Overview

Paleoindian

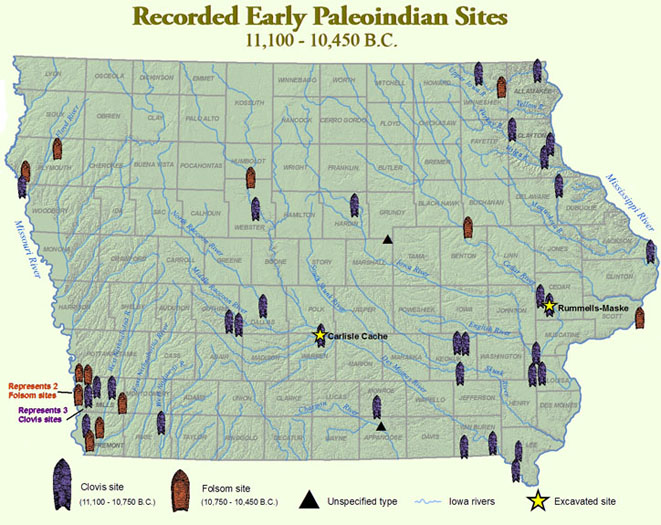

At the end of the last Ice Age, Iowa had a cool, wet climate and widespread coniferous forests. Paleoindian peoples (11,000_8500 BC) lived in small, highly mobile bands and hunted large game animals. Their tools included lance-shaped spear points and specialized butchering tools. They often used high-quality raw materials obtained from distant sources. Most known sites of this period represent kill sites or butchering areas; little is known of other site types. Paleoindian sites are rare, partly because population density was probably low.

Early Paleoindian points (11,000_9,500 BC) have been found in 42 of the 99 Iowa counties. Later Paleoindian points have a wider distribution. The best documented Paleoindian site in Iowa is the Rummells-Maske site in Cedar County, a cache of Clovis points recovered from a plowed field. Because Paleoindian sites are so rare in Iowa, interpretations of settlement patterns, subsistence systems, and other lifeways rely on comparisons to other parts of the country.

By 8500 BC, climatic change and large-mammal extinctions helped cause cultural changes marking the shift to the Archaic lifeways.

Archaic

The Archaic period in Iowa dates between roughly 8500 and 800 BC and can be further divided into the Early (8500_5500 BC), Middle (5500_3000 BC), and Late (3000_800 BC) Archaic. Environmental change occurred rapidly, with the expansion of prairie and then deciduous forests. Archaic peoples flourished throughout Iowa, hunting bison, deer, elk, and smaller animals, and gathering many types of plants. Their habitation sites included long and short term base camps as well as resource procurement camps.

Excavations near Cherokee, Iowa, revealed that Early Archaic bands were small and maintained a seasonal round of resource exploitation. During the Middle Archaic, environmental conditions became increasingly warm and arid, leading to settlement near reliable water sources.

The Late Archaic in Iowa saw a return to moister conditions, accompanied by overall population increase and the exploitation of previously unoccupied areas. Similar hunting and gathering patterns were spread over broad areas. Artifact styles also were similar over broad regions and trading networks were widespread. Greater environmental stability and diversity supported expanded populations and allowed a more sedentary way of life.

Ground stone tools, made by pecking and abrading igneous and metamorphic rocks, were added to the tool kit. Tool types included grooved axes, nutting stones, manos, metates, and others. These tools were used in pounding, grinding, crushing, and chopping activities in plant processing. A few Archaic burial sites have been found. Large cemeteries indicate the attainment of greater population densities and sedentary lifeways over time.

Woodland

The Woodland period in Iowa can be divided into the Early (800_200 BC), Middle (200 BC_AD 300), and Late (AD 300_1200) Woodland. Early in this period, the climate and landforms had stabilized to resemble those of today, and vegetation patterns became much like the forest-prairie mix encountered by nineteenth-century settlers. So although environmental changes drove the transition from the Paleoindian to the Archaic period, cultural changes were responsible for the transition from Archaic to Woodland.

The Woodland period saw major technological, economic, and social developments. The use of pottery, the bow and arrow, plant domestication and cultivation, and burial mound construction all became widespread. Population grew rapidly, and settlements spread across the landscape into most available niches.

In addition to intensive hunting and gathering, communities were raising crops such as goosefoot, marsh elder, squash, and tobacco by the Middle Woodland period. Corn was introduced later and became a staple by the end of the period.

