Introduction

For most Americans today, the term propaganda brings to mind lies, brainwashing, and tyranny. Yet, like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, the United States saw a great increase in the use of political messaging in the early twentieth century. As this collection demonstrates, both Germany and the United States employed propaganda to influence American public opinion about Nazism, World War II, and the Holocaust.

The documents, illustrations, and recordings assembled here are examples of propaganda distributed by both the United States and Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. Taken together, they show how wars are not only fought with weapons, but also information and messaging. Armed with propaganda, both governments sought to influence American citizens’ opinions and secure public support in a time of conflict.

Although the concept of propaganda1 dates back to ancient times, it first gained widespread use as a tool for mass persuasion during World War I (WWI), when all the warring powers used it to motivate their populations and weaken their enemies. Like the tank, airplane, and battleship, propaganda became an essential and powerful weapon in modern warfare. Its supporters argued that it could shorten wars and ultimately save human lives by convincing the enemy to surrender.

President Woodrow Wilson established the first US propaganda agency in 1917,2 a move that received strong congressional and public criticism after the war. Concern arose over the fact that wartime propaganda had worsened widespread suspicion of and discrimination against individuals and groups not deemed to be “100 percent Americans.” Later revelations about the fabricated nature of many “atrocity stories” during the war made Americans more skeptical about propaganda.

A vibrant public debate in the United States concerning the effects of propaganda emerged shortly after WWI. In the 1920s and the 1930s, scholars in America and Europe published the first scientific accounts of propaganda and its functions.3 Some commentators feared that now Americans were living in an “age of lies” and that this form of messaging threatened democratic values and the freedom of the press by distorting and falsifying the news.4

During the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, Congress, and many other Americans remained fearful of propaganda in the years preceding the Second World War. Concern over foreign influence in American politics emerged with renewed strength. Beginning in 1934, Congress began investigating Nazi Germany’s propaganda efforts in the United States, which led to the creation of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1938. That same year, Congress passed the Foreign Agents Registration Act, which required persons “employed by agencies to disseminate propaganda in the United States” to register with the State Department.

Soon after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, senior Nazi official Joseph Goebbels began working to create a positive image of the new Germany in the United States. Goebbels’s Ministry of Propaganda and Public Englightenment identified propaganda campaigns as an effective means to counter negative press reports about the regime’s violence against political opponents and Jews. By the end of the 1930s, as Nazi Germany drove Europe into war, a new goal was added: encourage isolationism in America and keep the United States out of the conflict. A Nazi pamphlet included in this collection, recovered by an American college student, attempts to paint a favorable image of the Reich while making an appeal to American antisemitism.

Throughout the 1930s, Americans grew fearful of Nazi, Soviet, Italian, and Japanese propaganda in the United States.5 Yet they also believed that Great Britain and Jewish leaders and organizations were using propaganda to draw America into the Second World War. Isolationists like the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh made headlines by accusing American Jews and FDR of being pro-war agitators. That year Congress launched an investigation into the film and radio industry to determine if Jewish moguls in Hollywood were promoting pro-war propaganda as entertainment to direct public opinion and foreign policy.

Educators, too, worried that Americans could fall prey to propaganda. As a result, schools began to teach students how to identify propaganda. The newly created Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) continued these activities. Using examples from current politics, the IPA provided teachers and students with materials to make them more critical consumers of information. A leaflet included in this collection, “Hitler Wants You to Believe…,” worked to the same effect: readers were warned to be skeptical of rumors spread by the Nazis and their allies.

Despite his reservations about the dangers of propaganda, President Roosevelt created the Office of War Information (OWI) in 1942. The agency coordinated the government’s messaging about the war effort through film, radio, newspapers, posters, and pamphlets. OWI officials wanted to avoid the mistakes of the past war by toning down “hate propaganda.” They stated that the OWI “must give the people a truthful, clear, and uncompromising picture of the enemy.” This task, they maintained, was impossible without providing a “frank account of what the enemy does.” One OWI poster featured in this collection, released following the 1942 murders of hundreds of innocent Czech civilians, reflects horror and dismay at the Nazis’ capacity for brutality. While the purpose behind such accounts was to supply the public with “all the facts about the war and the enemy,” it could also stir outrage and action.

Beyond casting light on the dangers posed by the Axis powers, American propaganda focused on encouraging participation in the war—whether through employment in the armaments industry, conservation of valuable resources, or service in the armed forces. Recruitment posters like the one featured here touched upon patriotic themes to generate enthusiasm for joining the military.

As information about the Holocaust and other Nazi mass atrocities came to light, some concerned Americans sought to publicize these crimes in order to generate public and governmental action. America’s official propaganda agencies, too, remained wary of promoting stories about Nazi crimes out of fear that they would be dismissed as “atrocity stories” like those that circulated after the First World War.

The shock that many American soldiers experienced when they encountered the concentration camps in 1945 quickly led to concerted military and governmental action to publicize Nazi crimes. A short film created to expose the horrors of Nazi camps—and to ensure that they were not dismissed as mere propaganda—appears in this collection. General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s appeals to Washington in April 1945, imploring journalists and members of Congress to visit the Nazi death camps, were an attempt to ensure that such horrific atrocities would never be again attributed to “propaganda.”

Propaganda—whether in the form of artwork, radio and television broadcasts, or print media—provided both Nazi Germany and the United States an important tool for communicating and promoting official policies and actions during the Second World War. No major power recognized this more clearly than the Third Reich, but the United States also used propaganda to advance its war aims. Indeed, in the battle for Americans’ hearts and minds, it proved perhaps the most powerful weapon.

German Leaflet Alleging Allied Atrocities

of atrocities during wartime can dramatically reshape public opinion and behavior. Beginning in World War I, Allied officials created propaganda claiming that the German army had committed horrific crimes against civilians. Their goal was to mobilize the home front to support US involvement in the war. Even Adolf Hitler, who had served on the front lines in the WWI, admired the British and Americans for their skillful portrayals of the enemy.6

Following WWI, revelations about the fabricated nature of many of these Allied atrocity stories made some Americans skeptical of propaganda, particularly reports of mass crimes against civilians. Anger and resentment about having being manipulated to intervene in WWI helped to fuel anti-war sentiment.

During World War II, Allied officials expressed reservations about spreading “atrocity stories.” Their Nazi counterparts, however, made full use of them. In the lead-up to the occupation of the Sudetenland in fall 1938 and the invasion of Poland the following year, the German Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda published stories of Czech and Polish violence against ethnic German civilians, arguing that they needed to be avenged. Following Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, Nazi propagandists used real Soviet atrocities against local populations to encourage pogroms against Jews and to justify their mass murder as reprisals for Soviet crimes.

