Across ancient civilizations, from the dialogues of Plato to the bureaucracies of Han China, the regulation of technology was neither incidental nor benign. It was a moral, political, and existential strategy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power, Morality, and the Geometry of Innovation

Long before the roar of modern industry, the hum of ancient ingenuity echoed through marble forums, temple halls, palace libraries, and imperial foundries. Across the cradles of civilization, the technologies we often view as purely mechanical were anything but—they were bound to the moral, political, and sacred orders of the day. From the democratic tension of Greek invention to the Roman obsession with order and utility; from the priestly science of Egypt and the astronomical codes of Mesopotamia; from China’s carefully guarded innovations to the ghostly traces of mechanisms long since erased, ancient technology was never neutral. It was governed, restricted, elevated, and sometimes deliberately forgotten.

We explore the ethical and ideological frameworks that shaped technological development in five ancient arenas. In Greece and Rome, we examine how questions of virtue, slavery, and political order determined what machines were built—and for whom. In Egypt and Mesopotamia, we trace how divine authority and sacred geometry linked knowledge to power and ritual. In China, the state’s role as both guardian and censor of innovation reveals an early form of technological monopoly rooted in moral governance. Finally, in The Lost Engines of the Ancient World, we confront the silences: the marvels that vanished, the knowledge that withered, and the persistent myth that our ancestors did not dream as we do.

The past did not lack imagination. It was bound by intention. And to trace the lines of those intentions is to glimpse not only what ancient peoples made, but why they made it, for whom, and at what cost.

Greece and Rome: Moral and Political Boundaries

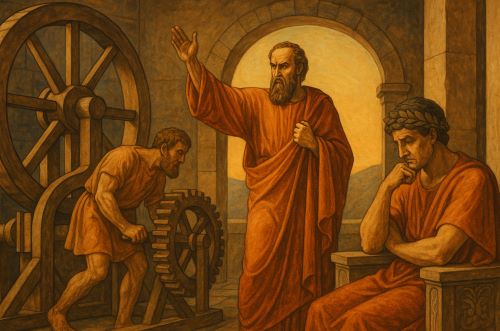

Plato and Technological Censorship

In the cavernous architecture of The Republic, Plato constructed a world of ideals more than mechanisms. Yet in his philosophical scaffolding, one finds striking evidence of what we might call technological censorship: a deliberate curtailment of certain crafts, inventions, and artistic tools deemed corrosive to the moral harmony of the state. The guardians of his city were not only to be shielded from corrupting stories but also from tools and devices that might nourish unchecked curiosity or destabilize hierarchy. In a society obsessed with order, the forge and the lyre could be equally subversive.

This policing of the soul was not merely metaphorical. Plato envisioned a society in which even the production of certain kinds of objects had to be regulated, lest their form fail to reflect the eternal ideals they were meant to imitate. The craftsman who strayed from form, just like the poet who sang out of turn, was a danger to the polis. He thus advocated for what we might now call a techno-ethical state: not one that bans tools per se, but one that imposes moral limits on their design and dissemination.1

Equally critical is his concept of the noble lie, a narrative device sanctioned by the rulers to maintain social cohesion. Here, technology itself could be mythologized or obscured for political ends. In Plato’s world, not all truths were for public consumption. Some mechanisms, whether poetic or practical, had to be hidden behind allegory or outright fiction to preserve collective virtue.2 This was less about fear of the machine than fear of the mind unleashed.

Roman Engineering and the Hidden Empire

Where the Greeks questioned whether technology should exist at all in certain forms, the Romans more often asked who should own it. In a civilization whose grandeur was carved in stone and poured in concrete, the most consequential tools were rarely democratized. Indeed, they were classified, closely guarded within military ranks or elite engineering circles. The famed architecti of the empire did not simply build aqueducts and roads; they managed the strategic secrets of an infrastructure that projected Rome’s dominion across continents.

Roman concrete, for example, was more than a building material. Its water-resistant properties allowed harbors to stretch into the sea and cities to rise in defiance of natural erosion. Yet the precise formula was not broadly shared. Though manuals like those of Vitruvius survive, they are less instruction manuals and more coded appeals to a learned elite.3 His De Architectura presumes a reader already within the fold, a technical priesthood rather than an open workshop.

