The lesson of the Pentagon Papers was not merely that the press prevailed in a landmark Supreme Court case, but that the state revealed the depth of its anxiety.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Press Freedom and the State’s Fear of Exposure

Press freedom in the United States has never been absolute, but its most important protections have emerged precisely at moments when the state feared exposure. When government power is exercised in secret, journalism becomes not merely informative but destabilizing, capable of revealing contradictions between public justification and private conduct. It is in these moments that constitutional commitments are most severely tested. The First Amendment does not promise comfort to those in power. It promises friction. The history of American press freedom is best understood not as a steady expansion of liberty, but as a recurring struggle over how much visibility the state can tolerate when its legitimacy is at stake.

The Pentagon Papers episode represents the clearest constitutional articulation of this struggle. When the New York Times and the Washington Post published classified documents detailing years of official deception regarding the Vietnam War, the federal government did not merely object. It attempted to stop publication outright, invoking national security as justification. The Supreme Court’s rejection of this effort in New York Times v. United States established a foundational principle: prior restraint on the press is presumptively unconstitutional except in the most extraordinary circumstances. Crucially, the Court made clear that embarrassment, political damage, or exposure of misconduct did not rise to that level. In doing so, it affirmed that democratic accountability requires a press capable of publishing information precisely when the state most wishes it would not.

Yet the constitutional victory of 1971 did not end government efforts to control the flow of information. Instead, it reshaped them. Having lost the ability to block publication directly through the courts, federal authorities increasingly turned to indirect methods of inhibition. Surveillance, investigation, prosecution, and enforcement-based intimidation emerged as tools capable of achieving similar effects without triggering the doctrinal barriers associated with prior restraint. These practices do not prevent publication in advance. They burden it afterward or deter it in anticipation. The distinction is legally significant, but functionally porous. Journalism constrained by fear of arrest, detention, or legal retaliation may be formally free while practically impaired.

What follows argues that modern enforcement actions against journalists should be understood within this longer constitutional and historical arc. Arresting a journalist for covering a protest does not replicate the Pentagon Papers case in form, but it echoes it in function. Both involve attempts to use law to inhibit reporting on controversial state action. Both rely on the language of legality to justify suppression. And both raise the same fundamental question: whether press freedom is protected only against overt censorship, or also against subtler forms of coercion that narrow the space in which journalism can safely operate. By tracing the legacy of New York Times v. United States forward into the present, this essay treats contemporary enforcement not as an aberration, but as part of an evolving struggle over visibility, accountability, and the limits of state power.

The Pentagon Papers: Government Deception and the Limits of Secrecy

The Pentagon Papers originated not as an act of journalistic investigation but as an internal government study commissioned by the Department of Defense in 1967. Officially titled History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy, the report traced American involvement in Vietnam from World War II through the mid-1960s. Compiled by analysts with broad access to classified material, it drew on memoranda, cables, policy drafts, and internal assessments that were never intended for public view. The study documented not simply policy debate, but a sustained pattern of contradiction between public assurances and private conclusions. Its purpose was retrospective and institutional, meant to help policymakers understand how the United States had become so deeply committed to a war it privately doubted it could win. The fact that such a study was commissioned at all revealed an acute awareness within government that official narratives had diverged sharply from internal reality.

At the center of the Pentagon Papers was evidence of systematic deception. Presidents and senior officials repeatedly assured Congress and the public that escalation was limited, progress was measurable, and victory was attainable. Internally, assessments acknowledged the improbability of success and the political motivations driving continued engagement. These contradictions were not incidental or isolated. They revealed a sustained effort to manage public perception in service of policy continuity. Secrecy functioned less as protection against foreign adversaries than as insulation against domestic scrutiny, preserving executive discretion by restricting access to inconvenient truths.

