By January 1954, a Gallup poll found that only 50 percent of the American public supported McCarthy.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Editorial cartoonists, like all Americans, do not always agree with one another. Issues on which the nation was particularly divided in the twentieth century—the question of U.S. intervention prior to entering World War II, the Red Scare, the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and events in the Middle East—were particularly fertile ground for editorial cartoonists.

In the 1950s the nation feared the increase in communist-run countries after World War II. Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy’s four-year public smear campaign began in 1950 and paralleled the intimidation tactics already underway by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which had been founded in 1938 to root out subversive activities related to communism. McCarthy’s initial popularity with the American public was fed by the Cold War-fueled fear of communist influence, which led some cartoonists to agree with him. However, by January 1954, a Gallup poll found that only 50 percent of the American public supported McCarthy. The televised McCarthy-Army hearings later that year further eroded his public support. In June 1954, McCarthy was censured and by December condemned by the Senate.

As president-elect Dwight David Eisenhower prepared to steam ahead into office early in 1953, Herbert Lawrence Block, commonly known as Herblock, portrayed members of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), sliding back into the past. Herblock and other journalists feared that Eisenhower would not be able to control a right-wing Congress determined to root out communists from government. In looking out for the “little guy,” Herblock targeted politicians whose sense of power endangered fellow Americans accused of being subversives.

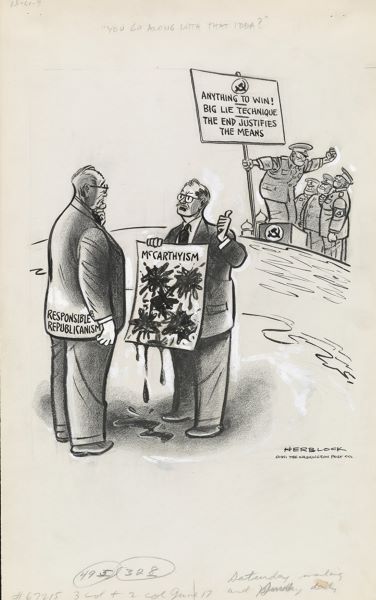

Herblock drew parallels between the tactics of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy’s mud-slinging and Soviet Union propaganda, finding each approach unacceptable. He demanded that moderate Republicans take responsibility for McCarthy’s actions. In reaction to the quest for communists in the United States, Herblock wrote, “there was real pleasure in having an outlet for my anger instead of imploding with it.”

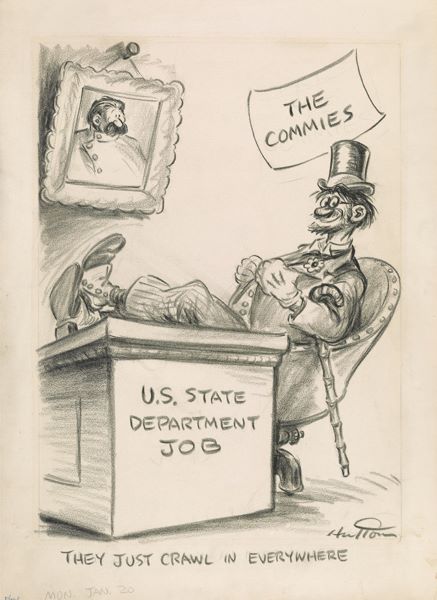

In January 1947, Carl Aldo Marzani was arrested and imprisoned for being an active member of the Communist Party while in the employ of the State Department. At the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation thoroughly investigated 314 employees, leading to dismissals and resignations. Hutton appears to believe the firings validated the methods of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Hugh McMillen Hutton spent thirty-five years as an editorial cartoonist at the Philadelphia Inquirer.

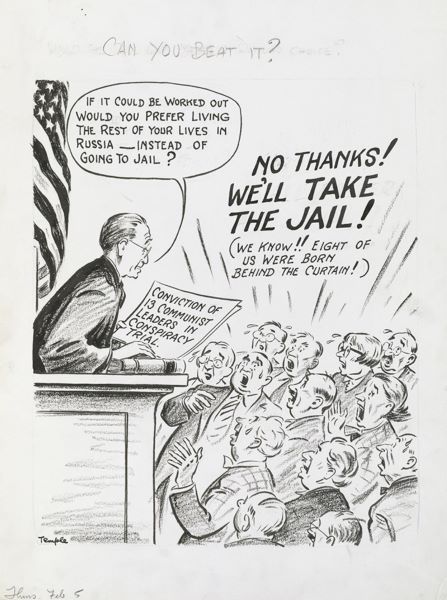

In 1953, New York Judge Edward J. Dimock offered thirteen members of the Communist Party a trip to the Soviet Union, but the convicted men and women chose, instead, to serve prison sentences varying from one to three years. As New Orleans Times-Picayune cartoonist Keith Temple makes clear, eight were born in what became Iron Curtain countries. His sarcastic jab suggests that he was disgusted, but not surprised, that Communists from Soviet Bloc countries refused to move to the Soviet Union.

