The “lifestyle” genre between 1500 and 1570.

By Dr. Peter van der Coelen

Curator of Prints and Drawings

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

By Friso Lammertse

Curator of 17th-Century Dutch Painting

Rijksmuseum

By Lynne Richards

Freelance Translator

Lynne & Paul Richards Translations

Introduction

“Painting is used in the service of the church to show the sufferings of Christ and many other good images and it also preserves the likenesses of people after they have died.”1 Albrecht Dürer wrote these words in 1513 in an introduction for aspiring artists. By then he had already visited Italy twice but had not yet journeyed to the Low Countries. It was not until 1520–21 that he traveled westward, and in cities like ’s-Hertogenbosch, Bruges, Brussels, Ghent, Mechelen, and, above all, Antwerp, saw the latest developments in visual art. Dürer’s essay might well have been longer had he embarked on it after this trip. He would probably have acknowledged that painting was not confined to representations of the Passion and portraits, but that it could also render landscapes and scenes of everyday life. In Antwerp he met Joachim Patinir several times (he even attended his wedding) and was presented with a small panel painted by him (fig. 1). “The good landscape painter,” he noted in his diary about this artist, who was the first to make landscape the main subject of his panels.2

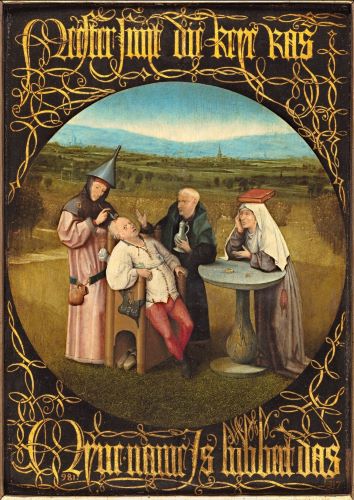

Equally new was the idea of taking everyday life as a subject. This had been going on for more than fifty years in prints—Dürer himself had made a major contribution to the medium—but it was completely new in panel painting. In the first quarter of the sixteenth century, three painters took the lead in this field: Hieronymus Bosch, Quinten Massys, and Lucas van Leyden. Bosch had died four years before Dürer visited ’s-Hertogenbosch, but without doubt his works would have been everywhere. It is even possible that his workshop was still active, where such paintings as Cutting the Stone and The Conjurer (figs. 2, 3) may have been produced.

In Antwerp, the German artist visited Quinten Massys’s house, although he does not appear to have met the painter himself. He most likely saw one or more of Massys’s genre scenes in his studio, and he would in any event certainly have seen such works in the houses of the town’s wealthy burghers by whom he was entertained (figs. 4, 5). He saw the third great pioneer in person. The “kleins männlein” (little man) Lucas van Leyden may well have traveled from his home town of Leiden to Antwerp specifically to meet the great master of engraving.3

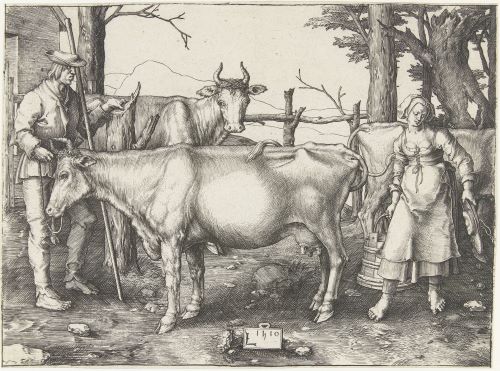

They exchanged prints, and it is intriguing to think that Lucas might have shown him his Milkmaid, a completely new subject in art (fig. 6).

And while Dürer was making his portrait, the Leiden artist may have told him about his small panels with such equally original subjects as chess players and card players that he had been making for more than ten years (fig. 7).It is perhaps difficult for art lovers today to realize just how extraordinary a step Bosch, Massys, and Lucas van Leyden were taking. Nowadays the autonomy of art can be considered its defining feature, but five hundred years ago it was almost inconceivable that painting should depict anything but religious stories and portraits. The step that the three took was consequently a cautious one. Only a small proportion of their works deal with everyday life, by far the majority are tales from the Bible and the lives of the saints. The link between church and art was so much a matter of course that it was to take several generations before everyday scenes ceased to be the exception and became a generally recognized and accepted subject. This exhibition explores the first cohort of painters and printmakers who developed the new genre between, roughly, 1500 and 1570. This was a timespan bracketed by two of the most exceptional artists the Low Countries have ever produced: Hieronymus Bosch at the beginning and Pieter Bruegel the Elder at the end. But alongside them was a whole host of well-known and less familiar artists, such as Jan Sanders van Hemessen, Marinus van Reymerswale, the Brunswick Monogrammist, Jan Vermeyen, Pieter Aertsen, Joachim Beuckelaer, Peeter van der Borcht, and, of course, Quinten Massys and Lucas van Leyden, who first gave shape to the depiction of everyday reality and ensured that it would ever after be an indispensable part of visual art.4

The Concept of Genre

These artists were undoubtedly aware that they were doing something new, but they would never have dreamt that one day they would be grouped together as the originators of a new subject in art. It is only with knowledge of the developments in visual art in the centuries thereafter that their work acquires cohesion. In retrospect the roots of such countless specialties as landscape, still life, and genre prove to lie in the sixteenth century. But Joachim Patinir could not possibly have suspected that his decision to subordinate his figures to the landscape would lead to painters who would specialize in scenes of skaters on the ice a century later, let alone have had an inkling that it would lead to Impressionism three hundred and fifty years on. And Hieronymus Bosch could never have imagined that his Pedlar (fig. 8) marked the start of a road that would lead to the realism of Gustave Courbet’s 1854 The Encounter (Bonjour, M. Courbet) (fig. 9).

Of all the specialties in art that have crystallized since the sixteenth century, genre is the most diverse and the hardest to define. Genre did not become the accepted term to describe a (seemingly) everyday scene until the nineteenth century.5 Subjects as wide-ranging as a tax collector, a peasant celebration, children playing, and a brothel were brought together under a single heading. In the sixteenth century, no one would ever have thought of grouping such disparate themes. People described scenes as “a kitchen” or “a peasant fair” and that was that. The need to organize them could not come about until such time as considerable numbers of works like this had been made, and that happened only at the end of the century, initially in printmaking. Collectors started to think up separate categories into which they could sort the everyday subjects in their print albums but never with particularly strict criteria.6

In genre works, human figures always play an important role, but they are anonymous and intended to be so.7 These works are not illustrations of a historical, biblical, or mythological event. In the sixteenth century, genre compositions were always constructs. The artist did not look out his window and paint what he saw onto his panel. When we refer hereafter to everyday, daily, or ordinary life, we never mean a snapshot, in the sense of a photographic snapshot. The composition creates the suggestion that it is realistic, but this does not mean that what was depicted was a common occurrence. In the sixteenth century artists were particularly fond of emphasizing the comical and satirical with caricatured faces and old-fashioned dress. Too stringent a definition of the different genres of still life, landscape, allegory, and history painting, as often used today, is meaningless. As we have said, such categorizations did not exist at the time, and for a better understanding we need to look at works that would be grouped under a different heading nowadays. An attractive, anonymous young woman playing a lute is, of course, a genre scene (fig. 10).

But when a woman who looks very similar has a jar of ointment on the windowsill she becomes Mary Magdalene (fig. 11).

The same occurs in the brothel scenes that were so popular in the sixteenth century. In one case it really does appear to be a sixteenth-century whorehouse (fig. 12).

But in a virtually identical work, a view through a colonnade reveals a man sitting with swine, which turns it into the parable of the Prodigal Son (fig. 13). It is evident that the one cannot be understood without the other. We have, though, placed an emphasis on purely profane compositions, out of a conviction that they comprise the more essential step. Some works by Herri met de Bles and, for that matter, Pieter Bruegel in which everyday human activities play an important role would now most likely be classified as landscapes.

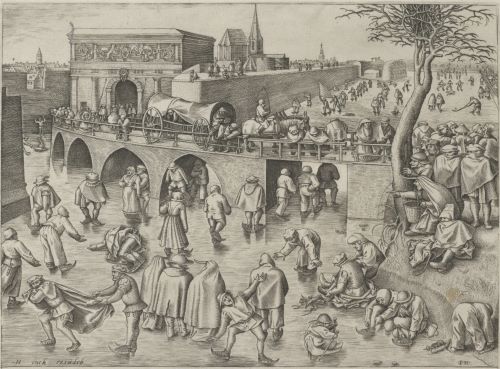

Particularly in landscapes, artists seemed to pay less heed to pictorial traditions when they populated them with genre-style scenes. They presented previously unseen subjects that must have opened other artists’ eyes to new possibilities. No one could doubt that Bruegel’s snowy landscape with dozens of skaters was of immense importance to the future development of genre art (fig. 14).

Forerunners

What the three pioneers did was radically new, but their work was rooted in various traditions. Crucial to the development of genre painting was what happened in printmaking from the mid-fifteenth-century onward in the Low Countries and, even more, in the German Rhine region. For this reason the engravers of the generations before Bosch, Lucas, and Massys are examined first in the exhibition. These anonymous printmaking pioneers, who had greater freedom in their choice of subjects from the outset, have been given names of convenience—Master E.S., the Master of the Housebook, and Master FVB.