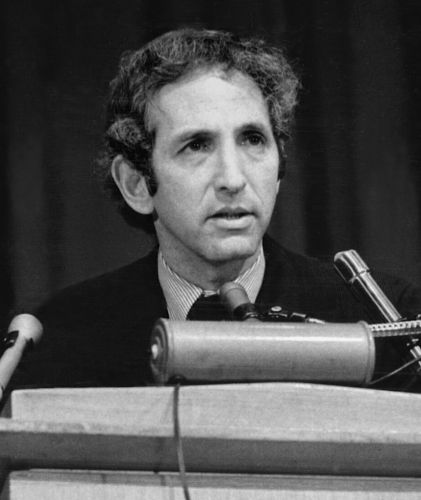

Daniel Ellsberg’s decision to disclose the study reflected this realization. As a former Defense Department analyst and consultant to the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg had participated directly in the production of the report. He concluded that the deception documented in the Papers was ongoing and that internal reform was unlikely. Ellsberg’s actions were motivated not by hostility toward the state but by a belief that democratic consent required informed judgment. By copying and distributing the documents to journalists, he sought to restore a measure of accountability to a system that had relied on secrecy to sustain policy failure.

The publication of the Pentagon Papers threatened the federal government not because it revealed tactical vulnerabilities, but because it exposed the mechanics of governance under secrecy. The documents demonstrated that elected officials had knowingly misled both Congress and the electorate across multiple administrations. This revelation challenged the legitimacy of executive authority itself, calling into question the moral foundation of decisions that had resulted in massive loss of life. The Nixon administration’s response made this concern unmistakable. Its primary anxiety was not the specific content of the disclosures, which dealt largely with past decisions, but the precedent of unauthorized exposure. The fear was institutional rather than operational. If secrecy could be pierced in this case, the executive branch risked losing its unilateral control over what the public was permitted to know.

The Pentagon Papers tested the limits of secrecy in a constitutional system more profoundly than any prior disclosure. They forced a confrontation between executive claims of authority and the press’s role as a conduit of public knowledge. The case raised foundational questions about who determines the boundaries of secrecy and for what purpose those boundaries exist. Is classification a tool for genuine national defense, or a mechanism for avoiding political accountability. By bringing these questions into public view, the Pentagon Papers transformed secrecy itself into a subject of democratic debate rather than an unquestioned administrative practice. The Supreme Court’s intervention would later clarify the legal stakes, but the deeper historical significance of the Papers lies in their exposure of secrecy as an instrument of power rather than a neutral necessity.

New York Times v. United States: The Constitutional Rejection of Prior Restraint

When the Nixon administration sought injunctions to halt further publication of the Pentagon Papers, it invoked one of the most forceful claims available to executive power: national security. The government argued that continued disclosure would cause irreparable harm to the United States, endanger lives, and compromise diplomatic and military operations. This claim rested less on specific evidence than on an appeal to institutional authority, asking courts to defer to executive judgment in areas the administration insisted were beyond judicial competence. The request was extraordinary in scope. It asked the judiciary to silence the press preemptively, not for what had been published, but for what might yet be revealed. At stake was not only the fate of the Pentagon Papers themselves, but whether courts would accept the proposition that asserted danger, rather than demonstrated harm, could justify suppressing publication in advance.

The Supreme Court’s response was swift and decisive. In a brief per curiam opinion issued in June 1971, the Court held that the government had failed to meet the “heavy burden” required to justify prior restraint. Although the justices did not issue a single unified rationale, the outcome was unmistakable. The injunctions were lifted, and publication resumed. The decision reaffirmed a core constitutional principle: the First Amendment sharply limits the government’s ability to suppress publication in advance, even when national security is invoked. The presumption against prior restraint was not merely strong; it was foundational.

The concurring opinions give the decision its enduring interpretive force. Justice Hugo Black, joined by Justice William O. Douglas, articulated the most absolutist defense of press freedom, arguing that the First Amendment left no room for judicial balancing when it came to publication. For Black, the press existed precisely to restrain government deception, not to accommodate it. Other justices adopted narrower but still consequential positions. Justice Potter Stewart emphasized the executive’s tendency toward secrecy and warned that unchecked classification threatened democratic accountability. Justice Byron White acknowledged that post-publication penalties might be constitutionally permissible in some circumstances, but insisted that prior restraint crossed a categorical line.

