There was a wide eighteenth-century market for images of various kinds.

By Sheila O’Connell

Former Curator of British Prints

The British Museum

What printed images were to be seen on British streets in the eighteenth century?1 Before discussing the market for — and publication of — cheap pictorial prints, it is worth paying some attention to the range of small printed images that would have been familiar to people at all levels of society in towns and (to a lesser extent) in rural areas. In Britain, where literacy was relatively high compared with other European countries, such images usually accompanied text of some sort. We know that illustrated ballads, discussed in other essays in this volume, were sold on the streets from the early days of printing.2 Many other printed images appeared as part of advertising material of one kind or another.

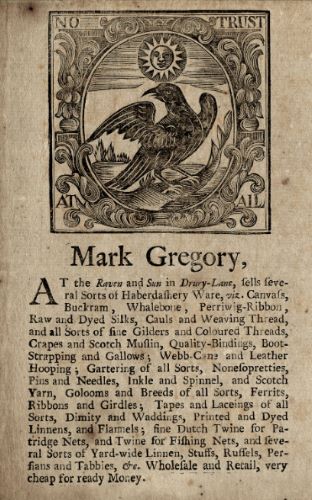

Handbills, known as trade cards, were produced by traders of many kinds to be given out to potential customers in the streets. Poorer people would not have been the target for such prints, but they would certainly have come across them and perhaps even have been paid small sums to distribute them, just as their descendants today press advertisements on passers-by in busy shopping streets. Most trade cards advertised expensive goods and services, but the occasional example might have been of practical use to someone needing to earn a living. For example, Mark Gregory (1698–1736), at the sign of the Raven and Sun in Drury Lane — never a prosperous street — advertised that he sold the sorts of materials that a poor seamstress would use: ‘several Sorts of Haberdashery Ware […] Wholesale and Retail, very cheap for ready Money’ (Fig. 3.1).

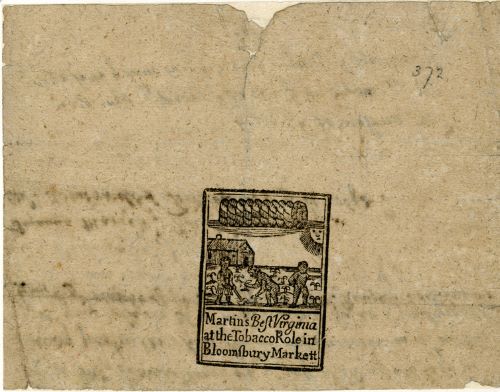

Tobacconists’ advertisements appeared on the twists of paper in which tobacco was sold to smokers. Like trade cards, these showed shop signs (an essential indication of a trading address before street numbering was introduced in the 1760s) and were often illustrated with scenes of black or Native American workers in the tobacco fields, or else smokers relaxing with pipes (Fig. 3.2). The smokers shown were well-dressed men lounging elegantly, but tobacco was used by the poor as well as the rich. Many views of humble working people, or even beggars, show both men and women with pipes in their mouths.3 Tobacco wrappers would have been commonplace, so much so that in the 1790s members of the Association for Preserving Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers complained of radical propaganda printed on such wrappers.4

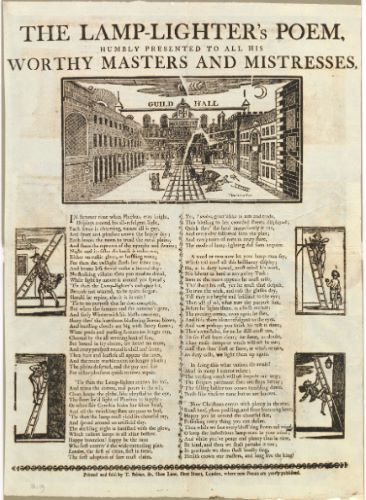

Bellmen (night-watchmen) and lamplighters, surely to be identified among the poorer eighteenth-century workers, distributed prints on their own behalf when appealing to wealthy local residents for Christmas and New Year gifts.5 These sheets were fairly large, measuring about 50 × 35 cm, usually with a relevant woodcut of a man with lantern, dog, and bell, or of a lamplighter climbing a ladder to fill the street lamps with oil, but other illustrations might be from old woodblocks used more or less as decoration. The same sheets would be sold to bellmen or lamplighters by publishers, with little variation year after year. Thomas Sabine, for example, used the same woodblock showing a lamplighter falling from his ladder on at least two different sheets (Fig. 3.3).6

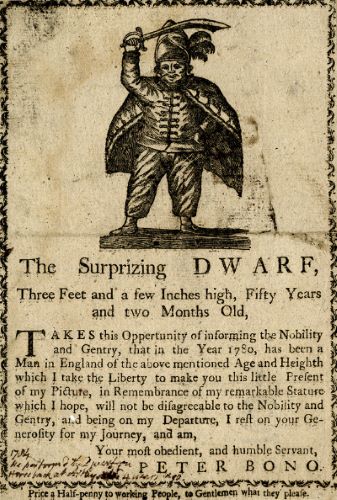

Tickets for exhibitions of extraordinary people or exotic animals usually cost 1s., a high price at a time when a poor family was expected to be able to live on 5s. per week, but perhaps someone a little further up the social scale might be tempted by a ticket showing an unknown creature brought from across the world, an extraordinarily tall or fat person, or a curiosity such as a ‘Learned Goose’ which could read letters printed on cards.7 One surviving handbill, which at first glance seems to be a ticket for such an exhibition, must actually have been sold in the street by the man portrayed, Peter Bono, ‘The Surprizing Dwarf’. Bono’s handbill shows a woodcut of a small man dressed in loose trousers and wielding a curved sword, and the text states that he has been in England since 1780 and is now offering ‘this little Present of my Picture […] Price a Half-penny to working People, to Gentlemen what they please’ (Fig. 3.4).

