Possible sources for propaganda messages appearing on gems in the Middle and Late Roman Republic.

By Dr. Paweł Gołyźniak

Department of Classical Archaeology

Institute of Archeology

Jagiellonian University

Introduction

It is difficult to put the beginnings of advertising oneself through Roman Republican engraved gems and their other political applications into a precise chronological framework, let alone put a date to individual actions performed by their owners. The first use of intaglios and cameos for political reasons, e.g. for propaganda, is traditionally associated with Lucius Cornelius Sulla (c. 138-78 BC).1 This is indeed the first moment, attested by both archaeological and literary sources, when a Roman political leader deliberately used a propagandistic motif commemorating his victory over an opponent for his personal seal (cf. chapter 7.1.1). However, there is some evidence suggesting that the first occurrences of gems being used for self-promotion are much older. For example, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus is said to have used a seal depicting Victory with a palm branch.2 According to investigations on the private seals of prominent Roman politicians presented in the next chapters, it is evident that figures such as Barbatus chose the subjects for their seals because of their special relevance; they always commemorated important moments of their careers or praised their particular qualities (cf. chapters 7.1.1, 8.1.4, 8.2.3, 9.3.1.3 and 10.3). For this reason, Victory with a palm branch on Barbatus’ seal was surely intentionally chosen to immortalise his victory over the Etruscans near Volterra in 298 BC. Pliny informing us about the first use of rings by Roman nobiles makes it explicit that about 305 BC rings (supposedly with gems) were used only by a few which makes them objects of social distinction and markers of a privileged class.3 Before I present undoubted applications of intaglios and cameos for self-advertisement and propaganda in the 1st century BC, we should consider what factors contributed to the later frequent use of gems for these purposes. It is necessary to investigate whether there were any signs of such actions already in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.4 For the development of gems’ employment in propaganda can be described as an evolutionary model starting in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC to the fully-expanded machinery in Augustus’ reign. In this chapter I focus on the analysis of possible sources for propaganda messages appearing on gems or actions performed through or with them in the period of the Middle and Late Roman Republic.

It has been a common practice to distinguish etruscanising and hellenising sub-types of Roman Republican gems, mostly due to their forms, styles and subject-matter.5 However, more recent studies reveal the increasing importance of the central-Italic and south-Italic elements.6 Local components were strongly influenced by the impulses coming from outside: Etruria from the north and Greece from the south and east. One of the links between all of them was self-presentation, a phenomenon practiced on gems by the Etruscans, Romans, Italics and Greeks alike. However, regional diversity is reflected not only in the abundance of styles and fashions performed by gem engravers throughout the 3rd and 2nd century BC,7 but also applications of gems for activities that were unique for the aforementioned cultural elements. Bearing this in mind, but also trying to simplify the whole mechanism, I believe it is best to propose three basic traditions which in various ways made gems attractive propaganda tools in the Roman Republic and under Augustus:

- Etruscan and Italic tradition involving aspects of self-presentation;

- Hellenistic tradition mostly based on the royal activities but also introducing new forms of gems (cameos, cameo vessels, works in the round) and

- Roman tradition basically promoting the state with its institutions and political leaders as well as families and their legendary origins and various customs.

All three were intertwined during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC and they ultimately merged into one system in the 1st century BC that indeed elevated many types of gems to the role of propaganda transmitters.8

Etruscan and Italic Tradition (Self-Presentation)

The recent research on late Etruscan and Italic glyptics revealed much new data regarding the use of engraved gems in Italy at the turn of the 4th and 3rd century BC. It appears that one of the main reasons for carrying a finger ring with a specific device was self-presentation.9 In fact, about 60% of Etruscan and a globolo scarabs fulfilled this particular function.10 This activity, as understood here, focuses on expressing oneself in a positive way through specific images in order to identify with the virtues and ideas which were shared and appreciated by the community the individual belonged to. Taking a closer look, self-presentation is just one small step from propaganda, which also aims to present the propagandist in the best way possible, however, with a clear intention of influencing or making an impression on others. Self-presentation and propaganda are two very closely related communication techniques. Even though self-presentation covers many more aspects of the glyptic repertoire than propaganda, it is a source for self-presentation and personal branding that later became the most popular propaganda practices in use on gems. For this reason, it is necessary to comment briefly on self-presentation on gems practiced first by Etruscans and Italics that was later successfully adopted by the Romans.

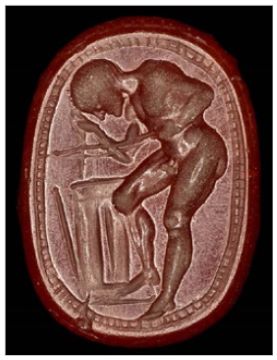

Regarding late Etruscan-early Italic glyptics, Hansson distinguishes five basic areas of gems’ devices relating to the concept of self-presentation: athleticism, hunting, warfare, banqueting (symposium) and religious acts (sacrificing).11 Each of these subjects was meant to express a virtue, value or quality appreciated within the society the individual lived in. Therefore, representations of athletes at various activities like running, jumping, throwing the discus as well as cleaning the body and even standing by a luterion and washing hair or groups of chariot drivers if engraved upon the gemstones should be usually understood as a self-presentation practice (cat. nos 6.1-2, Figure 1).12 Physical training was a crucial preparatory stage for entering military service. For young males who wished to pursue such a career, it could be of importance to highlight their physical prowess by putting an image related to this virtue upon their ring. Such an act would reflect their talents.13

Another social activity related to the same quality is hunting. Both, Etruscan and a globolo scarabs are full of images related to this particular enterprise. It seems reserved for a few, since hunting played a central role in the social training of aristocratic youths, but the glyptic material yields less elaborate representations of hunters. Even simple devices showing hares, hounds or stags might refer to hunting as an activity involving cleverness, flair, physical strength and endurance (cat. nos 6.3-4, Figure 2). Understood as such, hunting images would have reflected those positive qualities of gems’ owners.14

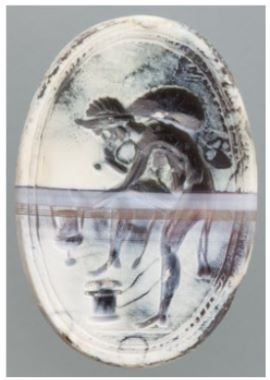

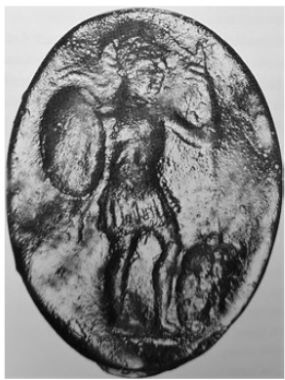

The subject-matters related to warfare, understood in a broad sense, are extremely popular on Etruscan and Italic scarabs. Representations of generic warriors and heroes who are often undistinguishable, unidentifiable Greek heroes (especially Achilles, Heracles and so on) as well as horse and chariot riders either represented as single figures, in pairs and other groups belong to this category (cat. nos 6.5-6, Figure 3). They would have been suitable for a young man entering his military career as well as for those proud of their military prowess and skills.15 Moreover, those who served a particular military unit might have wanted to highlight being a part of it by using an image testifying that. On the other hand, Greek heroes could have served as examples to follow, especially for those young military men may have received gems with such a depiction upon entering military service.16

The next class of representations related to self-presentation is that referring to the world of the symposium. Satyrs and other members of Dionysus’ thiasos as well as various winged creatures and depictions of Eros are not frequent, but still, may refer to the symposium as an activity performed by the aristocracy (cat. nos 6.7-8, Figure 4). Such a distinction and highlighting of social status would count as self-presentation. This category in particular informs us about the growing influence of the Greeks on the lifestyles and cultural practices of the people living in southern and central Italy.17

The last group of representations connected to expressing yourself are religious scenes of people engaged in sacrificing animals to the gods and performing other religious practices. These may refer to the priests, haruspices, augurs and other important religious offices that enjoyed widespread respect within society (cat. no. 6.9, Figure 5).18 Since the status of these people was highly important, they wanted to mark it in some way, and it is presumed that carrying a ring with symbols of the augurate or any other religious office was reserved only for the few. This kind of self-presentation might have had some powerful consequences because once marked, a priest enjoyed privileges and special treatment among members of the society he lived in.

