His treatment of the battle is evocative of the Iliad.

By Dr. Christopher Pelling

Regius Professor of Greek Emeritus

University of Oxford

It is late afternoon on the day of the battle. The result is no longer in doubt; most of the killing has already happened, and attention now turns to the harrying of the fleeing Persians:

Νικῶντεςδὲτὸμὲντετραμμένοντῶνβαρβάρωνφεύγεινἔων, τοῖσιδὲτὸμέσονῥήξασιαὐτῶνσυναγαγόντεςτὰκέρεαἀμφότεραἐμάχοντο, καὶἐνίκων ̓Αθηναῖοι. φεύγουσιδὲτοῖσιΠέρσῃσιεἵποντοκόπτοντες, ἐςὃἐπὶτὴνθάλασσανἀπικόμενοιπῦρτεαἴτεονκαὶἐπελαμβάνοντοτῶννεῶν. καὶτοῦτομὲνἐντούτῳτῷπόνῳὁπολέμαρχοςΚαλλίμαχοςδιαφθείρεται, ἀνὴργενόμενοςἀγαθός, ἀπὸδ’ ἔθανετῶνστρατηγῶνΣτησίλεωςὁΘρασύλεω·τοῦτοδὲΚυνέγειροςὁΕὐφορίωνοςἐνθαῦταἐπιλαμβανόμενοςτῶνἀφλάστωννεός, τὴνχεῖραἀποκοπεὶςπελέκεϊπίπτει, τοῦτοδὲἄλλοι ̓Αθηναίωνπολλοίτεκαὶὀνομαστοί.

Here again they [the Athenians, or perhaps the Athenians and Plataeans] were triumphant, chasing the routed enemy, and cutting them down until they came to the sea, and men were calling for fire and taking hold of the ships. It was in this phase of the struggle that the War Archon Callimachus was killed, fighting bravely [lit. having become, or having behaved as, a good man], and also Stesilaus, the son of Thrasylaus, one of the generals; Cynegirus, too, the son of Euphorion, had his hand cut off with an axe as he was getting hold of a ship’s stern, and so lost his life, together with many other well-known Athenians.

Herodotus 6.113-14, trans. de Sélincourt

And the heroic death of Cynegirus, the brother of Aeschylus, duly became a famous exemplum for later writers.

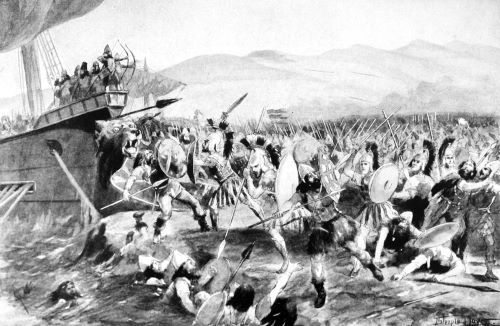

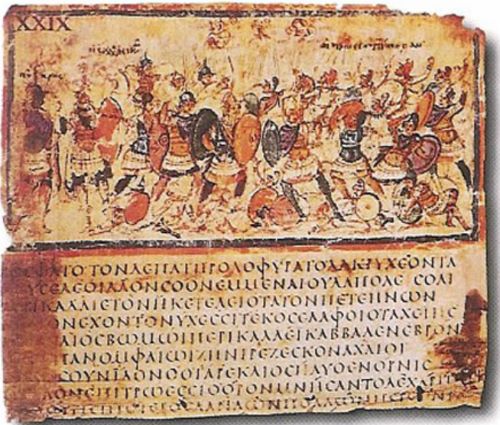

There is no reason to doubt that something like this happened. There must surely have been fierce fighting by the ships; seven of them were captured (115.1), and given the expanse of beach that the fleet will have been covering and the time it must have taken to get men on board – probably horses too, though that is disputed – we would assume that the Athenians were not going just to wave the Persians off and wish them a nice voyage home. We know from Pausanias (1.15.3) that the fighting by the ships was one of the themes of the Marathon painting in the Stoa Poikile; if it is right to think that the Brescia sarcophagus is based on the Stoa painting,1 then we can see Cynegirus there with his hand gripping the stern, and a Persian lifting the axe ready to strike. This was already part of the story when Herodotus came to it.

