Electricity won popular praise as a new technology that would revolutionize home and industrial life.

Edison and the First Power Station

The modern electric utility industry in the United States can be traced to the invention of the practical light bulb in 1879 by Thomas Alva Edison. Always looking toward the marketplace, Edison realized that his light bulb would mean nothing unless he developed an entire electric power system that generated and distributed electricity.

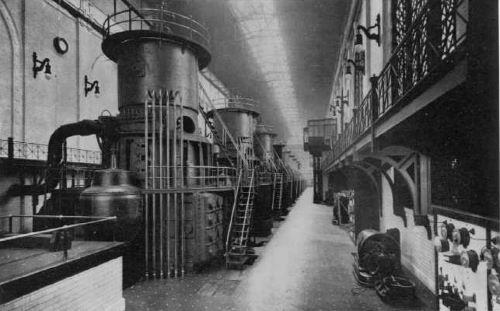

By 1882, he had developed such a system, and he installed the world’s first central generating plant on Pearl Street in New York City’s financial district. Reciprocating steam engines provided the motive power to generators, which produced direct-current (DC) electricity to shop owners and other businesses that used electric lighting as a novelty to attract customers.

But soon after introduction of central station power, Edison and others introduced appliances that made electricity more versatile and valuable. Electric motors found use in fans and as replacements for bigger, more expensive, and more difficult-to-maintain steam engines in factories; electric irons quickly became a best seller for home-use, substituting for the heavy and cumbersome irons that needed frequent reheating on coal or wood stoves. Cities such as New York quickly introduced electrically operated street cars, which could be controlled more easily and operated more cheaply than their horse-drawn counterparts.

Early Competition

Electricity won popular praise as a new technology that would revolutionize home and industrial life. As entrepreneurs saw a large market for electricity consumption, they sought franchises from municipal governments to build power stations that would dot city landscapes. In many cities, numerous companies produced power for customers, because the power plants of the time were limited by the technological constraint inherent in direct current transmission.

Produced and distributed at relatively low voltages–around 110 volts–direct current electricity weakened substantially as it traversed the copper distribution lines. In practice, customers needed to be within one mile of a generating plant to receive power. As a result, the emerging paradigm of electric power production appeared to consist of cities being populated by numerous power plants, each selling to customers within a small radius. Typically, the large investment required for the plant prohibited one company from owning all of them. But the firms often tried to win lucrative customers in the others’ turfs.

Samuel Insull and Chicago Edison

When Samuel Insull arrived in Chicago in 1892, the town hosted more than twenty companies producing electricity. The British-born secretary of Thomas Edison, Insull assumed the presidency of the small Chicago Edison company, one of many Edison franchises around the country. Because of his work in Chicago, Insull is remembered for his many managerial and technological innovations that transformed the utility system into its modern structure.

Quickly learning at his new job, Insull realized that his company could make more money by increasing what became known as the “load factor”–the ratio of average daily or annual power use to the maximum load sustained during the same period. Since Insull needed to purchase equipment to meet the peak load of use during a day–typically in the evening when customers used electric lights–he was stuck with power generating technology that sat idle most of the rest of the day. But Insull understood that if he could find customers who would use electricity during off-peak times, he could increase his company’s income while avoiding new capital purchases (though he would still incur marginal expenses related to increased fuel use). Those customers existed, though many generated power for themselves. By enticing customers such as street railway companies, ice houses, and other businesses with low rates for off-peak power usage, Insull increased his load factor dramatically. He also found that lower-cost power stimulated demand, while still earning healthy profits for his company.

Samuel Insull and Economies of Scale with Steam Turbines

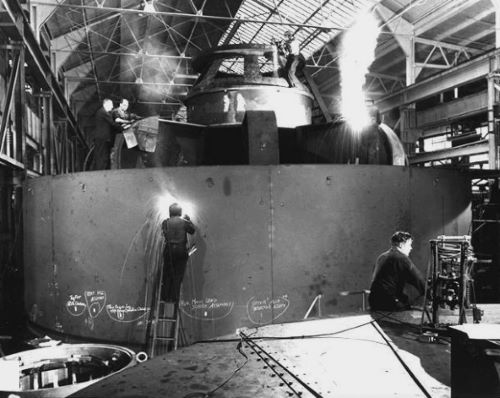

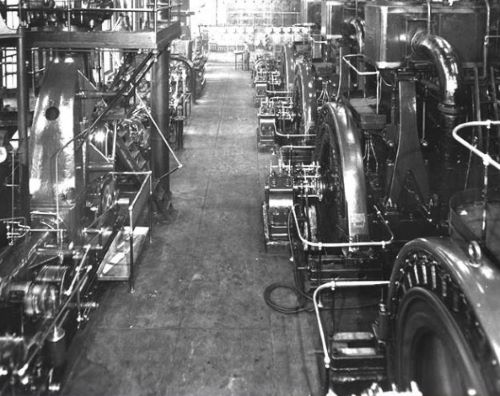

Insull also realized how to exploit new technologies. For example, during the late 1880s and 1890s, a few power companies in Europe began using a steam turbine to power generators instead of reciprocating steam engines. Large, bulky, noisy, and hard to maintain, the reciprocating engines of the day converted up-and-down motion to rotary motion for use by electric generators through the use of a large flywheel. But by the end of the 19th century, these behemoths were reaching limits to their productive capacity. The new steam turbines, invented by Englishman Charles Parsons in 1884, on the other hand, produced rotary motion directly, as steam passed through vanes on a long shaft. Much smaller in size, simpler mechanically, and more quiet than reciprocating engines, steam turbines produced a great amount of power from a small package. More importantly, the turbines could be scaled up to produce even more power with proportionally less investment in material. In other words, the steam turbine exhibited great “economies of scale” such that larger units produced electricity at lower unit cost.

Taking a great risk at the time, Insull ordered a turbine-generator set from the General Electric company in 1903 that produced 5,000 kilowatts (kW) of power (5 megawatts [MW]). Pleased with the unit’s performance, he ordered other turbines that generated 12 MW in 1911. Power costs plummeted, allowing the company to sell more electricity at still lower rates.

Using steam turbines would not have been a successful strategy had it not been for Insull’s use of an associated new technology–alternating current (AC) transformers. Developed in the 1880s, AC transformers overcame the technical limitation of transmitting low-voltage direct-current to distances beyond one mile. When power produced with already existing AC generators was transformed up to high voltages, current could flow for many miles without significant degradation. In 1896, for example, Edison competitor Westinghouse Electric built a system of water-turbine generators at Niagara Falls that produced power for transmission to Buffalo, 20 miles away. The AC power illuminated lights, just like direct current, and it powered the new AC motors that recently came to market. Since it could do everything direct current could do–with the important plus that it could be transmitted long distances–AC quickly won the day, leading to the demise of Edison’s direct current systems.

Consolidation

Insull quickly realized that competition in the electric power supply business would never allow him to exploit the scalable turbine-generators and AC transmission systems. After all, if many companies divided the market for electricity, none would have the demand for power that could be met by the bigger turbine-generators. To remedy the problem, Insull sought to consolidate his company with others. After buying the firms, he often turned their generating stations into substations, relegating the generating equipment to back-up spares, and he used large, efficient steam-turbines to produce power for all customers. He also sought new customers, even some rural customers outside the city limits, to help him diversify the company’s usage patterns and increase the load factor.

Successful in his efforts, Insull acquired 20 other utility companies by 1907 and renamed the firm “Commonwealth Edison.” By that time, the company had already become known as one of the most progressive–and lowest cost–utilities in the world. As a result, Insull’s strategies became emulated by utility entrepreneurs in other cities throughout the United States.

