Democracy’s meaning and significance altered in a relatively gradual and piecemeal fashion.

By Dr. Christopher Hobson

Visiting Research Fellow

United Nations University

Introduction

Democracy is like a rising tide; it only recoils to come back with greater force, and soon one sees that for all its fluctuation it is always gaining ground. The immediate future of European society is completely democratic: this can in no way be doubted.

Alexis de Tocqueville (1833) (Tocqueville 1958: 67)

What is Democracy; this huge inevitable Product of the Destinies, which is everywhere the portion of our Europe in these latter days? There lies the question for us. Whence comes it, this universal big black Democracy; whither tends it; what is the meaning of it?

Thomas Carlyle (1850: 13)

Following Napoleon’s last hurrah at Waterloo in June 1815, Europe’s great monarchies were still standing (some only just), but they now existed in a world that had undergone irreversible change. The ideas and principles of the revolution remained, even if their French standard-bearers had finally been defeated. This meant a simple restoration of the ancien régime was not possible. With historic right and custom undermined, international society would instead be explicitly founded on principles of legitimacy that were defined against the popular doctrines that had emerged from revolutionary France.

If many of the fundamental tenets of the revolution would eventually, in one form or another, succeed the old hierarchical order of the monarchy, aristocracy and church, in the immediate aftermath of French defeat, the forces of reaction were overwhelmingly in the ascent. The course of the revolution seemingly vindicated many of the complaints against popular rule levelled throughout the centuries, with the excesses of the Terror providing clear evidence of the dangers of seeking to establish a democracy in the modern world. John Jay, one of the authors of the Federalist papers, summed up the prevailing sentiment in a letter to William Wilberforce: ‘The French revolution has so discredited democracy . . . that I doubt its giving you much more trouble’ (quoted in Morantz 1971: 149). In the short term, this was a rather accurate assessment, although the situation slowly changed, spurred by developments in the United States and the 1848 revolutions. Given that democracy’s meaning and significance altered during this period in a relatively gradual and piecemeal fashion, the structure and analysis of this article focuses more on these longer trends. It corresponds to Reinhart Koselleck’s observation that often conceptual change is ‘slower and more gradual than the pace of political events’ (Koselleck 1996: 66).

Democracy Reviled

With the French finally defeated, popular sovereignty was identified as the ultimate cause of the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. The fleeting ascendance of the Jacobins, and subsequent rise of Napoleon, seemed to correspond closely to the warnings found in classical and contemporary works about the unstable and violent nature of popular states. Polybius’s understanding of the cyclical nature of constitutions, whereby democracy deteriorated into anarchy, only to be rescued by a powerful leader, resonated especially strongly (Polybius 1927: book 6). While there were a number of attempts at ideological innovation from Thomas Paine, William Godwin and other radicals who sought to release democracy from the heavy legacy of Athens, the ancients still remained the dominant referent (Canfora 2006: 47; Costopoulos and Rosanvallon 1995: 148). The violence of the Terror would further stain the image of democracy. As Giuseppe Mazzini later lamented, people ‘no sooner hear the name of democracy than the phantom of ’93 rises immediately before them. With them democracy is a guillotine surmounted by a red cap’ (Mazzini 2001: 4; original emphasis). For much of the nineteenth century democracy would be ‘almost unanimously’ linked to Jacobinism (Naess et al. 1956: 113), blamed (somewhat unfairly) for the revolutionary wars, and portrayed as a great menace to stability and peace. Negative interpretations of democracy were by no means the exclusive preserve of reactionary forces in Europe; they could also be found in the United States. ‘Look at France!’ Noah Webster concluded. ‘There you have a picture of real democracy’ (quoted in Morantz 1971: 149). John Adams surmised: ‘Robespierre is a perfect exemplification of the character of the first bellwether in a democracy’ (quoted in Bailyn 1967: 282), further warning that democracy ‘when by chance it happens to get the upper hand for a short time, it will be revengefull bloody and cruel’ (quoted in Levin 1992: 84). Much like the ‘red menace’ during the Cold War, democracy came to be identified as a constant, underlying threat both to the fledging republic of the United States and to the European states that had narrowly survived the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

The prevailing opinion during the restoration was that the result of applying the ancient form of democracy to the modern world had been the chaos, violence and tumult of the revolution. Ideological apologists drew a straight line between ancient Greece and revolutionary France, reiterating classical tropes about democracy degenerating into tyranny and despotism. Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre were two prominent apologists who sought to counter the popular doctrines that had emerged. Reflecting on the French experience, Bonald concluded: ‘Despotism and democracy are, fundamentally, the same government’ (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 35). In his view, the evils of democracy were almost limitless. The levelling that democracy required was brought about through violence and revolution; it promoted, if not demanded, atheism; and it also spelled the end of reason, judgement and literature (Christophersen 1966: 37). Painted in this light, democracy was nothing less than a threat to the whole of European civilisation. Maistre reiterated similar themes: democracy as violent, unstable and ‘government of the mob’ (Maistre 1996: 155). In addition to these standard criticisms, he explicitly sought to refute Jean- Jacques Rousseau’s Social Contract, which was widely blamed with providing the revolution’s theoretical blueprint. Recalling Rousseau’s judgement, Maistre pointedly said: ‘It remains to be seen how a government that is made only for gods, is nevertheless proposed to men as the only legitimate form of government’ (Maistre 1996: 152; original emphasis). Democracy was deployed as a counter- concept to monarchy, with the destructive characteristics of the former imbuing the latter with positive meaning:

One can say in general that all men are born for monarchy. This is the oldest and the most universal form of government . . . Democracy above all is so rare and so transient, that we are allowed not to take it into account.

Maistre 1996: 119

Monarchy recognised distinctions, protected religion and was best able to promote happiness, stability and civilisation. The interventions of Bonald and Maistre offer strong examples of the way apologists sought to counter popular doctrines by challenging and denying the conceptual innovations of the revolution.

Democracy’s potential for despotism was noted not only by defenders of the ancien régime, but also by early liberal thinkers. A particularly relevant case is Immanuel Kant, who held a strongly classical understanding of democracy. Like James Madison and Abbé Sieyès, Kant dismissed democracy because he viewed it through an Athenian lens: it was ‘necessarily a despotism’ (original emphasis), as it was a direct form of rule where executive and legislative powers were not separated. In comparison, a republic was based on representation. Kant explained:

If the mode of Government is to conform to the idea of Right, it must embody the representative system. For in this system alone is a really republican mode of Government possible; and without it, let the Constitution be what it may, it will be despotic and violent.

Kant 1970: 99–102

Democracy remained in low esteem across most of the political spectrum, with only a few radicals explicitly identifying themselves and their cause with it. During the conservative reaction there was a tendency not to distinguish between the two forms of popular sovereignty that had emerged from the revolution: democracy was equated completely with the ré-totale of the Jacobins. The mediated version of popular sovereignty, the ré-publique, was obscured from view, and most liberal thinkers that did espouse it generally saw it as distinct from democratic rule. Even this more moderate form of popular sovereignty remained a threat to monarchical powers, which sought to rebuild an order based on hereditary rights and social hierarchy. In this regard, popular sovereignty and democracy may have been widely discredited, but they could not be ignored when the peacemakers met at Vienna.

