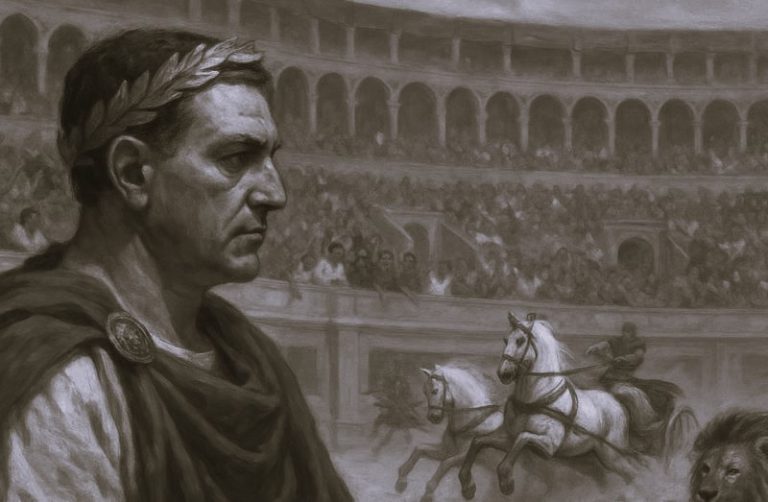

The images were meant to communicate messages about their persona and the general outlines of their reign.

By Dr. Anne Wolsfeld

Historian

Saxony-Anhalt State Office for the Preservation of Monuments and Archeology

State Museum for Prehistory

Abstract

Contrary to literary tradition, reactions to Nero’s Rome in the archaeological record of visual representation do not completely reject previous developments, but are multifaceted. In their self-representation the Flavians had different strategies to cope with their predecessor’s images: they used the official concept of the portrait head to make statements against his rule and also to support the consolidation of their family. For the other iconographic elements and dimensions of imperial images, which were chosen by the commissioner of the respective monument, a continuous and stepwise development can be observed, even for those elements newly introduced under Nero. Apparently, there was no impulse to move backwards to a more traditional level, not even after the death of a condemned emperor like Nero.

Introduction

In Roman historiography, Nero, who marks the end of the Julio-Claudian era, and his successor Vespasian, the founder of the Flavian dynasty, are portrayed very differently. In contrast to Vespasian, victor in Judaea and restorer of peace after the civil war of 69 CE, the vices and failings of condemned Nero appear even more unforgivable and inappropriate – a behaviour unacceptable for a Roman emperor.1 The authors of these historical writings, especially Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, were part of the Roman aristocracy, which in turn implies that they had very specific expectations of the princeps and his virtues regarding the still valued Roman Republican traditions.2 In order to restore their honour, after their views and political position have been jeopardized, they aimed at depicting those emperors as mali principes and criticizing their seemingly more unconventional and non-traditional activities as befitting a tyrant.3

Because of the frequent bias of historiographical accounts – in particular those from the time following a malus princeps, as in the case of Nero – it seems promising to have a look at other contemporary representational media (e.g. public performance, archaeology, epigraphy, numismatics), and thus to allow for an expanded and differentiated view of the emperor’s image.4 From these different media, this paper will focus on portraits, as they played a key role in the visual representation of the emperor. They were omnipresent throughout the empire, as we learn from a passage by Fronto.5 Furthermore, they were created with a representative purpose and as such they did not simply inform about the emperor’s appearance, but were meant to communicate positive messages about his persona and the general outlines of his reign in a decisive and visually persuasive way.6 And, most importantly, as contemporary creations, they are a primary source of the views of the commissioners on the emperor and his rule. Thus, portraits provide valuable evidence for the reconstruction of the image of the emperor and its understanding within the socio-political context of the principate – especially when historiographical evidence stylizes untraditional principes as autocratic maniacs to contrast them with ‘good emperors’.7

After Nero’s damnatio memoriae, Vespasian was confronted with 80 years of Julio-Claudian representation. He had to decide on his policy and imagery in relation to the Julio-Claudian representation in order to establish himself and a new dynasty. How did he deal with his condemned predecessor’s images and how are his family’s portraits characterized compared to those of Nero? Can contrasts be detected similar to those implied by literary evidence? We should do more than contrast the more obvious emperors Nero and Vespasian. Since Nero as well as Titus and Domitian were of a young age when they succeeded an older emperor, are there any parallels in their imagery? Looking for breaks and continuity in imperial imagery from Nero to Domitian informs us about the acceptance and failure of certain iconographic elements and the introduction of new motifs. As much discussed evidence of Neronian self-representation, one other potential and exceptional monument, the Sol colossus, and Flavian responses to colossal dimensions and unconventional iconography will be examined in a case study at the end.

Finally, with a wider perspective, we ought to inquire how the characteristics of Neronian and Flavian imagery are to be interpreted not only in regard to each other, but in the context of the history of visual representation of the principate.

Portraits as Visual Medium

In all images representing the imperial family, i.e. statues, busts, reliefs, coins, the appearance of the portrait head constitutes the constant and essential part of the image. Established throughout the empire with an astonishing typological homogeneity, thus assuring recognition, we must conclude that for each portrait type there was a prototype serving as the role model for the replicas that have come down to us.8 Because of this standardization throughout the empire, we may assume that the prototype was commissioned in Rome, with the emperor not necessarily involved, but at the very least aware of its creation.9 From this point on it served as the model for the 2D version on the obverse dies of the imperial coinage, and the prototype could be distributed as plaster or clay casts to all parts of the empire, where the copying work was done by local sculptors.10

The other image-constituting iconographic elements, such as different costumes like the toga or the cuirass, as well as attributes like wreaths, weapons, etc., show a much greater heterogeneity and must have depended on the different views of the commissioning parties related to their social, political, and cultural context.11 Like the portrait head, the image bodies as such are semantic constructs from a variety of iconographic elements and convey specific, intendedly positive messages about the qualities of the represented person.12 They basically relied upon the common virtues and roles an emperor could and should assume. Most certainly commissioners throughout the empire were aware of the political atmosphere at Rome and the official image, which gave clues to the emperor’s preferences. The commissioning parties honoured the emperor and displayed their loyalty to support the princeps’ position by choosing iconographically variable images, either reflecting their expectations towards the princeps or meant as offerings suggesting new ideas to represent the princeps.13 Due to the different commissioners and various functions that portraits could assume, an appropriate evaluation always has to consider these contextual conditions and the prevailing conventions of visual ‘language’ (Bildsprache); off icial public monuments erected by the conformist Senate, for example, are very different from images in houses of private citizens, which can have a more freely chosen iconography.14

Thus the distribution and reception process of imperial images involved the emperor and his subjects, acting in different contexts, and was by no means a unilateral process. Given the medial function of images, imperial portraits should rather be considered as part of a communication system, albeit not a direct one, because the portraits commissioned by his subjects seldom reached the emperor himself, except maybe for those in Rome.15 By having a distinguished look at the different medial contexts, imperial images allow us to observe over a certain period of time the reactions of each involved party to some iconographic elements or roles: either they were gradually established in the iconographic conventions or they disappeared, thus showing the acceptance or failure of these elements.16

To sum up, the head prototype of Roman imperial portraits was created close to and with the approval of the emperor; thus it constitutes the most authentic source of imperial self-representation. Iconographic motifs on imperial coins also needed his consent for the coins to be issued. Even though motifs and types are likely to be chosen by the responsible mint magistrates as loyal and flattering offers to the emperor, they show a certain iconographical normativity serving the imperial and senatorial views.17 The following analysis will therefore focus on portraits and coins, as the most likely source of imperial self-representation, presenting a reliable basis for f inding out how the Flavian emperors and the leading political group responded to Nero’s Rome in imperial imagery in the first place.

‘Damnatio Memoria’:18 The Reworking of the Imperial Portrait

The most obvious public response to Nero and his rule was the tearing down of his images and their subsequent reworking into the portraits of his successors.19 For the analogous eradication of Domitian’s memory, for example, we have literary records showing vividly how passionately the citizens and most of the senators must have pursued this work of destruction.20 The idea of inflicting pain upon a stone work, conveyed by these literary sources, also illustrates how the portraits were treated as embodiments of the emperor’s person.

The reworking usually took place in the time immediately following the death of a bad emperor, but the portrait heads, often created for insertion into the statue body, could also be stored and used when needed, sometimes even centuries later.21 For Nero’s portraits, we have many examples that were reused for his Flavian successors.22 This is easily explained by the need for numerous portraits at a new emperor’s accession and the existence of the former, bad, emperor’s portraits, readily available to be reused. Additionally, the generous amount of marble required to create Nero’s opulent appearance made the reshaping into another portrait not that difficult. Finally, the contours of the Flavians’ portrait heads, with broad and fleshy facial features, were close to Nero’s, and may have enhanced or at least simplified reworking.