Seeds of Regulation: Railroads and Electric Utilities

As successful as Insull’s company may have been, it was not universally loved. A virtual monopoly in Chicago, the company reminded many public-spirited politicians and individuals of other monopolies that rubbed people the wrong way, with railroads being the most notorious. Becoming the life blood of American commerce, the railroad industry by the 1870s had become effective monopolies within their markets, after enduring a period of heated and destructive competition. In several cases, railroad companies spent lavishly to lay down duplicate rail lines between lucrative markets and invested heavily in engines, cars, and other equipment, only to find that they could not make sufficient profits because of intense price competition.

Eventually, railroad owners realized that merging operations with competitors allowed them to increase rates and make more money. Attempting to eliminate monopoly abuses of the railroad companies, several state legislatures and the federal Congress passed legislation for creation of bodies that would regulate rates. Unfortunately for railroad customers, most of these regulatory bodies proved ineffectual.

Notion of “Natural Monopoly”

Regulation gained a more substantial foundation during a period of political agitation known as the Progressive era, which lasted from around 1896 through World War I. At the heart of regulation was the acceptance of the notion that some industries, such as the railroad business, constituted “natural monopolies.” According to academic economists, such businesses exhibited tremendous economies of scale or the necessity of huge capital investment (and usually both) such that only one company would dominate a market. In the railroad business, the large investment in equipment meant that duplication of facilities would incur great waste of financial and material resources, thus leading to overall higher costs for companies and higher prices to customers. Thus, monopoly appeared to be the natural outcome of such a situation, where one company could minimize the waste of resources to serve customers. In short, the railroad business was a “natural monopoly,” one in which big technology and the high cost of investment led companies to move to a non-competitive environment.

The situation seemed similar to what was occurring in the electric utility business. As electric power firms consolidated with others to exploit the benefits of large-scale turbine-generators and alternating current transmission, they increasingly looked like the epitome of natural monopolies. They were joined by other “public utilities,” such as water and transportation industries that constituted, according to Richard T. Ely, an economist writing in 1903, “monopolies because, we know from experience, we cannot have in their case effective and permanent competition.”

Models for Regulation during the Progress Era

Municipal Ownership

The big question for progressive reformers was how to gain for society the benefits of natural monopoly without suffering the abuses common among monopolist owners? The answer actually took two forms–municipal ownership and state regulation of companies. By purchasing firms providing essential services and commodities, cities could ensure that the benefits of natural monopoly would flow directly to the people (or so it was hoped). In the electricity supply business, customers would enjoy lower rates as the city-owned utility exploited economies of scale and increased sales to greater numbers of people and businesses. Since cities have no stockholders demanding dividend payments or returns on investment, they could pass on savings directly to their citizens.

State Regulation

While municipalization of electric utilities enjoyed growing popularity, they did not win universal approval. Progressive reformers, for example, had been strident opponents of corrupt city governments. Why should political officials all of the sudden gain enlightened management skills when operating power systems when they so blatantly stole from the public coffers in so many other situations? And in attempts to maintain low prices, for political reasons, managers might neglect maintenance, refrain from necessary investment in capital equipment, and offer low salaries that would discourage hiring of superior engineers and staff. Moreover, several critics of municipal systems viewed them as attempts to socialize American industry at a time when private enterprise still carried much popularity in society–the existence of abusive monopolies notwithstanding.

As an alternative, many progressives looked to state regulation. Though several states had created regulatory bodies to oversee the activities of railroad companies–with Massachusetts’ railroad commission created in 1869 being one of the most notable–few had the power to enforce their recommendations nor could they establish rates and fares. But the new type of regulation, promoted by progressive Republican governors in Wisconsin and New York in the first few years of the 20th century, was different. In 1905, for example, Wisconsin’s Governor Robert La Follette pushed through creation of a railroad commission that had full jurisdiction over a railroad’s rates, schedules, service, and operations of the state’s transportation companies.

Two years later, in July 1907, the Wisconsin legislature extended regulation to the state’s electric companies. The commission used its powers to compel utilities to develop standard accounting techniques, and it had the right to investigate companies’ books as part of the process for determining rates based on the physical valuation of a company’s properties. Just a month earlier, New York governor Charles Evan Hughes, signed into law a similar measure to create a regulatory body for the Empire State. Though the Wisconsin statute proved more sweeping in several respects, both states deservedly take credit for initiating the idea of state regulation of electric utilities. Gaining support from politicians and civic reform groups, state regulation of utilities became commonplace, such that by 1914, 43 more states followed the example of New York and Wisconsin by establishing government oversight of electric utilities.

Despite the move toward state regulation, the idea that city-owned utilities could better derive the benefits of natural monopolies for their citizens continued to hold some appeal. In fact, the number of municipal utilities peaked in 1922, with more than 2,500 “munis” in existence. Only accounting for about 5% of the nation’s total generating capacity and less than 4% of the total electrical energy produced, municipal ownership has remained a fixture on the utility landscape, even into the 1990s.

Roles of Regulation

The overall purpose of regulation, as viewed by its founders, was to serve as a body that would enforce the responsibilities and rights of electric power companies and their customers. For example, utility companies were required to serve all customers without discrimination who sought to buy power. To fulfil this “obligation to serve,” they would need to raise capital and build plants to meet projected loads. Moreover, utilities could charge customers “reasonable” rates for service–rates based on the value of their investments in equipment plus a fair rate of return on the so-called “rate base”–and they must do their best to provide service with as few interruptions as possible.

But utility companies earned valuable rights as part of the political consensus that created regulation. Perhaps most importantly, regulatory bodies legitimated the utilities’ status as natural monopolies within their service territories and protected them from interlopers. Utilities also earned the right of eminent domain, formerly a power reserved by the state, so it could obtain property for their generating plants, transmission towers, and other equipment that was necessary for supplying an increasingly necessary commodity.

Utility customers, on the other hand, undertook the responsibility, overseen by regulators, to pay rates that helped maintain the financial integrity of utility companies. Unlike politicians in municipal systems that might reduce rates to curry favor among voters, regulators would insist (in theory) that rates be sufficiently high to keep utilities financially healthy. Sometimes, this obligation meant that customers had to pay higher rates than in previous periods.

Benefits of Regulation to Utility Companies

Astute utility managers such as Samuel Insull anticipated the benefits of regulation to power companies. As early as 1898, he pointed out that regulation would legitimate the monopoly status of utility companies and would keep at bay those who harbored distrust and antipathy for non-competitive industries. In other words, regulation gave the utility industry a special place in the American political economy and protected it from those who saw evil in the big oil and railroad trusts of the day.

On a practical level, regulation allowed utility companies to raise money more easily, in the form of stock and bonds, than before the imposition of regulation. Since investors knew that regulators oversaw the financial accounts of utilities–in an era before public disclosure of accounts was made obligatory–they could feel that their investments in utility company securities was not as speculative as those in unregulated companies. Hence, utility companies could pay lower interest rates than more risky investments. Meanwhile, regulators helped guaranty the financial integrity of companies, meaning that utility bonds paid interest at regular intervals, and that utility stocks paid healthy-enough dividends to attract investment in what became the most capital-intensive industry in the United States. Without a doubt, utility stocks and bonds only became securities for the “widows and orphans” after regulation helped ensure their safe and secure status.