In Germany and elsewhere in Axis-controlled Europe, the public display of such gruesome brutalities, whether in posters, in cinema newsreels, and other press, had the effect the Nazis had desired. Audiences in movie theaters in the summer of 1941 screamed or turned away in shock, sometimes demanding harsher measures against Jews, who were falsely presented as the perpetrators of the violence in these “atrocity stories.” Photographs and film footage gave this propaganda an air of authenticity.

Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels also understood that he could counter reports about cruel treatement of the Jews for audiences abroad by claiming these were “atrocity stories,” invented by “international Jewry” and political opponents. He also used reports of real crimes by the Soviets, such as the Katyn Forest Massacre7 to try to divide the Allies.

On the battlefield, the German armed forces created and disseminated extremely graphic leaflets exposing recent Soviet crimes and denouncing the Allied bombing of Dresden as an “atrocity.”8 Like the leaflet displayed here, dropped on Allied soldiers in Italy in 1945, these materials played upon emotions and aimed to raise doubts in the minds of soldiers about the justness of their cause.

German Leaflet for African American Soldiers

During World War II, Axis and Allied forces dropped millions of leaflets behind enemy lines. In contrast to political propaganda campaigns, this battlefield propaganda did not seek to convert the targeted audience over to a particular cause, but to weaken military morale and convince soldiers to surrender.

Leaflets and broadcasts at the front frequently played on the soldiers’ homesickness, the will to survive, jealousy, fears, and even prejudices. Because of the multi-national, multi-racial, and multi-ethnic composition of the various armies engaged in war on both sides, propagandists often targeted particular groups try to cause dissension within the ranks.

German propagandists were well aware of widespread racism in the United States and in the US Army, as evidenced in this Nazi leaflet aimed at African American soldiers.9 Their goal was not to convert blacks to Nazism, but to convince them to desert and surrender. The Nazis considered blacks to be racially inferior and a threat to “Aryan society,” but they intentionally avoided such notions in leaflets like this one.

For their part, black infantrymen did not need to look far for reminders of inequality in American life during the 1940s. The army was segregated and race riots erupted in Detroit and other American cities in 1943.10 Moreover, the US Congress would not pass anti-lynching legislation during 1930s or 1940s, despite some public pressure to do so.11 Many black Americans hoped that the defeat of the Axis Powers would be a double victory over the enemy abroad and for equal rights at home.12

This leaflet illustrates some of the ways in which Nazi propagandists try to reach African American soldiers, deliberately concealing Nazi racism with claims that “colored people living in Germany can go to any church they like. They have never been a problem to the Germans.” African-American soldiers, the flyer declared, need not fear Germans for there never have been lynchings of “colored men” in Germany, where they “have always been treated decently.”13

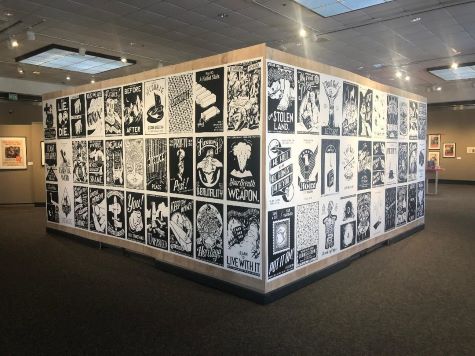

“‘Propaganda Kit’ Made in Germany”

Beginning in 1933, Nazi Germany attempted to influence American public opinion using a variety of strategies. They hired US public relations firms, broadcast via radio from Berlin, created academic exchange programs for American college students, and even opened a German Library of Information in New York. The Nazi Regime’s goals were several: to create a positive image of Hitler’s Germany, to counter accusations of Nazi brutality against Jews and political opponents, and to encourage social tensions in the United States. In doing so, Nazi authorities hoped to keep the United States out of the war in Europe.

In spite of these many efforts, Nazi Germany’s rearmament and ruthless treatment of internal “enemies” did much to counteract its propaganda campaigns. Just as importantly, Nazi activities in America were uncovered by journalists, congressional committees, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Jewish organizations, veterans groups, and even ordinary citizens. These revelations gained almost immediate media attention and brought public attention to Nazi propaganda efforts.

An organization called the National Americanism Committee of the Disabled American Veterans took several measures to expose Nazism in America. The organization was run by Roy P. Monahan, a World War I veteran and New York attorney. In September of 1938, Monahan testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which was investigating Nazi propaganda in the United States. He informed the congressional representatives that the German-American Bund wanted to instill children with “poisonous un-American doctrines.”14 He charged that the Bund’s recreation center on Camp Siegfried, on Long Island, New York, was indoctrinating children with Nazi ideas.

Two months later, Monahan addressed a “Thank God for America” rally held by the Jewish War Veterans of the United States. He announced that his organization, along with the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, were launching a campaign to change US immigration and postal laws. One measure would ban the mailing of “misleading matter tending to incite religious intolerance or race prejudice.” Another law would attempt to prevent naturalization for non-citizen immigrants who had participated in organizations deemed anti-American.

Monahan and his National Americanism Committee of the Disabled American Veterans published a brochure, “‘Propaganda Kit’ Made in Germany,” selections from which are included here. The publication drew links between the “hate-inciting literature” published by the German “news agency” Welt-Dienst [World Service] to allegedly independent “patriotic organizations” in the United States. The pamphlet reminded Americans that the country was vulnerable to “sabotage from within,” particularly from American fascists. The solution, it concluded, was simple: “We cannot reach the source of this filth, as we did in 1917, but the poison pumps that are busy in our own land must be plugged.”

Lidice: “This Is Nazi Brutality”

Nazi atrocities captured more public attention or stirred more emotions in the United States than the brutal destruction of the Czech village of Lidice on June 10, 1942. In retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich—the German official in charge of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and one of the leading architects of the mass murder of Europe’s Jews—Hitler ordered all 173 male inhabitants of Lidice executed, the women deported to concentration camps, and the children deemed suitable for Germanization sent to SS families for upbringing. SS forces obliterated the village.

Though it was just one of many bloody reprisal actions and war crimes committed by Nazi Germany, the massacre in Lidice received worldwide media coverage, in part because the German leadership made no secret of the village’s destruction. Within days, Americans, leaders and the general populace, responded to this Nazi atrocity.

On June 12, 1942, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull condemned the massacre as a the work of a “savage tribe” that had “shocked and outraged humanity.”15 But it was not only politicians who reacted to the crime committed at Lidice. A Gallup poll conducted at the end of that month asked Americans what should be done with Hitler and the other Nazi leaders after the war.16 The majority of respondents called for the shooting, hanging, or imprisonment of these Nazi officials. A month later, on August 21, Roosevelt warned the Axis powers that the United Nations would hold them accountable for their “barbaric crimes,” including the shooting of hostages and reprisals against civilian populations.17

Lidice quickly became a fixture in American culture: several Hollywood films were made about the massacre; Edna St. Vincent Millay composed a book-length poem, The Murder of Lidice, which was excerpted and broadcast on radio around the world; poet Carl Sandburg too paid tribute to the murdered village in a piece for The Washington Post.18 A small village on the outskirts of Joliet, Illinois, even renamed itself Lidice in tribute to the Czech town’s memory.

