The period of the Reformation (roughly 1500-1700) witnessed an unprecedented wave of changes in religion, thought, society, and politics throughout the world.

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 09.11.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

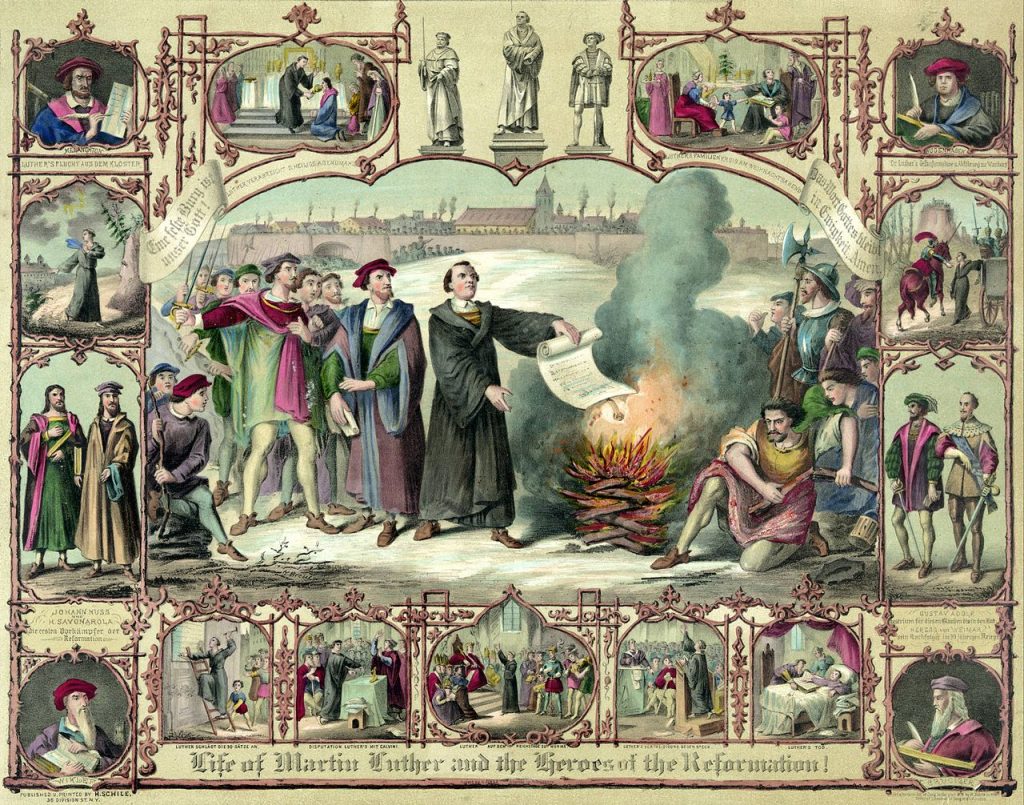

When Martin Luther circulated ninety-five theses criticizing various practices of the Roman church in October of 1517, his only intention was to start a productive debate with his academic colleagues. Much to his surprise, his criticisms spread like wildfire throughout Europe, inciting a movement we now know as the Reformation. The catalyst for this remarkable event was the printing press; Luther’s controversial ideas were printed and reprinted within weeks of their first circulation, and copies were bought, read, and shared by eager audiences throughout Europe. In this, Martin Luther became the first European intellectual to “go viral.”

The period of the Reformation (roughly 1500-1700) witnessed an unprecedented wave of changes in religion, thought, society, and politics throughout the world. Thanks to Luther’s viral ideas, the most stable authority known to Europeans in the Middle Ages – the Christian church – was challenged, shaken, and eventually splintered. Luther’s direct and simple message that Christians were saved through faith alone licensed ordinary Christians to assume direct responsibility for their salvation rather than relying on the church, and they responded by reshaping medieval Christianity according to their needs. Shocked by these many changes, secular and religious authorities spent the following two centuries attempting to control this unruly religious public in various ways.

