Making sense of two of the ways in which love was organized in classical Greece.

By Oana Uiorean

Department of Sociology

Goldsmiths

University of London

Abstract

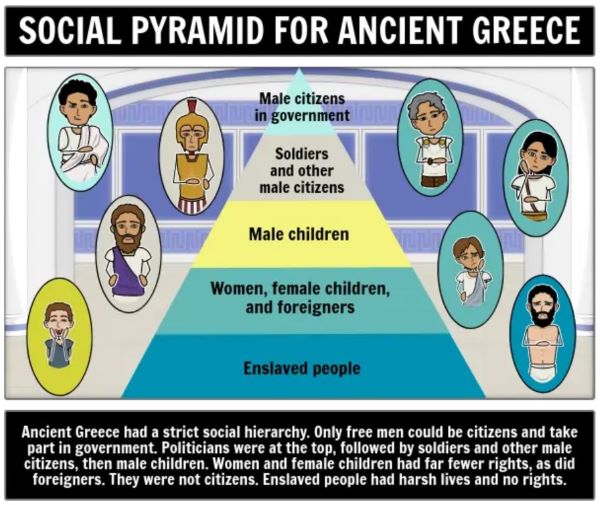

This paper proposes a re-reading of Plato’s Symposium through the lens of class theory and materialist feminism. I argue that the speeches contained in the text, and particularly the one delivered by Pausanias, outline a system of social closure designed to pass on privilege between worthy upper-class males in classical Greece, and at the same time to dominate women and keep them in their segregated place in order to exploit their labor for the biological and social reproduction of this class. Within this system, Love (with a capital L) played the role of organizing principle. The way in which love was expected to be offered or withheld structured the reproduction of the society Plato’s characters inhabited. I will argue that the result is a system of gender-based oppression that has undergone few essential changes across millennia and that endures under contemporary capitalism. Homoerotic love no longer plays the role of medium for the passing on of privilege and the adjacent domination of women. That territory is now occupied by heterosexual love, with the social attitudes and beliefs attached to it acting directly towards the oppression of women instead. This is done specifically through household and kinship relations. These are imposed on women through various coercive and cultural instruments, with the aim of appropriating their labor to support the production of surplus. Classical Greece upheld a protomodel of what we observe in contemporary configurations. It is important to recognize the constancy of gender oppression predicated on social reproduction in order to develop a gendered counterhistory of capitalism.

Introduction

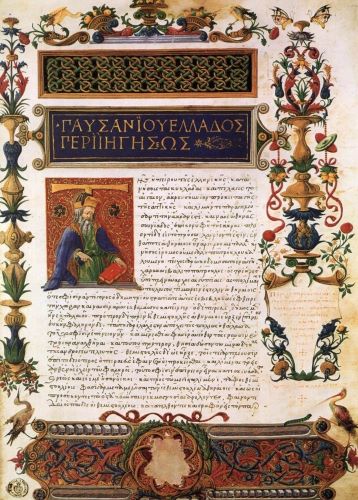

I propose a radical re-reading of certain aspects of Plato’s Symposium, arguably one of the best-known texts on the nature of love. The Symposium is generally interpreted as an analysis of eros, or passionate love and desire1: this desire is not limited to sex, but, incited by beauty, may have as object not only other people but also food or war. The focus in Symposium is primarily on the experience of the one desiring, rather than the reciprocity of feeling that may or may not take place.2

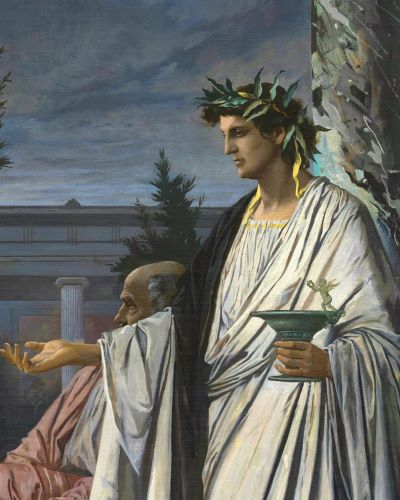

The title of the text refers to what was essentially a drinking party for men. In Plato’s story, a number of upper-class Greek men come together for a party in 416 BC and decide to eulogize love, and specifically eros, that is, to take turns at giving speeches on the wonders of love and how one should go about fulfilling its demands. It must be noted that men belonging to this class led a life of leisure. They did not have to work for a living and were financially comfortable. As a consequence, they valued the loftier realms of wisdom and knowledge, aimed to perfect themselves in their practice, and rather disdained material ambitions.3