An American Jewish artist named Ben Shahn took up his paintbrush to memorialize Lidice in this featured poster for the Office of War Information, America’s official propaganda agency. For Shahn, the turbulent events of the 1930s and World War II dramatically shaped both his art and his politics. The war, and the incomprehensible violence it unleashed, forced him to consider the great potential for art, beyond “personal pleasure.”19

To create this poster, Shahn drew on US newspaper reports and other media for source materials. Rather than graphically depict the massacre or the perpetrators, he focused on the heroism of the victim who bravely awaits execution. The original German communiqué on Lidice, added as the image’s caption, conveys the naked ruthlessness of Nazi occupation policy.

“Americans Will Always Fight for Liberty”

Beginning during the World War I (WWI), large color posters became essential weapons in the propaganda arsenal of all the warring powers. Once used to market and advertise products, posters began to serve in support of the war effort. The public was encouraged to donate funds for war bonds or join the armed forces, conserve resources, and hate the enemy. Posters also helped to express and popularize each nation’s war aims.

During World War II, propaganda agencies recruited artists, both from the fine arts and from the more popular illustrated journals, to design posters. As one American propaganda official, George Creel, explained: “It was not only that America needed posters, but it needed the best posters ever drawn.”20 To reach the millions of immigrants in the United States, Creel’s agency—the Committee on Public Information (CPI)—produced in many different languages, including German, Norwegian, Ukrainian, and Russian.

Creel and the CPI had learned to appreciate the powerful appeal of the poster. Describing his work during WWI, he remarked: “What we wanted—what we had to have—was posters that represented the best work of the best artists—posters into which the masters of the pen and brush had poured heart and soul as well as genius.”21

More than two decades after WWI, American propaganda officials contacted the country’s artists and advertisers to shape messaging for the fight against the Axis. Francis E. Brennan, the art director at Fortune magazine, was selected to lead the Office of War Information’s Division of Graphics. Brennan sent an urgent plea to American artists:

….the essence of art is freedom. Without it the world of art could not exist. We know that the enemy is trying to destroy freedom—that he has long since chained together his men of talent. We know the total pattern of his wretchedness—we saw it first when he destroyed the works and lives of those whose art was a threat to his evil purposes….We saw, in short, an unprincipled plan to degenerate and possess men’s minds.22

Although Brennan made no mention of Adolf Hitler or Nazi Germany, many understood his statements as referring to Nazi book burnings and the Party’s attacks on modern art.

Graphic artists like Bernard Perlin23 answered Brennan’s call. To lend their works greater power and spark patriotic feeling, Perlin and others often rooted them in dramatic scenes from American history.5 In the poster presented here, Perlin places Americans fighting the Axis powers in line with the struggle of soldiers in the Revolutionary War.6 How might such a comparison have motivated Americans to fight?

“Careless talk. . .got there first”

During World War II, the US government drew on the expertise of the advertising industry to help craft messages for the American public. In early 1942, representatives of the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF), Washington’s newly-created propaganda agency, sought the advice of a Madison Avenue advertising agency to create effective posters for the war effort. The advertising agency commissioned a report that it shared with the OFF. Among the crucial questions the ad men addressed was whether the posters had emotional appeal for the audience. Underscoring what the Germans and others had discovered earlier, the report concluded:

THE MOST EFFECTIVE war posters appeal to the emotions. No matter how beautiful the art work, how striking the colors, how clever the idea, unless a war poster appeals to a basic human emotion in both picture and text, it is not likely to make a deep impression.24

To effectively motivate viewers, the poster needed to rely on realism, not an abstract or symbolic style, since art done in the latter manner was often misunderstood or not understood at all.

The firm Young & Rubicam carried out user testing by surveying audiences in Toronto and gauging their responses to the posters.25 A majority of the 11 most effective posters appealed to emotions, while the least effective category were done in either in an abstract style or were cartoons. Viewers, they discovered, did not like humorous war posters. The key finding of the report was:

War posters that make a purely emotional appeal are by far the best. In this study, such war posters definitely attracted the most attention and made the most favorable impression among men and women alike.26

Appealing to the public’s emotions proved to be critical in changing American behavior. One of the most important tasks in any war is to prevent the enemy from acquiring vital information that could harm the nation’s war effort. Every power in World War II produced posters aimed at getting the populace to not to spread news of troop movements, the dates of a particular attack, or other sensitive data.

The Office of War Information and other government agencies produced and distributed a variety of dramatic images on these themes, accompanied by punchy slogans like “Loose lips sink ships” and “Careless talk costs lives.” These popular posters made audiences accountable for their actions by emphasizing that unguarded behavior could lead to the deaths of Americans. Implicit in such propaganda was the notion that among the population were traitors, spies, and foreign agents. This poster, “Careless talk. . .got there first,”invoked this fear with a grisly portrayal of a dying American serviceman.27 What emotional responses might such a poster evoke?

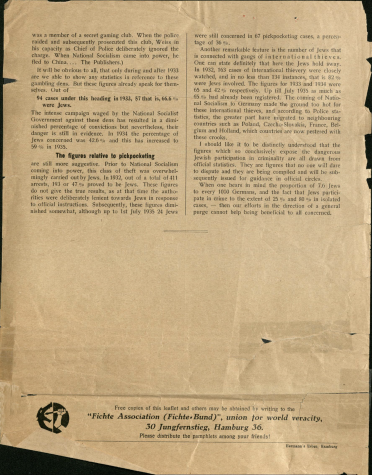

German Leaflet: “Jewry and Penal Punishment”

Soon after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, the Nazi regime began working to create a positive image of the new Germany in the United States. Its aim was to counter negative press reports about the Reich’s violence against political opponents and Jews.28 By the end of the 1930s, as Nazi Germany drove Europe into war, a new goal was added: keep the United States out of the conflict. German officials were well aware of Imperial Germany’s failure to sway American public opinion in World War I and sought to avoid that outcome.