Other ‘shows’ where cheap printed images were available were public executions, at which vendors sold the ‘last dying words’ of condemned felons. Early examples were pious texts with only simple emblematic illustrations, published by the prison chaplain, but by the end of the eighteenth century commercial publishers issued sheets illustrated with woodcuts showing an execution with its crowd of onlookers. The composition often repeated the view of William Hogarth’s Idle ’Prentice approaching the ‘triple tree’ at Tyburn (1747), with the last words of Thomas Idle being sold by a young mother in the foreground of the scene. In Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode (1745) the unfortunate bride dies with a broadside of her lover’s dying words at her feet.

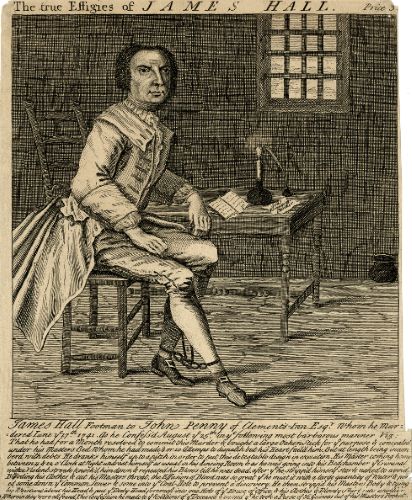

As always, there was a wide eighteenth-century market for images of crime and criminals. On 18 October 1750 Horace Walpole wrote to his friend Horace Mann in Florence: ‘You can’t conceive the ridiculous rage there is of going to Newgate; and the prints that are published of the malefactors, and the memoirs of their lives and deaths set forth.’8 Walpole himself had bought Hogarth’s small painting of the murderess Sarah Malcolm.9 Notorious cases like Malcolm’s — she had murdered and robbed an old lady and her two servants in 1733 — were exploited by publishers to sell prints. Most would have been run-of-the-mill 6d. prints, but there are cheaper examples, like a 3d. print of James Hall — a servant who killed his master in 1741 — shown seated in his cell in an improbably elegant pose (Fig. 3.5). A cheap print like this might well have been sold opportunistically at Hall’s execution.10 This image and other cheap prints of eighteenth-century convicts, as well as other ‘curious persons’, have survived thanks to the enthusiasm of collectors of the period for portraits of all sorts.

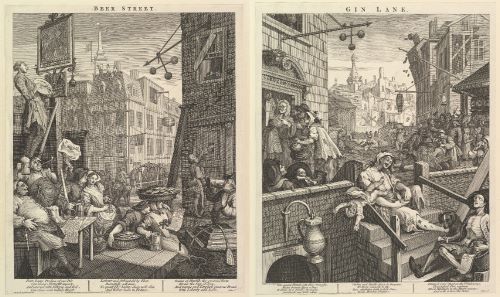

Hogarth was a highly successful artist catering to the top of the market, but his subjects often reflect street life. Another of his paintings, The March of the Guards to Finchley (1750), and the print made after it, show that cheap pictorial prints with little or no text were sold on the streets of Britain by the middle of the eighteenth century. Similar prints could be purchased in the Roman Catholic countries of Europe at a much earlier date. For example, an Italian street vendor of large religious images is depicted in the series L’Arti per via (‘Trades of the Street’, 1660) by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli after designs by Annibale Carracci.11

Large prints of popular subjects were certainly published in Britain at that time, but they do not seem to have been sold at prices that poorer people could afford before the eighteenth century. In Britain, moreover, the ‘papist’ images that found purchasers in the Italian streets were frowned upon, and patriotic and military subjects were more likely to be seen. There are examples of cheap prints relating to Queen Anne in the British Museum, such as a crudely etched and badly printed large print (measuring about 40 × 52 cm) showing the procession to her coronation in 1702, published by John Overton (see below), and a broadside of 1714 (measuring about 33 × 20 cm) published by Robert Newcomb of Fleet Street, with a crude woodcut illustrating text celebrating her reign and lamenting her death.12

Some three decades later, as soldiers march off to defend London against the Jacobite threat, Hogarth’s painting has a pregnant street-crier selling a sheet with the national anthem and a print, which appears to measure about 30 × 15 cm, showing a portrait of the commander-in-chief, Prince William, Duke of Cumberland. Another military leader, General William Howe, then leading British forces in the American War, appears in a large print being sold in the street by an elderly ‘pinner-up’ in a painting by Henry Walton, A Girl Buying a Ballad (1778).13 Although neither painting can be taken as definitive evidence for specific cheap prints on sale in the street, it is clear that large pictorial prints were widely available at low prices in the second half of the century.