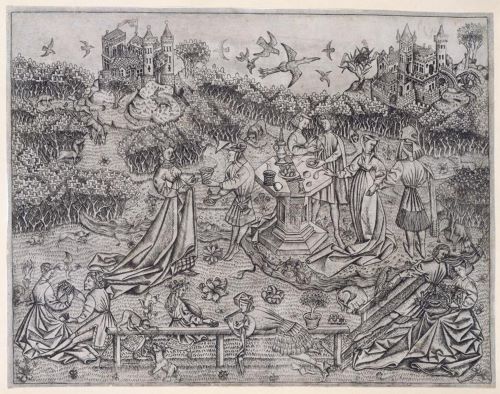

Everyday scenes must also have been depicted in paintings for some time, but precisely how and to what extent remains unclear. At the end of the fourteenth century a prelate in Wiesbaden had the walls of a room in his house decorated with a series of unusual scenes. There were feasts, tournaments and battles, the sufferings of the peasants, and a local bath house in which soldiers and religious figures of both sexes disported themselves. They have long since disappeared and we only know of them thanks to a contemporary description.8 There must have been similar decorations in other houses and palaces in Germany and in the Low Countries, too, but none has survived. The description reveals just how fragmentary our image of medieval painting actually is. It also reminds us that genre scenes painted on panels after 1500 did not suddenly appear out of nowhere. Fourteenth- and fifteenth-century ivories, tapestries, and miniatures that have survived tell us which everyday themes already had a history. Most prominent of all was love—scenes of elegant young men and women amusing themselves with games, music, and dance in an often idyllic setting.9

A sixteenth-century copy of a wall painting or panel that was made around 1430 in the circle of Philip the Good shows that such subjects also had a place in painting (fig. 15).10 The jester, the only figure not dressed in white in this painting, would certainly have been present in reality at this sort of court party, but he was also included in the scene to point up the folly of all these loving couples. He retained this function of critical and comical commentator in countless genre works until the end of the sixteenth century. In the background people are hunting, the other occupation that was very popular in medieval art. Strikingly these two subjects—courtly love and the hunt—are the very ones that seemingly lost their appeal. The hunt remained popular on tapestries, but is almost entirely absent from painting in the sixteenth century. And where love was concerned, the focus in both printmaking and painting swung around to the more licentious side.

An important tradition in the depiction of scenes of daily life featured the activities associated with the months and seasons.11 Nowadays we know them chiefly from miniatures in books of hours, but in Italy, for instance, they have also survived as frescos. Perhaps the most famous calendar sheets are those in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry begun by the Limbourg Brothers around 1415. In the representations of the seasons the emphasis is on farming—ploughing, sowing, and harvesting (fig. 16). Entirely in accordance with the medieval class society, the work is done by peasants. When the aristocracy or wealthy bourgeoisie are portrayed, they are engaged in the pursuit of pleasure—hunting, revelry, and games. In the magnificent murals in the Torre dell’Aquila in Trento, which date from around 1400, January is represented by fashionably dressed ladies and gentlemen throwing snowballs.

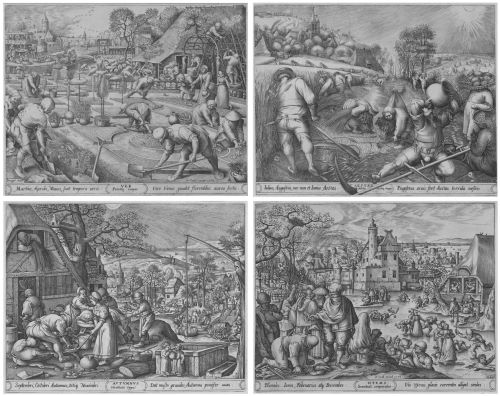

Depictions of the months remained popular for books of hours until well into the sixteenth century, but here again the subject does not appear to have been picked up straight away by printmakers and panel painters after 1500. It was only with Bruegel’s famous months series that the theme was presented in a set of panels (fig. 17). All sorts of figures engaged in everyday occupations also appear in illustrations of the five senses—which first appeared as fully-fledged genre scenes around 1490—and the “children of the planets.”12

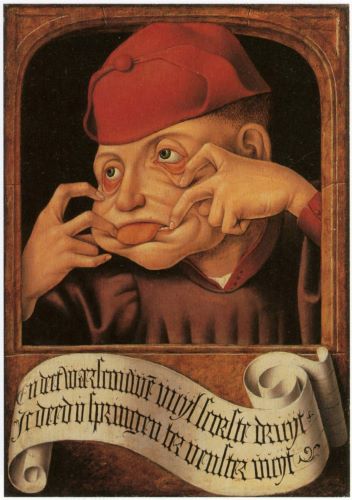

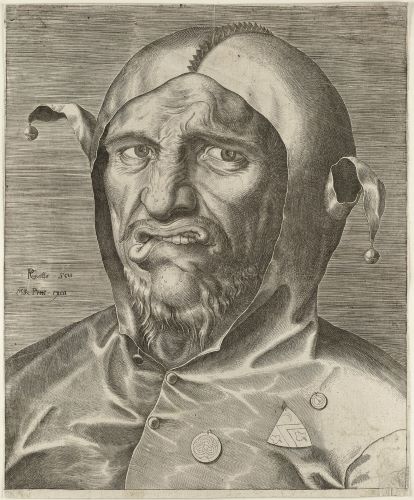

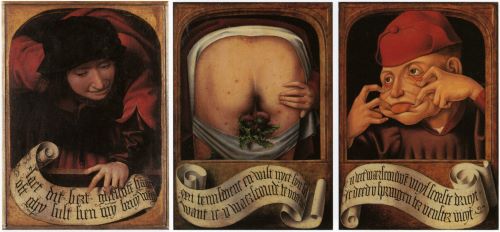

When choosing their subject matter, artists appear to have permitted themselves the greatest license in misericords, the woodcarvings on the underside of hinged seats in medieval choir stalls.13 On the misericords in the Church of St. Peter in Louvain (figs. 18, 19), installed between 1438 and 1442, a woman uses both hands to pull her face into a grimace, sticking out her tongue in the same way as the fool on the satirical diptych by an anonymous Flemish artist (figs. 20, 21), and a jester with a twisted mouth bears a remarkable resemblance to the much later engraving by an artist in Bruegel’s circle (fig. 21).

In St. Salvator’s Cathedral in Bruges, the misericords, which date from roughly the same period, are decorated with all sorts of commonplace subjects, such as a child learning to walk, a couple sitting at table, and a master punishing a pupil, and in the Church of St. James in Liège, various figures have been relieving themselves under the choir stalls since 1400. They are the forerunners of the defecating figures we encounter in countless sixteenth-century paintings and prints. Similar risqué sculpted and carved motifs were already adorning the façades of houses and town halls in the Middle Ages. Metal badges and the margins of illuminated manuscripts were also decorated with such “drolleries.”14 Genre-like scenes are found early in miniature art, particularly as illustrations to narrative works like Boccaccio’s Decameron.

The genre art developing in the sixteenth century did not, though, take its inspiration from profane images alone. The ubiquitous religious paintings must have been another important source. A remarkable aspect of fifteenth-century religious paintings is that the figures they depict usually wear contemporary dress, making it easier for viewers to empathize with the event depicted. Utensils for eating and drinking were also accurately copied from existing objects.15 Around the time of Jan van Eyck, artists started to add genre-like elements to scenes from the life of Christ. In the Budapest copy of Van Eyck’s Christ Carrying the Cross, one of the bystanders is a peasant woman with a basket on her head, evidently on her way to market. This became a favorite subject in the fifteenth century, and one that can still be found around 1560 in Beuckelaer’s art (fig. 22). Another frequently portrayed subject in the fifteenth century are shepherds who watch over their flocks but also sleep, make music, and dance—an angel in the sky is all that tells us that this depicts the annunciation of the Christ Child’s birth.

Certain themes in religious art were ideally suited to everyday tableaux. This applies in particular to the Seven Works of Mercy and the Seven Deadly Sins. Neither is really a connected narrative; they are both examples of behavior, good and bad. This made them ideal for placing in the present day. The Master of Alkmaar set his examples of mercy in a town in North Holland (fig. 23). They could pass for pure genre scenes were it not for the presence of Christ among the townsfolk in every picture and God enthroned in heaven on the central panel as an allusion to the Last Judgment.

At around the same time, an unknown artist painted a Last Judgment with the Seven Works of Mercy on the left and the Seven Deadly Sins on the right (fig. 24). The works of mercy are represented here by examples of different saints. The deadly sins are painted as everyday scenes; here, however, a recurring devil is the spoilsport, breaking the suggestion of reality. This depiction of the deadly sins, in particular, is often cited as an important—sometimes the important—precursor of sixteenth-century genre art.16

Countless facets of the everyday were, as we see, already represented in art. Artists had long been observing and recording humans and their doings. Nonetheless, it was a fundamental step to take daily life as the principal subject of engravings, etchings, and paintings on panel and canvas.

Development

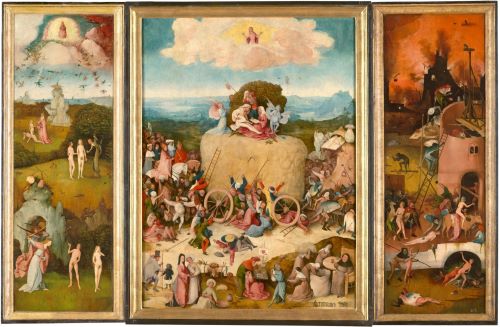

Where painting is concerned, Hieronymus Bosch is regarded as the progenitor of the depiction of everyday life, but the precise importance of this extremely original artist is difficult to estimate. Only two of his surviving paintings, both of which started out as triptychs, are in the nature of genre works. The Haywain is first and foremost an allegory of greed (fig. 25). In truth it has very little in common with an everyday scene: we see the Fall on the left panel and Hell on the right, and the central panel itself would not immediately be read as a genre work. The wagon is drawn by devils, on top of the hay a monster stands playing an instrument while an angel kneels in prayer, and the wagon is followed by the highest spiritual and worldly leaders.

In contrast to the interior, there is not a single detail on the outside of the shutters, with a pedlar at its center, that does not reflect everyday reality (fig. 26).

A similar figure graced the outside of the shutters of Bosch’s other triptych, which at some unknown point was sawn into a number of pieces (figs. 8, 27-29). Inside the left shutter is a ship of fools and on the inside of the right shutter we see the death of an old man.