The question of eros involved a consideration of homoeroticism, which was an established practice at the time, mainly in the upper classes. The term cannot be equated with homosexuality, as most of those who indulged in homoeroticism did not have an exclusive preference for partners of the same sex. In fact, most were married to women. However, women, especially in the upper classes, were kept segregated, considered inferior and not worthy of true love, and thus many of the men had simultaneous and often more profound relationships with boys.4 In these relationships, the older man, the erastai, would pursue a young boy chosen for his physical beauty and potential for virtue.5 Once the boy agreed to enter into a relationship with the older man, he was expected to remain passive and allow himself to be dominated. He would not reciprocate the sexual desire, but may eventually feel philia, or a friendly affection, for the older lover, who in turn would take on the shaping of the young boy’s character through the passing on of knowledge and wisdom.6 This is in fact the focus of the symposium described by Plato. Even though the declared objective is to think about love in general, the men in Plato’s text spend most of their time on the particularities of relationships between grown men and adolescent boys, and specifically the mutually beneficial exchange of “pederasteia for philosophia”.7 Such relationships were primarily educational in nature and played a specific social function.8

In this paper, I will apply class theory and feminist historical materialism to make sense of two of the ways in which love was organized in classical Greece. Of interest is, on the one hand, what Foucault calls the stylization of erotic conduct,9 or specifically, the aforementioned relations between grown men and boys. To this end, I will pay particular attention to Pausanias’ prescriptivist speech in Symposium. This speech claims to outline a view of eros as a dual phenomenon, consisting of a proper way to love and an improper one. Sheffield maintains that Plato’s goal in the text isn’t to give an account of interpersonal love, but rather to consider “the desire for good things and happiness”.10 Taking my cue from Sheffield, but departing from her subsequent argument, I will claim that the speech actually describes a system of Weberian social closure designed to pass on privilege within a specific class, the one encompassing free, educated, and wealthy adult males. On the other hand, I will look at the status of women as wives attached to this social class during the same period, and argue that the parallel structure of matrimony, which also relied on mechanisms of social closure, had the goal of reinforcing relations of domination as described in Marxist class theory. To finish, I will integrate the two phenomena to show how their interaction establishes a structure essential for social domination, particularly that of women as reproducers.

Feminist historical materialism, which takes gender differentiation to be a core attribute of a specific historical social formation and focuses on the central category of the gender division of labor, is very useful to this end.11 I will analyze in conjunction the structure of the relationships of male adults with young boys on the one hand and with women as wives on the other to support my claim that at stake in the way classical Greek society organized love are the class structure and power relations within it, rather than the mere cultural stylization of sexuality with the intention to constitute what Foucault refers to as “an aesthetics of existence”.12

In what follows, after a brief overview of class theory from the points of view of Weber and Marx, I will take a detailed look at Plato’s text to identify the elements that show how prescriptivism in matters of love was used to organize society and pass on privilege. I will then turn to the condition of women during the same period, and end with a reflection on the continuity to this day of women’s oppression predicated on the appropriation of the unwaged ‘labor of love’ supplied by women.

Class

There are several ways to describe what class is. For the purposes of this paper, I will focus on two. The one put forth by Weber, also referred to as the opportunity-hoarding approach, focuses on institutional aspects and the way in which social positions give some people control over economic resources while excluding others from access to those same resources. The one suggested by Marx and developed by his followers, also called the domination and exploitation approach, looks at the way in which economic positions give some people control over the lives and activities of others.13

The central concept in Weberian class theory is that of social closure. It describes the system through which strict requirements are set in place for access to a certain class. These requirements include private property rights, educational credentials, citizenship rights, gender-based restrictions, etc. The advantages of the elites are intrinsically linked to the disadvantages of those excluded. It is thus essential for the exclusion to be guaranteed through some form of institutionalization in order to preserve privilege. Opportunities are therefore hoarded by an elite at the expense of those kept outside its ranks.14