Hansson mentions one more group of representations that in my opinion counts as self-presentation. These are images showing male and female figures engaged in various activities that might be understood as their occupations and crafts. It is easy to imagine that a skilful potter, ironsmith or even a gem engraver was proud to present (maybe even himself directly) his occupation or profession upon a ring (cat. no. 6.10, Figure 6).19 Just as with the groups mentioned above, here a link between real life and mythology is visible too since representations of Daedalus, the Argonauts or Vulcan at work were popular as well and might have referred to a craft in general as a form of important activity contributing to the development of the whole society. On the other hand, gems presenting such subjects served for self-advertisement.

The whole concept of self-presentation through gems had been adopted by the Romans from the Etruscans and Italics already in the 3rd century BC and was one of the most important mechanisms driving glyptic production also in the following centuries. Roman Republican glyptics is usually roughly dated to the 3rd-1st centuries BC and among gems manufactured in this period, one easily identifies the same thematic groups as distinguished above.20 They refer to the same aspect of self-presentation as in the Etruscan and Italic material.

Regarding the world of sports and games, representations of athletes engaged in various kinds of activities reflecting the athletic virtues and physical prowess are common (cat. no. 6.11, Figure 7). Gems with such devices constitute a significant group and they surely were meant to be taken as self-presentation. In contrast to the Etruscan and Italic glyptics, mythic references in this category of gems are less frequent, though. Such heroes as Tydeus and Peleus, who used to be appreciated for their physical prowess and were thus linked with athletics, are not so popular anymore.21 This is probably due to the advanced secularisation of this theme which was associated mainly with the human sphere in the 3rd to 1st centuries BC.

Hunting, so popular on Etruscan and Italic gems is also fairly common on Roman Republican gems. Likewise, basically two subcategories can be distinguished: figural representations usually involving a hunter, his prey (birds, hares and so on) and companion like a hound or a sole animal study (stag, hound, hare etc.) which is a shortcut of the hunting motif in general (cat. no. 6.12, Figure 8). Among the mythical images related to this activity, depictions of Artemis with her stag or hound, and Actaeon devoured by his own dogs appear, but these subjects are less likely to be related to self-presentation.

Concerning warfare, the Romans adopted not only the whole concept of self-presentation through putting a warrior or heroic image upon their rings, but they also did so regarding hatched border decoration and stylistic elements.22 This is especially true of the early 3rd century BC, however, the situation is much more complex from the late 3rd centuries BC onwards. The tradition of engraving gems with images of warriors, heroic warriors and identifiable Greek heroes continues down to the 1st century BC and even beyond (cat. nos 6.13-38, Figures 9-14).23 The motivations for their use were in principle the same as the Etruscans and Italics. Greek heroes were regarded as exempla virtutis by gems’ owners,24 however, more emphasis is gradually put on the careers of individuals as well as on the praise of spectacular achievements. Pliny sheds some light on the reasons why Romans often chose this kind of iconography. In his Natural History he writes that ‘Intercatia, whose father challenged Scipio Aemilianus, and was slain by him, was in the habit of using a signet with a representation of this combat engraved upon it.’25 Gems presenting multi-figured compositions of warriors in combat could commemorate a particularly important duel or event related to the military career of a certain Roman, sometimes including mythological references (no. 6.26, Figure 12). The rarely occurring inscriptions help to determine objects’ functions as well as their potential value in self-advertisement.

The majority of inscriptions refer to gem sitter’s name and apparently create a special bond between him and the figure represented upon the intaglio (cat. no. 6.37, Figure 13). This is self-presentation in the clearest way possible often combined with a comparison to a mythological or even divine patron. However, a sardonyx from Hannover engraved with an image of a naked warrior with a spear and shield, bears an inscription (EYTYKI – ‘good luck!’) that should be read as on the stone (cat. no. 6.24, Figure 14). It suggests that some of the gems in question were regarded as amulets bringing good luck in combat and war. Apart from these, in the period spanning from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC, representations of horse riders were particularly common, and they possibly referred to self-presentation too, especially where the class of equites is concerned since only its members had the right to wear a gold signet ring and a representation of a horse rider upon such a ring was a synonym for equestrian status (cat. nos 6.39-58, Figures 15-16).26 Some of the types might stem from Hellenistic culture, though and thus, their meaning remains obscure unless they reproduce, for instance, equestrian statues.27

To sum up, the whole phenomenon was gradually transformed into bolder private allusions and exploitation of these images changed its focus from the person represented on a gem to the one who carried it. As a result, in the course of the 1st century BC, many propagandists not only made references to specific mythological figures, but even identified with them (cf. chapters 7.1.5, 7.2.4, 8.1.9, 8.2.8, 9.1.7, 9.2.6, 9.3.1.8, 9.3.2.7 and 10.7). Like earlier Etruscan and Italic gems, Roman Republican ones bearing subjects related to warfare were used by those who served in particular units or who experienced brotherhood in arms. They might have wanted to exhibit their affiliation to such units which was a kind of proclamation of membership. It was later exploited by various political factions as it was a common habit to make public one’s political affiliation during the 1st century Civil Wars (cf. chapters 8.1.5, 8.2.4, 8.2.6, 9.1.3, 9.1.5, 9.2.2, 9.2.4, 9.3.1.4, 9.3.1.6, 9.3.2.3, 9.3.2.5 and 10.4). Alongside all these motifs appear images that I identify as presenting Roman generals, imperators, dictators and high rank officers. These cannot be regarded as ordinary pieces just relating to self-presentation, but they are first manifestation of propaganda on gems and seem to be purely Roman creations. They are therefore discussed separately (cf. chapter 6.3.3). Finally, it should be kept in mind that in the period discussed, many depictions of warfare could have been used for different reasons than I have outlined above. For instance, Greek heroes were preferable on gems because they were legendary founders of numerous Italian cities, especially those located in the southern Italy.28 It seems that a sort of local patriotism of the Romans might have contributed to the popularity of such images too. Some of them also were used as family symbols (cf. chapters 6.3.1, 7.4.2 and 8.3.3). Overall, a general observation is that there are many more representations of Greek heroes and warriors on Roman Republican gems than before because Roman society was much more militarised than the Etruscan and Italic ones.29

Subjects referring to banqueting (symposium) constituted a significant group in Roman Republican glyptics. Depictions of satyrs, maenads, Dionysus, Eros – all of them are present in large quantities but should not be regarded as only related to self-presentation (cat. nos 6.59-60, Figure 17). Perhaps some of them were still seen as markers of high social status, but in fact, Roman culture was much more exposed to the Hellenistic influences and thus, the great popularity of dionysiac subjects may be explained as a reflection of that process. Moreover, these kinds of gems, surviving in great quantities, must have been used by the masses, not by a few, so their potential application to self-presentation was much weaker than before. Generic and dionysiac scenes had been especially popular in the 1st century BC also due to the particular political and cultural significance which will be further discussed (cf. chapter 10.8).

