A lack of government regulations enabled strange “cures”.

Introduction

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, Americans were inundated with myriad medicinal treatments collectively known as patent medicine. At a time when doctors and medical clinics were less common, especially in rural areas, patent medicines promised relief from pain and chronic conditions when few other options existed. The term “patent medicine” referred to ingredients that had been granted a government patent; but ironically many purveyors of patent medicine did not register their concoctions with the government. As a result, many competitors offered similar formulas and freely imitated each other’s products.

The story of patent medicine is multi-layered. It is about the phenomenon of Americans self-medicating with opiates, alcohol, and herbal supplements, as well as women’s health and healthcare options. It follows the evolution of advertising in America and the rise of chromolithography printing techniques and newspaper advertisements. Finally, patent medicine reveals dubious scientific knowledge during a time when germ theory was in its infancy.

Patent Medicine, 1860-1920

Overview

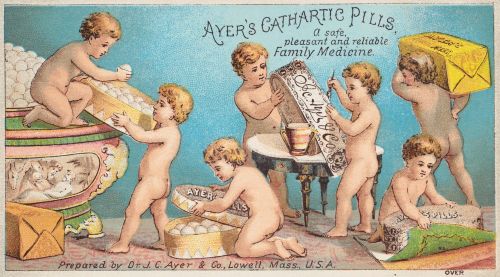

The so-called golden age of patent medicines lasted from the mid-nineteenth century into the first two decades of the twentieth century. By modern standards, Americans during this period knew very little about human physiology, biochemistry, and endocrinology. They sought quick solutions for medical problems that they did not necessarily understand. Doctors, when available, were not always to be trusted. Hospitals, where available, were often considered places where people went to die. Patent medicines offered quick, convenient, and inexpensive relief from arthritis, depression, and mental illness, as well as women’s problems, indigestion, liver problems, and lack of hair growth. Children were dosed with medicines to aid their growth, feed their blood, and facilitate the movement of their digestive tract.

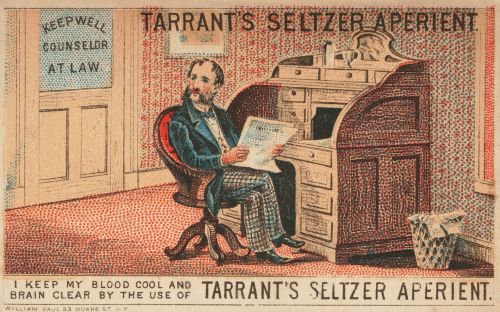

A lack of government regulations enabled the sale of drugs that contained opium, laudanum, paregoric, alcohol, tar, and other ingredients consumers would not consider ingesting today. Increased government regulation brought about the end of the patent medicine era. In 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, with the strong support of President Theodore Roosevelt. Although patent medicines continued to be produced after that date, new, stricter regulations demanded that ingredients be printed on labels, false claims be toned down, and advertising be more truthful. The legacy of this era lives on in today’s television infomercials for “miracle cleaning products” and “fast weight loss solutions.”

Opiates, Alcohol, and Herbs

Patent medicines often had the capacity to help people feel better. “Feeling better” was not necessarily the result of patent medicine’s medicinal properties; but rather related to the fact that many patent medicines were laced with opiate drugs and alcohol. Given the prevalence of these addictive ingredients, it is not surprising that many products were enthusiastically endorsed by their users. Patent medicine drugs were usually created from a mixture of vegetable compound with alcohol, morphine, opium, or cocaine. At this moment in US history, the medical profession did not recognize the dangers or addictive natures of opiates. As a result, many doctors advocated the use of cocaine and other drugs. Alcohol was included as a “preservative” ingredient; but the alcohol levels found in patent medicine could be as high as sixteen percent—the same alcohol level found in commercially-produced wine.

The prevalence of addictive ingredients combined with the drugs’ ready availability helped to create a culture of “self-dosing” or “self-medicating.” Beginning with the Mexican-American War in 1846 and later, during the American Civil War (from 1861 to 1865), the mid-nineteenth century saw an increase in communicable diseases which spread quickly and easily. Two-thirds of the soldiers who died during the Civil War perished due to disease, not battle wounds. Common camp illnesses included typhoid fever, ague fever, pneumonia, scurvy, malaria, tuberculosis, and smallpox. All of these diseases needed treatment or cures, and producers of patent medicines stepped in to provide solutions.

