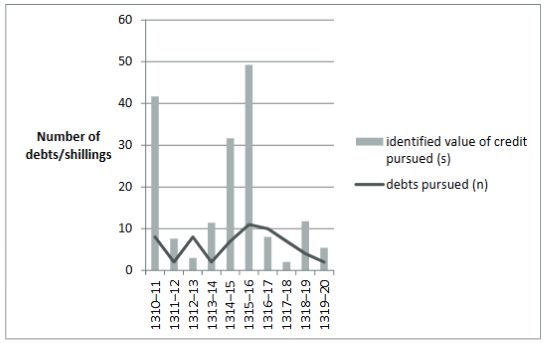

The overall consequence of aggressive withdrawal of credit by individual creditors may have been to limit the local capital supply. If we look more closely at the Hinderclay court roll entries and plot numbers of debt plaints against the recorded amount of credit pursued per annum (where money value has been recorded or, in some few instances, where the grain price can be estimated), we note some significant fluctuation in recovery of debts (Figure 13.3). There is also only a weakly positive (0.368) correlation between the number of debts recovered and the amount of credit recovered. We can observe a large number of transactions in certain years, most notably 1315–16, the first of the Great Famine years followed by what appears to have been a significant diminution in debt litigation and the extent of capital recovered in the years immediately afterwards.

To take this one step further and look at the value of individual recoveries in a particular year (the accounting year Michaelmas 1315 to Michaelmas 1316), is to identify some considerable variety in the size of credit recovered, with the seven instances of debt valued in money terms in 1315–16 ranging from 5d to 16s 4d.41 In addition, an unvalued debt of one quarter of barley and two bushels of malt was also recovered in that year.42 Such examples seem to present a fairly typical range of types of credit being recovered, comprising both fairly short-term and ‘exigency’ credit as well as larger loans or sale-credits, involving unequal parties, originally extended for investment as much as or more than for consumption and for de facto if not necessarily de iure longer terms. It is possible, though it requires further testing in series of manorial courts that will permit an analysis across relevant years, that a run on credit in the first of the Great Famine years, 1315–16, may have reduced the overall availability of credit in subsequent years; it seems possible that, in particular, the withdrawal of very large sums, either in the form of money or in grain, may have had the effect of drawing large amounts of capital out of local credit markets with potentially inhibiting effects.

Individual Credit Agreements and Crisis Events

The larger debt cases, with their uneven and often protracted recoveries, also direct us to some further points relevant to our understanding of credit and of business dealing in the later thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. In the first instance, there is evidently no uniform shock or development that encourages a universal recovery of larger debts. The decision for creditors to seek final recovery of debts owed could, of course, be determined by a considerable range of possible factors, only some of which are suggested by the pleas occurring in manorial courts. A good deal of the material suggests that legal attempts at recovery, perhaps especially of larger debts where such issues as ‘public fame’, reputation and creditworthiness applied, might be initiated long after the true term of the contract had expired. In these instances, what seems to have initiated litigation was not the effluxion of time but some factor external to the contract, such as but certainly not confined to unusually high grain prices or the perceived weakness of a once trustworthy debtor-client.

We might expect that and indeed we have already seen that, c.1300 and especially c.1315–17, high grain prices encouraged recovery of debt. In March 1311 at Hinderclay (Suffolk) and during a year of relatively high prices, Robert son of Adam sought to recover separate debts in money of 11s 8d and 13s 4d, which had respectively been awarded as recoverable in August 1307 or had been loaned almost a decade earlier in September 1302.43 The example from Great Barton (Suffolk), given above, also indicates that high prices in 1316 may have prompted the creditor to recover debts, the payment of which was already overdue. Further to this, if we look at trends over time in debt recovery from manorial court rolls studied to date, we find some patterning and correspondence of years, especially in terms of the very highest price years. That said, as Chris Briggs has noted, we also detect a far from consistent pattern, especially when we look at years associated with high (but not the highest) grain prices. Thus, for instance, the years 1310–11, 1311–12, years associated with higher grain prices, feature only on some manors studied to date (and for which reasonable runs of manorial courts survive) as years of higher than usual debt recovery and not on others. Briggs explains these disparities in terms of the willingness of creditors to extend credit in the previous year.44 In other words, where we see larger numbers of debt plaints we might suppose that a fair amount of credit had recently been made available and where we do not it may be that creditors had earlier decided not to extend credit. Of course, it may also be the case that debtors had not sought credit to any great degree during that period or that they had sought it but had repaid it without recourse to the courts or, to follow the instances offered here, that credit had been extended on terms of different lengths than the estimated norm.