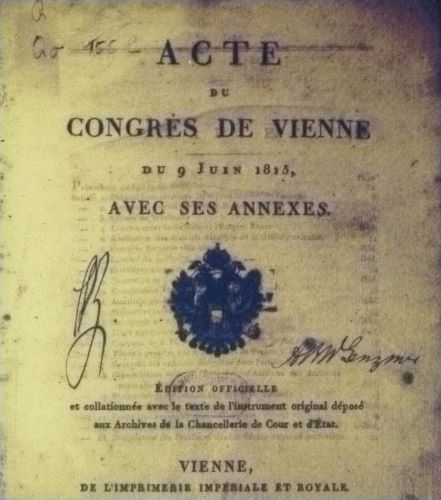

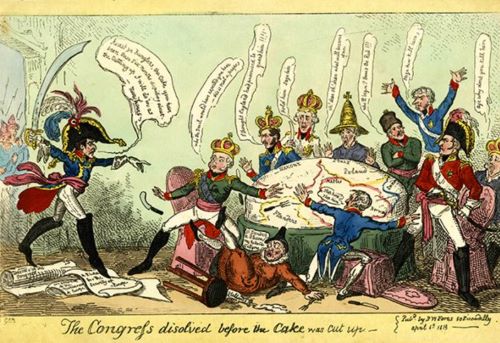

The Congress of Vienna: Building a Legitimate Order

After France’s defeat the forces of reaction may have been in the ascent, but the key powerbrokers were acutely aware of their precarious position. As a result, a remarkably lenient peace was initially imposed, shaped by a fear that too harsh a settlement would cause the revival of Jacobinism, something which could spell the end of the ancien régime once and for all. This awareness was reflected by the Duke of Wellington: ‘Revolutionary France is more likely to distress the world than France, however strong in her frontier, under a regular government; and this is the situation in which we ought to endeavour to place her’ (quoted in Osiander 1994: 202). The challenge for the victorious great powers was putting Europe back together in a way that would secure their own interests while preventing the reappearance of a revolutionary France.

Peace with France had already been concluded in the first Treaty of Paris in May 1814, leaving the Congress of Vienna for dealing with more general questions about the nature and makeup of international society. The significance of this meeting was not lost on the participants, with Prince Metternich noting that ‘it does not require any great political insight to see that this Congress could not model itself on

any predecessor’ (quoted in Langhorne 1986: 318). This was the first attempt to consciously construct and regulate relations between states, establishing a clear set of principles defining rightful membership of and behaviour in international society (Clark 2005; Ikenberry 2001; Langhorne 1986). As Martin Wight explains, previously ‘the society of states needed neither definition nor explanation. It was what it was, and everybody knew its members’ (Wight 1972: 5). The ancien régime had been legitimated by its spontaneity, through what it was, rather than what it said.1 Rule was based on historical right: custom and precedent were the foundations of international society and its members. It is for this reason that Wight talks about the existence of a dynastic international order, without there being an explicit principle of dynastic sovereignty (Wight 1977: 153–4). Indeed, it was not a coincidence that Edmund Burke was one of the first to clearly espouse principles of conservatism, as these were somewhat of an anathema to its worldview. Having been attacked with doctrine, conservatives were now forced to answer on these terms.

The statesmen at Vienna were forced to incorporate principles of legitimacy as a way of managing the unchangeable realities brought about by the revolution. The prominent role legitimacy played in the settlement was largely due to the tireless campaigning of the French representative, Prince Talleyrand, who was most attuned to, and insistent on, the need for principles or legitimacy (he used these two terms interchangeably) as a central dimension of the new order being constructed. One need only casually glance through his correspondence during the Congress to observe how important legitimacy was to his thought and rhetoric (Pallain 1881). Talleyrand immodestly, though somewhat accurately, regarded this as his great contribution. On arriving in Vienna, he announced: ‘I ask for nothing but I bring you something important – the sacred principle of legitimacy’ (quoted in Nicolson 1946: 143). In promoting this ‘sacred principle’ Talleyrand was obviously not acting out of altruism. Given France’s weak negotiating position, framing the discourse in terms of principles was a valuable bargaining tool against the other great powers (Nicolson 1946: 157). Even if the constant talk of legitimacy was self- serving, to be successful Talleyrand, like any innovating ideologist, had to tailor his arguments for acceptance by other parties, which influenced how he presented his case.

Monarchy was identified as the form of rule most capable of providing order at both the domestic and international levels. Along these lines, Talleyrand argued that the Bourbon monarchy should be maintained for practical reasons, presenting it as the only real possibility for stability within France. Talleyrand persuasively made his case to Tsar Alexander: ‘In order to establish something lasting which will be accepted without protest, one must have a principle on which to act. . . . As for a principle, there is only one – Louis XVIII is a principle’ (Ferrero 1941: 89). What made Louis XVIII the best chance at ‘establishing something lasting’ was the historical role the Bourbons played in the constitution of the French state. The great threat was revolution, which Talleyrand believed could be best avoided through legitimate government. Legitimacy did not emerge specifically from monarchy; rather, it developed over time and was supported indirectly by the consent of those ruled. Talleyrand explained:

Authority, to be legitimate, must have existed for a long succession of years; and, accordingly, we see that legitimate power . . . is the form of government least likely to expose the people to the perilous chances of revolution, and is, therefore, the form to which they are bound in their best interests to submit.

Pallain 1881: 241

In this sense, Talleyrand followed Burke in regarding rule as being legitimated not by principles but by custom. In the European context this clearly gravitated towards monarchy.

Monarchy may have been central to the international order founded at Vienna, but it could no longer be solely justified through history and precedent, as these had been undermined first by the revolution and then by ‘the grand usurpation’ of Napoleon (Metternich 1880: 278). Writing to his king at the conclusion of the Congress, Talleyrand described the changed situation with great clarity when reflecting on ‘what is legitimacy, whence it proceeds, and in what it consists’:

In the time when religious feelings were all- powerful and deeply engraved in hearts and minds of men, it was possible to believe that the sovereign power was an emanation from the Divinity. . . . But in these days, in which there remains scarcely a trace of these feelings . . . men will no longer allow the claim of legitimacy to this origin. In the present time the general opinion, one that it would be vain to attempt to weaken, is that Governments exist only for the sake of the people; a necessary corollary to this opinion is that legitimate power is the form of government best calculated to secure the prosperity and tranquillity of the people.

Pallain 1881: 240–1

Shorn of divine blessing and historical right, monarchy would have to be legitimated in a much more direct manner than in the past.

While Talleyrand may have been more attuned to the need to adjust to these changed circumstances, Metternich was much more aware of the limits of compromise possible with the revolution’s principles. He determined that the only way of protecting society against revolution was, quite simply, ‘by allowing no innovations’ (quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 62). As Carsten Holbraad explains, Metternich ‘wanted to maintain all established governments and existing institutions because he believed that a defeat of authority in any state could lead to a collapse of order throughout the society of Europe’ (Holbraad 1970: 33). Monarchy embodied and preserved the old social order; the destructive principles of the French Revolution continued to threaten it. Like other apologists, Metternich employed democracy as a counter- concept to monarchy:

It is true that I do not like democracies. Democracy is in every case a principle of dissolution, of decomposition. It tends to separate men, it loosens society. I am opposed to this because I am by nature and by habit constructive. That is why monarchy is the only government that suits my way of thinking.

Quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 39

A prototypical apologist of the existing order, Metternich remained resolutely opposed to the revolutionary doctrine of popular sovereignty:

The sovereignty of the people can only be a fictitious idea because, since the meaning of sovereignty is unquestionably that of supreme power, and since that power is incapable of being exercised by the people, it must be delegated by them to an authority other than the sovereign.

Quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 41; original emphasis

While innovators in the United States and France had tried to deal with this problem through the representative system, Metternich was sceptical, regarding it as a dangerous compromise: ‘It binds the hands of those in power without untying those of the people’ (quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 43). Despite his influence and his concerted efforts at refuting and suppressing popular doctrines, Metternich’s alternative of vainly denying change could never be workable in the long run.

The international order constructed at Vienna was fashioned on what had come before, but was unavoidably built with tools inherited from the revolutionaries. To re-establish the ancien régime, precedent ‘had to be replaced by principle, or, failing that, violence’ (Osiander 1994: 186). This gave rise to what Henry Kissinger describes as ‘the conservative’s dilemma’:

The conservative, when he organizes himself politically, becomes, in spite of himself, the symbol of a revolutionary period. His fundamental position involves a denial of the validity of the questions regarding the nature of authority; but the questions, by exacting a reply, have demonstrated a kind of validity.

