The personnel focalization of a number of cults was somewhat blurred.

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Roman gods were conceptualized not only by spatial and temporal foci, but also by the people who administered these foci. To speak of ‘personnel foci’ here and not simply of priests has the advantage of moving away from such notions as ‘status’ or ‘profession’ towards ‘concepts’. This is necessary, because in conceptual terms there was no fundamental difference between, say, a flamen or any random citizen when offering a sacrifice or reciting a prayer. By repeating cultic actions within specific spatial and temporal settings, both groups ‘recreated’ the same (or at least a very similar) divine concept, though of course in completely different ways.192

As far as the term ‘priest’ is concerned, the discussion among scholars about whether the term can be adequately applied to Roman conditions has, in my view, been both futile and damaging. Futile, because no complex concept, expressed in any language, can fully render the notion of any complex concept of another language (for our purpose, one may compare the lack of a Greek equivalent to Latin divus). Damaging, because it suggests that this can be done in cases other than the concept of ‘priest’. The term ‘priest’ remains a useful makeshift expression for a personnel focus of a cult that, with the explicit and normally canonized approval of a number of people, acts in specific religious matters as a representative of these people.

Roman priesthoods may be conveniently divided into official and unofficial priesthoods. Official priests served to establish and maintain good relations between the gods and the state. They acted on behalf of the state and were controlled by the senate and later the emperor. In addition, official priesthoods were unpaid, with the position carry-ing considerable prestige. On the other hand, unofficial priests dealt with relations between the individual and the divine. Their ultimate goal was to satisfy personal needs, and they were paid in kind or in money. Unofficial priests could perform functions from self-appointed magicians and prophets, to respectable specialists in recognized though unofficial cults or observational techniques. The former category was the domain of the Greek “pseudo-priest and fortune-teller” (sacrificulus et vates)193 who introduced the ill-omened cult of Bacchus to Rome which ultimately led to the Bacchanalian affair in 186 B.C.; or Licinius, mentioned in Cicero’s Miloniana, who made a living from performing purificatory rites for families in grief;194 among the latter category, we may count the Etruscan soothsayers (haruspices), who regularly served both individual magistrates and the state as a whole for the interpretation of portents, although this was of an unofficial nature.195

The two most important sacerdotal colleges in the Republic were the pontifical college (collegium pontificale), headed by the pontifex maximus, and the augural college (collegium augurum). Both colleges, whatever their origin, kept their autonomy throughout Roman history. During the Republic, their independence was marked by the existence of separate archives,196 by the fact that the augurship, once bestowed upon a candidate, could not be taken away from him, even if the incumbent went into exile or was otherwise convicted,197 as well as by the fact that the augur was not subject to the directives of the pontifex maximus.198 In other words, the functions of pontifical college and augurate are to be kept strictly apart.199

In the Republic, the personnel focalization of official cults is strongest in the case of the flamines, i.e. the official priests, each of whom was in charge of the official cult of a specific god in the city. Later flamines took charge also of the cult of the emperor, thus implying that the flamen was considered to be the individual priest of a deity par excellence (in marked contrast to the priestly colleges). It suffices here to refer to their most important representative in the Republic, the flamen of Iuppiter. Like this god among official gods, his priest ranked highest among the flamines, second only to the rex sacrorum in the oldest known priestly hierarchy.200 His wife, the flaminica, performed ritual functions and therefore complemented her husband’s role.201 The flaminica was perhaps priestess of Iuno (who had no flamen).202 This explains why the flamen Dialis was not allowed to divorce, why the flaminica was permitted to marry only once (univira), and why her husband had to lay down his priesthood on her death: for together, flamen Dialis and flaminica represented the divine duality Iuppiter and Iuno. Apart from that, the various, partly abstruse restrictions imposed upon the flamen Dialis enhanced the focal character of his priesthood, in that they deprived him of the opportunity to lead an ordinary life and to participate in that of others. In other words, his enforced social isolation led to an increase in and emphasis on this personnel focus of the concept of Iuppiter.