Such prints have rarely survived, however. While trade cards, ballads, and cheap portraits of the period have all been preserved in large enough numbers to allow for an understanding of their production and purpose, there are no major collections of cheap pictorial prints.14 Nevertheless, huge numbers were made and sold. Evidence of their popularity is to be found in the Memoir of Thomas Bewick, writing in the 1820s about his Northumbrian childhood sixty years earlier, who recalled:

[…] the large blocks, with the prints from them, so common to be seen, when I was a boy, in every Cottage & farm house throughout the whole country — these blocks, I suppose must, from their size, have been cut the plank way on beech or some other kind of close grained wood, & must also, from the immense number of impressions from them, so cheaply & extensively spread, over the whole country, must have given employment to a great number of Artists in this inferiour department of Wood cutting, and must also have formed to them an important article of traffic — these prints, which were sold at a very low price, were commonly illustrative of some memorable exploits — or perhaps the portraits of emminent Men who had distinguished themselves in the service of their country, or in their patriotic exertions to serve mankind — besides, these, there were a great variety of other designs, often with songs added to them, of a moral, a patriotic or a rural tendency which served to enliven the circle in which they were admired — To enumerate the great variety of these pictures would be a task — A constant one in every house, was ‘king Charles’s twelve good rules’ — representations of remarkable victories at Sea, and battles on land, often accompanied with portraits of those who commanded & others who had born a conspicuous part in those contests with the enemy. — The House in Ovingham, where our dinner poke was taken care of, when at school, was hung round with views or representations of the battles of Zondorf & several others — the portraits of Tom Brown the valiant Granadier — Admiral Haddock Admiral Benbow and other portraits of Admirals — A figure or representation of the Victory man-of-War of 100 Guns, commanded by Admiral Sir John Balchen, & fully manned with 1100 picked Seamen & volunteers, all of whom & this uncommonly fine Ship were lost — sunk to the bottom of the Sea — this was accompanied with a poetical lament of the catastrophe […] Some of the Portraits I recollect, were now & then to be met with, which were very well done in this way, on Wood — in [Bewick’s schoolmaster] Mr Gregson’s kitchen one of this character hung against the wall many years, it was a remarkably good likeness of Captn Coram — In cottages every where were to be seen, the sailor’s farewell & his happy return — youthfull sports, & the feats of Manhood — the bold Archers shooting at a mark — the four Seasons &c — some subjects were of a funny & others of a grave character — I think the last portraits I remember of, were those of some of the Rebel Lords & ‘Duke Willy’ [Cumberland] — these kind of Wood Cut pictures are long since quite gone-out of fashion.15

This valuable account tells us not only about the subjects and techniques of these cheap prints, but also where they were displayed — on cottage and farmhouse walls and in schoolrooms — and thus that they would have been purchased by schoolteachers, cottagers, farmers, and, by extension, their urban equivalents, small tradesmen and their families.

It is clear that the print-makers were largely unknown, even to someone like Bewick at the heart of the print trade, but while those who cut the woodblocks have almost all been forgotten, the publishers responsible for commissioning, printing, advertising, and distributing these prints throughout the country and beyond are known, and some of them became wealthy from selling large numbers of prints at low prices. The leading publishers of cheap prints from the 1730s to the early nineteenth century were the Dicey and the Marshall families in Bow Churchyard and Aldermary Churchyard in the City of London. David Stoker’s study of these closely related businesses reveals the impressive scale of their activity as publishers of ballads, chapbooks, prints, maps, and other cheap printed material.16 In 1736 William Dicey took over the business in Bow Churchyard that had been started by his brother-in-law, John Cluer, at the beginning of the century. William’s son, Cluer Dicey, took responsibility in 1740. By 1755 the Diceys were running a second press in Aldermary Churchyard with Richard Marshall. The Bow Churchyard press ceased publishing a few years later. Marshall seems to have taken over at Aldermary Churchyard on his own in 1770, his son John Marshall succeeding him in 1779, at first in partnership with other members of the family and then from 1789 as sole proprietor.

Two surviving catalogues — the William and Cluer Dicey catalogue of 1754, and the Cluer Dicey and Richard Marshall catalogue of 1764 — provide a large amount of information about their stock, at least at those two dates. They list, respectively, 278 and 333 ‘wood royals’ — that is, pictorial prints measuring about 50 × 40 cm, each of which would have yielded thousands of impressions.17 The wholesale price was 1s. 2d. per quire (twenty-four sheets) — that is, a little more than ½d. each, which suggests that they would probably retail at 1d. plain, and 2d. if coloured (although colourists were paid very little, their work usually doubled the retail price of a print). Subjects ranged from the religious and conventionally moralistic through to the patriotic and the mildly titillating. Among those in the 1764 catalogue that have been identified are The Lord’s Supper (no. 22),18 The Broad and Narrow Way to Heaven and Hell; or, St. Bernard’s Vision (no. 48),19 The Happy Marriage (no. 144),20 The Prodigal Sifted (no. 149),21 King Charles the First on Horseback (no. 253),22 and Fanny Murray (no. 287).23

Another important publishing business selling prints of the middle and cheaper ranges was set up by John Overton at the White Horse without Newgate, half a mile west of Bow Churchyard, shortly after the Great Fire. His son Henry Overton (1676–1751) continued at the same address and left a fortune of £10,000, demonstrating just how lucrative was the trade in selling cheap prints. A second Henry Overton (d. c.1764) took over the business on the death of his uncle and in 1754 issued a 79-page catalogue that included 200 ‘Cheap prints, each printed on a sheet of royal paper’, among which were Thomas Brown, the Valiant Trooper and William, Duke of Cumberland. Two years later he published a short list of coloured ‘wood prints’.24 These prints were not designed for collectors, but one of Overton’s publications — a large stencil-coloured woodcut illustrating A Prospect of the Glorious Action at Dettingen, ‘Coloured and Sold at the White Horse, without Newgate’, published around 1744 — has survived by chance because it was at some point pasted on to a backing sheet and then used as a wrapper for a parcel addressed to ‘Mr Csernatoni, 8 Buckingham Street, Strand’.25