What united the Court was a rejection of speculative harm as a basis for suppression. The government offered no concrete evidence that publication would cause immediate, direct, and irreparable damage. Instead, it relied on assertions of authority and generalized claims of danger. The Court refused to convert those claims into law. In doing so, it established that embarrassment, loss of credibility, or exposure of past misconduct did not constitute national security threats sufficient to override press freedom. The decision thus drew a sharp constitutional boundary between secrecy that protects the nation and secrecy that protects power.

The significance of New York Times v. United States extends beyond its immediate holding. The case did not deny the existence of legitimate secrets, nor did it immunize journalists from all legal consequence. It did, however, foreclose the most direct and dangerous form of press suppression by placing prior restraint outside the ordinary reach of executive authority. In doing so, the Court forced the government to abandon injunctions as a primary tool of information control and to seek other, less visible methods of managing disclosure. This shift would prove consequential. The ruling closed one door while leaving others ajar, shaping a new terrain in which enforcement, surveillance, and post-publication pressure could assume greater importance. The Pentagon Papers case represents both a triumph and a turning point. It affirmed a constitutional safeguard while simultaneously redirecting the state’s impulse to control information into more indirect and adaptable forms.

The Afterlife of Prior Restraint: Winning the Case, Losing the War

The Supreme Court’s decision in New York Times v. United States closed the door on prior restraint as a routine instrument of executive control, but it did not extinguish the state’s interest in limiting disclosure. Instead, it forced adaptation. Having been denied the power to block publication in advance, federal authorities turned toward methods that operated after the fact or around the edges of journalism itself. The constitutional victory of 1971 marked not the end of press suppression, but the beginning of a more subtle and resilient phase. The state learned how to lose publicly while continuing to govern information privately.

One of the most significant shifts involved renewed reliance on criminal law as a deterrent rather than a remedy. Prosecutions under the Espionage Act of 1917, largely dormant for decades, reemerged as a mechanism for disciplining leakers and, indirectly, the journalists who relied on them. While the press was rarely charged directly, investigations, subpoenas, and aggressive pursuit of sources sent a clear signal about the risks attached to national security reporting. The emphasis moved from stopping publication to punishing disclosure, thereby increasing the personal cost borne by individuals involved in the reporting process. This strategy allowed the government to maintain the appearance of constitutional compliance while achieving deterrent effects similar to those once sought through injunctions.

Surveillance filled the space where injunctions once stood. Federal monitoring of journalists, their communications, and their professional networks expanded quietly in the post-Pentagon Papers era, often justified through broad national security authorities. Reporters covering defense, intelligence, and foreign policy found themselves subject to scrutiny not because of criminal conduct, but because of their proximity to sensitive information and sources. Such surveillance rarely resulted in formal charges, but it produced leverage, awareness, and deterrence. Knowledge that communications might be monitored altered newsroom practices and source relationships, encouraging caution and limiting investigative reach. The press could publish, but it could not do so without being watched, and that knowledge itself functioned as restraint.

Administrative pressure further extended this afterlife of restraint. Credentialing decisions, access restrictions, and selective enforcement of rules governing press presence at federal facilities became tools for shaping coverage. These measures were presented as neutral and procedural, yet they carried significant consequences. Loss of access could end a reporter’s ability to cover an institution effectively, while credential uncertainty encouraged compliance and caution. Because these actions were framed as administrative rather than punitive, they rarely triggered constitutional challenge, even as they narrowed the practical scope of press freedom.

The logic of deterrence also migrated into civil law and internal policy. Journalists faced increasing demands to reveal sources through subpoenas and contempt proceedings, even when formal shield laws existed. Internal government policies governing interactions with the press emphasized control, message discipline, and leak prevention. Together, these practices cultivated an environment in which journalists were formally free but operationally constrained. The absence of prior restraint did not equate to the presence of robust press freedom. It signaled only that suppression would take a different form.

