The imperial system he designed endured in various forms for centuries.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The transformation of Rome from a fractious republic to a centralized empire was not an abrupt coup, but rather a masterclass in political manipulation—one orchestrated with unmatched brilliance by Gaius Octavius, who would become Augustus. Emerging from the chaos of civil war, Augustus did not seize power in the traditional sense; instead, he constructed a façade of republican continuity while consolidating autocratic control. Through careful image crafting, calculated legal reforms, strategic alliances, and the manipulation of both public perception and institutional tradition, Augustus fundamentally altered Rome’s political landscape while claiming to restore it.

Here I explore the key strategies Augustus employed to manipulate Rome’s institutions, elite classes, and general population, allowing him to establish and sustain his unprecedented role as princeps—first citizen—while laying the foundations of the Roman Empire.

Inheritance and Early Positioning

The path to Augustus’ unprecedented authority began not with conquest but with a legal fiction—adoption. Upon Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, Gaius Octavius, his great-nephew, learned that Caesar had posthumously adopted him as his son and heir in his will. This act was far more than symbolic. In Roman society, adoption, especially among the elite, was a potent legal tool for inheritance and political continuity. Octavian, as he was then known, seized on this new status as Divi Filius—Son of the Deified One—to build immediate legitimacy. Though only nineteen and lacking military experience, Octavian quickly began leveraging his connection to Caesar to curry favor among Caesar’s veterans and allies, effectively situating himself within the Caesarian camp without appearing to be an upstart challenger to established power. His shrewdness lay in combining traditional Roman reverence for familial duty with the potent emotional legacy of Caesar’s assassination, transforming himself from a relative outsider into the visible continuation of Caesar’s political legacy.1

Octavian’s calculated rise involved aligning with and ultimately surpassing Rome’s most powerful figures, including Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) and Marcus Lepidus. Together, they formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 BCE under the Lex Titia, a law that formally gave them near-absolute powers for five years. Unlike Caesar’s accumulation of power through extra-legal methods, this maneuver allowed Octavian to operate under the guise of legality, presenting his actions as protective rather than revolutionary. The Triumvirate’s bloody proscriptions, notably including the execution of Cicero, served Octavian well by eliminating political enemies and enriching his treasury with confiscated wealth. Yet, Octavian managed to distance himself from the worst excesses, allowing Antony to play the more openly ruthless role while he cultivated an image of youthful piety and civic responsibility. This delicate balance allowed him to exploit the system without appearing to undermine it—a recurring theme in his consolidation of power.2

The death of Julius Caesar had created a volatile vacuum, but Octavian displayed remarkable political instincts for someone so young. He positioned himself as both an avenger and a restorer. His early propaganda emphasized his divine affiliation with the newly deified Caesar, a status recognized by the Senate in 42 BCE. At the same time, he displayed deference to republican norms by seeking legal ratification of his titles and powers. This duality—divine heritage and republican modesty—was no accident. It enabled him to appeal to both popular and elite constituencies, uniting disparate factions under a common banner of restored order and vengeance for Caesar’s murder. Octavian was also acutely aware of the importance of perception. Coins issued during this period boldly advertised his status as Caesar’s heir, sometimes featuring Caesar’s image on one side and Octavian’s on the other, visually linking the old regime with the new.3 This manipulation of public imagery was an early sign of how Octavian would use symbolic language to legitimate his future supremacy.

Octavian’s military acumen also played a pivotal role in reinforcing his early positioning. Though initially lacking experience, he was a quick study and shrewd delegate of military tasks. He relied on seasoned commanders like Agrippa while learning the mechanics of leadership through active campaigns. The defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE—engineered as much through strategy as propaganda—marked the final act in his ascendance. Octavian framed the conflict not as a civil war but as a defense of Roman virtue against Eastern decadence and monarchy, embodied by Cleopatra. By portraying Antony as a corrupted Roman enthralled by a foreign queen, Octavian made himself the defender of Roman tradition. This framing allowed him to crush a rival while reinforcing the illusion that he fought not for power but for the Republic.4 The result was the annihilation of his last major opponent and the birth of a new imperial ideology under the guise of republican preservation.

