Compiled in the seventh century BCE for the Library of Ashurbanipal, the NME transformed a diverse body of remedies, rituals, and prognoses into a coherent, serialized whole.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the ruins of Nineveh, once the radiant capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, fragments of clay tablets whisper the story of the world’s earliest known medical “handbook.” Among the thousands of texts recovered from the Library of Ashurbanipal lies a uniquely structured corpus: a therapeutic series that modern scholars now call the NME (NME). Compiled around the seventh century BCE, this collection organized diagnoses, symptoms, and remedies into a coherent, head-to-toe framework, a proto-encyclopedia of human health inscribed in cuneiform.¹ Unlike scattered incantations or ad hoc medical notes, the NME reveals a deliberate project of serialization, systematization, and standardization: medicine arranged as royal knowledge, catalogued as a sequence of treatises, and preserved as part of the Assyrian state’s intellectual arsenal.²

The encyclopedia itself, reconstructed only in recent decades through the joining of hundreds of fragments scattered across museums, is staggering in scope. Modern estimates suggest it comprised roughly fifty tablets with over 10,000 lines of text, arranged into twelve treatises progressing anatomically from scalp to sole.³ Within this framework, one finds prescriptions for eye infections, toothaches, skin ailments, intestinal complaints, and diseases of the limbs, interwoven with incantations and rituals. Such textual layering demonstrates that for Assyrian healers, the physician (asû) and the exorcist (āšipu) worked not in competition but in tandem, their practices unified in pursuit of cure and care.⁴

To situate the NME within the longue durée of medical history is to encounter both continuity and rupture. Continuity lies in its resemblance to later systems (Hippocratic nosology, Galenic compendia, and medieval Latin herbals) in its attempt to map the human body and classify disease. Rupture lies in its particular epistemology: a medicine inseparable from ritual speech, embedded in a world where demons, gods, and symptoms shared explanatory space. Recent philological studies, notably those of Krisztián Simkó and Ulrike Steinert, underscore the sophistication of this enterprise: not a haphazard assemblage but a deliberately serialized canon, the “book” of medicine for the Assyrian king’s library.⁵

What follows examines the Nineveh Medical Encyclopedia (NME) as a literary, medical, and cultural artefact. It explores how the text was compiled and structured, how it integrated therapeutic prescriptions with ritual elements, and how it reflects the broader intellectual ambitions of Ashurbanipal’s library. It further considers its historiographic role: how this reconstruction compels us to reassess long-standing binaries of “magic versus medicine” and to reconsider the roots of systematic medical thought centuries before Hippocrates. In so doing, the NME emerges not merely as an antiquarian curiosity, but as a crucial chapter in the global history of medicine, the earliest known attempt to codify the healing of the body into a comprehensive textual order.

Corpus and Context

The Ashurbanipal Library

The NME cannot be understood apart from the broader intellectual environment of Ashurbanipal’s library. Discovered in the mid-nineteenth century at Kouyunjik (ancient Nineveh) by Austen Henry Layard and his successors, the library contained more than 30,000 inscribed fragments spanning divination, incantations, lexical lists, and historical texts.⁶ Ashurbanipal, who reigned from 668 to 627 BCE, fashioned himself not only as a warrior king but as a patron of scholarship, boasting in his inscriptions that he could read “the cunning tablets of Sumer and the dark Akkadian language.”⁷ The library thus represented both an archive of tradition and a deliberate project of royal knowledge-gathering. Texts were copied from across the empire, edited, and standardized for storage at Nineveh.

Within this intellectual arsenal, medical knowledge held a privileged place. The ability to diagnose, prognosticate, and heal was not simply a matter of practical care but also of political authority. Diseases could threaten royal legitimacy, and their cures were signs of divine favor.⁸ It is therefore unsurprising that medicine (alongside omens, exorcistic rites, and astronomical texts) occupied shelf-space in the king’s curated archive. The NME was part of this same cultural logic: a medical canon fit for the ruler’s library, not just a compendium of recipes for village healers.

Defining the Nineveh Medical Encyclopedia

The designation “NME” is modern, coined by scholars reconstructing the therapeutic texts from Nineveh’s ruins. For decades, tablets with prescriptions and symptom descriptions were treated as isolated pieces. Only through painstaking collation (joining fragments in the British Museum, Iraq Museum, and other collections) did scholars realize that these pieces formed a coherent therapeutic series.⁹

The corpus differs from earlier catalogues such as the Assur Medical Catalogue (AMC). The AMC, produced in Assur some centuries earlier, lists therapeutic works but does not itself present a fully serialized set of treatises.¹⁰ The Nineveh collection, by contrast, demonstrates systematization: approximately twelve treatises arranged anatomically from head to foot, amounting to some fifty tablets.¹¹ This degree of internal coherence, together with its placement in Ashurbanipal’s library, justifies calling it an “encyclopedia.”

In this sense, the NME is not simply a survival of scattered Mesopotamian medicine but an edited, serialized “book,” the closest analogue in the ancient Near East to a medical reference manual. Its head-to-foot organization, explicit colophons, and deliberate standardization all point toward a project of canon-building.¹² It is this editorial coherence that makes the NME a singular witness to ancient Near Eastern healthcare, and not merely another collection of cuneiform prescriptions.