The way he treats it is still interesting. For one thing, there is the speed with which he describes the fighting – much quicker than the narratives of Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea. In the two short sentences before this extract the Greek centre has just done badly, the wings have done well, and the pincer has closed on the Persian centre as it pushes ahead; that is all. To judge from what we hear of the Stoa Poikile, the main slaughter came in an interim phase, when the Greeks pushed the Persians back into a marsh – the marsh that is so much discussed in the topographical literature2 – and the Persians fell over one another as they stumbled in (Paus. 1.15.3, 32.7); nothing of that here, despite the opportunity to prefigure an element of the battles ten years later,3 in this case the lethal turmoil in the waters of Salamis as the non-swimming Persians met their end (8.89.2). Why?

One of the reasons might be a muted hint of what is on its way to becoming an important theme, earth and water, land and sea: the earth and water that Darius has demanded, and that so many states have already given4 (including, at least at first, the Athenians themselves at 5.73.1-2);5 the earth and water that the Spartans have told the Persian heralds to get from the well into which they had been thrown (7.133.1); the land and sea that Artabanus will say are Xerxes’ greatest enemies (7.49.1); the land that Xerxes will turn into sea at Mount Athos and the sea that he will turn into land at the Hellespont; the land and sea that will eventually conspire together to wreck so much of the Persian fleet on the shore of Euboea (7.188-93).6 That will be when the sea throws the ships upon the land; here the land throws the Persians back upon the sea. That has more emblematic force than any marsh could convey.

Still, there must be more to it than that. Let us work from a small detail, the way the Greek fighters ‘called for fire’. That too links with the earth and water theme: ‘Darius had demanded earth and water…. Instead the Greeks give him fire’.7 But where would that fire come from? It is a long way from the Greek camp. A. R. Burn once conjured up a picture of camp-followers running behind the battle with braziers;8 that is not very plausible. Nor is there any mention of fire in our descriptions of the Stoa Poikile, nor is anything visible in the Brescia sarcophagus. No; that fire comes, not from the Greek camp, but from the Iliad: from the end of Book 15, when Hector is leading the charge upon the Greek ships:

῞Εκτωρδὲπρύμνηθενἐπεὶλάβενοὐχὶμεθίει, ἄφλαστονμετὰχερσὶνἔχων, Τρωσὶνδὲκέλευεν·“οἴσετεπῦρ, ἅμαδ’ αὐτοὶἀολλέεςὄρνυτ’ ἀϋτήν …”

Hektor would not let go of the ship where he had grasped it at the stern, gripping the poop-end in his hands, and he called out to the Trojans: ‘Bring fire, and raise the war-cry all together …’

Iliad 15.716-8, trans. Hammond

And there the fire would presumably be brought from the Trojan campfires in the plain, so memorably blazing at the end of Book 8 (553-65). There are no marshes in the Iliad, but a clear-cut topography of city, plain, and sea, and that is what we are also given here.

Nor is it just the fire that evokes the Iliad, nor even that thoroughly Homeric word κόπτω for ‘to smite’. Hector too grasps a ship just as the Greeks do now (notice the repeated ἐπιλαμβάνεσθαι in Herodotus);9 Hector too will not let go, just as Cynegirus will not let go.10 And what both Hector and Cynegirus grasp is the ἄφλαστον, or several of them in Herodotus’ odd plural. That is a very rare word indeed, translated by LSJ as ‘curved poop of the ship’ and by Janko as ‘a carved stern-post’:11 something similar is again visible on the Brescia sarcophagus. Outside these two passages the word only crops up in passages that are surely evoking the Iliad,12 just as this must be. And this, of course, is not just any old passage in the Iliad: it is the crucial moment of both poem and war, the height of Hector’s achievement – and yet the act that also begins the movement that will bring Achilles back to the fighting, sealing Hector’s own death and the fate of Troy. So in the Iliad it is glory, but glory that presages disaster and annihilation.