After Actium, Octavian returned to Rome not as a conquering despot but as a savior. In 27 BCE, he symbolically offered to surrender his extraordinary powers to the Senate. This theatrical gesture resulted in the “First Settlement,” wherein the Senate granted him the honorific title Augustus and control over key provinces and military command. The Senate’s acquiescence was as much coerced as it was voluntary, a testament to the political capital Octavian had accrued. Yet, the brilliance of the maneuver lay in how it masked the transition from republic to monarchy behind a veil of continuity. Augustus did not abolish republican institutions; he neutered them. His early positioning as a modest heir, loyal avenger, and restorer of order had laid the perfect foundation for this transformation. In crafting this persona, Augustus ensured that his dominance would not only be accepted but celebrated by a war-weary public and a complicit aristocracy.5

Propaganda and the Politics of Memory

Augustus’ rise to absolute authority was not simply a product of military victory or constitutional manipulation—it was also the result of an unparalleled propaganda campaign that shaped Roman collective memory and culture. Aware that brute force alone could not sustain power, Augustus carefully constructed an image of himself as the restorer of peace, moral order, and traditional Roman values. This campaign began even before the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra and intensified afterward, saturating Roman society with symbols, monuments, literature, and rituals that elevated Augustus above his contemporaries. He presented his rule not as a rupture with the Republican past, but as a glorious culmination of it, returning stability to a fractured state. This transformation of political reality into a palatable and idealized narrative was among Augustus’ most enduring legacies.6

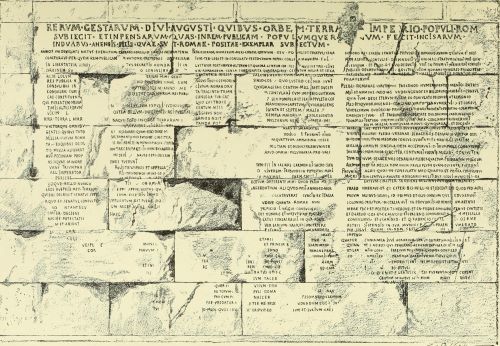

The cornerstone of Augustus’ self-representation was the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“The Deeds of the Divine Augustus”), an autobiographical inscription engraved on bronze pillars in front of his mausoleum and distributed across the empire. In this carefully curated document, Augustus recounts the offices he held, the benefactions he provided, and the victories he won—but all within a rhetorical framework of humility and service to the Republic. Nowhere does he call himself a monarch or dictator; rather, he repeatedly emphasizes that he acted “with the consent of the Senate and the Roman people.”7 This was a masterful act of political memory-making. By omitting the violence of the proscriptions, his conflicts with the Senate, and his calculated sidelining of rivals, Augustus offered Romans a sanitized version of his life that served both as public justification and imperial mythology. The Res Gestae did not just document history; it created it.

Visual propaganda played an equally critical role in shaping Augustus’ public image. Statues of Augustus depicted him as youthful, serene, and idealized—far removed from the gritty reality of civil war and political rivalry. The Prima Porta statue, perhaps the most iconic image of Augustus, presents him in military garb, arm outstretched in a pose of command, with divine imagery such as Cupid and the dolphin at his feet signifying his connection to Venus and his deified father, Julius Caesar.8 Through this statue and others like it, Augustus projected an eternal youthfulness and divine favor, attributes designed to elevate him above mortal politics. The statues not only conveyed military strength but moral virtue and cosmic legitimacy, reinforcing the illusion of Augustus as a quasi-divine figure predestined to lead Rome into a golden age.

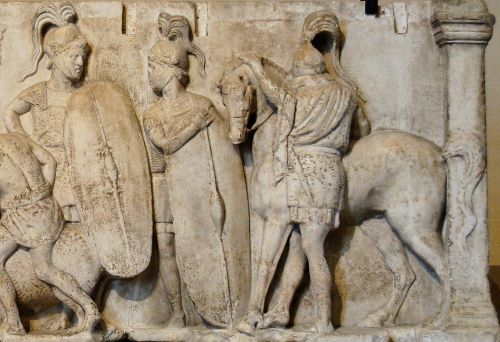

Architecture and public monuments under Augustus also served the politics of memory. The Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), commissioned in 13 BCE, was a masterstroke of symbolic statecraft. Its reliefs celebrate Rome’s return to peace and prosperity, placing Augustus at the center of this providential restoration. Family values, religious observance, and civic harmony are all depicted, reinforcing the regime’s ideology. The very physical presence of the altar in Rome created a space where the Augustan vision of Rome was not just imagined but literally carved into the city’s topography.9 Similarly, the Forum of Augustus, with its statues of Rome’s great men and the Temple of Mars Ultor (“Mars the Avenger”), further situated Augustus within a continuum of Roman greatness while also redefining that tradition through the lens of his own achievements. These spaces instructed Romans how to think about their past—and how to see Augustus as its rightful culmination.