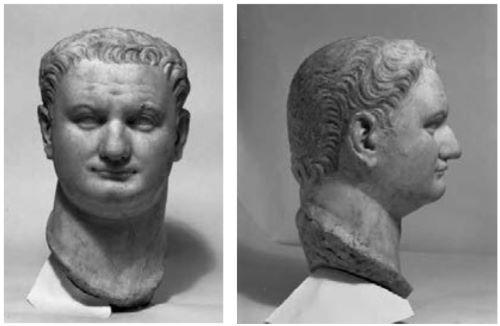

These are most likely the explanations for the fact that almost all copies of the early portrait types of young Domitian derived from Nero’s adult portraits (fig. 9.1a-b). Consequently, the reconstruction of the prototypes of Domitian’s portrait types as a prince is disturbed by remnants of Nero’s portraits.23 This is the case especially for those parts cut deep in the marble, such as the eyes, or for protruding parts like the nose, where the stone material for a complete working-over was missing. Among the typological elements, the front hair generally was the easiest part to copy, thus constituting a reliable identification marker, but only in combination with facial features.24

Reworked portraits often differ from the more reliable, newly created likenesses. Nevertheless, the occasionally awkward results of the reworked portraits apparently did not diminish the honour and reverence towards imperial images.25 Even convincingly reworked portraits often bear some traces of the old version at the back of the head, as the traces of the former emperor were seldom erased completely.26

The phenomenon of recycling portraits of condemned rulers has been described by Varner as ‘manifestations of the new emperor visu-ally cannibalizing the power and images of his defeated predecessor’.27 This interpretation is probably slightly exaggerated, but the reworking of portraits surely can be considered a visual statement towards the old regime, and in public places one must have been aware of the substitution of one imperial portrait by another.28 For the transition from Nero to the Flavians as his immediate successors, the reuse must have been all the more effective. The creation of the dynasty was made possible only by Nero’s defeat, as reflected by his reworked images and by contemporary literature contrasting Nero to the new and better emperor, Vespasian. Maybe the reworking can be best described as a kind of ‘conscious forgetting’ of the old regime, followed by the renaissance of the principate under the new ruler.29

In short, the practice of reworking portraits illustrates the importance of a visual manifestation of the ruler’s person through imperial images. In order to do so, the new emperor was in need of his own portrait type(s), with fixed iconographic features and characteristics, which were imposed upon his predecessor’s images or applied to newly commissioned ones. We will now take a look at how the Flavians coped with their predecessor’s portrait model, thereby positioning themselves in relation to Nero’s rule.

Alternating Trends in the First Century CE

Until 59 CE, Nero’s portrait concept30 (fig. 9.2) had basically followed the Augustan model with a simple coiffure (short strands of hair altered over the forehead with so-called fork-and-pincer locks) and classicist physiognomic features.31 Following the death of Agrippina and the dismissal of his counsellors, a major change occurred in Nero’s portraits, breaking with the imperial representation of the Julio-Claudians which had predominated the images of the Domus Augustana for nearly 80 years.32

On coins and in sculptures, Nero’s portrait now appeared with an artificial coiffure with long sickle-shaped locks, running from a fork near the right temple to the left side of the forehead, followed to the top of the head by a second row of locks running the opposite direction and forming a crest over the front row (fig. 9.3). The hair at the nape of the neck was worn longer and combed to the front on either side of the neck.

In addition to the coiffure, the emperor’s features had changed too: with a thick neck under a double chin and small eyes sunken in a fleshy face, he had transformed his whole appearance.33 With his next portrait type, prevailing from 64 to his death in 68 CE, these characteristics became even more pronounced, the face becoming even fatter and his hairstyle now featuring a row of sickle-shaped locks, all running to his left and forming a sort of crown at the front (fig. 9.4).34 Furthermore, some of his portraits, especially those on coins created after 59 CE, feature a short and neatly trimmed, fluffy beard covering mainly the cheeks; on marble portraits, it is occasionally painted instead of modelled plastically.35

Hairstyles with a pattern of waves on top of the head and accurately sickle-shaped locks are described in ancient literature as coma in gradus formata36 (‘hair arranged in tiers of curls’) and were styled with a curling iron. Because of the expenditure of time and care, such lavish hairstyles were associated with luxury and even with feminine behaviour. Consequently, because of Republican standards of modesty still relevant at this time, they were deemed inappropriate for male Roman citizens and were not used in their portraits.37 In her study of Neronian-Flavian male portraits, Petra Cain has shown that long, lavish hairstyles were originally worn by young male servants as an expression of juvenile beauty and wealth; only as the first century CE progressed did similar luxurious coiffures appear in portraits, mainly in those of young adults.38 Cain observed that after 80 years of static, monotonous, classicist imperial portraits, private citizens must have been eager for new forms of self-representation, going back not only to more realistic facial features, but also introducing a greater variety of coiffures like the coma in anulos or in gradus (‘hair arranged in ringlets or in tiers of curls’) to their portraits.39 According to Artemidoros, the idea of luxury, otium (‘leisure’) and well-being required for the care and styling of these coiffures was received positively.40 The introduction of these iconographic elements in representative portraiture was then allowed by a change in lifestyle, to be observed since the middle of the first century CE. The initially negative attitude towards a life of otium, restricted until then to the leisure time in private villas out of town, changed, and the lifestyle became even more popular in public domains in the city.41

In imperial portraits, there had already been a certain tendency to show ageing realism under Claudius, and even some attempts at hairstyles arranged in tiers. But Nero was the first emperor to use a very opulent form of the coma in gradus in his official portraits. Complemented by a fat face, especially in his last portrait type, as a sign of tryphé (‘lushness’, ‘indulgence’), he shows himself indulgent in a life of pleasure and of otium.42 Nevertheless, his facial traits are smooth and without wrinkles, and he is presented as the youthful ruler he in fact was. Like the coiffure, the short downy beard, growing in some of his portraits on the cheeks, can also be regarded as a sign of juvenile beauty,43 as it was worn exclusively by young men too old for their first sprouts of stubble. As this sort of beard necessitated effort, it resembles luxury coiffures.

After Nero’s death, the turmoil of the year of the four emperors saw different portrait concepts, which varied depending on the visual message one wanted to convey. For example, Otho followed Nero’s portrait style to show his allegiance to his predecessor. The visual messages were by now based on a wider pool of iconographic elements, introduced step by step into the portraiture of imperial Rome.44 Eventually, Vespasian would establish himself as the new ruler after Nero, and his choice of a portrait concept breaks with those of all his predecessors. This drastic change in iconography, which occurred with the founder of the new dynasty, has been much discussed and understood, surely correctly, as a clear distinction from the condemned predecessor Nero.45 Vespasian, already aged at the time of his accession, went back to the traditionalist model of the old men with wrinkles, a seemingly toothless mouth, and very little hair (fig. 9.5). Contrary to most of the Republican portraits of old men, Vespasian sports not a bony, ascetic, and yet somehow elegant facial appearance, but a broad-faced, old and unpretentious look.46 He thus represented the experienced and determined senior politician – in sharp contrast to Nero’s more inexperienced young age – without lacking a citizen-friendly impression.47

Thus, the immediate and natural response to Nero’s youthful and luxurious self-fashioning was the formulation of an ‘antithesis’ in Vespasian’s imagery,48 as founder of a new dynasty. All the more surprising is the reaction of the sons of Vespasian, who deliberately did not follow their father’s image, but again tried different iconographic paths. At first sight, such a decision could maybe be explained by their much younger age.49 But as can be observed with Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian, their portrait concepts had the intention of sending specific, well-considered messages with regard to their predecessors, crafted in the light of their socio-political positioning. For the iconographic choices of Titus and Domitian, it is therefore important to ask not only how they can be explained in the context of their family, but more so in relation to Nero, because he was the last youth to be represented in imperial portraiture before them.