Marathon, then, this most heroic of battles, is described with appropriate epic resonance. This has been noticed, of course; Stein pointed out the specific allusion to οἴσετεπῦρ, and later commentators too talk about a ‘Homeric ring’ (Scott), or ‘Homeric overtones’, (Evans) or ‘the coloring lent by epic language’ (McCulloch),13 though the oddity of this ‘fire’ is not normally spelt out. It was spelt out back in 1969 in a brief note by J. R. Grant,14 but Grant grumpily summed up the implications as ‘Herodotus, it would seem, is adding bits of Homeric colour, and, in so doing, practising automatic writing at its purest, with a consequent loss of historical accuracy’. ‘Automatic writing at its purest’? I think we can be more generous than that.

It may be important here that Herodotus is already ‘in dialogue’ with previous versions of Marathon, possibly indeed including that of the Stoa Poikile (though that would be familiar only to Athenians and a few others); we can sometimes sense that the dialogue was quite pointed, for instance in the recurrent stress he gives to the role of the Plataeans. They are given a whole excursive chapter at 108, and then he emphasizes the solemn prayer that the Athenians now give in their five-year festivals for prosperity for ‘the Athenians and Plataeans’ (111.2); there is a corresponding stress on the role of the Plataeans in the fighting (111.1–2, 113.1). That may well carry a pointed hint forward to the events of 431 and 427, culminating in the destruction of Plataea at Spartan hands: after all, Herodotus has just gone out of his way to introduce that contemporary Peloponnesian War perspective with those remarks on the evils that awaited Greece during the next three generations, ‘some coming from the Persians, some from the leading states themselves as they battled for supremacy’ (6.98.2). If so, the implication may not be so simple as a contrast with the good faith shown between Athens and Plataea in recent events and the bad faith of Sparta towards Plataea back then.15 Athens did not cover herself in glory in the 427 sequence either, and any Herodotean recrimination over these modern events may be more broadly aimed. More certainly, the passage also corrects the recurrent Athenian boast that ‘alone of the Greeks’ we took on the Persians in 490 as the champion of freedom. That is a staple of oratory, as other papers in this volume bring out;16 we find it in the Athenians’ speech in Thucydides (1.73.4); we find it already in the tendentious Athenian speech in Herodotus himself, 9.27.5.17 The ‘legend’ of Marathon is already forming within Herodotus’ own pages: within eleven years it has already become rhetorically exemplary, and rhetorically misrepresented.18

The Stoa Poikile, we happen to be told, did not suppress the Plataeans (Paus. 1.15.3), nor even in some moods did all Athenian orators: the Stoa made sure that the Plataeans were recognizable by their Boeotian headgear, or so says Apollodorus, the deliverer of the speech Against Neaera, intent in that rhetorical context on playing up rather than down the ancestral debt of the Athenians to Plataea ([Dem.] 59.94). What the Stoa was also already doing, surely, was to intimate that elevation of the Marathon campaign to ‘heroic’ status: not just heroic in a loose, ‘their finest hour’ sort of sense, but in the sharper way of representing it as a counterpart of the heroic deeds of Homer and beyond. That was why Marathon could take its place in the Stoa alongside depictions of the Amazonomachy and the Trojan War; that too was why the Stoa could include in the Marathon panel the local hero, Theseus, Athena, and Heracles (Paus. 1.15.3). Nor was it just the Stoa Poikile, nor just Marathon: the ‘new Simonides’ – by now not so new as all that – shows a very elaborate linkage of the Plataea campaign to the Homeric world, with all that material on Achilles.19 With Marathon, we can once again see that ‘Homerization’ forming in Herodotus’ own pages, with the Athenians moving swiftly in their 9.27 speech from the Heracleidae, the Seven against Thebes, the Amazons – the stuff of funeral orations, of course – to Marathon itself.

So: was Grant right, and is this just old hat, ‘automatic writing at its purest’, with Herodotus’ Homerizing just a clichéd reflex as he does what others have been doing for fifty years already? I argued a few years ago that Herodotus’ relation to Homer could be more thoughtful, not just a matter of ‘colouring’ or ‘flourishes’ but an exploration of how far values and events and achievements had changed, how and how far the ‘epic’ or the ‘heroic’ could still be achieved in the world of the polis.20 I did not say much about Marathon in that paper, but if there was anything in that argument it would be odd if Marathon of all battles did not fit. I think it does: here too we can see ways in which the narrative develops themes which look both backwards and forwards, backwards to Homer and forwards to the more disquieting events of Herodotus’ own day. This is the stuff of legend and of glory, yes; the finest hour, yes; but it plays against a world where so much had changed, and was changing still.