Marxist class theory, while recognizing the forces of social closure, is centered on domination and exploitation as ways in which some people control the lives of others. Domination is the ability to control the activities of others, while exploitation means acquiring economic benefits from the labor of those dominated. Exploitation requires domination. In other words, Marxist theory goes beyond the Weberian preoccupation with restricted access. It adds to it the important dimension of control over the labor of another to one’s own advantage as a key element of class structure. The focus is on structured inequality that is constituted through the cooperation between exploiters and exploited as well as dominators and dominated.15

The two approaches are complementary in describing the reality of class generated by their interaction and particularly the importance of power and social rules. Opportunity hoarding works to reinforce exclusion for purposes of sustaining and reproducing privilege in the way adolescent boys in classical Greece went on to enjoy in adulthood the knowledge and social protection offered by their former sexual partners and, by extension, mentors. Through mechanisms of supervision, monitoring, and sanctions used to enforce what was ultimately labor discipline, exploitation and domination maintained the fundamental division between upper-class Greek males as holders of privilege, specifically economic power buttressed by exclusive juridical and political rights, and females as key social reproducers of this privilege. As we will see below, the basis of this dynamics was the strict segregation and ultimate isolation of women, as well as the fact that they were prevented from owning property.16

The Party

As mentioned above, the task proposed by the host, Agathon, to the men attending his party was to produce a eulogy of eros. Although he is not the first speaker, Pausanias begins his speech by redefining the topic of the symposium.17 His central claim is that love needs to be regulated before it is able to achieve its aim. For Pausanias, love done properly brings order to the world, rather than merely producing pleasure or fulfilling a fleeting need. He takes issue with the request to praise Love without qualification, and continues by making a distinction between two types of love, Common and Celestial. The two types of love are said to have two different domains. One ensures that love is done properly, and one doesn’t. One type of love, Celestial Love, merits praise, and the other, Common Love, merits disdain.18 Pausanias repeatedly emphasizes the fact that there is a proper way to do things and an improper one, and that the difference between the two should be the focus of any consideration of love.

Not surprisingly, in Pausanias’ description Common Love is experienced by ordinary people. Such people are not sufficiently discerning, because they love both women and boys and do so for the body and not the mind. Their goal is merely to satisfy their desires, without care for whether this is done properly. On the other hand, Celestial Love gives rise to affection for strength and intelligence, which, in Pausanias’ view, are attributes reserved to the male.19 This is, Pausanias underlines, the only proper way to love.20 The outline of a system of social closure already takes shape, marked by what is arbitrarily seen as acceptable, or proper, behavior, and what is not.

Even among those who love boys, only some are truly inspired by Celestial Love. This further distinction depends on the boy’s age.21 Pausanias feels a restriction in this regard is essential to ensure a lasting relationship rather than a fleeting one that fools the boy and provides him with no long-term advantages. From the older man’s point of view, a relationship with a boy is an investment, so it is necessary for a man to choose his young lover based on the latter’s likelihood of turning out well. In other words, the boy should not be too young, but rather old enough to make possible the assessment of budding qualities.22 Pausanias even calls for a rule to be formulated and imposed in this regard, which he compares to methods used to prevent liaisons with women.23 This type of prevention, as we will see below, isn’t merely a question of style, but it is also essential for consolidating women’s oppression for purposes of protecting male privilege.

Pausanias proves he is aware of the power of love to organize societies. He shows how love, necessarily between two men, underlies organized resistance, and he refers to the loyalty and friendship it gives rise to as something that tyrants see as a threat to their power.24 He makes historical references to Athenian tyrants toppled by the collaboration between two lovers, and to the fact that Ionians and other peoples in the Persian empire, ruled by tyrants, qualify love, or rather the gratification of a lover, as wrong, because it isn’t in the interest of those holding power to allow such closeness between men to lead to counter forces arising and organizing.25

The essence of the relationship between a boy and his lover is not intended to be unequal, the way it is between a man and his future wife. The boyfriend is expected to evolve to a status/virtue equal to that of his lover, through learning and being guided by the latter.26 As a consequence, courtship is also subject to strict rules meant to test the prospective lover.27 Here too, Pausanias confirms his prescriptivist impulses.