This hoarding of technical knowledge was no accident. It served the imperial logic of control: to restrict technological literacy was to maintain Rome’s architectural and military supremacy. Machines such as the ballista and the repeating catapult were engineered innovations, but more importantly, they were state weapons, classified both physically and ideologically. The technological opacity served not just as military defense, but as epistemic domination. To know how to build was to wield power. Rome made sure not everyone could.

Egypt and Mesopotamia: Sacred Circuits of Knowledge

Priesthood as Gatekeepers

Long before the blueprints of Vitruvius, another form of techno-regulation flourished along the Nile and the Euphrates. In both ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, the custodians of knowledge were not engineers but priests. The temples, massive and enigmatic, were more than places of worship; they were data centers of early civilization. Astronomy, medicine, hydraulics, and mathematics converged beneath their columns, but access was tightly restricted.

The technologies these priestly elites controlled were not rudimentary. Water clocks, for instance, allowed for complex calendrical rituals; irrigation systems transformed barren landscapes into agricultural abundance. Yet these were not communal assets. Rather, they were instruments of divine legitimacy. By maintaining exclusive command over the workings of time and water, the priesthood perpetuated its authority as the earthly voice of cosmic order.4

Innovation in this context did not mean progress; it meant proximity to the gods. To reveal a new technique was to stake a spiritual claim. As a result, technological advancement was not suppressed outright, but carefully metered, curated through ritual channels, and preserved within temple archives. The sacred and the scientific were entangled in a way that rendered dissident invention almost unimaginable.

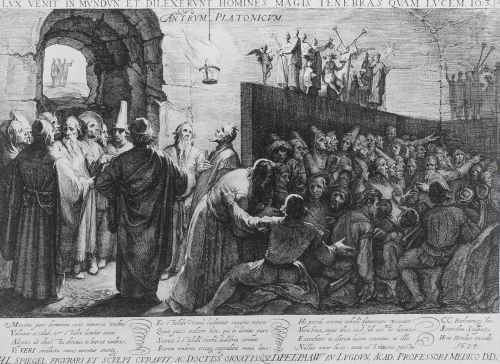

Myth as a Regulatory Tool

Such control was reinforced not only through bureaucracy but through narrative. Across the ancient Near East, myths served as regulatory devices: cautionary tales warning of overreach and hubris. The Tower of Babel story in the Hebrew Bible exemplifies this motif. Here, architecture itself becomes suspect, a stairway to heaven built by men who forget their place. Their punishment is linguistic fragmentation, a divine strike against collective ambition.5

In Greek mythology, a similar caution is found in the figure of Prometheus, whose theft of fire is less a tale of human advancement than one of divine transgression. Fire, the primordial technology, is not gifted freely; it must be stolen, and the thief must suffer. These stories, passed through centuries, taught that knowledge had a cost, and that cost was often paid in blood or exile. The lesson was not to cease inventing but to know where the line lay and who drew it.

China: Empire, Ethics, and Technological Monopoly

The Salt and Iron Debates

In imperial China, the regulation of technology was neither purely spiritual nor purely militaristic; it was ideological. During the Han dynasty, a pivotal moment arrived in 81 BCE with the famous Salt and Iron debates. These were not arcane philosophical musings but vigorous court arguments about whether key industries should remain under state control. The core issue: were private inventors and merchants a danger to virtue?

Advocates for state monopolies argued that allowing innovation in such sectors as salt mining and iron smelting would encourage greed and destabilize the moral order. Others countered that suppressing creativity in the name of virtue merely entrenched authoritarianism.6 These debates anticipated modern concerns about the trade-off between innovation and social harmony. The Han government ultimately opted for control—ensuring that technical progress aligned with imperial interests rather than individual gain.

Gunpowder and Its Silencing

Few cases better illustrate the selective suppression of innovation than the Chinese handling of gunpowder. Discovered during the Tang dynasty and refined under the Song, its explosive potential was recognized immediately, not as a tool for civil advancement, but as a weapon. While Buddhist alchemists and Daoist tinkerers may have stumbled upon it seeking immortality, the state swiftly seized its utility.