Making a Medical Book in Cuneiform

Serialization and Structure

The NME is remarkable not simply for its content but for its form. Rather than existing as a loose compilation of prescriptions, it was organized into a serialized framework: twelve treatises, each addressing a distinct section of the body, proceeding anatomically from scalp to feet.¹³ Each treatise was distributed across multiple tablets, approximately fifty in total, with clear colophons and catchlines marking sequence and continuity.¹⁴ In this way, the NME represents a textual technology comparable to the later codex: a book-like object in cuneiform, designed to be read in order and to function as a comprehensive manual.

The logic of the arrangement reveals an editorial mind at work. By starting with the head (the seat of sense, consciousness, and vulnerability) and moving downward through eyes, ears, teeth, chest, stomach, limbs, and finally the feet, the NME mirrors not only the physical body but also a conceptual ordering of illness.¹⁵ Diseases were not scattered phenomena but mapped onto a body systematically dissected in text. This topographical method anticipates Hippocratic nosology centuries later, yet remains distinctly Mesopotamian in its interweaving of somatic, environmental, and supernatural causation.

Compilation Mechanics

Reconstructing how such a corpus was produced requires attention to scribal practice. Cuneiform tablets, unlike papyrus rolls, had finite surfaces; long works were therefore distributed across numbered sequences. The Nineveh texts include colophons noting tablet order, scribal provenance, and occasionally the series title, evidence of a deliberate program of standardisation.¹⁶ These paratextual features, together with catchlines (the repetition of a line at the beginning of the next tablet), provided the scaffolding of serialization.

Recent philological analysis has identified editorial strata in the corpus. Krisztián Simkó has shown that the NME bears marks of “serialization,” the weaving together of previously independent therapeutic collections into a continuous work.¹⁷ This process involved aligning formulaic structures, standardizing terminology, and organizing treatments under a consistent head-to-foot scheme. In short, the Nineveh Encyclopedia was not written from scratch but constructed from diverse traditions and unified into a single canon through scribal intervention.

Genres Inside the Encyclopedia

The NME incorporates multiple textual genres, reflecting the pluralistic nature of Mesopotamian healing. Prescriptions (bulṭu) dominate: lists of ingredients, methods of preparation, and instructions for application. These range from topical poultices to ingestible mixtures, often specifying plant-based remedies but also incorporating minerals and animal products.¹⁸ Alongside these, incantations appear, ritual recitations that invoked divine aid or warded off malevolent forces. Finally, short ritual directions describe the performance of ceremonies, often involving purification, offerings, or symbolic acts.

This interlacing of genres illustrates the inseparability of practical medicine and ritual expertise. For the Mesopotamian healer, the patient’s body was a site of both physiological imbalance and spiritual vulnerability. The encyclopedia thus preserves a holistic vision of medicine: a text that was at once pharmacopoeia, ritual handbook, and clinical guide.¹⁹

Sources, Method, and the State of the Text

Archaeology of Fragments

The survival of the NME is as much a story of destruction as of preservation. When Nineveh fell to the Babylonians and Medes in 612 BCE, the palace libraries were burned and toppled into ruin.²⁰ The fire, paradoxically, preserved the clay tablets by hardening them, yet at the cost of shattering them into innumerable fragments. Today, the NME survives only as hundreds of broken pieces, distributed across the British Museum, the Iraq Museum, and other institutions worldwide.²¹

Reconstruction is painstaking. Each fragment must be joined manually or virtually, with joins often requiring decades of comparative study. The British Museum’s “Ashurbanipal Library Project” has recently announced nearly one hundred new joins, many of them in medical texts, which together have clarified the serial order and expanded the known scope of the corpus.²² These discoveries underscore how the NME is still, in many respects, a work-in-progress, a body of text perpetually growing more legible as fragments are reunited.

Digital Philology

The twenty-first century has transformed the methods available to Assyriologists. Projects such as the NME Project (NinMed) and the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus (ORACC) have created digital editions of medical texts, complete with transliterations, translations, and searchable annotations.²³ This infrastructure allows scholars to compare variants, trace recurring formulae, and reconstruct the broader editorial logic of the NME.

One of the most significant outcomes has been the ability to study editorial layers. By comparing ductus (the handwriting of cuneiform signs) and colophon formulae, scholars like Krisztián Simkó have identified different “groups” of tablets that reflect distinct stages of compilation.²⁴ Such analysis reveals that the NME was not a single act of authorship but a layered process of editing, in which older therapeutic traditions were serialized into a new, standardized framework for the royal library.

Limits and Uncertainties

Yet despite the promise of new technologies, the NME remains incomplete. Many tablets are too fragmentary to reconstruct, leaving lacunae in sequences; others survive only in later copies or parallels. Even where transliterations exist, uncertainties in Akkadian vocabulary, especially for plant names and disease terms, caution against overly confident modern diagnoses.²⁵ Scholars increasingly emphasize the necessity of reading the NME on its own cultural terms, resisting the temptation to retrofit symptoms onto modern categories.