Naturally, unofficial cults display the same personnel focalization. Let us take the example of the cult of Bacchus in ca. 200 B.C. Initially, this cult was administered by women alone. Matrons were chosen in turn as priestesses (sacerdotes).203 This status was not affected by the Tiriolo decree, which was issued by the senate against the cult in 186 B.C., for in it both the existence of female followers (Bacchae) and that of female priests (sacerdotes) were implicitly granted.204 After reforms in ca. 210 B.C., male initiates had started to participate in the cult205 and the office of ‘master’ (magister) had presumably been created. By the time of the Tiriolo decree, men were on an equal footing with women, either as priests (sacerdotes) or ‘masters’ (magistri).206 Livy even indicates the existence of a priestly hierarchy (maximi sacerdotes), but it is not clear whether this hierarchy was based on personal prestige or distinct sacerdotal competences.207 It is reasonable to assume that priests performed initiations and sacrifices in the presence of other cult members.208 The ‘masters’ also attended to sacrifices.209 However, their main concern was presumably the administration of common funds, apparently contributed by adherents of the cult.210 The whole structure, especially the existence of magistri and the participation of both slaves and freemen in the cult, is strongly reminiscent of corporations (collegia) that often rallied around a specific god.211

Any increase in ritual duties may lead to a specialization of duties. This tendency towards specialization is particularly tangible in the case of the personnel foci of the cults of oriental gods in Rome, such as that of Iuppiter Dolichenus or Isis. Let us take the case of Isis.212 Initially, we hear only of priests in general. A first-century B.C. inscription from the Capitoline region provides proof of the existence of a male or possibly female priest (sacerdos) of Isis Capitolina, possibly in connection with other adherents or even functionaries of the cult.213 A priest of Isis Capitolina also appears in a later inscription, dating to the end of the first century A.D. at the very latest.214 Some literary sources imply the presence of male Isiac priests, possibly on the Capitol, in 43 B.C., while others do so for the year 69 A.D.215 Ovid knows of the appearance of the priests (but he would not necessarily have learnt about them from Rome).216 The only witness to a possible specialization among the personnel foci of the cult of Isis at this early stage is Apuleius (writing in the second century A.D.). He claims that already under Sulla a congregration of Isiacs, the pastophori, was established in the capital.217 However, relevant inscriptional evidence is lacking.218

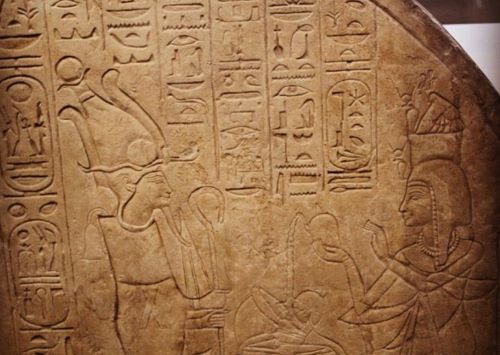

It is in the second century A.D. and later, with the rising number of adherents to Isis, and under more favorable political conditions, that manifold specialized priesthoods of the goddess emerge, which were as a rule modelled on Egyptian conditions. Most important, perhaps, is the existence of a ‘high-priest’ (prophetes) in Rome in the first half of the second century A.D. He appears epigraphically and is also depicted, for instance, on a relief along with the keeper of the holy books (hiero-grammateus) and an unspecified priestess of Isis (sacerdos). The relief was found in the capital and dates from the Hadrianic period.219 One may add the ‘astromoner’ (horoscopus), who, as with the keeper of the holy books, is known from Rome only by representations in visual art,220 as well as the ‘singers’ (paianistes),221 and possibly those ‘who dressed the divine statues’ (stolistai), though there is as yet no direct evidence for the existence of the latter in Italy.222 Next, there are the pausarii, performing pausae, perhaps some ritual ‘stops’ during Isiac processions.223 This increase of priesthoods, i.e. of personnel foci of the cult of Isis, allowed a much larger number of people to actively participate in it. It is thus an indicator both of the increase in popularity and at the same time of the gradual Egyptianization of the cult.