It seems, to judge from the few surviving prints and from Bewick’s Memoir, that large woodcuts enjoyed a period of particular popularity in the middle of the century. Many relate to contemporary events. The military subjects noted above chiefly concern the conflicts of the 1740s: the War of the Austrian Succession and the Jacobite Rebellion. These woodcuts would have been time-consuming, and therefore relatively expensive, to produce, and publishers must have been sure of a large market before commissioning them. A simple etching could be made more quickly of a subject that would only have short-term interest, and the copper-plate could be used again for another print.

Sometimes, however, publishers must have believed that large numbers of prints would sell and that it was worthwhile to have a woodblock cut. Royal scandals always sell. An example that was clearly seen as marketable was John of Gaunt in Love, satirizing the Duke of Cumberland’s infatuation in 1749 with a street musician, a Savoyard hurdy-gurdy player.26 The woodcut copies a 6d. etching in which the enormously fat duke is shown on his knees begging the young woman to come with him to Windsor. Neither the name of the print-maker nor the publisher appears on the prints. It was dangerous to mock the royal family and several print sellers were arrested for selling prints of Cumberland and the Savoyard girl.

Better-known examples of woodcuts based on etchings are two royal-sized prints of 1751 by J. Bell after Hogarth’s Third Stage of Cruelty and Cruelty in Perfection.27 Bell was a highly skilled craftsman who, unusually, signed his work.28 No impressions of woodcuts of the first two subjects in Hogarth’s series are known, and it seems likely that they were never made — perhaps because their publication was not considered financially viable. For the Diceys, Marshalls, and other large-scale publishers, however, it was worthwhile to produce prints in a number of versions, sizes, and price ranges. They would have had craftsmen at hand who could quickly produce simple prints using different techniques, and they would have had a number of presses on their premises for printing either relief or intaglio prints. William and Cluer Dicey’s trade card shows images of two types of press.29

Some subjects were so successful that they appeared over long periods of time in many versions, both cheap and more expensive. Keep within Compass — a moralizing image showing a respectable young man or woman standing beneath a pair of compasses, beyond which are mottoes or vignettes warning of the fates of young people who succumb to excesses — was familiar from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century.30 The Birmingham artist Samuel Lines remembered that in the 1780s the image was ‘a great favourite, and frequently to be seen on the walls of farm-houses and cottages’.31 Examples of the subject in the British Museum include a small print of around 15 × 10 cm, still in a cheap eighteenth-century frame; mezzotints measuring 35 × 25 cm published by Carington Bowles about 1785 at 1s. plain and 2s. coloured; reissues of the same prints from the 1790s or early nineteenth century by Bowles and Carver; a smaller mezzotint published by Carington Bowles about 1785; and a version of about 1820 published by William Darton.32

The Tree of Life is a similar updating of an earlier emblematic image for an eighteenth-century audience. The representation of Christ crucified on a tree at the beginning of the road that leads to the heavenly city had appeared in many contexts for over a century, but around 1760 a street scene appears in front of the tree. Men and women are drinking together and indulging in ‘Chambering & Wantonness’, ignoring both the mouth of hell to one side and the preachers — in some versions identifiable as John Wesley and George Whitefield — who urge them to turn towards Christ.33 The first version seems to have been published by Thomas Kitchin, best known as a cartographer, as a fine royal-sized etching. The figure of Christ is added to the tree in a version that, to judge by the women’s costumes, must date from the 1770s (the publisher is unknown). Carington Bowles published his version at the same time, and it was still being reissued by Bowles and Carver at the end of the century. In 1793 John Evans published a simpler etching in reverse, and in 1804 George Thompson published a crudely etched version of Evans’s print, which must have sold extremely cheaply. In 1825 James Catnach produced a woodcut based on the Bowles version.34

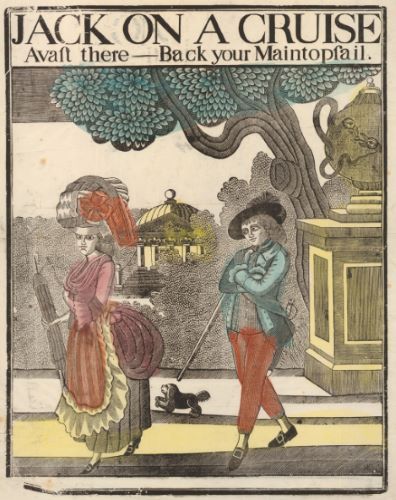

Repetitive prints of varying quality were not confined to moralizing subjects. There is always a market for light-hearted images of the relations between the sexes, and in the eighteenth century these often focused on sailors home from the sea and ready to spend their cash on women of easy virtue. Robert Sayer of Fleet Street is not known for dealing with the very cheapest prints, but he published large numbers of the 6d. or 1s. variety, and some of these could be copied at a lower price. An example is a pair entitled Jack on a Cruise and Jack Got Safe into Port with his Prize, of which he published at least three versions around 1780. They show, in the first of the pair, a sailor following a fashionably dressed young woman in a park, and, in the second, the couple sitting side by side on a sofa.