Under their father’s reign, Titus and Domitian were presented differently from each other, each representation aiming at a concept appropriate to their age and position. Titus, the elder brother and successor to Vespasian, was portrayed with a more elaborate hairstyle, consisting of small ringlets (anuli), neatly arranged on top of the head and mixed with small sickle-shaped locks at the front (fig. 9.6). His rectangular facial contours are accentuated by the receding hair on the forehead, fleshy cheeks, and a double chin; his traits are animated with a frown, contracted and raised eyebrows, a slightly crooked nose framed by deep nasolabial folds, and slightly upturned corners of the mouth.50 Despite his more mature appearance, the hairstyle belongs to the aforementioned luxurious category that became fashionable at the middle of the century and was worn mainly by young men – but differing from the luxurious coiffure of Nero.51

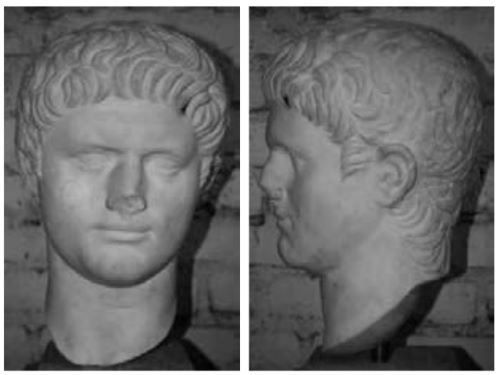

Domitian, on the other side, wears a coiffure reminiscent of Julio-Claudian family members like Germanicus or Drusus Minor,52 with flat strands of hair alternated at the front with fork-and-pincer locks (fig. 9.7).53 As far as we can reconstruct the prototype to his early portraits, his round face is young and smooth, with individual traits like straight eyebrows, a broad nose, and a large mouth.54

While Titus’s portraits sport a contemporary, stylish, and luxurious coiffure, Domitian’s leads back to the reliable hairstyle of the last ‘good’ Julio-Claudians before Nero; apparently, fork-and-pincer hairstyles of the Julio-Claudians were still considered wearable. Furthermore, these portraits may intentionally link the young Flavian to the positive memories of the legacy of the former dynasty; Domitian’s very young and promising age as well as his being a possible heir could have favoured an iconographical hint at figures like Drusus or Germanicus. Titus’s portrait type on the other hand, with a lush coiffure and downy beard style, as worn mainly by young men, evokes the contemporary lifestyle of pleasure and otium – a civil lifestyle that contrasts with his former military life.55

Like their father, they turned away from Nero’s late appearance: indeed, Titus featured a luxurious coiffure, but another type categorized by its ringlets, not yet known in imperial imagery,56 his face showing signs of corpulence, but not nearly so fat a face as Nero’s. The hairstyles of Domitian’s early portrait types can be seen in general as a reference to the Julio-Claudians, but they surely must be read in a positive way and thus not be paralleled with Nero’s first portrait types.

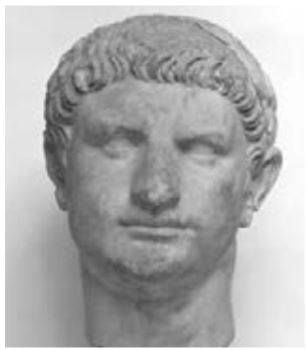

Then, following their accession to the throne, each of them picks up an appearance very similar to Nero’s later imperial representation. As a matter of fact, both Titus57 (fig. 9.8) and Domitian58 (fig. 9.9) start wearing the coma in gradus formata (‘hair arranged in tiers of curls’). Their facial traits are dominated by f leshy cheeks and a double chin, indicating not only a square skull but also a slight corpulence. However, in detail there are several differences between the portraits of the Flavian siblings and those of Nero. Apart from a less obvious facial fatness, the hair is arranged in a more moderate, less lavish way.59 Contrary to Nero’s portrait types, the gradus hairstyle of the Flavians was realized in different ways, owing to a greater variety of the arrangement and the shape of the strands of hair.60 For Titus’s and Domitian’s portraits the strands have their origin at the back of the head, from where long strands are then combed to the front, forming a wavy structure through alternation of direction on top. Compared to Nero, they form smaller and shallower segments, either leading directly into the front hair or laying in countermotion over the front row forming a small crest. The strands can either be discontinuous, with insertions of shorter locks or even ringlets, or they can run through from starting point to front hair.61 But mainly, the receding front hair of the Flavians together with a more appropriate length of hair at the neck and reduced corpulence gives them a less opulent appearance.

Commissioned in order to honour the represented person, the iconography of imperial portraits has to be understood in a positive way. Therefore, the similarity of Titus’s and Domitian’s portraits to Nero’s is unlikely to have been intended as an explicit reference to their condemned predecessor.62 As Petra Cain established in her study on Neronian and Flavian private male portraits, the coma in gradus was one of the current hairstyles of young men in the second half of the first century CE.63 Therefore, it seems likely that this choice for the Flavian siblings is due to the contemporary taste of portraying relatively young men, which thus supports the assumption of a continuity of fashion trends.64 Nonetheless, the message conveyed by the use of these iconographic elements stays basically the same since their introduction and, more importantly, there was no going back to the time before Nero’s reign and representation. Consequently, it was difficult to forget in such a short time period that Nero’s use of the coma in gradus and of a fleshy face were the utmost expression of pleasure and of a luxurious lifestyle.65 By applying these elements in a more moderate way to their accession portraits, Titus and Domitian were on the one hand able to distance themselves appropriately from Nero’s images, while keeping up with fashion trends. On the other hand, they could demonstrate their sympathy for a related and in the eyes of the Romans increasingly popular lifestyle, but with regard to fatness and opulence of hair not in such an exaggerated way.

To sum up, this choice of portrait concept did not occur immediately after Vespasian’s accession, relying until that point on uncompromised iconographic elements with the simple Julio-Claudian coiffure or the coma in anulos. Only after a certain amount of time and the increasing establishment of the new dynasty did Titus come up with an alternative and also in private portraits more often used version of luxurious hairstyle, which was imitated a couple of years later by his brother.66

Considering the strong reactions to the images and doings of condemned emperors, reported by archaeological or literary evidence, a visual distinction from the hated predecessor was recommendable, and this is precisely what Vespasian and his sons did at first. Obviously, after a certain period of time in which the counter-images promoted for Vespasian and his sons were followed, the iconographic elements of the coma in gradus in combination with fleshy faces seemed suitable again for imperial portraiture. This is supported by the fact that Domitian imitated his brother Titus’s portraits, which makes sense only if they were positively received by the contemporaries.67

After Domitian’s damnatio memoriae in 96 CE, his successors Nerva and Trajan saw themselves confronted with the same problem that Vespasian had to deal with in 69 CE: they had to decide on their iconographical relation to their predecessors, and they opted for completely different portrait concepts without explicit connotations of luxuria and otium.68

Having discussed the iconographic portrait concepts for each emperor’s rule from Nero to the last Flavian emperor, we shall now take a closer look at the importance of the Flavian family picture in contrast to Nero’s lonely reign.

The Visualization of Family Ties and Roles

With the redefinition of the imperial image, Nero broke not only deliberately with a long tradition of classicist iconographic concepts, but also with his predecessors and his family, by formulating his own new image. Thus, in a visual sense he stood apart. His dynastic rule was solitary as well, because unlike his predecessors, Nero never had children.69

After the death of Nero, Vespasian also went to drastic lengths to change the imperial image, this time to distance himself and his family from the condemned predecessor. As we saw, his example was not followed by the portraits of his sons for different reasons, but there is an important difference compared to Nero’s isolation in the Julio-Claudian line. The Flavian emperors, although they introduced several portrait concepts, were connected to each other visually through some kind of dynastic facial features (figs 9.5–9.7). In fact, they have in common a square skull with a high forehead, close-set eyes, a broad, arched nose with a slightly overhanging tip, and a thin long mouth, followed by a pronounced, pointy chin and a double chin. Of course, Vespasian and his sons were the first successive emperors with biological family links, with a chance of real resemblances. But even if Roman portraits can not necessarily be understood in the modern sense of ‘being portrayed’, there can be no doubt that the overall impression evoked by these physiognomic parallels must be considered a family likeness and that this was intended by the portrait strategies.70 Despite the differences in the portraits of father and sons, they are associated in an overall scheme through small details, representing them as a family union and setting them apart as an independent dynasty. The likeness of Titus’s and Domitian’s ruler portraits was not a random choice either (figs 9.8–9.9). Apart from the physiognomic resemblance, Domitian could have chosen any of the many possible hairstyles en vogue at that time, but he opted for exactly the same coiffure as his brother, altering only the variation in the front hair and the arrangement at the back of the head.71 The longer hair, combed toward the front from some low point at the back of the head or even from the neck, jokingly earned his haircut the term coma in adulescentia senescens (‘the ageing of my locks in youth’).72

The importance of a visual family connection through shared iconographic motifs is well documented for the Julio-Claudians from Augustus to Claudius – and even for the first years of Nero’s reign.73 For some of them, explicit assimilation by means of identical front hair motifs or facial features was used to mark the link in an even more obvious way, for example, in the case of Augustus and his selected heirs, Gaius and Lucius.74

In the case of Augustus, his adoptive sons and actual heirs successfully demonstrated for more than 80 years that a dynastic face can serve two purposes. In the first place, the visualization of a connection between different family members, which was not necessarily based on their real likenesses, signals concordia, the unity and mutual acceptance between these people and consequently the stability of their rule.75 At the same time, potential successors can be highlighted through typological analogies linking them to the ruler, indicating his providentia (foresight) by the early choice. These dynastic connections become even more evident in portrait groups, when images are not only assembled in the same place, but their belonging together is also supported by visual effects like a dynastic face.76 Therefore, it is no coincidence that Domitian, who apparently lacked his brother’s popularity at his accession, approached Titus’s image to show their family harmony, and therein to legitimize his position through the continuation of Titus’s rule.77

In terms of the creation of visual family connections, the Flavian emperors returned to the successful model of their predecessors, especially that of Augustus, counteracting the fate of Nero and the renunciation of his family. In the end, Domitian, as the last Flavian emperor, met the same fate as Nero. However, they had managed to stabilize their dynastic rule for nearly 30 years, and first Titus, and then Domitian, succeeded to their father’s throne as the first biological sons of an emperor coming to power in the history of the principate.