Augustus harnessed literature and the arts to institutionalize his vision of Roman identity. The poets of the so-called “Augustan Age,” particularly Virgil, Horace, and Ovid, were not mere flatterers but active participants in shaping the cultural memory of Augustus’ rule. Virgil’s Aeneid, for instance, tells the tale of Rome’s legendary origins and culminates in the promise of Augustus’ rule, foretold by Jupiter himself. In Book VI, Anchises reveals Augustus as the fulfillment of Rome’s destiny—a ruler who will “bring peace and impose law on the world.”10 Although Virgil’s work contains subtle ambiguities and tensions, its overarching message reinforced Augustus’ central role in Roman salvation. Through literature, public ceremonies, and religious revival, Augustus embedded his image into the very identity of Rome. Memory itself became a tool of governance, shaping not only how Romans viewed their past but how they interpreted their present and future under imperial rule.

Rebranding Autocracy as Republican Restoration

One of Augustus’ most ingenious accomplishments was his ability to consolidate autocratic power while convincing Rome that he was restoring the Republic. After decades of civil war and political upheaval, Romans longed for peace and order, but they remained ideologically attached to the traditions of the Republic. Augustus understood this contradiction and carefully rebranded his authoritarian rule in republican terms. His so-called “First Settlement” of 27 BCE was a masterstroke: he declared the return of power to the Senate and people of Rome (SPQR), even as he retained control over the military and key provinces. In return, the Senate granted him the honorific title “Augustus,” subtly elevating his status without explicitly undermining republican institutions.11 Through a series of calculated gestures, Augustus presented himself as a humble servant of the state while centralizing authority in his own hands. The illusion of republican continuity was crucial to his long-term political success.

Augustus’ manipulation of traditional offices further contributed to the appearance of constitutional normalcy. He rejected perpetual dictatorship and avoided the title of king (rex), both politically toxic in Roman memory, particularly after the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus centuries earlier. Instead, he gathered powers piecemeal: tribunician power (tribunicia potestas), consular imperium, and eventually maius imperium—a superior form of military command valid even in senatorial provinces. These arrangements allowed Augustus to supersede other magistrates without openly dismantling their roles.12 By accumulating overlapping authorities rather than holding overtly tyrannical titles, Augustus ensured that his dominance appeared legally sound and consistent with the republican framework. Even his residence on the Palatine Hill—modest by imperial standards—reinforced the narrative of a “first citizen” (princeps) rather than a monarch.13

A key element of Augustus’ rebranding campaign was his emphasis on moral and cultural restoration. He presented his regime not as a revolutionary break, but as a return to Rome’s ancestral virtues—mos maiorum. Through a comprehensive legislative program known as the leges Iuliae, Augustus enacted laws promoting marriage, discouraging adultery, encouraging childbirth among the elite, and penalizing bachelorhood. These laws, combined with religious reforms and the revival of traditional priesthoods like the Pontifex Maximus, allowed Augustus to position himself as the guardian of Roman morality and tradition.14 This ideological program had the dual effect of legitimizing his rule as a moral necessity and deflecting attention from the unconstitutional nature of his authority. It suggested that Augustus was not imposing a new order but rescuing Rome from decay, restoring a glorious past corrupted by internal strife and moral laxity.

This rebranding extended to the symbolic and religious realms as well. Augustus strategically aligned himself with the pietas and civic virtue of Rome’s mythic founders, particularly Aeneas and Romulus. The poet Virgil—under Augustus’ patronage—crafted the Aeneid as a national epic that positioned Augustus as the inevitable culmination of Rome’s divine destiny. In doing so, Augustus effectively cast his own rule as the fulfillment of a providential plan that stretched back to the Trojan War. Temples were restored or newly built, religious rites reinstated, and traditional festivals celebrated with new vigor, all under Augustus’ direction. By monopolizing the role of restorer, Augustus transformed public religiosity into a form of political consent, embedding his image into the sacred fabric of Roman life.15 Through this synthesis of piety, tradition, and political symbolism, Augustus reframed autocracy as a divine mandate rather than a constitutional subversion.