Religious acts such as sacrificing, rituals as well as symbols referring to religious offices are also present in Roman Republican glyptics. It goes without saying that these subjects were borrowed from Etruscans and Italics, but in some cases of the 1st century BC, it might be argued that they were produced for specific political leaders, especially if augural symbols are considered (cat. no. 6.61, Figure 18).30 Among the Roman Republican gems produced in the 3rd and 2nd century BC one finds several outstanding subjects. First of all, there are gems showing busts or heads of priests. In Berlin there is a brown glass gem presenting a pair of busts of priests with apices on the heads which is dated around 100 BC (cat. no. 6.62). Other glass gems show only one bust of an augur and are kept in a private collection and in Aquileia (cat. nos 6.63-64). A nicolo stone with an image of a Roman priest to the right wearing the tutulus, a close-fitting round cap, tied under the chin with strings (offendices) is preserved in London (cat. no. 6.66) and another nicolo in Udine features the same subject (cat. no. 6.65). There are also known some gems presenting priests in figural forms such as a sardonyx in Berlin engraved with an augur who steps to the left holding a lituus in his hands (cat. no. 6.67) or a prase showing a haruspex performing a ritual in St. Petersburg (cat. no. 6.68). All these gems confirm special social status of their sitters and could be used for self-presentation. This is indicated by the presence of such gems on later bronze statues. For instance, Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples preserves an outstanding bronze statue of emperor Tiberius depicted as chief priest of Rome wearing a veil over his head and a ring on his finger with a lituus engraved upon it.31 Another statue equipped with a ring with augural symbols is that of Augustus as a rider found in Cumae.32 These statues give us context for the use of gems with augural symbols. It is clear that they were used by the most important personalities in the history of Rome, so it seems reasonable to believe that they represented the special status of their owners in earlier times as well. Otherwise, they were simply tokens of their profession or employed for family propaganda (cf. chapter 6.3.1).

A peculiar group of intaglios are those depicting Roman generals and other officials performing rituals and various religious practices (offerings) as a part of war preparations or victory celebrations. For instance, in Pavia there is a nicolo presenting a victorious Roman general with two of his companions about to sacrifice a bull on an altar in front of them (cat. no. 6.69). Another interesting piece is in Paris and shows a Roman soldier or general sacrificing a bull to the god Mars standing to his left (cat. no. 6.70). Vollenweider suggested that this carnelian might have been related to the wars that Rome conducted in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC during the conquest of Italy and beyond.33 A highly interesting motif is that of a Samnite warrior making an offering (ver sacrum) with a bull before or after a battle with two other warriors in the field. It exists on several gems and probably is related to sacrifice made during the second Punic War (cat. no. 6.71, Figure 19).34 All those intaglios might have served as ritual objects, but it is tempting to perceive them as commemorating particularly important moments in Roman history, especially those related to the wars Rome was engaged in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. Commemoration of such events was an essential part of all promotional practices of propagandists and even though not numerous, all the gems mentioned here have outstanding quality of engraving and complex subject-matter. It may be concluded that they were intended to be used among higher social classes who would both appreciate them and understand the messages encoded on them.

Finally, crafts and professions were well covered in the Roman Republican material and just as with Etruscan and Italic glyptics, intaglios presenting various occupations and people at work should be linked with self-presentation but not necessarily directly (cat. nos 6.72-73, Figure 20).35

Summing up, self-presentation through engraved gems was successfully adopted by the Romans and widely used in the 3rd-1st centuries BC. According to Hansson, political and religious life is conspicuously absent from the, at least, a globolo material.36 This is due to the specific cultural and political context. A globolo gems, which in a very simplified way, can be described as Etrusco-Italic glyptic material produced between the late 4th and early 2nd centuries BC,37 illustrate that in this period, glyptics was much concerned with individuals. Even though as Hansson says, some general trends existed, it was always up to individuals to decide what kind of image they identify with and are eager to carry upon their rings. At first glance, Roman glyptics experienced the same phenomenon in the 3rd and early 2nd centuries BC. However, as shown above, the increasing number of military subjects, much stronger emphasis put on the gem owner and reflection of his particular merits, qualities and successes as well as the highlight of his special status within society was becoming more and more important as time passed. Ultimately, already in the 2nd century BC, but especially in the 1st century BC, politics had a much greater impact on gem devices than it had in the preceding centuries. Still, it can be said that while self-presentation through gems worked on a general level in the 3rd and 2nd centuries, in the course of the 1st century BC political leaders started to subordinate glyptic art to their personal goals, including propaganda campaigns. Glyptics was undergoing profound changes which are clearly noticeable not only in the repertoire of devices but also in their forms and scale of production (increasing number of glass gems, cameos, works in the round, vessels). Self-presentation borrowed from Etruscan and Italic glyptics was one of the pillars for those changes to occur. Multiple impulses originating from the Hellenistic culture that worked especially well in the late 3rd and 2nd centuries BC for Roman elites were another.

Hellenistic Influences

Overview

The second major source of inspiration for the Roman Republican gem engravers and politicians was Hellenistic culture. Like Etruscan and Italic glyptics, Hellenistic glyptics influenced Roman glyptic art to a considerable degree in terms of new forms (cameos, carved vessels, works in the round), practices (collecting, triumphal processions, royal patronage), styles, techniques and of course iconography. As has been proved by Hansson, Hellenistic archetypes started to mingle with glyptic production of the southern and central Italy as early as the mid-4th century BC.38 Because the archaeological and cultural context for the Roman Republican gems is largely incomplete, it is difficult to point out which depictions and practices stem from Hellenistic traditions unless one tries to trace them according to the political motivations that might have been the reasons for their adoption by the Romans.39

Portraits

The first category of glyptic material that experienced a massive Hellenistic impact is intaglios and in a later phase also cameos with human portraits. Although Vollenweider identified some Etruscan and later Italic and Roman Republican independent traditions regarding gem portraiture,40 it is a generally accepted view that the practice of putting an image of a living man upon a gem was a Greek invention that flourished in particular in the Hellenistic period (cat. nos 6.74-77, Figures 21-22).41 From Alexander the Great down to Cleopatra VII a number of portrait gems had been produced and their functions are the subject of fierce debate.42 These gems could have been used as personal seals of the rulers that commissioned them,43 but there is evidence that they were exchanged in a form of diplomatic gifts. For instance, Lucius Licinius Lucullus was offered a gold ring with an emerald engraved with a portrait of King Ptolemy IX Soter II during an audience at his court in 86 or 85 BC.44 According to Plutarch, Lucullus out of modesty, declined to accept the gift, but Ptolemy showed him that the engraving on it was a likeness of himself, so the Roman general accepted the gift wishing to make no offence to the king.45 As Plantzos observes, the passage offers valuable information for our understanding of royal portraiture in glyptic. It was regarded as a great personal honour to be offered an intaglio with an image of a ruler. This privilege was reserved for the few and could not be simply rejected.46 Furthermore, Gutzwiller argues that portrait gems were disseminated among royal supporters before coins.47 Literary records suggest that gems with portraits were also used in order to manifest loyalty and support for a political leader. Polybius, when talking about the murder of Ptolemy IV by Agathokles and his followers mentions a certain Aristomenes who expressed his support to Agathokles by being the first who used to wear his image on a ring.48 However, this phenomenon could have been double-sided. It is easy to imagine that it was a king who by giving a precious gift with his likeness engraved upon it (e.g. a ring with a gem) counted on loyalty of the gifted person.49 The confirmation of that comes from Athenaios who states that in the days of confusion and anarchy preceding the advent of Mithridates in Athens, the peripatetic philosopher Athenion, who became a dictator in the city in 89/88 BC, and was an active member of the pro-Pontic party, was seen wearing Mithridates’ portrait upon a ring.50 It is not clear from this narrative whether it was Mithridates who used to gift gems with his own portraits to his supporters or they commissioned such objects on their own, but the former supposition is supported by the fact that Mithridates was a collector of gems and hired the best gem engravers to work at his court (cf. chapter 6.2.2 below).