Kissinger 1973: 193

With custom and precedent destroyed, conservatives were forced to answer the revolutionary question of rightful authority, and to legitimate the order they were constructing by recourse to abstract principles. There was, however, a certain futility in trying to maintain and reinforce the position of monarchy through legitimacy. Once framed in these terms a crucial concession had been made. Carl Schmitt makes this point strongly: ‘What was still historically vibrant in the monarchy’s principle of form did not lie in legitimacy. . . . A monarchy that is nothing other than “legitimate” is already politically and historically dead’ (Schmitt 2008: 245).

In establishing principles of legitimacy that promoted and protected monarchy, a more immediate outcome of the Vienna settlement was the creation of an international society more homogeneous than that which had preceded it. As Andreas Osiander observes, ‘by 1815 the variegated pattern of pre- revolutionary constitutional forms had given way to a considerably more standardized international landscape, which was shaped to a much greater extent than before by abstract theorizing’ (Osiander 1994: 233). This transition arose in part from a new- found awareness of how the domestic and the international spheres were intertwined, with principles of legitimacy in the two realms being deeply connected. Revolutionary France had powerfully demonstrated that changes to the constitution of one state could have drastic consequences for others. At Vienna, a new relationship between international society and its members was established, one that regarded a state’s domestic makeup as something of concern for all. In this regard, Talleyrand argued that legitimacy ‘can alone secure internal tranquillity in individual states, and at the same time protect them from being subject in their mutual relations to the influence of force only’ (Pallain 1881: 222). Heterogeneity in Europe, especially among the great powers, had come to be identified as a threat. The loss of spontaneity and the weakening of customary rights reinforced the need for a greater degree of homogeneity, as the ancien régime was much more susceptible to challenge. It was this belief in the intertwined fate of states that drove Metternich’s insistence that change must be prevented anywhere. Europe may have been a society of sovereign states, but the fates of its members were closely connected, which necessitated a level of conformity around the monarchical principle.

Embedding domestic legitimacy so directly within international society in turn opened space for the corollary of intervention (Clark 2005: 94). On this point, however, the British would diverge from the eastern powers. In short, the former was concerned about revolution in France, whereas the latter were concerned about revolution anywhere. This manifested itself in the creation of the Holy Alliance between Austria, Prussia and Russia, which became the mechanism through which the conservative powers sought to suppress popular uprisings and uphold the monarchical principle. These differences would become more pronounced at the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, the first meeting of its kind since Vienna. The emerging interventionary doctrine of the Holy Alliance was guided by Metternich, who regarded Europe as a whole body, and revolution as a dangerous disease that would easily spread (Holbraad 1970: 21, 29). In contrast, Britain’s Lord Castlereagh doubted that revolution in one country was necessarily contagious, and was also acutely aware that British public opinion would not countenance a general reactionary alliance (Bobbitt 2002: 166).

These respective positions became clearer at Troppau in 1820 and Laibach in 1821, where the great powers sought to deal with unrest in Spain and Italy. The British argued against intervention, stating that the Quadruple Alliance had been meant to stop France from reappearing as a threat, not to prevent revolution in general. It was not, in Castlereagh’s words, ‘an union for the government of the world or for the superintendence of the internal affairs of other States’ (Breunig 1977: 139). For the eastern powers, however, any internal changes were regarded as necessarily a challenge to an international order composed of states legitimated through custom and historical right. Russia proposed a protocol that asserted a general right to intervene ‘to prevent the progress of the evil with which the body social is menaced, and to devise remedies where its ravages have begun or are anticipated’ (quoted in Bobbitt 2002: 167). Castlereagh countered:

It is impossible not to consider the right which the Monarchs claim to judge and to condemn the actions of other States as a precedent dangerous to the liberties of the world . . . No man can see without a certain fear the lot of every nation submitted to the decisions and to the will of such a tribunal.

Quoted in Bobbitt 2002: 167

The Russian suggestion was initially withdrawn after this protest, but in the subsequent Troppau Protocol the members of the Holy Alliance restated an ‘undeniable right’ to intervene where revolution occurred (Hertslet 1875), which Castlereagh contested in a strongly worded circular. The split between Britain and the eastern powers was confirmed at the Congress of Verona in 1822, where the former clearly advocated a doctrine of non- intervention: ‘Our engagements have reference wholly to the state of territorial possession settled at the peace; to the state of affairs between nation and nation; not . . . to the affairs of any nation within itself’ (quoted in Holbraad 1970: 122–3). The incompatibility between the liberal aspects of Great Britain’s constitution and the staunchly conservative nature of the eastern powers had been successfully papered over during the wars and at Vienna due to the common French threat, as well as the unique bridging role played by Castlereagh. With these two factors now gone, the powers diverged.

Multiple challenges to the conservative project soon appeared, reflecting the great difficulty of trying to supress the popular principles that had emerged from the American and French revolutions. With the Monroe doctrine, the youthful United States sought to protect its interests and the newly born Latin American republics from European interference. Meanwhile in Europe, Greece and Belgium both gained their independence, representing notable victories for popular sovereignty. Of more importance was the 1830 revolution in France, which signalled the end of Bourbon rule and further weakened the conservative attempt to re- establish the historical foundations of the monarchical order. Even if the revolution did not result in a dangerous France, the damage was done in the French crown now being granted by the people (Albrecht-Carrié 1958: 32; Schroeder 1994: 667). Metternich was particularly dismissive of a monarchy resting on the consent of the people, describing it as ‘a monster lacking vitality, an abstraction which no amount of work by its authors and partisans will ever furnish with substance’ (quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 293). With Louis- Philippe not the King of France, but the King of the French, the doctrine of popular sovereignty became the foundation for another great power.

Despite these important developments, the conservative cause was far from lost. The Holy Alliance proved, for the most part, successful at maintaining the conservative domestic arrangements that had been reinstituted at Vienna through to 1848. This was a major achievement, given the significant socio- economic changes underway, as well as growing liberal and nationalist pressures. The Holy Alliance was not only worried about Europe, however. Metternich was also troubled by what was taking place in the Americas, noting that the European sovereigns had to maintain there, ‘as far as possible, the monarchical principle against the advance of universal democracy’ (quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 255–6). He was right to be concerned.

The Transformation of Democracy in the United States

While reaction was in full force across Europe, democracy was making notable progress on the other side of the Atlantic. Following on the heels of the dramatic upheavals in the United States and France, revolutions in Latin America resulted in the establishment of a series of independent republics based on popular sovereignty. Further north, in the United States changes continued apace as the country expanded across the continent. The gulf separating the United States, established on popular sovereignty, from the conservative sentiment prevailing in Europe was observed by Jeremy Bentham, one of the few radical enough to talk of democracy positively in the immediate aftermath of the French revolution. In the 1817 pamphlet ‘Plan of Parliamentary Reform’ Bentham asked rhetorically: ‘By this bugbear word democracy, are the people of this country to be frightened out of their senses?’ (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 94). In a clear case of conceptual contestation, he directly tried to counter the efforts made by states-men at Vienna to demonise democracy when seeking to establish the monarchic principle: ‘In the language of legitimacy and tyranny, and of the venal slavery that crawls under them, democracy and anarchy are synonymous terms’ (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 95). Bentham chastised this attempt to ‘strike terror into weak minds’, arguing that the falsity of the position was demonstrated by the United States, which was the true embodiment of democracy’s meaning. ‘Two words – Democracy and Anarchy – produced the disease: one other word – America – may take the lead in the cure,’ he boldly proclaimed (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 95, 98).

The shift towards a positive understanding of democracy in the United States began in the opening decades of the nineteenth century and was largely complete by the 1840s. The magnitude and speed of this development was not lost on contemporaries. Samuel Goodrich observed that ‘the word democracy . . . has essentially changed its signification’. The transformation was so great that

we who are now familiar with democracy, can hardly comprehend the odium attached to it. . . . [People] not only regarded it as hostile to good government, but associated it with infidelity in religion, radicalism in government, and licentiousness in society. It was considered a sort of monster.