Josef Goebbels’s Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment hired prominent American public relations firms to promote favorable views of Hitler’s government and targeted various sectors of the American population—German-Americans, tourists, academics, politicians, right-wing organizations—with specific messaging. In 1933, the Ministry began radio transmissions to the Americas. More important, the Ministry distributed large amounts of printed material, supplied in the United States by the German Library of Information and other outlets. The Nazi regime devoted considerable funding and manpower to influencing Americans attitudes. Customs and postal officials calculated that by 1940, the German government was transporting tons of propaganda materials by ship each month, which then would be distributed through the US mail.29

The Fichte Association [Fichte-Bund] was one of the prolific creators and distributors of Nazi propaganda. Controlled by Goebbels’s ministry, it spread millions of leaflets across the globe in more than a dozen languages. These publications were provided free of charge and were advertised in newspapers or magazines sympathetic to the Nazi or fascist cause.30

Like much of Nazi propaganda for Western nations, the Fichte Association’s leaflets portrayed Hitler as an advocate of world peace, warned of the dangers of Communism, denounced the Versailles Treaty, and declared the benefits of Nazi racial legislation, including sterilization of individuals deemed biologically unfit. Its publications also tried to counter Western critics’ claims about Nazi Germany’s treatment of the Jews and justify the regime’s anti-Jewish measures, often by playing on antisemitic sentiment in the United States. As a deeply negative portrayal of Jews—supported with falsified statistics—the flyer featured here describes Jewishness itself as criminal, a common Nazi characterization.

Although the Fichte Association’s materials frequently circulated among far-right political groups in the United States, they also appeared on college and university campuses, where Nazi propagandists hoped to achieve some success. By presenting a positive image of Hitler’s Reich and sowing doubt over the accuracy of newspaper reporting about Germany, they attempted to reshape American students’ opinions and behaviors.31 Ettore Peretti, an American graduate student attending university in Germany, received the featured leaflet sometime in 1935 or 1936.

Robert Henry Best: “Best’s Berlin Broadcast”

the early 1920s, radio broadcasting offered governments a new means to shape public opinion and behavior. Radio Moscow began transmitting its programming internationally in 1929. By 1939, German broadcasts were reaching the European continent, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Western Hemisphere. During the World War II, Nazi broadcasts from Berlin and other parts of German-occupied Europe expanded with transmissions in some two dozen languages.

Government officials quickly saw that audiences were more likely to respond positively to broadcasts from native speakers who had knowledge of and roots in that country. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels tailored messages to foreign listeners in an effort to generate favorable impressions of Nazi Germany. These broadcasts did not primarily aim to convert listeners into Nazis but to challenge the messages presented by Allied governments.

A number of Americans, men as well as women, broadcast from Nazi Germany. Notorious among them was William Joyce, a New York-born British fascist who took on the moniker of “Lord Haw-Haw.”32 Most of these broadcasters had been relatively unknown in the United States before they took to the German airwaves. A few were experienced journalists who had been serving as foreign correspondents for American media outlets. One of these was Robert Henry Best, a South Carolinian who began reporting from Europe in the 1920s.

In his transmissions from Berlin, Best criticized the Roosevelt administration, Communism, and the Jews. He also denied that he was working for Nazi Germany. In a May 25, 1943 broadcast, he attacked his critics:

I have never shouted Nazi propaganda in any microphone anywhere. What I have broadcast and what I shall continue to broadcast is every word native-born, dyed in the wool propaganda of an America, by an American, and for America. I am an American born and an American bred and when I die I shall be an American dead. Awake, America, Awake! Arise! Down with the Judocrats! Oust the Rabbis. BBB Best’s Berlin Broadcast. BBB Triple B. Carry On.33

In 1943, Best announced his candidacy for the American presidency in the 1944 elections. What motivated him is unclear, but certainly his hatred of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and “international Jewry” were key factors. Responding to some of his critics in the United States, Best identified a central pillar of his platform: “I…demand the head of one of America’s Jewish bankers for every American man or boy who is killed or even wounded in the course of the present war.”34

Best’s broadcasts, along with those of other American radio commentators, did not go unnoticed in the United States. In 1943, the US Attorney General charged Best with giving assistance to the enemy. The Federal Bureau of Investigation worked with the Federal Communications Commission to collect evidence of his treason. Transcripts and recordings were made of his broadcasts—one of which is presented here—providing evidence when he was finally arrested and placed on trial. In March 1948, a court found him guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment and a $10,000 fine. He died in December 1952, while serving his sentence.

“Hitler Wants Us to Believe…”

plays an important role in strengthening morale at home during wartime. It also aims to weaken the morale of the enemy. Governments create and distribute messages that stress internal unity and strength on the home front. Propaganda may also seek to increase class, racial, or political friction within an enemy society. One method of encouraging such discord, as illustrated in the featured poster, is spreading rumors through a kind of word-of-mouth propaganda, sometimes called a “whisper campaign.”

Although using rumors for political purposes stretches back centuries, a more systematic approach to this kind of messaging began only in World War II. One American scholar commented in 1944 that “the rumor must be likened to a torpedo; for once launched, it travels of its own power.”35 Propaganda through rumor has another advantage: it is often not immediately recognizable as propaganda. Once a rumor begins to spread widely, there is little which can confirm its source.

The rapid defeat of France in a matter of weeks in the spring of 1940—shocking many Americans—evidenced the success of this Nazi strategy. A booklet, produced by the US propaganda organ known as the “Office of Facts and Figures,” charged that “professional weepers, clothed in deep mourning and wailing loudly” had spread false stories of enormous French casualties at the start of the campaign. “Palm readers and crystal gazers in the pay of Hitler gloomily predicted to their clients” France’s downfall.36 Such rumors spread throughout all the invaded nations, weakening resistance and speeding defeat.

Other rumors divided populations by playing on racial divisions, class tensions, and religious prejudices. These “whisper campaigns” grew common, and became a source of great concern to US propaganda agencies. In September 1942, the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety, documented more than 1,000 rumors then in circulation. Hundreds of them contained anti-government, anti-British, or anti-Jewish themes.37

Some scholars challenged the government’s view that the Nazis had planted these seeds of conflict in American society. In ascholarly study of propaganda commissioned by the US government, one member of the Institute of Propaganda Analysis commented:

In any nation there is already, by the nature of things, disunity. The smart propagandist plays upon this disunity, seeks to increase it. Thus, wartime efforts by the Axis to increase disunity among minority groups in the United States and the United Nations conform to a propaganda pattern which brought the Axis into a position of great power before World War II began. For its success, this pattern has depended upon group differences and groups antagonisms which antedate the Axis.38

Drawing on scholarly studies of propaganda, the poster featured here attempts to combat rumors spread by Nazi propaganda. The artist—Daniel Fitzpatrick, a cartoonist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch—listed a number of Nazi-sponsored falsehoods designed to incite race hatred: “Jews cause everybody’s troubles, everywhere”; “This is a ‘white man’s war'”; the threat of a “Yellow Peril.” Were these prejudices inspired only by Nazi propaganda? To what extent did they reflect American attitudes preceding the war?