On the other hand, specialization of personnel foci could lead to a secondary connection with the cults of specific gods. Therefore, the augurs, originally clearly without a specific link to any god, became ‘priests’ of Iuppiter because of one of the main areas of their expertise, viz. defining space in the heavens.224 One may also refer to the III/VII/Xviri epulones and the II/X/XVviri sacris faciundis. Both priesthoods grew out of special duties of the pontifical college, the former, to organise the two sumptuous feasts held on the occasion of the ludi plebei and the ludi Romani, the latter, to consult the Sibylline Books. Since the Games were connected to Iuppiter and the Sibylline books to Apollo, they were later interpreted as personnel foci of the cult of Iuppiter and Apollo respectively. But the cult of Apollo was a nonentity until the Augustan age and would by no means have justified the existence of an independent priesthood until then. This clearly proves that the II/X/XVviri did not begin as personnel foci of the Apollonian cult.

The divinity of the emperor was, as I have repeatedly suggested, modelled on that of the traditional gods. This suggestion is further supported by the aspect of personnel focalization. Augustus, for example, received a flamen after his death in 14 A.D.,225 deliberately avoiding the dire Caesarian precedent of a flamen during his lifetime.226 Augustus’ flamen was the first in a long series of flamines of divinized emperors in Rome until the third century A.D. At least until the end of the Julio-Claudian era, the imperial flaminate in Rome remained the domain of the imperial family.227 However, not all divi actually received a separate flamen: at least one flamen officiating a joint worship of Divus Iulius and Divus Augustus is on record.228

Interestingly, as in the case of other important gods, the cult of the deified Augustus focused on more than one priest. Thus, Livia became Augustus’ priestess in 14 A.D. The circumstances under which this happened clearly indicate competences of the new priestess far beyond a mere private cult. Her priesthood was presumably modelled on the vestal virgins, though its exact status remains obscure.229 Better known is the association (sodalitas) of Augustales, established by Tiberius in 14 A.D. It consisted of twenty-one Roman aristocrats chosen by lot, to whom members of the imperial family were added. The association was not bound to the individual emperor, but to his gens. In the same vein, comparable associations were linked to other imperial dynasties (sodales Flaviales, Hadrianales, Antoniani).230 Tiberius had made it crystal-clear that the sodales Augustales were not on an equal footing with other official priesthoods such as the pontiffs. Rather, the former were exclusively priests of the imperial family (proprium eius domus sacerdotium).231 But the very fact that such an explicit ruling was necessary, apart from the reappearance of the sodalitas in connection with the four major priesthoods in 31 A.D., sufficiently demonstrates their focal character in the imperial cult.232

It is more likely than not that the flamines, as we know them in the historical period, reflect the individual personnel foci of an early, pre-historical stage of the Roman pantheon. This means that originally they focused on the cult of a single god, as is indicated by their name (e.g. the flamen Dialis as the priest of Iuppiter). Conversely, we may postulate that originally, official rites to gods that possessed a flamen were performed predominantly or exclusively by this priest.

Entering the historical period, this personnel focalization of a number of cults was somewhat blurred. Members of the pontifical college could stand in for each other. For instance, the pontiffs could replace the flamen Dialis apparently in all or most of his functions (and presumably had to do so during the long vacancy of this office from 87 to 11 B.C.).233 Furthermore, Tellus received sacrifices from both the flamen Cerialis and the pontiffs,234 and the flamen Dialis was perhaps involved in the Lupercalia, i.e. the cult of Faunus.235 Similarly, the flamen Quirinalis performed rites for Robigus236 and Consus (along with the vestals).237 True, most of the deities concerned did not have a specific priest, and therefore priests of other deities had to help out. However, there is reliable information that the flamen Portunalis was involved in the cult of Quirinus (who demonstrably had his own flamen),238 that the flaminica Dialis was somehow connected to the cult of Mars (who likewise had a flamen and presumably also a flaminica Martialis)239 during the ritual of ‘moving the ancilia’.240

Some scholars may want to argue that this functional diffusion actually indicates that the flamines did not form personnel foci of specific gods before the introduction of the imperial flamines after Caesar’s death. In their view, the major priests, including the flamines, belong to no particular cult, and have no particular responsibility for the rituals or spaces of any particular cult rather than for those of all the cults. According to this line of reasoning, the colleges are divided by functions (auspicia, sacra, war and peace, prophecy etc.), not deities. They may accuse me of arbitrarily constructing an early Rome or a pre-Roman Rome in which all was rational and consistent, implying a steady process of centuries of decline and confusion, as the élite became either negligent or sceptical or both.