The Pentagon Papers case produced a paradoxical outcome. The Court succeeded in preventing the most visible and constitutionally offensive method of press suppression, but it did not dismantle the incentive structure that made suppression attractive in the first place. The state adapted by distributing coercion across legal and administrative domains, lowering its visibility while preserving its effect. Winning the case meant losing the war over how information would be managed in a national security state. Prior restraint was rejected as doctrine, but restraint itself survived, reshaped into a durable system of post-publication pressure, surveillance, and procedural control that continues to define the relationship between journalism and power.

Policing the Press: Enforcement as Functional Prior Restraint

As formal prior restraint became constitutionally untenable after 1971, enforcement emerged as a functional substitute. Rather than seeking injunctions to block publication, authorities increasingly relied on policing practices that imposed costs on journalists after or during reporting. Arrests, detentions, equipment seizures, and criminal investigations did not prohibit speech outright, but they altered the conditions under which journalism could occur. In this sense, enforcement acted as restraint by other means. The press remained legally free, yet practically encumbered by the risks attached to witnessing and documenting state power.

This shift was especially visible in the context of protest coverage. Journalists reporting on demonstrations, civil unrest, and confrontations with law enforcement increasingly found themselves swept into enforcement actions ostensibly aimed at maintaining public order. Charges were often vague or temporary, ranging from failure to disperse to obstruction, trespass, or curfew violations. Even when dismissed, these actions served a regulatory function. Detention interrupted reporting in real time, confiscation of equipment delayed or prevented publication, and legal uncertainty discouraged future presence at similar events. The goal was not conviction, but disruption. Process itself became punishment, reinforcing the lesson that proximity to dissent carried tangible personal and professional risk.

Credentialing and access further reinforced enforcement as restraint. Press credentials, while often presented as neutral administrative tools, became mechanisms of control that could be expanded or withdrawn at discretion. Journalists without recognized credentials could be detained or excluded entirely, while those with credentials faced revocation, denial, or conditional access based on opaque criteria. These decisions rarely invoked overt censorship, yet they determined who could observe and report on state activity and under what conditions. Because access is foundational to journalism, its regulation functioned as a powerful form of indirect suppression, shaping coverage by narrowing who could be present and what could safely be reported.

National security and immigration enforcement magnified these dynamics. Journalists covering border operations, federal raids, or national security protests encountered expansive discretionary authority exercised in the name of safety, sovereignty, and emergency power. Detentions at borders, secondary screenings, device searches, and prolonged questioning blurred the line between reporting and suspicion. These practices operated within broad statutory frameworks, making them difficult to challenge while producing a chilling effect on investigative work. The ambiguity of enforcement, rather than its consistency, proved most effective. Journalists could not predict when scrutiny would escalate or what actions might trigger it, encouraging caution, self-limitation, and avoidance of sensitive coverage.

The cumulative impact of these practices was not uniform suppression, but managed visibility. Journalists adapted by altering assignments, delaying publication, or avoiding certain spaces altogether. Editors weighed legal exposure alongside editorial judgment, factoring enforcement risk into decisions that once rested primarily on news value and public interest. News organizations absorbed arrest, detention, and legal defense as routine operational costs, normalizing pressure that would once have been considered extraordinary. This environment did not eliminate investigative journalism, but it reshaped it. Coverage became more episodic, less embedded, and more cautious in moments of confrontation, reducing sustained scrutiny of state power where it is most contested.

Viewed historically, this pattern represents the logical evolution of state response to constitutional constraint. When courts foreclosed direct suppression, enforcement filled the gap. The resemblance to prior restraint lies not in doctrine but in effect. Both aim to control what reaches the public, one by blocking speech before it occurs, the other by burdening it until it becomes unsustainable. Policing the press in this way preserves the appearance of constitutional compliance while undermining the conditions necessary for robust journalism. It is this convergence of legality and coercion that renders enforcement a modern analogue of the restraint the Constitution was meant to forbid.