Product Range

Blind or Bleeding, Itching or Burning. One application brings relief. —Advertisement for Humphreys’ Homeo. Med. Company, New York

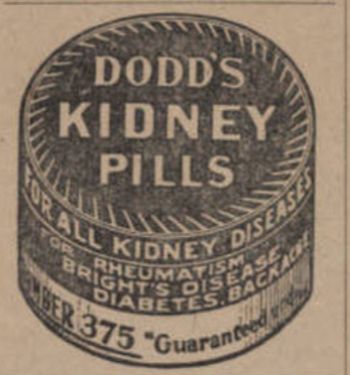

Pills, tonics, salves, and syrups made cure-all claims covering all kinds of ailments, from rashes and skin problems, coughs, and digestive troubles to melancholy, depression, and mental illness. Other concoctions included hair tonics that invigorated and restored hair growth as well as liniments for rheumatism and pills for neuralgia (severe headache pain).

Drugs were also developed to address conditions referred to as “female weakness” and “loss of manhood.” “Female weakness” could refer to a variety of health concerns, including postpartum depression, menopause, or menstrual cramps. “Loss of manhood” was a thinly veiled term for male impotence. There was a drug or tonic to address every ailment.

Women’s Health and Household Hints

Overview

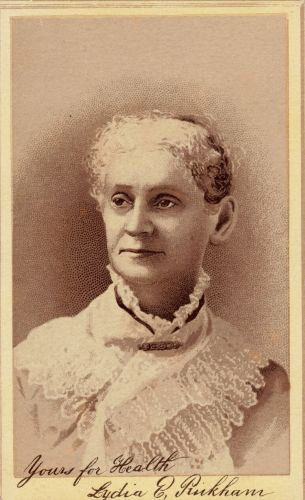

“Only a woman can understand a woman’s ills.” —Lydia Pinkham

Many patent medicine makers marketed products specifically to women. During this time, many American women were not comfortable talking and asking questions about their own bodies. Given that most doctors were men, many women were hampered by their own modesty and society’s sense of propriety. Furthered by the fact that some women living in rural or frontier America did not always have access to a doctor, patent medicines offered an opportunity to self-remedy. The privacy and convenience of patent medicines delivered by mail order addressed these issues.

The following list of women’s health issues were subjects that many women did not feel comfortable discussing.

• Puberty

• Menstruation

• Fertility

• Pregnancy

• Abortions

• Childbirth

• Postpartum Depression

• Menopause

When women did discuss these health concerns they often used euphemisms or veiled terms as opposed to more straightforward terms. For example, the term “maturation” was used for the onset of puberty and “the change” referred to the start of menopause.

Lydia Pinkham

“When we hear of so many school girls and girls in stores and offices who are so often unfit to perform regular duties because of some derangement peculiar to their sex, may it not be that their mothers have been careless and through neglect failed to get for these daughters the one great remedy for such troubles, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound?” —Lydia Pinkham Medical Company, 1920 pamphlet

Perhaps the most famous purveyor of medicines for women was Lydia Pinkham. Born Lydia Estes in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1819, she married Mr. Pinkham in 1843 and subsequently raised a family. It was not until later that she produced her famous “vegetable compound” that would change her life and elevate women’s concerns to a national level. This compound was concocted from a recipe her husband obtained as part of the payment of a debt. The concoction was marketed as a “women’s tonic” and was promoted as relief for menstrual cramps and the discomforts of menopause. Lydia Pinkham’s compound debuted in 1875 and eventually her entire family was involved in its production. Her children filled bottles and folded advertisements.

Pinkham’s business flourished long after her death in 1883. An image of her was included on the bottles and helped perpetuated her image as a hardy and resourceful New Englander who was also a woman that other women could trust. Pinkham’s image was also distributed directly to druggists in the form of advertising cards, souvenir plates, and gift items.