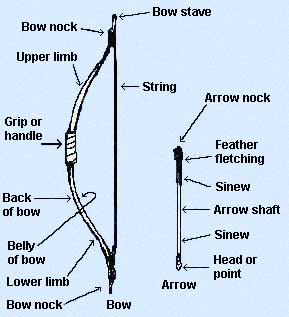

Bow and arrow technology was introduced during the Late Woodland period, most likely from the northern plains. Bow hunting is shown by small arrow points, which replaced large spear points.

Social interaction throughout the Midwest involved the widespread exchange of various cherts, Gulf Coast marine shell, Great Lakes copper, Appalachian mica, northern Illinois pipestone, and galena from northeast Iowa.

Pottery production began with cord-marked vessels, both thick walled, flat bottomed and thinner walled, bag-shaped styles. By the Late Woodland, pots were more globular. Woodland pottery decorations were made by cord impressions, fabrics, incised lines, and punctates.

In the Middle Woodland, trade networks expanded, art works were more elaborate, and mortuary practices became more complex. The “Hopewell” interaction network connected Iowa societies to those in many other regions. Although widespread trade dropped off by the LateWoodland, the interaction between groups continued. Conical-shaped Woodland burial mounds were built throughout the Midwest. Most Early and Late Woodland mounds were small or medium in size and relatively simply constructed. Middle Woodland mounds were typically large, with complex construction. Elaborate, exotic artifacts interred with some individual burials suggest a special or higher status. Effigy mounds, in the shape of birds, bears, lizards, and occasionally humans, were constructed in northeast Iowa and adjacent states from AD 650 to 1000. The Late Woodland people who built these mounds lived in dispersed groups, merging seasonally with related family units into larger social groups. The effigy mounds were possibly used as indicators of territorial control by loosely related families.

Late Prehistoric

The Late Prehistoric period (ca. AD 1000_1650) is divided into several cultures including the Great Oasis, Mill Creek, Glenwood, and Oneota. Improved corn varieties, food surpluses, new storage methods, improvements in pottery technology, earthlodge houses, and greater complexity in social and political organization were common to most of these peoples. The use of bison increased for meat, hides for clothing and dwelling coverings, and bones for tool manufacture. Groups practiced a mixed economy of hunting and gathering and intensive horticulture. Crops included corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, tobacco, and a variety of native species.

Great Oasis

The earliest Late Prehistoric group was the Great Oasis, whose sites are found across northwest and north-central Iowa. Villages were located on low terraces above the floodplains of rivers and streams and on lake shores. Larger villages may have been occupied throughout the late fall, winter, and early spring with smaller villages occupied during the summer for horticultural activities. Pottery was primarily of three types—high, wedge, and S-shaped rims—and the decorations were applied by carefully incised lines in a variety of designs.

Mill Creek

The Mill Creek people occupied villages in northwest Iowa and are a part of the Middle Missouri Tradition. Their sites appear as deep midden deposits on terraces above the Big and Little Sioux Rivers and their tributaries. Compact, well-planned villages were often fortified with palisades and encircling ditches and contained several earthlodges with large internal storage pits. Mill Creek peoples had long-distance trade connections with peoples of the Mississippi River valley, including the large urban center at Cahokia near East St. Louis. It has been speculated that the Mill Creek peoples moved up the Missouri River and may have been part of the root culture that later developed into the Mandan tribe.

Glenwood (Nebraska Phase)

The “Glenwood culture” represents the expansion of Central Plains Tradition peoples into southwestern Iowa. Their dispersed earthlodges are found along ridge summits, terraces, and side valleys along the Missouri River and its tributaries. Pottery vessels are globular forms with smoothed-over cord-marked bodies and decorations about the rim or collar. Glenwood people may have eventually moved north and west, combining with other groups that may be ancestral to the Arikara and Pawnee peoples.

Oneota

Oneota people lived in most of Iowa between about AD 1200 and 1700. Oneota sites have been found throughout the Upper Midwest. Villages were large, semi-permanent or permanent. Early houses were small, square to oval, single-family dwellings. In later times, large longhouses for many families were built. Large pit features were used for storage of food and other items. Pottery differs from that of other Late Prehistoric peoples as it was shell tempered, which allowed the manufacturers to create thinner, stronger walled vessels. Archaeological, ethnohistorical, and linguistic evidence strongly suggest that the Oneota in Iowa continued into the Historic period and can be identified as ancestral to the Iowa and Oto-Missouria peoples.

Historic

The prehistoric period in Iowa ended at the time of contact between Native Americans and Euroamericans during the late 1600s and early 1700s. Archaeological study has revealed much about Iowans of the historic period.