Quoted in Morantz 1971: 11

The North American Review reached a similar judgement in response to an address by the attorney general in which he described the United States as a ‘representative democracy’:

No man knows better than he [the attorney general], what would have been the horror of the framers of the Constitution, could they have been told, that in fifty years time, the government they were setting up with such carefully framed safeguards against what they called democracy would be itself called a democracy by one of its own highest officers.

Quoted in Morantz 1971: 12–13

This conceptual transformation is even more remarkable given that it occurred without a corresponding change in the formal political institutions of the United States.

The founding fathers described what they established as a republic, which entailed a representative government supported by checks and balances and based on popular sovereignty. In the opening decades of the nineteenth century democracy would slowly shed its Athenian baggage, and increasingly became associated with this representative system. Republicanism – pessimistic about human nature, constantly stressing the need for virtue and somewhat backward looking – was increasingly ill suited to the realities of nineteenth-century America. In contrast, democracy ‘was a vision for the future. Progress- orientated, it conveyed a buoyant optimism about human nature and the endless possibilities open to the American nation’ (Morantz 1971: 230). Both republicanism and democracy were underpinned by a conception of popular sovereignty, but whereas the former emphasised restraints on the people, the latter suggested a greater faith in them. Democracy thus came to be associated with a fuller degree of popular power and egalitarianism than republicanism. The growing acceptance of democracy in the United States can be seen in this statement by Elias Smith, an early exemplar of the shift taking place:

The government adopted here is a DEMOCRACY. It is well for us to understand this word, so much ridiculed by the international enemies of our beloved country. The word DEMOCRACY is formed of two Greek words, one signifies the people, and the other the government which is in the people . . . My Friends, let us never be ashamed of DEMOCRACY!

Quoted in Dupuis- Deri 2002: 242–3

In similar fashion, in 1816 Thomas Jefferson would declare that ‘we in America are self- consciously . . . democrats’ (quoted in Dupuis- Deri 2002: 243). The United States was starting to adopt democracy as a label.

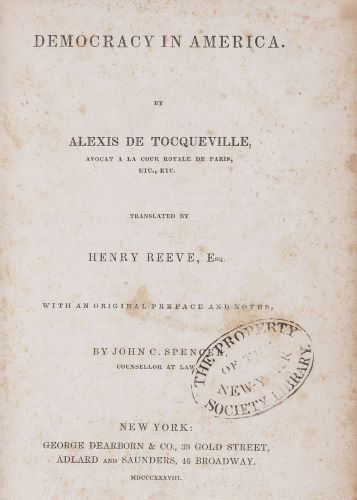

The increasingly positive connotations of democracy, and its suggestions of greater popular power, emerged from political battles taking place during the establishment of the American party system. The presidential election of 1828 was a notable moment in this shift, in which Andrew Jackson won by presenting himself as a ‘plain democrat’, using the term to appeal to ordinary voters through its strong egalitarian con-notations. It was in the context of Jacksonian democracy, as a new form of mass politics was emerging, that Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont made their fateful journey to the United States. The result was Tocqueville’s monumental Democracy in America, the first part published in 1835, and the second following in 1840. His highly influential work would strengthen the association between the United States and democracy in the European and American psyches. Tocqueville may not have been as conscious of his role as an innovating ideologist as some other actors considered thus far, but his work had similar consequences in terms of shaping the way people understood democracy.

Tocqueville’s purpose for studying the United States was to better understand democracy and how it would develop in the future. In Europe the conflict between popular sovereignty and monarchy meant that it was difficult to ascertain the ‘true character’ of democracy, but in America ‘democracy follows its own inclinations’ (Tocqueville 2003: 228). The United States could provide insight on this emergent form: ‘I have looked there for an image of the essence of democracy, its inclinations, its personality, its passions; my wish has been to know it if only to realize at least what we have to fear or hope from it’ (Tocqueville 2003: 24). Given his stated aims, and that his account was widely read and interpreted as definitive, it is of great significance how Tocqueville understood democracy. While Tocqueville’s use of the concept remains somewhat confused, being employed in multiple ways across the two volumes, democracy is primarily understood in sociological terms. Tocqueville observed that, devoid of the hierarchical social structure that defined European polities, ‘the social condition of the Americans is eminently democratic’ (Tocqueville 2003: 59). This led him to suggest that democracy – understood to entail a degree of social equality – was inevitable in Europe. He explained:

The gradual unfurling of equality in social conditions is, therefore, a providential fact which reflects its principal characteristics; it is universal, it is lasting and it constantly eludes human interference . . . Any desire to halt democracy would then appear a struggle against God himself.

Tocqueville 2003: 15

Developments towards greater egalitarianism in society would, in turn, place pressure for more equality in the political sphere (Tocqueville 2003: 66). The implication was clear: political democracy was, to a certain extent, an unavoidable consequence of the levelling impulses of democracy in the social realm.

In prophesying the ‘irresistible revolution’ towards democracy (Tocqueville 2003: 15), Tocqueville was not necessarily offering norma-tive support for this shift. His thought was marked by a deep sense of ambivalence towards democracy. Tocqueville was first and foremost a liberal. He made this point emphatically in a parliamentary speech in 1841: ‘I passionately love liberty, the rule of law, and respect for rights, but not democracy’ (quoted in Canfora 2006: 18–19). His great fear was that democracy would give rise to the ‘tyranny of the majority’, which would destroy the civil and political rights he valued so highly. This led to a distinctive interpretation of America: ‘My main complaint against a democratic government as organized in the United States is not its weakness, as many Europeans claim, but rather its irresistible strength’ (Tocqueville 2003: 294, 776). Tocqueville’s voice was to prove particularly influential in how the American experiment was received. At one end of the political spectrum, John Stuart Mill’s thinking was clearly shaped by the idea of the ‘tyranny of the majority’ (John Stuart Mill 1991: chs 6–7), at the other, when reflecting on democracy Metternich would observe that ‘I have always been of de Tocqueville’s opinion’ (Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 39).

Similar concerns to Tocqueville’s were voiced by James Fenimore Cooper in The American Democrat, published in 1838. Cooper saw the tyranny of the majority manifesting itself most fully through the overriding force of public opinion: ‘No tyranny of one, nor any tyranny of the few, is worse than this’ (Cooper 1838: 71). Echoing the fears previously voiced by conservatives such as Burke and Maistre, Cooper sug-gested that what made this form of tyranny so terrible was its totality:

In a monarchy, adulation is paid to the prince; in a democracy to the people, or the publick. Neither hears the truth . . . and both suffer for the want of the corrective. The man who resists the tyranny of a monarch, is often sustained by the voices of those around him; but he who opposes the innovations of the publick in a democracy, not only finds himself struggling with power, but with his own neighbors.

Cooper 1838: 147

Cooper and Tocqueville shared with fellow liberals Constant and Kant a fear that democracy was liable to fall into despotism, but the source of their concern differed. For the former, the problem was sociological: the levelling nature of democracy was the root cause. For the latter, it was institutional: as they still understood democracy as a direct form of rule, the potential for tyranny stemmed from a lack of representation and insufficient constitutional safeguards. But what united these thinkers was a grave concern that the advent of democracy threatened hard-won individual liberties. As can be seen, it was not only conservatives and reactionaries that feared the emergence of democracy. Liberals remained wary, instead emphasising constitutionalism and representation, which were still generally regarded as distinct from democracy.

Emerging Arguments for Democracy

Despite residual concerns held by both conservatives and liberals, the shift in American discourse whereby democracy became a valued and positive concept was effectively complete by the middle of the nineteenth century. As Calvin Colton judged in 1844, ‘we are a Democracy and Democrats. These are national designations, not party titles’ (Colton 1844: 9). This was identified as a sign of things to come:

Democracy will prevail. And it will prevail under that name. It is too late in the age of the world, in history, and in the progress of human society, to give another name to this thing. That is the common symbol destined to be employed, throughout the world, to denote popular forms of government.