The situations described above clearly show that engraved gems were used for political and propaganda purposes in the Hellenistic world. They were employed as the personal seals of the rulers, commemorated specific events and were the means of manifestation of loyalty and support. But above all, gems with portraits in the Hellenistic period were used for personal branding and contributed to the dissemination of the royal image among the people, even if these were only limited groups.51 Besides, gems with portraits were exceptionally luxurious products testifying to the high social status and distinction of both their commissioners and receivers.52 It seems this was the main reason why in the course of the 2nd centuries BC many Roman dignitaries and generals visiting the East during military campaigns followed Hellenistic examples and started to have their portraits cut upon their rings. The superb quality of glyptic art and the prestige it gave was appealing for them. It is a common view that Etruscan art was quickly romanised by the aristocracy in Rome because it was top quality and allowed the user to stand out from others.53 The same applies to Hellenistic art that greatly influenced the Roman, especially after the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) (cf. above). Again, the dominant role was played by the aristocracy for which Hellenistic standards offered far more possibilities for fulfilling their needs and desires for raising their own popularity and authority. At the end of the Second Punic War, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (236-183 BC) emerged as the most significant Roman general and political leader. After the battle at Zama in 202 BC, Scipio was welcomed back to Rome in triumph with the agnomen of Africanus. He refused the many honours which the people would have thrust upon him such as consul for life and dictator. Instead, in the year 199 BC, Scipio was elected censor and for some years afterwards he lived quietly and took no part in politics. Nevertheless, his position was strong and there were many who sought his support and wanted to assure him of their loyalty. A substantial number of engraved gems and rings make one think that way.

The famous gold ring found in Capua engraved with a portrait of a Roman, who has been recognised as Scipio Africanus (cat. no. 6.78, Figure 23) is the most significant glyptic object relating to the Roman general.54 It is signed by a Greek artist, Herakleidas (AKAEIΔAC EΠOCI – Herakleidas made it) and is now preserved at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples.55 The portrait is presented in an entirely Greek manner, however, the style and the serious physiognomy including the thin, close-lipped mouth, is closer to the verist representations of the Romans praising contemporary ideals of gravity and piety. This piece is a good example of the situation when the commissioner must have been a Roman, while the artist was a Greek previously working somewhere in the Hellenistic East.56 It is a strange situation when the severe Roman standards are reflected upon an object that represents a major lapse in them since it must have been a precious, even boastful, item in character. We can only speculate if this ring once belonged to Scipio Africanus himself, but since the Romans adopted the same standards as Hellenistic rulers in patronising glyptic art and signed pieces seem to be direct commissions from the most wealthy and important people, such a possibility cannot be entirely rejected. One imagines that this was a mutually beneficial situation for the commissioner, who could boast of having his ring engraved by a famous artist, which brought him splendour, prestige and guaranteed him social distinction, and for the artist to claim one of his customers to be a prominent politician. The Herakleidas ring is dated c. 200 BC or slightly later and whether it indeed features a portrait of Scipio Africanus, it illustrates well the phenomenon of Hellenistic traditions in portraiture being developed by the Romans in glyptics.

In the case of Scipio Africanus his portraiture on gems appears to be not a single event, but a regular phenomenon. Vollenweider collected several glass gems that with greater or lesser probability portray the head of this famous Roman general (cat. nos 6.79-82). Several more can be added to this list (cat. nos 6.83-85, Figure 24).57 Portraits on all these gems are similar to bronze coins minted in Canusium in the early 2nd century BC58 as well as to the ring described above. Vollenweider pointed out two more rings which in her opinion present portraits of Scipio Africanus: a silver one now in London,59 and iron one in Louvre Museum in Paris,60 however, I think that considerable differences in both facial physiognomies and haircuts do not allow one to make such an attribution. In any case, except for one dark violet object in Berlin, all these gems are made of brown or yellowish-brown glass and have convex obverse sides, so they do indeed constitute a homogenous group. However, these portraits were not made from the same matrix and to my mind they exhibit differences in both facial features and coiffures. Therefore, it may seem speculative to regard them as portraits of Scipio Africanus, but the problems with their identification result from scanty comparative material and a range of skill on the part of the glass gems’ makers. It is certainly problematic to accept that they all copy one image engraved by Herakleides as Vollenweider proposed.61 Assuming that indeed these portrait gems were intended to represent Scipio Africanus, that they might have been produced for his followers who wanted to manifest their loyalty and commitment to him. Alternatively, some gem engravers took advantage of Scipio’s popularity in Rome and produced those objects for the market since there was a considerable demand for them.62 The six glass gems mentioned above probably were produced in Italy, possibly in Rome since they previously were parts of the Bergau, Fol and Stosch collections which were all created from the material originating from Italy (cf. chapter 11). The gem now in Athens could have been transferred there from Italy for instance by a Roman legionary. In conclusion, it is controversial to think that gems with portraits of Scipio Africanus were primarily used for the personal branding of that statesman. It is difficult to say whether Scipio indeed used the ring cut by Herakleides for his own promotion and commissioned it as there is no other evidence, either archaeological or literary, except for the ring itself. Nevertheless, the series of glass gems with his likeness must have resulted from his great popularity in Rome. It is possible that those gems were used for the manifestation of loyalty and support, especially among ordinary people rather than the aristocracy which would not have invested in cheap glass intaglios.

The portrait of Scipio Africanus cut by Herakleides is just one example, but in the course of the 2nd century BC personal branding on portrait gems was undertaken on a much larger scale. Furtwängler has pointed out that many representatives of Roman elites became fascinated by Greek culture and promoted themselves in a totally Hellenistic manner in glyptics.63 The contact with Graeco-Hellenistic civilisation was a crucial factor for some Romans deciding to have their portrait cut upon a gemstone. A proof of that is a garnet intaglio in Paris presenting the bust of a Roman in profile to the right with short curly hair and slight beard dressed in a chlamys (cat. no. 6.86, Figure 25). The gem is signed by a Greek artist Daidalos (ΔAIΔAΛOC). The person depicted has been identified as Titus Quinctius Flamininus (c. 229-174 BC).64 In the case of Scipio’s ring the Roman verism was quite straightforward, but here, the portrait is a bit idealised; Titus is projected as a relatively young man and his likeness is closer to the images of Hellenistic kings, rather than serious and rough images of Roman generals.65 In 197 BC he defeated Philipp V at Kynoskephalai which has been celebrated by several coin issues.66 It is likely that the gem in question was made in order to celebrate and commemorate this victory. Regarding coins, they exhibit some differences in style, which means they must have been prepared by several coin-die cutters, but it has been observed that Flamininus’ portraits from the gem and those coins were executed according to one concept – a combination of distinctive physiognomic features with an illustration of Titus’ famous philhellenism.67 Even though the work of Daidalos on stylistic grounds is entirely Hellenistic,68 the individualisation of the portrait means that it was cut for the personal use of the commissioner, in this case most likely Flamininus himself. This is also confirmed by the fact that he wears no diadem or laurel wreath on his head on the intaglio to manifest his role as the saviour of the people ruled by a tyrant as Flamininus with his army was asked by Greek and Asian allies to intervene against Philip. If he had paraded around with such an intaglio on his hand, he must have made a great impression on his peers. Again, one deals with a situation when a propagandist wanted to possess an extraordinary item cut by a top artist available which ideally presents him and reflects his values – in this case, also his appreciation for the Hellenistic culture. It is clear that this gem was a powerful propaganda tool since only such an individual as Flamininus could have afforded it both economically and ideologically. The gem is utterly exceptional like his gold staters struck in Chalcis c. 196 BC because before Flamininus almost no living person had been depicted upon coins as that privilege was reserved for deities.69 The gem was once a part of de Clercq and Count Boisgelin collections which encourages us to believe that it was cut in the East (Greece or Bithynia?), not in Rome.70

The third gem to provide evidence for increasing interest of the Romans in portraiture in glyptic art is a garnet intaglio in the collection of the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago (cat. no. 6.87).71 Like the preceding gems, this one bears a portrait of a powerful Roman individual, who has traditionally been identified as Mark Antony,72 however, this identification is incorrect. As Plantzos and Lapatin observe, this work is purely Hellenistic in terms of style. Besides, the gem’s form and material (highly convex garnet) as well as the heavy, gold ring with a stepped bezel it is set into suggest dating it around 150 BC.73 The piece is signed by a Greek artist Menophilos (MENOΦIΛOC EΠOIEI) about whom nothing certain is known, but he is likely to have worked in Asia Minor or on Delos.74 The portrait on the gem exhibits far-reaching individualisation reflected by strong jaw, sunken cheek, deeply cut mimic wrinkles, prominent nose and furrowed brow. His hair, although arranged freely is much shorter than on the previous two portraits. This illustrates the progressive adjustment of Greek engraving towards new Roman customers. The ring is said to have been found in Syria, and although this seems disputable,75 beyond a shadow of doubt it is an eastern product. The identification of the portrayed person is indeed problematic, but the gem is another example of a work made for a prominent Roman (possibly a general, diplomat or statesman?) who wanted to promote himself by commissioning a piece of extraordinary jewellery for himself. He might have paraded himself with a work executed by one of the best gem engravers of his times which gave him splendour and prestige as well as confirming his distinctive social status.