Indian groups whose historic habitations have been documented by archaeology include the Iowa, Meskwaki, and Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) peoples. Native crafts such as flintknapping and pottery making declined as European manufactured goods became more common. Villages and whole tribes moved often because of increased warfare, territorial pressure, and trading opportunities. Tribes maintained their cultures, languages, and identities despite huge changes in almost every aspect of life.

Archaeological study of trading posts, frontier forts, early farmsteads and factories, and townsites shows how non-Indians settled into the landscape. Material from such sites adds an important dimension to the written record of Iowa history.

Native American Archery Technology

American Indians did not always have the bow and arrow. It was not until about A.D. 500 that the bow and arrow was adopted in Iowa some 11,500 years after the first people came to the region. Primary benefits of the bow and arrow over the spear are more rapid missile velocity, higher degree of accuracy, and greater mobility. Arrowheads also required substantially less raw materials than spear heads. A flint knapper could produce a large number of small projectile points from a single piece of chert. Even with the gun’s many advantages in the historic era, bows and arrows are much quieter than guns, allowing the hunter more chances to strike at the prey.

Indians used arrows to kill animals as large as bison and elk. Hunters approached their prey on foot or on horse back, accurately targeting vulnerable areas.The choice of materials and the design of arrows and the bow were not random. Some materials were generally more readily available than others. Environmental conditions also affected the choice of materials. Humidity affects wooden bows, and temperature affects horn and antler. The intended use of the system, on foot or horse back, for instance, affects the final design. Bows used while mounted on horseback tend to be shorter than the bows used when on foot. Since the length of the bow determines the stress placed on the bow when drawn, shorter bows tend to be made of composite materials while bows used when on foot can be made of wood.Indians used a variety of materials to make the bow stave, relying on materials that met certain requirements, most important of which is flexibility without breaking. Several species of plants and some animal materials met these requirements.

Ash, hickory, locust, Osage orange, cedar, juniper, oak, walnut, birch, choke cherry, serviceberry, and mulberry woods were used. Elk antler, mountain sheep horn, bison horn, and ribs, and caribou antler also were used where available.Bow construction techniques included a single stave of wood (self bow), wood with sinew reinforcement (backed bow), and a combination of horn or antler with sinew backing (composite bow). Hide glue was used to attach the backing. Bow strings most frequently were made of sinew (animal back or leg tendon), rawhide, or gut. The Dakota Indians also used cord made from the neck of snapping turtles. Occasionally, plant fibers, such as inner bark of basswood, slippery elm or cherry trees, and yucca were used. Nettles, milkweed, and dogbane are also suitable fibers. Well-made plant fiber string is superior to string made of animal fibers because it holds the most weight while resisting stretching and remaining strong in damp conditions. However, plant fiber strings are generally much more labor intensive to make than animal fiber strings, and the preference in the recent past was for sinew, gut, or rawhide.

Arrow shafts were made out of shoots, such as dogwood, wild rose, ash, birch, chokecherry, and black locust. Reeds from common reed grass were also used with some frequency throughout North America with the exception of the Plains where reeds did not grow. Shoots were shaved, sanded, or heat and pressure straightened. Tools made of bone or sandstone were used to straighten the shaft wood. Because they are hollow and light, reed-shaft arrows typically have a wooden foreshaft and sometimes a wooden plug for the nock end of the arrow. If a foreshaft was used, it could be glued to the main shaft, tied with sinew, or fit closely enough to not need glue or sinew.Prehistoric points or heads were made of stone, antler, or bone. Thin metal, bottle glass, and flint ballast stones also were used to make points in the historic period.

Points were attached to the arrow shaft with a variety of methods. Most frequently, the arrow shaft would have a slit cut into the end to accept the point. Sinew would then be wrapped around the shaft to pinch the slit closed. Points could also be hafted directly by wrapping sinew around the point and the arrow shaft. Metal points generally were attached using the same techniques and only infrequently attached by means of a socket.

Indians made many types of arrowheads. In addition to the traditional triangular stone arrowhead, carved wood or leather points have large, broad surfaces. Different types of arrow tips were used for different purposes, such as for large game versus small game. Small triangular stone points are not bird points: large, blunt-tipped wooden points were used for birds. Harpoon-like points also exist and were used in fishing.

Fletching of bird feathers was sewn to or inserted in the shaft. Feathers of wild turkey were preferred but many other birds, including eagle, crow, goose, hawk, and turkey, were often used. Sinew was generally used to attach the fletching by first stripping some of the feathers from the front and back of the vane and then tying the vane to the shaft in front of and behind the remaining feathers. Sometimes plant twine was used to sew through the quill. Hide glue was used with or instead of sinew ties. Animal products like sinew have the advantage of tightening as they dry.