None of these changes could have occurred without print. Scholars, pastors, theologians, princes, and others depended on printed works to defend, promote, condemn, and control the religious and changes unleashed during the Reformation. Yet while scholars have long known that the Reformation was impossible without print, comparatively little attention has been paid to the ways in which these religious changes shaped the medium of print itself. The religious changes in this period created a host of new problems and challenges for religious thinkers and leaders at this time, and print culture as it existed in 1517 was not sufficient to solve them. As such, religious figures developed new printing techniques, new printed materials, and more efficient marketing strategies to ensure that their denominations survived and thrived.

The documents below give a small sample of the different ways in which religious change drove the development of print culture. Through them, you will gain a better understanding of the immense challenges caused by religious change in this period, and the different ways in which print culture was shaped and re-shaped in order to meet them.

The Printing Press and Medieval Religion

The ability of the printing press to produce texts on a massive scale was appealing for religious leaders in the Middle Ages. Since the eleventh century at least, religious thinkers sought out and promoted any new technology that would help them reach a large audience as quickly as possible. By the later Middle Ages, the church was particularly interested in mass-producing materials to support lay devotion, such as prayer books, devotional images, and pilgrim badges.

Few devotional items showed the intersection between religion and print better than indulgences. Originally conceived in the twelfth century, an indulgence was a spiritual benefit (e.g., forgiveness of sin or a reduction of one’s time in purgatory) in return for some sort of service rendered to the Church. By the sixteenth century, the mere purchase of an indulgence was sufficient to earn this reward, and the indulgence trade was a major source of revenue for the papacy, which sold them to fund the building of churches, support important local causes, and – as the example here – fund a new crusade against the Turks.

Printers were excited to publish these texts, as they represented major work orders from a reliable institution. This was especially true in Germany, where ninety percent of the surviving fifteenth-century printed indulgences were made. These texts were inexpensive and easy to print: they required no more than a single sheet, and included only a description of the indulgence offered and an acknowledgement of the gift received. As in this example here, a blank space was left in which the indulgence seller would write the name of the purchaser.

Flugschriften – Writings that Fly

Luther despised the indulgence trade, but he recognized the importance of making religious material widely available as quickly as possible. As the Reformation grew, Luther developed a new form of printed work to support it: the pamphlet. Luther’s pamphlets – known in German as Flugschriften (flying writings) – were fairly short in length, easy to read, inexpensive to print, and quickly produced in a matter of days. Moreover, Luther wrote many of his pamphlets in German, which greatly increased the potential audience for his work. As such, they were the perfect vehicle for his public campaign against what he considered the tyrannical Roman church.

Pamphlets proved to be astounding successes, for printers and readers alike. Much like indulgences, pamphlets were cheap and easy to produce, and Wittenberg printers were happy to print Luther’s works as soon as he finished them. Overnight, Wittenberg became of the leading print centers in Germany, almost entirely because of Luther’s prolific output. Readers responded to them as well, Flugschriften were affordable, easy to read, and did not take up much space. For many, a Luther pamphlet was the first book anyone in their family had ever owned.

The papacy opened a formal investigation of Luther’s ideas in January of 1520. Over the remainder of that year, Luther responded by publishing three important pamphlets that laid out his understanding of “true” Christianity and the ways in which the Roman church had perverted it. The pamphlet shown here, De captivitate babylonica ecclesiae (On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church), was the second in this series. In this work, he argued that the Roman church had perpetrated a blatantly false understanding of the sacraments as the only point of access to the divine. According to Luther, the church used this sacramental control to keep laypeople from reading the Bible. He revised the list of sacraments from seven to three (later reduced to two, baptism and communion), and insisted that they were not magical ceremonies performed only by priests, but were freely-given manifestations of God’s grace for all believers. Written only in Latin, it represented Luther’s most radical assault on the medieval church to date, and signaled that reconciliation with Rome was likely impossible.

Building Communities of Faith

As Christendom broke apart into competing churches, religious thinkers and leaders struggled to find ways to build up thriving faith communities that would provide support, comfort, and a sense of stability in an increasingly chaotic religious environment. Both Protestants and Catholics sought to do this by vigorously promoting the publication of a range of materials that were intended to be used communally. The items here represent two of the most important examples: music and visual art.