Norman Krasna, “Lest We Forget”

Footage shot by US Army Signal Corps members forms some of the most graphic and searing imagery of the postwar period. Emaciated prisoners, piles of dead bodies, and crumbling concentration camp infrastructure constitute only a few of the iconic images filmed and then shown in newsreels throughout the United States. These photographs and film footage all fell into a general category of atrocity footage that sought to record or reconstruct some of the more graphic mechanisms of the mass killing process. Foregrounded by US officials who sought to counter the popular impression that atrocities during wartime were exaggerated or falsified, they also became widely circulated in the American press.39

The shock experienced by the men behind the camera was, in many ways, palpable and fresh. There was, for many soldiers, a growing sense that this was no ordinary prisoners and victims. Indeed, for American liberating forces, this was often the first time they had heard of the kinds of war crimes that, in 1945, soon to be commonly described as “genocide.”

In a letter dated May 15, 1945, Jewish-American soldier Irving P. Eisner wrote to his father in Cleveland:

I don’t know how to begin this letter, but I’ll try this. Today I visited ‘Buchenwald’ (I hope that got by the censor). I learned a lot today about life and death at a concentration camp, for the past three, four, five, and six years for political prisoners. You know who those are—anti-Nazis by religion and nationality. Six years ago while I was in high school, millions of people were suffering and dying beyond approach of human thought.40

Eisner’s letter goes on to describe his impression of the Buchenwald concentration camp. At the close of the letter, he implores his father to try to locate a survivor’s uncle in Cleveland. Tellingly, he also never identifies this survivor—nor any other “political prisoner” or “co-religionist” as explicitly Jewish. The overall tone of Eisner’s letter, however, is fairly typical of this genre of correspondence; it represents an average soldier’s response to the horrors of the concentration camp system.

Postwar liberation footage had several different audiences in mind, and those imagined audiences affected the ways in which these films were constructed. Although raw footage was often filmed for the purpose of documentation, it was sometimes edited for use in newsreels pitched for the general public. At the same time, these films were constructed as films, and therefore followed aesthetic concepts and conventions.41 Many images from these newsreels became iconic and frequently reproduced what came to be tropes of the Holocaust and genocide. For example, footage of bodies bulldozed by Allied troops after the war (often in an effort to dispose of bodies after rampant typhus epidemics) became shorthand—or even mistaken for—death camp atrocities. Mass burials, too, were often initiated by the Allies as they attempted to clear out what had been a site of mass murder.

The following footage, edited into a short newsreel entitled “Lest We Forget,” was recorded by Captain Ellis Carter and Lieutenant William Graf of the US Air Force Motion Picture Unit. Norman Krasna, a Jewish American screenwriter and member of this same unit, obtained the footage and edited it with his own narration. A screenwriter with significant American film titles to his name, he was most famous for his script, Princess O’Rourke, which won an academy award. In 1954, he went on to write the screenplay for White Christmas, starring Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney.

Krasna’s film depicts Buchenwald and Dachau, with footage taken in the immediate aftermath of liberation. The footage (some of it in color) that Krasna uses here is graphic, and relatively standard for this genre. Indeed, Krasna focuses on some particularly grisly images, including those of medical experiments. He also perpetuates common narratives that we now know to be discredited, such as certain aspects of medical experimentation, or the supposed lamps made with human skin. Krasna’s narration also, however, makes several specific mentions of atrocities against Jews—a somewhat unusual move for the time.

The film ends with an indictment of the American public, watching such images in comfort and safety:

Well, that’s what it was like. Except for the smell, you’re now a big expert on Buchenwald. If anyone tells you atrocity stories are exaggerated, think of these people. Lawyers, doctors, editors, musicians, judges—it’s hard to believe these people were rich and dignified, when their ribs are sticking out. And who can tell who’s a Jew and who’s a Christian in this pile? Perhaps the man across your dinner table, who tells you these things are exaggerated, knows the difference.

WARNING: The footage contains graphic images of dead bodies and nudity.

Roosevelt’s Address on the “Fifth Column”

Nazi Germany’s invasion of northern and western Europe in the spring of 1940 deeply shocked Americans. Many credited the fall of France in less than six weeks not to military weakness, but to the weakness and panic created by a Nazi “Fifth Column.”42 The rapid German victory increased fears of subversion and foreign propaganda at home in the United States. It was widely believed that the Nazi “Fifth Column” served as the advance force of the German military, paving the way for invasion.

Even before the French army surrendered, President Franklin Roosevelt took to the airwaves on May 26, 1940, to assure the American people of the country’s military preparedness and to criticize those who closed their eyes to what was happening in Europe. But just as importantly, he stoked fear, warning of a growing threat to American security: “the Trojan Horse. The Fifth Column that betrays a nation unprepared for treachery.”43

According to Roosevelt’s address, a portion of which is featured here, the methods of these “spies and saboteurs” was “to create confusion of counsel, public indecision, political paralysis and, eventually, a state of panic…. The unity of the State can be sapped so that its strength is destroyed.”

Roosevelt’s statements about a Nazi “Fifth Column” in the United States, which were echoed by other politicians and media, generated widespread public concern. At a press conference in May, several reporters questioned the president about the growing “hysteria” concerning the “Fifth Column” in America. One journalist even asked whether he and other government officials bore some responsibility for the panic, and questioned the existence of such anti-state forces. As proof, Roosevelt reported that members of a “Fifth Column” had attempted to destroy tools in over forty US factories.44

The widespread fear of a Nazi “Fifth Column” had both predictable and unforeseen consequences. Suspicion fell upon those deemed “foreign” or unpatriotic, such as undocumented residents in the United States; Jehovah’s Witnesses; American citizens of German, Italian, and Japanese descent; and refugees trying to get into the country.45 US officials worried that the situation might boil over, noting that it could be necessary for the government to pressure local and state officials to maintain order.46

Dr. Fritz Linnenbuerger: “Trip to Germany”

Throughout the 1930s, the Nazi regime attempted to reach German-American audiences to spread positive images of the “New Germany” in the United States. Organizations such as the Friends of New Germany and the German American Bund provided an ideal medium through which to spread this brand of propaganda. The German Teachers’ Association,47 which sponsored a trip to the Third Reich for 70 teachers in the summer of 1939, also enabled the Nazi government to project an image of a revitalized nation working toward a strong and peaceful society. Many participants returned home carrying positive impressions of “Germany as it is today.” The potential of such attendees to be a subversive force on American soil attracted the attention of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which suspected the trips were aimed at German-American newspaper editors.