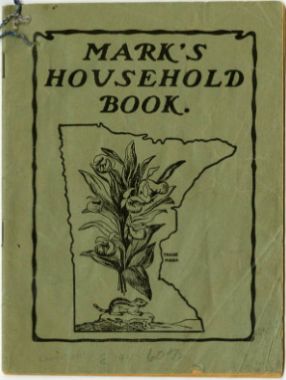

Household Hints

“Before the baby came, I was very dizzy and had blind spells. One of the neighbors told me to take your medicine. Since taking it, I am not so nervous and dizzy and I can do my work.” —Mrs. C. Burton, Chesapeake Beach, Maryland (from “Come into the Kitchen” by Lydia Pinkham)

In addition to addressing women’s medical needs, some patent medicine makers also offered a variety of informational pamphlets on home care and household hints. Recipes, advice on manners, home remedies, hygiene, canning, and food preservation were all topics covered in these publications. Interspersed among the pages of recipes were not very subtle product advertisements for herbal supplements, laxatives, and compounds to address “women’s concerns.”

These booklets were comprised of three elements: advertisements for the patent medicines, various types of household hints, and consumer endorsements. These consumer testimonials offered enthusiastic and dramatic endorsements of the patent medicine cures.

Advertising Methods

Overview

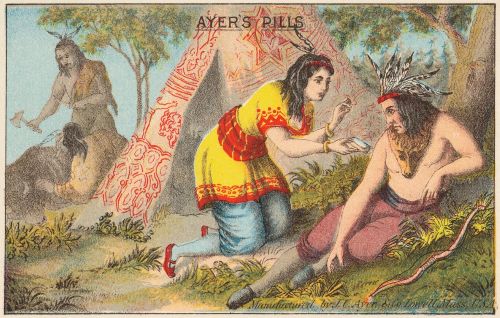

Patent medicine advertisements appeared in the back pages of American newspapers and magazines and were also distributed via pamphlets and full-color trade cards. Patent medicines were often sold via rigorous advertising campaigns. A number of themes consistently emerged in patent medicine advertising. These included images that portrayed Native Americans as purveyors of secret herbal remedies, images of “learned medical advisors” who were often scholarly-looking white men, and a large number of celebrity endorsements.

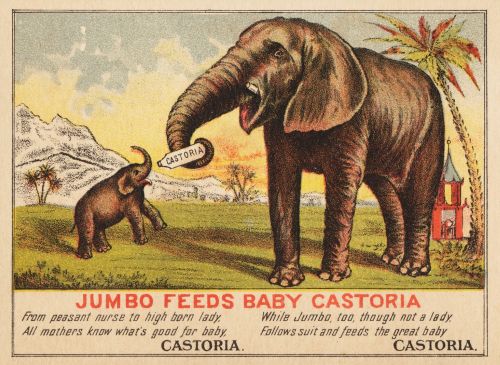

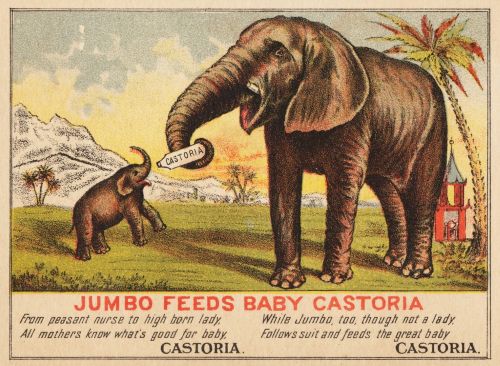

Various nineteenth century notables such as the reporter Nellie Bly, the actress Sarah Bernhardt and the widely-recognized Jumbo the Elephant all lent their names to various patent medicine concoctions. Patent medicine advertising also employed a number of gimmicks to ensure repeat customers. These included giveaways such as pamphlets and cardboard novelties, games, jokes, cartoons, and puzzle cards.