Expansion of 1910s and 1920s

During the two decades after regulation appeared, utility companies expanded to provide increasing amounts of electricity, at lower unit cost, to a greater number of customers. The electrical output from utility companies exploded from 5.9 million kWh in 1907 to 75.4 million kWh in 1927. In that same period, the real price of electricity declined 55%.

Holding Companies

Background

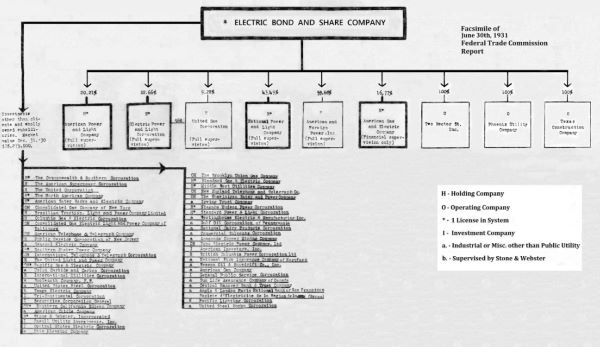

To help finance the great expansion, the utility industry exploited a financial innovation known as the “holding company.” Begun by equipment manufacturers, this type of company started by accepting the relatively unattractive stock and bond issues of utilities in exchange for generating and associated equipment. Thus, nascent utilities could therefore retain cash for their operations. After accepting the securities from several utilities (known as “operating companies”), the holding company issued stock and bonds using the subsidiaries’ securities as collateral. Investors preferred the securities offered by the holding company, because they provided diversification and more secure returns than did offerings from individual companies. A favorite holding company investment among many was the Electric Bond and Share Company, created by the General Electric company in 1905, to market the securities it acquired while selling equipment to utilities.

Because the holding company now had a stake in the operating companies, they offered management and engineering services that the smaller firms could not have afforded themselves. Moreover, the holding company often consolidated the equipment and management of smaller companies into larger ones, and it helped them interconnect transmission facilities to ensure higher levels of reliability. Overall, the holding company innovation appeared to facilitate expansion of the utility industry.

Abuse of Holding Companies

During the go-go years of the 1920s, however, some of the beneficial principles of the holding company concept got lost in the desire to exploit its business structure. Holding firms assessed high fees for arranging financing for their operating companies, and they provided engineering services at levels way beyond their cost. Meanwhile, the companies pyramided one sub-holding company on top of another, none of which did anything but to hold securities of the companies below it. The scheme allowed stockholders of the top company to control the assets of operating companies with very little investment. Samuel Insull was one of the kings of these empires. In 1930, his capital investment of $27 million allowed him to control electric companies and assorted other businesses in 32 states having assets of at least $500 million.

So lucrative was the holding company structure that their number increased from 102 to 180 between 1922 and 1927, while the number of subsidiary operating companies actually declined from 6,355 to 4,409. By 1932, only eight holding companies controlled almost three-quarters of the investor-owned utility business. Perhaps best of all for the holding companies, their operations usually were exempt from the investigation of state regulatory commissions, since so much of their business crossed state boundaries.

The abuses of holding companies invited a six-year investigation pursued by the Federal Trade Commission beginning in 1928. Public antagonism toward the companies intensified after the stock market crash of 1929 decimated the values of holding company securities. Campaigning for the presidency in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt lashed out against the “the Ishmaels and the Insulls, whose hand is against everyman’s,” and he vowed to reform the industry if he won election.

Federal Intervention

Public Power for Rural Customers

Keeping his word, Roosevelt created (with the consent of Congress) government agencies that generated and distributed electricity to segments of the American public neglected by investor-owned utilities (IOUs). IOU executives had previously argued that electrifying rural areas would be too expensive and would not provide adequate returns on investment, but the Tennessee Valley Authority (created in 1933) and the Rural Electrification Administration (1935) proved otherwise. These and other institutions demonstrated that electrification of even the poorest households could raise standards of living of the inhabitants and produce good income to electricity suppliers. (In 1930, only 10% of American farms had electrical service; by 1945, almost 45% of them were wired up.) As a result of these actions, investor-owned utilities have been deprived, to this day, of a significant portion of the country’s customers–customers who are served by municipal utilities or rural cooperatives.

Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935

Beyond embarrassing utility executives with these initiatives, the federal government imposed new rules on the investor-owned utility industry. By passing the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, Congress outlawed the pyramid structure that had been at the core of financial abuses. Holding companies could remain, but they could only have two levels–one holding company on top and one or more operating subsidiaries below. Meanwhile, the law dissolved holding companies that did not contain contiguous operating utilities; earlier companies held operating companies that were scattered about the country and could not take advantage of consolidated or interconnected operation. Moreover, all interstate holding companies and practically all businesses that produced a substantial amount of electricity would be forced to register with the newly created (in 1935) Securities and Exchange Commission. Furthermore, they were required to follow its strict rules about submitting financial reports, and they needed to obtain approval to issue stock and bond securities.

By not outlawing holding companies altogether, these New Deal initiatives recognized the engineering and management value that holding companies could provide to operating companies. Nevertheless, the number of holding companies declined, from 216 to 18 in the period between 1938 and 1958, while hundreds of operating companies became separated from holding companies altogether. The landscape of the utility industry remained fairly consistent since then: about 77% of generated kilowatt-hours were produced by investor-owned companies in 1970, while municipal and government utilities (and rural cooperatives) produced the remaining 23%.

Assessment of FDR’s Reorganization

During the early years of his presidency, President Roosevelt had the opportunity to transform forever the utility industry. Having public and political support behind him after the holding company abuses became widely known, he could have urged that state and federal power agencies (such as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Bonneville Power Authority in the Pacific Northwest) assume the assets and activities of privately owned utility companies. But this was not what he did. Instead, the President sought to impose safeguards, in the form of government oversight of holding companies and securities issuance, to prevent abuses in the future. As in other areas of his New Deal, the President sought to preserve the sanctity of the private capitalist economy and not destroy it. In the process, he gave investor-owned utility companies another chance to demonstrate that their natural monopoly industry could indeed provide benefits to society.

Post World War II “Golden Years”

Overview

After the SEC had finished its work of divesting holding companies, generally between 1938 and 1955, the utility industry enjoyed a period often described as “the Golden Years.” Regulatory intervention from states and the federal government was minimal, and utility companies generally satisfied their investors and customers. The happy period would last until around 1970, when storm winds suggested that the energy world was about to change and that old assumptions and business practices could no longer remain unaltered.

Growth

The pent-up demand for electricity and electrical appliances after World War II sent utility companies scurrying for capacity. Usage jumped 14% between 1946 and 1947, but power firms could not get enough equipment to meet demand as labor troubles at manufacturers and reconversion to a peace-time economy stalled deliveries. But as the immediate post-war constraints alleviated themselves, the growth rate slowed to about 8% per year nationally from between 1947 and 1973. At this rate, utilities doubled the amount of electricity sold every nine-to-ten years.

Increased Scale

Happily for electric utilities, technological advances in generating and transmission technologies allowed them to produce more power at lower marginal costs. One form of technological advance came from increasing the scale of steam turbine-generators–the technology that used fossil fuels to covert raw energy into electricity. As Samuel Insull realized early in the 20th century, the hearty steam turbines could be expanded in size to deliver more power but at lower unit costs. Throughout the decades, the major manufacturers, which included General Electric, Westinghouse, and Allis Chalmers in the United States, built steam turbine-generators of increasingly large capacities.