Most of Pausanias’ speech revolves around the distinction between what constitutes a good or a bad relationship. The focus is on the nature of the lover, which in turn will dictate the nature, and, crucially, the outcome, of the relationship. If the lover is of the common type, he is not suitable. He loves the body at the expense of the mind, and thus isn’t constant, and, implicitly, not a solid investment for the future. In other words, he will not become the kind of mentor and lifelong protector a young boy needs as he advances through society and life. Conversely, a lover is good, and hence the relationship is good, if he appreciates character and is thus likely to be constant in his presence, facilitating the boy’s intellectual and social progress well beyond the end of the love relationship. In fact, society has put in place tests to establish the worth of lovers, by encouraging them to prove their commitment and inclination towards constancy.28 They are expected to chase the boys, and the boys to run away and keep up the ritual until character is revealed satisfactorily. Immediate submission is penalized and shamed. These rules are imposed by convention and moral codes. There are also rules applying to the boy. Only one type of lover gratification is good, and that is the one that aims at some sort of personal improvement, such as, for example, increasing knowledge. Mere pleasure is not considered a sufficient reason to yield to a lover, but neither are the lover’s money or political success, as they are bound to be ephemeral.29

Pausanias places great emphasis on the capacity of rules, and of compliance with them, to lead to a good relationship and allow grown man and young boy to avoid ending up in a relationship that is bad, in its outcome or promise for the future, for one of them, or for both. However, it doesn’t follow from Pausanias’ speech that a relationship can be simultaneously bad for both those involved. If the lover fails to follow the moral code, for example by being inconstant in his choices, then the boyfriend loses, because he has missed the opportunity to have an older man’s protection once he becomes an adult and must navigate society and gain status and a position on his own. If the boyfriend flaunts convention, then the lover has invested in a boy who fails to become a worthy man and take forth his legacy.30 Thus, Pausanias outlines a system of passing on advantages, status, and hence privilege that focuses on the nature of the participants but from the point of view of their capacity to follow the rules of the game, much in the vein of Weber’s theory of class. Ultimately, love in Pausanias understanding is a transaction. An exchange of worthy goods for the mutual benefit of the two men involved.31

There are echoes of similar preoccupations in the other speeches as well. For example, Phaedrus claims that the “greatest benefit” that a young man can encounter in his youth is that of a “virtuous lover” to guide him through life,32 thus again emphasizing the importance of a love relationship between equals as a way to order society and ultimately pass on status. Equality here refers to potential and likely outcome, rather than point of departure. Women could never achieve the same level of virtue and depth of wisdom as men. Their bodies were considered to be “fundamentally different and inferior to men’s”, particularly due to their reproductive function, which in turn was considered the main influence on their “physical and mental disposition”.33 A bit further, Phaedrus goes on to claim that this man-boy relationship is a source of power and moral cross-check, allowing men united in one to “conquer the whole world” while also “competing with one another in avoiding any kind of shameful act”.34 He closes by underlining that a boy’s surrender is rewarded by the appreciation of the gods, arguably the highest of praises.35

Eryximachus, speaking as a practitioner of the art of medicine, remarks that he has noticed how love pervades “every aspect of the lives of men and gods”.36 In other words, here, too, love is a structural element. Eryximachus echoes Pausanias’ view on the rightness of gratifying good people and the wrongness of gratifying bad people, and extends it to body parts, classifying them into good, i.e. healthy, and bad, i.e., diseased, and thus worthy and not worthy, respectively, of being gratified.37 Moderation, as manifested in virtue, restraint, and moral behavior, is good, and the province of Celestial Love, and should be passed on to others and reproduced, while self-indulgence is not good, and is governed by Common Love.38 By insisting on defining goodness and emphasizing the need for it to be reproduced at the expense of badness within the strict confinements of that definition, both Pausanias and Eryximachus are in fact aiming for the reproduction of their own types, that is, their own class, and the suppression of any other sort of profiles as inferior and thus destined to be dominated and controlled.