The fletching balances the weight of the arrowhead to prevent the arrow from tumbling end-over-end in flight. When fletched properly, an arrow may spin in flight producing an ideal trajectory. A similar effectiveness is gained by placing grooves in the barrel of a rifle to cause the bullet to spin. In fact, until the invention of rifled guns, bows generally proved to be more accurate and could shoot arrows further than powder-thrown missiles.The bow and arrow is a complex technology. Each element must be balanced in proportion to the others and to the user to make an effective tool. The bow acts as a pair of springs connected by the grip or handle. As the string is pulled the material on the inside or belly of the bow limbs compresses, while the outside or back is stretched and is placed under tension. This action stores the energy used to draw the string back. When the string is released, the limbs quickly return to their state of rest and release the energy stored by drawing the string. Therefore, the power of a bow is measured in terms of draw weight.

The height and strength of the archer determines the ideal draw weight of the bow. A combination of the length of draw and the draw weight of the bow determines the cast (propelling force) of the bow. Adjusting either or both of these features allows the arrowhead to be made larger or smaller as needed.The draw weight of the bow also determines the ideal weight and diameter of the arrow shaft. Even a bow with a high draw weight can only throw an arrow so far. If the arrow is too heavy, it will not fly far or fast enough to be very useful. A shaft that is too thick or too thin will also lead to problems. It must compress enough to bend around the bow stave as it is launched by the string. If it does not bend, the arrow flies to the side of the target. If it bends too much, it will wobble (reducing the striking force) or even shatter.

The length of the draw, also determined by the body of the archer, determines the length of the arrow. The Flintknapping is the making of flaked or chipped stone tools. This technology was used in historic times to manufacture gun flints and in prehistoric times to make spear and dart points, arrow heads, knives, scrapers, blades, gravers, perforators, and many other tools.aximum cast of the bow determines the maximum weight of the point. This is how we know that certain “arrowheads” can not really have been used on an arrow, at least not to any good effect. A general rule of thumb is that a stone arrowhead will be less than 1 1/2-x-3/4-inch in dimensions and will generally weigh less than one ounce. Larger “arrowheads” probably would have been spear, dart, or knife tips.

Flintknapping

Flintknapping is the making of flaked or chipped stone tools. This technology was used in historic times to manufacture gun flints and in prehistoric times to make spear and dart points, arrow heads, knives, scrapers, blades, gravers, perforators, and many other tools.

Flintknapping requires the ability to control the way rocks break when they are struck. The best rock is somewhat brittle and uniform in texture and structure, lacking frost fractures, inclusions, or other flaws. This type of rock is very fine grained or non-grained. The best rocks for flint-knapping are chert, flint, chalcedony, quartzite, jasper, and obsidian. Chert and flint are silica-rich rocks found throughout the Midwest in limestone and dolomite deposits. These rock types, when struck with another rock, piece of antler, or bone, will fracture or break in a characteristic pattern called a conchoidal fracture. This creates a rock fragment called a flake.

Flakes have specific features identifying them as the result of human hands rather than natural processes. All flakes typically have a striking platform (A), bulb of percussion (B), eraillure (C), radial fissures (D), ripple marks (E), and negative flake scars on the dorsal side from earlier flake removals (F). You can think of these features in terms of dropping a rock in a still pond: the rock hitting the water (A), the splash (B), the drops that fly away from the splash (C), the drops that fall back near the splash (D), and the concentric waves moving outward (E). Naturally broken rocks usually do not exhibit these features.

The production process begins with a piece of raw material, called a core. Flakes are removed by striking the edge of the core with a sharp, forceful blow, in what is called percussion flaking.

Percussion flakes are removed using a hard hammer or soft hammer. Hard hammers are typically made of igneous or metamorphic rocks such as granite, quartz, basalt, or gneiss. Hard hammers tend to pass most of their energy to the core without absorbing much of the force, so they are used to flake large cores of hard materials. A carefully controlled strike is always more important than a hard strike when using a hard hammer.

A soft hammer is made of a piece of antler, although bone and some very hard woods can be used. Moose, deer, elk, and caribou antler are all usable soft hammers. Soft hammers are used when flaking very brittle material such as obsidian or when greater control is needed. Soft hammers will not pass as much energy to the core and will absorb some of the force, affording greater control of the size and shape of the removed flake. Edges being worked must be ground dull prior to flake removal. This dulling helps prevent edge collapse. A piece of sandstone, very soft limestone, or other soft rock may be used to dull the edge.