Insull’s 5 MW and 12 MW units were followed in the industry by units as large as 110 MW in 1928. The Depression of the 1930 stalled rapid growth of electricity demand, but after World War II, manufacturers built bigger units again. In 1953, the first 220 MW unit appeared, to be followed in 1960 by a 575-MW unit. The 1,000 MW threshold was broken in 1965, when the Consolidated Edison Company of New York installed its “Big Allis” unit. By 1972, the honors for the largest unit went to a 1,300 MW behemoth. Until these latter units were installed, utility companies generally found that the unit cost of power declined as the scale increased.

Better Thermal Efficiency

On another front, technological advance provided real benefits too. When Thomas Edison burned coal to power his Pearl Street plant, only about 2.5% of the raw energy could be converted to electricity. But as electric power production became a more prominent activity, manufacturers of boilers and turbines found ways to improve that thermal efficiency rate. By heating water to higher temperatures and pressures and by improving the metallurgy of the turbines–so they could withstand the more oppressive conditions of the steam–they could raise thermal efficiency dramatically, thus getting more kilowatt-hours out of a ton of coal or barrel of oil. By 1920, the best power plant obtained just under 20% thermal efficiency, while in the 1960s, some plants obtained about 40%. On average, power plants in the 1960s converted about one-third of the fuel energy into electricity.

Transmission Voltages Grow

Transmission systems also witnessed stepwise improvement throughout the history of electric power, and technological improvements in this area also helped reduce costs and prices. As understood by the 1890s, alternating-current power could be transformed to high voltages and sent over transmission lines with little energy loss, compared to transmission at low voltages with direct current. After demonstrating the success of the Niagara Falls transmission line at 11,000 volts, manufacturers increased voltages to 60,000 volts in 1900, 150,000 volts in 1912, and 240,000 volts in 1930. Higher voltages reduced energy losses–a major advantage–but they also enabled more power to be transmitted through the same wire, in the same way that more water can be forced through a pipe at high pressure than at low pressure. Thus, high-voltage lines could carry more power and to greater distances.

The advances allowed utility companies to connect their power systems together, which enabled them to back each other up during emergencies (when one company’s power plant unexpectedly failed, for example), thus raising reliability of power supply. Interconnections also allowed utility companies to sell excess power to neighboring utilities when the economics benefited both customers. In such cases, the transactions also benefited customers, who saw lower prices, and stockholders, who saw their companies reduce their costs and earn extra income. Overall, advances in high-voltage transmission and interconnections complemented technological progress being made simultaneously in steam turbine-generating units.

Price Declines

Overall, the technological advances in generating and transmitting electricity allowed the utility industry to show productivity gains that dwarfed the American economy overall. From 1899 to 1953, for example, the utility industry demonstrated a productivity growth rate of 5.5% per year, which compared to 1.7% annually for the entire private domestic economy. Utilities continued to swamp the rest of the economy in productivity growth rates into the late 1960s.

While impressive to economists, these productivity gains had a more substantive effect on customers, who watched the price of electricity decline. Adjusted to 1992 terms, a residential customer in 1892 paid more than 4 dollars for each kilowatt-hour, a price that explains why electricity was viewed as a luxury item at the time. But by 1907, the price had dropped by more than half, to $1.56 per kWh. As utilities pursued incremental technological advances, prices fell to 55 cents in 1927 and 19 cents in 1947. Progress continued in the post World-War II period, such that the price of electricity dropped to 13 cents per kWh in 1913 and 9 cents in 1967.

Grow and Build Strategy

The combination of technological progress and cost (and price) declines became codified in a business approach sometimes known as the “grow-and-build” strategy. Following Insull’s pioneering example, utilities promoted the use of electricity usage so they would have reason to build new and more productive power plants. The plants produced power at lower marginal cost, which meant that expenses per unit of electricity declined. Part of that lower cost would be passed on to customers as lower rates. When prices fall, customers usually buy more of the product, and the same occurred in the electric power realm. Lower prices stimulated growth in usage, which meant utilities needed to build new power plants to meet demand, but those plants could further exploit technological advances and attain still lower costs.

The strategy helps explain why utility companies, especially in the post-World-War II period, heavily promoted the use of electricity through the use of “Live Better Electrically” and “All-Electric Home” advertising campaigns. After all, growth in electricity usage appeared to be universally beneficial, helping utility companies, their customers, manufacturers of equipment, sellers of electrical appliances, and stockholders. The approach even satisfied regulators, who sat back with little to do as everyone seemed to profit from a well-operating electric utility system.

Energy Crises of the 1970s

Overview

The good times for the utility industry would not last forever. A combination of “macro-economic” events occurring outside the realm of the industry and the apparent end of progress with traditional technology within the industry challenged the grow-and-build strategy in the 1970s.

Most people who think back to the energy problems of the 1970s point to the Arab oil embargo of 1973 as the event that triggered economic and energy malaise for the United States. While the embargo certainly began what became known as the “energy crisis,” it was not the first event that suggested problems with the American energy system.

Growth Spurts and Problems Meeting Demand

Hints of problems occurred in the late 1960s, when demand for electricity in some parts of the country exceeded the traditional 7-to-8% annual growth rate, and when some utilities could not build enough capacity. (Virginia Electric Power Company, for example, witnessed 14% per year spurts in the late 1960s as a result of rapid population and industrial growth in its service territory.) While the companies ordered equipment from manufacturers, a large backlog of requests for huge turbine-generators from other companies, combined with delays occurring during construction of the plants, meant that some firms could not meet demand. During the blistering hot summer days of 1967 through 1969, some utilities on the east coast reduced voltage as one way to deal with increased demand, causing “brownouts,” while they asked customers to reduce power consumption.

Fuel Shortages before 1973

Compounding the problem, utilities sometimes could not buy enough fuel to heat the boilers that powered the turbine-generators. While the most abundant fuel in the United States, coal came in short supply as mine operators opened few new mines in the 1960s, convinced that utilities would move to adopt new nuclear power plants, which powered their boilers with small amounts of uranium. Shortages of natural gas also occurred in the early 1970s, causing some factories in the industrial midwest to shut down. At the same time, electric utilities increased their dependence on oil, because it burned more cleanly than coal, and because the public and Congress had become concerned about the environmental effects of producing electricity.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 put further environmental pressure on utilities, and they increasingly bought oil from the Middle East, whose oil contained less pollution-causing sulfur. Unfortunately for utilities, as American production of oil peaked and then declined, the Middle Eastern countries, which had created the Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960, began flexing its muscles and demanded increased royalty payments from oil companies, thereby sending prices up. The overall energy situation became so precarious that, in 1971, President Nixon called on Congress to pass legislation for enhancing production of energy resources while also encouraging conservation.

The Energy Crunch Begins

But the county’s energy problems truly became raised to a high state of consciousness after the OPEC countries embargoed their oil in October 1973 to countries that supported Israel during the Arab-Israeli War. Begun on 6 October, when Egyptian forces attacked Israel on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year in the Jewish state, the war lasted into the next year, with Israel occupying territory formerly held by Egypt and Syria. To punish western supporters of Israel, however, Arab supporters within OPEC stopped shipping oil them. When they lifted the embargo in early 1974, they raised the price of oil dramatically, from under $2 per barrel before the October war, to more than $12.