Aristophanes expands the list of virtues to include manliness. It is the very manly boys that stand out already in childhood who later on will be attracted to other men, rather than women, and who will prove their qualities as adults. Interestingly, the way this proof will come about is that “they [will be] the only men who end up in government”.39 This is because homoeroticism and politics were mainly upper-class preoccupations.40 But, also, those engaging in homoerotic relationships were the only ones to end up in government because relationships with older men were elements of the system through which positions were passed on.

Agathon, too, sees love as a vehicle of peace in society, or, in other words, as an organizing principle that brings order to chaos by neutralizing necessity, the source of all that was bad. To support his claim, he gives the example of the “castration and imprisonment” that were typical for the deeds of the gods, and adds that those could never have taken place had they been guided by Love.41 Agathon’s speech is the one that formulates in most detail the clear bias for youth that Love is expected to manifest.42 This furthers the argument that love is a signpost for societal organization. Love is expected to choose the young as his preferred medium, and thus fulfil his role of bridge and relay between generations.

Diotima, in Socrates’ retelling, demotes Love from the status of god to that of spirit, underlining his nature of mediator between the perfection of gods and the imperfection of humans, combining the characteristics of his two parents, Plenty and Poverty, and situates him between wisdom and ignorance.43 Diotima narrows the focus of the previous speeches to the question of reproduction. She claims the only purpose of love is “physical and mental procreation in an attractive medium”.44 Procreation is the path to immortality, which allows the “permanent possession of goodness”.45 Women are acknowledged as playing a role in this arrangement, but an inferior one. Women produce children, albeit their role is merely that of vessels. However, human children are an imperfect path to immortality. They are far less fulfilling than mental procreation, and indeed fame and status, which remain the province of men.46 Men looking for mental procreation will choose a beautiful and virtuous mind to help them release their mental pregnancy. This mind is necessarily male, since women were not viewed in 5th century BC Greece as able practitioners of intellectual pursuits. A woman could have neither wisdom, nor virtue, and thus could never be the vehicle towards eudaimonia (happiness in the Aristotelian sense), which is the highest pursuit in life.47 And, once this fellow virtuous mind has been identified and settled upon, the mentally pregnant man will “take on this person’s education”.48 This relationship is, in Diotima’s view, far more powerful and stable than one between people who share only “ordinary children”, in other words, between a man and a woman.49 Human children are, in general, less desirable than children of the mind, as the latter are more effective vehicles of immortality.50 In other words, precedence is given to wisdom and knowledge as carriers of value and elements establishing class distinction, to the expense of children and the women who give them life.

Alcibiades’ speech comes as a counterpoint to the previous speakers and the loftiness of their preoccupations. He isn’t concerned with the Form, he is concerned with a specific person, Socrates, and the ambiguity of his very concrete feelings for him. In line with his biography, Alcibiades wishes to undermine the society he has been dealt while at the same time finding a way to exist within it.51

Wives

This brings us to the question of women. Athenian women in the 5th and 6th century BC, particularly married ones, had property rights that were markedly inferior to those of men, facilitating their domination and oppression, as well as that of their children.52 This likely sprung from the monopoly on gestation held by women, and the resulting need to control them as the sole source of offspring. From this point of view, Athenian women, exploited for their biological and social reproductive labor, constituted a distinct economic class in the Marxian sense. This applied in particular to upper-class women, whose men owned significant property to which the women had no rights. In this way, the gap between the sexes in the upper classes was larger than in the case of, for example, peasants.53

This arrangement resulted in the oppression of women. Women had to stay at home and tend the house and were kept out of the public eye, more so in the upper classes, which had enough space to segregate their women more effectively and there was no need for the women to work outside the home.54 They produced goods, whether material, sexual, or affective, within the strict confinement of their juridical and social status, which were then necessarily appropriated by their men, since they were the only ones allowed property. Wives were only permitted to have sexual relations with their husband. They remained under his power, as did any children they produced. The duty of wives was limited to household tasks.55 Husbands were expected to keep up a certain frequency in sexual relations with their wives, but exclusivity was not essential. Only the wife had to remain faithful, because it was important to make sure paternity was certain and heirs legitimate. Marriage in general did not seem to pose questions requiring the structuring of the man’s pleasure, sexual or otherwise.56 It was primarily a question of house, household, and relations of production, particularly insofar as it concerned the woman.57