The prime examples must be a finely etched pair of prints, measuring 24 × 18 cm, where in the first scene the sailor leers and the young woman smiles coyly, while in the second scene both take on hesitant expressions as the sailor places his hand at her breast. A pair of rapidly produced mezzotints, published in November 1780 in the standard size for 1s. prints of 35 × 25 cm are far less detailed and pay little attention to the characterization of the figures. These were followed by a pair of small (15 × 11 cm) mezzotints dated 1786, which probably retailed at 6d. each. They sold in such numbers that the copper became worn and some etched lines needed to be added to strengthen the images. The subjects also appeared as large, crudely coloured relief prints measuring about 50 × 38 cm, probably intended to be displayed on the tavern walls (Figs 3.6 and 3.7). They are not printed from woodblocks but from soft metal, probably pewter, plates that could be cut and stamped quickly to create decorative surfaces. Surviving prints from pewter are rare and the softness of the metal may have prevented it from yielding many impressions.35 The first of the two images, Jack on a Cruise, was sufficiently popular for the sailor and the young woman to appear as a pair of contemporary pearlware plaques and also on several of the transfer-printed mugs that began to be produced very cheaply in the Midlands at the end of the century, using newly developed factory techniques.36

Other copies of prints would have been made in order to save the expense of a new design. Portrait prints were often simply given new titles so that they could serve to represent someone else whose image had become more saleable. A portrait of an extraordinarily fat man appears in a large etching of the procession of the Dunmow Flitch, etched by Charles Mosely in 1752 after a painting by David Ogborne, a local artist, who may have published the print himself. At least three prints of the same man, in reverse, were published two or three years later as Jacob Powell, an Essex butcher, who had died in October 1754 weighing 560 lb. In 1755 he appeared in a woodcut on a 3d. broadside as ‘Christopher Bullock, Watch and Clock-maker, in Bottesdale, in the County of Suffolk’.37

As well as new subjects, older prints were still being reissued. The William and Cluer Dicey catalogue of 1754 refers to ‘lately purchased, the Stock of several Printsellers deceased’. These would have included copper-plates from the major seventeenth-century publisher Robert Walton (1618–88), at least part of whose stock passed after his death to Christopher Browne, then to George Wildey, then to John Cluer. This provenance is certain for one Dicey copper-plate, The Prodigal Sifted (no. 117, in the 1764 catalogue), an etching measuring about 19 × 30 cm, which was published in July 1677 and described in the Term Catalogues as ‘The Prodigal Sifted; or The lewd Life and lamentable End of Idle, profuse, and extravagant, persons, Emblematically set forth, and described for a warning to unexperienced Youth […] Price, black and white, 3d.; and coloured, 6d. Sold by R. Walton at the Globe and Compasses in St. Paul’s Churchyard’.38 By the time the plate was acquired by William Dicey it was worn and would have looked old-fashioned enough to appeal only to a less discriminating market, no doubt at a lower price than 3d. or 6d. He left Walton’s publication line in place and simply added his own, ‘now sold by W. Dicey in Bow-Church-Yard, Cheapside, London’.

The same composition also appears in an Aldermary Churchyard woodcut, The Prodigal Sifted, which clearly dates back to the seventeenth century (no. 149, in the 1764 catalogue). Walton does not seem to have produced woodcuts, and that block must have come from another source, as must The Happy Marriage (no. 144, in the 1764 catalogue) where husband and wife are dressed in costumes of the 1690s. Another large woodcut published in Aldermary Churchyard was clearly of sixteenth-century origin, to judge by the costumes of the women shown. It is known in two impressions. The earlier, titled The Several Places Where You May Hear News, the publisher of which is unknown, was in the collection of Samuel Pepys and therefore dates from before 1700.39 By the time the Aldermary Churchyard impression was printed, however, the block was damaged and the title changed to Tittle Tattle; or, The Several Branches of Gossipping.40

A publisher of large woodcuts from whose stock the Diceys or Marshalls acquired at least one woodblock was George Minnikin, who traded at various City of London addresses in the late seventeenth century. Minnikin’s name appears on an impression of a grand woodcut of William the Conqueror, its style suggesting that it had been cut originally in sixteenth-century Germany, probably representing a quite different warrior.41 By the time an impression was printed in Aldermary Churchyard the title had been changed to Saint George, the Chief Champion of England and appropriately patriotic verses had been added in letterpress.42 These examples indicate that woodblocks could be used over as much as 200 years, although the quality of late impressions is very poor and therefore they would sell cheaply into an undemanding market.