Newspaper Advertisements

The nineteenth century brought sweeping changes to communication in the United States, including the invention of the telegraph and the explosion of newspaper circulation. In 1800, there were 200 newspapers published in the United States. By 1860, the number had increased to 3,000, and by 1900, the number had exploded to more than 20,000. This large group included the weekly newspapers produced by small, rural communities, political newspapers, ethnic newspapers produced by America’s various immigrant groups, and niche papers that were produced for specific markets such as farmers, gardeners, fraternal organizations, and Sunday-school students. It also included the large daily papers produced by newspaper moguls such as William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, and others.

This expansion of American newspapers has been attributed to a variety of factors, including a rise in literacy, advances in printing and papermaking, and increased leisure time. More people were reading; and more people were reading about patent medicine in their local newspaper. As the number of newspapers increased, so did newspaper advertising. In turn, newspaper advertising played a large role in the dissemination of information about patent medicines.

Chromolithography Advertising

The chromolithography printing process brought huge changes to American advertising. It allowed full color images to be cheaply and easily applied to metal and paper. The result was the creation of brightly-colored tea, biscuit, and tobacco tins, as well as color postcards and holiday cards. Full-color book illustrations, calendars, and almanacs were also in widespread production.

In addition, the chromolithography process generated large numbers of advertising or trade cards. Trade cards leveraged the new printing process to its full advantage. Images of beautiful women and children, flowers, cats and dogs, and bucolic landscapes were added to labels to help sell various products.

Stock Cards and Advertising Cards

The production and prevalence color trade cards of the nineteenth century gave rise to a phenomenon called the “card craze,” which began in the 1870s and continued into the early twentieth century. This popular pastime inspired Americans to collect and display advertising promotions. Trade cards promoted a large range of products from household goods, soaps, flower and vegetable seeds, to tobacco and patent medicines. Many of these cards were collected, traded, and pasted into scrapbooks.

Color card advertisements typically took one of two forms: stock cards or advertising cards. A “stock card” was a pre-printed card that often featured flowers, landscape scenes, or comic images. These cards were then imprinted at a later date with an individual retail merchant’s name and address. Frequently the advertising image bore little or no relationship to the product being sold. As a result, patent medicine stock cards could feature images of kittens, babies, and floral arrangements. Also in common production were “advertising cards.” Advertising cards were printed for a single, specific product.

Animals in Advertising

Overview

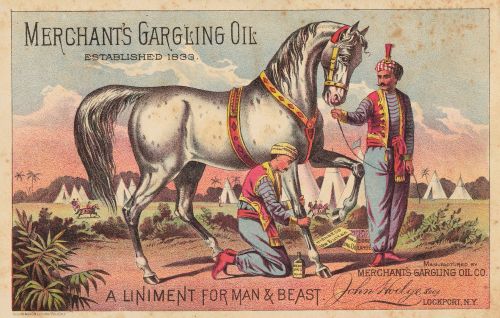

“The Great External Remedy for Man or Beast.” —Patent Medicine advertisements

Images of animals were often featured in patent medicine advertisements. Some products leveraged the “cute factor” of animals and used kittens, puppies, and birds to promote a wide variety of products. Manufacturers used images of celebrity animals, such as Jumbo the Elephant, to promote everything from thread and coffee to patent medicines. Images of livestock animals, such as horses, cows, and pigs, were also used to promote concoctions that could be used to treat medical problems shared by humans and animals.

Some patent medicine makers created tonics that they promoted as appropriate for all creatures living on the farm. According to them, horses, cattle, and humans faced similar (if not identical) medical issues. Eye problems, rheumatism, coughs, and skin irritations were common to both humans and animals, and these remedies were marketed as providing relief to either “man or beast.” A number of contextual factors made these ideas believable: the convenience of buying a single preparation, a lack of knowledge about the differences between human and animal physiology, and the affordability of the medicines. In a time when both human and animal diseases were less well understood, it is not surprising that some individuals assumed that generic medications could work across species.