Don Lemon and the Modern Enforcement Model

The contemporary relevance of the Pentagon Papers framework becomes clearest when applied to recent enforcement actions involving journalists covering protests and federal operations. In public discourse surrounding the arrest or detention of journalists at demonstrations, the legal question is often framed narrowly: whether officers had probable cause, whether credentials were visible, or whether charges were later dismissed. This framing, while important, is incomplete. It isolates individual incidents from their institutional context and treats enforcement as episodic rather than patterned. What matters is not only legality in isolation, but cumulative effect. When a prominent journalist such as Don Lemon is detained or arrested while covering a controversial federal action, the incident operates symbolically as well as practically. It communicates to other journalists, editors, and news organizations where scrutiny may trigger consequence, even if no conviction ultimately follows. The enforcement action becomes a form of guidance, shaping behavior through example rather than statute.

The parallel to New York Times v. United States lies not in doctrinal equivalence but in functional resemblance. The Nixon administration sought to prevent publication because exposure threatened executive credibility and authority, not because the documents posed immediate tactical danger. Modern enforcement actions intervene at similarly sensitive moments, when journalism illuminates contested state power such as immigration enforcement in religious spaces, mass protests, or coercive administrative actions. Arresting or detaining a journalist does not stop publication permanently, but it interrupts it, burdens it, and reframes it as hazardous conduct. The journalist becomes part of the event being policed rather than an observer of it. As in 1971, the state’s concern is less about immediate harm than about precedent. If journalists can report freely on controversial federal actions without consequence, the ability to manage narrative and control institutional legitimacy diminishes.

The use of arrest rather than injunction reflects adaptation to constitutional limits. Courts have made prior restraint exceedingly difficult to justify, but they have not foreclosed enforcement discretion exercised in the field. Detention at protests, temporary seizure of equipment, or the initiation of charges later dropped all fall within existing legal authority. Yet their cumulative effect mirrors the restraint the Court rejected. The process imposes costs on journalists while preserving the appearance of constitutional compliance. In this sense, enforcement becomes a substitute for censorship, achieving deterrence without confronting First Amendment doctrine directly.

Seen through this historical lens, the Don Lemon episode is not an aberration but an illustration of a mature enforcement model. It demonstrates how the state can respond to unfavorable visibility without formally suppressing speech. Courts may ultimately protect journalists after the fact, just as they did in 1971. But protection delayed is protection diluted. The lesson of the Pentagon Papers was that press freedom must operate at the moment of disclosure, not merely in retrospective vindication. When journalists are arrested for doing their work, even briefly, the constitutional harm lies not only in the individual incident but in the precedent it sets for future coverage of state power.

Why Courts Still Matter and Why They Are Not Enough

Courts remain essential guardians of press freedom precisely because they articulate limits that political actors are often unwilling to respect voluntarily. Decisions such as New York Times v. United States establish constitutional boundaries that prevent the most overt forms of suppression and affirm the principle that the press serves the public rather than the state. Judicial review provides a forum in which executive claims of necessity can be tested against evidence rather than accepted as assertion. In moments of crisis, this function is indispensable. Without courts, claims of national security would routinely override democratic accountability. In this sense, courts matter because they preserve the legal architecture of press freedom, maintaining a baseline protection against direct censorship and ensuring that prior restraint remains exceptional rather than normalized.

Yet the protective power of courts is inherently reactive. Judicial remedies occur after enforcement has already taken place, after journalists have been detained, equipment seized, or reporting disrupted. Litigation unfolds slowly, often long after the news cycle has passed and the chilling effect has already done its work. Even favorable rulings cannot fully restore what has been lost in the moment of suppression: access, momentum, and the confidence of sources. Courts may vindicate rights in principle, but they rarely erase the practical costs imposed by enforcement.