I am ready to concede that the initial degree of focalization of the flamines cannot be determined accurately. Still, I hold that this degree must have been considerable, for a number of reasons. To begin with terminology, all flamines are determined by an adjective indicating the divine concept with which they were connected (flamen Dialis, Martialis etc.). They are the only priestly college endowed with such markers of focalization. Second, some of the flamines thus determined were con-nected to very central deities of the later pantheon (e.g. Iuppiter, Mars). They ought not therefore to be considered accidental ingredients of an existing pantheon, but constituent elements. Third, some minor flamines, such as the flamen Falacer or the flamen Furrinalis (only Varro ling. 5.84; 7.45 [Ennius]) were connected to gods that had virtually disappeared from the Roman pantheon already in the Republic. The preservation of their names can be explained only on the assumption that these names concealed meanings relevant to the differentiation among the flamines themselves. Fourth, had the flamines been in charge of all or a large number of cults, the subdivisions of this group in flamines maiores (to which the non-patricians never gained access in the Republic) and minores, and the setting aside of the flamen Dialis by taboo regulations, would hardly make sense. It is much more plausible to assume that these subdivisions are based on a latent divine hierarchy, at the top of which stood the triad of Iuppiter, Mars and Quirinus, with Iuppiter heading the ensemble. One should also bear in mind that as their name (‘bridge-builders’) suggests the later sacrificial priests par excellence, the pontiffs, did not start as religious personnel at all. It is fair to conclude that the flamines came into being as the sacrificial priests of specific gods, or groups of gods, which were conceptualized as a unity for some reason. As for inconsistencies, one should bear in mind that in this book we speak of personnel foci, whereby focalization implies emphasis, not exclusiveness.

As to the subsequent ‘decline’ and ‘confusion’, these notions are misleading in so far as they presuppose rigidity and inalterability of concepts. By contrast, this book takes the view that concepts are constantly derived and developed from each other. This fact offers a precise explanation of some of the inconsistencies. For instance, the fact that Tellus received sacriFIces from the Flamen Cerialis may be explained by the similar functional focus of Ceres and Tellus as chthonic fertility deities. When we hear that the flamen Quirinalis officiated rites for Robigus, this statement becomes less surprising if we consider that the Games held at the Robigalia were dedicated to Mars and Robigus241 and bear in mind the observation that the functions of Mars and Quirinus as martial gods were almost identical. The same common denominator of the concept of ‘war’ may explain the substitution of the flaminica of Mars for the flaminica of Iuppiter during the martial ritual of ‘moving the ancilia’. Of course, due to the lack of evidence it is rarely possible to trace back the conceptual string with certainty. But the conceptual approach allows for a state of flux.

A particularly enlightening case showing such interaction of a personnel focus of the cult of a god with that of other gods is the flamen Quirinalis. The priesthood of the flamen Quirinalis was allegedly created by Numa and belonged to the privileged group of three flamines maiores (next to the flamines of Iuppiter and Mars), i.e. patrician flamines who had to be married by confarreatio, as opposed to the twelve plebeian flamines minores.242 In fact, the flamen Quirinalis was fourth in place in the oldest known priestly hierarchy and ranked ahead of the pontifex maximus.243