Sadly, the center panel has not survived, but it is highly likely that this was not a genre-style scene but a biblical subject like the Last Judgment. Complex triptychs such as these were unique in Bosch’s own day and were never imitated. The future lay in individual works with a single subject. Bosch’s importance to further development centered on his decision to paint a very realistic pedlar on the exterior of the shutters and his predilection for painting “outsiders” like fools, quacks, gypsies, blind men, and beggars, as he did in the foreground of the Haywain. In the decades that followed, the dentist and other dubious doctors were to become some of the most popular genre subjects in both printmaking and painting. There are indications that Bosch himself also made genre-like paintings in their own right. Old inventories list canvases with such subjects as stone cutters, magicians, bellows makers, and feasting peasants. Since none of these works has survived we make do with these references and with copies; the question is whether they reflect an original by Bosch and, if so, how faithfully (see figs. 2, 3).

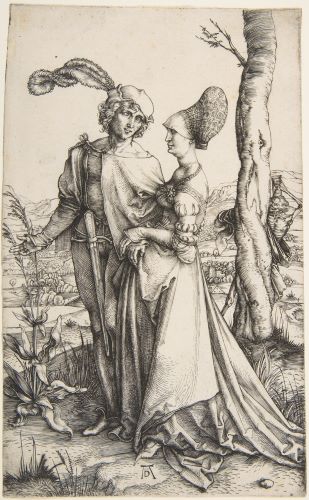

The other two pioneers of genre art, Lucas van Leyden and Quinten Massys, moved in an entirely different direction from Bosch. Of the two, Lucas van Leyden produced the earliest of the known genre works, even though he was a generation younger than Massys. A child prodigy, he began painting and engraving at a very early age. Lucas’s genre paintings are also rare—no more than five panels have survived, all of them small (figs. 7, 30). These pictures represent people playing chess and cards, a fortune-teller, and a betrothal, and they all hint at the tense relationships between men and women. The theme developed from genre prints, where courting couples had numbered among the favorite subjects for more than half a century.

The earliest example is a garden of love made around 1440 by an anonymous Netherlandish engraver known as the Master of the Gardens of Love (fig. 31). While the development of genre painting was a Netherlandish matter, such German artists as Master E.S. also made a significant contribution to printmaking. These early prints, with delicate depictions of elegant figures, have become extremely rare; some are unique, others have survived in only a handful of impressions.

The most attractive love scenes were executed between 1475 and 1485 by the Master of the Housebook, whose drypoint prints are outstanding in their vitality and originality. In his work, we see for the first time an interest in such outsiders as peasants, gypsies, and musicians (fig. 32).

Lucas van Leyden’s genre prints—under twenty of them—derive from this late medieval tradition, but his great exemplar was unquestionably Albrecht Dürer. With his technical perfection, graphic sophistication, and innovative compositions, Dürer had set the tone, around 1500, for future generations (figs. 33, 34). In genre, Lucas surpassed him in diversity. Soldiers, beggars, courting couples, pilgrims, musicians, quacks, and swindlers—he chose rich and varied subjects. The Milkmaid presents a high point in the history of genre prints (see fig. 6).

The majority of Lucas’s genre prints are modestly sized, subtle engravings. Around 1517, however, he also designed a large woodcut of an inn scene that became a model for many later “brothels” (fig. 35).

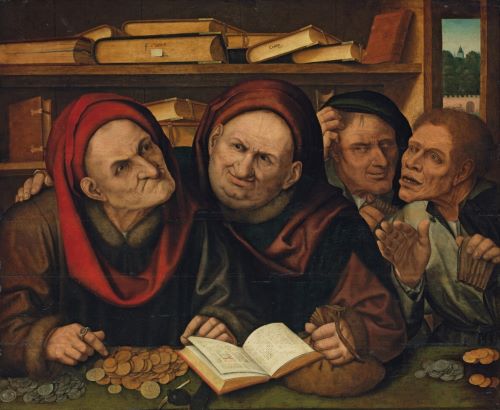

Like Hieronymus Bosch and Lucas van Leyden, Quinten Massys was first and foremost a painter of religious subjects. Although his genre works can be counted on one hand, they were tremendously influential. Massys loved caricature, sometimes following his slightly older Italian contemporary Leonardo da Vinci quite literally. Some of the heads in his The Old Misers, Grotesque Couple, and Unequal Love hark back to drawings by the famous Renaissance master. Massys employed a refined and detailed painting technique entirely in the tradition of fifteenth-century Flemish artists. Not just in technique but also in subject matter Massys sometimes looked back to his illustrious predecessors. His earliest and most influential genre work, The Moneylender and His Wife of 1514 (see fig. 5) was probably based on a portrait by Jan van Eyck. Together with The Old Misers, the original of which has not survived, the painting marks the beginning of a remarkable tradition of paintings in which people are engaged with money (see fig 4). Just a few years later Jan Provoost followed with his Death and the Miser (fig. 36).

But it was the next generation—Quinten’s son Jan and, even more pointedly, Marinus van Reymerswale—who painted traders, shady lawyers, tenants, and tax collectors, elaborating on the work of the great Antwerp master (fig. 37). This tradition was confined to painting; almost no incidence of it survives in printmaking.

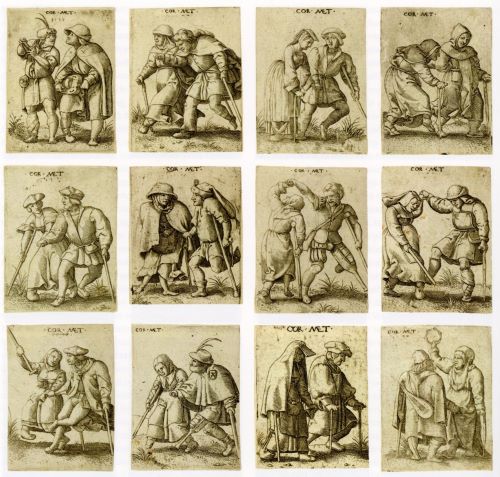

In their genre works, the printmakers of the generation after Lucas concentrated primarily on peasants and brothels. Cornelis Massys, another of Quinten’s sons, did precisely that in a group of very small engravings (fig. 38).

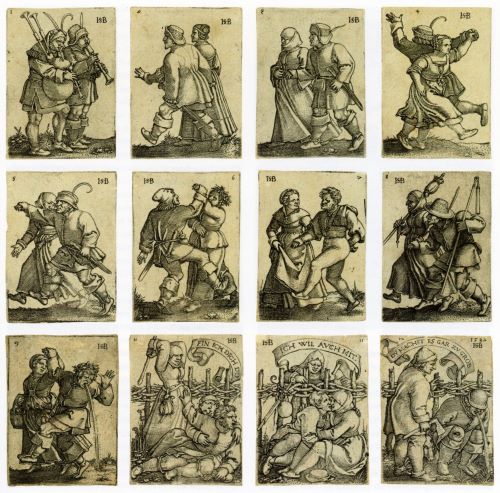

These prints would have been inconceivable without the example of his German contemporary Sebald Beham, the most important of the so-called Little Masters (Kleinmeister), who specialized in tiny prints (fig. 39).

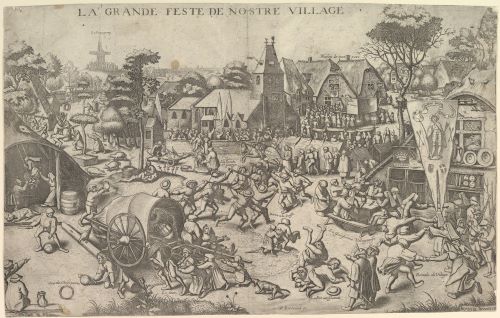

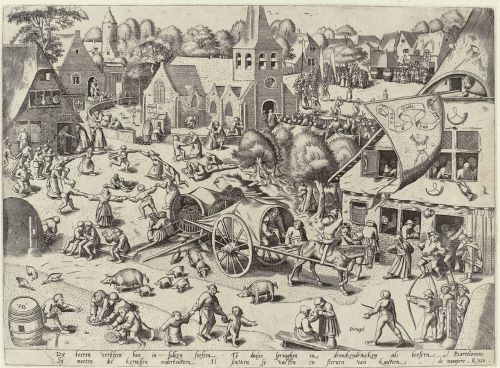

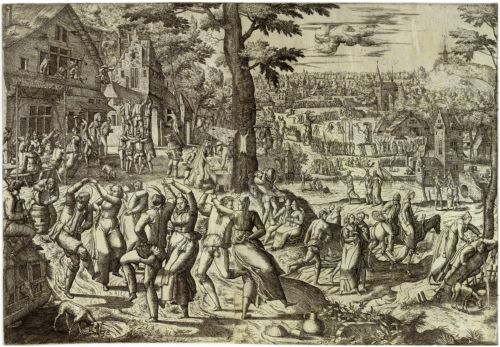

Beham left his mark on the history of genre art, not just with small engravings of dancing peasants but also with some large woodcuts, of which the Large Village Fair of 1535 is the most impressive (fig. 40). This monumental print depicts a view of a village at kermis time, with people eating, drinking, playing, and fighting. It is the earliest work of its kind, anticipating the kermisses of Peeter van der Borcht and Pieter Bruegel. In the small graphic oeuvre of the painter Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, a contemporary of Cornelis Massys, a single print reflects the German tradition. Vermeyen’s principal contribution to the history of genre prints, however, is a group of extraordinary etchings that seem to stand alone in terms of form and content. For the first time, the possibilities of etching were exploited to the full, with fluid, irregular, spontaneous lines.

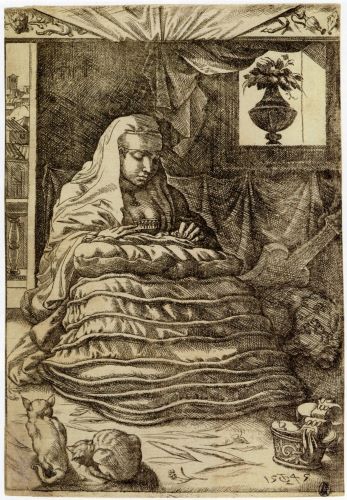

The most interesting are a few prints prompted by Vermeyen’s journey to Spain in 1535. As a counterpoint to a rowdy brothel scene there is the serene Spanish Courtesan, with an intimacy that anticipates seventeenth-century Dutch interiors with women (figs. 41, 42).