Returning from the German Teachers’ Union trip in September 1939, Dr. Fritz Linnenbuerger, a resident of Ashley, North Dakota, expressed his support for the Nazi government in a report. He submitted the text for an article in a Russian-German newspaper, the Dakota Freie Presse (Dakota Free Press).48

In his report, Linnenbuerger describes his tour across the “new Germany” which included a visit to Buchenwald concentration camp. He concluded that the situation there “[was] altogether different from that reported,” with conditions not unlike “any other penal institution.” Those who complained of the “terrible” conditions of the camp were most likely “criminals.” Other reported highlights of the visit include a meeting in Munich with Rudolf Hess, Deputy to Adolf Hitler, and an encounter with Hitler himself on September 1, 1939,49 in Berlin. In his brief address to the Linnenbuerger’s group, Hess urged the audience, upon their return to America, to “tell your loved ones all about it.”

Louise Kleuser to J. L. McEhlany

The Nazi regime paid close attention to its public image both at home and abroad. In addition to formal diplomacy and propaganda, it relied on ordinary Germans who could communicate positive messages about Germany to foreign audiences.50 German church leaders became important tools in this project because they were seen as moral authorities and had connections with Christians in other countries. A number of German ministers and church officials went on speaking tours in the United States in the mid-1930s to counter the negative press about domestic Nazi policy and its restrictions on freedom of religion. In some cases they were supported by the German propaganda ministry.

In 1936, Hulda Jost, the director of the German Seventh-Day Adventist51 welfare organization, went on a speaking tour across the United States.52 In addition to the General Conference of the Seventh-Day Adventists in Washington, DC, the German government facililtated the logistics of Jost’s trip. Jost gave over 140 public lectures during her four-month trip between March and June 1936. Some of her audiences were church congregations, but she also spoke to community groups, college students, and women’s groups. Local American newspapers covered her lectures and German diplomats working in American cities attended some of the events.

The General Conference of the Seventh-Day Adventists arranged for a translator, Louise Kleuser, to accompany Jost on her tour. Kleuser, also an American Adventist, wrote the featured letter to J. L. McElhany, the president of the Adventists General Conference. Five weeks into the trip with Jost, Kleuser offers a more critical perspective on the lectures than seen in American newspapers. She warns church leaders that Jost’s lectures were often overtly political, rather than religious or educational.

“Desecration of Religion”

Created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in June of 1942, the Office of War Information (OWI) designed and spread propaganda both in the United States and abroad during World War II. The OWI produced posters, films, photographs, and exhibitions to promote civilian support of the American war effort, often portraying Nazism as a direct threat to the United States and to American values.53 Many of these materials framed Christianity as inherently American and used religious imagery to evoke American identity.

The featured photo depicts The Nature of the Enemy exhibition, an example of this approach and one of many OWI exhibitions staged on the plaza at Rockefeller Center in New York City during the war.54 Running from May 17 to July 4, 1943, it included a replica of a typical American Protestant church, pictured here. A tableau below reads “The Desecration of Religion,” accompanied by a caption: “The simple, colonial church that symbolized American religion has been burned and battered by the Nazis before they barred the door with the sign: ‘Closed by the Gauleiter of America.'”55 The tableau also featured quotations from Axis leaders on their supposed derision or rejection of Christianity, for example, “‘Adolf Hitler is the true Holy Ghost.’ Hanns Kerrl, German Minister for Church Affairs.”

A tableau beside the church is titled, “Militarization of Children.” Other tableaus included those titled “Abolition of Justice” and “Slave Labour.” Partially visible in this photograph is a large banner hung from a building, which reads, “The Enemy plans this for you.” The OWI cast “the enemy” here as all Axis nations, not just Nazi Germany.56 The caption suggested that the Axis powers posed a serious threat to American values and underscored that Protestant Christianity was a core feature of American culture. Nevertheless, the exhibit’s creators preferred the term religion in the title rather than Christianity or American Christianity.

“Nazi Exchange Students at the University of Missouri”

Throughout the 1930s, the Nazi Party used propaganda to shape public opinion in the United States.57 To support this effort, the regime sent more than 350 German exchange students to American universities in the years before World War II. Beginning in 1936, these young Nazis—who were carefully trained to spread pro-Nazi ideas and generate sympathy for Germany—were sent to influence students and faculty on US campuses.58

One of these students, Elisabeth Noelle (later Noelle-Neumann), arrived at the University of Missouri in Columbia in the fall of 1937. She was sponsored by the Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority, which sent an exchange student from its chapter in Columbia to study music and German in Munich.

Noelle’s outspoken support of Adolf Hitler drew attention on campus, including this in-depth news article by a Jewish journalism student named Esther Priwer. Printed first in a student newspaper59 and later in the national Jewish magazine The Menorah Journal, Priwer’s article attempts to explain ” firsthand how an ‘Aryan’ German regarded the Jews.” Priwer describes Noelle as “neither unfriendly nor friendly” to Jewish students, but she also notes that Noelle wrote pro-Nazi opinion articles and openly spread her Nazi views in the classroom and elsewhere on campus.60

Priwer describes only one personal encounter with Noelle, recalling that it was “hard to believe that Elizabeth was a deadly enemy of my people. She was such a charming person!” Priwer also observes that “Elizabeth is very attractive…that is undoubtedly one reason why Hitler sent her here.”

Noelle’s advocacy on behalf of the Third Reich met with mixed reactions at the University of Missouri. Anti-German sentiment on campus was higher even than at the height of World War I, and most professors “either resented her or laughed at her.” Priwer observes that Noelle’s highly publicized opposition to “the mixture of races,” was received “tolerantly” by her classmates. She notes, however, that Jewish students regarded Noelle with “pity” for being merely “the product of the Nazi regime.”

Priwer’s article prompted some of her classmates (whom Priwer describes as a “liberal group” of mostly non-Jewish students) to write to the American Jewish Council, asking the organization to expose the propaganda efforts of German exchange students. The resulting report (attached as an addendum to Priwer’s article) was circulated around the University of Missouri campus to warn students and faculty of a major campaign to influence their attitudes toward Nazi Germany.61

Upon her return to Germany in 1938, Noelle went on to work as a journalist in the Nazi press. Following the war, she became a well-known academic with expertise in public opinion research. Noelle’s presence on an American campus once again became a source of controversy in 1991, when a series of articles about her Nazi past appeared during her term as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago.62

Endnotes

- In this collection, propaganda is defined as biased information designed to shape public opinion and behavior. It can be spread by governments, political parties, or private organizations to advertise a particular cause, movement, candidate, or nation. It generally plays upon emotions, selectively omits information, and succeeds when its targeted audiences respond positively to its messages.