While woodblocks can suffer from cracking and worm infestation, copper-plates wear down from pressure during printing and finer lines gradually disappear, sometimes being replaced with coarser working. Although collectors and connoisseurs disdain such late impressions, declining quality did not matter at the bottom end of the trade, where purchasers were interested in the image rather than in the quality of the print itself. An example that demonstrates this point is a fine portrait by Robert White (1645–1703), the most admired British engraver of his time. His copper-plate of Kaid Muhammed Ben Hadu Ottur, Moroccan ambassador to Britain, made in 1682, remained in print — although as a shadow of its former self — seventy or eighty years after it was made. By 1764 it had found its way to Aldermary Churchyard (‘fools-cap sheet prints’, no. 67, in the 1764 catalogue) and was printed with the added publication line ‘C. Dicey & Co.’ A comparison of early and late impressions in the British Museum is an object lesson in the deterioration of copper-plates through wear and tear on the press.43 White’s copper-plates passed through his son to John King at the Globe in the Poultry, and then to his son, also John King, whose stock was sold posthumously at Langford’s, Covent Garden, in January 1760. It may have been at that sale that Dicey acquired the plate of the Moroccan ambassador. The plate of a portrait of Archbishop John Sharp (1645–1714) by Robert White, published by C. Dicey & Co. in Aldermary Churchyard (‘fools-cap sheet prints’, no. 59, in the 1764 catalogue) was probably acquired at the same time.44 Both would have been marketable subjects. The image of the exotic and handsome ambassador would always find sales, and portraits of clergy enjoyed great popularity in the eighteenth century, as demonstrated by the well-known mezzotints of Carington Bowles’s print-shop window in St Paul’s Churchyard with its line of portraits of preachers on display.45

The price of the Dicey/Marshall ‘fools-cap sheet prints’ was little more than that of the ‘wood royals’. The 1764 catalogue includes seventy-one ‘fools-cap sheet prints’ for sale wholesale by the quire at 1s. 5d. plain and 3s. coloured. More than 400 larger ‘copper royals’ sold wholesale by the quire at 2s. plain, 4s. coloured, or 6s. spangled, while 145 smaller ‘pott sheets’ sold at 1s. per quire plain and 2s. coloured. Subjects covered the same range as the woodcuts. Besides royal, foolscap, and pott prints, which are listed individually, others were simply described as groups: ‘Four Hundred different Kinds of Prints, Each on a Quarter of a Sheet of Royal Paper; as Scripture Pieces, Views, Horses, Heads, and other merry Designs’ were offered wholesale at 2s. plain and 4s. coloured for 104 prints (four quires), while cheapest of all were ‘Three Hundred different Sorts of Lotteries, Pictures for Children, as Men, Women, Kings, Queens, Birds, Beasts, Horses, Flowers, Butterflies, &c. Each on Half a Sheet of good Paper’ selling wholesale at 1s. 8d. plain and 3s. 4d. coloured for 104 prints.

‘Lotteries’ were sheets of small images that appear in print publishers’ catalogues throughout the century: Henry Overton’s in 1717 included ‘About 500 more several sorts of small plates for children to play with, both coloured and plain’, and Carington Bowles in 1786 offered ‘400 different sorts […] intended to divert and instruct children in their most tender years’ at 1s. 10d. per 100 plain and 3s. 8d. coloured. A favourite game involved pushing a pin into a book containing lottery prints: the child who pushed the pin into an opening containing a print would get to keep it. It seems unlikely that poor families would be able to buy prints for their children to play with, but like other cheap goods they might be a means of earning a little money on the streets. Girls in Glasgow (and perhaps elsewhere) were said to use the ‘picture book’ game to importune passers-by.46

Two types of cheap prints dominated the late years of the century: one with political aims, the other as a solution to practical demands. The Cheap Repository for Moral and Religious Tracts was set up in the 1790s to publish ballads and chapbooks neatly illustrated with small woodcuts. It was subsidized by supporters who believed that evangelical propaganda might prevent the spread of radical ideas in the years after the French Revolution. The subsidies undercut the selling price of commercially published material, and for a period John Marshall, John Evans, and others in the cheap print trade switched much of their effort to work for the Repository.47

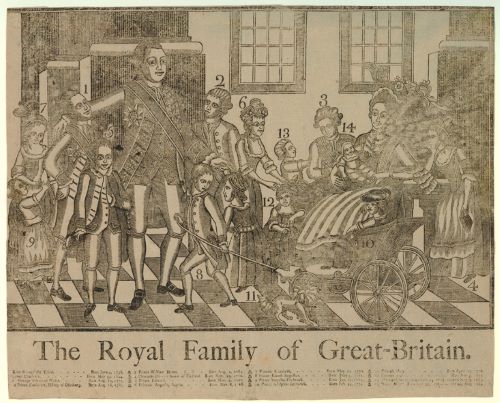

In contrast to the small, neat Cheap Repository publications, the publishers of cheap prints produced an increasing number of large etchings of both topical and traditional subjects from the 1780s onwards. The old, large woodblocks that had been in use for more than a century would have deteriorated so much that they could no longer produce prints of any value. The time taken to cut new blocks would only have been worthwhile for prints that were sure to sell in large numbers; an example is The Royal Family of Great-Britain, which must date from after 3 May 1783 since it records the death of Prince Octavius at the age of four on that day (Fig. 3.8).