When we look more closely at the portraits and their facial expressions, a sequence in the choice of iconographic elements and in facial expression seems to be detected, maybe reflecting differentiated roles within the Flavian family. Nero’s nearly wrinkleless portraits show a relaxed face without much expression, the contraction of the eyebrows being accentuated a bit more only in very few portraits (fig. 9.3).78 Cain has observed that minimal facial expression and a wrinkle-free face had been a current phenomenon with young men and rulers, maybe indicating their youthful carefreeness and innocence.79 Therefore, in reaction to Nero, the portrait of Vespasian created the modest image of an old man with generically contracted and raised eyebrows and a vividly animated face (fig. 9.5). He is shown with the experience of age, determined to take action, and aware of his cura imperii (‘effort for the empire’).80

Contrary to other portraits of youths, both of Titus’s portrait types (figs 9.6 and 9.8) keep the stern and determined look with the raised and contracted eyebrows, probably as reminiscence of his father and express-ing similar concerns about the empire.81 But the modesty has gone, the portraits now showing a luxurious coiffure and a well-fed, still relatively young appearance. Finally, Domitian’s facial expression is calmer, and especially his accession type (fig. 9.9), following the coma in gradus of his brother, is nearly expressionless with horizontal eyebrows, no wrinkles at the forehead and gently resting lips. Like Nero, Domitian too is young and the relaxed facial expression appropriate. Compared to his brother Titus, they share the notion of luxury, which had become suitable again, but moreover Domitian can allow himself to be less severe and more relaxed. One seems to see the development of the Flavian portraits and their facial expressions as reflections of the principate’s situation from Vespasian, who restored the empire and finances after Nero and the war, to Titus, who shares his father’s concerns, but whose portraits are indicating an abundant and carefree continuation of the principate. Domitian in turn, as the second successor and the younger son, is promoting a worriless reign. The portraits of the Flavians and their facial expressions would thus respond to the changing, ameliorating situation and needs after the end of Nero and the civil wars.

This thesis of the visualization of the well-being of the rehabilitated empire after Nero can be supported by personifications on imperial coinage that echo an economic improvement.82 For the generally more extended repertoire of divinity coin reverses under Vespasian, motifs with personifications like Felicitas,83 Ceres,84 or Annona,85 increase, symbolizing the (regained) abundance and fertility underlined by attributes like cornucopiae or corn ears. These personifications reappear, with the same or with varied motifs, under Titus and Domitian.86 Under Vespasian and Titus, who actually were in charge of the rehabilitation of the economy, these motifs are issued amongst other more political topics, publicizing their efforts to stabilize the empire.87 Meanwhile, Domitian’s coinage highlights mostly his own military successes.88 The diminishing use of respective topics for their coinage could therefore be seen in connection with the seemingly increasing luxury and relaxed expressions in their portraits from Vespasian to Domitian.

In contrast to Nero’s solitary and heirless rule, which led to the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Vespasian constantly promoted very close family ties from the very beginning of his reign. Vespasian not only shared his power with his oldest son, Titus, but both his sons were presented on imperial coins as principes iuventutis (‘first among the youths’) from 71 CE onwards (fig. 9.10). In the first years of Vespasian’s principate they are shown together in important political and military roles.89 After 72 CE, Titus was honoured separately from his brother, with the same motifs used for his father, whereas Domitian, who had no part in the Judaean victory, was represented with a singular riding motif, but not without emphasizing his princely role by a sceptre crowned with a bust.90 Nonetheless, the family union was emphasized under Vespasian by the issuing of various coin series in the name of his sons, displaying their portraits on the coin obverses and attributing to them different roles on the reverses.91

Under Titus and Domitian, the family theme is less pronounced, caused no doubt by the fact that there were no male heirs to promote.92 One significant coin reverse from 80 CE emphasizes concordia between the two brothers, demonstrating how important a united and functioning family must have been.93 Then, of course, Domitian emphasized the commemoration of the Divi, serving to legitimize the successor’s rule. In fact, he was ruling as the son and brother of a Divus, thus compensating for his lack of the Flavians’ legitimating glory of Judaea. All in all, he relied fervently on family connections and also divinized his dead son and wife.94 After building the arch of Titus and the Porticus Divorum with the aedes Divi Vespasiani et Titi, he erected a monument to his family with the Templum Gentis Flaviae. Nero, on the other hand, had not managed to build a temple for his dead predecessor, Claudius; this temple was only finished under Vespasian.95 Contrary to Nero, Vespasian and his sons had realized how important the visualization of family ties was in order to secure a successful succession within the family line and the establishment of a dynasty.

The Reception of Nero’s New Images

With the resumption of the minting of aes in 64 CE, both obverse and reverse saw the introduction of some innovative iconographic elements and images, which inform us about the ideas developed for and close to the emperor.96 Nero’s portrait head, now showing the aforementioned later type ‘München-Worcester’ with unmistakable fatness and lavish coiffure, is enhanced by new attributes, the radiate crown and the aegis, indicated by the winged gorgoneion in front of his neck. These elements derive from godlike iconography, also known from the Hellenistic kings.97 Until then, such elements were reserved for the divinized emperor or restricted to the panegyric language of cameos and poetry. Whereas the aegis alludes to the princeps’ Jupiter-like rule of the world, the radiate crown can be understood as a solar attribute – originally belonging to the iconography of Sol – and as an honorary wreath at the same time.98 Moreover, the radiate crown was introduced for Nero on the same coin types as earlier for Augustus, added only after his divinization. This parallelism seems to raise Nero to the same level as a Divus.

There were other new images connected to solar symbolism and that alluded to Nero’s godlike status, which also appeared only in the late years of his reign in the off icial media. In her brilliant analysis, Marianne Bergmann shows that these solar elements must have been linked closely to his person and reign, because they disappear with his death.99 However, the more generally adaptable elements like the radiate crown as honorary wreath and the aegis become part of his successor’s, i.e. Vespasian’s, image on the obverse of his coins. Aegis and corona radiata were worn by the portraits of all three Flavians, but whereas these attributes featured as an exception for the coin portraits of Vespasian and Titus, they became a standard with the majority of Domitian’s images, sometimes even in combination on a single coin obverse (fig. 9.11).100 This evidence is rendered even more interesting because the imperial coins are likely to have been issued in consent with the emperor and the Roman Senate, thus respecting also the traditionalist views of the latter.101 This extensive use of iconographic elements with divine connotations suggests a wider acceptance by the Senate and the Roman people, thus admitting an elevated rank for the princeps. It seems that, once bestowed upon an emperor, such honours could not be withdrawn for his successors, but must be offered on an equal level.

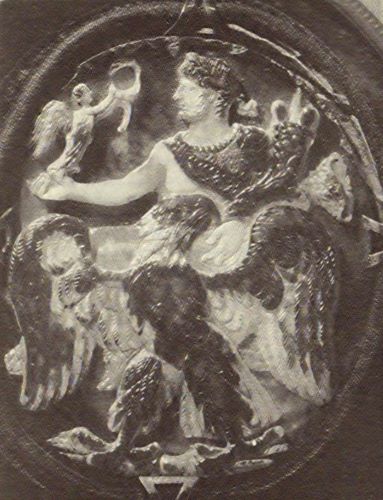

We should also have a look at another very prominent monument, which can be categorized as a symbol of Nero’s self-representation: the Sol colossus on top of the Vel i a, which stood in the vestibulum of the Domus Aurea, thus inside Nero’s home and not in a public space, even if it was surely visible from all over the Forum Romanum.102 As there is no evidence for an external commissioner, one must conclude that the homeowner chose its dimensions and iconography. About 30–35 metres high, it represented a naked Sol-like figure with a radiate crown, leaning on a support, with its right hand holding a steering rudder that rests on a globe (fig. 9.12). The latter attributes do not belong to Sol, but they allude to Fortuna, steering the fate of the world.103 The statue was completed not under Nero, but only under Vespasian, and it thus received not the head of the former emperor, but evidently a head of Sol. No direct evidence exists that suggests that the colossus should have represented Nero himself but, according to Marianne Bergmann, it most likely did and, most of all, people would have made that association.104

Vespasian’s response to this colossal and iconographically provocative statue of his predecessor in the guise of Sol was not immediate and total destruction, but rather alteration into a proper image of Sol; this gave it a new purpose.105 As mentioned above, this rededication could be best described as conscious forgetting: everybody must have been aware that it was intended as a statue of Nero and that it was finally reinstated as a statue of a real god.