Darwin’s Grandpapa

“If I am Darwin’s grandpapa… what is good for man and beast, is doubly good for me.” —Merchant’s Gargling Oil slogan

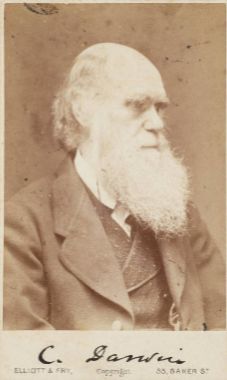

Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution in 1859. On the Origin of Species was a groundbreaking work that was eventually translated into many languages and widely disseminated to both popular and scientific communities. It became a foundational text in the study of biology, but the work was not without its detractors. Victorian England and nineteenth-century America manipulated Darwin’s work into caricatures and cartoons that lampooned the concept of a shared human and animal ancestry. Animals were shown with human traits and humans were shown with animal traits. For some, this type of imagery popularized Darwin’s theory in an unthreatening way, while for others, these images trivialized Darwin’s serious scientific work.

The use of combined animal/human imagery was leveraged by several patent medicine creators. Merchant’s Gargling Oil (“A liniment for man or beast!”) presented a generic species of great ape as “Charles Darwin’s Grandpapa.” These images promoted the use of some drugs as appropriate for both human and animals based on a pseudo-scientific connection and a distortion of Darwin’s work.

Jumbo the Elephant

Jumbo the Elephant was one of the world’s first animal superstars. Born in East Africa in 1862, the young elephant was captured and sent to Europe, where he was the first captive African elephant to live into adulthood. Eventually Jumbo was brought to England by the London Zoological Gardens. Jumbo lived at the London Zoo for sixteen years and was a favorite of both children and adults. Jumbo was the single largest elephant in captivity and the American showman and circus-owner, P. T. Barnum, wanted Jumbo for his own. Barnum purchased Jumbo in 1882 and brought the elephant to America. Jumbo’s arrival in the United States ushered in an era of “Jumbo-mania,” in which all things related to Jumbo the elephant were wildly popular. The American consumer market were flooded with thousands of images of Jumbo endorsing thread, birthday cards, candy, clothing, jewelry, soap and various patent medicines.

Jumbo was killed by a Grand Trunk Freight Engine in Ontario, Canada in 1885. In typical Barnum fashion, P. T. announced Jumbo’s death as a “hero’s death,” and he promoted the idea that Jumbo gave his life to save that of a baby elephant. Jumbo’s legacy lived on long after his death. He was the single most popular animal used in advertising images. From sewing thread to Castoria Oil, Jumbo’s image was used to sell products. The Castoria Oil advertisements, for example, feature an image of Jumbo in a fictional jungle setting where he was raised on Castoria Oil, and as a result, grew big and strong.

Racial Stereotypes in Advertising

Overview

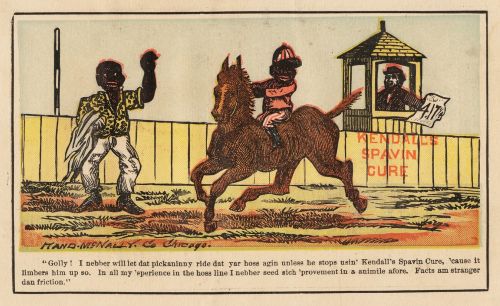

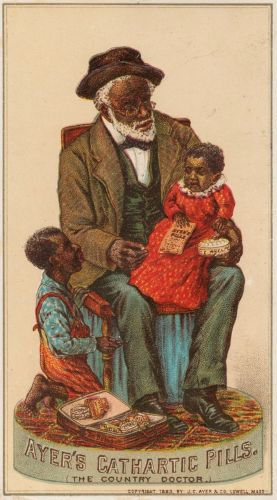

Patent medicine advertising, and nineteenth-century advertising in general, helped to perpetuate popular American racial and cultural stereotypes of the period. In addition, the chromolithographic process was ushering in a new era in American advertising. Full color images depicting caricatures and other stereotypical material delivered messages with an even greater impact than simple line drawings or text-based newspaper advertisements.

Two groups were frequently targeted: African Americans and Native Americans. Advertisers employed stereotypical images of subservient black Americans featuring exaggerated dialect and facial features. They presented Native Americans as “noble savages,” a type exemplified by the iconic cigar store Indian and used to sell a wide of products, including patent medicine.