The most eminent painter in Antwerp after Quinten Massys’s death in 1531 was Jan Sanders van Hemessen. He positions his figures, usually lifesize and extremely detailed, close to the picture plane, to give viewers a sense of being part of the scene. The heads, tending slightly toward caricature, and the often mannered poses in no way detract from the astounding immediacy of his best works, such as Cutting the Stone, the brothel scenes, and The Tearful Bride (figs. 43, 44).

The dividing line between Van Hemessen’s genre works and religious paintings is sometimes very narrow. At first glance his Prodigal Son differs little from his brothel scenes (see fig. 13). But when we look closely at the background we see tableaux that make it clear a biblical parable is depicted here. Like Lucas van Leyden before him, Van Hemessen was fond of compositions in which the religious story receded into the background and the foreground resembled a genre scene in every respect.

The same partiality can also be found in the work of Van Hemessen’s contemporary, the Brunswick Monogrammist, who likewise lived and worked in Antwerp. Nevertheless, he specialized in scenes with many small figures. In his Ecce Homo and Entry into Jerusalem, Christ can be discerned only with difficulty behind the dozens of figures in the foreground who appear to differ little from Antwerp burghers of the first half of the sixteenth century (fig. 45).

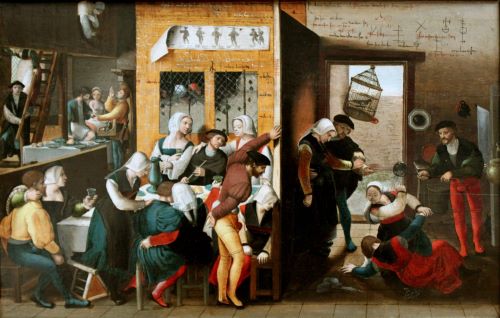

The Monogrammist’s two brothel scenes, which appear almost to be snapshots (figs. 46, 47) are extraordinary. The drink flows, the gestures and embraces are elegant. The figures are tellingly characterized—like the man expectantly following a woman up a ladder—and the paintings are full of details, from chickens on the spit to woodcuts of lansquenets pinned up as decoration and vulgar graffiti chalked on the walls.

The love that most genre painters and printmakers depict is rough and direct. Their works are about brothels or old men fondling young women. The courtly love so popular in the Middle Ages, which we still encounter in works by the Master of the Gardens of Love and the Master of the Housebook, is notable for its absence. Nevertheless a few painters specialized in more elegant scenes of this kind. The Master of the Female Half-Lengths painted countless women writing or making music (see fig. 11). At first sight they appear to be stylish aristocratic ladies, but the ointment jar that features in most of them tells us that they actually depict Mary Magdalene. The master also painted works without a religious connotation; the finest example is Three Women Making Music (see fig. 10).

Ambrosius Benson is the other artist to remain more faithful to the courtly tradition. In the two known genre works by him, we see sumptuously dressed ladies and gentlemen amusing themselves with drink, food, love and dance (fig. 48).

The most important painter of the next generation in Antwerp, Pieter Aertsen, effectively united the scale and monumentality of Van Hemessen with the Brunswick Monogrammist’s bright colors and narrative content. Aertsen’s Peasant Company by the Fire is in fact a massive enlargement of a few details borrowed from the Monogrammist (fig. 49).

Aertsen’s brothel visitors, however, are not lansquenets and burghers but predominantly country folk. He was the first painter to portray peasants on a monumental scale on large panels. In that regard his Peasants’ Feast of 1550 is a milestone (fig. 50). Aertsen was also innovative in his rendition of markets and kitchens. Amidst a profusion of produce he painted lively peasant girls, market women, and kitchen maids. Aertsen worked closely with his nephew Joachim Beuckelaer, who specialized in market and kitchen scenes (see fig. 22).

The monumental depiction of peasants begun by Aertsen was picked up and taken forward by Bruegel. The results were some of the most memorable paintings of peasant festivities, in which technical virtuosity went hand in hand with humor and an astonishing sureness of touch in capturing bearing and movements (fig. 51). Notably, he was not solely interested in fairs and weddings; he also pictured country folk working, breathing new life into the old tradition of images of the months (see fig. 17).

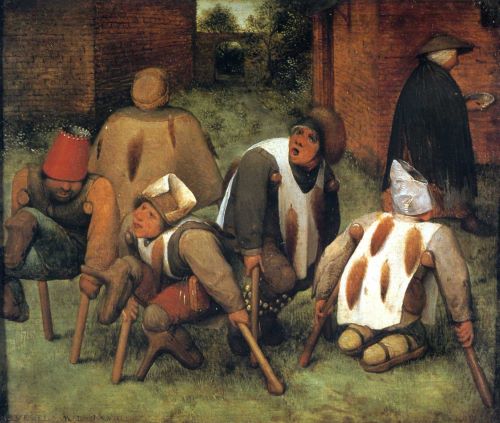

But Bruegel was much more than “Peasant Bruegel,” he was extraordinarily wide-ranging in the subjects he chose. Even in his own day he was seen as a second Bosch—for his images of devils, to be sure, but also for his interpretations of proverbs and his fondness for outsiders like cripples and beggars (figs. 52–54).

Varied as his oeuvre may be, however, it was above all his peasant kermisses and weddings that exerted a huge influence until well into the seventeenth century. These works had already profoundly impressed such artists of his generation as Peeter Baltens, Marten van Cleve, and the slightly younger Hans van Wechelen (figs. 55, 56). Their interpretations of feasting peasants would have been inconceivable without his example.

Prints, which circulated much more widely than paintings, were of fundamental importance in all this. Bruegel had designed prints right from the start of his career. He supplied the drawings for engravings and etchings executed by others, including two kermisses and a scene of skaters on the ice (figs. 57–59).

In the first century of their existence, genre prints were produced in various Netherlandish and German towns and cities, among them Nuremberg, Bruges, and Leiden, but in the second half of the sixteenth century Antwerp acquired a monopoly on innovative prints of everyday scenes. Two publishers in the city, which became the center of printmaking in the North, took the initiative for these prints: Hieronymus Cock, Bruegel’s regular publisher, and Bartolomeus de Mompere, who concentrated primarily on a number of etchers working in Mechelen. They included Peeter van der Borcht, whose striking kermis prints were actually made before Bruegel’s (fig. 60), Frans Hogenberg, and Hans Bol.

After Bruegel’s death in 1569, Cock commissioned Bol to complete his unfinished set of the four seasons (fig. 61), and the artist also contributed in other ways to the flourishing of genre prints.

With Bruegel, genre had become an accepted art form in its own right and one that was an integral part of painting and printmaking. Bruegel himself made roughly as many biblical as genre paintings, but his contemporary Marten van Cleve has left virtually nothing but genre paintings. The popularity of the depiction of everyday life would only increase thereafter.

Boundaries

The history of early genre is chiefly a Netherlandish story, with Antwerp as the undisputed center of activity, alongside pioneering work in ’s-Hertogenbosch and Leiden. Genre works of the highest standard were also created in Brussels, Bruges, Mechelen, and Amsterdam, and even in surprising places like the small town of Reimerswaal in Zeeland. As well, there were German artists who played a crucial role in genre printmaking, particularly in the fifteenth century—when printmaking was still an anonymous job and the precise place where an engraver worked was by no means always certain. The history of printmaking could not be told without Dürer and the same is true of genre prints, to which he made a fundamental contribution, particularly with Peasant Couple Dancing (see fig. 34). Sebald Beham also played a pioneering role in the theme of the peasant celebration. German painting, by contrast, is virtually absent from this story. Everyday scenes are essentially impossible to find. The major exception is the theme of unequal love, which enjoyed unparalleled popularity around 1530 in the oeuvre of Lucas Cranach the Elder (fig. 62) and was also painted by other German artists like Hans Baldung Grien.17

Italian artists likewise did not paint many genre motifs, although some pictures of groups of people making music do exist. It is often hard to say for certain whether they are scenes from everyday life; the border with allegory and portrait is blurred. Not until the end of the sixteenth century, in other words in the period after Bruegel, did Vincenzo Campi and others start to paint genre subjects on a larger scale; the influence of Aertsen and Beuckelaer is evident.18 Genre motifs had been depicted in Italian prints before that time, ranging from the caricatural companies in the spirit of Leonardo to the satirical prints published in Venice with such subjects as the “world turned upside down” and the Land of Cockaigne.19 Compared with the volumes produced in the Low Countries, however, the Italian contribution is modest. The same holds for French printmaking, where we find little in this vein until the end of our period—mainly the popular woodcuts of Rue Montorgueil, where the Paris print trade was concentrated at that time.20

In the exhibition Uncovering Everyday Life, we have confined ourselves to painting and printmaking, the media of the most original genre scenes. Where drawings are concerned, various designs for prints have survived, but they were only a means, not an end in themselves. Drawn genre compositions that were not print designs can be counted on the fingers of one hand, at least in terms of completed compositions and finished sheets. We know of two such drawings by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, Bruegel’s teacher—one of a peasant gambling away his money in a brothel and one of a moneychanger and his wife (fig. 63). There is also a surviving sheet by Bruegel, his enigmatic Beekeepers of around 1568, that did not serve as the model for a print. Figure studies by Bruegel exist outside the scope of this introduction, along with those by other artists. A sketch of a peasant or a herdsman may come across as a genre work, but a motif of this kind could equally well be used to populate a religious or allegorical scene.

Lucas van Leyden must have made a great many such studies in preparation for the dozens of figures that populate his Dance Around the Golden Calf (fig. 64), although not one has survived.21 It is only in the background to this triptych that Lucas makes clear that what we see here is an Old Testament story and not an ordinary festivity where people eat, drink, dance, and make love. The fact that the profane is so prominent in the foreground here, as we often find in Lucas’s work, still does not make it a genre work. The exhibition presents as genre artworks that are varied and diverse in form and content. They reside somewhere between the two extremes of allegory and topography, as the motif of the haywain can clarify. In Bosch’s work, that haywain served as the center of an allegory. Above and below it, admittedly, genre motifs appear, but the whole thing does not for a moment look as if it is a picture of everyday life.