Colton 1844: 10–11; original emphasis

The United States, as Tocqueville eloquently announced, was at the vanguard of experiments with popular sovereignty and democratic rule. The American experience was seen as a harbinger of Europe’s future, where the futility of rebuilding a monarchical order based on custom and freedom was becoming increasingly evident.

As the nineteenth century progressed, a number of different arguments accounting for the perceived rise of democracy can be identified. They are interrelated and overlapping but can be distinguished into four main types: (1) sociological, (2) natural rights based, (3) utilitarian and (4) nationalist. The more central a concept is to political discourse, the greater is the likelihood that there will be multiple, ambiguous and even conflicting meanings coexisting. This is what started to happen to democracy during this period. In this regard, Luciano Canfora suggests that between 1815 and 1848 democracy ‘covered many ways of thinking, from progressive liberalism (or ex-Jacobinism or crypto-Jacobinism) to socialism in its newer and more remote incarnations’ (Canfora 2006: 69). In contrast to W. B. Gallie’s widely cited claim that democracy is ‘essentially’ contested, it can be seen that it was only during the nineteenth century that contestation became a significant feature of democracy, as its normative value and political utility increased. It was not until the French Revolution that democracy began to re- emerge as a fighting word.

The sociological argument offered a broader and more expansive notion of democracy in which it represented a more equal kind of society, rather than a specific form of state or government. Tocqueville, as was seen above, provided the most influential account of this understanding: ‘democracy constitutes the social state’ (quoted in Costopoulos and Rosanvallon 1995: 150). He viewed the movement towards social equality as inevitable, and these changes would in turn lead to demands for greater equality in the political sphere. From this perspective, reactionary policies aimed at suppressing democracy were futile and ultimately self- defeating. The best strategy was to recognise this transformation taking place and seek to control it, or at least adjust to it. The power of the people was the future, and it was through rec-ognising and responding to this that it might be possible to avoid the tyranny of the majority, and transition to a form of popular rule that protected liberal rights.

Natural- rights arguments for popular rule had a long lineage, with John Locke’s early intervention being particularly determinative. In the late eighteenth century this line of thinking could be found in the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The argument remained simple and powerful: all individuals have basic, inalienable rights based on their humanity. Individuals contract together to secure and protect these rights, with the state and government they constitute ultimately being based on the consent of these individuals. The people are thus sovereign. In Rights of Man, Thomas Paine stated this clearly: ‘Governments must have arisen, either out of the people or over the people’ (Paine 1988: 220; original emphasis). In Paine’s words, government was ‘a necessary evil’, required for protecting the basic rights of the individual. And if the state did not do so, the people retained a residual right to revolution. While social-contract theory did entail popular sovereignty, it did not necessarily have to result in democratic government. As noted, many liberals remained sceptical of democracy’s ability to properly protect individual rights, also worrying that its levelling instincts were a threat to property. Over time, however, the positive evaluations of more radical liberals, such as Paine, William Godwin and Richard Price, became more accepted. Godwin argued that democracy offered the possibility for individuals to better realise their innate potential:

Democracy restores to man a consciousness of his value, teaches him by the removal of authority and oppression to listen only to the dictates of reason, gives him confidence to treat all other men as his fellow beings, and induces him to regard them no longer as enemies against whom to be upon his guard, but as brethren whom it becomes him to assist.

Godwin 1793: ch. 14

For liberals to have confidence that this could occur it was necessary that popular rule should be tempered and restrained so that these natural rights were protected and ensured. In this regard, in the version of liberal democracy that developed it was the liberal element that was clearly dominant (C. Hobson 2009).

Utilitarian thinkers were sceptical of natural- rights arguments, famously dismissed by Bentham as ‘nonsense upon stilts’. Yet they found other reasons to support democracy. James Mill identified the representative system as the best method of government, but still conceived of democracy as a direct form of rule (James Mill 1820). As noted, Bentham was much more explicitly positive about it. In setting out the utilitarian position, where the primary concern was promoting the greatest happiness of the greatest number, he regarded representative democracy as the form of government most capable of achieving this end. Bentham stated this clearly:

The only species of government which has or can have for its object and effect the greatest happiness of the greatest number, is, as has been a democracy . . . The only species of democracy which can have place in a community numerous enough to defend itself against aggression at the hands of external adversaries, is a representative democracy.

Quoted in Christophersen 1966: 97

In contrast to the fears held by apologists of the ancien régime, Bentham strongly asserted that democracy was best suited to providing the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. The utilitarian emphasis on the individual would also play a role in supporting the extension of the franchise, and in Resolutions on Parliamentary Reform Bentham was well ahead of his time in calling for universal suffrage and the secret ballot. ‘I have not that horror of the people . . . I do not see in them that savage monster which their detractors dream of,’ he wrote (quoted in Graudbard 1973: 662).

The fourth major line of reasoning in support of democracy came from nationalists, with the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini being the most prominent exponent. For Mazzini, ‘the great democratic idea which guides the world’ was closely connected to a specific form of universal nationalism, a cosmopolitan vision of separate republican nations collectively living together in harmony, separately contributing to a common good (Mazzini 2001: 8). ‘Our principle of the People’, Mazzini explained, ‘is simply the application of the doctrine of humanity to every nation’ (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 108). This differed from the cosmopolitanism of liberals: ‘For us, the end is humanity; the fulcrum, or point of support, country. For Cosmopolites, then, I freely admit, is also humanity; the fulcrum or point of support, is man – the individual’ (Mazzini 2001: 68; original emphasis). He argued that by purely focusing on liberty as an end in itself, and on the individual shorn from the nation, the emerging liberal conception of democ-racy was incomplete. Interestingly, there was also a strong spiritual dimension to Mazzini’s thought, as he regarded the establishment of democracy in separate nations as part of God’s plan:

When the arms of Christ, even yet stretched out on the cross, shall be loosened to press the whole human race in one embrace – when there shall be no more pariahs nor Brahmins, nor servants nor masters, but only men – we shall adore the great name of God with much more love and faith than we do now. This is democracy in its essentials . . .

Mazzini 2001: 10; original emphasis

Combating the position of apologists such as Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre, who powerfully argued that democracy was against the will of God, Mazzini instead proposed that it was the form of government most capable of fulfilling God’s plans for humanity. That democracy took on a messianic quality in Mazzini’s thought is illustrative of its growing significance and acceptance.

While the international order founded at Vienna may have prevented war between the great powers, it was less successful at repressing popular doctrines. Ongoing nationalist struggles and domestic unrest would ultimately peak with the 1848 revolutions. The ‘springtime of the peoples’ was both a high point for contestation over democracy in the nineteenth century (Christophersen 1966: 323) and a defining moment in the trajectory of popular sovereignty.

1848: ‘The Turning Point at Which Modern History Failed to Turn’

The attempt to restore the ancien régime was looking increasingly shaky by the 1840s. France had become a constitutional monarchy, Austria was led by a handicapped emperor, nationalist sentiment continued to grow across the continent, while food shortages and poor harvests combined with pressures caused by significant socio-economic changes to place great stress on Europe’s rulers. In November 1847, the Swiss civil war resulted in a victory for liberal forces following Prince Metternich’s failed attempt to mobilise a reactionary coalition. The weakness of the ancien régime was readily apparent, as was the possibility for serious change. The revolutions of 1848 began in January in Sicily and soon extended to other parts of Italy. A crucial development was unrest spreading to France, ‘the great factory of revolutions’, as Metternich put it (quoted in Bertier de Sauvigny 1962: 262). The barricades appeared on 22 February, and it was not long before King Louis-Philippe abdicated, taking with him the last vestiges of the French monarchy. Within months revolution had swept across the continent, engulfing France and the German and Italian states, as well as most of the Habsburg Empire. The situation was unhappily observed by François Guizot, who had been the French prime minister until the revolutionary turmoil had arrived:

Chaos is now concealed under one word – Democracy. This is now the sovereign and universal word which all parties invoke . . . Such is the power of the word Democracy, that no government or party dares to raise its head, or believes its own existence possible, if it does not bear that word inscribed on its banner . . .