The Flavians did not adopt the colossus for their own representation. Nevertheless, it seems to mark the passage to a new sense of dimensionality and an iconographic extension of imperial images. Compared to pre-Neronian times, there is more evidence for larger-than-life-size images of the emperor and his family in Flavian Rome itself, whereas proof in western provincial and Italian cities or the Greek east stays basically the same.106 Whereas no evidence can be securely located for the reign of Vespasian, who apparently and according to literature kept a low profile,107 the erection of larger-than-life-size images increases under Domitian,108 and climaxes between 89–93 CE with the dedication of another extraordinary monument to the living emperor: the equus Domitiani (fig. 9.13).109 Dominating the middle of the Forum Romanum with a height of approximately 12–15 metres, Statius reports that it was commissioned by the Senate and People of Rome as a monument honouring Domitian’s victory at the Rhine.110 Contrary to the Sol colossus of Nero, it must be classified basically as an official honorary monument, not as imperial self-representation – although we can be sure that such a monument as the equus was planned with the consent of the emperor.111

Since both the Sol colossus and the equus Domitiani are exceptional monuments in the image history of the city of Rome, an iconographic and contextual comparative analysis seems promising. In addition to its dimensions, the Sol colossus outshone all other known imperial statues erected in Rome since the Republican monuments for Octavian by its divine iconography.112 The crux is, however, that it was realized in Nero’s own home. Already in pre-Neronian times, there is evidence for images of the living emperor in a godlike (theomorphic) appearance, i.e. body types derived from the iconography of gods or heroes, commissioned in his honour in private and even public contexts throughout the empire. Some theomorphic types even increased in number under Nero and Domitian113 – but they did not make it into official imperial imagery supervised by the emperor and the Senate.114 Here, only isolated divine attributes succeeded, like the aegis from Nero’s reign or the thunderbolt from Domitian’s time onwards.115

Hence, iconographic conventions regarding the use of divine elements existed and depended on the medial context. This is most likely the main reason that may have led to the different appearances of the urban colossi of Nero and Domitian, despite their topographical vicinity: contrary to the colossus’ godlike body and attributes, Domitian’s statue wore a military travel garment (tunica and paludamentum), his sword resting at his side, while the horse had a hoof set on top of the head of the defeated Rhine. It straightforwardly communicated military victory, and the only supernatural element was a statuette of Minerva, which he bore on his left hand as his supporting goddess.116 Considering the contextual circumstances, the more conservative iconography of Domitian’s statue117 can be regarded as a compromise, for it was the Senate accrediting such a literally enormous public honour to Domitian. This is supported by the fact that in a very different context, at the compound of the Augustales at Misenum,118 another, more belligerent, riding statue of Domitian, endowed with divine symbols, could be created and even rededicated to his successor Nerva.119 However, the political centre of Rome’s honorary monuments – despite some enhancements – held on to the more traditional qualities of the emperor.

Unlike the Sol colossus, the equus maximus met another fate and was destroyed completely after Domitian’s death.120 The destruction of the equus illustrates not only another discontinuity in imperial representation, but also shows how decisive a look at the monument’s medial context can be. The off icials chose not to rededicate it to Domitian’s successor, but actually this was not solely due to its inappropriate dimensions or its iconography. It was more the problem of the location, since several years later, Trajan managed to have a very similar riding monument erected, but this time more discreetly, in the middle of his own newly built forum.121 Therefore, it can be assumed that the location in the honourable political centre of Republican Rome was at that time considered unsuitable for an emperor’s image (at least until the statue of Septimius Severus122). And contrary to the colossus, the equus could not be altered into a god’s likeness by the simple change of the head.123

Breaks and Continuity in Imperial Imagery

Considering the historical rumours about Nero’s madness and divine aspirations, one would assume that the more unconventional and trespass-ing iconographic introductions would have vanished with his death. It is beyond doubt that some immediate modifications were applied, such as the restructuring of the area of the Domus Aurea, the tearing down and the reworking of his statues, and the eradication of his name in inscriptions.124 However, those singular counteracts must not be over-simplified, because it is possible to gain a more differentiated view on the relation of Neronian and Flavian visual representation.

Based on the analysis of the portrait heads, commissioned in Rome and acknowledged by the emperor, we can conclude that conceptual changes could be easily taken into account to demonstrate either continuity or demarcation in regard to the predecessor’s rule.125 Whereas Nero and then Vespasian took the opportunity for more drastic changes that aimed at a break with their predecessors, the other Flavians had a double agenda. On the one hand, they used the variation in the contemporary iconographic pool for different concepts, well adapted to their situation within the family dynasty and depending on their relative distance in time to Nero. On the other hand, they followed the Augustan concept of a face with recognizable family features, connecting father and sons, thus symbolizing inner dynastic continuity (concordia) and foresight (providentia) with regard to their potential heirs. The strong Flavian family connection, displayed from the beginning on Vespasian’s coins up to Domitian’s family monuments, should be seen in contrast to Nero’s solitary rule. It can be understood as a strategic move: by forming a solid union against the former dynasty and ensuring a stable dynastic succession, they wanted to avoid a similar end. If we agree that there was a consensus between emperor and Senate concerning the creation of coin reverse motifs, the promotion of the principes iuventutes and the stable continuation of the Flavian rule must have been in the interest of the Roman elite, too.

For the other iconographic elements and dimensions of imperial images, which were chosen by the commissioner of the respective representation, a continuous and stepwise development can be observed. In this paper, those developments, observed in different medial contexts, were exemplified with regard to the godlike iconography and divine attributes as well as colossal dimensions. We saw that nearly all the iconographic novelties and their semantic aspects comparing the emperor to specific gods were included in the successors’ representation. Apparently, there was no impulse to move backwards to a more traditional level, not even after the death of a condemned emperor like Nero. This is even more signif icant considering the fact that a great amount of these changes occurred in a seamless transition from Nero to Vespasian in official imperial coinage, acknowledged by the new emperor and the Roman Senate. The Sol colossus is no official monument, but it surely had an impact on what was considered achievable in Rome. It coincides not only with the introduction of divine elements for the living emperor in imperial coinage but also with the beginning increase of larger-than-life-size images under the Flavians in Rome, climaxing during Domitian’s reign. Of these monuments, the equus Domitiani, although destroyed after his damnatio memoriae, illustrates again how certain image elements could become part of the successor’s representation – depending on a suitable choice of location for Trajan’s equestrian monument. The continuation or introduction of specific honorary elements in official public images, treating the princeps no longer as primus inter pares but elevating him to a higher rank, suggests a wider acceptance by the senatorial class of the elevated position of the imperial family, as well as of the dynastic principle.

Contrary to literary tradition, reactions to Nero’s Rome in the archaeological record of visual representation do not completely reject previous developments, but are multifaceted. The Flavians had different strategies to cope with their predecessor’s images and they used their concept of the portrait head to make statements against his rule, and also to support the consolidation of their family. The various image honours attributed to the emperor by the Senate and other commissioners showed instead an astonishing continuity, even for those newly introduced, more precarious elements like the aegis, etc. With regard to imperial representation, these observations underline not only the involvement of different parties, but also the fact that the image-making process is not static or unilateral, but rather flexible and elastic, thus an explanation for iconographical extensions, breaks, and continuity.126

After Nero, Vespasian and his sons succeeded in establishing a new dynasty, reflecting the importance of the family connection not only in their portraits but also in other official images, mainly on coins. Despite the more nonconformist or even transgressive iconography that can be noticed in Nero’s images, most of these transgressive elements are integrated step by step into the imperial representation of the Flavians – and even extended under Domitian. These developments in visual representation illustrate an increasing acceptance of the elevated position of the princeps and the dynastic principle, thus revealing a revision of the original idea of the principate.127

Appendix

Endnotes

- The essential historiographic evidence by Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, i.e. the main ancient biographies of Nero, is collected by Hurley (2013). For the literary evidence on the Flavians, see Hurlet (2016). For different explanations leading to the negative image of Nero, see Bergmann (2013) 353–358; Flaig (2014) 273–358.

- Witschel (2006); Winterling (2007). Winterling (2003) 115–118, 175–180 discusses these mechanics for Caligula. See also the articles in Winterling (2011) dealing with changes in the historiography of the last centuries, distancing themselves from the seemingly pathological doings of the emperors, evoked by the ancient authors, and assuming instead a specific strategy behind these mentions.

- For these mechanics, see Schulz in this volume; Schulz (2014) on alternated causal relations in Cassius Dio; cf. Cordes (2017) on the negative conversion of certain codes (recoding) in panegyric literature.

- On representation and different media, see Weber and Zimmermann (2003), especially with the contributions of Niquet (epigraphy) and Wolters (numismatics).

- Fronto, Ep. ad M. Caes. 4.12.4: in omnibus argentariis mensulis pergulis tabernis protectis vestibulis fenestris usquequaque ubique imagines vestrae sint volgo propositae (‘in all money-changer’s bureaus, booths, bookstalls, eaves, porches, windows, any where and every where there are likenesses of you exposed to view’). On the settings and contexts for imperial portraits, see Fejfer (2008) 373–429.

- Schneider (2003) 59–63; Bergmann (2009) 166–173; von den Hoff (2011) 15.