The United States depended on OPEC oil for under 15% of the country’s petroleum needs, but it proved critical for transportation and industrial needs. The price hikes rippled throughout the energy industries and caused alternative fuels, such as coal, to increase in price as well. As one manifestation of the energy crisis, Americans impatiently waiting in lines at gas stations to pay higher prices for rationed petroleum products. As another manifestation, the higher energy prices caused the cost of other goods to increase, spurring the inflation rate to jump to about 10% by early 1975. Investors in the stock market had little to cheer about either. As consumers spent more money on energy and less on other goods, business activity slowed, and the Dow Jones Industrial average dropped 45% from its 1973 high to its 1974 low. President Nixon tried to urge the country to conserve resources and develop new sources of energy, so that the country would become energy self-sufficient by 1980. Incapacitated politically by the Watergate scandal, however, the President could not lobby effectively with Congress to pass effective emergency legislation in 1973 or 1974.

Technological Problems

From Edison’s day through the 1960s, utilities enjoyed the ability to obtain more kilowatt-hours from each unit of fossil fuel. In the 1950s, manufacturers drove up steam temperatures and pressures and could achieve, with the best unit, about 40% thermal efficiency. But even at this level, problems occurred that made utility managers wary of trying to exceed this point. When the hot, super-pressurized steam pressed against the parts of the turbine, it caused metallurgical fatigue that caused reliability to decrease and maintenance costs to increase, even with the specialized (and expensive) metals that were used. As a result, utility economists realized that lower-efficiency plants might be more economical to operate. Though they would not eke out the last kWh out of a barrel of oil, they would be cheaper to build and less costly to maintain. While making economic sense, though, the decision to stop pushing thermal efficiencies yet higher also meant that utilities could no longer expect to see cost declines from this source of technological advance.

The other source of cost reductions came from increasing the capacity of turbine-generators. Though utilities ordered power units in ever-larger sizes, they found in the late 1960s and early 1970s that economies of scale no longer were automatic. It appeared that metallurgical problems began occurring with the huge blades attached to the massive turbine shafts when they reached and exceeded the 1,000 MW mark. Moreover, as the big units became more complex, they seemed to endure more failures than their smaller counterparts, partly because of faulty design strategies undertaken by manufacturing companies. Some economists posited that the optimum capacity of power units remained in the 500-to-900 MW range, and utilities after the early 1970s stopped ordering gigantic units as a consequence. (The slower growth rate of customer usage after the energy crisis also suggested that utilities did not need as many of the huge units.)

Of course, some people pointed to nuclear power plants as the answer to the energy crisis. After all, the plants heated water in a nuclear boiler (with the rest of the plant ideally similar to fossil-fuel burning plants), but it used a fuel–uranium–that was not controlled by OPEC and which produced a lot of heat from small amounts of the material. Unfortunately for nuclear’s proponents, this technology had problems as well, as its opponents made increasingly clear to the public. First of all, nuclear power plants emitted more thermal waste than fossil plants, and that thermal pollution became subject to environmental protection laws. Complying with the laws caused the cost of the plants to increase as manufacturers developed means to cool the output before it re-entered rivers and oceans. Perhaps more importantly, the redundant safety systems of the plants, which were designed to prevent leaks of dangerous radioactive materials and by-products, were shown to be inadequate in some circumstances. When challenged by the Union of Concerned Scientists in 1972, for example, the Atomic Energy Commission admitted that the vital safety feature of nuclear plants may not have been as reliable as previously believed. Accidents at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Brown’s Ferry nuclear plant in 1975 and the near-meltdown of the Three Mile Island nuclear unit in 1979 further convinced many people that the risks of nuclear power might not be worth the supposed benefits of inexhaustible supplies of nuclear-electricity.

At the same time, these plants also became increasingly complex and difficult to construct, thus raising their cost dramatically. Even if the energy cost of the nuclear plants were near zero, the capital costs were huge–sometimes as high as five-times the average cost of construction for more conventional plants in the 1970s and 1980s. That feature alone suggested to many people–nuclear opponents and utility executives–that nuclear power would not pull the country out of the energy crisis by itself.

Net Effects of the Crises

Higher Prices

As energy prices increased and as technological progress in generating electricity failed to mitigate those higher prices, customers and others quickly became disenchanted with the utility system. Having paid only 2.2 cents per kWh in 1969 (in current terms), the average residential customer in 1977 paid almost double that rate–just over 4 cents. As rates increased, customers made efforts to reduce consumption. During the crisis period between 1973 and 1974, electricity usage actually dropped 0.1%. The next year, it grew at 1.9% per year, and it rose for the next several years by about 2.5% annually, which compared to a 7-to-8% rate before the crisis.

Customer Unrest

As can be imagined, customers did not enjoy watching their rates and bills increase, and they complained to state regulators. Unfortunately, regulators found themselves in an unusual position and ill-prepared to deal with the new stresses resulting from the energy crisis. On one hand, they had an obligation to the public to assure that they obtained a reliable supply of electricity at “fair” prices. On the other hand, they needed to assure the financial integrity of power companies so power would always be available to customers. To accomplish the latter task, commissions usually acceded to requests by utility companies for higher rates to pay for the greater costs of constructing power plants and the fuel that fed them.

Regulation Unable to Cope

At the same time, regulators generally had few tools and skills for immediately helping to resolve a difficult situation. During the golden years of the utility business, regulators had little to do but to approve rate decreases. Thus, commission work did not attract the best and brightest individuals. In many states where governors had the prerogative, the elected officials appointed members of commissions in return for political favors. Rarely was a commissioner appointed because of his or her recognized ability to understand issues of public utility finance or management. Moreover, with limited funding from state legislatures, commissions could not hire the expert and inquisitive type of staff members who could develop innovative solutions to difficult problems. As a result, regulation–even after the energy crisis hit–proved to be fairly unimaginative and acquiescent to the demands of utility companies, often to the chagrin of customers who paid higher rates.

An Unforgiving Economy Troubles the Utility Industry

The higher fuel prices that were passed on to utility customers were just one of the sources of complaint by ratepayers. Utility managers too disliked watching their business, which they honestly believed provided an essential product for social and economic progress, being criticized by customers, politicians, and anyone else who seemed to need an easy target. But the executives also fretted because other costs had begun to skyrocket as well; these costs too would ultimately be reflected in higher rates.

Interest Rates Soar

One such cost was that of growing interest payments on bonds that utilities floated so they could pay for construction of new plants. But with inflation rising, partly because of the energy crisis, so did the cost of borrowing money. Through the 1950s, utilities could borrow money at 5% or so annual rates. As inflation soared in the 1970s and early 1980s, the companies were forced to pay more than 15% or more, and that was if they enjoyed good credit ratings. At that rate, a bondholder received the equivalent of his or her invested capital back in interest payments in fewer than six years. When building the delayed and troubled Shoreham nuclear power plant, the Long Island Lighting Company spent $1.5 million a day in interest payments in 1984, which contributed to the firm’s brush with bankruptcy.

Escalating Construction Costs

Overall, the cost of building large power plants became a headache to utility companies. Having lost the benefit of economies of scale, new plants would have costs that reflected the staggering price increases seen in an inflationary economy. When operating, the plants would not benefit from increased thermal efficiencies; hence, rates would continue to rise along with fuel costs. Because of the increased complexity of the large plants, they took longer to construct. Coal burning plants ordered in the late 1960s and 1970s took an average of eight years to complete; nuclear plants, because of changing safety and environmental regulations–especially after the near meltdown of a Three Mile Island unit in 1979–took about 12 years to finish. During these years, interest payments had to be maintained to bondholders. Since most states did not allow utilities to recover the cost of plants until they were up and running, the power companies had to fork over huge sums of money years before earning a cent of return on their investments.