Moreover, the dispersal of tablets across institutions poses challenges of access. While the British Museum has made considerable progress in digitization, other fragments remain unpublished or locked in archives. The NME, therefore, is both an ancient text and a modern scholarly project: its very existence as an “encyclopedia” is the product of two millennia of survival, centuries of archaeological recovery, and decades of philological reconstruction.

From Head to Foot: Anatomy as Organizing Principle

The Head-Focused Cluster

The most striking feature of the NME is its head-to-foot organization, a principle that underlies all twelve treatises. The series begins with the head, reflecting both practical and symbolic concerns.²⁶ The head was understood as the seat of thought, sensation, and vulnerability; it is here that ailments most threatened perception and identity. Accordingly, the opening tablets treat a dense array of conditions: headaches, scalp diseases, disorders of the eyes, ears, and nose, as well as dental afflictions.²⁷

The Eye-Disease Treatise, reconstructed in detail by Markham Geller and Strahil Panayotov, exemplifies this approach. Spanning multiple tablets, it lists symptoms ranging from redness and discharge to blindness, followed by therapeutic prescriptions such as salves, poultices, and herbal infusions.²⁸ Each entry combines symptom description with remedy, occasionally prefaced by short diagnostic clauses (“If a man’s eye …”), suggesting a systematic attempt to link clinical observation with treatment.

Progression Through the Body

From the head, the encyclopedia moves downward in an orderly sequence: neck and throat disorders, chest and pulmonary complaints, abdominal and gastrointestinal diseases, then into the limbs and feet.²⁹ This “anatomical descent” was not unique to Nineveh; traces of similar ordering appear in the Assur Medical Catalogue and later in Greek and Roman texts.³⁰ Yet in the NME the scheme is executed with unusual consistency, making it one of the earliest known attempts to impose a linear map of the body on medical writing.

This ordering also carried practical value for the practitioner. A healer consulting the series could move directly to the section most relevant to the patient’s symptoms, whether toothache or stomach pain. The encyclopedia was therefore not a random archive of cures but a reference work, its structure serving the dual purpose of intellectual coherence and clinical usability.

Symptom Clusters and Bodily Geography

Underlying this structure was a conception of the body as a landscape of symptom clusters. Diseases were often defined less by causation than by visible manifestation: swelling, discoloration, fever, or pain in a given region.³¹ The encyclopedia thus teaches us how Mesopotamian physicians “mapped” disease: not abstractly, but by locating pathology in discrete bodily zones.

At the same time, the linear descent from head to foot reflects a cultural metaphor of wholeness. By treating the body in sequence, the NME presented itself as exhaustive, a text that could account for every possible ailment. This claim to totality , medicine arranged as a body, is what justifies calling the corpus an “encyclopedia” in the fullest sense.

Therapy, Ritual, and Prognosis

Therapeutic Modalities

At its core, the NME is a compendium of remedies. Prescriptions (bulṭu) make up the bulk of the text, with detailed instructions on preparation and administration.³² Remedies were often topical (salves, poultices, or washes applied directly to the afflicted area) but they could also be ingested or inhaled.³³ Ingredients include a wide range of plant materials (such as juniper, licorice, or mustard), minerals (bitumen, salt, alum), and animal products.³⁴ Instructions specify quantities, methods of preparation (grinding, boiling, mixing with beer or honey), and application techniques.

The sophistication of these recipes indicates a pharmacological tradition with accumulated empirical knowledge. Certain herbs appear repeatedly for particular conditions: asafoetida for intestinal distress, sesame oil for skin conditions, or juniper resin for eye disorders.³⁵ These recurring patterns suggest that Mesopotamian healers observed efficacy and transmitted that knowledge systematically, even while embedding it in a ritual framework.

Ritual and Incantatory Elements

Yet the Encyclopedia is not purely pharmacological. Rituals and incantations permeate the corpus, often interwoven with prescriptions. An entry may prescribe an herbal mixture and then instruct the healer to recite a protective incantation or perform a symbolic act such as fumigation or water libation.³⁶ The presence of ritual reflects the cosmological worldview of Mesopotamian medicine: disease could be caused not only by physical imbalance but by malevolent spirits, divine displeasure, or sorcery.³⁷

The dual roles of healer (asû) and exorcist (āšipu) thus intersect in the Encyclopedia. The asû administered remedies, while the āšipu performed ritual acts, but their functions were complementary rather than opposed.³⁸ As Francesca Rochberg has noted, Mesopotamian medical texts reveal no rigid dichotomy between “science” and “magic”; instead, both modes of healing were seen as necessary responses to affliction.³⁹

Prognosis and Clinical Reasoning

Alongside therapy and ritual, prognostic statements appear sporadically in the text. These often take the form of conditional clauses: “If a man’s eye is red and oozes pus … it is difficult to cure.”⁴⁰ Such notes do not always provide certainty but offer a heuristic framework, distinguishing between treatable conditions and those deemed fatal or incurable. Prognosis here functions as both medical reasoning and cultural reassurance: a way for the healer to manage expectations, allocate resources, and reinforce authority.

What emerges is a tripartite system of healing: practical remedies to address symptoms, ritual acts to neutralize spiritual threats, and prognostic judgments to orient treatment outcomes. Taken together, these reveal a sophisticated clinical mindset: Mesopotamian physicians did not merely apply recipes but also classified diseases, weighed their severity, and adjusted responses accordingly.