- For more information on the roots of American propaganda, see Alan Axelrod, Selling the Great War: The Making of American Propaganda (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- For an interesting discussion of this public debate, see Erika G. King, “Exposing the ‘Age of Lies’: The Propaganda Menace as Portrayed in American Magazines in the Aftermath of World War I,” Journal of American Culture, Vol. 23, Issue 2 (June 2000), 17-23.

- “Propaganda—Asset or Liability in Democracy?” America’s Town Meeting of the Air, Series Two, Number 22, April 15, 1937 (New York: American Book Company, 1937), 12-14; for additional information on Bernay’s views on propaganda, see also Edward L. Bernays, Propaganda (New York: Horace Liveright, 1928); “Manipulating Public Opinion: The Why and The How,” The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 33, No. 6 (May 1928), 958-971; “The Marketing of National Policies: A Study of War Propaganda,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Jan., 1942), 236-244; “The Engineering of Consent,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 250, Communication and Social Action (Mar. 1947), 113-120.

- Officials also warned of a so-called “Fifth Column” that was poised to sabotage industry and terrorize the population. The term “Fifth Column” dates back to the Spanish Civil War, and is attributed to Nationalist general, Emilio Mola, who reportedly announced that he was sending four military columns to advance on Madrid and had one column of sympathizers and agents operating inside the city to aid the revolt. It quickly entered into the popular vocabulary through the world press, film, and a play of the same name by Ernest Hemingway. For more, see the item in this collection Roosevelt’s Address on the “Fifth Column.”

- See Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, translated by Ralph Manheim, Sentry Edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943), 181. See also: Alan Axelrod, Selling the Great War: The Making of American Propaganda (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

- In April and May of 1940, Soviet secret police executed more than 20,000 members of the Polish intelligentsia and military officer corps. For more on the Katyn murders, see: J.K. Zawodny, Death in the Forest: The Story of the Katyn Forest Massacre (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015).

- On February 12-15, Allied bombers dropped several thousand tons of explosives on the city of Dresden, the capital of the German state of Saxony. Casualties are estimated at roughly 25,000 civilians. Contemporaries and later generations have debated the military utility of the attack, and some have even declared it a war crime. See: D.J.C. Irving, The Destruction of Dresden (Transworld, 1966); Jörg Friedrich, The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945, trans. Allison Brown(New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

- For more on African Americans in the war effort, see Andrew E. Kersten, “African Americans and World War II” in the Organization of American Historians Magazine of History, Volume 16, Issue 3, March 2002, 13-17.

- See the related item “Langston Hughes: Beaumont to Detroit, 1943.” For more on the parallels between Nazi and American race laws in the 1920s and 1930s, see: James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

- See the related item “NAACP Anti-Lynching Leaflet.”

- See the related item “Should I Sacrifice to Live ‘Half-American’?”.

- Nazi propagandists routinely attempted to sow division in the US Army by heightening racial tensions between white and African American servicemen.

- Monahan’s testimony can be found in Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States, Hearings Before a Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Fifth Congress, Third Session on H. Res. 282, vol. 2, (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1938), 1081-1096.

- See the newspaper coverage of Hull’s statement in “Hull Assails Czech Killing as Bestiality,” The Washington Post, June 13, 1942, 18; “Hull Denounces Slaughter,” The New York Times, June 13, 1942, 5.

- George Gallup, “The Gallup Poll: American Public Wants Harsh Treatment for Hitler and Nazi Leaders After the War,” The Washington Post, July 1, 1942, 15.

- W.H. Lawrence, “President Warns Atrocities of Axis Will Be Avenged,” The New York Times, August 22, 1942, 1.

- Carl Sandburg, “Wherever Free Men Fight They Will Remember Lidice,” The Washington Post, July 5, 1942, 7.

- See Ben Shahn, The Shape of Content (New York: Vintage Books, 1957), 47-48.

- George Creel served as head of the Committee on Public Information (CPI), established by President Woodrow Wilson in April 1917. Creel and the CPI were tasked with “building morale, arousing the spiritual forces of the Nation, and stimulating the war will of the people.” George Creel, Complete Report of the Chairman of the Committee on Public Information (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1920), 40.

- George Creel, How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information that Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1920), 133-134.

- See Brennan’s “Note to American Artists,” Archives of American Art, Ben Shahn papers, 1879-1990, bulk 1933-1970, Series 2, Letters, 1929-1990, US Office of War Information, 1942-1943.

- Bernard Perlin (1918–2014) was born in Richmond, Virginia. The son of Russian Jewish immigrant parents, he received his training in art at the New York School of Design, the National Academy of Design, and the Art Students League in the 1930s. Shortly after the United States entered World War II, Perlin joined the OWI, America’s official propaganda agency. From 1942 to 1943, he designed and laid out posters supporting the war effort, including “Let ‘Em Have It: Buy Extra Bonds.“

- William L. Bird, Jr. and Harry. L. Rubinstein, Design for Victory: World War II Posters on the American Home Front (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 27-28.

- Young & Rubicam Inc., How to Make Posters That Will Help Win the War, 1942. A copy of this report can be found in Archives of American Art, Ben Shahn papers, 1879-1990, bulk 1933-1970, Series 2, Letters, 1929-1990, US Office of War Information, 1942-1943.

- See page devoted to four basic findings in Young & Rubicam, Inc., How to Make Posters That Will Help Win the War, 1942-1943.

- The artist responsible for the striking and richly colorful image, Herbert Martin Stroops, went on to become an illustrator for popular magazines—Liberty, Collier’s, and The Ladies’ Home Journal—after the war.

- For more on Americans’ attitudes and responses to the Nazi threat, see the online exhibition Americans and the Holocaust.

- Although neither the US Postal Service nor the US Customs Service had kept complete records on the amount of Nazi propaganda entering the country, it supplied the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) with some alarming statistics. One Japanese ship alone transported almost five tons of German materials to the West Coast in a single trip. The Committee reported that additional Japanese freighters had dropped off nearly 10 tons of propaganda from one German publisher over the course of 12 weeks in fall 1940. See Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Eighth Congress, First Session on H. Res. 282, Appendix—Part III, Preliminary Report on Totalitarian Propaganda in the United States, (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1941), 1383–1384.

- For the activities of the Fichte-Bund in other countries, see Nick Toczek, Haters, Baiters and Would-Be Dictators: Anti-Semitism and the UK-Far Right (London: Routledge, 2016), 240–241; Martin Franzbach, “Deutsche Feindpropaganda nach Spanien und Lateinamerika im I. und II. Weltkrieg,” Iberoamericana, 14, no. 1 (1990): 26–e32; Mark M. Hull, “The Irish Interlude: German Intelligence in Ireland, 1939–1943,” The Journal of Military History, vol. 66, no. 3 (July, 2002), 695–717, 698–700; R. M. Douglas, “The Pro-Axis Underground in Ireland, 1939–1942,” The Historical Journal, vol. 49, No, 4 (2006), 1155–1183.