There are several other gems that combine the Hellenistic manner of engraving and stylistic features with Roman Republican individualisation of the portrayed person, the so-called verism aimed at a deep reflection of his personality.76 One such piece is a garnet intaglio from a private collection with a flat face engraved with a portrait of a man whose facial features and expression as well as the treatment of hair suggest him to be a Roman (cat. no. 6.88).77 According to the style, this gem should be dated to the late 2nd or early 1st centuries BC. There are two interesting mottled jasper intaglios cut with images of the Romans that may be broadly dated from the late 3rd to the early 1st century BC.78 The first one, housed in Berlin, is a double-faced scaraboid featuring a portrait of a sober and wrinkled man having short hair slightly receding at the temples and a Gorgoneion on the other side (cat. no. 6.89). Identification of this portrait appears particularly difficult. The Gorgoneion, as a single element, was usually employed on gems to avert all kinds of evil.79 If combined with a portrait, it would have meant the gem to be a personal amulet of the person depicted. However, giving the fact that the man presented on the gem in question seems a quite exceptional person and the object itself belongs to a rare class of early Roman portrait intaglios, it may be that the gorgoneion emblem is a later addition. It does not seem likely that the sign has a political reference anyway unless it testifies to identification with Alexander the Great.80 The second intaglio is now preserved in Paris and is also highly problematic in terms of the person’s identification, but it has been generally accepted that it represents a Roman statesman (cat. no. 6.90). This portrait can be compared to another mottled jasper intaglio presenting Philetaerus of Pergamon (c. 343-263 BC) now in London,81 and thus it is suggested that is was executed in Asia Minor.82 Another noteworthy piece is a garnet intaglio set in an ancient gold ring also housed in Paris (cat. no. 6.91). According to Vollenweider, it may portray a Roman ambassador and should be dated around 200-180 BC.83 It should be pointed out that this gem was a part of de Clercq and Count Boisgelin collections which suggests that it was indeed cut in the East (most likely Asia Minor), not in Rome. The next intriguing object is a bronze ring carrying a bust of a middle-aged man to the left also from the Paris collection (cat. no. 6.92).84 It can be roughly dated to the 3rd-2nd centuries BC but in my opinion identification of the person depicted as a Roman is not entirely convincing.85 Less problematic is a glass gem presenting a beardless Roman in profile to the right from London (cat. no. 6.93, Figure 26). The man wears a military cloak fibulated on the shoulder which suggests his role as a commander of the army. The object should be dated to the late 2nd or early 1st centuries BC and like other gems mentioned here, this one was meant to be used for personal branding, although, judging by the material used, it must have been made for a less prominent person. Finally, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston there are three intaglios of exceptional quality, executed in entirely a Hellenistic manner but portraying Romans (cat. nos 6.94-96, Figures 27-28). They all belong to the group described here and illustrate that the phenomenon of Roman portraits appearing on Hellenistic intaglios clearly intensified towards the 1st century BC.

In the course of the 1st century BC more and more Romans decided to have their portraits cut upon their rings and a general trend of adjusting the fashion of engraving towards the demands of these new customers is noticeable. Nevertheless, it must be stressed that all these evoked examples were purely Hellenistic creations. In most instances, the people presented on them cannot be identified but all of them are securely recognised as Romans who were generals and ambassadors visiting Asia Minor and other regions of the Near East during their diplomatic missions or military campaigns. They are responsible for the gradual adoption of Hellenistic traditions. The situation observed in glyptics reflects an increasing domination of Roman imperialism over the Greek East and gradual overtaking of artists who found their new customers among Roman dignitaries.86 Their commissions not only confirmed high social status, but also propagated successes and increased authority. This is confirmed by Pliny, who claimed that gold rings, which were regarded as special and informative of the exceptional status of their sitters within society, were worn by the Romans who visited the East.87 This is portrayed in the heavy Hellenistic rings that some of the gems mentioned above are still mounted. Yet, one must stress that in Hellenistic glyptics (3rd-2nd centuries BC) portraits of rulers and queens were cut in much larger quantities than those of Romans because they were meant to be delivered to many recipients and hence, should be regarded as personal branding activities.88 Only in the 1st century BC did portrait gems start to play a significant role in personal branding of the Romans. Earlier examples are not numerous which suggests that they were concerned with social distinction rather than the deliberate dissemination of the self-image among the wider audience.89 An exception seems to be gems with the portrait of Scipio Africanus, however, I believe that their relatively high number results from an ephemeral enthusiasm for this highly popular Roman general which was a bottom-up initiative rather than the result of his own enterprise (e.g. propaganda).

Patronage

The material collected above proves that in the course of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC Romans became patrons to gem engravers. This phenomenon is best illustrated by the works of Herakleides, Daidalos and Menophilos who we know for sure worked for Roman customers. This is hardly surprising since a good number of Hellenistic kings and rulers used the services of gem engravers and some are even believed to establish court workshops operating exclusively for them. Typically, Alexander the Great, reserved the right of cutting his own portrait upon ringstones only to one artist – the famous Pyrgoteles.90 The Ptolemies were keen patrons of glyptic art and employed such artists as Nikandros and Lykomedes.91 The gem engraver Sosis is attested to have been working first in Alexandria and then in Syracuse and similarly, Theokritos is believed to have worked in Sicily.92 The Seleucids also employed gem engravers at their court, for instance Apollonios worked for them.93 Mithridates VI Eupator (120-61 BC), who was a great admirer and keen collector of engraved gems as well as vessels made of precious stones, is believed to have organised a gem workshop at his court. It is believed that Apollophanes, Solon, Protarhos and Gnaeus all worked for him before they departured to Rome.94

These facts make us aware that glyptics was an exclusive and luxurious art and only a few could afford to use the services of the best engravers. Moreover, already in the late 3rd century BC the Romans started to imitate Hellenistic kings in their patronage over this peculiar art form and those who did so must have been highly appreciated among their peers for it confirmed their financial capabilities and compared them to kings. The art of gem engraving and the highly personal subjects, e.g. their sitters’ own portraits, were particularly appealing to ambitious Roman careerists. Naturally, their portraits lack of any attributes and are verist in terms of physiognomy and expression which was due to the values of modesty and piety obediently cherished by them, even though the art of gem engraving had little to do with those qualities at the time because of its luxurious character.95 It is evident that at this stage, employment of glyptic art in the self-presentation and propaganda activities of those first Roman military and political leaders was contributing to their social distinction, while forms and messages were less significant. The fact that an individual was an art patron and decided to have his portrait cut upon his ring already gained him recognition because in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC this was still very rare, even exceptional. A side effect of this process was the increasing influence of Hellenistic glyptics on Roman, which is easily observable in Roman Republican gems’ forms, styles and iconography (cf. chapter 6.2.5 below). Ultimately, the patronage of those few first Roman generals, diplomats and explorers of the East sparked a considerable phenomenon that resulted in the migration of Greek gem engravers from Alexandria and Asia Minor to Rome.96