The Senate itself—once the epicenter of republican deliberation—became a tool in Augustus’ legitimizing strategy. Though still technically operative, it functioned increasingly as a ceremonial body under his guidance. Augustus presided over senatorial meetings, appointed members, and decided its agenda, but he did so while scrupulously observing formalities. He even declined to hold certain offices, such as the dictatorship, when offered, reinforcing his image as a reluctant ruler. This careful theater allowed the Senate to maintain its dignity while ceding real power. Augustus also sponsored public building projects that honored senatorial and republican achievements, such as the Temple of Mars Ultor, which commemorated vengeance for Caesar’s assassination, but within a traditional civic framework.16 By co-opting the Senate and associating himself with its traditions, Augustus neutralized republican resistance and rendered autocracy indistinguishable from restoration.

Manipulating the Military and Elite

Augustus’ consolidation of power would have been impossible without his careful management and manipulation of the Roman military. Having emerged from the chaos of civil war, he understood that the loyalty of the legions was both his greatest asset and his most dangerous liability. In the aftermath of Actium in 31 BCE, Augustus dramatically reduced the number of legions from over fifty to approximately twenty-eight, disbanding tens of thousands of troops and settling them in colonies throughout the empire.17 This not only prevented unrest from an oversized standing army but also rewarded veterans who might otherwise have posed a threat to his authority. Many of these colonies were strategically located to extend Romanization and reinforce imperial loyalty in the provinces. By framing these settlements as generous acts of public service, Augustus gained both political capital and a reputation for magnanimity, all while quietly dismantling potential opposition.

Augustus also implemented a series of reforms that institutionalized his control over the military in ways no previous Roman had attempted. He established a permanent military treasury (aerarium militare), funded initially by his own wealth, to ensure that soldiers received regular pay and retirement benefits—an unprecedented move that made the army directly beholden to him rather than to ambitious generals or the Senate.18 Promotions, honors, and command appointments were also centralized under his authority, ensuring that military careers advanced through imperial favor rather than traditional senatorial patronage. The loyalty this bred was deeply personal: soldiers were bound not to Rome or the Republic but to Augustus himself as imperator. The symbolic consolidation of this loyalty was evident in the oath of allegiance (sacramentum) sworn by soldiers directly to Augustus rather than to the state.19 Through economic dependency, hierarchical restructuring, and ideological reframing, Augustus turned the army into a standing instrument of imperial stability.

Beyond the military, Augustus skillfully co-opted the Roman elite—particularly the senatorial and equestrian classes—into his new political order. Rather than eliminate the traditional aristocracy, he redefined its role and rewards under the Principate. Senators continued to hold magistracies and govern provinces, but only at Augustus’ discretion. Equestrians, once considered a rung below the political elite, were elevated into key administrative and financial posts, particularly in the imperial bureaucracy.20 By broadening opportunities for equestrian advancement, Augustus created a new class of elite loyalists whose power and prestige were tied to imperial patronage. This restructuring diffused traditional senatorial opposition while fostering a new cadre of technocratic allies who owed their careers to Augustus’ favor.

Augustus also manipulated elite culture and expectations by emphasizing moral reform and social hierarchy. The Lex Julia de Maritandis Ordinibus and Lex Papia Poppaea, which imposed penalties on celibacy and childlessness among the elite, were not merely efforts to bolster population growth but to shape elite behavior according to Augustan ideals.21 The laws encouraged a disciplined, family-centered aristocracy aligned with his vision of Roman virtue. In turn, compliance with these laws often became a prerequisite for political advancement. Simultaneously, Augustus lavishly honored cooperative elites through public ceremonies, dedications, and inclusion in priestly colleges—signaling their alignment with the regime while visibly rewarding compliance. He maintained an intricate balance between flattery and control, ensuring that elite families remained powerful but dependent on imperial favor for their status and survival.