Stock Market Reflects Utilities’ Woes

The poor financial condition of utilities was accurately reflected by the stock market. Reaching heights not seen since before the Great Depression started in 1929, utility stocks peaked in 1965 at the height of the “Golden Years.” A decade later, utility stocks had been discarded by many investors, who saw only dim prospects ahead for a beleaguered industry.

The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA)

President Carter’s Philosophy about Conservation

When he moved into the White House in January 1977, after presidents Nixon and Ford found it impossible to make much headway on energy “independence,” Jimmy Carter vowed to be different. Making energy matters a top priority, he went before the American public in April and announced the outlines of a bold new plan. Equating the energy crisis with the “moral equivalent of war,” he chastised Americans for being the biggest wastrels of energy in the world. He further reflected the influence of energy-efficiency advocates, such as S. David Freeman and Amory Lovins, who pointed out that much of America’s energy needs could be found by developing and using appliances and manufacturing equipment that used less energy to do the same tasks as more inefficient devices. Carter pointed out that conservation was the “quickest, cheapest, most practical source of energy,” and he made it the cornerstone of his new policy.

Encouraging Conservation

To encourage conservation, the President advocated the use of carrots and sticks: he sought tax credits to spur individuals and businesses to insulate their homes, stores, and factories, thus reducing energy use. He also lobbied for acceptance of a tax on gasoline–rising to 50 cents a gallon–if consumption did not decline as mandated, as well as a tax on “gas guzzler” cars.

Exploiting Other Energy Resources

While conservation may have been the cornerstone of his new policy, Carter also sought development and exploitation of other energy resources. He sought greater production of coal and oil and further use of nuclear power plants, for example, though he hoped the extra production could be achieved without adversely affecting the environment. And he hoped that alternative energy devises, such as solar cells, geothermal energy, and wind turbines, would receive federal funding and other incentives so they could produce power without being dependent on fickle foreign suppliers of petroleum.

Managing Supply and Demand

Many of these goals had been sought by previous presidents. But President Carter seems to have been the first to understand clearly that the energy crisis had two elements. The most public element consisted of the apparent shortage of energy supplies. Consumption patterns of the recent past meant that Americans would need ever-increasing supplies of energy. But the country could no longer produce all the energy it needed domestically. America simply did not have enough energy to go around. So it now was forced to draw on supplies from abroad, which incurred high political, military, and economic costs.

The less public element of the energy crisis focused on the demand side. Americans had become accustomed to the ability to secure inexpensive energy, and they neglected energy efficiency in favor of convenience and pleasure. Why ride the bus to work when driving a powerful car to work was more convenient and when gasoline cost less than 30 cents per gallon? Why insulate your house when oil and electricity prices hit record lows? As a result, energy demand grew exponentially, though supply did not. Carter realized that if the growth in energy demand could be slowed, or even reduced, then the effects of the energy crisis could be mitigated. In short, he made energy conservation the cornerstone of his new policy and the basis of long-term energy independence rather than just a short-term fix to current woes.

End of Promotional Rate Structures

As one part of his National Energy Plan, debated by Congress in 1977 and 1978, President Carter suggested changes to the way power companies charged for electricity. Typically, utilities offered customers a “rate structure” that encouraged them to use increasing amounts of electricity. It did this by charging higher prices for the first increments of electricity used by customers–for example the first 50 kWh–with subsequent increments costing less per unit. One New York utility in 1973, for example, charged 4.4 cents per kWh for each of the first 50 kWh of use, but only 3.9 cents for the next 60 kWh, 3.4 cents for the subsequent 120 kWh, and only 2.8 cents for each unit greater than 240 kWh.

During the golden years of the utility industry, this “promotional” rate structure made sense, as utility costs continuously declined and as growing demand pushed costs still lower. But with technological progress limited and energy costs climbing, power companies no longer could achieve lower costs. Moreover, the rate structure encouraged people to use more electricity at a time when conservation was becoming the nation’s watchword.

Signed into law in November 1978, the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) focused on eliminating promotional rate structures except when they could be justified by the cost structure of utility companies. In most cases, they could not be so justified, so the law required state commissions to order utilities to develop new rate structures. Most utility managers did not worry too much about the law, and they were able to comply with it. In fact, some utility companies executives thought they got off fairly easily with this provision, being more worried about other terms of Carter’s energy plan that required them to convert from burning oil to coal and prohibitions against the use of natural gas.

Cogeneration Incentives

But one minor portion of PURPA mostly escaped the attention of utility managers. It required utility companies to purchase power from industrial companies that produced electricity as a by-product of other activities. In other words, a paper company that needed steam would boil water and first send the steam through a turbine-generator and produce some electricity for use in the factory. The waste steam would be used for industrial processes. In this way, usually more than 45% of the energy content in the raw fuel would be used for productive purposes–several percentage points better than the best utility power plant. Unfortunately for a company that used this “cogeneration” process, it usually could not find a market for electricity it produced in excess of what it used internally.

President Carter and his staff saw this situation as a lost opportunity to improve the energy efficiency of producing power, and PURPA contained a provision that required local utilities to buy excess power from these so-called “qualifying facilities” (or “QFs”) at very favorable rates–rates equivalent to their cost of producing power by conventional means. Often, this “avoided cost” was higher than the price companies paid for purchasing electricity from the utility. But in most cases, cogenerated power was cheaper than utility-generated electricity, despite the lack of scale economies, because the fuel was used to perform double-duty: it produced steam for industrial activities and electricity for internal use and sale to the electrical grid. Moreover, the company could produce and sell power without being subject to the regulations dealing with security registration or prices that utilities were forced to endure.

Gas Turbine Technology

Developments in gas-turbine technology helped make cogenerated power especially attractive. In essence, a gas turbine is an aircraft engine, powered by natural gas, that is attached to a generator. Much electricity is produced directly from the generator, but in a cogeneration scheme, the waste heat from the engine’s exhaust is used for industrial purposes or to heat water and send the steam through a more traditional steam turbine generator. Again, the raw fuel gets used to make two products, thus enhancing overall thermal efficiency. Moreover, during the military buildup of the Reagan presidency, manufacturers of jet engines received government funding for research and development to advance the efficiency and reliability of the technology. Seeing another market for similar equipment, manufacturers modified the jet engines for use in electricity production. By the early 1990s, gas turbine cogeneration units could be installed quickly and obtain thermal efficiencies in the 50% range–well above that achieved by central station utility plants.

Alternative Energy

PURPA provided similarly favorable terms to entrepreneurial companies that produced electricity from solar cells, wind turbines, and other renewable (i.e., non-fossil-fuel) resources. In some states, such as California, where the regulatory commission established favorable terms for the new power producers, alternative energy flourished. Dozens of companies sporting various types of wind turbines, for example, set up shop, and technological innovation in the technology advanced rapidly. By 1990, the price of wind-generated electricity dropped about 80% (compared to 1980), making it competitive with utility-generated power, especially power produced by expensive nuclear plants. Cost reductions of the same magnitude occurred for making electricity from the sun, though it still did not compare to utility costs. But California’s commission still provided incentives for its production as a way to continue the downward trend in costs. As a result, by 1990, California had become the home of 85% of the world’s capacity of electricity powered by the wind and 95% of the world’s solar-powered electricity.

Technological Innovation

Overall, PURPA provided a tremendous–and unanticipated–spur to technological innovation on numerous non-traditional technologies for producing electricity. From gas turbines to wind turbines, from solar cells to geothermal generators, PURPA enabled small, start-up entrepreneurial firms and larger, established companies to enter the generation business. Of course, this goal was anticipated by President Carter and his staff. They hoped that, given the proper incentives, a useful source of domestic energy production could be marshaled to stave off demand for petroleum and other resources from abroad. By 1995, about 9% of all electricity produced in the United States came from PURPA QFs, up from about 2.5% in 1985.