Standardization and Editorial Program

Toward a Structured Canon

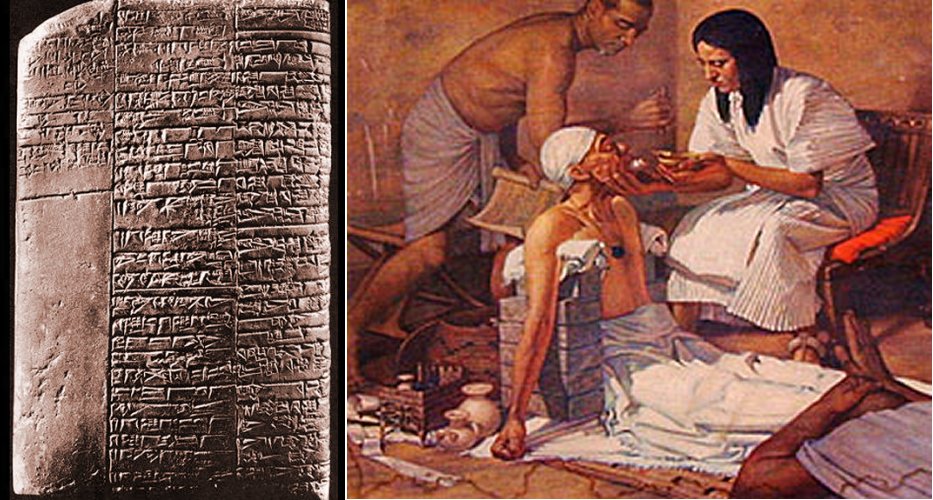

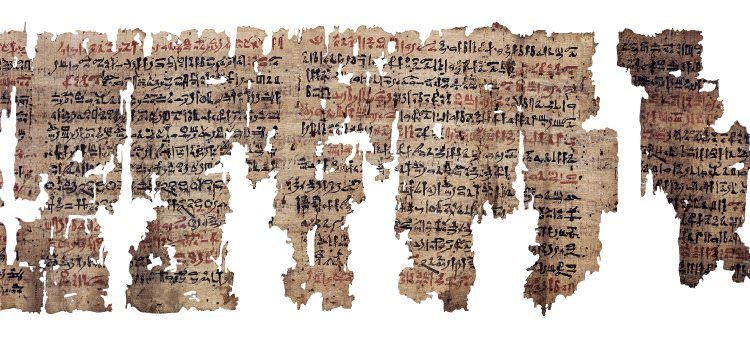

History begins at Sumer; Right: Treatment of a patient.

The defining feature of the NME is its degree of standardization. Unlike earlier therapeutic texts, which often circulated as local collections of remedies or incantations, the NME exhibits deliberate uniformity in structure, terminology, and layout.⁴¹ The tablets follow a consistent head-to-foot order, use similar formulas to introduce prescriptions, and employ colophons to indicate sequence and scribal responsibility.⁴² This level of internal coherence reflects a conscious editorial program rather than mere accident of preservation.

What “standardized, structured, systematized” means in practice can be seen in the series’ treatment of bodily regions. Each treatise begins with a diagnostic formula (“If a man’s head …”), proceeds with a sequence of prescriptions, and frequently concludes with ritual instructions.⁴³ The repetition of this framework across the twelve treatises establishes the NME as a self-consciously ordered corpus, not simply a warehouse of medical lore, but a book designed for reference and authoritative transmission.

Scribal Editing and Serialization

Philological evidence suggests that the encyclopedia was compiled by merging older therapeutic traditions into a newly serialized format. Recent analysis of ductus (sign forms) and colophon patterns shows that different scribal “hands” and editorial layers contributed to the corpus.⁴⁴ Some tablets preserve older, less standardized remedies; others reflect more uniform language and structure, indicating later editing.

Krisztián Simkó has argued that this process of “serialization” was a deliberate act of canon-building, weaving together independent clusters of remedies into a unified encyclopedia.⁴⁵ The inclusion of catchlines linking one tablet to the next, as well as the systematic numbering of tablets within a treatise, demonstrates the extent of this effort. Such editorial intervention transformed fragmentary traditions into a cohesive series, a hallmark of Assyrian scholarly culture during Ashurbanipal’s reign.

Royal Library Agenda

The production of the NME must also be read in the political and cultural context of Ashurbanipal’s library. The king’s project of gathering, copying, and preserving texts from across Mesopotamia was itself an exercise in imperial control over knowledge.⁴⁶ Medicine, like divination and astronomy, was drawn into this centralizing enterprise. By serializing and standardizing the therapeutic corpus, scribes created not just a reference tool for healers, but a monument of royal erudition.

The encyclopedia thus embodies both scholarly ambition and political ideology. It presents a model of medical knowledge as orderly, comprehensive, and universal, fitting for a king who styled himself the custodian of all wisdom. In this sense, the NME is as much a cultural artefact of empire as it is a medical text.