African Americans

From the mid-nineteenth century well into the twentieth century, African Americans were frequently portrayed derogatorily in American advertisements. Advertisers often depicted blacks as slaves subservient to white people. Racial stereotypes took the forms of Aunt Jemima, Little Black Sambo, and Jim Crow. Black Americans were sometimes represented with exaggerated facial features, such as large lips and bulging eyes. Another stereotype presented African Americans as country folks with a fondness for watermelon and fried chicken and showed them barefoot and dressed in “rough country clothing,” like overalls and straw hats.

These images often showed African Americans offering advice to white people in a deferential manner. African Americans were also presented in cartoons with “humorous anecdotes” in which the joke hinged on the reader’s understanding of the gullible or simple nature of black characters—discriminatory cultural assumptions of the period that today read as racially charged defamation. These images were pervasive and served not only to promote a vast array of consumer products, but also helped to perpetuate negative attitudes and opinions.

Native Americans

Native Americans were also portrayed derogatorily in American advertisements. In patent medicine advertising, they were presented as the “Noble Red Men” who provided “natural” remedies to the rest of the world. This stereotype bolstered a belief in natural, botanic remedies and was directly tied to nineteenth-century America’s hostility toward modern medicine and distrust of doctors. Native Americans were portrayed as “natural healers” and “Mother Nature’s Physician.” This stemmed from common beliefs that Mother Nature could provide medicine to cure all of humanity’s ills and that Native Americans were innately primitive and connected to the natural world.

The following list includes just some examples of pseudo-Native American products:

• Dr. Morse’s Indian Root Pills

• Ka-Ton-Ka Nature’s Gift to Nature’s Children

• Indian Vegetable and Animal Salve

• Dr. Newall, the Native Indian Doctor

• Dr. Kilmer’s Indian Cough Cure

• Kickapoo Indian Medicine Company

Drugstores

Overview

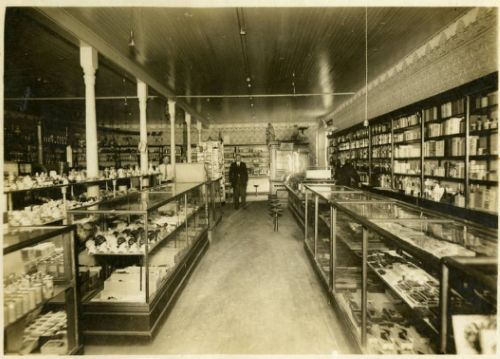

“Anyone with enough courage and capital could open up a drugstore.” —Gregory J. Higby, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy

The drugstore as we currently know it evolved during the nineteenth century. Prior to the Civil War, American pharmacists worked in storefronts. These small establishments sold only drugs and medicines and pharmacists placed their drug compounding supplies near the front door.

By the late 1800s, a new type of retail space was developed to sell both prescription and patent medicines. Now, the drugstore also included additional consumer products beyond medications, including magazines, candy, stationery, and cosmetics. The growth of the American drugstore eventually prompted a rearrangement of the space to accommodate a growing consumer market. The pharmacist and medicines were moved to the back of the store and other more profitable products such as tobacco, candy, and the soda fountain now occupied the prime real estate in the front and center of the store.

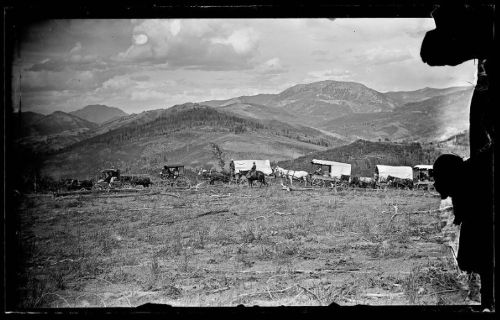

Frontier America

The nineteenth century witnessed a huge migration of settlers into the American frontier. With the promise of a freedom, cheap land and a new life, people headed west. The settlement of the American West gave rise to countless small towns during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of these settlements lacked access to doctors and hospitals; but eventually many of these towns featured a drugstore. The addition of the drugstore helped the spread of patent medicine across the United States.