Guizot 1849: 2–3

Democracy played a central part in the tellingly named ‘springtime of the peoples’. Increasingly it came to embody the demand for greater social change, due to its classical connotations of equality and levelling. Retained were the associations of social rule, only now the majority were identified as the poor working class. For many, the revolution was seen as incomplete if it did not extend to address socio- economic relations. In this sense, democracy came to be understood as an ‘economic ideal and expressed the idea that the 1848 Revolution had to be pushed further’ (Dupuis-Deri 2002: 282). These incipient social demands linked to democracy meant that liberals remained very wary, if not outright opposed to it. Reflecting on the revolutionary events he witnessed and participated in, Alexander Herzen acutely identified the halfway position of liberals: ‘They want freedom and even a republic provided that it is confined to their own cultivated circle. Beyond the limits of their moderate circle they become con-servatives’ (quoted in Ellis 2000: 49). Liberals soon allied themselves with conservatives, fearing that any further changes might threaten property.

The economic and social demands expressed through the concept of democracy meant it would be more closely linked with socialism and communism. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon explicitly stated that democracy and socialism were synonyms, while Friedrich Engels went even further in announcing that, ‘nowadays, democracy means communism’ (quoted in Christophersen 1966: 294). Indeed, some of the loudest calls for democracy emerged from those representing and supporting the proletariat. In the immediate period leading up to the outbreak of the 1848 revolutions, there was a movement of Chartist Internationalism (Weisser 1971), which was an important precursor to the Communist Internationals. Perhaps the most notable group were the London- based Fraternal Democrats, with which Karl Marx and Engels were associated. The aim announced in their manifesto was ‘to advance the cause of DEMOCRACY and promote THE FRATERNITY OF NATIONS’ (Mazzini 2001: 92). Writing in the Chartist newspaper the Northern Star, Engels recounted the speech of the ‘ultra- democrat’ leader Alexandre Ledru- Rollin at one of the republican banquets in Paris:

There is at this moment a great movement going on in Europe amongst all the disinherited, who suffer by heart or by hunger. This is the moment to console them, to strengthen them, and to enter into communion with them. . . . Let us, then, hold a congress of Democrats of all nations, now, when the congress of kings has failed!

Engels 1848

Engels’s call for a ‘congress of democrats’ reflected the upsurge in socialist and communist movements across Europe, many of which actively adopted the label: the Société démocratique française, the Association démocratiquein Belgium, the Democratic Committee for Poland’s Regeneration, and another society in London, the Democratic Friends of All Nations. Marx and Engels also explicitly used the term in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, published in 1848. They announced that ‘the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class to win the battle of democracy’ (Marx and Engels 1848).

Recognising the growing centrality of the concept, and undoubtedly influenced by his experiences in America, Tocqueville was a notable exception in trying to challenge democracy’s associations with these more radical doctrines. Speaking to the French Constitutive Assembly, he sought to wrestle back control of the concept: ‘Democracy and socialism are linked only by a word, equality; but the difference must be noted: democracy wants equality in freedom, and socialism wants equality in poverty and slavery’ (quoted in Dupuis-Deri 2002: 284–5). Rather than being synonyms, in his rendering socialism became a counter- concept for democracy. Appreciating the political power of the concept at that moment, Tocqueville was no longer hesitant about advocating for democracy. He proclaimed that he wanted a French republic ‘entirely democratic without being socialist’ (quoted in Dupuis-Deri 2002: 284–5). This contestation over the meaning of democracy was representative of the pivotal role it played in political discourse during the 1848 revolutions.

In 1848 France was not the same disruptive force it had been in 1789, but it was still at the revolutionary forefront, especially in regards to developments related to democracy. One of the most important decisions made by the provisional government on assuming power was granting the vote to all male French citizens over the age of twenty-one, which enlarged the electorate from approximately 246,000 to almost 10 million (Fortescue 2005: 99). This was the first time that universal male suffrage had been instituted in a major European state.2 Historically it had been the system of lot that defined democracy; now increasingly it would be the ballot. This change can be witnessed in the words of Alphonse de Lamartine, the president of the provisional government: ‘By what procedure do citizens all participate by entitlement in government and legislation? By universal suffrage. Universal suffrage is, then, democracy itself’ (quoted in McManners 1966: 400). Notably, a wide range of influential commentators and politicians – Lamartine, Tocqueville, Guizot, Renan, Proudhon, Carlyle, Marx, Engels and John Stuart Mill – all identified France as becoming a democracy in 1848 (Christophersen 1966: 318). Reflecting this shift, the provisional government proclaimed that it was their job to secure ‘the democratic government that France owes to herself’ (quoted in Dupuis-Deri 2002: 285).

The provisional government’s identification of France as a democracy extended to its dealings with other states. This can most clearly be seen in the Manifesto on Europe, issued on 4 March 1848 by Lamartine. The document announced that France sought peace, but that it would not tolerate any external interference and it was strongly opposed to attempts by foreign powers to suppress nationalist revolts elsewhere. The French republic was ‘desirous of entering into the family of established governments, as a regular power, and not as a phenomenon destructive of European order’ (Lamartine 1849). Lamartine refuted the Holy Alliance’s claim that the internal makeup of states was a concern for all:

France is a republic. The French republic does not require to be acknowledged in order to exist. It is based alike on natural and national law. It is the will of a great people, who demand the privilege only for themselves.

Lamartine 1849

Contra Metternich, Lamartine argued for a reciprocal right of non- intervention: each state should be free to determine its own constitution reflective of its own identity and history, and should allow others to do likewise. In seeking to assuage fears that France might soon become a ‘violent democracy’, Lamartine stressed that popular rule did not pose the threat it had previously, observing that ‘democracy at once spread terror among thrones, and shook the foundation of society. But now, on the contrary, both kings and people are accustomed to the name, to the forms’ of popular rule (Lamartine 1850: 45). The provisional government identified France with the popular principles of the first French revolution, but did not regard this as problematic: ‘It is determined never to veil liberty at home; and it is equally determined never to veil its democratic principle abroad’ (Lamartine 1850: 45). The French manifesto was not particularly amenable to the conservative powers, but they soon had bigger problems to worry about as revolution spread further, with clashes in Vienna, Budapest, Venice, Cracow, Milan and Berlin.

Elections for the French Constituent Assembly were held on 23 April 1848, with the more radical republicans and socialists being roundly defeated. To the surprise of many, universal male suffrage had resulted in a clear victory for conservative and more moderate liberal forces, who successfully countered the threat of ‘ultra- democrats’ and others demanding more far- reaching social changes. This outcome was particularly significant, as it demonstrated that democracy in the form of universal suffrage was not as dangerous to established interests as had previously been assumed. This observation would be further reinforced by the experiences of the second and third Reform Bills in Great Britain. Reflecting on these changes in Unforeseen Tendencies of Democracy, Edwin Godkin later suggested that the extension of the franchise in a large state actually worked to dilute its impact, thereby reducing the risks of mass democracy (Godkin 1898: 60–1). In this sense, it was gradually becoming apparent that the more moderate American experience was a better guide for judging the consequences of democracy in modern times than the turmoil and strife of the first French revolution.

The limited nature of France’s revolutionary experience of 1848 was echoed across the continent. Elsewhere there were new constitutions, changes of government and abdications of monarchs, but the ruling houses were not overthrown. The collective fate of the revolutions was sealed by stopping ‘at the foot of the throne’ (Sperber 1994: 115). It was not long before the tide began to turn, with conservative forces regaining the upper hand by 1849. In Austria a new emperor was in power and quashed nationalist uprisings; meanwhile the republican movement had failed in Italy, and the attempt to unite the German states fell short when the Prussian king refused ‘a crown from the gutter’. With Louis-Napoleon’s coup d’état in France on 2 December 1851 conservatives had reasserted control across Europe. Popular hopes raised by the ‘springtime of the peoples’ had been dashed. Proudhon lamented the missed opportunity: ‘Yes, we have been beaten and humiliated. We have all been scattered, imprisoned, disarmed and gagged. The fate of European democracy has slipped from our hands – from the hands of the people – into those of the Praetorian Guard’ (quoted in Ellis 2000: 45–6).