The singing of hymns, psalms and other spiritual songs was especially important for Protestants. Lutherans considered congregational singing in four-part harmony essential for building up the faith and morale of a church. More radical Protestant sects like the Anabaptists and the Bohemian Brethren also used songs as a way to cultivate a shared identity and resolve in times of persecution. Whatever their intention, these groups produced their own versions of hymnals and spiritual songbooks to bind their followers together. Shown here is a Lutheran songbook from the late sixteenth century. It includes a version of Luther’s famous hymn, Ein fester Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is our God), which has served as a rallying cry for Lutherans from the sixteenth century to the modern day.

The other item is a typical devotional image of a saint produced by the Catholic church. By the late sixteenth century, Catholics turned increasingly to spectacular visual displays such as images, processions, and church building to counteract Protestantism’s stripped-down version of medieval Christianity. In particular, Catholic thinkers encouraged the mass production of images showing events from the lives of saints and of Christ, which could be used as devotional focal points for Catholic laity. This was especially important in the colonies in the Americas, where missionaries faced the challenge of converting and instructing indigenous peoples who did not know any European language.

Shown here is an early printed image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who was said to have appeared to a converted Aztec peasant in the early sixteenth century outside of present-day Mexico City. The engraving also depicts Juan Diego, the converted Aztec peasant to whom the Virgin is said to have appeared in 1531. A century later, the Church aggressively promoted the Virgin’s cult on an international scale, using printed images like this one to standardize its iconography. This early version of the image includes a good deal of imagery that was more closely associated with the Aztec corn goddess Tonantzin, whose cult the Virgin of Guadalupe absorbed.

Education and Censorship

Education was critically important during the Reformation. Protestants insisted that all Christians be able to read the Bible, which made it necessary to improve literacy in all social levels. Members of the Jesuit order made education one of their signature causes, so that Jesuit clergy would be able to provide whatever ministry would be needed in any setting.

At the same time, the need to promote knowledge was balanced by the need to control it. Print’s ability to reach a large audience quickly also meant that it was extremely difficult to keep conflicting ideas contained, but religious and secular authorities did their best to limit their subjects’ exposure to any ideas they considered dangerous. The items below give a sense of how religious thinkers and leaders used print to encourage and regulate the dissemination of knowledge.

In the Reformation era, everyone prioritized early childhood education as a means of ensuring their church’s survival. Members of all Christian sects were concerned above all with how well their children knew the basic tenets of the faith such as the Ten Commandments, the creeds, and the Lord’s Prayer. Then as now, educating the young could be a difficult challenge, so religious thinkers constantly experimented with different publications to instruct young people in these religious concepts. In the first item below, Gimel Bergen von Lübeck, a printer operating in the German city of Dresden, made his own attempt in 1586, pairing images with short poems to help children learn the “holy Apostles’ whole teaching, deeds, and way of life.”

The second item is an example of a censored work. Though censorship was practiced by all denominations, it is most commonly associated with the Catholic Church. Censorship was one of the primary responsibilities of the Office of the Inquisition, an official arm of the church charged with discovering and eradicating heresy. Printers had encouraged censorship from the earliest days of the medium as a means of controlling the industry, so many were happy to work closely with the Inquisition by publishing the Catholic church’s index of banned books. However, banning a book was considered a last resort; in many cases, like the prayer book shown here, the Inquisition preferred to “save” a book from destruction by redacting only the offensive material.

Expansion and Conversion

European expansion into North and South America created significant new problems for religious leaders and thinkers, who unexpectedly faced untold numbers of indigenous populations who knew nothing of Christianity. The intense competition between the Christian sects in Europe led to a massive wave of missionary work, as Protestants and Catholics raced across the globe to win these unconverted masses over to their side. To succeed, they developed a range of new publications to streamline and simplify this complex task.

The most significant hurdle for missionaries to climb was a linguistic one, so they diligently worked with indigenous contacts to compile word lists and dictionaries to aid conversion efforts. French missionaries were especially active linguistic compilers; they often appended dictionaries to the accounts of their missionary activity that were printed back in Europe, such as the Huron dictionary displayed here. In this way, missionaries could both inform the public at home about the progress of Christianity in the Americas at the same time as they prepared the way for future generations of missionaries.