Importantly, Augustus maintained a public narrative that disguised this control behind the language of tradition and cooperation. He claimed to have restored the Senate’s authority and emphasized collegiality in state affairs, even as he exercised unchecked dominion. His patronage was always presented as meritocratic rather than coercive, masking the centralization of power beneath the façade of republican norms. This was particularly effective in fostering the illusion of continuity, enabling aristocrats to preserve their dignity and titles while forfeiting true autonomy. Through military reform, elite patronage, and social engineering, Augustus bound the empire’s two most volatile forces—the army and the aristocracy—into a system that depended entirely on the emperor’s person and legacy.22

Dynastic Legitimacy and Religious Manipulation

Establishing a stable and enduring dynasty was among Augustus’ foremost concerns, particularly given the fragility of his own ascent and the precedent of violent succession in the late Republic. Lacking a biological son for much of his reign, Augustus carefully constructed a dynastic image rooted in adoption and symbolic inheritance. He adopted Gaius and Lucius Caesar, the sons of his daughter Julia and Agrippa, and publicly groomed them as successors with elaborate ceremonies, coinage, and civic honors that cast them as heirs to both his power and virtues.23 When both died young, he turned to Tiberius—his stepson—and adopted him as son and heir, further cementing dynastic continuity through another legal fiction. The process highlighted Augustus’ aim to present imperial succession not as personal ambition, but as a natural and moral necessity for the state. This deliberate crafting of a family-centered imperial myth served to normalize hereditary rule, blurring the republican tradition of elected leadership with a monarchical reality cloaked in tradition.

Dynastic propaganda was disseminated broadly through visual culture, especially public monuments, coinage, and statuary. Augustus’ family, the gens Julia, was mythologized through its alleged descent from Aeneas and, by extension, Venus. This divine ancestry was regularly emphasized in literature and art. Statues and reliefs portrayed Augustus surrounded by his heirs, presenting the imperial household not simply as a private family but as a sacred and civic institution. One of the most emblematic examples is the Ara Pacis Augustae, a richly adorned altar dedicated to Peace in 9 BCE, which included processional friezes of the imperial family. The inclusion of children and future heirs linked Augustus’ political stability to his lineage, reinforcing the message that Rome’s peace and prosperity depended on the continuity of his house.24 This visual rhetoric of family and fertility echoed the moral legislation Augustus had enacted, further connecting personal virtue, public stability, and dynastic legitimacy.

Religious manipulation was a crucial mechanism Augustus employed to reinforce his authority and to sacralize the imperial institution. Perhaps most significant was the apotheosis of Julius Caesar, declared a god by senatorial decree in 42 BCE. As Caesar’s adopted son, Augustus became “Divi Filius” (son of the deified one), a title he used regularly in official inscriptions and coinage to bolster his divine favor and authority.25 While not claiming divinity himself during his lifetime—an important concession to Roman distaste for monarchy and deification of the living—he subtly encouraged religious reverence. Temples were built in his honor in the provinces, and the cult of Roma et Augustus was promoted throughout the empire. These cults functioned as unifying imperial religions and served to bind provincial populations to the emperor’s image through ritual and loyalty, creating a common ideological framework across diverse cultures.26

In Rome, Augustus carefully curated his religious persona. He held numerous priesthoods, including pontifex maximus, which he assumed in 12 BCE, giving him formal control over the entire state religion. With this role, he presided over sacrifices, festivals, and the calendar, shaping the ritual life of the Roman people. His reforms to temples and festivals, often framed as restorations of traditional practices, were actually tools to centralize religious authority around his person. By monopolizing religious offices and ceremonies, Augustus positioned himself as the guardian of Roman pietas—a public image that lent moral weight to his rule while reinforcing his political supremacy.27 These religious reforms, though cast as revivals, effectively transformed the Roman religious landscape into an instrument of imperial ideology.

The synergy of dynastic politics and religious symbolism under Augustus was remarkably effective in cementing a system that would endure for centuries. His manipulation of myth, religion, and familial succession allowed him to transcend the label of tyrant or usurper and instead be remembered as a divinely favored restorer of Roman greatness. He left behind not only institutional mechanisms for succession but also a semi-sacred narrative in which each new emperor was not merely a political leader but a continuation of Augustus’ legacy. This blending of divine favor and bloodline authority laid the ideological foundation for the Principate and ensured that subsequent emperors would rule not by mere might, but by the inheritance of a divinely sanctioned order.28 Through dynastic imagery and religious manipulation, Augustus built more than an empire—he established a mythos.