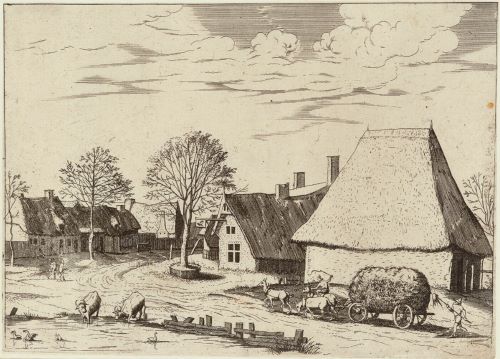

Such an impression is definitely given, though, by Village Street with a Haywain, an etching in a series of village views in the environs of Antwerp which, according to the title page, were drawn “from life” (fig. 65).22 One could arrive no closer to everyday reality than this in Bruegel’s day, although here, too, we certainly have nothing like a snapshot. We see a perfectly ordinary hay-wagon with some peasants, in a virtually deserted village with an inn where nothing happens.

In “real” genre scenes something is always going on. If it is about everyday life, it is a day or a moment when things are just slightly different and routine is interrupted, such as a fair or a wedding, a visit to a tavern or a brothel. The earliest genre works, still in the fifteenth century, reflect primarily the lives of the elite, but here too they depict special moments such as celebrations, games, and the hunt. Peasants were shown making merry and also working, but then mostly at high points in the annual cycle, like harvest in the summer months and slaughtering animals in the autumn. We never see them digging up weeds or mucking out stalls, although jobs like those would have been much more typical of their lives. The different types that are pictured are likewise anything but commonplace—they are pedlars, beggars, cripples, quacks, lansquenets, and other colorful, eye-catching figures. There are few, if any, bakers and builders, but the most glaring absence is that of the ordinary burgher.

The development of genre art from Bosch to Bruegel was anything but a straight line. Some subjects were depicted only once or twice, others enjoyed brief popularity, but then disappeared, and others re-emerged again after a while. Alongside genre in the narrower sense of the word, we also find in this period illustrations of proverbs, of unequal love and, in particular, of the topsy-turvy world, where the wife wore the breeches at the expense of her husband (fig. 66). In these works, the everyday mingled with allegory, satire and morality.

Morality

The author who described with evident delight and admiration the wall decorations in the house of the prelate in Wiesbaden around 1385 (mentioned above), believed that the desires of the flesh—in his view the most heinous sin along with transitory greed and empty vanity—could not have been pictured better than in these scenes of revelers and visitors to public baths. It is clear from representations of the Seven Deadly Sins that he was not the only one who thought this way. Probably around 1510–20 a follower of Bosch painted scenes including peasants fighting, courting couples, and a woman looking in a mirror on his tabletop (fig. 67). The inscriptions by each scene tell us that they represent Ira (wrath), Luxuria (lust), and Superbia (vanity). Very similar scenes were painted lower right in the Last Judgment that was probably executed in Antwerp around 1500 (see fig. 24). This time the deadly sins are explained in Dutch, preceded in each case, to prevent any misunderstandings, by the words “here is.”

The illustrations of the Seven Deadly Sins have been used by art historians as evidence that the same message underlies every similar composition: guzzling peasants stand for Gula (gluttony), a lounging man is Accedia (idleness).23 But is that really the case? The fact that artists felt it necessary to add a gloss to depictions of the Seven Deadly Sins suggests that the scenes did not speak for themselves. For such genre-style images of the deadly sins, no pictorial tradition existed. Painters chose particular scenes that they considered appropriate, but this is not to say that these subjects automatically illustrated a particular deadly sin thereafter. In this period, an allegory was seldom concealed; even the simplest personifications are identified in large letters. Consequently it seems unlikely that we should assume a warning against sinful behaviour behind every picture of brawling peasants, fornicators, or drunks—particularly since the Seven Deadly Sins was only one of the many traditions on which the early genre artists drew for inspiration. We also come across prosperous young people enjoying themselves out of doors with music and love in illustrations of the month of May. There is virtually never a negative connotation in these works; May and love are also unreservedly praised in myriad poems and songs.24 In a poem dating from around 1556, those who criticize young people’s enjoyment are castigated as hypocrites and moaners: “What youth does is in its nature.”25

The popular images of merchants, bankers, and tax collectors—all figures engaged with money—undoubtedly did refer often to greed, but even there we should be careful. The most important triumphal arch at the entry of Prince Philip, son of Charles V, into Antwerp in 1549 was a paean to trade.26 At the 1561 Antwerp Landjuweel—a festival of poets—all the chambers of rhetoric without exception agreed with the proposition that honest merchants were useful and brought prosperity. Trade was considered a divine institution as long as it was carried out with propriety.27 It would therefore seem that Massys’s Moneylender and His Wife (see fig. 5) and Van Reymerswale’s similar paintings were not condemnations of banking and trade. At most they hint that the desire for material possessions should be moderated.

The interpretation of genre works as veiled allegories of the deadly sins is inextricably bound up with the belief that the function of such works was didactic and cautionary. Paintings are seen as mirrors of sin showing how things should not be done. The evil is presented so that viewers distance themselves from it and refrain from taking that path. From this perspective, genre works serve as lessons and painters as moralists wagging their fingers. But would depicting immoral behavior really have been effective as a means of edification? Might this view not be overestimating the didactic powers of the image?

This function of genre works is often postulated in the context of the Praise of Folly, in which social wrongs are censured by praising human folly. Erasmus himself, however, was not impressed by frivolous or licentious images. He criticized the painters and sculptors of his day, for whom there were no limits to the “filth” they depicted. In his Institutio christiani matrimonii, a treatise on marriage dating from 1526, he wrote that “indecent paintings” should be kept out of the home, if only because they could exert a corrupting effect on the morals of the young.28 Erasmus would not have been amused by the diptych, painted around 1520, of the man exposing his bare buttocks (fig. 68). Another Dutch humanist, Alardus Amstelredamus, was equally dismissive of the lascivious paintings that, he said, could be found in Amsterdam interiors in 1538.29 While Alardus, like Erasmus, directed his barbs primarily at pictures containing a great deal of nudity, in other words not solely at genre works, the third humanist to express his views on what was and was not suitable to adorn a wall explicitly mentioned peasant scenes. In 1548, in the commentary to his German translation of Vitruvius’s De architectura, Walter Rivius denounced those who derived pleasure from “the painting of a drunken, foolish peasant who shits and spits behind the fence.”30 Around ten years before, Sebald Beham had produced a print, the last sheet in a series, featuring just such a drunken peasant (see fig. 39). It is quite obvious that, unlike some present-day researchers, Rivius saw nothing instructive in such genre scenes which, to his great displeasure, made many people laugh.

In interpreting the prints and paintings in this exhibition, we have consequently refused to proceed on the assumption that their primary goal was to convey a moral message. The people who looked at the works, for the most part the elite, were perfectly well aware of accepted standards. They did not need paintings and prints to tell them. So what, then, do they tell us? In every work of art it is necessary to search for clues, preferably in the work itself, otherwise in similar compositions or in contemporary literature. The most persuasive are the writings which give an actual description of works of art, not just a commentary on the theme they treat. Captions under prints often do the latter, even though they are physically so close to the images.31 This makes Karel van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck of 1604 by far the most important source, including for the genre art of the previous century. The author was usually well informed about the lives of the most eminent artists who pictured everyday life—and he also knew what he was talking about, for he had himself drawn and painted genre motifs entirely in the tradition of Bruegel and his circle.

Much escapes us in interpreting the images. As they are today, clothes and appearance are the clearest characteristics that enable us to place someone. But our knowledge of the dress of that time, particularly of the lower social classes, is limited. It is almost impossible for us to tell now whether the garments a peasant is wearing are typical or not. Another sad lack is that we know so little about the first buyers of these works; in only a very few cases do we have a name. The function of the works in people’s houses is largely unknown. When we do know something about them, however, it is of immense use. The fact that a number of Bruegel’s peasant celebrations hung in the dining room of a wealthy Antwerp contemporary is of great importance in reading them.32 Sometimes the tenor of particular works proves crystal clear, despite our lack of knowledge; other times, though, it escapes us altogether.

Criticism, Humor, and Reflection

Beggars, partying peasants, ladies of easy virtue, moneygrubbing lawyers, and miserly tax collectors can hardly be taken as a cross-section of sixteenth-century society. Why, then, is it precisely these types that populate the first genre paintings and prints? The works were created in the most important towns and cities of the Low Countries, with Antwerp, then one of the largest conurbations in Western Europe, as the acknowledged center. The wealthy townsfolk are conspicuous by their absence from these works, however, even though they were the people who bought the prints and paintings. In their normal form, they appear only when the subject is love, as in Lucas van Leyden (fig. 69), or to emphasize the difference in conduct between them and the wildly reveling countryfolk, as in Pieter Bruegel and his followers in their depictions of village fairs (see figs. 55, 57).

The most popular figure in genre art was without question the peasant, which essentially meant everyone who lived in the countryside—and that included two-thirds of the population at the time. While they were depicted as hard-working laborers in the scenes representing the months, in prints and paintings we almost always see them celebrating. They have a knife at their hip, always ready to attack their food or another person. They are portrayed as drunk, licentious, and free with their hands. A poem by Lucas d’Heere about a peasant who falls in love with a city miss exemplifies the stereotypical image of the countryman that townsfolk liked to cherish. The peasant is overcome by desire when he sees the object of his passion. He threatens her gentleman friend with a long knife and warns of his aggression: “For when I am angry, I am mighty fierce.” If she will come to the fair in his village, he will prepare a feast for her with a butchered pig, pies, cakes and tarts, and, of course, beer. He will dress in his finest clothes, with a red cap, feathers, a gold ribbon, and tassels, and, in a suggestive conclusion, he lets her know that he has much more to offer, but he will only let her see it when she is there.33

Peasants were also depicted as stupid and gullible: they are robbed of their money and possessions by women and quacks. They are browbeaten at home; their wives wear the trousers and order them to do such women’s work as spinning, and if they do not comply they are given what for.