Indirect percussion flaking is a process where some device holds the core or flake being worked, leaving both hands free to drive off flakes with greater force or precision. One hand holds a punch-like piece of antler or bone against the core while the other holds a hammer and strikes the punch to drive off flakes. This combines the accuracy of pressure flaking with the force of percussion flaking.

Another method of flake removal is pressure flaking.

The knapper detaches flakes by applying leverage (pressure) to an edge. An antler tine, piece of bone, or hard wood sharpened for accurate application of force is needed for flake removal. Downward and outward pressure pops the flakes off. This method can straighten and sharpen edges of a finished tool or shape a tool from flake to final form.

Flakes can be used for simple tasks or can be further reduced to make various types of tools. A small amount of shaping can turn a flake into a knife, scraper, or other useful implement.

A biface is any chipped tool produced by flaking of both surfaces. Each stage reflects progressive reduction of a core or large flake. The desired product might be a projectile point, knife, or drill. Bifaces and other tools were usually repaired and resharpened frequently, extending their use-lives but reducing their sizes until they were discarded.

Heat treatment improves the knapping quality of some raw materials. It requires gradual application of high heat. The color and luster of the rock often change noticeably, and the flaking quality of the rock improves because its texture becomes smoother and less grainy. Heat treatment is usually applied to small and medium cores, flakes, or bifaces; larger pieces are difficult to heat evenly and thoroughly. To begin the process, a good sized fire is burned down to glowing coals and hot sand. A pit is excavated and the remains of the old fire placed into it (A and B). Already warmed chert pieces are placed into the pit (C) and covered with sand. A new fire is built and allowed to burn out over a 24 hour period before digging up the heat treated pieces. Care must be taken, for heat treatment can cause rocks to fracture explosively.

Flintknapping is a fun and interesting hobby which can provide considerable insight into the lives of prehistoric peoples. Chert, flint, and other rocks usable for flint-knapping can be acquired from local quarry operators, rock shops, stream beds, and other gravels, or by knowing your local geology. Antler and bone for hammers can be obtained from your local meat locker or butcher.

Flintknapping is very dangerous. Cuts are common and can be severe. Always wear safety glasses, knap outside, and make it easy to clean up by using a tarp. Work where your flakes will not be mistaken for a real archaeological site, because the methods described here can produce flakes identical to prehistoric flakes. Try using your flaked stone tools in your garden or kitchen to see how well they work and learn more about the lifeways of stone age peoples.

Bone Tools

Overview

Ancient Iowans used many kinds of animal bones as raw material for tools. Along with artifacts of stone, shell, and wood, bone implements were an important part of many tool kits. As a raw material, bone is tough and slightly brittle. With only slight modifications, the scapulae (shoulder blades) of bison and elk could be made into hoes, and the ulnae (foreleg bones) of deer could be worked into awls. Other types of tools such as fishhooks required considerable labor to reach their desired form.

Manufacturing Techniques

Softer than most stone and harder than wood, the hardness and resilience of bone made it particularly useful. Fresh bone can be split, broken, and splintered. Relatively fresh bone can be modified in various ways, depending on the form and size of the bone and the type of tool desired.

Bone Breaking

The simplest means of modifying bone is by breaking the bone on an anvil with a large hammerstone. This technique was commonly employed to extract nutritious marrow from the bone cavity. Long bones of large.animals can be cracked and broken into sharp splinters suitable for immediate use as picks or scrapers or for further modification into awls and other tools. This technique of breaking bones is relatively haphazard, but when coupled with other methods such as grooving or sawing, it can be used to shape more sophisticated tools.

Grooving and Splitting

For some delicate bone tools, it is first necessary to score the parent bone. Grooves outlining the intended tool’s form are cut through the hard outer bone to the spongy cancellous tissue using stone tools such as sharp pointed gravers and chisel-ended burins. The piece can then be broken free with relative ease and made into an awl or needle. Grooving bone with a modified flake tool can be slow. Soaking the bone in water for a few days can speed up the process by temporarily softening the bone, making cutting and scraping easier. Once the bone is dry, it will return to its hard, resilient state.

Sawing, Drilling, and Grinding

Bone can be sawed into sections with a serrated bifacial stone knife or flake tool. After the saw cuts have been made to a sufficient depth, the bone can easily be broken by hand. Stone drills, either hand held or attached to shafts, may be used to bore holes through bone for making such tools as arrow-shaft wrenches. The small eyes of sewing and matting needles can be made by a sawing or twisting motion with a graver tip.