The husband’s responsibility included the exercise of a paternal role for his wife. Given that wives were often very young, their husbands, sometimes twice their age, provided them with the education necessary to tend to matters of household management as well as general conduct.58 As Foucault points out, citing Xenophon, a marriage was not primarily a relationship between a man and a woman who also happen to maintain a house and a family, but rather a structure within which the husband carried a “governmental responsibility” and the woman was expected to assimilate his teachings and perform according to expectations. The focus was not on love or pleasure, but the “reasonable practice of economy”.59

The marriage bond was characterized by asymmetry. Ischomachus, cited by Foucault, describes the start of the marriage as a matter of negotiation between the future husband and the future wife’s parents. The main criterion is the girl’s suitability as a household manager and producer of children.60 While there is emphasis on the fact that the roles of the two partners are complementary, i.e., the husband provides and sources externally while the woman preserves and manages internally, the relationship remains asymmetric because it is still the husband who appropriates the wife’s work, while the wife provides her services in exchange for livelihood and status with limited agency. The authority of the gods is called upon to legitimize this division as well as to make it binding. Any deviation or inversion of roles is announced as a danger to the “good order of the household” and thus its success.61

Ischomachus’ wife is concerned with ways to remain attractive to her husband through the years, without him reciprocating with similar preoccupations, which testifies to the unequal relationship between the two. The wife worries about being replaced with someone younger and tries to prevent it from happening by attempting to improve herself as a sexual object.62 This choice reveals her understanding of where her worth lies. Her husband, however, underlines her importance as a household manager. He promises that, as long as she does that job well, and remains active in ways specific to the home, she will remain attractive and, implicitly, not lose her privileges.63 At no point is sexual exclusivity on the part of the husband even considered, which is also why the young wife needs to understand that the locus of her worth is not her sexual attractiveness.64 In other words, that even if she were to hold sway over her husband by means of her beauty, this will not ensure her status and privilege over other women, since her true role within the couple is to ensure social reproduction. This lesson, in which her husband takes pride, is part of the young wife’s education, and serves to further structure the matrimonial relationship to the end for which it exists, that is, the economic partnership intended strictly to maintain and grow wealth as well as produce children.

When reciprocal sexual fidelity is considered, it is not because of affection, but due to the interests of the state and of lineage. Ensuring one’s children can claim that lineage by having the same mother and the same father and being the products of a lawful union preserves status and in turn maintains the stability of the state.65 It is not a sign of improvement of the status of women or an acceptance of any claim to recognition beyond the confines of their assigned roles.

Love?

Considering the organization of love in the classical period of Greece through a materialist lens helps uncover the way in which gender division was key for structuring society throughout history and served as a “pivotal element in most systems of social domination”.66 As shown above, one goal of the system described was the appropriation of women’s labor by barring women from sharing into the privileges enjoyed by men. Valuing relations with young males over relations with females was an added layer to the key objective of keeping women in an oppressed position and away from public matters, rather than merely a discerning belief in the quality of the fulfillment provided by one or the other.

This seems to indicate the existence of a dual system, constituted by male domination, or what is sometimes called patriarchy, on the one hand, and mode of reproduction as locus of exploitation, on the other. The two appear as distinct, but in fact arise from the same set of social relations, as their shared goal is to ensure the social reproduction of a specific class. In the transition to capitalism, the segregation of social life into public, productive sphere, belonging to men, and domestic, reproductive sphere, assigned to women, similarly relied on devaluing women’s bodies and work. This was crucial for consolidating wage dependency and the spread of capitalist relations.67