Gunpowder’s public diffusion was deliberately curtailed. Its recipe was guarded, its production centralized, its applications confined to war and spectacle. For centuries, China possessed the most powerful explosive compound on earth, and yet refrained from industrializing it. Only through the violence of the Mongol conquests did its secret begin to leak into the wider world.7 The deliberate opacity preserved national security but also foreclosed avenues of transformation that would later define Western modernity.

The Lost Engines of the Ancient World

Heron and the Sidelining of Innovation

In the annals of unrealized futures, few stories haunt the historian like that of Heron of Alexandria. A polymath of the first century CE, Heron devised an early steam engine—the aeolipile, a rotating sphere powered by heated water vapor. It was, in essence, the blueprint of the Industrial Revolution. And yet it found no traction beyond the temple theatrics for which it was designed.

Why did this prototype of mechanized power remain a curiosity? The answer likely lies in the broader social logic of the ancient world, in which surplus labor was abundant and institutional inertia discouraged transformation. Some scholars speculate that Heron’s invention was intentionally marginalized, deemed too disruptive to the prevailing balance of temple authority, slave economy, and elite patronage.8 In this reading, the aeolipile becomes less a missed opportunity than a suppressed one.

Greek Fire: Weaponized Secrecy

Not all ancient technologies vanished by accident. The case of Greek fire, the fearsome incendiary weapon of the Byzantine navy, reveals a different kind of regulatory logic, one rooted in strategic concealment. Greek fire was not merely a substance; it was a doctrine of control. Its formula was never shared beyond a trusted inner circle, and even allies were kept at arm’s length.

This obsession with secrecy proved effective. Greek fire helped preserve the empire against Arab sieges and inspired generations of awe. But in the end, its recipe was lost. The very success of its secrecy ensured its extinction. Here, regulation was not moral or theological; it was existential. Technology was not for public utility, but for survival. The lesson was clear: some tools must burn in silence.

Conclusion: Regulating the Future by Remembering the Past

Across ancient civilizations, from the dialogues of Plato to the bureaucracies of Han China, the regulation of technology was neither incidental nor benign. It was a moral, political, and existential strategy. Each society set its boundaries, drew its lines, and told its stories to preserve a fragile equilibrium. Innovation was not a virtue in itself, but a force to be mastered, masked, or morally weighed.

We live today in a world where technological acceleration often outruns ethical reflection. Yet the ancients remind us that every machine, every formula, every flame has a context. If we forget that, we risk becoming Prometheus without a myth, Heron without a temple, or worse: stewards of fire with no memory of the cost.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Plato, The Republic, Second Edition, trans. Allan Bloom (New York: Basic Books, 1991), 377b–403c.

- Ibid., 414b–415d.

- Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- A. Broadie and J. Macdonald, “The Concept of Cosmic Order in Ancient Egypt in Dynastic and Roman Times,” L’Antiquité Classique 47, no. 1 (1978): 106–28.

- Genesis 11:1–9, The Hebrew Bible.

- Michael Loewe, “The Debate on Salt and Iron (81 B.C.),” in Crisis and Conflict in Han China (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1974), 61–89.

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 5, Part 7 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 12–24.

- Lucio Russo, The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BCE and Why It Had to Be Reborn (Berlin: Springer, 2004), 118–120.

Bibliography

- Broadie, A., and J. Macdonald. “The Concept of Cosmic Order in Ancient Egypt in Dynastic and Roman Times.” L’Antiquité Classique 47, no. 1 (1978): 106–28.

- Loewe, Michael. Crisis and Conflict in Han China. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1974.

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 5, Part 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Plato. The Republic, Second Edition. Translated by Allan Bloom. New York: Basic Books, 1991.

- Russo, Lucio. The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BCE and Why It Had to Be Reborn. Berlin: Springer, 2004.

- The Hebrew Bible. Genesis 11:1–9.

- Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Noble Howe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.31.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.