Polishing, final shaping, and sharpening were done with a sandstone abrader. Some tools were made almost totally by grinding.

Bone Tool Types

Since bone is not a universally well preserved material, we know little about the bone tool technologies of the cultures prior to the Late Prehistoric period. One of the earliest musical instruments, however, a bone flute, was recovered from an Early Archaic site in western Iowa.

After AD 1000, bone tools are well known. The Mill Creek culture of northwest Iowa (ca. AD 1000_1250) exhibits a particularly rich assemblage of bone artifacts. Bone tools are often categorized according to their supposed functions.

Hoes

Late Prehistoric agricultural groups of the Midwest and Plains commonly made hoe blades from the scapulae of bison and elk. The long spine that runs the length of the bone may be easily broken off after a few deep saw cuts have been made. Portions of the bone may be broken away to give the blade a more symmetrical appearance. After the edge has been beveled and ground sharp, the hoe blade is ready for mounting in a split and notched wooden handle.

Knives

So-called squash knives also were made from the scapulae of large mammals. These tools were made by selecting a portion of the broken shoulder blade and grinding the thin interior bone edge sharp. Such tools would have served well in slicing soft plant materials.

Scoops

Scoops were made from the bison horn core and accompanying portion of the frontal bone. These tools were probably made by breaking off the desired piece of the skull and grinding the exposed edge sharp. Horn scoops were probably used as hand-held digging tools.

Fleshers

Saw-tooth-edged tools were commonly made from the long bones of large animals, particularly the metatarsals (long foot bones) of bison and elk. By breaking the distal end off at an angle and then sharpening and serrating the exposed edge, the tool could be used to strip the fatty tissues from the inner surfaces of fresh hides.

Hide Grainers

Tools for scraping and smoothing the inner surfaces of hides were made by breaking off the heads of a leg bone of a bison or other large mammal, exposing rough cancellous interior bone.

Sickles

Deer jaws were used in an unmodified state for threshing grasses. The front portion was frequently worked away and polished smooth.

Arrow-Shaft Wrenches

The ribs of bison and elk as well as the long bones of deer were sometimes drilled with holes for use in straightening arrow shafts. When arrow shafts were heated, these wrenches helped remove warps or irregularities.

Fishhooks

Fishhooks were made by two methods depending on the bone used. Toe bones of deer were cut and split lengthwise. The exterior surface of the bone was then removed by grinding, leaving only the hook-shaped ridge of bone inside. Larger fishhooks were made by grooving and grinding oval-shaped pieces of a split rib.

Awls

Awls, used as leather punches in sewing hides, were made from a variety of bones. The ulnae of deer could be cut, and then ground and polished to form a sharp tip. Splinters of rib and long bone were also ground into awls. Hollow bird bones also were sometimes broken and split to form awls.

Quill Flatteners

So-called quill flatteners are flat-ended tools made from long splinters of mammal bone. The rounded and flattened ends of these tools are thought to have been used in flattening porcupine quills for use as decoration. They may also have been used as pressure flakers in flintknapping or for smoothing in pottery making.

Antler Artifacts

Like bone, antler is tough and resilient. Unlike bone, however, antler is relatively solid and varies greatly in form among individual deer. Antlers are grown by male deer and are shed each winter. Antlers were perhaps most important to prehistoric groups for use as flintknapping tools. Soft hammer batons for controlled percussion flaking were made from the basal portions of antlers by cutting them to length and grinding off the rough burr at the base. Antler tips, cut to lengths of 3 to 10 inches, were used as pressure flakers. Antler tips were sometimes cut and drilled to make conical arrow points.

Ground Stone Artifacts

A wide range of prehistoric artifacts were formed by pecking, grinding, or polishing one stone with another. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other macrocrystallineigneous or metamorphic rocks, whose coarse structure makes them ideal for grinding other materials, including plants and other stones. Native Americans used cobbles found along streams and in exposures of glacial till or outwash to produce a variety ground stone artifacts. The process by which ground stone tools are manufactured is a labor-intensive, time-consuming method of repeated pecking and grinding with a harder stone, followed by polishing with sand, using water as a lubricant.

In North America, axes, celts, gouges, mauls, plummets, and bannerstones began to appear early in the Archaic period, made from hard igneous or metamorphic rocks. Cobbles with small shallow cupped depressions, called anvil stones or nutting stones, also came into use during the Archaic period. Discarded ground stone tools sometimes later became convenient raw material for use in stone boiling, lining roasting pits, or ringing hearths, thus ending their useful life as fire cracked rocks.