- See Schulz in this volume. Cf. Nauta (2014) on the categorization as malus/pessimus princeps and bonus/optimus princeps; in contrast to Nero or Domitian, see, for example, Suet. Tit. 1.1 with the characterization of Titus as amor ac deliciae generis humani (‘delight and darling of the human race’).

- For the understanding of the relationship between prototype and replicas, see the graphic in Boschung (1989) 31.

- On the creation of the portrait concept: Zanker (1990) 103–104; Brilliant (1991) 7–21; Lahusen (1997) 76–90; Schneider (2003) 59–63, 74–75.

- On the relation of coin portrait and sculptured portrait, see lately Beckmann (2014) 39–50; on the copying process of three-dimensional portraits, see Pfanner (1989) 157–158, 219–220, 176–204. On production and dissemination, see Fejfer (2008) 404–425; on methodical questions, see Fittschen (2010).

- Zanker (1990) 104–106; von den Hoff (2011) 20–22. On the different iconographic choices, see Lahusen (2010) 27–46. Cf. SHA Opilius Macrinus 6.8 on iconographically differentiated honorary statues for Septimius Severus and Caracalla.

- See Fejfer (2008) 181–261, 393–404, 439–445; Koortbojian (2008); on iconographic codes and their semantics: Hölscher (2009).

- The honorary function of the images is described by Dio Chrys. 31.149; Plin. Pan. 55.6–8. See also Zanker (1979) 359–360; Lahusen (1983) 129–143.

- Bergmann (1998) 91–92 and Bergmann (2006) 144–146 observes the necessary distinction between images as self-representation and those attributed as honours, especially in case of divine or extraordinary themes. See also von den Hoff (2011) 17–20.

- Cf. Zanker (1990) 46–50, 103–106; Fejfer (2008) 389; von den Hoff (2011) 15–26.

- Cf. Witschel (2006) 124; von den Hoff (2009) 260–261 discussing the situation dealing with certain iconographic elements after Caligula.

- Wolters (2016) 95–96; for a more detailed study: Wolters (1995) 290–308; see also Bergmann (1998) 91–98.

- Damnatio memoriae is a modern expression for the ‘eradication of the memory’. See the archaeological studies on this ancient phenomenon: Bergmann and Zanker (1981); Varner (2004).

- Nero declared as public enemy: Suet. Ner. 23.1; 49.2; see Flower (2006) 196–271. For the relevant archaeological material, see Bergmann and Zanker (1981); Varner (2004) 46–85, 237–256.

- Plin. Pan. 52.4–5; Suet. Dom. 23.1.

- Cf., for example, Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 407–409 no. 47 fig. 64a-c.

- See Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 335–410; Varner (2004) 52–61, 240–254.

- For the three affected portrait types of Domitian, see below p. 258-259; on the reworking patterns: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 349–360, who show, for example, that Nero’s uncommonly long hair at the neck was always obliterated.

- On the technical and sculptural compromises, pointing to a reworked portrait: Kovacs (2014) 25–29; cf. Fittschen (2012) 640–643 for a critical approach, asking for explicit remains of the former portrait.

- This is made clear by a passage in Fronto, Ep. ad M. Caes. 4.12.4, commenting not only on the omnipresent but also often badly worked copies of the emperor’s portrait. Nonetheless, Fronto feels animated to smile. That people were aware of those imperfections becomes clear from Arr. Peripl. M. Eux. 1.2–4, who sends for a new statue as substitution for an old one that did not resemble the emperor. The archaeological record provides us with such an unsatisfactory result, namely a portrait of Nero reworked subsequently into Domitian and then into Nerva: Varner (2004) 58, 117, 251 cat. 2.50, 263 cat. 5.13 fig. 61a-e.

- Cf. Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 379–380 no. 28 fig. 47a-d for a former portrait of Domitian remodelled into an excellent replica of Titus’s accession type, but still bearing undeniable traces of Domitian’s characteristic back hair.

- Varner (2004) 4, 9.

- Cf. Bergmann (2013) 339–340 for the observation that the portraits of young Nero, seen at that time as a new hope, had a better chance to survive than those from his late years.

- Cf. Meier (2010) esp. 9–40, on different ways of coping with the past and the problem of forgetting.

- Cf. Nero’s portrait type ‘Cagliari’ with main replica in Cagliari, Museo Archeologico Nationale, inv. no. 35.533. On Nero’s early portrait types, see Boschung (2016) 82–84 f igs. 1–2; lately Bergmann (2013) 332–335 figs. 20.1, 20.2. For a first typological analysis of Nero’s portraits, see Hiesinger (1975) esp. pl. 17–18 with an overview on the development of the coin obverse portrait.

- For the Augustan portrait model, see Zanker (1979) 361–362; Zanker (1990) 103–106; see also Boschung (2002) on the image of the gens Augusta.

- On this break, see Schneider (2003) 63–68.

- Portrait type ‘Thermenmuseum’. Cf. the main replica in Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, inv. no. 618. On the portrait type: Bergmann (2013) 336 f ig. 20.6; Boschung (2016) 84–85 figs. 3–4. For the coin obverse portraits: Wolters (2016) 91 fig. 6.

- Portrait type München-Worcester. Cf. the main replica in Munich, Glyptothek, inv. no. 321. On the portrait type; Bergmann (2013) 336–337; Boschung (2016) 85–87 fig. 5; Wolters (2016) figs. 13–14.

- Convincingly: Bergmann (2013) 336–337.

- Suet. Ner. 51.

- For a first collection of the ancient sources and the discussion of the negative connotation, see Cain (1993) 88–92; recently: Bergmann (2013) 337–339.

- See Cain (1993) 84–89 tracing the motif of the luxurious coiffures back to its origins for a better understanding of its semantics; on p. 68 she observes that until the time of Hadrian the focus for the wearing of these coiffures lay on young men.

- For an elaborate and instructive overview on developing iconographic and stylistic variety in male portraiture in the second half of the first century CE, see Cain (1993). These temporary prevailing trends can be described as ‘period face’ (‘Zeitgesicht’; Zanker [1982]) and serve the iconography of imperial as well as private portraits, exerting a mutual influence and thus resulting sometimes in very similar appearances: Fittschen (2010) 236–241; on the difference to ‘imitative private portraiture’ with intended assimilation to the imperial portrait; see also Bergmann (1982).

- Cain (1993) 91–95, especially p. 94 with the citation of a passage by Artem. 1.22 on the rare positive reception.

- On this change of lifestyle and the contextualization of Nero’s Rome, see Bergmann (1994) 27–30; Bergmann (2013) 335–358.

- Bergmann (2013) 339 considers the fat face as the predominating element, so that the intended message of his portraits must have been pleasure and ‘not the production of abstract beauty’.

- Cain (1993) 100–104; Bergmann (2013) 338–339; on literary depictions of Nero’s youth, see the contribution of Cordes in this volume, especially the second section.

- Portraits of Galba, Otho, and Vitellius are known mainly from coin obverses: RIC II.1 263, 322, 340 (Galba); 3, 16, 18 (Otho); 121, 130, 136, 169 (Vitellius). On their portrait concepts, see Schneider (2003) 69–70.

- On Vespasian’s counter-image, see Schneider (2003) 70–74. See also Zanker (1979) 362–363, underlining the contrast to Augustus and his successors.

- Main type with best replica in Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, inv. no. 2585; on this main type, see Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 332–349 fig. 12a-c, while fig. 13a-c (Sevilla, Museo Arqueológico, without inv. no.) represents another rarer type with reduced ageing signs. The current assumption that the more idealized type followed the ageing type is challenged by Rosso (2010) 178–182, suggesting that the younger and more dynamic image was created in Alexandria and converted only in Rome to a more traditional appearance. On coin obverses this dominates from early on the older version: cf. RIC II.1 32, 49.

- The baldness and wrinkles are signs of old men and their experience (Cain [1993] 95–96), not necessarily relating to republican images (Zanker [1979] 362–363). Schneider (2003) 72 with the characterization as ‘bürgernah’, i.e. a man of the people.

- Schneider (2003) 59.

- At Vespasian’s accession, Titus (*39 CE) must have been 32 and Domitian (*51 CE) 20 years old (cf. Kienast [2011] 111, 115). For the visual representation of Titus and Domitian, see my PhD thesis (Wolsfeld [2021]). The catalogue lists as far as possible all known portraits, as a basis for a complete revision of typology, and the analysis of the iconography of their images. Medial categories allow a more differentiated look with regard to the historical background and the functioning of the representative system.

- Type ‘Neapel-Vatikan’. See the main replica from Herculaneum in Naples, Museo Nazionale, inv. no. 6059. On the type, see Daltrop et al. (1966) 18–29 pl. 10. 16d; Fittschen (1977) 64–65. Exemplary for coin obverses showing the type from 71–79 CE: RIC II.1 611 (Vespasian).

- See above pp. 252-254.

- Cf. Boschung (2002) no. 5.3 pl. 27 no. 12.2–12.3 pl. 38.3–4, and no. 27.2 pl. 76.2.