The corner drugstore was not just a pharmacy. Drugstores on the frontier frequently sold a wide array of products and were the convenience stores of their time. In addition to pharmaceuticals and patent medicines, drugstores also sold household goods, furnishings, cleaning supplies, greeting cards, and beauty and hygiene products. As the years passed, drugstores began selling food items like crackers, cookies, and candy. The invention of the soda fountain helped to secure the drugstore’s place in a community as both a retail store and a social destination.

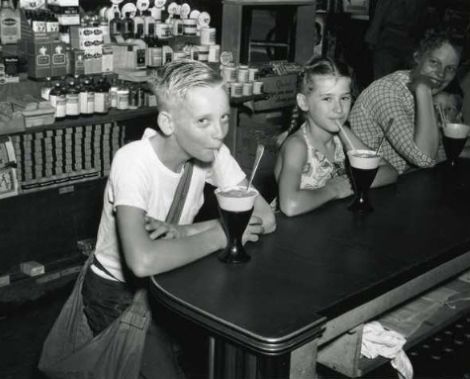

Soda Fountains: The Pharmacist’s Creation

By the late 1800s, many drugstores featured soda fountains. The soda fountain leveraged the pharmacist’s practical knowledge of chemistry. This knowledge of chemistry and chemical reactions allowed for the creation of drinks that combined syrup concentrate, ice cream, carbon dioxide, and water. The result was flavored sodas, sundaes and ice cream sodas, and treats like the banana split, which was invented by a pharmacist in Pennsylvania. Early pharmacists were also instrumental in the creation of commercial soft drinks. Some of modern America’s most popular soft drinks were created by pharmacists. Coca-Cola was invented by John Pemberton, a pharmacist in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Pepper was the creation of Charles Alderton, a pharmacist working at the Old Corner Drug Store in Waco, Texas.

The invention of the soda fountain and the changes in the drugstore’s layout signaled a larger change. Drugstores were no longer just purveyors of prescriptions and patent medicines, but rather were expanding their role as purveyors of both medicinal and novelty goods. The soda fountain as a destination—for first dates, special outings, or just a cool treat on a hot day—made many drugstores the social centers of their communities.

Made in Minnesota: Patent Medicine on the Prairie

Overview

Many states became regional hubs for patent medicine production. A number of companies were based in Ohio, including Samuel Hartman’s Peruna Drug Manufacturing Company. Massachusetts was the home base for both Dr. Ayer and the Lydia Pinkham Medical Company.

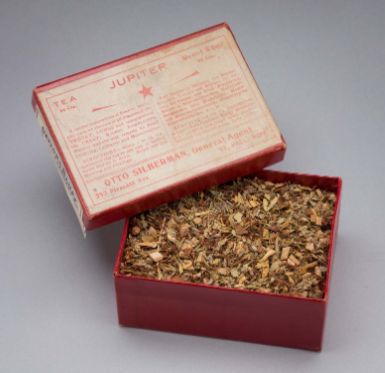

Minnesota was also part of this phenomenon. Home to the nationally-known J. R. Watkins Company, Minnesota also boasted a number of other producers, including Mark’s Medical Company located in Fosston and the smaller Fluid-d’Or Company of Hibbing, Minnesota. Together these and other start-up companies helped to put Minnesota on the patent medicine map and contributed to the young state’s growing economy.

J.R. Watkins Company, Winona, Minnesota

“When you deal with a Watkins’ agent, you patronize a reliable man.” —J. R. Watkins Company slogan, 1904

The J. R. Watkins Company was founded by J. R. Watkins in 1868 in Plainview, Minnesota. Watkins concocted products which he began selling door-to-door. The company moved to Winona, Minnesota in 1885. In the late 1800s Winona was a thriving lumber town, conveniently located on the Mississippi River. By the early twentieth century, the Watkins Company was one of the largest direct-sales companies in the United States.

The Watkins product line began in 1868 with the original J. R. Watkins Liniment made with camphor from pine trees and capsicum from red peppers. It is still sold today for the relief of minor muscle aches, soreness, and stiffness. Eventually the product line expanded to include baking ingredients and spices, as well as bath soaks, cough rubs, menthol drops, vitamin supplements, and cleaning supplies.