To facilitate hafting, axes were grooved, either completely around the four faces of the tool, or on three of the four faces. These groove patterns thus give rise to the terms “full” and “threequarter” grooved axes.

Rarely, grooves were placed only on the two flattened faces of an axe; in the Midwest such tools are known as Keokuk axes. Celts are similar to axes but lack the groove and were hafted with the bit perpendicular to the axis of the handle, rather than paralleling it, as with an axe. Axes, celts, gouges, and mauls are generally considered to be woodworking tools and are often found in areas that were once forested or still retain the native tree cover.

During the Late Archaic, Woodland, and Late Prehistoric periods ground stone technology began to be applied to softer sedimentary and metamorphic rocks for making other kinds of artifacts. For example, limestone was used for making pipes, hematite for celts, sandstone for arrow shaft abraders, and small bowls were shaped from steatite.

Catlinite is a relatively soft, reddish metamorphic rock found in southwestern Minnesota that is wellknown for use in calumet and disc-bowl pipes by Plains tribes. With the development of horticulture came the need for tools to process grain, and large flat blocks of quartzite or granite were pecked and ground into dishshaped grinding stones called metates to grind corn or other seeds into meal.

Some ground stone tools were created incidentally by abrasion with other tools. Manos, for example, are handheld stones used in conjunction with metates or grinding slabs, and develop their ground surfaces through wear. Cobbles used as hammerstones in flintknapping and ground stone pecking retain the scars developed from use, often appearing as pitted and flattened areas along their perimeters.

Ground stone technology also was used to produce artifacts of personal adornment. Gorgets, beads, and ear spools enhanced the appearance of the bearer and perhaps functioned as status symbols. Such artifacts were drilled to permit suspension from a cord by spinning a narrow pointed stone, hardened stick, or bone between the hands against the stone, using sand as an abrasive. The hole was drilled part way through on one side of the object and the remainder of the hole was drilled from the opposite side.

The drilling process results in a biconical hole that is narrowest near the middle of the object. Larger-diameter holes could be drilled using a hollow bone or reed along with sand and water. A by-product of the hollow drill was a narrow cylindrical core of the parent rock. Such cores of drilled ground stone artifacts have been found on archaeological sites.

A few very special artifacts were used in the ritual or ceremonial realms of certain prehistoric groups. At village sites of northwestern Iowa’s Late Prehistoric Mill Creek culture, small lens-shaped quartz or basalt discoidals and thunderbird effigies of limestone and catlinite have been found. The discoidals resemble old style ceramic or brass doorknobs in size and shape and are sometimes simply referred to as “doorknobs” by artifact collectors. Larger, biconcave stone discs four to five inches in diameter called chunkey stones were used by Mississippian societies of the southeastern part of the continent in a game of the same name.

Similar items have been found on Late Prehistoric Oneota villages in northwestern Iowa. Along with grinding and drill for pipes, catlinite also lends itself well to fine line engraving with a sharp tool, and a few small catlinite tablets engraved with complex symbols and pictographs have turned up on northwestern Iowa Oneota sites.

Prehistoric Pottery

Pottery was important to ancient Iowans and is an important type of artifact for the archaeologist. Ceramic pots are breakable but the small fragments, or sherds, are almost indestructible, even after hundreds of years in the ground. Pots were tools for cooking, serving, and storing food, and pottery was also an avenue of artistic expression. Prehistoric potters formed and decorated their vessels in a variety of ways. Often potters in one community or region made a few characteristic styles of pots. Because pots and styles were shared among groups, archaeologists can often relate sites in time and space because they contain the same ceramic types.

When ceramics are found at a site, they usually occur as small, broken sherds. Occasionally, all of the fragments of the vessel will have survived, and the pot can be reconstructed, just as you might work a jigsaw puzzle. When only a portion of a pot is left, archaeologists can rebuild the rest if enough remains to provide some idea of the original shape and size.

The first appearance of pottery during Woodland times approximately 2,800 years ago is significant because it indicates that people may have become more sedentary. Earlier peoples used lightweight, portable skin bags or woven containers made from inner bark of trees or reeds. Nomadic hunters and gatherers would not have wanted to carry heavy, breakable pots. When people began to settle in more permanent villages, however, they found many uses for pottery.

Pottery vessels were made from clays collected along streams or on hillsides. Sand, crushed stone, ground mussel shell, crushed fired clay, or plant fibers were added to prevent shrinkage and cracking during firing and drying.