Comparative Frames: AMC, SA.GIG, and Beyond

The Assur Medical Catalogue (AMC)

The most direct comparative source for the NME is the Assur Medical Catalogue, discovered at the Assyrian city of Assur and dated to the early first millennium BCE.⁴⁷ Unlike the NME, the AMC is not itself a therapeutic series but a catalogue of medical works, listing tablets and series titles with brief descriptions.⁴⁸ In many ways, it functions as a librarian’s index: a guide to available treatises rather than a codified handbook.

Yet the AMC provides critical insight into how Mesopotamian scholars conceptualized medical knowledge prior to Nineveh. It reveals an awareness of genre (distinguishing therapeutic, ritual, and diagnostic texts) and it demonstrates that efforts to order medical knowledge predated the NME.⁴⁹ When placed side by side, the AMC and NME illustrate a trajectory: from cataloguing disparate traditions to serializing them into an encyclopedia. The AMC is a map, the NME the library made flesh.

SA.GIG and the Diagnostic Tradition

The diagnostic handbook known as SA.GIG (“Symptoms”) provides another important comparator. Dating from the Old Babylonian through Neo-Assyrian periods, SA.GIG is a massive compendium of diagnostic omens, listing symptoms in formulaic “if … then” clauses with corresponding prognoses.⁵⁰ While it overlaps with the NME in format, conditional clauses introducing medical cases, its orientation is different. SA.GIG is primarily diagnostic and prognostic, focusing on what an illness portends, whether death, recovery, or divine displeasure. The NME, by contrast, is therapeutic: it moves from symptoms directly into prescriptions.⁵¹

Together, SA.GIG and the NME demonstrate a division of scholarly labor. The former represents the diagnostic branch of medicine, tied closely to omen literature and divinatory practice; the latter embodies therapeutic knowledge, emphasizing treatment and remedy. Their coexistence in Ashurbanipal’s library reflects a holistic vision of medicine: not merely identifying disease but managing it through pharmacology and ritual.

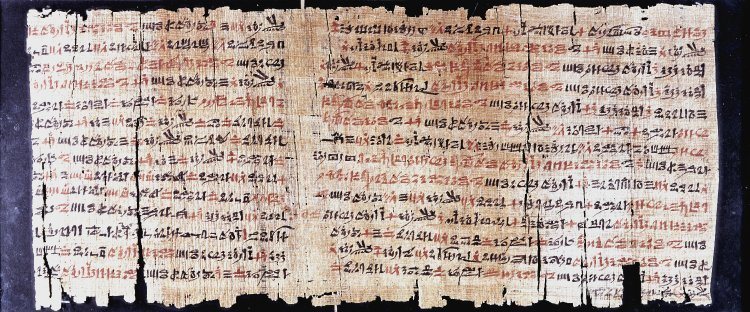

Position in the Longue Durée

The NME also invites comparison with traditions beyond Mesopotamia. In Egypt, medical papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) likewise compile remedies arranged partly by body region, though less systematically.⁵² In Greece, Hippocratic treatises of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE reveal the first attempts at nosological classification, but these works lack the encyclopedic head-to-foot order seen in Nineveh. Later Roman authors such as Celsus (De Medicina) and Galen produced vast medical corpora that echo the ambition, if not the format, of the Assyrian work.

What distinguishes the NME in this comparative frame is its scale and editorial coherence. It is the earliest surviving attempt to render the body as a continuous text, with remedies aligned to an anatomical sequence. In this respect, it stands as a forerunner not only to Greco-Roman medicine but also to the medieval Latin and Arabic encyclopedias that sought to gather the totality of medical knowledge into ordered reference works.

Case Study: The Eye-Disease Treatise

Philology to Clinic

Among the most fully reconstructed portions of the NME is the Eye-Disease Treatise, edited and published in detail by Markham Geller and Strahil Panayotov.⁵³ Surviving in multiple tablets, this treatise begins with symptom descriptions for ocular conditions and proceeds through sequences of remedies. Its structure exemplifies the encyclopedic method: each entry follows a formulaic pattern (“If a man’s eye …”) followed by the symptom, and then one or more therapeutic prescriptions.⁵⁴

The range of symptoms covered is striking: redness, swelling, discharge, blurred vision, ocular pain, and even sudden blindness.⁵⁵ Some descriptions are concise, others elaborate, suggesting a graded severity or a hierarchy of diagnostic clarity. What links them is the consistent movement from observation to remedy, demonstrating an embryonic clinical reasoning. The healer records what is seen and prescribes what is to be done.

Remedies and Procedures

The remedies prescribed for eye disease illustrate the sophistication of Mesopotamian pharmacology. Many are topical applications: salves made of sesame oil, juniper resin, and plant extracts; poultices applied to the eyelid; or washes prepared with beer, milk, or honey.⁵⁶ Some instructions are precise, “grind finely and apply with a bronze needle,” while others are more general, leaving the healer room for practical adaptation.

In some cases, ritual acts accompany the therapy: fumigation with aromatic resins, recitation of protective incantations, or symbolic gestures of purification.⁵⁷ Here again, the roles of asû and āšipu converge, binding together material remedy and spiritual protection. The sick eye is treated as a site of both physical and supernatural vulnerability.