The 1848 revolutions were memorably described by G. M. Trevelyan as ‘the turning point at which modern history failed to turn’ (quoted in Rude 1972: 262). This observation seems particularly apt when considered in reference to international politics. Turmoil swept across the continent, but the general war that many feared would attend a revolutionary outbreak failed to eventuate. France did not go on the march and unaffected states chose not to try to take advantage of the general unrest. The overarching international framework constructed at Vienna may have held firm, but the events confirmed that the attempt to defend monarchy through rebuilding historical right and establishing principles of legitimacy could not succeed. Reflecting on the outcome of the revolutions, Thomas Carlyle observed that ‘the world does believe it; that even Kings now as good as believe it, and know, or with just terror surmise, that they are but temporary phantasm Playactors, and that Democracy is the grand, alarming, imminent and indisputable Reality’ (Carlyle 1850: 12). In the short term, the forces of reaction had won the day, but maintaining the status quo was clearly gone as a long-term option, especially as the political and social trends towards democracy continued to gather pace. The result was an uneasy truce between conservative and popular forces. And so, like Marx’s old mole, popular sovereignty had yet to fully supplant monarchy, but its time was fast approaching.3

Dealing with the Inevitable: Democracy in the Late Nineteenth Century

It was not long after the inconclusive ‘springtime of the peoples’ that conflict would again shape the trajectory of democracy, only this time in the United States. Given that America was regarded as the great litmus test for democracy, the civil war was a crucial moment: were the sceptics right? Would America’s experiment prove to be a fatal and short- lived mistake? The breakdown of the union seemed to confirm suspicions that the United States was not so different from Europe, and that democracy remained an unsustainable and volatile form of rule. In this regard, the British reaction is instructive, given that it had the progressed the furthest towards democracy out of any major powers. The situation in the United States was taken as a strong argument against further altering the balance of the British constitution towards the people. Reflecting on the outbreak of the civil war in 1861, The Times suggested that ‘it is not too much to say that the form of democracy which has taken for the last thirty years, or since the Presidency of Jackson, was likely to lead to such a result’ (quoted in Roper 1989: 111–12). Blackwood’s was more explicit in its conclusions: ‘Every sensible man in this country now acknowledges . . . that we have already gone as far toward democracy as is safe to go’ (quoted in E. D. Adams 1925: 393). This was echoed by the Saturday Review:

In that reconstruction of political philosophy which the American calamities are likely to inaugurate, the value of the popular element will be reduced to its due proportions. . . . We may hope, at last, that the delusive confusion between freedom and democracy is finally banished from the minds of Englishmen.

Quoted in E. D. Adams 1925: 387–8

Prominent liberals such as William Gladstone conceded that the turmoil in the United States was of grave consequence, writing as 1861 came to a close: ‘This has without doubt been a deplorable year for poor “Democracy” and never has the old woman been at a heavier discount since 1793’ (quoted in E. D. Adams 1925: 389). The Earl of Shrewsbury was less sanguine: ‘I see in America the trial of Democracy and its failure’ (quoted in E. D. Adams 1925: 389). The Times concurred: ‘The theories attributing immeasurable superiority to Republican forms of government have all been falsified in the plainest and most striking manner’ (quoted in Grant 2000: 40). Talk of democracy’s demise in the United States would prove distinctly premature, however.

Just as the collapse of the United States into civil war was taken as a clear warning against further democratisation, the subsequent victory of the North would soon be taken as additional evidence that the advancement of democracy was ‘inevitable’. This was not the first time, and certainly not the last, that the outcome of war would play a decisive role in the historical development of democracy. The survival of a democratic United States was important in at least two respects.4

First, as a result of the conflict becoming about the abolition of slavery, the North imbued democracy with moral purpose (Roper 1989: 86). In doing so, it continued the process identified above of democracy’s meaning expanding, coming to represent not just a set of institutions but also a set of values and ideals. This was best conveyed by the great American poet of democracy, Walt Whitman: ‘According to you, dear friend, democracy is achieved if there are elections, politics, various party slogans, and nothing else. As for myself, I believe that the present role of democracy begins only when she goes farther and farther’ (quoted in Roper 1989: 95). The second significant consequence of the United States surviving, and subsequently thriving in the reconstruction era, was that it maintained its role as the vanguard of democracy. Illustrative of this is Abraham Lincoln’s famed Gettysburg Address. Delivered when the nation was in the depths of the war, still today it is taken by many as providing the perfect encapsulation of democracy’s essence: ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’ (Lincoln 1863).

The continuation of America’s great experiment with popular rule strengthened a growing perception in Europe that the rise of democracy – in one form or another – was inevitable. Matthew Arnold reflected that ‘at the present time, almost everyone believes in the growth of democracy, almost everyone talks of it, almost everyone laments it’ (quoted in Bell 2007: 31). Henry Sumner Maine would make a similar observation:

Nine men out of ten, some hoping, some fearing, look upon the popular government which, ever widening its basis, has spread and is still spreading over the world, as destined to last for ever, or, if it changes its form, to change it in one single direction. The democratic principle has gone forth conquering and to conquer, and its gainsayers are few and feeble.

Maine 1886: 5

Commenting on the Third Reform Act of 1884, which added another six million men to the British electorate, Sir Wilfrid Lawson proclaimed that ‘the great tide of Democracy is rolling on, and no hand can stay its majestic course’ (quoted in Maine 1886: 69). This growing sense of inevitability in democracy’s rise represented an adoption and extension of Tocqueville’s analysis: rapid socio-economic changes were driving moves towards democracy in the political sphere.

Many commentators may have been fixated on the rise of democracy, but in reality its ascent took place within confines set by the increasingly dominant doctrine of liberalism. Indeed, it was through attempting to reconcile this seemingly inevitable trend towards democracy with established interests that the liberal democratic form would ultimately crystallise (C. Hobson 2009). Liberals sought to protect the rights of the bourgeoisie from the unfettered powers of kings on one side and the increasing demands of the working classes on the other. Constitutions, parliaments and representation were not simply a way of restricting the powers of monarchs; they also worked to grant more power to the people while limiting the most dangerous dimensions of democracy. As previously noted, representation effectively answered the two main concerns that had long dogged democracy: that it was impossible, and that it was undesirable. Representation allowed for popular rule over a larger territory, while also enabling the people to participate in government and legitimate power, albeit in a more restricted and indirect manner than in ancient democracies. A pivotal figure in completing this conceptual shift was John Stuart Mill, who built on the innovations of Madison, Sieyès and Paine. Mill argued that ‘a completely popular government is the only polity which can make out any claim’ to being ‘the best form of government’ (John Stuart Mill 1991: 244). No longer was democracy distinguished by being direct or not, Mill instead identified a democracy as ‘true’ or ‘false’ by its kind of representation: whether it represented all the people or the majority only (John Stuart Mill 1991: ch. 7). This reflects a gradual, but significant, shift in which democracy became more politically acceptable and desirable through having its most challenging dimensions – extensive participation, greater social equality – removed or limited. Before Woodrow Wilson sought to make the world safe for democracy, there had been an earlier process of democracy being made safe for the world.

The second half of the nineteenth century represents a period of transition between monarchical and popular sovereignty. The rise of representative government was at the heart of a more general liberal constitutional movement, which operated to restrict both executive and legislative powers. As Gianfranco Poggi explains:

The system of representative government which . . . marked the distinctive nineteenth-century advance in the career of the modern state, deliberately fostered the anti- absolutist legacy of earlier constitutionalism by laying explicit boundaries around the action of state organs, including elective legislatures.