Prehistoric pots were made by several methods: coiling, paddling, or pinching and shaping. In coiling, the potter rolls a lump of clay into a coil and gradually builds up the vessel wall by adding more coils. Each coiled layer is pinched to the one beneath and the coils are subsequently thinned by squeezing between the potter’s thumbs and fingers. Coil junctures are then smoothed.

In the paddling method, a lump of clay was pounded into shape by holding the clay against a large stone and paddling it with a wooden paddle. If the paddle was covered with woven fabric or a cord, the patterned markings appeared on the clay. The lump of clay might also be pinched and shaped by hand.

After air drying for an hour or two, the pot could be further thinned and shaped by scraping with a small piece of sharpened clam shell. After this scraping, a design could be applied by using fingernails or a tool such as an awl, stick, or wooden stamp.

Pots must air-dry at least two weeks before they are ready for firing. Firing was an all-day affair. An area would be cleared and a small fire built. The pots would be placed a small distance from the fire, turned every 15_20 minutes, and gradually moved closer to the fire. After a couple of hours, the pots would be placed directly on top of the hot coals. Immediately, wood was piled on until a roaring fire had been built. The fire was then allowed to burn down naturally. The pots were covered with ashes while they were cooling slowly. Variation in coloring on the fired pots is a result of the amount of oxygen present during firing—red from an oxidized atmosphere and gray from a reduced atmosphere.

Styles and decorations changed over the 2500-year-long history of native pottery in Iowa. Over time, a greater variety of pots—bowls, jars, and water bottles—were made for different functions. Sometimes tiny toy pots were made for or by children.

Much Woodland pottery is quite thick in comparison with pottery made by later cultures. The rims were often decorated with the edge of a cord-wrapped paddle, producing a set of vertical or diagonal impressions. The exteriors were cord marked by slapping the moist clay with the paddle. Complex designs often were applied through combinations of stamping, punctating, and incising the surface. Some vessels were decorated with fabric or cordage by impressing a woven design or geometric patterns into the moist clay. This makes it possible to study ancient weaving techniques even though the cloth itself has not survived.

Great Oasis ceramics are grit-tempered, globular-shaped pots with rounded bases. The smoothed-over cord-marked bodies were usually undecorated, but jar rims often were decorated with incised geometric designs.

Mill Creek potters made a wide variety of vessels including bowls, flat bottom rectangular pans, seed jars, wide-necked bottles, hooded water bottles, jars, and ollas (wide-mouthed water jars).

Rim form and decoration make Glenwood ceramics distinctive. Collared vessels were manufactured by thickening the rim with the addition of an extra band of clay (collar).

Classic Oneota pots are globular shaped with strap handles but made in a variety of sizes. Oneota pottery is shell tempered rather than grit tempered and is often decorated with geometric designs.

Indians in Iowa ceased making pottery in the 1700s as European-made kettles and other containers replaced the native ceramics.

Further Reading

- Ackerman, Laura B. 1985 The Bow Machine, Science 85, July/August, pp. 92-93.

- Allely, Steve, and Jim Hamm. 1999 Encyclopedia of Native American Bows, Arrows & Quivers: Volume I: Northeast, Southeast, And Midwest. Lyons Press, New York.

- Allely, Steve et al. 1992 The Traditional Bowyer’s Bible, Volumes 1-3. Lyons & Burford, New York.

- Crabtree, Don E. 1972. An Introduction to Flintworking. Occasional Papers No. 28. Idaho State University Museum, Pocatello.

- Hamilton, T. M. 1982 Native American Bows. Special Publications No. 5, Missouri Archaeological Society, Columbia, Missouri.

- Hamm, Jim. 1991 Bows & Arrows of the Native Americans. Lyons and Burford, New York. [Guide to construction.]

- Hardy, Robert. 1992 Longbow: A Social and Military History. Lyons and Burford, New York. [Appendix has detailed description of bow and arrow physics.]

- Hurley, Vic. 1975 Arrows Against Steel: The History of the Bow. Mason Charter, New York. [Discussion of effectiveness of the bow compared to firearms.]

- McEwen, Edward, Robert L. Miller, and Christopher A. Bergman. 1991 Early Bow Design and Construction, Scientific American, June 1991, pp. 77-82.

- Pope, Saxton T. 1962 Bows and Arrows. University of California Press, Los Angeles.

- Stockel, Henrietta H. 1995 The Lightening Stick: Arrows, Wounds, and Indian Legends. University of Nevada Press, Reno.

- Whittaker, John C. 1994. Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Originally published by the Office of the State Archaeologist, Iowa Academy of Science, The University of Iowa, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.