Collecting

Another practice Roman elites adopted from Hellenistic kings was the collecting of engraved gems. Only very few could have afforded to spend vast sums of money on carved precious and semi-precious stones, therefore, in the Hellenistic world this kind of activity was reserved notably for the rulers and perhaps their wives. Mithridates VI Eupator is probably the most famous gem collector among Hellenistic kings, sometimes even recognised as the first one in the history.97 He is said to have possessed two thousand engraved gems and vessels decorated with precious stones.98 Moreover, his dactyliotheca was brought to Rome by Pompey the Great, exhibited during his triumph in 61 BC and ultimately dedicated to the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill.99 Similarly, Julius Caesar placed his six dactyliothecae in the Temple of Venus Genetrix on his Forum and one wonders if he exported some gems from the treasury of the Ptolemies while on his visit to Alexandria?100 It is debatable if the Ptolemies indeed owned collections of engraved gems, even though the Alexandrian court appears a natural place for such cabinets.101 As stated above, the Ptolemies, Seleucids and other Hellenistic kings employed top gem engravers at their courts, hence, it seems straightforwardly justified to think that at least a part of their production was kept in royal treasuries. A small proof for that is a record in Suetonius who informs us that even modest Octavian did not hesitate to take one precious object from the Ptolemies’ treasury after the battle of Actium – a murrhine bowl.102 Seleucus XII of Syria is reported to be a collector of gems on the basis of Pliny’s record and the fact that he possessed books and manuscripts on engraved gemstones.103 Apparently, some rulers enjoyed collecting and studying engraved gems as a hobby. For instance, Juba II was believed to have written a manuscript on gems and he was greatly appreciated by Pliny, even quoted by him in his Historia Naturalis book 37 devoted to gemstones.104

As will be described below (cf. chapters 8.1.2, 8.2.1, 8.3.1, 9.3.2 and 10.1), Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, Pompey the Great, Julius Caesar, Marcellus – all of these prominent Romans owned gem cabinets that usually were based on the collections created earlier by Hellenistic kings. The ownership of a considerable set of engraved precious stones and vessels was appealing to the Romans as it guaranteed social distinction and therefore, they continued the Hellenistic tradition of collecting. Moreover, in the second half of the 1st century BC there is a dramatic rise in the production of glass gems which is possibly a result of either a considerable engagement of the Romans in political affairs or collecting of intaglios and cameos at the same time. However, as it will be shown, in the case of the famous dactyliothecae these assemblages not only raised the authority of their owners and confirmed high social status, but also could be used for clever propaganda moves if dedicated to the temples and thus, became goods serving a common cause of the people of Rome, at least theoretically.

Triumphs and Processions

As far as glyptic art is concerned, there is one more royal practice of purely Hellenistic nature and origin that Romans have adopted. Engraved gems played a significant role in triumphs as recorded by ancient writers. Already Ptolemy II exhibited gems, vessels made of precious stones and other luxury objects encrusted with them in his famous procession in honour of Dionysus in the early 3rd century BC.105 Pompey the Great followed his example. After his victory over Mithridates VI Eupator, in 61 BC he organised a triumph during which he exhibited gems and vessels taken over from the king of Pontus.106 There is no direct proof for other Romans doing the same as Pompey. Exhibiting of gems during processions and triumphs added much splendour to the ruler or in the case of Pompey, a statesman and propagandist.

It must have been influential since Pliny recorded this event in his book as a pivotal moment for mass-production of engraved gems in Rome.107 Pompey not only initiated a fashion in Rome for possessing rings with engraved gems, but most importantly he made himself more recognisable and popular by exhibiting of the gems he brought to Rome as spolia of war so that the ancient writer immortalised his achievements in this respect.

Iconography, Forms, and Style

Finally, the last matter in the discussion on the impact of Hellenistic glyptics on Roman Republican gems and their potential political applications are iconography, forms and styles native to the East and transplanted to Rome. This is a broad issue that deserves a separate study and because it is not closely related to the main concept of this work, I would like only to single out some basic points. Due to long-lasting presence of the Greeks in Sicily and southern Italy, Roman Republican gems were strongly influenced by their Greek counterparts since the very beginning.108 One even points to a distinctive Hellenistic-Roman style in carving gemstones that flourished already in the 2nd century BC.109 As has been proved above, over the 3rd and 2nd centuries the Romans were increasingly interested in promoting themselves through the portrait gems, employment of gem engravers, collecting etc. basically imitating the actions performed by Hellenistic kings. These beginnings of Roman patronage over Greek gem engravers resulted in their influx to Italy and consequently, the stimulation of local styles and traditions by the eastern ones. In the 1st century BC a good number of engravers transferred their business from the East to Rome.110

Because of the Roman conquest of the East, many Hellenistic gems reached Rome and Italy either in the form of whole collections and individual pieces. Of course, this was not a single event, but a gradual process. Alongside this, some themes and ideas previously used specifically for Hellenistic intaglios and cameos also became popular in Italy. A good illustration of this process is the representation of a bust or head of Galene-Selene, which was widely popular on Hellenistic gems and it was due to Quintus Crepereius Rocus that the subject also become popular on Roman Republican gems as the moneyer employed it as his coin emblem.111 As Crawford writes, the moneyer was connected with the Roman negotiores in the Greek East therefore the Galene-Selene subject as well as other marine ones used by him as control-marks are suitable for a person with such a background.112 This example clearly shows the direct transfer of Hellenistic ideas and iconography to the Roman ground. There were many more Hellenistic themes that became widely popular on Roman Republican gems, especially bacchic and maritime themes.113 Also in terms of composition and techniques, borrowings from Hellenistic glyptics are clear. For example, the three-quarter view from behind, naked busts of deities and mortal women and many more had been absorbed.114 Finally, new forms such as cameos, carved vessels and small works in the round which were all Hellenistic inventions became popular especially under Augustus as will be presented below (cf. chapters 9.3.1.9, 9.3.2.9 and 10.9).115

Roman Tradition (Family Symbols, Personal Branding, Commemoration, and State Propaganda

Overview

Two main external directions influencing the development of Roman Republican engraved gems in terms of their political applications have been discussed above. Both, Etrusco-Italic and Hellenistic cultures made a great impact on propagandistic actions performed by Roman statesmen especially self-advertisement and personal branding. However, the native Roman element was an important factor in the development of propaganda on gems too. Below is presented a survey of themes that in the course of time became inspirational for later propaganda messages appearing on gems or were directly transformed into such. It is combined with a critical evaluation of the ideas proposed by other scholars. Most of the examples date to the period of the 3rd-2nd centuries BC but some may span the early 1st century BC too. All of them appear to be not a regular production, which is well documented for the later 1st century BC, but they are rather first attempts and experiments. Most of the examples refer to self-presentation practices aimed at showing oneself in a positive way with the highlight of particular merits, values and virtues. Some of them refer to the commemoration of military victories and other important events as well as to personal branding. This sub-chapter also offers a discussion on a poorly researched issue of family promotion through symbolism on gems. Finally, some of the gems presented here touch a broader issue of state propaganda which links to the ideas of romanisation and Roman imperialism spreading throughout the Mediterranean basin.

Family Symbols and References to Familial Stories on Gems

Family symbols, either understood as single items or their configurations and narrative scenes referring to the history, stories or legends of specific gentes were commonly depicted on coins of the Roman Republic issued by triumviri monetales.116 They used to promote themselves, their clan and its members in order to become more recognisable and raise authority by its transfer from legendary and historical ancestors. Such references made it clear that a person using them belonged to a small and distinctive community who often enjoyed special social status. Since engraved gems are strictly private objects, it seems natural to think that they should play the same or an even more important role in the display of family allegiances.117 Already by the end of the 19th century Furtwängler noticed a great potential in comparisons made between gems and coins in terms of promotion of gentes.118 However, a careful survey on the motifs that may refer to family propaganda on gems shows that overinterpretations are common and in fact to prove that promotion of the gentes and exhibition of membership to a specific family indeed occurred on gems is somewhat problematic. This is clearly noticeable in the case of the late Etrusco-Italic a globolo material as suggested by Hansson.119