The office of the flamen Quirinalis must then have been prestigious in the early period of Roman religion, when the god was in the heyday of his powers.244 At some unknown, but certainly early stage, his fortune changed. The reason was no doubt functional competition with Mars.245 The latter occupied a paramount place as the god of war par excellence (along with other competences) in Rome as well as other parts of central Italy. The early symbiosis of both Quirinus and Mars is manifested by the existence of the two colleges of Salii, one belonging to Quirinus and located on the Quirinal (⇒Salii Collini/Agonenses), the other belonging to Mars and stationed on the Palatine (⇒Salii Palatini, later located in the temple of Mars Ultor).246 Although the institution of Salii itself is not peculiar to Rome,247 the parallel existence of two such colleges, with apparently identical cultic functions but completely different cult locations and traditions, is. It finds its most natural explanation in the assumption that, at some stage, the two priestly colleges operated independently. Possibly one was the college of the people of the Quirinal (and Viminal), the other was the college of the other hills. Such a bipartite structure may well reflect the organization of the old city, which appears to have been divided into Quirinal and Viminal on the one hand and the remaining hills on the other (Palatine etc.).248

Being in competition with Mars, the cult of Quirinus gradually declined.249 This development affected the institution of the flamen Quirinalis. The priest lost power and prestige. We cannot know for certain whether the (unofficial) identification of Quirinus with Romulus was, in fact, fabricated by the priests of Quirinus as a response to this loss. However, once it began to circulate at the beginning of the second century B.C. or slightly later, the priests of Quirinus had more than one reason to promote and advertise it.250 For Quirinus thus received a new, well-defined sphere of competences as the founder of Rome and the son rather than competitor of Mars, the god of war. Such an identification with Romulus was all the more suggestive, in that Romulus did not possess a specific priest of his own.

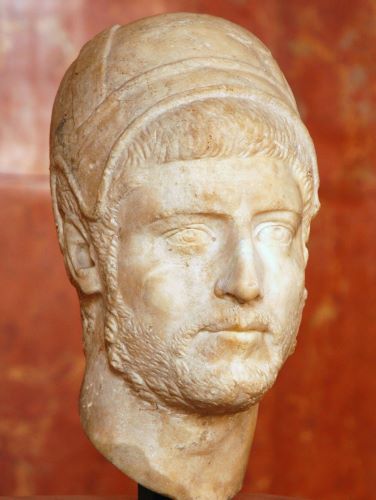

We may be able to identify the creator or at least a fervent promotor of the identification of Quirinus with Romulus. Q. Fabius Pictor, son of the historian, was flamen Quirinalis from 190 to 167 B.C. and the most famous incumbent of this office. He appears repeatedly in Livy in his capacity as flamen, most notably on the occasion of his dispute with the pontifex maximus P. Licinius: Flavius had been appointed to the praetorship in Sardinia but had to resign from the post due to religious constraints after intervention by Licinius (Flavius became praetor peregrinus instead). Still, the impression Flavius made was lasting, so lasting that his grandson, the moneyer N. Fabius Pictor, issued a denarius in 126 B.C., depicting his grandfather as flamen.251 Both the chronological framework and the apparent political ambitions of Q. Fabius Pictor would make him a suitable exponent for the identification of Quirinus with Romulus.

Whatever the case may be, the identification of Quirinus with Romulus remained unofficial, at least until the Augustan age. This is implied by the fact that until then, at least, sacrifices to Romulus continued to be performed by the pontiffs and not by the flamen Quirinalis. Rituals at the ‘hut’ of Romulus were still conducted by the pontiffs in 38 B.C., although the flaminate of Quirinus was occupied until at least 46 B.C. (though a later vacancy cannot be excluded).252 In the same vein, Acca Larentia, foster-mother of Romulus and Remus according to widespread beliefs circulating from the first half of the first century B.C.,253 received regular sacrifices by the pontiffs in 43 B.C.254 Later, such sacrifices were performed—clearly as a consequence of the identification of Quirinus with Romulus—by the flamen Quirinalis.255