In her classic work on witch-hunts in medieval Europe, Silvia Federici provides a solid analysis of how difference was constructed during the transition to capitalism and how it was used to devalue the work of women in order to facilitate their exploitation. This exploitation, in turn, was one of the essential sources of surplus leading to the consolidation of capital. Faced with the crisis of feudalism, the European elite took various paths towards appropriating new types of wealth sources to extend its economic base, founding capitalism in the process.68 One of these paths, in conjunction with the privatization of land, meant appropriating the labor of women. Federici shows how the global proletariat was formed through taking control of women as reproducers of the work force, primarily by destroying their power and capacity for independent sustenance. The attack on women was launched by restructuring the rule of the patriarchy by means of waged labor and separating production from reproduction. Women became unable to support themselves, as their work was increasingly devalued. Only items produced for the market were viewed as carrying value, while reproductive work was paid at the lowest possible level, or went mostly unpaid.69

Due of the population decline of the 16th-17th century and the mercantilist belief that the larger the population the more wealth could be accrued, efforts by the state to discipline the female body and to take control of the reproductive function increased. Women who were found guilty of reproductive crimes were punished severely. This also led to the loss of knowledge and control women held collectively when it came to conception, gestation, and birth. It was during the same period that midwives were pushed out of birthing rooms and replaced by male doctors.70 As a consequence, women entirely lost control over their wombs, which became tools serving capitalist accumulation.71 Women were thus pushed out of the sphere of productive work. Motherhood was imposed on them, along with related social reproductive undertakings, and they were exploited for minimal wages as home producers.72

The creation of the housewife, fully in place by the 19th century, sealed the nature of relations between the genders and the fact that women were barred from access to a wage allowing them to survive independently, except as prostitutes.73 By excluding them from waged labor, the subordination of women to men, and their loss of control over their bodies, was completed.74

The deep divisions within the working class created and reinforced as capitalism became established, and particularly those between women and men, remain to this day the basis of capitalist accumulation and the resulting injustice and exploitation.75 Under the current capitalist order, predicated on the production of surplus and on accumulation, this same distinction is maintained in precisely the same way, by separating social life into the spheres of productive activity, the realm reserved to men and/or male authority, and household and kinship relations, generally imposed on women through various coercive and cultural instruments, including love, and requiring the appropriation of their labor to support the production of surplus.76

In that sense, what Pausanias extols and Foucault and de Ste. Croix describe in detail for classical Greece is a proto-model of what we observe in contemporary configurations. In the absence of accumulation and surplus as organizing principles, it was love and the regulation of love that successfully filled the same role in upper-class Athenian society. In other words, the system of social reproduction was secured by closely defining acceptable behavior and what was morally appropriate and what wasn’t in the practices of love. As such, privilege and societal control were inextricably connected. They formed, in fact, a unitary system.77

The essence of social reproduction has thus endured virtually unchanged into our era. Gender continues to act as a dividing line, despite sustained efforts by successive generations of activists and theorists alike towards bridging the gaps it generates. Women continue to be biological reproducers, which means their monopoly on gestation remains at the core of their oppression. They also represent the majority of social reproducers.78 Much of reproductive labor continues to be unwaged and is thus the site of particularly harsh forms of exploitation. This exploitation is still made possible by a structure of gender-based domination. As such, the exploitation of reproductive labor remains at the core of capitalist accumulation.79 The extent of this gendered exploitation varies with class and race, but nevertheless remains a constant presence in the lives of contemporary women.80 Reproductive labor, a condition of possibility for any society and still separated in a gendered domestic sphere, continues to be cast in moral terms and as a question of virtue and love.81 Love of the homoerotic kind is no longer the medium through which privilege is passed on, but has endured in its heterosexual iteration as the imperative that helps ensure women comply with being the main reproducers of the ultimate capitalist commodity, the labor force.

However, reproduction has also been a key site of feminist struggles and continued resistance to oppression. The inability to reproduce themselves socially due to exploitation at the site of production has brought women, and men, out onto the streets with a variety of demands, for example for better pay and better work conditions, for equal redistribution of wealth, or for affordable public services. They have pressured the capitalist machine of accumulation in order to put a brake on its advancement at their expense. In fact, the social reproduction of its labor force is capital’s greatest expenditure. It is, therefore, important to recognize the constancy of gender oppression predicated on social reproduction as it forces us to reconsider the history of capitalism from the point of view of social reproduction, rather than, as hitherto, only for what concerns struggles at the point of production.82

Appendix

Endnotes

- Plato, xi.