We shall start investigations on the issue from analysis of the literary sources. They deliver some evidence supporting the view of the existence of family seals. One of the ancient writers who vaguely mentions them is Pliny the Elder. He does not inform when exactly Romans started to use rings with family seals or to make references to their ancestors with the use of gems, but as far as it can be judged from his Natural History book 37, this happened in the late 4th or early 3rd century BC.120 Beyond the shadow of a doubt, family seals were important, and it was a great honour to carry them upon one’s ring. They were passed from one generation to another.121 As Valerius Maximus informs, young Lucius Scipio disgraced himself by coming to an election in a soiled toga and thus his relatives removed the ring with the head of his father Scipio Africanus from his hand.122 It is clear that he inherited it, but even minor offences could be the cause of losing it which was considered a great shame and could literary ruin young Scipio’s career. A family ring belonged to pater familias and was given to a successor or adopted son, like in the case of Julius Caesar and Octavian (cf. chapter 9.3.1.1).123 Pliny suggests that after Augustus, all Roman emperors used as their official seal the ring with Augustus’ portrait engraved upon a gem by Dioscurides.124 Nevertheless, the record from Cassius Dio’s Historia Romana on the seal of emperor Galba is of special importance here as well because when he became the emperor he still used his family ring with an image of a dog standing on a prow rather than the portrait of Augustus (cat. nos 6.97-98, Figure 29).125

Actually, this is the only one example recorded when it is clear that a ring device was employed as a family symbol, even though it seems to have been used by more than one family.126 In any other cases, portraits of famous ancestors or deliberately created images were used to promote family through gems as in the case of Lucius Licinius Lucullus, Pompey the Great, Julius Caesar, Sextus Pompey and Augustus (cf. chapters 7.3.3, 8.1.6, 8.2.5, 9.1.4, 9.3.1.1, 9.3.1.5, 9.3.2.4 and 10.10). For this reason, it is extremely difficult to find any other family symbols employed in glyptics to be utterly convincing. Nevertheless, some attempts should be made and discussed as possible rather than completely ignored. Generally speaking, there are two categories of representations which could be of significance for family propaganda on gems. The first one consists of single symbols or their configurations. In coinage it was a common practice to form a kind of a symbolic rebus that would refer to the name of the issuer and his family. One wonders if in the case of engraved gems, the same phenomenon occurs. Some examples can be positively identified if compared to coins unless the symbols or scenes they bear have other precise and distinctive meaning in terms of glyptics, which is often the case. The second category encompasses various mythological and historical scenes so often appearing on intaglios. It is a well attested view to think that Roman gentes used highly sophisticated methods for their family promotion which often hides behind mythological and historical references.127 As will be shown, it is difficult to detect and correctly identify those on gems because such themes might have served for different purposes as well. Yet, some positive results of my investigations are presented below. The earliest applications of gems for family and origo promotion date to the second half of the 2nd century BC and this is consistent with observations made by numismatists regarding Roman Republican coinage.128 This correlation covers not only chronological framework, but also iconography and while comparing gems’ and coins’ devices one encounters some representations occurring in both media, probably at the same time.129 This is particularly helpful for stating that not only political leaders of the main factiones used to promote themselves on gems but also the less prominent ones as well as whole families or their specific branches (cf. chapters 7.4.2 and 8.3.3).

Regarding potential family symbols on gems dated to the 2nd century BC, the first group consist of individual symbols. The bull as a single motif exists on Roman Republican gems from at least 2nd century BC onwards and is usually understood as the astrological sign of Taurus.130 However, a peculiar type seems to occur on some gems where the animal is charging with raised hooves (cat. no. 6.99, Figure 30). This design is mirrored on or from the denarius of L. Thorius Balbus issued in 105 BC (Figure 31).131 Crawford as well as Campagnolo and Fallani argue that the motif may be a word-game corresponding to moneyer’s name rather than a reference to Juno Sospita appearing on the obverse side, which would further suggest the gems with similar device were used by the members of gens Thoria.132 However, the bull belonging to cattle may also be linked to the concept of Italy as a homeland and giving the year when the coin was minted it possibly recalls Roman common case facing the peril of the Cimbri invasion and Battle of Arausio where two Roman armies were destroyed.133 Perhaps the gems and the coin combine both elements suggesting input of the family Thoria into the defence against the invaders.

The head of Diana of Ephesus appears on the denarii of the Aemilian family in the end of the 2nd century BC and is regarded as the emblem of that gens.134 Perhaps some gems featuring the same motif were used as personal seals by the members of the Aemilian family, but there are no direct proofs for that (cat. nos 6.100-102, Figure 32). The fact that the head of Diana of Ephesus appears later on the coins issued by P. Accoleivs Lariscolus makes the hypothesis of taking her as Aemilian family’s emblem even weaker and in some other cases her image suggests the particular coins were minted in Asia Minor.135 Besides, according to some versions of mythological foundations of Rome, Aemylos, brother of Ascanius/Iulus was the eponymous ancestor of the patrician Aemilii but his images are absent in Roman Republican glyptics, or at least remain unidentifiable.136

The second type of representations that could be regarded as family emblems are figural scenes referring to mythology and legendary history of many gentes. A good number of historical, legendary, mythological and divine figures served Roman families as their ancestors or patrons at least. It seems justified to start this survey with Heracles who was said to have been ancestor primarily of the Fabia and Antonia as well as Potitia and Pinaria gentes.137 According to legend, the Fabii claimed descent from Heracles, who visited Italy a generation before the Trojan War broke out, and from Evander, his host.138 They were involved in the cult of Heracles and minted coins with his images.139 They used to put the head of the hero on their early coin types,140 while later his full figure engaged in various activities.141 The Pinarii and Potitii were connected with Heracles’ visit to Evander too, while the Antonii descended from a son of Heracles called Anton.142 Full-figure studies of Heracles are common motifs on engraved gems in the Roman Republican period (cat. nos 6.103-107, Figure 33), whereas heads of the hero were especially popular in the 1st century BC (cat. nos 6.108-109, Figure 34a-b). At first glance there seem to be plenty of motifs that would be suitable for seals of families claiming descent from Heracles. However, there is little direct evidence to think that Heracles was indeed used as a family symbol on engraved gems prior to Mark Antony’s references to his own legendary ancestry (cf. chapter 9.3.2.7). Heracles’ popularity on gems in the Roman Republican period is due to many reasons. One of them is the fact that several place names in Italy were connected to his adventures.143 Moreover, vitulia as a name for the Italian peninsula supposedly came into usage because Heracles chased a runaway bullock (vitulus) there.144 It is reasonable to think that Heracles was regarded as a unifying symbol for the Romans and therefore, his cult was strong in Rome and beyond. Many Romans chose to have him engraved upon their rings seeking his blessing and protection. He was also appealing for young soldiers starting their military career.

I did not find any example of a gem bearing Heracles that would be personalised enough to claim it could be used as a family seal. Even if one narrows one’s research to one particular motif such as Heracles Musarum, which exists on both gems and coins alike,145 it quickly turns out that gems and coins were merely inspirational to each other. It was not the same idea (e.g. family promotion) shared but the same source of inspiration that unifies those two categories of archaeological artefacts (cf. chapter 13). Heracles Musarum on coins refers to the moneyer’s name making his issue easily recognisable and thus private, but the same scheme does not work in the case of gems with this motif.146 Inscriptions referring to the names of gems’ owners occurring on intaglios with Heracles’ image cannot be linked with the gentes of Fabia, Antonia, Potitia and Pinaria (cat. no. 6.108, Figure 34a-b). To sum up, because of the insufficient context, family propaganda and promotion of origo is not the primary reason for Heracles to appear on engraved gems in the Roman Republican period. There are more plausible explanations, but it cannot be entirely excluded that the hero’s image carried on a finger ring would testify to someone’s ancestry deriving from him.

Gens Caecilia claimed descent from Caeculus, son of Vulcan, who was the legendary founder of Praeneste. For this reason, representations of Vulcan and his features appearing on coins can be regarded as promoting that family.147 Interestingly, Vulcan working on armour for Achilles or a shield commissioned by Thetis is a popular motif on engraved gems (cat. nos 6.110-111, Figure 35). It can be debated if some of those intaglios were used as personal seals by members of the Caecilia family who wanted to promote themselves because of their legendary origo. There is no definite proof for that both in terms of iconographical elements and inscriptions. Vulcan, especially if paired with Thetis, indirectly refers to the Achilles story and this might be the reason for his popularity on Roman Republican gems.148 Nevertheless, an exceptional gem is an amethyst in Vienna with the bust of Vulcan to the left (cat. no. 6.112, Figure 36). The piece exhibits considerable similarities to the bust of Vulcan appearing on coins minted by M. Caecilius Metellus in 127 BC which iconography refers to the promotion of his family ancestry (Figure 37).149 Perhaps then, this intaglio served the same purpose as the coins.