The peasants are joined in genre prints and paintings by social outcasts like pedlars, beggars, and cripples. Their role is as ambiguous as that of the peasants. On the one hand, they are portrayed as swindlers: they beg not from necessity but because it is an easy way of getting money. Cripples and invalids are pictured, with evident malicious delight, using sticks, crutches, and other aids (see figs. 38, 54). On the other hand, people were expected to treat the weak and the sick with compassion, and feeding them and slaking their thirst were among the Seven Works of Mercy (see fig. 23). They also served as a warning of the fragility of life and of how prosperity can turn to destitution overnight.

Many of the peasants and beggars are given caricatured features—big noses, hairy pustules, and bulging eyes. Exaggerating certain physical characteristics in depicting the executioners and mockers of Christ and the saints derived from a long tradition, but in the sixteenth century, ordinary people were portrayed in the same way. This seems to have started with Quinten Massys, who in his Old Misers pictured two merchants or bankers with contorted grimaces (see fig. 4). Marinus van Reymerswale, who may have been his pupil, took it further, as we see from the countless versions of his Tax Collectors that have survived. Both these painters and Jan Sanders van Hemessen also appear to have had a striking predilection for old-fashioned dress. Van Hemessen, for instance, gave his brothel visitors fifteenth-century headgear (see fig. 12). The clothes created distance, so that the scenes seem to be set in an indeterminate past.

The peasants, beggars, mercenaries, moneylenders, and tax collectors with their bizarre features and old-fashioned dress display characteristics that the citizen was specifically deemed not to have. They thus formed a pattern of how not to behave. But the tone is more often humorous than moralizing. The notion that the peasants did not live up to the standards of the bourgeoisie must have been regarded as very funny. Bossy wives who ordered their weedy husbands around were also much-loved characters in farces. And yet the peasants are not just comical. In the eyes of the bourgeoisie, they were closer to nature and less influenced by the pernicious town. People were well aware that without them there would be nothing to eat. Their freer sexual manners did not conform to bourgeois standards, but they would undoubtedly have given viewers a thrill.

It emerges from Erasmus’s description of paintings depicting Christ in the house of Martha and Mary, in his 1526 treatise on marriage, that what could not or might not be done according to the prevailing standards made people laugh. To his dismay, people thought it was funny if Peter was shown drunk or Martha made Christ look ridiculous with a stealthy gesture. On a panel of this scene by Pieter Aertsen, we do indeed see Peter indulging in drink (fig. 70).34 The painting and Erasmus’s comment illustrate that jokes were made even at the expense of apostles and saints. It is therefore not surprising that artists had no scruples about ridiculing certain respectable people in genre scenes. In Bruegel’s little painting of cripples, for example, one of the beggars is dressed up as a bishop (see fig. 53). The scene was based on actual events typical of Shrove Tuesday, a time when the social hierarchy and norms were turned on their head for a few days, to universal delight.

In their genre works artists liked to use classical techniques to make people laugh. A sixteenth-century treatise on laughter gave as its first example of visually amusing occurrences the unexpected or unintended exposure of genitalia or a backside.36 This is precisely what happens in Bruegel’s skaters before St. George’s Gate in Antwerp (see fig. 59). Another example is the anonymous diptych in which a man points to an inscription advising the viewer not to open the shutters. If the advice is ignored the viewer is faced with a pair of none too salubrious buttocks (see fig. 68). The same treatise declares that the behavior of people in love is by definition funny.37 This is perfectly exemplified in the paintings and prints of unequal love, where the older men and women are rendered as exaggeratedly ugly. And the same applies to Lucas van Leyden’s elegant love scenes, to which he sometimes added a fool to ram the message home (see fig. 30).

Some artists had a special knack for exploiting the possibilities of visual humor; one such was Aertsen, who put a stoneware “pointed nose” jug—a novelty jug with a face—not on the table but on a stool, as if it was an actual person (see fig. 49). The grand master in this regard, however, was Bruegel, who added a witty detail to virtually every work he made, such as the visual iteration in The Harvest between the sheaves of wheat and the peasant bending over beside them with her behind in the air (see fig. 17).38

Much of the humor was based on recognition. The peasants’ liking for drink so abundantly depicted would certainly have been no less among townsfolk. According to a Venetian ambassador, the citizens of Antwerp were in an almost constant state of befuddlement.39 It was an exaggeration, of course, but the fondness for drink was also reported by Van Mander, who called it the Netherlandish disease.40 The battle for domestic supremacy is a recurring theme in proverbs, farces, and anecdotes. It is interesting in this respect to see how foreigners were struck by the degree of freedom and authority women had. The same Venetian ambassador even wrote that all the trade was done by women precisely because their menfolk were always half drunk.41

In 1584–85 Antwerp had 376 proprietors of drinking establishments, including innkeepers, taverners, and landlords. There were inns where you could eat, drink, and sleep, taverns that had no sleeping accommodation but sometimes served meals, wine-houses, beer-houses, gambling dens, and brothels.42 In the late Middle Ages brothels were tolerated in most Western European towns and cities. As well as in such “houses of ill-repute,” prostitution went on in bathhouses (stews) and in the street.43 The candid depiction of sex for sale we see in genre art has to be understood against this background (see figs. 46, 47). In many of the brothel scenes we encounter mercenaries or peasants, the former as notorious drunkards and whoremongers, the second group as rustic simpletons who are swindled and robbed on their visit to the town. In reality these places must also have been visited by other sections of the population; in any event the paintings found their way onto the walls of wealthy citizens who knew what they were seeing.

The preference was for other social classes or burghers pictured as caricatures to function as the people who did not conform to the standards of the town-dweller. At the same time, however, they held up a mirror to that town-dweller. These layers of meaning are nicely expressed in Van Reymerswale’s Lawyer’s Office (see fig. 37). With his broad grin and corpulent build, the lawyer is an exaggerated figure; his client is a poor peasant, counting out his last few coins. The painting alludes to the proverbial avarice of lawyers and the stupidity of peasants who keep pursuing a case even though it costs more than the sum in dispute. The documents in the background, however, relate to an actual case that was taken all the way to the High Court by two prominent citizens of the painter’s hometown.44

Much of this mirroring would not have been done intentionally. We can still see today that stereotyping and confirming standards often unconsciously go hand in hand with humor, recognition, and even admiration. The paintings and prints do not differ all that much in this respect from what we see on television every day, be it scripted reality programs where young people behave badly in foreign holiday resorts, shows where the presenters are at their happiest when the guests burst into tears and get into a fight, or programs where working-class girls are supposedly transformed into ladies.

A Continuing Development

Genre art came to play an increasingly greater role as the sixteenth century progressed. Nevertheless in this period it by no means attained the status that religious art enjoyed. Karel van Mander tells us that Pieter Aertsen, one of the heroes of this exhibition, had pinned his hopes of immortal fame on his large altarpieces.45 It seems not to have occurred to him that in the end it would be his genre scenes that earned him his place in the history of art. Some of the most successful artists, such as Frans Floris, Jan van Scorel, and Maarten van Heemskerck, did not paint a single genre work.46 However, the advance of the depiction of the everyday proved unstoppable.

The rise in genre art is frequently—and certainly rightly—linked to the rise of the bourgeoisie. Most of these artworks were intended for them and it was chiefly their ideas that were reflected in the paintings and prints. Yet the citizenry had already been a very important power base for a hundred years before genre art really took shape. To some extent the ideas depicted, such as ridiculing peasants, can be found earlier among the aristocracy.47 The first mention of a typical peasant scene like The Tearful Bride (see fig. 44) is in the royal collection of Francis I. The little that we know about the people who commissioned work from Hieronymus Bosch suggests that for the most part they were members of the highest ranks of the nobility in the Low Countries.

It was paintings on panels and canvas and prints—the media in which genre art flourished—that were embraced by the bourgeoisie. Engraving and etching had been used for genre-style subjects virtually from the outset. Like book printing, which was invented at around this time, they proved an ideal medium for the up-and-coming middle class. The new techniques, which meant that works were relatively quick and cheap to produce in numbers, lent themselves to the citizens’ demand for images. Paintings on panel and canvas had a longer history. In the course of the fifteenth century, they were increasingly used to decorate the homes of the middle class. Compared with tapestry, favored by the nobility for decorating their palaces and castles, they were much easier to handle and cheaper to produce. In contrast to murals, they had the advantage of being transportable, so that they could be bought and sold. The national and international trade in prints and paintings soared in the Low Countries during the sixteenth century.48

The immense changes in the religious landscape were of great importance to the development of genre art. Although criticism of the Catholic Church was already making itself heard around 1500, its position at that time was still mostly unquestioned. By around 1570 the Reformation had put an end to that. The role of the artist in the service of the church had also come under pressure. A significant proportion of the reformers, Calvin among them, wanted images removed from churches. That they were serious about this was proved by the iconoclasms that took place in Germany and Switzerland in the fifteen-twenties and thirties and in the Low Countries in the sixties. These developments meant that biblical tales and the lives of saints were no longer the obvious subjects for artists that they had once been, although a large market for private devotional art did continue to exist for a long time. This loss of religious commissions must have been one of the main reasons why painters and printmakers began to make landscapes, still lifes, and genre works. The initial impetus had already been given earlier, but all three came to maturity in the period when the Reformation struggle was at its height.49

These religious changes may be the reason that genre art developed in the Low Countries rather than, say, in Italy, where the Reformation never got a foothold. On the other hand, genre did find a place in printmaking in German and Swiss towns and cities, where the Reformation started early, but seldom if ever appeared in painting. This means that the dynamic in the trade itself must have been at least as important. Once artists in the Low Countries like Bosch, Massys and Lucas had taken the first step, it was evident that the next generation would respond. Bruegel specifically positioned himself in Bosch’s footsteps. This was a very deliberate choice at a moment when other artists, such as Frans Floris, were focusing wholly on Italy. The choice of subjects joined style as a feature of the artistic debate. How strong the tradition was, once it had been established, is clear from the fact that the Netherlands would remain the country of genre art throughout the seventeenth century. Most of the subjects that the famous seventeenth-century artists painted had been established in the period between 1500 and 1570. This applies to Gerrit Dou’s quacks, to Adriaen van Ostade and David Teniers’s peasants and equally to Jan Steen’s merrymakers and proverbs. They all elaborate on a tradition that started at the beginning of the sixteenth century when artists realized that, in Dürer’s words, a good artist can display his abilities as well or perhaps even better “in the depiction of a coarse peasant” than many others in more high-flown subjects.50

Appendix

Endnotes

- H. Rupprich, Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass (Berlin, 1956–69), 2:133. “Dan dy künst des molens würt geprawcht jm dinst der kirchen vnd durch daz angetzeigt daz leiden Cristÿ vnd vill andrer guter ebenpild, behelt awch dÿ gestalt der menschen nach jrem absterben.”