- See information on the Fichte-Bund’s activities in Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Seventy-Eighth Congress, First Session on H. Res. 282, Report on the Axis Front Movement in the United States, First Section—Nazi Activities, Appendix—Part VII), (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1943): 35; on the efforts of the Nazis on American college campuses, see Stephen H. Norwood, The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Stephen H. Norwood, “Legitimating Nazism: Harvard University and the Hitler Regime, 1933–1937,” American Jewish History, 92, no. 2 (June 2004), 189–223.

- James C. Clark, “Robert Henry Best: The Path to Treason, 1921–1945,” Jounalism and Mass Communication, vol. 67, no. 4: 1051–1061.

- See transcript of shortwave broadcast by Robert H. Best, May 25, 1943, in National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), RG-65, Files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Box 78, 100-Ha 103780, Sec. 2, Series 71-150.

- See Best’s broadcast of May 20, 1943 in NARA, RG-65, Files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Box 78, 100-Ha 103780, Sec. 2, Series 71-150.

- Robert H. Knapp, “A Psychology of Rumor,” The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Spring 1944), 22-37, 28.

- United States Office of Facts and Figures, Divide and Conquer (Washington, DC: Office of Facts and Figures, 1942), 4.

- Knapp, “A Psychology of Rumor,” 24.

- Clyde R. Miller, “Foreign Efforts to Increase Disunity,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 223 (Sep., 1942), 173-181, 173.

- The falsification of “atrocity stories” in the First World War—designed to align the US public behind the war effort—led to widespread suspicion of such accounts in the following decades. See other sources in our collection on American propaganda during the war. For more information on the creation, circulation, and proliferation of these images, see Barbie Zelizer, “From the Image of Record to the Image of Memory: Holocaust Photography, Then and Now,” in Bonnie Brennen and Hanno Hardt, eds., Picturing the Past: Media, History, and Photography (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999) 98-121.

- See USHMMA Acc. 2012.16.1, Irving P. Eisner collection. See also Leah Wolfson, Jewish Responses to Persecution, Volume V, 1944-1946 (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), 55-58.

- Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman, eds., Holocaust and the Moving Image: Representations in Film and Television since 1933 (London: Wallflower Press, 2005), 33-43.

- This term dates back to the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), and is attributed to Nationalist general Emilio Mola who reportedly announced that he was sending four military columns to advance on Madrid and had one column of sympathizers and agents operating inside the city to aid the revolt. It quickly entered into the popular vocabulary through the world press, film, and a play of the same name by Ernest Hemingway.

- Roosevelt reiterated the message of his May 26, 1940 television broadcast in a radio address that day. See “Fireside Chat on National Defense,” May 26, 1940 in Nothing to Fear: The Selected Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1932—1945, ed. Ben D. Zevin, (New York: Popular Library, 1961), 215-224. For more on Roosevelt and the question of a potential US entry into the war, see Steven Casey, Cautious Crusade: Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Public Opinion, and the War Against Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

- See Press Conference Held with Representatives of the American Youth Congress in the State Dining Room of the White House, June 5, 1940, 8:50 pm.

- In the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, more than 110,000 people with Japanese heritage—the majority of them American citizens—were imprisoned indefinitely in internment camps. For more on Japanese internment, see also the Densho documentary project.

- See the entry for Saturday, June 15, 1940, in The Secret Diary of Harold L. Ickes, vol. III (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1955), 208-212.

- On the German Teacher’s Association, see Marjorie Lamberti, “German Schoolteachers, National Socialism, and the Politics of Culture at the End of the Weimar Republic,” Central European History, 34 no. 1 (2001): 53–82.

- See Fred C. Koch. The Volga Germans: In Russia and the Americas, From 1763 to the Present (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977), 152; and La Vern J. Rippley, “F. W. Sallet and the Dakota Freie Presse.” North Dakota History, 1992, 2–20, as seen in F.W. Sallet and the Dakota Freie Press, Germans from Russia Heritage Collection.

- September 1, 1939 also marks the first day of World War II.

- For more on the role of propaganda in Hitler’s foreign policy before World War II, see Gerhard Weinberg’s essay, “Propaganda for Peace and Preparation for War,” in Germany, Hitler, and World War II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 68–82. See also the collection Propaganda and the American Public.

- The Seventh-Day Adventist Church is a Protestant denomination that emerged in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. It shares similar teachings with other traditions, such as Baptists and Methodists, but has several distinctive elements, most notably observance of the Sabbath (Saturday) and its emphasis on diet and healthy lifestyles. Adventists first went to Germany in the 1880s and by the 1930s, it was one of the largest independent churches in Germany with a membership of 38,000. It was engaged in extensive welfare work and in the Nazi period became an approved organization of the National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV), along with the Salvation Army and a number of other German organizations that provided social services.

- Roland Blaich, “Selling Nazi Germany Abroad: The Case of Hulda Jost,” Journal of Church and State 35 (1993): 807–830.

- See the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s special exhibition Americans and the Holocaust for examples of OWI posters. See also the related Experiencing History collection, Propaganda and the American Public.

- This photo is part of a larger collection created by the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information, available at the Library of Congress. The prominent minister Henry Smith Leiper, an author of another document in this collection, spoke at the exhibit’s opening in May of 1943.

- Gauleiter:German, a term referring to a regional leader of the Nazi Party.

- The so-called Axis represented the coordinated military aims of Italy, Germany, and Japan during World War II.

- For more on the effects of Nazi propaganda in the US, see the Experiencing History collection Propaganda and the American Public. For more on German exchange students spreading Nazi propaganda on American campuses, see Stephen H. Norwood, The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- The Third Reich also sponsored trips to Germany for American students and professors in the 1930s. See the related items in Experiencing History Dr. Fritz Linnenbuerger: “Trip to Germany” and Carl Schurz Tour of American Professors and Students through Germany in Summer 1934.

- The article was originally published in The Columbia Missourian on September 28, 1937.

- Noelle socialized with her fellow students and actively participated in university life. She played accordion, sang German folk songs, and attended sorority events and meetings of the university’s German club.

- The activities of Noelle and the other German exchange students at the University of Missouri came to the attention of the United States House Un-American Activities Commission (HUAC), which formed in 1938 to investigate allegations of subversive activities in the US. In 1938, HUAC called the University’s president to testify about Nazi exchange students and propaganda on the University of Missiouri campus. See United States House of Representatives Special Committee on Un-American Activities, Investigation of Un-American Propaganda Activities in the United States, vol. I (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1938), 1134–1137.

- For more details, see “Professor Is Criticized for Anti-Semitic Past,” New York Times (November 28, 1991), B16.

Originally published by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.