Poggi 1990: 57

The advancement of the liberal programme acted to further undermine monarchic sovereignty, in that the power of kings and queens was now limited by constitutions. Even if more monarchs now explicitly ruled by the grace of the people, wherever constitutions and parliaments had been instituted a fundamental concession had been made to popular sovereignty. Constitutionalism came to represent an important element of the classical ‘standard of civilisation’ that determined full membership in international society, whereby ‘civilised’ states were distinguished from ‘semi- civilised’ and ‘uncivilised’ outsiders that were denied full sovereignty (Gong 1984). As Ido Oren notes, before the First World War there was ‘a select group of states – modern, constitutional, administrative, cohesive nation- states’ that were seen as the most developed, and the difference between them ‘and the rest of humanity was perceived as far greater than the differences among members of the group themselves’ (Oren 1995: 155). Constitutionalism became an important marker of being ‘civilised’, which helped lay the foundations for the later conceptual transformation in which authoritarian rule was identified as illegitimate and ‘uncivilised’.

Democracy and Empire

Another important aspect of the standard of civilisation was the role it played in justifying imperial expansion and colonialism. In this regard, two of the most significant trends of the second half of the nineteenth century were first, the rise and consolidation of popular sovereignty in Europe, and second, the dividing up of the ‘barbarian’ world by ‘civilised’ great powers. While both phenomena have separately been examined in detail, much less attention has been given to the linkages between them. Writing in 1898, William Lecky was one of the few to openly consider them in tandem: ‘It is, indeed, most curious to observe the passion with which nations that are accustomed to affirm the inalienable right of self- government in the most unqualified terms have thrown themselves into a career of forcible annexation in the barbarous world’ (Lecky 1899: 480). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, democracy and empire were generally not considered a contradictory pairing, however. Colonised peoples were regarded as savages or barbarians, and hence not capable of self-determination. Quite simply, few Europeans entertained the possibility that popular sovereignty could, or should, apply to others. F. J. C. Hearnshaw argued that while that the British dominions had been given a ‘unique opportunity for democratic development’, this could not be extended to the empire’s uncivilised dependencies: ‘In countries where the people is still ignorant, primitive, divided and inarticulate . . . democracy is not a good form of government; it is not, indeed, a form of government at all, but merely a delusion’ (Hearnshaw 1920: 151). James Bryce was equally dismissive of ‘backward races’ having democracy: ‘it is as if one should set a child to drive a motor car’ (Bryce 1921b: 549).

An interesting dynamic could be found in the British Empire, whereby different degrees of democratic government were identified as existing in various parts. One commentator observed that ‘the main dividing line is between self- governing dominions and dependencies. The former are more democratic than the mother country; the latter, in outward appearance and institutions, know little or nothing of democracy’ (Lucas 1916). The dominions were actually at the forefront in democratic experimentation, with New Zealand and Australia the first places to give women the right to vote and to stand for office. As with the United States, the relative blank slates they commenced with offered something of a testing ground for popular rule. Given the sense of inevitability in democracy’s rise, the dominions were seen as under-taking valuable ‘democratic experiments’ that would help ‘to solve the problems with which we know we must deal’, as the author of Our Colonial Empire noted (quoted in Bell 2007: 23). In this sense, the British dominions played a similar role to that which Tocqueville had assigned to the United States. It was partly for such reasons that Franklin Henry Giddings in Democracy and Empire suggested a synergistic relationship existed between the two: ‘Democracy and empire, paradoxical as such a relationship seems, are really only correlative aspects of the evolution of mankind’ (Giddings 1900: v). This relationship was not as benign as Giddings suggested, however. It is necessary to emphasise that the supposed terra nullius that allowed for the founding and successful democratisation of these settler societies was ultimately premised on displacing indigenous communities and dispossessing them of their land (Mann 2005: ch. 3).

Not only did the dominions provide a testing ground for democracy, the British Empire offered a crucial safety valve for managing popular pressures at home. The material benefits that flowed back to the imperial core helped in reducing unrest among the growing working and poorer classes (Bell 2007: 2). Imperial conquest also provided a useful distraction and was a way of strengthening national identity and a sense of common purpose. Furthermore, in the domestic contest between conservatives and radicals over the extension of political rights, both sides drew on arguments related to the empire. Conservatives argued that the demands of maintaining the empire, so crucial to Britain’s international standing, warned against greater popular participation. This reflected a belief that democratic control should not be extended to the realm of foreign policy. Conversely, ‘British liberals and radicals consistently conceived the case for extending the franchise at home in terms of a contrast with colonial subjects whose incapacity for participation in political power they deemed self- evident’ (Pitts 2005: 249). Emphasising the gap between British and colonised subjects was a way of minimising perceived differences between enfranchised and disenfranchised groups within Britain. In this way, the extension of the vote to the lower classes and women was assisted by comparison with colonial subjects. Understood in this manner, the simultaneous growth of democracy and empire appears less paradoxical, instead being related phenomena. The democratisation of Great Britain in the nineteenth century, often taken as a paradigmatic case (Zakaria 2007: 48–51), was underwritten by its empire.

Conclusion

The history of political and state theory in the nineteenth century could be summarized with a single phrase: the triumphal march of democracy. No state in the Western European cultural world withstood the extension of democratic ideas and institutions.

Carl Schmitt (1985: 22)

At the Congress of Vienna the new international order was constructed against the popular doctrine that had emerged from revolutionary France. Democracy was widely derided and stigmatised, with the dam-aging memories of Jacobin excesses compounding deep- seated fears inherited from the classics. Yet, as Eric Hobsbawm concludes, ‘rarely has the incapacity of governments to hold up the course of history been more conclusively demonstrated than in the generation after 1815’ (Hobsbawm 1962: 109). While the international order constructed at Vienna was able to endure, conservative attempts to re-establish monarchy based on principles of legitimacy were ultimately unsuccessful. Like the proverbial genie in the bottle, once released the principle of popular sovereignty could not be fully contained. In this regard, the revolutions of 1848 paradoxically were both a high and a low point for democracy. It achieved a prominence not before seen in modern politics, to the extent that François Guizot complained of ‘the empire of the word Democracy’ (Guizot 1849: 6). Yet it was more like a wave that peaked and soon receded, as the revolutions failed to be definitive.

In the second half of the nineteenth century democracy continued to grow in prominence and significance. It took on a range of multiple, sometimes conflicting meanings; democracy was understood in political, economic, social and even messianic terms. For some, it was still a classical polity, for others it was a representative form of government. The political understanding increasingly centred on suffrage, and hence the representative system, which was underpinned by the doctrine of popular sovereignty. Meanwhile, many socialists regarded democracy’s longstanding connotations of social equality as giving it significance for the proletariat’s struggle. For others still, it even began to take on a more abstract, ideal quality. Writing in 1852, Louis Auguste Blanqui despairingly summarised the situation: ‘So, tell me, please, what is a democrat? This is a vague word, banal, without any specific meaning, a rubber word. . . . Everyone claims to be a democrat’ (quoted in Dupuis-Deri 2002: 286; original emphasis). That democracy was becoming a ‘rubber word’ reflected its growing centrality in political discourse. In this regard, Carl Schmitt suggests that democracy had been able to maintain a more fixed meaning when it was primarily a counter- concept directed against monarchy, but ‘as its most important opponent, the monarchical principle, disappeared, democracy itself lost its substantial precision’ (Schmitt 1985: 24). This is part of the story, but the process was more dynamic: with its growing significance, it also became more politically valuable and thus further contested.

In the late nineteenth century popular sovereignty slowly but surely supplanted its monarchical predecessor in Europe. Liberal constitutionalism worked to restrain the powers of the monarch while keeping the proletariat at bay. Democracy’s seemingly inevitable rise was channelled through the representative system, being heavily shaped by liberalism, which worked to control many of its most threatening features.