Missionaries faced an altogether different problem with the West Africans brought over to the Americas as slave labor. Unlike indigenous American populations, European plantation owners made a conscious decision to withhold Christianity from the slaves by refusing missionaries any access to them. In response, clergy from all sects turned to print to reveal what they considered a horrendous spiritual crime to audiences at home. The work shown here is one such report by Morgan Godwyn, an Anglican clergyman and missionary who worked in British colonies in America and the Caribbean. In the excerpts shown here, Godwyn defends his claim that slaves are fit for conversion to Christianity and excoriates slave owners for failing in their essential Christian duty.

War and Chaos

Religion and politics were closely united when the Reformation began, so it is not surprising that the religious turmoil of the Reformation led to a wave of violence and conflict, as the competing sects struggled for political and social control across the globe. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the decision to join one Christian sect or the other often carried consequences of loss of property, exile, and death. Defense of “the true religion” became a pretext for resistance, rioting, and open war. Faced with this constant state of conflict, Christians of all kinds turned increasingly to print to come to terms with the immense anxiety and chaos caused by these religious changes.

The religious world of the Reformation was generally an intolerant one. Many Protestants as well as Catholics believed that they could not safely practice their own faith so long as the other was being practiced openly nearby, so at times state authorities (and occasionally mobs of civilians) worked to cleanse their territory of all traces of competing sects. This was most apparent in territories controlled by Calvinists, who believed that the use of images in worship – a hallmark of Catholicism – was proof of idolatry. Calvinist mobs were known to destroy Catholic art and architecture throughout the sixteenth century. The author Richard Verstegen, an English Catholic, published an illustrated account of atrocities committed against Catholics, with special emphasis on the Huguenots in France and the Protestants in England.

The Reformation also led to the most devastating war Europe had ever known: the Thirty Years’ War. Begun over a dispute over whether the kingdom of Bohemia would be ruled by a Protestant or a Catholic, the war eventually dragged in combatants from across Europe, with the German lands serving as the main battlefield. Mercenary armies did the majority of the fighting, and often resorted to pillaging the countryside when they were not paid. The war ended in a relative stalemate, but the incalculable devastation of Germany was a traumatic experience for Christians everywhere. Even outside observers were compelled to make some sense of the carnage. The second item, a work by the English preacher and theologian Philip Vincent, sought to draw some spiritual lesson from the horrific conflict. His account of the war was accompanied by a series of engravings detailing the atrocities committed, primarily by Catholic soldiers.

Calling for Tolerance

Calls for religious tolerance had been heard since the earliest days of the Reformation, but – save for a few exceptions – these calls did not gain much traction until after the trauma of the Thirty Years’ War. During the second half of the seventeenth century, the idea that being a good citizen was more important for peace and stability than being a good Lutheran, Calvinist, or Catholic became increasingly more prominent in intellectual circles.

These views were still considered extremely controversial in most places, but some intellectuals were determined to give them a public hearing. Many chose to publish these ideas in anonymous open letters, which would start the conversation about toleration without bringing any consequences upon themselves. The famous English philosopher John Locke followed this route with his Letter Concerning Toleration, which was originally published anonymously in Latin in Amsterdam in 1689.

In this letter, Locke argued that the state had no power or authority to intervene in matters of religion, which was the purview of the individual’s conscience. Although he doubted that atheists or Catholics could ever be good citizens, his call for religion to be separated from politics represented a major break with the views of the early reformers. His concept of religious tolerance would be further developed over the coming century, most notably by the framers of the United States Constitution, who used it as the basis for the formal separation of church and state, the first time in human history such a thing had ever been done.

Selected Sources

- Cameron, Euan. The European Reformation. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Edwards, Mark U. Printing, Propaganda and Martin Luther. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

- Febvre, Lucien and Henri Martin. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800. London, NLB, 1976.

- Lockhart, James, and Stuart B. Schwartz. Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. New York: Viking, 2004.

- Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Rice, Eugene F. and Anthony Grafton. The Foundations of Early Modern Europe, 1460-1559. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994.

- Round, Philip. Removable Type: Histories of the Book in Indian Country, 1663-1800. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

By Dr. Christopher Fletcher

Head Researcher, Medieval Scientific History

Centre national de la recherche scientifique