Prognosis and Clinical Limits

Notably, the treatise also includes prognostic clauses. Certain symptoms are flagged as “difficult to cure” or “not curable,” reflecting an awareness of therapeutic limits.⁵⁸ While these judgments cannot be mapped directly onto modern ophthalmology, they reveal a clinical pragmatism: healers distinguished between treatable infections (likely conjunctivitis or styes) and conditions such as blindness where interventions were futile.

Such statements show that Mesopotamian physicians did not assume omnipotence. Instead, they developed a taxonomy of outcomes, balancing optimism with caution. Prognosis thus served not only as medical reasoning but also as a social function: it prepared patients and patrons for the range of possible results, legitimizing the healer’s role even when cures were not forthcoming.

Methodological Caution

Modern scholars stress the limits of retrospective diagnosis. Terms like “red eye” or “oozing” may appear transparent, but mapping them onto modern categories such as conjunctivitis or trachoma risks anachronism.⁵⁹ Akkadian vocabulary for disease is culturally embedded, shaped by Mesopotamian categories of perception and causation. The Eye-Disease Treatise is thus best read as a system in its own right, an organized attempt to understand ocular illness within its own cultural and therapeutic logic.

Nevertheless, the parallels to modern ophthalmology are striking. The repeated use of honey, sesame oil, and resins, all of which have antimicrobial or soothing properties, suggests that empirical observation informed many prescriptions. The Encyclopedia, therefore, stands as both a historical artefact of Mesopotamian cosmology and a witness to a pragmatic, trial-and-error medicine that resonates across time.

Royal Knowledge and Social Medicine

Medicine Fit for a King

The NME must be understood within the intellectual and political milieu of Ashurbanipal’s library. Ashurbanipal, unlike most rulers of the ancient Near East, portrayed himself as a scholar-king, claiming mastery over the “tablets from before the flood” and boasting of his ability to read Sumerian and Akkadian alike.⁶⁰ His collection of texts was not simply antiquarian; it was a declaration of dominion over the totality of Mesopotamian knowledge.

In this framework, medicine assumed a dual significance. On one level, the Encyclopedia provided practical remedies for court physicians treating royal bodies. Illness in the palace could threaten dynastic continuity and was therefore a matter of state security.⁶¹ On another level, the very act of collecting, standardizing, and inscribing medical knowledge projected an image of power: the king who controls healing also controls the well-being of his people.⁶² The NME thus functioned both as a clinical tool and as a political monument, a text whose orderliness mirrored the king’s authority.

Practitioners and Patients

While the NME was preserved in the royal library, its roots lay in the practices of Mesopotamian healers across society. The division between the asû (physician) and the āšipu (exorcist) illustrates the multiplicity of roles in ancient healthcare.⁶³ The asû prepared remedies, drew on materia medica, and dealt directly with symptoms, while the āšipu employed ritual, incantation, and divination to address the supernatural dimension of illness. In practice, these roles often overlapped, and both are reflected in the Encyclopedia’s texts.

The patients envisioned in these texts range from elites to ordinary people. Prescriptions occasionally assume access to exotic ingredients, suggesting courtly contexts, but others list materials easily gathered from local environments.⁶⁴ The NME therefore seems to encode a spectrum of healing traditions, adapted for the needs of both palace and populace. Its placement in Ashurbanipal’s library ensured its preservation, but its contents testify to a living, socially embedded medical practice.

Knowledge as Social Power

The Encyclopedia also reflects the broader Mesopotamian conception of knowledge (nēmequ) as a divine gift and a form of authority. To inscribe remedies onto clay was to stabilize them as part of the cultural archive, no longer dependent solely on oral transmission or local expertise.⁶⁵ In this sense, the NME was not just a medical reference but an act of canonization, elevating certain remedies and rituals to the status of authoritative knowledge.

This process had social consequences. By embedding healing knowledge in the royal library, the state asserted control over its transmission, ensuring that medicine (like divination, astronomy, and law) became part of the apparatus of empire. The Encyclopedia, then, was not only a book about treating the sick; it was a book about ordering the world, enshrining health as part of the king’s domain.

Ingredients, Pharmacopoeia, and Environment

Toward an Index of Materia Medica

The NME is a treasure trove for reconstructing the pharmacopoeia of ancient Mesopotamia. Across its twelve treatises, healers catalogued hundreds of substances, primarily plants but also minerals, animal products, and manufactured materials.⁶⁶ Commonly listed items include sesame oil, honey, beer, milk, resins such as juniper and pine, and aromatic plants like dill and coriander.⁶⁷ These were often combined into complex recipes, with instructions for grinding, boiling, or mixing into pastes and drinks.

Recent philological work has begun to catalogue these substances systematically, tracing their recurrence across tablets and comparing them with other medical corpora such as the AMC and the Ebers Papyrus.⁶⁸ Patterns emerge: sesame oil appears as a carrier in skin and eye treatments, honey as an antiseptic and soothing agent, and beer or wine as solvents for ingestion. Such regularity suggests an empirical awareness of their therapeutic properties, even if framed within a ritualized worldview.