- Sheffield, 122-123.

- Plato, xiii.

- Plato, xv.

- Plato, xvi.

- Plato, xvi.

- Sheffield, 123.

- Ibid., 126.

- Foucault, 246.

- Sheffield, 122.

- Young, 102.

- Foucault, 92.

- Wright, 3.

- Ibid., 6.

- Wright, 9.

- As were most other inhabitants of Athens. However, this paper only deals with the specific interaction of propertied men and the women of the same class.

- Plato, 180d.

- Plato, 181a-c.

- Ibid., 181c.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 181d.

- Ibid., 181e.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 182c.

- Plato, 182c.

- Ibid., 183e.

- Ibid., 183e-184a.

- Ibid., 183c-e.

- Ibid., 184a.

- Plato, 184b.

- Ibid., 184c-d.

- Ibid., 178c.

- Hong, 72.

- Plato, 178e.

- Ibid., 180a-b.

- Ibid., 186b.

- Plato, 186c.

- Ibid., 187d-e.

- Ibid., 192a.

- Ibid., note to 192a, 81.

- Ibid., 195c.

- Ibid., 195b, 196b.

- Plato, 203b-204b.

- Ibid., 206b.

- Ibid., 207a.

- Ibid., 208d-209a.

- Sheffield, 128.

- Plato, 209c.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 209d, 212b.

- For an in-depth discussion of Alcibiades’ speech, see Nussbaum.

- De Ste. Croix, 100.

- Ibid., 101.

- Plato, xv.

- Foucault, 145.

- Ibid., 147.

- Foucault, 151.

- Ibid., 155.

- Ibid., 155.

- Ibid., 156.

- Ibid., 159.

- Ibid., 160.

- Foucault, 162.

- Ibid., 163.

- Ibid., 170-171.

- Young, 102.

- Mohandesi and Teitelman, 42-43.

- Federici, 99.

- Ibid., 108.

- Ibid., 144.

- Ibid., 145.

- Federici, 155.

- Ibid., 120-121.

- Ibid., 159.

- Ibid., 102.

- Young, 101.

- Ibid., 97.

- Fraser, 28.

- Ibid., 23

- Fraser, 31.

- Ibid., 23.

- Mohandesi and Teitelman, 38.

Bibliography

- Bhattacharya, Tithi. “How Not to Skip Class”. In Social Reproduction Theory, edited by Tithi Bhattacharya, 68-93. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

- De Ste. Croix, G. E. M. The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981.

- Federici, Silvia. Caliban și vrăjitoarea. București: Hecate, 2016.

- Foucault, Michel. The Use of Pleasure. The History of Sexuality. Translated by Robert Hurley. London: Penguin Books, 1987.

- Fraser, Nancy. “Crisis of Care? On the Social-Reproductive Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism”. In Social Reproduction Theory, edited by Tithi Bhattacharya, 21-36. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

- Hong, Yuri. “Collaboration and Conflict. Discourses of Maternity in Hippocratic Gynecology and Embriology”. In Mothering and Motherhood in Ancient Greece and Rome, edited by Lauren Hackworth Petersen and Patricia Salzmann-Mitchell, 71-96. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

- Mohandesi, Salar and Teitelman, Emma. “Without Reserves”. In Social Reproduction Theory, edited by Tithi Bhattacharya, 37-67. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

- Nussbaum, Martha. “The Speech of Alcibiades: A Reading of Plato’s Symposium”. Philosophy and Literature, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 1979): 131-172.

- Plato. Symposium. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Sheffield, Frisbee. “The “Symposium” and Platonic Ethics: Plato, Vlastos, and a Misguided Debate”. Phronesis, Vol. 57, No. 2 (2012): 117-141.

- Wright, Erik Olin. Understanding Class. London: Verso, 2015.

- Young, Iris M. “Socialist Feminism and the Limits of Dual Systems Theory”. In Materialist Feminism, edited by Rosemary Hennessy and Ingraham Chrys, 95-106. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Originally published by Analize: Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies 11:25 (2018, 85-101) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.