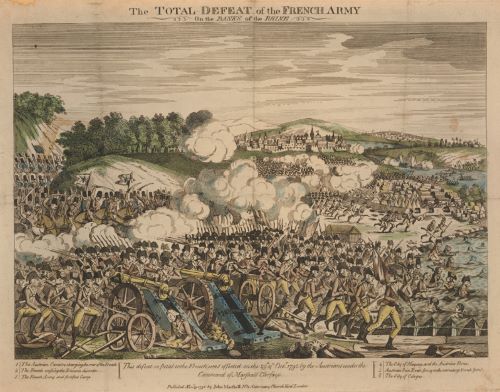

Etchings could be made swiftly and, if the outlines were deep, could produce large numbers of prints. A group of twenty etchings published by John Evans in 1793 and 1794 illustrate typical subjects: traditional moralizing and religious images and narratives, such as The World Turned Upside Down, The Various Ages and Degrees of Human Life, The Prodigal Son, etc., but also topical subjects concerning the campaign for the abolition of slavery, the death of Jean Marat and execution of Charlotte Corday, and the British fleet preparing to set sail under Earl Howe in 1794.48 Prints relating to the ongoing wars were popular. On 19 November 1795 John Marshall published an etching measuring 36 × 47 cm of The Total Defeat of the French Army on the Banks of the Rhine, which had been rapidly produced to celebrate the battle of Mainz only three weeks before, with a caption describing (optimistically) ‘This defeat so fatal to the French’ (Fig. 3.9). In June 1800 George Thompson published The Storming and Taking of Serringpatam [sic], a double-sheet etching measuring 58 × 93 cm, showing the death of Tipu Sultan in the attack in the aftermath of which the East India Company took over the kingdom of Mysore.49 Large prints of this type would provide appropriate decoration for taverns and other masculine contexts. An example from before the middle of the century, A Midnight Modern Conversation (an enlarged version of Hogarth’s print, published by John Bowles and measuring 57 × 87 cm), must surely have been intended for a drinking room.50

Although the subject matter of cheap pictorial prints remained largely unchanged, technological developments and the public appetite for novel designs brought about drastic changes in the early years of the nineteenth century. Transformations came with the introduction of the iron press, improvements in paper production, and the development of commercial stereotyping. In the second decade of the new century James Catnach made creative use of all these innovations to produce a new type of print that combined image and text with bold and varied type, all printed at a very low price on smooth, lightweight paper. Before long, lithography allowed the production of huge numbers of prints at vastly reduced prices. The type of cheap pictorial print familiar in the eighteenth century was soon of interest only to antiquarians, while poorer citizens could at last purchase printed images in the streets for 1d. or less.

Endnotes

- This essay has allowed me to revisit my work of more than twenty years ago on cheap prints in England, in Sheila O’Connell, The Popular Print in England, 1550–1850 (London: British Museum Press, 1999), and to incorporate some of my own further thoughts as well as research in the field by others — in particular, David Stoker’s important study of the Dicey/Marshall publications (n. 16 below). I have also taken the opportunity to refer to cheap prints acquired by the British Museum since 1999.

- Marcellus Laroon’s A Merry New Song (1689) is one of the best-known early images of a street vendor of illustrated ballads.

- Examples are Thomas Bewick’s endpieces at London, British Museum, 1860,0811.181, 1860,0811.246, 1860,0811.277, 1860,0811.331.

- London, British Library, Add. MS 16922.

- David Atkinson, ‘Bellman’s Sheets – Between Street Literature and Ephemera’, in Transient Print: Essays in the History of Printed Ephemera, ed. Lisa Peters and Elaine Jackson (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2023), pp. 107–29.

- London, British Museum, 1872,0608.545, Heal,76.19.

- Mr Becket, trunk-maker, at No. 31, Haymarket, exhibited a number of curiosities in the 1780s. Tickets collected by Sarah Sophia Banks are at London, British Library, L.R.301.h.5. Her brother, the eminent naturalist Joseph Banks, owned similar tickets now in London, British Museum (nos. beginning 1914,0520).

- W. S. Lewis (ed.), The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, vol. 20 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960), p. 199.

- Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery, NG 838.

- Hall was hanged at the end of Catherine Street, The Strand, London, on 14 September 1741. For the prison chaplain’s account, see Proceedings of the Old Bailey, OA17410914.

- London, British Museum, 1850,0713.177.

- London, British Museum, Y,1.139, 1882,0812.459.

- London, Tate Gallery, T07594; reproduced as The Young Maid & the Old Sailor in a stipple engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi, published by Robert Wilkinson, 1785 (London, British Museum, 1868,0808.2890), and as The Pretty Maid Buying a Lovesong, a mezzotint by John Raphael Smith, published by Carington Bowles, 1780 (London, British Museum, 1874,1010.22, 1935,0522.2.74). Part of a print of General Howe’s brother, Admiral Richard Howe, can also be seen in the painting.

- Trade cards have been collected both for their attractive designs and as sources of information about small-scale manufacturing and business practices. There are important collections in the British Museum (largely two groups assembled by Sarah Sophia Banks (1744–1818) and Ambrose Heal (1872–1959)), the Bodleian Library’s John Johnson collection, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Portrait print collections in the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery include examples of eighteenth-century cheap prints.

- A Memoir of Thomas Bewick, Written by Himself, ed. Iain Bain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), pp. 192–93 (punctuation and spelling as transcribed in Bain’s edition). For identifications of the subjects described by Bewick, see O’Connell, Popular Print, p. 88 and figs 4.19 and 4.20. Bewick’s own copy of King Charles’s ‘twelve good rules’ survives in a private collection in London and is promised to Bewick’s birthplace at Cherryburn (National Trust).

- David Stoker, ‘Another Look at the Dicey-Marshall Publications, 1736–1806’, The Library, 7th ser., 15 (2014), 111–57.

- Sizes given in the catalogues refer to the sheet rather than the print itself, which would be several centimetres smaller. Prints were often printed two to a sheet.

- London, British Museum, 1858,1209.1.

- London, British Museum, 1858,1209.2.