The Watkins Man

“You can have opportunities limited only by your own personal ambition, willingness to work and ability to follow our practical guidance!” —”The Open Door to Success,” J. R. Watkins Company promotional booklet

The direct-sales model used by the Watkins Company gave rise to the door-to-door salesman known as “the Watkins Man.” The Watkins Man was a traveling salesman who journeyed through America’s back roads via horse and wagon and later with an automobile. This model offered direct sales to the customers, as well as independence and autonomy for the Watkins employee. The Watkins Company prided itself on the knowledge that the Watkins Man knew his customers personally and selected products to meet their needs.

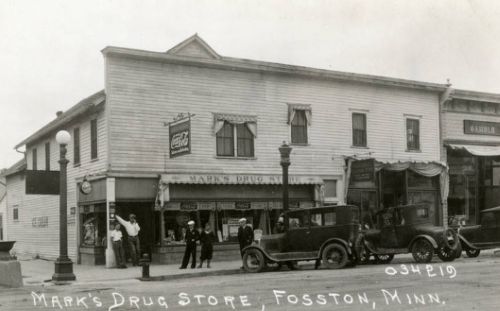

Mark’s Drug Company, Fosston, Minnesota

“The dull days, the restless nights, the disturbances of digestion, the condition known as “out of sorts,” are the evidences that health has slowed us down.” —Mark’s Household Book of Valuable Information

The Mark’s Drug Company of Fosston, Minnesota, was headed up by Dr. Peter Mark, a licensed pharmacist. Dr. Mark arrived in Fosston in 1892. At that time, Fosston was literally at the “end of the line,” as it was the terminus of its railroad line. Dr. Mark used this location to his advantage. By setting up business on the frontier, he was able to reach a new brand of consumers: railroad workers, loggers, and lumber men.

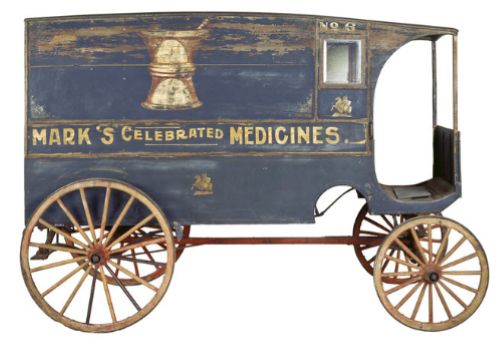

In addition to providing wholesale pharmacy supplies, he also compounded a variety of patent medicines in a factory he set up in a former bank in downtown Fosston. This “Mark’s Medicine Factory” produced wares that were sold directly out of his drugstore as well as being distributed to rural areas via his specially built wagons. Salesmen visited small railroad towns, logging camps, and rural settlements using these sturdy wagons.

Products of Mark’s Drug Company

“Mark’s Lung Balsam with Tar. For the cure of all diseases of the lungs, throat and chest, such as Cough, Cold, Asthma, Bronchitis, La Grip and will prevent Consumption when taken in time.” —Mark’s Household Book of Valuable Information

Mark’s Drug Company offered a wide variety of products. In addition to more dubious patent medicine concoctions, the company also produced and sold more standard medical supplies like cough syrup, quinine capsules, and denatured alcohol.

Among Mark’s most notable patent medicines were the celebrated “Mark’s Kidney and Liver Balsam” and the “Lung Balsam with Tar.” Other remedies included:

• Little Liver Pills

• Itch Cure

• Hair Oil

• Strengthening Drops

• Eye Salve

• Dr. Bendeke’s Eye Water

• Kill Pain Porous Plasters

• Mark’s Sewing Machine Oil

• Goodie’s Barbwire Liniment

• Physic Capsures for Horses

Mark’s delivery wagons were emblazoned with slogans and the reminder, “If your dealer does not carry this medicine, write P. M. Mark, Fosston, Minnesota!”

This exhibition was created as part of the DPLA’s Public Library Partnerships Project by collaborators from Minnesota Digital Library. Exhibition organized by Greta Bahnemann.

Published by the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), September 2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.