Quirinus is not the only instance in which priests deliberately pro-moted the assimilation of their own vanishing god with another. A case in point is Iuppiter Dolichenus. Two reliefs found in the god’s Aventine sanctuary, and dating from the end of the second and middle of the third century A.D. respectively, show Isis and Sarapis as participants in the divine kingdom of Iuppiter Dolichenus as well as his spouse, Iuno Dolichena. The earlier of the two reliefs is inscribed: “To Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Dolichenus Serapis and Isis Iuno” (I(ovi) o(ptimo) m(aximo) Dolicheno Serapi et [Isidi I]unoni). Furthermore, antefixes and statuettes with Egyptian motifs were also found in the sanctuary. It is therefore a qualified guess that Isis and Sarapis were worshipped in the place, either in the form of Iuppiter Dolichenus and Iuno Dolichena or possibly in their own right (a number of sculptural representations of other gods such as the Dioscuri, Mithras, Minerva, Silvanus, Diana, Hercules and others were also found). In any case, Vidman is clearly right in suggesting that this assimilation (not necessarily identification) with the Egyptian deities (as well as other gods?) was promoted by the priests of Iuppiter Dolichenus in an attempt to render their cult more attractive by embracing more successful divine partners. Nevertheless, the Aventine cult of Iuppiter Dolichenus faded into obscurity not much later than the end of the third century A.D.256

Under the Empire, the focal force of the personnel foci of the traditional Republican cults disappeared. One indicator of this disappearance is the well-known scarcity of references to the traditional flamines in imperial sources. Even if we grant that these flamines, especially the flamines minores, may have been indifferent towards mentioning their priesthood in the inscriptions, or may rather have been interested in mentioning it in a different guise (because the flaminates themselves had no longer ‘communicable prestigious potential’),257 this would only serve to prove that they had ceased to be significant personnel foci of the deity. This may have happened because the cult itself was in decline, or because the traditional focalization of the cult through the flamines had been abandoned or shifted elsewhere. Those flamines who were attested, may well owe their attestation to a certain popularity of the feriae of the god they represented.258 But statistics are too limited for further conclusions, although it is a fair guess that some flaminates existed until at least the beginning of the second century A.D.259

It was predominantly the advent of the imperial cult, among other factors, that led to the abandonment of the focal system of the Republican cults and in the long run, to its complete dissolution. For by widening the various foci towards the ruler cult, they lost their very focal character and therefore ceased to serve in a capacity that was characteristic of traditional divine concepts. Interestingly, the most important personnel focus of the imperial cult, the imperial flamen, was initially calqued on the personnel focus of the Republican cult par excellence, the flamen Dialis: for both the attire and the privileges of the imperial flamen imitate the Jovian priest.260 Clearly, this happened in order to lend glamour to the personnel focus of the imperial cult. The intentional fusion of the personnel foci of the central Republican and the imperial cult can be demonstrated by another example. Domitian used to attend the quinquennial Games of the Capitoline Iuppiter, wearing a golden crown depicting the Capitoline triad, a clear conceptual assimilation to the functions of the flamen Dialis. By contrast, the same crown, though with an image of the emperor added, was worn by the flamen Dialis on the same occasion, stressing the link of the latter with the imperial cult. Similarly, members of the priestly college of the Flavians (collegium Flavialium) were present wearing crowns identical to that of the flamen Dialis.261 Therefore, in conceptual terms the flamen Dialis was both highest priest of Iuppiter and, it could be argued, guarantor of the cult of the Flavians.

The merger of Republican personnel foci with the imperial cult can also be demonstrated by the development of the arval brethren: this old priesthood of Dea Dia may, in the Republic, at times also have performed the cult of Mars and that of the Lares and Semones, as is apparent from the ‘hymn of the arvals’.262 When the cult was restored under Augustus, connections with other Republican cults were largely cut, and this is why we never find the imperial arvals involved in the traditional Republican ceremonies of other gods.263 By contrast, the arvals, to a large extent, became personnel foci of the imperial cult. For example, there are numerous records of their making vows annually for the welfare of the emperor and his family on January 3 and frequently on other dates.264 On these occasions, especially in the Tiberian period, Dea Dia was normally invoked in the fourth position (following the Capitoline triad). However, any reference to the name of the goddess disappears completely in vows taken after 38 A.D.265 Moreover, from the second half of the first century A.D., the imperial cult had its own building, a Caesareum, in the grove of Dea Dia.266 The frequency of meetings of the brotherhood in order to worship Dea Dia, as compared to those gatherings devoted predominantly to the imperial cult, were heavily biased towards the latter until the Flavians somehow redressed the balance by cutting back on imperial observances.267