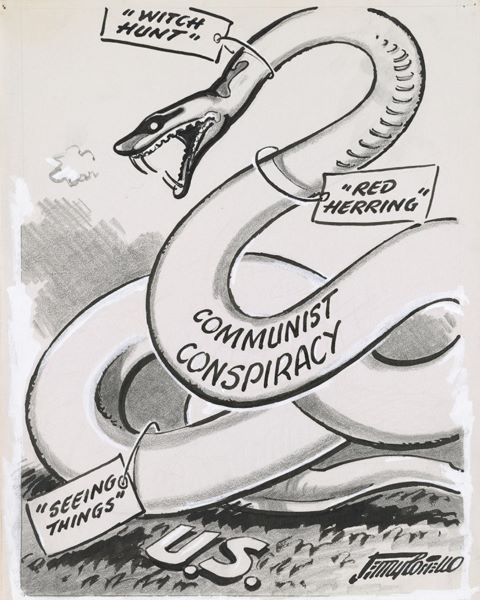

Referring to Harry Truman’s 1948 speech in which he labeled a House Un-American Activities Committee investigation a “red herring,” as well as a labor union official’s criticism of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and his fellow senators for creating a “witch hunt,” cartoonist Jerry Costello depicts communism as a vicious threat to the United States. McCarthy had just launched an investigation into the Army Signal Corps when Costello drew this cartoon. In 1954, the Army hearings became McCarthy’s undoing.

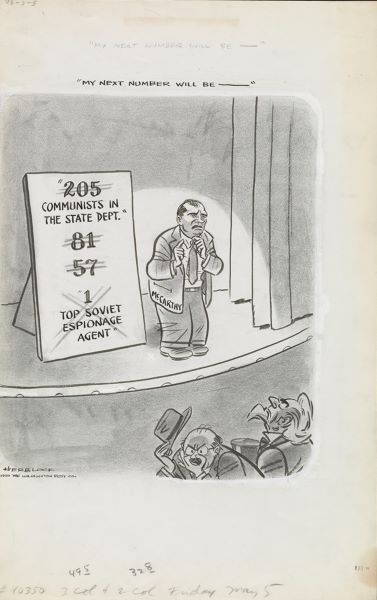

Members of the Senate were divided in their reaction to Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hearings to root out communism. Scott Lucas, a Democrat from Illinois, supported State Department employees working in fear of false allegation and challenged McCarthy, calling him a “liar.” Owen Lattimore, a State Department employee, who had been falsely accused of being a “top Soviet espionage agent,” argued that McCarthy was guilty of “Russian-type smears.” In 1950, Herblock portrayed McCarthy as a lone actor, but, by 1954 the senator’s investigative committee had ended many careers.

This Herblock cartoon depicts Joseph McCarthy as his own worst enemy. Soon after the senator claimed that he had a list of known communists working in the State Department, Herblock went on the attack, stating later, “there was real pleasure in having an outlet for my anger instead of imploding with it.” The Catholic Archdioceses of Baltimore and Washington confronted McCarthy as did Senate Democrats, but they failed to stop his investigation of the State Department and the later investigations he led. The televised Army hearings in 1954 brought about McCarthy’s downfall.

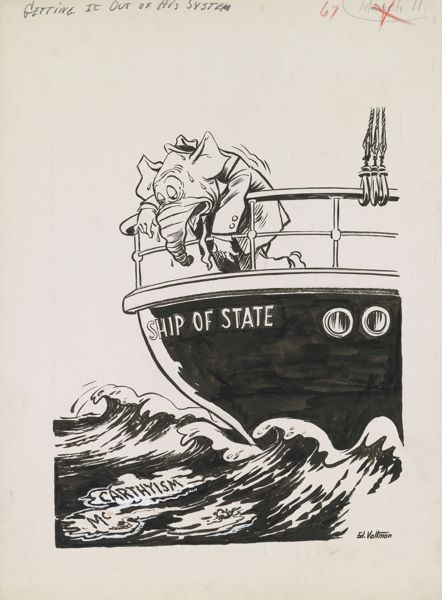

In 1954, as the Army-McCarthy hearings exposed the Wisconsin senator’s bullying tactics on national television, Joseph McCarthy’s reputation plummeted. Estonian émigré, Edmund Valtman, who had lived through German fascism and Soviet communism, believed the Republican Party needed to purge the red scare obsession from its agenda. Already an established cartoonist, Valtman emigrated to the United States in 1949 and worked for the Hartford Times between 1951 and his retirement in 1975.

As Joseph McCarthy continued to conduct hearings intent on exposing communists, Republicans began to distance themselves. The issue came to a head when President Eisenhower nominated Charles E. Bolen to serve as ambassador to the Soviet Union. Bolen, who was expressly in favor of accommodating rather than containing the Soviet Union, found Republican support during McCarthy’s investigation. Leo Roche, who cartooned for the Buffalo Courier-Express for at least twenty years, shows the Democrats relishing the Republican Party dilemma.

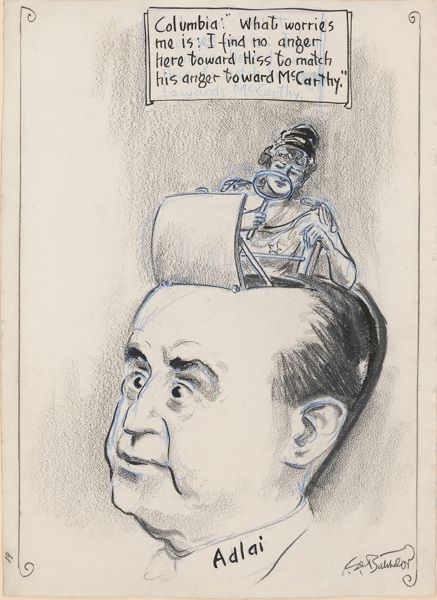

During the 1952 presidential election, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy repeatedly accused Democratic Party candidate Adlai Stevenson of collusion with Soviet communists. Stevenson had given a deposition in favor of Alger Hiss during his Soviet espionage trial in 1948, so McCarthy and others used this as evidence of communist sympathies. Clarence Batchelor drew for the New York Daily News for thirty-eight years. He and his paper grew increasingly disenchanted with liberalism and by 1952 sympathized with McCarthy’s rhetoric.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, 03.21.2015, to the public domain.