A careful comparative analysis of coins and gems reveals further examples of the application of specific images that probably served to advertise certain families and their members. For instance, the Dioscuri on horseback rearing in opposite directions, heads facing one another with spears and stars above them, appear on the reverse of the denarius of C. Servilius M. filius struck in 136 BC (Figure 38).150 Crawford remarks that the image possibly served as a reference to the moneyer’s ancestor, supposedly Publius Servilius Geminus, consul of 252 and 248 BC.151 Indeed, this makes sense from the propaganda point of view as a transfer of authority from the illustrious ancestor to the moneyer. What is more, the image of the Dioscuri seems to refer to the family name too since the cognomen Geminus means ‘the twins’. It seems reasonable to think that the image from the coin applied to both aspects especially given the fact that Publius Servilius Geminus had a brother named Quintus Servilius,152 and perhaps it was used by other members of that family branch as a family symbol. This is supported by gems bearing similar iconography to the one from C. Servilius’ coin (cat. no. 6.113, Figure 39). It is likely that those gems like coins were used to manifest allegiance to the Gemini branch of the Servilia family and also transferred authority of the famous Publius Servilius Geminus onto their sitters.

Apart from mythological and divine figures, legendary Roman kings and their posterity were often taken as ancestors to the noble families in Rome. For instance, gens Marcia, one of the oldest and noblest family in Rome, claimed to descent from the fourth legendary king of Rome – Ancus Marcius.153 The Calpurnii claimed descent from Calpus, the son of Numa Pompilius, the second King of Rome while his brother Pompo served as an ancestor to gens Pomponia.154 Accordingly one finds the head of Numa on some of the coins of minted by Calpurnii and him also watching over a goat-sacrifice on the denarii struck by Pomponii.155 Another noble patrician family that originated from a son of Numa Pompilius was the gens Pinaria. Although, alternative tradition we have already mentioned was that they were descendants of Heracles,156 some of the Pinarii claimed to descent from Pinus, son of Numa too.157 Finally as already mentioned, gens Aemilia in the 2nd century BC established a tradition that said they originated from Mamercus one more son of Numa, although, another legend suggests that Aemilii originated from Aemylos, brother of Ascanius.158 The commonly used image of Numa Pompilius by the members of all these families on their coins as well as other images referring to their legendary ancestry derived from the first kings of Rome encourages us to search for similar representations in glyptics and consequently to propose that such images might have been related to one family or another.

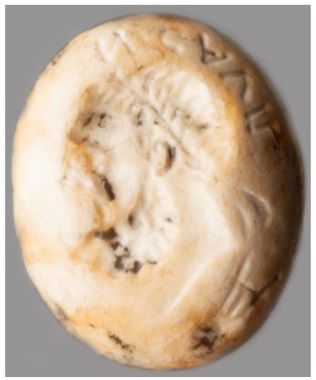

Vollenweider noticed a class of gems, usually sards that are circular or almost circular in shape (suitable for portraits) bearing a more or less homogenous group of male heads interpreted variably as Menelaos, Mars or Mercury.159 Indeed, these highly interesting portraits can be dated to the late 2nd and first half of the 1st century BC, when majority of Roman noble gentes started to promote themselves through their origo. Moreover, according to her, a closer look to this motif reveals that the class should be divided onto two groups: older and younger males.160 Once these portraits are compared to the coins issued by the above mentioned Roman gentes, it is tempting to inquire whether the first group of portraits could be identified as Numa Pompilius (cat. nos 6.114-138), while the second may show his sons (cat. nos 6.139-149). However attractive this hypothesis seems to be, it cannot be entirely accepted or rejected.

The group of elder male portraits can be split onto three further sub-types. The first one is an adult man with a long, pointy beard and crested helmet on the head (cat. nos 6.114-125, Figure 40). This is the most common representation that continues in relation to other heads which, however, do not have a helmet. These are archaistic representations of various deities: Mercury, Jupiter, Dionysus and so forth (cat. nos 6.126-128, Figure 41) which form the second sub-type. The third subtype is unusual since it also involves a portrait of an old, bearded man who has his hair rolled around the head or wears a diadem; sometimes he also wears a helmet, but a cap-like Italic version (cat. nos 6.129-138, Figures 42-43). Noteworthy is that the gods from the second sub-group are presented in a similar way on Roman Republican coins too, though, a bit later than on gems (Figures 44-45).161 This would suggest, the sub-type one (with a helmet) is Mars but he is also suggested to be simply a warrior.162 However, there seems to be a universal approach to the archaising images of deities and Roman legendary kings applied by coin-die makers in the late 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Similar heads to the ones known from gems also occur on several issues of Roman Republican coins minted in the 1st century BC by representatives of the families mentioned above (gentes Marcia, Calpurnia and Pomponia) and they are identified with Numa Pompilius and Ancus Marcius (Figures 46-49).163 It is evident that all three sub-types are based on one Italic-Roman portrait tradition as so rightly observed by Vollenweider (cf. discussion on this issue in chapter 6.3.2 below), however, not all of them should be recognised as depicting legendary kings of Rome.164 There are multiple explanations for their iconographies from images of deities to private portraits. Only two gems belonging to this class bear inscriptions, which do not help to identify these representations with Numa Pompilius or Ancus Marcius.165 Because of these inscriptions, Zwierlein-Diehl says that most of the gems in question represent private portraits.166 Nevertheless, comparative analysis with coin devices gives some hope of linking at least heads from the first and third sub-groups distinguished here with legendary Roman kings (Numa Pompilius or Ancus Marcius to be precise).167 Therefore, it might be hypothesised that some of those gems were indeed used by the members of various Roman families who claimed descent from legendary Roman kings.

As regards to the group of young male heads, they have been selected and presented here because they are cut in a similar tradition to the ones presenting older male figures discussed above (cat. nos 6.139-149, Figure 50) and examined to see if they are related somehow to the family propaganda of gentes descending from legendary Roman kings.168 It turns out that there is no supportive data available from coins or any other branch of Roman Republican art and craft to claim that these should be identified with sons of Numa Pompilius or Ancus Marcius.169 This homogenous group is cut according to the slowly-evolving tradition of the Italic-Roman portrait, which flourished at the turn of the 2nd and 1st centuries BC (cf. chapter 6.3.2 below). Some reminiscence of it is even noticeable in the early portraits of Octavian occurring on both, gems and coins (cf. chapter 9.3.1.4).

Concerning other families, as mentioned, gens Marcia derived its origo from Ancus Marcius whom some moneyers of this family put on their coins alongside Numa Pompilius.170 It is debated if those heads were family symbols used in glyptics as well, but one expects a prominent Roman gens to advertise its legendary ancestry in more than just one way. On a brown glass gem from Geneva Vollenweider spotted a Corinthian capital surmounted with a horologium – a solar device (cat. no. 6.152, Figure 51a-b). She links this peculiar motif with Q. Marcius Philippus, who constructed the Horologium in Rome in 164 BC.171 There are several other intaglios made of glass with the same device engraved upon (cat. nos 6.150-151 and 153-155). Among them the most intriguing one is the gem from Vienna combining a male head with the capital and the solar device (cat. no. 6.154, Figure 52). Zwierlein-Diehl admits it is difficult to find a parallel among architectural elements,172 so one wonders if the head refers to Q. Marcius Philippus which would suggest the motif to be related to the promotion of ancestry by the members of the Marcia family. Inscriptions found on some of these gems do not confirm such a supposition (cat. no. 6.155)173 but as evidenced, the view cannot be straightforwardly rejected.