- Rupprich, Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass, 1:167, 169. Dürer received the painting from the Antwerp stadssecretaris Adriaen Herbouts. According to Dürer, the small panel represented Lot and his Daughters. This was almost certainly the work that is now at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

- Rupprich, Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass, 1:151 (Massys), 174 (Lucas van Leyden).

- Never before has a single exhibition or a comprehensive publication been dedicated to the development of sixteenth-century genre art. Regarding the origins of the various “genres” in painting during this period, see L. Silver, Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Rise of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market (Philadelphia, 2006). It was not feasible to process the result of the recent book Peiraikos’ Erben: Die Genese der Genremalerei bis 1550, ed. B. U. Münch and J. Müller (Wiesbaden, 2015), which espouses a broad view of the notion of genre.

- See W. Stechow and C. Corner, “The History of the Term Genre,” Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 33, no. 2 (1975–76): 89–94; and B. Gaehtgens, ed., Genremalerei (Berlin, 2002).

- For seventeenth-century albums of genre prints, see E. De Jongh and G. Luijten, Mirror of Everyday Life: Netherlandish Genre Prints 1550–1700, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1997), 21–24. See also P. Parshall, “Art and the Theater of Knowledge: The Origins of Print Collecting in Northern Europe,” Harvard University Art Museum Bulletin 2 (1994): 17–18.

- See the definition by Albert Blankert: “A genre painting is a painting featuring human figures who are all anonymous and intended to be anonymous.” A. Blankert, “What Is Dutch Seventeenth Century Genre Painting? A Definition and Its Limitations,” in Holländische Genremalerei im 17. Jahrhunderts: Symposium Berlin 1984 (Jahrbuch Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Sonderband 4) (Berlin, 1987), 16.

- C. Will, “Henricus de Hassia über das Wiesbadener Badeleben im 14. Jahrhundert,” Annalen des Vereins für Nassauische Alterthumskunde und Geschichtsforschung 13 (1874): 344–49. We are grateful to Isabel Zinman for her translation from the Latin.

- S. Kemperdick and F. Lammertse, The Road to Van Eyck, exh. cat. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2012–13), no. 50.

- Ibid., no.78.

- See Y. Bruijnen and P. Huys-Janssen, De vier jaargetijden in de kunst van de Nederlanden 1500–1750, exh. cat. (‘s-Hertogenbosch: Noordbrabants Museum/Leuven: Stedelijk Museum Vander Kelen-Mertens, 2002–3). Regarding calendar illuminations, see W. Hansen, Kalenderminiaturen der Stundenbücher: Mittelalterliches Leben im Jahreslauf (Munich, 1984).

- Around 1490, the Senses appear for the first time as full-fledged genre scenes, for instance in a French translation of Bartolomeus Anglicus’s De proprietatibus rerum. One of these illuminations, which may have originated in Hainault, representing Smell, was auctioned at Christie’s in London, June 8, 2005 (no. 11). The representations of Touch and Hearing were held by a London art dealer in 1992. We are grateful to Martina Bagnoli of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, who is preparing an exhibition on the Senses in the Middle Ages, scheduled to open in 2017. For “planet children” in the medieval Hausbuch, see J. P. Filedt Kok, et al., Livelier than Life: The Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet or the Housebook Master , ca. 1470–1500, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Rijksprentenkabinet/Rijksmuseum 1985), 221–42.

- For a survey of misericords, see http://www.ru.nl/ckd/databases/stalla

- Regarding façade sculpture, see C. Grössinger, Humour and Folly in Secular and Profane Prints of Northern Europe, 1430–1540 (London/Turnhout, 2002), 1–3; regarding marginalia in manuscripts, see Vlaamse miniaturen 1404–1482, exh. cat. (Brussels: Royal Library of Belgium/Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2011–12), 112–25. Regarding insignia, see http://www.kunera.nl.

- See P. van der Coelen and F. Lammertse, De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven: Van Bosch tot Bruegel, exh. cat. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2015), 30–31; and other contributions in this book on everyday objects featured in genre paintings.

- See Van der Coelen and Lammertse, De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven, 64–66.

- Alison G. Stewart, Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art (New York, 1977). See also P. van der Coelen, et al., Images of Erasmus, exh. cat. (Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2008–9), 220–23.

- F. Porzio, ed., Da Caravaggio a Ceruti: La scena de genere e l’immagine dei pitocchi nella pittura italiana, exh. cat. (Brescia: Museo di Santa Giulia, 1998–99), 281–93.

- G. J. van der Sman, De eeuw van Titiaan: Venetiaanse prenten uit de Renaissance, exh. cat. (Maastricht: Bonnefantenmuseum/Bruges: Groeningemuseum, 2002–3), nos.V.7, V.10.

- The French Renaissance in Prints from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Armand Hammer Museum of Art/New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1994–95), nos. 143, 146–48, 151.

- Regarding this painting, see J. P. Filedt Kok, De ‘Dans om het gouden kalf’ van Lucas van Leyden (Amsterdam, 2008).

- N. M. Orenstein, The New Hollstein Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450–1700: Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Ouderkerk aan den IJssel, 2006), A101; H. Nalis, The New Hollstein Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450–1700: The Van Doetecum Family (Rotterdam, 1998), 4:118–61.

- First suggested in K. Renger, Lockere Gesellschaft: Zur Ikonographie des Verlorenen Sohnes und von Wirtshausszenen in der niederländischen Malerei (Berlin, 1970).

- Exemplary in this regard is the Antwerps Liedboek from 1544; see H. Pleij, Het gevleugelde woord: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1400–1560 (Amsterdam, 2007), 599–610; see also http://www.dbnl.org.tekst/_ant001antw01_01.

- From the Refereinenbundel by Jan de Bruyne, in a modern Dutch transcription in G. Komrij, De Nederlandse poëzie van de 12de tot en met de 16de eeuw in duizend en enige bladzijden (Amsterdam, 1991), 1071; see further K. Ruelens, Refereinen en andere gedichten uit de XVIe eeuw verzameld en afgeschreven door Jan de Bruyne, 3 vols. (Antwerp, 1879–81).

- See J. Van der Stock, Antwerpen verhaal van een metropool, 16de–17de eeuw, exh. cat. (Antwerp: Hessenhuis, 1993), 39.

- K. Bostoen, “Zo eerlijk als goud: de ethiek van de wereldstad,” in Op belofte van profijt, H. Pleij et al. (Amsterdam, 1991), 333–46.

- Erasmus, Spiritualia and Pastoralia, Collected Works of Erasmus 69, edited by J. W. O’Malley and L. A. Perraud (Toronto/Buffalo/London, 1999), 384–85,428–429. See also Van der Coelen et al., Images of Erasmus, 40–41. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3138/9781442680135

- J. F. M. Sterck, Onder Amsterdamsche Humanisten: Hun opkomst en bloei in de 16e eeuwsche stad (Amsterdam: Hilversum, 1934), 49.

- Quoted from Gaehtgens, Genremalerei, 100. See also A. G. Stewart, Before Bruegel: Sebald Beham and the Origins of Peasant Festival Imagery (Burlington, Vt.: Aldershot, 2008), 137, 268–72.

- Regarding this issue, see P. van der Coelen, “Producing Texts for Prints: Artists, Poets, and Publishers,” in The Authority of the Word: Reflecting on Image and Text in Northern Europe, 1400–1700, C. Brusati, K. A. E. Enenkel, and W. S. Melion, eds. (Boston/Leiden, 2012), 75–100

- See C. Goldstein, Pieter Bruegel and the Culture of the Early Modern Dinner Party (Burlington, Vt.: Farnham, 2013), 37–73.

- L. De Heere, Den hof en boomgaerd der poësien, ed. W. Waterschoot (Zwolle, 1969), 76–77.

- See Van der Coelen, Images of Erasmus, 180–81.

- Pleij, Het gevleugelde woord, 289–94

- In Laurent Joubert, Traité du Ris (Paris, 1579); see J. Verberckmoes, Schertsen, schimpen en schateren: Geschiedenis van het lachen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, zestiende en zeventiende eeuw (Nijmegen, 1998), 114.

- Ibid., 135

- Regarding Bruegel’s humor, see M. Sellink, Bruegel: The Complete Paintings, Drawings and Prints (Ghent, 2007), 23–25.

- A.-M. Van Passen, “Antwerpen goed bekeken. Een bloemlezing,” in Antwerpen verhaal van een metropool, 16de–17de eeuw, J. Van der Stock, ed., exh. cat. (Antwerp: Hessenhuis, 1993), 61.

- K. van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck: Waer in voor eerst de leerlustighe iueght den grondt der edel vry schilderconst in verscheyden deelen wort voorghedraghen (Haarlem, 1604), fol. 240r: “Nederlandtsche sieckte van dranckliefdicheyt.”

- Van Passen, “Antwerpen goed bekeken,” 61.

- P. Verhuyck and C. Kisling, Het Mandement van Bacchus: Antwerpse kroegentocht in 1580 (Antwerp/Amsterdam, 1987), 12, 63. See also B. H. D. Hermesdorf, De herberg in de Nederlanden: Een blik in de beschavingsgeschiedenis (Arnhem, 1977).