- London, British Museum, 1872,1214.383; London, Victoria & Albert Museum, E.300-1986 (a coloured version).

- London, British Museum, 1858,1209.5.

- London, British Museum, 1862,1008.205.

- London, British Library, HS.74/1659. See O’Connell, Popular Print, p. 59 fig. 3.15. Woodcuts published by Dicey/Marshall in the British Museum collection are reproduced in that book and in the British Museum database https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection.

- Two-page ‘Catalogue of Wood Prints […] Colour’d and Sold by Henry Overton’, appended to Charles Snell, The Standard Rules of the Round Text Hands (1756); recorded in A. Griffiths, ‘A Checklist of Catalogues of British Print Publishers, c.1650–1830’, Print Quarterly, 1.1 (1984), 4–22.

- London, British Museum, 1998,1108.63.

- London, British Museum, J,1.63, 1868,0808.12399. For a full account of the scandal, see Elizabeth Einberg, William Hogarth: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2016), pp. 301–03.

- London, British Museum, 1860,0728.63, Cc,2.169, Cc,2.171.

- For other examples of Bell’s woodcuts, see O’Connell, Popular Print, p. 65.

- London, British Museum, Heal,59.56.

- The image seems to derive from the title page of Keepe within Compasse; or, The Worthy Legacy of a Wise Father to his Beloved Sonne, published by John Trundle in 1619.

- A Few Incidents in the Life of Samuel Lines, Sen. (Birmingham, 1862), p. 10.

- London, British Museum, 1999,0328.1, 1902,1011.7994.+, 1935,0522.3.62, 1935,0522.3.63, 2010,7081.1879, 2009,7111.1.

- For related images, see O’Connell, Popular Print, pp. 72, 228 nn. 11–20.

- London, British Museum, 1906,0823.40, 1868,0808.4623, 1868,0808.4624, 1935,0522.3.51, 1992,0620.3.16, 2000,0930.43, 1992,0125.32.

- London, British Museum, 1861,0518.941 and 942, 2010,7081.1178 and 1175, 2010,7081.1885 and 1884, 2011,7084. 20 and 19.

- The plaques were offered online by 1stDibs in August 2020. Among several examples of the mugs is one sold at Lyon & Turnbull on 23 March 2005. For popular imagery on transfer-printed pottery, see David Drakard, Printed English Pottery: History and Humour in the Reign of George III, 1760–1820 (London: Jonathan Horne, 1992).

- The images of Jacob Powell are a 6d. etching by Charles Spooner, published by J. Swan of Charing Cross (London, British Museum, 1851,0308.532), a small mezzotint by John Jones (London, British Museum, 1851,0308.533, 1902,1011.2911, 1902,1011.2912), and an etched illustration for the Universal Magazine by Anthony Walker (London, British Museum, 1875,0612.520, 1948,0214.44; Heal,Portraits.59). The broadside is The Suffolk Wonder; or, The Pleasant, Facetious and Merry Dwarf of Bottesdale (London, British Museum, 1851,0308.63).

- London, British Museum, 1870,1008.2897; Edward Arber (ed.), The Term Catalogues, 1668–1709 A.D., with a Number for Easter Term, 1711 A.D., 3 vols (London: Edward Arber, 1903–06), I, 282–83.

- A. W. Aspital, Catalogue of the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, vol. III, Prints and Drawings, part i, General (Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1981), p. 35, chapter IX, no. 442.

- London, British Museum, 1973,u.216. The composition itself goes back to a sixteenth-century French etching, Le Caquet des femmes (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Tf.2,fol.49), which was also used as the basis for an etching by Wenceslaus Hollar (London, British Museum, Q,4.132, 1880,0710.863).

- The impression is in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (information from Malcolm Jones).

- London, British Museum, 1858,1209.3.

- London, British Museum, 1849,0315.97, 1982,U.1986.

- ondon, National Portrait Gallery, D20988 (cited in Stoker, ‘Another Look at the Dicey-Marshall Publications’, p. 125).

- Spectators at a Print-Shop in St. Paul’s Church Yard, 1774 (London, British Museum, 1877,1013.849, 1880,1113.3311, 1935,0522.1.16, Heal,Portraits.306, 2010,7081.379); A Real Scene in St Pauls Church Yard, on a Windy Day (London, British Museum, 1880,1113.3312, 1935,0522.1.30).

- S. Roscoe and R. A. Brimmell, James Lumsden & Son of Glasgow: Their Juvenile Books and Chapbooks (Pinner: Private Libraries Association, 1981), p. xv.

- For detailed accounts of the Cheap Repository, see G. H. Spinney, ‘Cheap Repository Tracts: Hazard and Marshall Edition’, The Library, 4th ser., 20 (1939), 295–340; David Stoker, ‘John Marshall, John Evans, and the Cheap Repository Tracts’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 107 (2013), 90–102.

- London, British Museum, 1992,0620.3.1–1992,0620.3.20.

- London, British Museum, 2019,7040.1

- London, British Museum, 1860,0623.80. The large numbers of unauthorized — and cheap — copies after Hogarth’s print encouraged his determination to obtain copyright for designers of prints, which resulted in the passing of ‘Hogarth’s Act’ in 1735.

Chapter 3: Pictures on the Street: Cheap Pictorial Prints in Eighteenth-Century Britain, from Cheap Print and Street Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century, edited by David Atkinson and Steve Roud, published by Open Book Publishers, 09.04.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International license.