Conclusion: The Quiet Tyranny

Augustus did not wear a crown or wield a scepter as Rome wanted to no part of monarchy, but he ruled with a firm grip nonetheless. His genius lay not merely in seizing power but in making Romans believe they had freely given it. By manipulating law, language, memory, and morality, he transformed himself from an ambitious teenager into Rome’s first emperor, while never officially abandoning the Republic.

The Republic was not destroyed in a day—it was hollowed out slowly, methodically, and subtly. The Senate still met, consuls were still elected, and laws were still passed, but all were puppets in a play choreographed by Augustus. His manipulation was not deception for its own sake, but a sophisticated, pragmatic strategy for creating a stable regime that would last long after his death. Indeed, it did. The imperial system he designed endured in various forms for centuries. His successors may have worn different masks, but the structure—born of his manipulations—remained unmistakably Augustan.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939), 108–110.

- David Shotter, Augustus Caesar (London: Routledge, 2005), 23–26.

- Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990), 36–40.

- Karl Galinsky, Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 70–75.

- Werner Eck, The Age of Augustus (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 50–54.

- Galinsky, Augustus, 95-97.

- Res Gestae Divi Augusti, trans. Frederick W. Shipley in Augustus: The Deeds of the Divine Augustus (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924), sections 1–4.

- Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, 102-106.

- Diane Favro, “The Street Triumphant: The Urban Impact of Roman Triumphs,” in Rome: The Cosmopolis, ed. C. Edwards and G. Woolf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 222–224.

- Virgil, The Aeneid, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Viking, 2006), 6.852–886.

- Eck, The Age of Augustus, 54-56.

- Shotter, Augustus Caesar, 42-45.

- Syme, The Roman Revolution, 313-316.

- Galinsky, Augustus, 118-122.

- Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, 188-191.

- Lily Ross Taylor, “The Divinity of the Roman Emperor,” American Journal of Philology 54, no. 2 (1933): 107–110.

- Eck, The Age of Augustus, 72-74.

- Adrian Goldsworthy, Augustus: First Emperor of Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 272–275.

- Richard Alston, Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt: A Social History (London: Routledge, 1995), 50–52.

- Fergus Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 35–38.

- Susan Treggiari, “Family Life and Marriage in the Julio-Claudian Period,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., vol. 10, ed. Alan K. Bowman et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 874–876.

- Syme, The Roman Revolution, 401-403.

- Eck, The Age of Augustus, 99-102.

- Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, 133-138.

- Galinsky, Augustus, 84-87.

- Duncan Fishwick, “The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire,” Études Préliminaires aux Religions Orientales dans l’Empire Romain 145 (1987): 15–20.

- John Scheid, An Introduction to Roman Religion (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 132–134.

- Syme, The Roman Revolution, 492-496.

Bibliography

- Alston, Richard. Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt: A Social History. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Eck, Werner. The Age of Augustus. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

- Favro, Diane. “The Street Triumphant: The Urban Impact of Roman Triumphs.” In Rome: The Cosmopolis, edited by C. Edwards and G. Woolf, 210–237. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Fishwick, Duncan. The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire. Études Préliminaires aux Religions Orientales dans l’Empire Romain 145. Leiden: Brill, 1987

- Galinsky, Karl. Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian. Augustus: First Emperor of Rome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Millar, Fergus. The Emperor in the Roman World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

- Scheid, John. An Introduction to Roman Religion. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Shipley, Frederick W., trans. Augustus: The Deeds of the Divine Augustus (Res Gestae Divi Augusti). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1924.

- Shotter, David. Augustus Caesar. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939.

- Taylor, Lily Ross. “The Divinity of the Roman Emperor.” American Journal of Philology 54, no. 2 (1933): 107–121.

- Treggiari, Susan. “Family Life and Marriage in the Julio-Claudian Period.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., Vol. 10, edited by Alan K. Bowman et al., 865–889. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Viking, 2006.

- Zanker, Paul. The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.