In short, the imperial cult had appropriated the personnel foci of the cult of Iuppiter and Dea Dia during the imperial period and essentially invalidated the notion of traditional cultic focalization. This defocalization of the personnel foci of the cult of Dea Dia under the Empire is likewise manifested by the fact that, in addition to the annual sacrifice at the temple of Dea Dia, the arvals used to perform various rituals in the private residence of their magister or at other temples of the city, especially in the temple of Iuppiter on the Capitoline.268 One may argue that major Republican priesthoods did not have a special location of their own either.269 But there was still a difference between privately gathering for administrative purposes (as was presumably done by the arvals as well as other priesthoods in the Republic) and actually performing public cult (by implication bound to public spatial foci). I would argue that by integrating the ruler into their regular observances, the imperial arvals lost their strict focus on the cult of Dea Dia. It is at least a plausible guess that the same happened to the personnel foci of the remaining official cults also.

A long list of potential personnel foci of the Jewish god in the Graeco-Roman world can be drawn up, but the validity of such a list for the conditions of urban Rome as well as the actual functions of this personnel is still heavily disputed. At many places, including Rome, the position of the archisynagogue may have been the primary personnel focus, assisted perhaps by a council (gerousia). However, neither such a council nor a superintending council of synagogue councils is unequivocally attested for Rome, and its existence cannot unreservedly be postulated on the basis of the situation in Alexandria.270

The earliest sources for personnel foci of the Christian god are the first epistle of Clement, presumably written around 96 A.D. in Rome, and the first epistle of Peter, which is likely to have been written in Rome and certainly belongs to the late first century A.D.271 Though it may not be exactly clear to what extent the facts described in both letters reflect Roman conditions, the two authors appear to visualize a similar and widespread structure of Christian communities. Given the importance of the Christian community in Rome and the likely provenance of both epistles from the capital in particular, it is a fair guess that the evidence afforded by both documents applies also, and predominantly, to Rome. If this is the case, two groups of Christian officials can be identified in the capital at the end of the first century A.D., namely a board of presbyters (presbyteroi, also called episkopoi), and the deacons (diakonoi). The presbyters drew their legitimation from the succession of Jesus via the apostles.272 It was the council of presbyters that collectively managed the affairs of the Christian community in Rome until the middle of the second century A.D.273 However, already at the beginning of the second century A.D. Ignatius of Antioch had laid the theoretical foundation for the monoepiscopate, by assigning a single head, a bishop (episkopos), to each community, supported by an advisory council of presbyters, while the deacons were put in charge of charity work.274 This structure is first attested in Rome during the middle of the second century A.D., beginning perhaps with the popes (= monoepiskopoi) Anicetus (154–166?), Soter (166?–174) and Eleutherius (174–189). It is especially with Victor (ca. 189–199) that the exceptional powers of the popes were stabilized.275

As in the case with other newcomers such as the cult of Isis, we observe an increasing specialization of personnel in the course of the third century. Thus, one of the most successful organizers of the new Church, Pope Fabian (in office 236–250 A.D.), assigned two Augustan regions of Rome to one deacon (out of seven) assisted by a subdeacon in the middle of the century. Apart from the latter, there were 46 presbyters, 42 acolytes, 56 lectors, exorcists and door-keepers in the capital shortly after Fabian’s death.276 If we were to summarize the third-century development of personnel foci of the Christian god, we should mention a growing concentration of power in the hands of the bishop of Rome, and an equally increasing local and hierarchical differentiation of the remaining personnel foci. There does not seem to be any essential difference in terms of power constellation between the personnel foci of the Christian god and those of other oriental gods, most notably Isis.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 1.3 (51-66) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.