- L. C. Van de Pol, “Beeld en werkelijkheid van de prostitutie in de zeventiende eeuw,” in Soete minne en helsche boosheit: Seksuele voorstellingen in Nederland, G. Hekma and H. Roodenburg, eds. (Nijmegen, 1988), 109–12; L. C. Van de Pol, Het Amsterdams hoerdom: Prostitutie in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw (Amsterdam, 1996), 151–60. See also H. Pleij, De sneeuwpoppen van 1511: Literatuur en stadscultuur tussen middeleeuwen en moderne tijd (Amsterdam, 1988; repr. 1998), 94–98.

- See Van der Coelen and Lammertse, De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven, 111.

- Van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck, fol. 244v. See also Van der Coelen and Lammertse, De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven, 177.

- Possibly an exception is Van Heemskerck’s panel Bullfight in Antique Arena from 1552 (Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts), featuring in the foreground a number of genre-like scenes, such as a quack and his audience (R. Grosshans, Maerten van Heemskerk: Die Gemälde [Berlin, 1980], no. 78).

- See P. Vandenbroeck, “Verbeeck’s Peasant Weddings: A Study of Iconography and Social Function,” Simiolus 14 (1984): 83–88, 116. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.2307/3780589

- See F. Vermeylen, Painting for the Market: Commercialization of Art in Antwerp’s Golden Age (Turnhout, 2003); J. Van der Stock, Printing Images in Antwerp: The Introduction of Printmaking in a City, Fifteenth Century to 1585 (Rotterdam, 1998).

- See Silver, Peasant Scenes and Landscapes.

- Rupprich, Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass, 3:284: “Aber dorbey ist zw melden, das ein ferstendiger geübter künstner jn grober bewrischer gestalt sein grossen gwalt vnd kunst ertzeigen kann mer jn eim geringen ding dan mencher jn ein grossen werg.” See J. Müller, “Albrecht Dürer’s Peasant Engravings: A Different Laocoön, or the Birth of Aesthetic Subversion in the Spirit of the Reformation,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 3, no.1 (2011):7 HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.5092/JHNA.2011.3.1.2

Bibliography

- Blankert, A. “What Is Dutch Seventeenth Century Genre Painting? A Definition and Its Limitations.” In Holländische Genremalerei im 17. Jahrhunderts: Symposium Berlin 1984 (Jahrbuch Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Sonderband 4), 9–32. Berlin, 1987.

- Bostoen, K. “Zo eerlijk als goud: de ethiek van de wereldstad.” In Op belofte van profijt, by H. Pleij et al., 333–46. Amsterdam, 1991.

- Bruijnen, Y., and P. Huys-Janssen. De vier jaargetijden in de kunst van de Nederlanden 1500–1750. Exh. cat. ‘s-Hertogenbosch: Noordbrabants Museum/Leuven: Stedelijk Museum Vander Kelen-Mertens, 2002–3.

- De Heere, L. Den hof en boomgaerd der poësien. Edited by W. Waterschoot. Zwolle, 1969.

- De Jongh, E., and G. Luijten. Mirror of Everyday Life: Genre Prints in the Netherlands 1550–1700. Exh. cat. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1997.

- Erasmus, D. Spiritualia and Pastoralia. Collected Works of Erasmus 69. Edited by J. W. O’Malley and L. A. Perraud. Toronto/Buffalo/London, 1999. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3138/9781442680135

- Filedt Kok, J. P. De ‘Dans om het gouden kalf’ van Lucas van Leyden. Amsterdam, 2008.

- Filedt Kok, J. P., et al. Livelier than Life: The Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet or the Housebook Master ca. 1470–1500. Exh. cat. Amsterdam: Rijksprentenkabinet/Rijksmuseum 1985.

- The French Renaissance in Prints from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Armand Hammer Museum of Art/New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 1994–95.

- Gaehtgens, B., ed. Genremalerei. Berlin, 2002.

- Goldstein, C. Pieter Bruegel and the Culture of the Early Modern Dinner Party. Burlington, Vt.: Farnham, 2013.

- Grosshans, R. Maerten van Heemskerk: Die Gemälde. Berlin, 1980.

- Grössinger, C. Humour and Folly in Secular and Profane Prints of Northern Europe, 1430–1540. London/Turnhout, 2002.

- Hansen, W. Kalenderminiaturen der Stundenbücher: Mittelalterliches Leben im Jahreslauf. Munich, 1984.

- Hermesdorf, B. H. D. De herberg in de Nederlanden: Een blik in de beschavingsgeschiedenis. Arnhem, 1977.

- Kemperdick, S., and F. Lammertse. The Road to Van Eyck. Exh. cat. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2012–13.

- Komrij, G. De Nederlandse poëzie van de 12de tot en met de 16de eeuw in duizend en enige bladzijden. Amsterdam, 1991.

- Müller, J. “Albrecht Dürer’s Peasant Engravings: A Different Laocoön, or the Birth of Aesthetic Subversion in the Spirit of the Reformation.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 3, no. 1 (2011). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.5092/JHNA.2011.3.1.2

- Münch, B. U., and J. Müller. Peiraikos’ Erben: Die Genese der Genremalerei bis 1550. Wiesbaden, 2015.

- Nalis, H. The New Hollstein Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450–1700: The Van Doetecum Family. 4 vols. Rotterdam, 1998.

- Orenstein, N. M. The New Hollstein Dutch and Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts 1450–1700: Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Ouderkerk aan den IJssel, 2006.

- Parshall, P. “Art and the Theater of Knowledge: The Origins of Print Collecting in Northern Europe.” Harvard University Art Museum Bulletin 2 (1994): 7–36.

- Pleij, H. De sneeuwpoppen van 1511: Literatuur en stadscultuur tussen middeleeuwen en moderne tijd. Amsterdam, 1988; repr. 1998.

- Pleij, H. Het gevleugelde woord: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1400–1560. Amsterdam, 2007.

- Porzio, F., ed. Da Caravaggio a Ceruti: La scena de genere e l’immagine dei pitocchi nella pittura italiana. Exh. cat. Brescia: Museo di Santa Giulia, 1998–99.

- Renger, K. Lockere Gesellschaft: Zur Ikonographie des Verlorenen Sohnes und von Wirtshausszenen in der niederländischen Malerei. Berlin, 1970.

- Ruelens, K. Refereinen en andere gedichten uit de XVIe eeuw verzameld en afgeschreven door Jan de Bruyne. 3 vols. Antwerp, 1879–81.

- Rupprich, H. Dürer, Schriftlicher Nachlass. 3 vols. Berlin 1956–69.

- Sellink, M. Bruegel: The Complete Paintings, Drawings and Prints. Ghent, 2007.

- Silver, L. Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Rise of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market. Philadelphia, 2006.

- Stechow, W., and C. Corner. “The History of the Term Genre.” Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 33, no. 2 (1975–76): 89–94.

- Sterck, J. F. M. Onder Amsterdamsche Humanisten: Hun opkomst en bloei in de 16e eeuwsche stad. Amsterdam: Hilversum, 1934.

- Stewart, A. G. Before Bruegel: Sebald Beham and the Origins of Peasant Festival Imagery, Burlington, VT: Aldershot, 2008.

- Stewart, A. G. Unequal Lovers, A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art. New York, 1977.

- Vandenbroeck, P. “Verbeeck’s Peasant Weddings: A Study of Iconography and Social Function.” Simiolus 14 (1984): 79–124. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.2307/3780589

- Van de Pol, L. C. “Beeld en werkelijkheid van de prostitutie in de zeventiende eeuw.” In Soete minne en helsche boosheit. Seksuele voorstellingen in Nederland, edited by G. Hekma and H. Roodenburg, 109–44. Nijmegen, 1988.

- Van de Pol, L. C. Het Amsterdams hoerdom: Prostitutie in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Amsterdam, 1996.

- Van der Coelen, P. “Producing Texts for Prints: Artists, Poets, and Publishers.”In The Authority of the Word, Reflecting on Image and Text in Northern Europe, 1400–1700, edited by C. Brusati, K. A. E. Enenkel, and W. S. Melion, 75–100. Boston/Leiden, 2012.

- Van der Coelen, P., and F. Lammertse. De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven: Van Bosch tot Bruegel. Exh. cat. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2015.

- Van der Coelen, P., et al. Images of Erasmus. Exh. cat. Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2008–9

- Van der Sman, G. J. De eeuw van Titiaan: Venetiaanse prenten uit de Renaissance. Exh. cat. Maastricht: Bonnefantenmuseum/Bruges: Groeningemuseum, 2002–3.

- Van der Stock, J. Antwerpen verhaal van een metropool, 16de–17de eeuw. Exh. cat., Antwerp: Hessenhuis, 1993.

- Van der Stock, J. Printing Images in Antwerp: The Introduction of Printmaking in a City, Fifteenth Century to 1585. Rotterdam, 1998.

- Van Mander, K. Het Schilder-Boeck: Waer in voor eerst de leerlustighe iueght den grondt der edel vry schilderconst in verscheyden deelen wort voorghedraghen. Haarlem, 1604.

- Van Passen, A.-M. “Antwerpen goed bekeken. Een bloemlezing.” In Antwerpen verhaal van een metropool, 16de–17de eeuw, exh. cat., edited by J. Van der Stock, 59–67. Antwerp: Hessenhuis, 1993.

- Verberckmoes, J. Schertsen, schimpen en schateren: Geschiedenis van het lachen in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden, zestiende en zeventiende eeuw. Nijmegen, 1998.

- Verhuyck, P., and C. Kisling. Het Mandement van Bacchus: Antwerpse kroegentocht in 1580. Antwerp/Amsterdam, 1987.

- Vermeylen, F. Painting for the Market: Commercialization of Art in Antwerp’s Golden Age. Turnhout, 2003.

- Vlaamse miniaturen 1404–1482. Exh. cat. Brussels: Royal Library of Belgium/Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2011–12.

- Will, C. “Henricus de Hassia über das Wiesbadener Badeleben im 14. Jahrhundert.” Annalen des Vereins für Nassauische Alterthumskunde und Geschichtsforschung 13 (1874): 344–49.

Originally published by the Journal of Historians for Netherlandish Art 11:1 (Winter 2019), DOI:10.5092/jhna.2019.11.1.4, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.