- Type ‘Thermenmuseum-Stuttgart’. See main replica in Rome, Museo Nazionale, Palazzo Massimo alle terme, inv. no. 226. This main pre-accession portrait type has come down on us with a majority of copies: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 349–360 with fig. 25a-d. By now there is evidence for two other early portrait types, with fewer replicas, related to the main type through comparable front hair motifs: Type ‘Boston-Rom’: see replica in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. no. 88.639; Fittschen (2006) 158–159 n. 1; cf. Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 356–359 fig. 30–31, listing them as simple variations of the main type. Type ‘Braccio Nuovo-Montemartini’: see replica in Rome, Centrale Montemartini, inv. no. 859; Fittschen and Zanker (2014) 50–51 no. 46 pl. 65. These three types correspond with coin types from 71–72 to 76–77 CE: cf. RIC II.1 492, 926 (Vespasian). Another independent type, also presumably pre-accession, can be discerned, already with a more elaborate hairstyle: Type ‘Neapel’: see replicas in Naples, Museo Nazionale, inv. nos. 6058 and 150–216: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 360–363 f igs. 33 and 35. This type can be associated with coin portraits from 77–81 CE: RIC II.1 330 (Titus).

- As noted above, nearly all the replicas of Domitian’s early portrait types are reworked from portraits of Nero: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 350. On literary praise and critics on Domitian’s youth, see the contribution of Cordes, especially the third section, in this volume.

- Cf. Zanker (1990) 107–170 with Augustus turning to civil representation after Actium.

- See Cain (1993) 70–74 on the so-called coma in anulos (‘hair arranged in ringlets’).

- Type ‘Erbach-Pantelleria’. See main replica in Pantelleria, Castello, without inv. no. 5857; see Schäfer (2004) 31–35 figs. 22–26; see also Fittschen (1977) 64–65 pl. 23 with the other main replica in Erbach, Castle, without inv. no.; cf. coin portraits from 79 CE on: RIC II.1 153.

- Type ‘Conservatori 2451–1156’. See main replica in Rome, Palazzo dei Conservatori, inv. no. 1156; Fittschen and Zanker (1985) no. 32 pl. 34, 36 and no. 33 pl. 35, 37 (other main replica); cf. coin portraits from 81–96 CE: RIC II.1 106. Despite their different appearances, the main replicas of Titus’s as well as Domitian’s portrait type must originally trace back to the same prototype, but they represent stylistic and fashionable counterparts (see footnotes below).

- Cf. Cain (1993) 60–61, observing that even among private portraits with hairs arranged in gradus technique, none of them imitates Nero’s coiffure exactly, but rather they come along in a more moderate fashion.

- Observed by Cain (1993) esp. 66–68. The arrangement and shape of hair strands should not be mistaken for contemporaneous stylistic changes, a problem which she discusses on pp. 38–57.

- For variations, especially of Domitian’s coiffure, compare the two main replicas in Fittschen and Zanker (1985) cat. 32 pl. 34, 36 and cat. 33 pl. 35, 37 as well as a third one with the face reworked to Nerva at the University of Leipzig, now lost: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 389 no. 31 fig. 52.

- In contrast to the portraits of Otho and his intended reference to Nero: Schneider (2003) 69–70.

- See above pp. 254-255.

- Cf. Zanker (1982) and Bergmann (1982) on the so-called ‘Zeitgesicht’; otherwise Zanker (2009) 64, assuming that Titus and Domitian were only fashionable with their portrait choice without the intention of a special message.

- More so if Nero’s self-stylization was ‘closely linked to a process of change within the Roman value system as a whole […] soon accepted by the wider public’ (Bergmann [2013] 339, 355–357).

- On the idea of an intended imitation, see below p. ## (18).

- See p.## (13) below.

- On the iconography of Nerva: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 380–388 f igs. 50–51; on Trajan: Gross (1940); see also Jucker (1984) 23–51.

- Except for a daughter, who died only three months after birth (Kienast [2011] 100); cf. Drinkwater (2013) 164, 168, who points out in his analysis on Nero’s ‘half-baked principate’ that the emperor failed to produce an heir.

- See also Wood (2016) 131–132, commenting especially on the resemblance of Vespasian and Titus.

- While Titus’s front hair is variated by a pincer motif over the left eye, Domitian’s front locks form a continuous line from the fork at the right corner of the forehead to the left temple. At the back of Titus’s portrait heads the strands originate from a cowlick around the middle, whereas for Domitian’s portraits they start from a lower point just over the neckline.

- Suet. Dom. 18.

- On the phenomenon of Julio-Claudian family resemblances, see Boschung (2002) 180–192; further Massner (1982) speaking of ‘Bildnisangleichung’ (image assimilation); see also Boschung (1993) with an overview on the family member’s portrait types; see Giuliani (1986) 180 for antique text passages underlining the importance of physiognomic likenesses to demonstrate the affiliation to a gens.

- See Boschung (1993) 52–54; on the assimilation phenomenon observed for Augustus’s heirs: Boschung (2002) 184–190. An alternative choice was made, for example, by Tiberius (Hertel [2013]), whereas Caligula sought a closer link: von den Hoff (2009) 243–244.

- Cf. Zanker (1990) 217–228.

- This is especially the case for the Julio-Claudian family groups: Boschung (2002). Flavian groups are less numerous (cf. Deppmeyer [2008] cat. 1–28, with the review by Fittschen [2009]), but there is, for example, a statue pair of Vespasian and Titus from Misenum (Muscettola [2000] 81–87 figs. 3–6).

- There is even evidence for some presumably posthumous portraits of Titus, which were adapted even closer to contemporaneous portraits of Domitian in hairstyle and facial features: cf. this assimilation between Titus’s portrait from Pantelleria (Schäfer [2004] 31–35 figs. 21–26) and Domitian’s portrait in Rome (Fittschen and Zanker [1985] pl. 37).

- Cf. the bronze portrait of Nero from Berlin, Collection Axel Guttmann: Born and Stemmer (1996) figs. 1 and 9.

- Cain (1993) 104–106.

- On the different characterizations of Vespasian and Nero, see Schneider (2003) 72. On Vespasian’s efforts to consolidate the empire, see Pfeiffer (2009) 20–32; Nicols (2016).

- From 71 CE onwards he held the tribunicia potestas, and shared several consulships with his father as well as the office of censor in 73–74 CE (Kienast [2011] 108–109, 111–112).

- On economics cf. Launaro (2016) 196–203.

- Cf. RIC II.1 62 (71 CE) with caduceus and cornucopia.

- Cf. RIC II.1 259 (71 CE) with corn ears, poppy, and sceptre.

- Cf. RIC II.1 876 (76 CE) with a sack of corn ears; cf. other unusual motifs indicating fecundity: RIC II.1 977–984 (77–78 CE): a goatherd milking a goat, a modius with corn ears, and a sow with three piglets.

- Titus: RIC II.1 55 (Annona), 136 (Annona, alternative motif ), 69 (Ceres), 141 (Felicitas). Domitian: RIC II.1 128 (Felicitas), 212 (Annona), 369 (Annona and Ceres), 245 (quadrantes: Ceres).

- Cf. Vespasian’s coinage, with key words like LIBERTAS RESTITUTA (RIC II.1 88), ROMA RESURGENS (RIC II.1 109) or PAX AUGUSTI (RIC II.1 380).

- Wolters and Ziegert (2014) 55–56, 59–60.

- On Titus’s and Domitian’s representation on imperial coins under Vespasian: Seelentag (2009) 88–100 figs. 1–9 (shared motifs).

- For mutual motifs, see, for example: RIC II.2 363 (for Vespasian). 368 (for Titus); on separate motifs for Titus: Seelentag (2009) 93–89 figs. 9–10. For Domitian’s riding type: e.g. RIC II.1 540.

- Cf. Seelentag (2009) 98–100 with fig. 7 on the spes augusta resting on both Caesares.

- Domitian’s biological son died young and is probably commemorated on a special coin reverse: RIC II.1 152–153 (Domitian). On the problem of the unsolved succession under Domitian, see Witschel (1997) 104–105.

- RIC II.1 159 (Titus), complemented by the legend PIETAS AUGUST, connecting brotherly concordia to pietas towards their family duties.

- On the divinization of family members under Domitian, see Rosso (2007) esp. 127–128; on the family monuments, see Coarelli (2009a) 75–77, 86–94; cf. the arch of Titus, erected also under Domitian as a consecration monument, but commissioned by the senate (Pfanner [1983] 98–99). On Flavian women and especially Domitian’s relations to women, see the contribution by Ambühl to this volume.

- Suet. Vesp. 23.4; Darwall-Smith (1996) 48–55. On the Flavian position to Nero’s divine predecessor and his legacy, see the contribution by Gallia in this volume.

- Wolters and Ziegert (2014) 52–53.

- See Bergmann (1998) 174–175 pl. 34.2–3. As she points out, the globe had already become a more common attribute, but appears under Nero together with aegis and radiate crown in official images of the living emperor.