Trade and Ecology

The pharmacopoeia of the Encyclopedia also provides a window into the environmental and economic networks of Mesopotamia. Many ingredients were locally available — barley, dates, sesame, onions, products of the fertile alluvial plains. Others, however, point to long-distance trade: cedar oil from Lebanon, resins from Arabia, and minerals imported from Iran or Anatolia.⁶⁹ The presence of these items underscores the interconnectedness of Mesopotamian medicine with broader imperial supply chains.

This global dimension reveals the Encyclopedia as not only a medical text but also a document of empire. Access to exotic ingredients reflected the Assyrian state’s reach and resources, particularly in the royal court. Remedies demanding rare imports may have been more aspirational than practical for ordinary healers, but their inclusion demonstrates how imperial authority and cosmopolitan exchange shaped the contours of Mesopotamian pharmacology.

Recipes as Scientific Knowledge

The recipes of the NME, while couched in ritual formulae, exhibit features of proto-scientific reasoning. Substances are not listed randomly but paired and repeated in predictable contexts: antiseptic agents in infections, emollients for skin conditions, laxatives for digestive issues.⁷⁰ These patterns suggest that healers recognized functional categories of treatment, even if not articulated in theoretical terms.

At the same time, the text reflects the Mesopotamian understanding of medicine as inseparable from cosmology. Ingredients had not only material properties but also symbolic associations: cedar as purifying, honey as life-giving, water as sacred.⁷¹ The Encyclopedia thus captures a dual register: pragmatic trial-and-error medicine on one hand, and symbolic resonance on the other. This interplay is precisely what makes the text so valuable for historians of science: it preserves both empirical practice and cultural meaning.

Historiography and Reassessment

From Fragments to Encyclopedia

For much of the twentieth century, Mesopotamian medicine was viewed through the lens of scattered prescriptions and isolated ritual texts. Scholars tended to read these as pragmatic but unsystematic, a kind of “folk medicine” lacking the coherence of later Greek traditions.⁷² The rediscovery and reconstruction of the NME has decisively altered this picture. What once appeared as fragmented lore now emerges as a deliberately ordered corpus, serialized into a head-to-foot arrangement that rivals Hippocratic systematisation.⁷³

The very label “encyclopedia” reflects this historiographic shift. Where earlier generations saw a patchwork, current scholarship, aided by nearly one hundred new joins in the British Museum project, demonstrates the existence of a structured series of approximately fifty tablets.⁷⁴ The NME thus forces us to reassess the sophistication of Mesopotamian medicine: not a pre-scientific miscellany, but a consciously edited canon.

Rethinking Magic and Medicine

One of the most important consequences of the NME’s reconstruction is the collapse of the once-dominant “magic versus medicine” dichotomy. Older scholarship tended to divide Mesopotamian healing into “rational” pharmacology on the one hand and “irrational” ritual incantations on the other.⁷⁵ Yet the Encyclopedia reveals these as inseparable modes of care. Prescriptions and incantations appear side by side, woven into a single therapeutic framework. As Ulrike Steinert and others have emphasized, this integration was not a contradiction but a cultural necessity: healing addressed both the material and spiritual dimensions of illness.⁷⁶

This recognition has reshaped comparative historiography as well. By acknowledging that Mesopotamian medicine was at once empirical and ritualized, scholars now approach Greek and Egyptian traditions with greater nuance, resisting the temptation to impose modern categories of “science” onto the past.

Canon-Building and Knowledge Systems

The NME also invites historians to reconsider how knowledge was produced and canonized in the ancient world. Its serialization reflects not only medical practice but also the intellectual politics of Ashurbanipal’s library.⁷⁷ The act of ordering, editing, and inscribing medical texts into a royal archive transformed them into authoritative knowledge, an imperial canon of healing. This process mirrors similar acts of systematization in other fields, such as divination (Enūma Anu Enlil) and lexical lists.

Recent work by Krisztián Simkó has underscored this point: the Encyclopedia is a constructed text, stitched together from earlier collections into a coherent series.⁷⁸ Its existence therefore compels us to view Mesopotamian medicine not as the residue of tradition but as the product of conscious editorial choices.

A New Place in Global Medical History

Finally, the NME reshapes the longue durée of medical historiography. It demonstrates that systematic medical writing predates Hippocratic texts by at least two centuries.⁷⁹ Its head-to-foot ordering anticipates later Greco-Roman and medieval encyclopedias, while its integration of therapy, ritual, and prognosis challenges assumptions about the linear progression from “magical” to “rational” medicine.

Far from being a peripheral curiosity, the NME emerges as a central chapter in the history of medicine. It compels us to reconsider the genealogy of medical knowledge, situating Mesopotamia not as a prelude to Greece but as a foundational contributor to the very idea of a medical canon.

Conclusion

The NME stands as one of the most remarkable intellectual achievements of the ancient Near East. Compiled in the seventh century BCE for the Library of Ashurbanipal, it transformed a diverse body of remedies, rituals, and prognoses into a coherent, serialized whole. With its twelve treatises arranged from head to foot, its consistent use of colophons and catchlines, and its integration of empirical prescriptions with ritual incantations, the Encyclopedia represents nothing less than a medical “book” in cuneiform, the earliest known attempt to render the body as a continuous textual order.⁸⁰

The Encyclopedia’s significance lies in three dimensions. First, it is a clinical artefact: a repository of thousands of prescriptions, many of which reveal empirical insight into the use of herbs, oils, and minerals.⁸¹ Its pharmacological sophistication, combined with pragmatic prognostic notes, demonstrates that Mesopotamian healers balanced observation with ritual in a manner both culturally embedded and strikingly pragmatic.