It is certainly the case that some creditors did not seek recovery at all during what appear to have been the periods of highest prices even though there existed contracts in debt upon which they could have sought recovery. Briggs notes at Littleport, in 1317 in the aftermath of the worst years of the Great Famine, recovery of an old debt, ex veteri debito.45 A year later, at Hinderclay in December 1318 Walter Butun sought repayment plus damages for a quarter of barley, four bushels of malt and four bushels of wheat, the repayment date for which had originally been set as eight years previously.46 That such a substantial debt had not been reclaimed during the worst years of the Great Famine is not easily explained, though we might suggest any number of possible scenarios in explanation. Butun’s late attempt at recovery in 1318 might suggest a change in his own fortunes or anxiety regarding the continued creditworthiness of his debtor, Alice le Wodeward. What is clear is that this was, by 1318, one of relatively few debts pursued or indeed recovered. This suggests that the well of available credit may have been running low by this date. We might also want to suggest that if, by the second half of this decade, credit was still extended, it was as or more likely to be extended within particular and privileged groups (what Philip Slavin in an article recently published on the Great Famine refers to, in citing Sheilagh Ogilvie, as ‘particularized trust’).47 We may in fact need to look to the mid 1320s for any evidence of deferred repayments on larger loans and credit sales contracted in, say, the period 1316 to 1320, the relic of higher-order dealing among wealthier or more trustworthy (in financial terms) villagers and, as often must have been the case, their partners external to the manor and village.

Conclusion

If it may prove difficult to associate in absolute and consistent terms some features of credit supply and credit recovery with such a significant shock as the grain price hikes of the early fourteenth century, it is also, inevitably, difficult to make any similar connection with other general developments or shifts. This may be taken to apply, for instance, to historians’ attempts to explain the expansion and withdrawal of credit in relation to adjustments in the money supply. While it is entirely reasonable to identify the money supply, just as the poor harvests and price rises of the second decade of the fourteenth century, as potentially significant factors and highly relevant, contextually, it is almost certainly not possible to claim that local creditors responded with anything approaching universality to, most obviously, the dramatic changes in mint output in the early fourteenth century, any more than it is possible to suggest that there was a universal and entirely consistent response to higher grain prices.

At the local level this also means that the particular shock of a reduced or restricted credit supply (rather than more general shocks associated with factors such as weather or the money supply) could be highly localized and driven by the economic dealing of no more than a few individuals, acting within their own business conventions – but with important consequences for a wider population. It behoves us, in so far as we can, to explore these particular factors and test their significance to the limits of our sources. The behaviour of plaintiff-creditors or defendant-debtors in one context, the local manorial court, may, undoubtedly, have also been occasioned by what are to us less visible judgments against them in other, manorial or non-manorial courts, again a reflection of dealing beyond the manor of the kinds set out in some of the instances already offered here. Seigneurial injunction against villein tenants suing and being sued in other courts has typically been explained in terms of the threat such action posed for the lord’s property;48 while that was almost certainly uppermost in the minds of lords, such action – which clearly did take place with or without lordly sanction – and the threat to social cohesion and everyday dealing in village society of local capital lost to other jurisdictions and to those dealing in them cannot have been without significance.

Further to this, but to take a slightly different tack, we have seen that creditors and debtors involved in some of the largest credit agreements sometimes allowed such agreements to run on for a number of years. This could work for and against the benefit of the local economy. While creditors may for a number of reasons (charity and religious conviction, social capital and public reputation, indolence, the significance of the debt relative to their overall business dealing/credit portfolio, and/or their overall confidence in the systems that supported eventual recovery) have chosen to permit unpaid debts to languish, it is possible that their failure to recover served to inhibit local markets. Major creditors may, on account of sluggish repayment, have been simply less efficient in their particular markets and dealings while local debtors, middling villagers, with the threat of a large debt repayment hanging over them for years at a time, may also have been inhibited in their own dealings at the local level. Of course, this is not for one moment to suggest that the general climatic or institutional shocks and crises were not significant, as clearly they were, but it may encourage us to the view that crises in credit could be particular and occasioned by failed credit agreements operating at the level of the individual, and most often the individual trader or merchant.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 13 (253-270) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons license.