This temporal gap exposes a critical limitation. Constitutional doctrine is designed to address formal violations, not cumulative pressure. Arrests later dismissed, charges quietly dropped, or detentions deemed lawful under broad statutes may never trigger judicial scrutiny at all. As a result, enforcement-based intimidation can persist beneath the threshold of constitutional crisis. The law recognizes injury most clearly when speech is prohibited outright, but it struggles to address speech that is burdened, delayed, or discouraged through procedural means. Courts can declare principles, but they cannot easily police atmosphere, nor can they track the subtle behavioral shifts produced by repeated encounters with enforcement power.

Institutional imbalance further constrains judicial protection. The state possesses resources, discretion, and authority that journalists do not, and this asymmetry shapes outcomes long before any case reaches a courtroom. Legal defense requires time, money, and institutional backing, all of which influence editorial decision-making in advance. Smaller outlets, freelance reporters, and independent journalists are particularly vulnerable, as the cost of contesting enforcement may exceed their capacity to absorb it. Risk is distributed unevenly, and rights are exercised accordingly. Courts can equalize doctrine on paper, but they cannot equalize exposure, nor can they compensate for the deterrent effect of unequal power.

For these reasons, courts are necessary but insufficient. They remain a backstop against overt repression, but they cannot alone secure the conditions under which journalism can function freely and fearlessly. Press freedom depends not only on constitutional rulings, but on norms of restraint within law enforcement, professional solidarity among journalists, and sustained public recognition of journalism’s democratic role. When enforcement is used to manage visibility rather than punish crime, judicial protection arrives too late to prevent harm. The challenge is not to diminish the importance of courts, but to recognize their limits and to confront the broader systems of power that operate beyond their immediate reach.

From Prior Restraint to Managed Visibility

The evolution from formal prior restraint to managed visibility marks a fundamental shift in how state power interacts with journalism. After the Supreme Court foreclosed the most explicit forms of censorship in New York Times v. United States, the problem for government actors was no longer how to stop publication outright, but how to shape the conditions under which reporting occurs. Managed visibility achieves this goal by allowing journalism to exist while constraining its reach, timing, and intensity. Information is not banned, but it is made harder to gather, riskier to publish, and easier to marginalize. Visibility becomes conditional rather than absolute.

This model relies on a dispersal of pressure rather than a single act of suppression. Enforcement actions, surveillance, access control, credentialing, and legal ambiguity operate together to regulate exposure without announcing regulation as such. Journalists are permitted to report, but only within an environment saturated with friction, uncertainty, and procedural risk. The result is not silence, but distortion. Some stories arrive late, stripped of immediacy and impact. Others are truncated as access narrows or sources withdraw. Still others are never pursued at all because the cost of pursuit is too high to justify the institutional risk. Managed visibility functions as a filtering mechanism, shaping what enters public discourse not by prohibition, but by attrition and deterrence.

Crucially, managed visibility is compatible with democratic rhetoric. Because courts are not asked to enjoin publication, and because journalists are rarely convicted for their work, institutions can claim fidelity to press freedom even as its practical exercise narrows. This accommodation allows enforcement-based control to persist across administrations and ideological shifts. It does not depend on authoritarian impulse or overt hostility to the press. It depends instead on administrative habit and risk management. The press is tolerated so long as it does not disrupt too forcefully, too persistently, or too visibly the operations of state power.

Understanding this transition clarifies why historical victories like the Pentagon Papers case remain relevant but incomplete. The rejection of prior restraint established an essential constitutional boundary, but it did not guarantee the conditions necessary for fearless journalism. Managed visibility occupies the space between law and practice, where freedom exists formally but erodes functionally through accumulated pressure rather than explicit command. The challenge for press freedom in the present is not only to defend against censorship, but to recognize and resist the quieter systems that regulate exposure without forbidding it. The Constitution may prohibit restraint, but democracy depends on more than permission. It depends on the practical ability to see, to linger, and to report without fear of being managed out of relevance.