PURPA’s Consequences

While hoping for non-conventional sources of power to come on line as a result of PURPA, no one anticipated the changes that the law would have on the regulation of electric power and the overall structure of the electric utility system. Even before utility companies won designation as natural monopolies, they had established themselves as vertically integrated firms. In other words, they undertook all the functions of generating, transmitting, and distributing electricity to the ultimate customer. Conceivably, one can imagine any of these three functions being performed by different companies, but early utilities became protected as regulated monopolies partly on the assumption that one company could produce power more efficiently and economically as one company than as several. Since utility companies had already been vertically integrated by the time regulation became imposed, they remained so structured thereafter. Few people thought to question an alternate arrangement, and utility managers, who sought to maintain control over as much of their business as possible, certainly would not offer to divest their existing companies.

But unintentionally, PURPA started that questioning process because it enabled non-utility generators (sometimes called “NUGs”) to produce power for use by customers attached to a utility’s grid. In other words, the law broke the stranglehold on power companies’ previous monopoly in the generation function. Now, any unregulated cogenerator or renewable energy producer could sell electricity into the power grid, with regulated utilities helpless to dictate terms.

In a sense, however, PURPA did not create a competitive market for power yet. After all, the PURPA QFs did not literally compete with regulated utilities since those companies were required by law to purchase whatever power came their way from the cogenerators and alternative power generators. Still, the PURPA producers caused real grief to many utility managers, since the new players represented a source of power they could not control. The QFs sold power into the grid whenever they wanted, or whenever they had excess power remaining in a cogeneration plant, and utility managers had to find ways to limit their own production, or boost it, to ensure that customers obtained the power they needed without interruption.

In another sense, however, the PURPA producers constituted a definite competitive threat. Because the QFs usually obtained a price equivalent to the cost utilities would incur when they generated power, the independents by definition could produce power as cheaply or cheaper than could utilities. Though cogenerating equipment cost more than hardware that only produced only electricity, the salability of steam, which had a value of between 1 and 2 cents per kilowatt-hour, allowed cogenerated electricity to be less expensive than that produced by many utility companies. The competitive pricing situation would not have existed in the 1940s or 1950s, however, since utility companies could still exploit economies of scale and increasing thermal efficiencies. But when utilities ran into technological limits to traditional progress, unconventional power production techniques proved cost effective. In a similar vein, electricity produced from natural gas turbines owned by PURPA entrepreneurs became increasingly attractive, as the price of natural gas fell from a peak in the mid-1980s, and as the technology became more efficient. Again, economies of scale meant less than economies involved in mass producing small (approximately 100 MW) gas turbines.

These realities of electricity production made many people within and outside the industry question one of the rationales for acceptance of utilities at natural monopolies and, consequently, the justification for regulation. In the theory accepted early in the 20th century, electric power production and distribution constituted a natural monopoly because, by dint of huge capital investment in expensive generating equipment and associated facilities, one company could produce power more economically than could competitive firms. Many companies in the same market would not enjoy the large market of diverse customers, and they would be limited to using smaller and less-efficient equipment. All customers, therefore, would be deprived of the benefits that could be accrued if only one company produced power for an entire market.

But the end of technological progress combined with the economic woes of the 1970s and 1980s turned this argument upside down. It now appeared, thanks to incentives provided by PURPA and innovation in small-scale technologies, such as gas turbines, that non-utility companies could produce power as cheaply or more so than could regulated firms. As a result, many people began suggesting that the fundamentals of the power industry needed to be re-evaluated. In 1983, William Berry, president of the Virginia Electric and Power Company, realized earlier than most of his utility colleagues that “[a]s in so many other regulated monopolies, technological developments have overtaken and destroyed the rationale for regulation. Electricity generation is no longer a natural monopoly.” Congressmen and members of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the body that has authority over interstate transactions of electricity, reflected similar sentiments in the 1980s. In short, the existence and success of PURPA QFs appeared to destroy one important justification for regulation of utilities.

A New Era for Electricity

Energy Policy Act of 1992

Though failing to pass Congress in 1991, President Bush’s Energy Policy Act passed the following year. Containing measures that would help spur production of domestic energy resources, such as a credit for electricity generated from renewable resources, the law also contained measures for creating greater numbers of producers of power along more conventional means. For example, it created a new class of producers called Exempt Wholesale Generators, which could generate power any way they saw fit and without regard to energy efficiency concerns (as was the case for PURPA QFs). The measure increased competitive pressure on existing generating companies and utilities in the same way as a new supermarket in town would force others to become more efficient and cost-conscious.

Utility companies won some new rights under the Energy Policy Act as well. The law allowed utilities to own some EWG facilities, even outside their franchise area. Conceivably, then, a utility on the west coast could own generating facilities on the east coast if it believed the practice made good financial sense. Moreover, utilities did not even have to keep all their business in the United States. If they saw profit opportunities abroad, they could purchase companies there, so long as customers of domestic operations were not disadvantaged.

On another front, utilities also won a major concession. While the law required utilities to open their transmission systems to other companies that sought to wheel power over them, only wholesale transactions were permitted. While some lobbyists for large industrial electricity users sought to permit sales to retail customers, so they could take advantage of cheap power wherever it came from, the law limited sales to wholesale customers. These included other utility companies, municipal power systems, and rural electrification networks, which would then resell the electricity to ultimate customers.

Though the federal law limited sales to wholesale customers, it left the door open for competition on the retail level. It did so by allowing state legislatures and regulatory commissions to take the final step by allowing suppliers to sell electricity all customers–whether they be big factories or small residential households. Within a few years, several states began plans to pass through that open door.

The academic economists and ideologues who liked the idea of increased competition in the utility business were not alone. Real, practical business people felt that the introduction of market principles could benefit customers and lead to introduction of new services and better prices than could the existing system. So did other interested parties.

The promise of competition stemmed in part from the greatly disparate prices paid by customers across the nation. Under traditional regulatory practice, every state commission helped determine rates paid by customers for each utility in the state. The rates were based on the value of the equipment used to generate, transmit, and distribute electricity, plus the actual cost of variable expenses such as fuel, within the state. In some parts of the country, such as California and several New England states, rates were high, partly because of the high cost of construction and fuel in general but also because of utilities’ building of nuclear plants whose costs escalated due to delays and construction headaches. In other parts of the country, however, utilities employed relative cheap fuel that powered older and largely depreciated power plants.

Industrial customers typically used large amounts of power, and their rates usually were lower than for residential customers. Nevertheless, in California and New England, big industrial users paid more than 7 cents per kWh in 1995 on average. In Nevada, however, rates averaged between 5 and 7 cents per kWh. Meanwhile, some low cost states, such as those in the Pacific Northwest, which drew much power from flowing water rather than fossil fuel, and in states that had ready access to cheap coal, rates dropped to between 2.8 and 5 cents per kWh. Imagine how a California industrial customer, paying more than 7 cents per kWh would have liked to obtain power from a company just across the border in Oregon, where rates were half that rate! Yet, under regulation, California customers could not directly buy the Oregon power. No wonder large industrial users were among the most eager to see regulatory restraints lifted so they could have access to cheaper electricity around the country.