- See the fundamental study by Bergmann (1998) 112–132 (semantics and sign of the Divi), 2 1 4 – 23 1 (Nero).

- For a concise overview: Bergmann (2013) 342–351; in detail: Bergmann (1998) 150–189. On Nero’s divine status as divi filius, cf. the contribution by Gallia in this volume.

- Aegis on Domitian’s coin obverse constantly from 84 (RIC II.1 207) to 95–96 CE (example: RIC II.1 800); see Bergmann (1998) 231–242 on the radiate crown under the Flavians. First time in combination in 85 CE: e.g. RIC II.1 289. See Wolters and Ziegert (2014) 61–62 on the standardization of these elements after Nero.

- See pp. ## (3–4) above.

- Essential contribution on the Sol colossus, the literary and archaeological evidence for its reconstruction and context: Bergmann (1994) 7–17; see also Ruck (2007) 194–197. On how the Flavians dealt with the remains of Nero’s Domus Aurea on the Palatine Hill, see the contribution of Raimondi Cominesi in this volume.

- See Bergmann (1994) 11–12 text f ig. 10 (reconstruction), mainly based on Gordian multipla reverses and a gem image in Berlin (pl. 2.1, 2.3).

- Bergmann (1994) 9–10: The association would of course have been stimulated by various image allusions to Sol from his reign. Bergmann (2013) 349–350; see also Varner (2004) 66–67; cf. Smith (2000) 536–537, relativizing the identification.

- Cf. its later fate with a relocation under Hadrian, the remodelling into Commodus-Hercules and finally the change back to an image of Sol: Bergmann (1994) 10–11.

- See Cancik (1990); Stemmer (1971) 578–579 on colossal dimensions as part of a Flavian stylistic sense.

- On the evidence, see Ruck (2007) 58–59, 215. Cf. Suet. Vesp. 23.3: Vespasian declined an offer for the erection of a colossal statue by opening his hand with the comment that the base (for the value in coins) is ready.

- There are also Domitianic colossal portraits of Titus from Rome and its close surroundings: Daltrop et al. (1966) 87 pl. 21a-b (probably from Ostia), 94–95 pl. 15a; Ruck (2007) 117–118 (quadriga, arch of Titus), 216, 280 cat. 6; Coarelli (2009b) 442 cat. 33 (fragment).

- Apart from the equus maximus there are two more headless colossi in Rome that can be attributed to Domitian: see Ruck (2007) 172–173, 198–199 cat. 7 pl. 15.3–4 (fragment of cuirassed statue) and 89, 280 cat. 8 pl. 16.1–3 (‘Pompeius Spada’). Additionally, Mart. 8.69 reports a Palatinus colossus, which could be associated with the cuirass fragment found on the Palatine.

- Stat. Silv. 1.1. A coin reverse image from 95–96 CE (RIC II.1. 797) can be associated with Statius’s description and helps to reconstruct the monument’s iconography. See Bergemann (2008) 16, 26–29 fig. 14 and 164 Kat. L31. On the date of erection; Coarelli (2009a) 80–83 fig. 17–21.

- Stat. Silv. 1.1.99 (commissioned by SPQR); following Bergemann (1990) 42, it is very likely that the monument was influenced by Domitian; Klodt (1998) 23 even thinks of Domitian as the main agent in the planning process.

- See Zanker (1990) 46–52 with figs. 29–32 on his outstanding public honorary statues.

- With the increasing appearance of the completely naked statue types, featuring a greater attributive variety and a potential military connotation, the previously preferred hip mantle statues declined in number, obviously having become less appreciated by the commissioners. See Hallett (2005) 160–183; see also Post (2004) 370–371.

- Cf. an exceptional motif on Nero’s coin reverses presenting him and his wife in a theomorphic manner: Bergmann (1998) 178–179. Rare exceptions are known from eastern mints, for example, RPC II 1924 (= RIC II.1 1550, Antiochia) alternating a common type of PAX AUGUSTI by the naked, Jupiter-like figure of Vespasian.

- In 85 CE, a new coin reverse motif (e.g. RIC II.1 640) was introduced as part of a victory set: see Wolters and Ziegert (2014) 62 f ig. 21. Domitian appears in military dress, crowned by Victoria and holding the thunderbolt as a sign of his Jupiter-like status. This motif, comparing emperor and Jupiter in a public medium, is repeated in the exact same way for Trajan: Woytek (2 01 2) 320-321.

- On the iconography of the monument: Bergemann (1990) 164–166 cat. L31.

- Cf. the similar attire of Marcus Aurelius’ equestrian statue: Bergemann [1990] 105–108 cat. P51 pl. 78.

- On the Augustales in context, see Wohlmayr (2004) 49–57; Fejfer (2008) 73–89. They can be described as a semi-official association, inaugurated by the cities for taking care of the imperial cult. Although they were open to the public, representational conventions in the compound were surely less restrictive than on the Forum Romanum.

- See Muscettola (1987) 39–66 pl. 1–8.; on the iconographical extraordinariness: Bergemann (1990) 82–86 cat. P31 pl. 56–58; on the reworking: Bergmann and Zanker (1981) 403 no. 41.

- The only remnant is maybe a rectangular irregularity in the paving in the Forum’s middle: Coarelli (2009a) 81–90.

- On the equus Traiani, see Bergemann (1990) 42, 166 cat. L32 pl. 92h (= RIC II 291, 598). Cf. Ruck (2007) 107–109 on the choice of location.

- Herod. 2.9.5–6; Bergemann (1990) 166–167 cat. L34.

- The riding type as well as the Roman clothes are not compatible with divine imagery, whereas the Sol colossus’ appearance was derived completely from divine iconography.

- Cf. Bönisch-Meyer and Witschel (2014) 148–155 (inscriptions); Beste and Filippi (2016) 196–198 (Domus Aurea).

- Cf. von den Hoff (2011) 26–31 with a concise overview, showing that in fact innovations and changes are very common to imperial portraits from Augustus to the third century CE.

- Cf. von den Hoff (2009) on Caligula, underlining that these developments (iconographical extensions, breaks, and continuity) become even clearer for rulers with a more untraditional image.

- Cf. Sion-Jenkins (2000) 19–64 on the contemporaries’ increasing awareness of the change of the political system. Cf. also discussions on the role of Domitian’s rule for a monarchical evolution of the principate: Strobel (1994) 359–374; Witschel (1997) 106–108. I would like to thank especially Ralf von den Hoff, Alexander Heinemann, Lisa Cordes, Martin Kovacs, and Marianne Bergmann for their unfailing readiness to discuss Nero and Domitian on various topics and their expertly support in all matters of Roman imperial representation.

Bibliography

- Barbanera, M. & Freccero, A. (Eds.) (2008). Collezione di antichità di Palazzo Lancellotti ai Coronari. Rome.

- Beckmann, M. (2014). The Relationship between Numismatic Portraits and Marble Busts: The Problematic Example of Faustina the Younger. In Elkins, N. T. & Krmnicek, S. (Eds.) ‘Art in the Round’: New Approaches to Ancient Coin Iconography (pp. 39–50). Marie Leidorf.

- Bergemann, J. (1990). Römische Reiterstatuen. Ehrendenkmäler im öffentlichen Bereich. Zabern.

- Bergemann, J. (2008). Virtus. Antike Reiterstatuen als politische und gesells-chaftliche Monumente. In Poeschke, J., Weigel. T. & Kusch-Arnhold, B. (Eds.) Praemium Virtutis III. Reiterstandbilder von der Antike bis zum Klassizismus (pp. 13–30). Rhema.

- Bergmann, M. (1982). Zeittypen im Kaiserporträt? Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 31, 143–147.

- Bergmann, M. (1994). Der Koloss Neros, die Domus Aurea und der Mentalitätswandel im Rom der frühen Kaiserzeit. Trierer Winckelmannsprogramme, 13, 1–37.

- Bergmann, M. (1998). Die Strahlen der Herrscher. Theomorphes Herrscherbild und politische Symbolik im Hellenismus und in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Zabern.

- Bergmann, M. (2006). Konstantin und der Sonnengott. Die Aussagen der Bildzeugnisse. In Demandt, A. & Engelmann, J. (Eds.) Konstantin der Große. Geschichte – Archäologie – Rezeption. Internationales Kolloquium vom 10.–15. Oktober 2015 an der Universtität Trier zur Landesausstellung Rheinland-Pfalz 2007 ‘Konstantin der Große’ (pp. 143–161). De Gruyter.

- Bergmann, M. (2009). Repräsentation. In Borbein, A. H., Hölscher, T. & Zanker, P. (E d s .) Klassische Archäologie. Eine Einführung (pp. 166–188). Reimer.

- Bergmann, M. (2013). Portraits of an Emperor – Nero, the Sun, and Roman Otium. In Buckley, E. & Dinter, M. T. (Eds.) A Companion to the Neronian Age (pp. 332–361). Wiley Blackwell.