Second, it is an editorial artefact: the product of deliberate serialization and canonisation.⁸² By weaving together older therapeutic traditions into a structured series, scribes created a new genre of medical literature, one that aligned healing knowledge with the broader intellectual and political aims of the Assyrian state. The NME thus exemplifies how knowledge was not only preserved but also actively shaped, ordered, and standardized in service of empire.

Third, it is a historiographic artefact: a text that forces modern scholarship to reassess its narratives. Once dismissed as fragmentary or “magical,” Mesopotamian medicine now appears as systematic, encyclopedic, and foundational.⁸³ Its head-to-foot structure predates Greek nosology, while its integration of therapy and ritual complicates modern binaries of rational versus irrational medicine. In this sense, the Encyclopedia bridges the gap between ancient healing practices and the long tradition of medical reference works that culminated in Galen, Celsus, and medieval encyclopedists.

The NME is therefore more than a relic of Assyrian scholarship. It is a milestone in the global history of medicine, the first surviving attempt to codify the human body into text, to order sickness and healing into a totalizing framework. Its rediscovery not only enriches our understanding of Mesopotamian thought but also reshapes the genealogy of medical knowledge itself.

Appendix

Notes

- British Museum, “Reconstructing a 2,500 year old medical encyclopaedia,” accessed September 29, 2025, https://www.britishmuseum.org/nineveh-medical.

- Krisztián Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads’: On the Serialisation of the Therapeutic Corpus at Nineveh,” KASKAL n.s. 1 (2024): 171–200.

- Ibid., 174–76.

- Ulrike Steinert, ed., Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues: Medicine, Magic and Divination (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 49–54.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 179–82.

- Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, trans. Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 233–39.

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 – 323 BC, (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), 91–93.

- Francesca Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 71–73.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 61–67.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 174–78.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 240–42.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 67.

- Markham J. Geller and Strahil V. Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts: The Nineveh Treatise (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), 40–43.

- Ibid., 42.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 182–89.

- JoAnn Scurlock, Sourcebook for Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014), 42–48.

- Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing, 69.

- Van De Mieroop, King Ashurbanipal, 145.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Ibid.

- Ulrike Steinert, “Digital Assyriology and the Reconstruction of Ancient Medicine,” Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 110 (2020): 122–25.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 186–87.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 55–59.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, 39–41.

- Ibid., 43–45.

- Ibid., 46–52.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 75.

- Heinrich von Staden, Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 113–16.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 77–81.

- Ibid., 42–43.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, 50.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 85–89.

- Ibid., 92.

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 70–71.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 245–47.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 54–55.

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 68.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, 52.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 61–67.

- Ibid., 64.

- Ibid., 66.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 186–87.

- Ibid., 171–200.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 238–42.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 49–87.

- Ibid., 52.

- Ibid., 77.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 101–106.

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 71–72.

- Paul Ghalioungui, The Ebers Papyrus (Cairo: Academy of Scientific Research, 1987), 12–17.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, vii–xii.

- Ibid., 40–45.

- Ibid., 46–48.

- Ibid., 49–52.

- Ibid., 52–54.

- Ibid., 54–55.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 57.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 238.

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 71–73.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Krisztián Simkó, “Ancient Healthcare Fit for a King,” British Museum Blog, November 30, 2021, https://blog.britishmuseum.org/ancient-healthcare-fit-for-a-king/.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, 32–39.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 49–52.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 42–48.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, 32–39.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 74–77.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 252–55.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 68–72.

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 3–6.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Ibid.

- Bottéro, Mesopotamia, 245–47.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 52–54.

- Rochberg, Heavenly Writing, 71–73.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 171–200.

- Geller and Panayotov, Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts, vii–xii.

- British Museum, “Reconstructing.”

- Scurlock, Sourcebook, 42–48.

- Simkó, “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads,’” 171–200.

- Steinert, Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues, 49–87.

Bibliography

- Bottéro, Jean. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Translated by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- British Museum. “Reconstructing a 2,500 year old medical encyclopaedia.” Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/nineveh-medical.

- Geller, Markham J., and Strahil V. Panayotov. Mesopotamian Eye Disease Texts: The Nineveh Treatise. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020.

- Ghalioungui, Paul. The Ebers Papyrus. Cairo: Academy of Scientific Research, 1987.

- Rochberg, Francesca. The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Scurlock, JoAnn. Sourcebook for Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2014.

- Simkó, Krisztián. “‘Weaving Together Loose Threads’: On the Serialisation of the Therapeutic Corpus at Nineveh.” KASKAL n.s. 1 (2024): 171–200.

- ———. “Ancient Healthcare Fit for a King.” British Museum Blog. November 30, 2021. https://blog.britishmuseum.org/ancient-healthcare-fit-for-a-king/.

- Steinert, Ulrike, ed. Assyrian and Babylonian Scholarly Text Catalogues: Medicine, Magic and Divination. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000 – 323 BC. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- von Staden, Heinrich. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.