Additionally, independent generators (PURPA QFs and EWGs) that used natural gas-burning turbine-generators found they could easily underprice existing utilities. With the generating equipment becoming cheaper, due to mass production techniques, and with natural gas prices dropping since being deregulated in the mid-1980s, the independents could offer electricity to large customers at about 3 cents per kWh, well below the rate most utilities could offer. Who wanted to pay 7 cents or more per kWh to a regulated utility when independents could exploit new technology and low fuel prices to produce power at such a cheap rate?

Other parties also saw advantages in allowing competition between suppliers and between utilities and generators in various states. One such group included the independent power producers, those generators empowered by PURPA or by the Energy Policy Act who set up business outside the traditional utility system. They felt they could get better prices for their electricity if they had the opportunity to sell to a larger number of customers, both near them and far away.

And under the right conditions, environmental and consumer groups also looked forward to competition. Generators that used renewable resources or those the used natural gas–a fuel that burned more cleanly than coal or oil–would also have a larger potential market if traditional rate regulation were relaxed. Even residential customers could look forward to lower rates if they could attract low-cost providers to sell power to their service areas.

Opponents of Competition

Of course, not everyone liked the prospects of increased competition. A large number of regulated utilities, especially those in high-cost states, for example, feared the prospect of competition, largely because they still owned expensive assets that would not allow them to sell electricity as cheaply as new entrants into the business. For example, a company that operated an expensive nuclear power plant would need to charge higher rates–to recover the costs–than would an exempt wholesale generator that bought an inexpensive gas turbine-generator and used cheap natural gas. According to these opponents of competition, regulated utilities would be holding “stranded costs” due to their purchase of assets (such as power plants and long-term contracts with independents) made in a formerly regulated environment, when they had an obligation to serve all customers. In a competitive business, that obligation would be waived, but the companies would be responsible for paying off expensive power plants acquired earlier. If no compensation were made for these stranded costs, they argued, there could be no “level playing field” upon which all parties competed fairly.

At the same time, some consumer groups feared that competition would short-change the small residential customer. On one hand, the promise of competitors knocking on the doors (or calling on the phone at dinner time) and offering new rates had appeal. After all, a similar situation occurred when telecommunications services underwent deregulation, leading to generally lower long-distance telephone rates. But in the electricity business, would there be enough electrons to go around to all users? Since there were just so many generating plants in the country, maybe the low-cost providers would compete primarily to obtain contracts with the largest and easiest-to-serve industrial customers. Individual residential customers use much less power than industrials, and they would have to be contacted individually, thus raising the cost of doing business with them. As a result, competition also raised the specter of residential rates increasing because all the cheap producers would sell their power to large users. Only the high-cost producers would remain to serve residential customers.

Overseeing utilities that sold power at nearly the highest rates in the Union, California regulators since the 1980s had investigated various methods to introduce competitive principles into the electricity supply business. But the Energy Policy Act of 1992 gave regulators the chance to pursue comprehensive restructuring of the utility business. It took advantage of the opportunity in 1992, by beginning a study of regulation’s history and prospects for change.

Following publication of the commission staff’s report in 1993, numerous hearings, further proposals, and still more public hearings, the California legislature took control of the restructuring process in 1996. By August 1996, legislators had bargained with numerous interest groups and passed unanimously a bill, signed by the governor in September, that would allow retail customers to choose their suppliers of electricity by January 1, 1998. (At first, only large customers were allowed to shop for power by 1998; later modifications opened the competitive market to all customers by New Year’s Day, 1998.)

The California law should not necessarily be viewed as a model upon which other laws will be passed. Rather, it is described in some detail because it deals comprehensively with several of the major issues being debated around the country. Laws in other states can deal with the same issues in different ways.

Features of California’s Restructuring Law

Due to the need to ensure a level playing field, the law created a new infrastructure for transmitting and selling electric power so that no one company would have excessive “market power”–the power to inhibit transactions and make competition among other companies difficult. Conceivably, a formerly regulated utility company could charge high rates to other firms for transmitting power over its transmission lines, thus giving itself a major advantage. The California law remedied this potential problem by establishing an “Independent System Operator,” which would control utilities’ transmission networks (without actually owning them), coordinate scheduling of power supplies, and ensure open access of the lines to all power providers. Simultaneously, the state created a “Power Exchange” for maintaining a competitive marketplace where suppliers could offer electricity and where buyers would come to purchase power. Both institutions would operate without discriminating against any party, and both would be overseen by a board composed of members nominated by state regulatory bodies and by members of the state legislature.

Competitive markets only work when there are lots of sellers and lots of buyers. To help ensure that an existing utility does not have too much control over the market, California power companies were required to divest some of their assets. In other words, the companies needed to sell some of their generating stations, for example, so they would not dominate the market of those who wanted to sell power to the Power Exchange. By divesting these assets, market share would be spread among a greater number of players, thus leading to a more competitive environment that would benefit buyers of electricity.

The California restructuring law had something for all types of consumers, which perhaps explains why it won unanimous support in the legislature. First of all, it allowed customers in all classes to choose their suppliers of power. This provision benefited large industrial customers particularly, since they eagerly sought the opportunity to buy power from independents or utilities anywhere within or outside the state. But before getting the full benefits of competition, these customers (and any others leaving their previous utility supplier) would be required to pay a “competition transition charge”–something like a tax that would go to pay for utilities’ stranded costs (estimated at up to $30 billion) and other publicly valuable programs. This feature of the law pleased utilities, which would undoubtedly lose some of their most prized customers.

The law also recognized that utilities previously provided several functions that were viewed as socially valuable but which would not be provided by competitive companies. These functions included encouragement of conservation and energy-efficiency efforts, spurring technological advances on alternative (and low-pollution) technologies, and providing electrical service for low-income residents.

As a result of these concerns, the California law required continued spending of almost $900 million to spur energy-efficiency work until 2001–work that budget-trimming companies sought to eliminate because it made the cost of their electricity more expensive (and hence, less competitive). Meanwhile, $250 million would finance research and development on new technologies that were not yet commercially viable, but which might be within a few years. Renewable resource technologies would get another $540 million. At the same time, low-income customers would retain subsidies and assistance so they could maintain electrical service–something cut-throat competitors might be loathe to provide.

Meanwhile, residential customers who feared that the benefits of competition might pass them by would obtain an immediate 10% rate decrease and another 10% discount by 2002. After then, legislators hoped the restructured utility business would have found mechanisms, such as firms that aggregated residential customers and brokered lower rates for them, so that small electricity users would profit from competition without government mandates.

Other States Pass Restructuring Laws

Even before California passed a law restructuring its utility system, other states had made similar efforts. But none was as comprehensive as California’s. Moreover, due to the Golden State’s economic clout and position as a trend-setter, its new law would have a tremendous impact on events in other states.

Interestingly, the state of New Hampshire was the first state to develop a pilot program of actual retail competition. With the highest retail rates in the country, largely because its major regulated utility built the hugely expensive Seabrook nuclear power plant, New Hampshire had little to lose by allowing 11,000 residents to choose their electricity supplier, starting in May 1996. About thirty companies descended upon the state, eager to gain experience in the retail competitive market, and they offered lower prices along with inducements such as rebates, bird feeders, free ice cream, and the promise to sell only electricity generated with no or little environmental degradation.

In other states, restructuring activities picked up steam as well. By the spring of 1996, all but 10 states had started consideration of bills and regulatory actions that would have introduced competitive principles into the electricity supply business. Several states had pilot programs, while eight had already passed laws, by July 1996, setting up the rules for restructuring. In some states, stranded costs–a big issue to currently regulated utilities–were to be paid for by customers leaving their traditional utility company. In other states, companies and their stockholders were told to absorb those costs.