Conclusion: The Pentagon Papers in an Age of Handcuffs

The lesson of the Pentagon Papers was not merely that the press prevailed in a landmark Supreme Court case, but that the state revealed the depth of its anxiety about exposure when its credibility was placed at risk. New York Times v. United States demonstrated that when journalism threatens to puncture official narratives, power responds first with claims of necessity and urgency and only later, if forced, with constitutional concession. The Nixon administration’s insistence that publication would endanger national security masked a deeper concern about loss of control over public understanding of the Vietnam War. The Court’s rejection of prior restraint affirmed a crucial principle: fear of embarrassment, loss of authority, or political fallout could not justify silencing the press in advance. Yet the history traced in this essay shows that the constitutional boundary drawn in 1971 did not dissolve the underlying impulse to manage visibility. It redirected it into forms less visible, more defensible, and harder to challenge.

In the decades since, the tools have changed while the objective has remained remarkably stable. Injunctions have given way to arrests, surveillance, access control, and procedural harassment deployed at moments of maximum sensitivity. Journalists are no longer halted by court order before publication, but they are increasingly confronted in the field, at protests, borders, and federal operations, where enforcement discretion is broad and accountability diffuse. Handcuffs replace injunctions not because they are legally equivalent, but because they are functionally effective. They interrupt reporting in real time, impose personal and institutional cost, and communicate risk to others watching closely. Crucially, they do so without forcing courts to confront the doctrine of prior restraint directly, preserving the appearance of constitutional fidelity while narrowing the space in which journalism can safely operate.

This evolution matters because it reveals how constitutional protections can coexist with practical erosion. The press may retain formal freedom while losing the conditions necessary to exercise it fully. Courts continue to matter, and judicial victories remain vital, but they often arrive after the moment of greatest harm has passed. The Pentagon Papers were published despite government resistance. Modern journalists are increasingly asked to decide whether publication is worth the personal and institutional risk before they ever reach that point. This shift relocates the burden of constitutional conflict from the state to the press itself.

The enduring significance of the Pentagon Papers lies not only in what the Court forbade, but in what history teaches about adaptation. Democracies do not abandon repression; they refine it. Press freedom survives not because power relinquishes control, but because it is contested continuously across changing legal and institutional terrain. In an age of handcuffs rather than injunctions, the central question remains the same as it was in 1971: whether the public will tolerate a system in which visibility is managed rather than denied. The Constitution may prohibit prior restraint, but the health of a democracy depends on whether journalism can still operate without fear when the state most wishes it would not.

Bibliography

- Altschuler, Bruce E. “Is the Pentagon Papers Case Relevant in the Age of WikiLeaks?” Political Science Quarterly 130:3 (2015): 401-423.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1970.

- Black, Hugo L. “The Bill of Rights.” New York University Law Review 35 (1960): 865–881.

- Bollinger, Lee C. Uninhibited, Robust, and Wide-Open: A Free Press for a New Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Cole, David, and James X. Dempsey. Terrorism and the Constitution: Sacrificing Civil Liberties in the Name of National Security. New York: The New Press, 2006.

- Earl, Jennifer, Thomas V. Maher, and Jennifer Pan. “The Digital Repression of Social Movements, Protest, and Activism: A Synthetic Review.” Science Advances 8:10 (2022): 1-15.

- Ellsberg, Daniel. Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Viking, 2002.

- Moscati, Ivan and Carlo Zappia. “Between Worlds: Daniel Ellsberg (1931-2023).” Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics 17:1 (2024): 364-377.

- New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971).

- Sheehan, Neil, Hedrick Smith, E. W. Kenworthy, and Fox Butterfield. The Pentagon Papers. New York: Bantam Books, 1971.

- Stewart, Potter. “Or of the Press.” Hastings Law Journal 26 (1975): 631–636.

- Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- United States Congress. United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1971.

- United States Department of Defense. History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1971.

- U.S. Department of Justice. Report on Investigations of Unauthorized Disclosures. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, various years.

Originally published by Brewminate, 04.14.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.