Let us start with the speech of Miltiades to Callimachus. The generals are split, and the vote of the polemarch becomes crucial; Miltiades is trying to win Callimachus to his side. There are all sorts of historical issues there that cannot be discussed here,21 not least the question what exactly the disagreement was about: if Miltiades was urging that they should fight straight away, then it is odd that they waited for several days; if the other side was arguing that they should not, then they must have known that they might have to, if the Persians tried to force their way past them on one of the possible routes towards Athens. One naturally wonders if the disagreement was really about ‘whether or not to wait for the Spartans, that is if we possibly can’. But Herodotus simplifies it to a sharp ‘to fight or not to fight’ question.

̓Ενσοὶνῦν, Καλλίμαχε, ἐστὶἢκαταδουλῶσαι ̓Αθήναςἢἐλευθέραςποιήσανταμνημόσυνονλιπέσθαιἐςτὸνἅπανταἀνθρώπωνβίονοἷονοὐδὲ ̔Αρμόδιόςτεκαὶ ̓Αριστογείτωνλείπουσι. νῦνγὰρδή, ἐξοὗἐγένοντο ̓Αθηναῖοι, ἐςκίνδυνονἥκουσιμέγιστον, καὶἣνμένγεὑποκύψωσιτοῖσιΜήδοισι, δέδοκταιτὰπείσονταιπαραδεδομένοι ̔Ιππίῃ·ἣνδὲπεριγένηταιαὕτηἡπόλις, οἵητέἐστιπρώτητῶν ̔Ελληνίδωνπολίωνγενέσθαι. κῶςὦνδὴταῦταοἷάτέἐστιγενέσθαι, καὶκῶςἐςσέτοιτούτωνἀνήκειτῶνπρηγμάτωντὸκῦροςἔχειν, νῦνἔρχομαιφράσων. ἡμέωντῶνστρατηγῶνἐόντωνδέκαδίχαγίνονταιαἱγνῶμαι, τῶνμὲνκελευόντωνσυμβαλεῖν, τῶνδὲοὔσυμβαλεῖν. ἢνμέννυνμὴσυμβάλωμεν, ἔλπομαίτιναστάσινμεγάληνδιασείσεινἐμπεσοῦσαντὰ ̓Αθηναίωνφρονήματαὥστεμηδίσαι·ἢνδὲσυμβάλωμενπρίντικαὶσαθρὸν ̓Αθηναίωνμετεξετέροισιἐγγενέσθαι, θεῶντὰἴσανεμόντωνοἷοίτέεἰμενπεριγενέσθαιτῇσυμβολῇ. ταῦταὦνπάνταἐςσὲνῦντείνεικαὶἐκσέοἢρτηται·ἢνγὰρσὺγνώμῃτῇἐμῇπροσθῇ, ἔστιτοιπατρίςτεἐλευθέρηκαὶπόλιςπρώτητῶνἐντῇ ̔Ελλάδι·ἢνδὲτὴντῶνἀποσπευδόντωντὴνσυμβολὴνἕλῃ, ὑπάρξειτοιτῶνἐγὼκατέλεξαἀγαθῶντὰἐναντία.

‘It is now in your hands, Callimachus,’ he said, ‘either to enslave Athens, or to make her free and to leave behind you for all future generations a memory more glorious than even Harmodius and Aristogeiton left. Never in our history have we Athenians been in such peril as now. If we submit to the Persians, Hippias will be restored to power – and there is little doubt what misery must then ensue: but if we fight and win, then this city of ours may well grow to pre-eminence amongst all the cities of Greece. If you ask me how this can be, and how the decision rests with you, I will tell you: we commanders are ten in number, and we are not agreed upon what action to take; half of us are for a battle, half against it. If we refuse to fight, I have little doubt that the result will be bitter dissension; our purpose will be shaken, and we shall submit to Persia. But if we fight before the rot can show itself in any of us, then, if God gives us fair play, we can not only fight but win. Yours is the decision; all hangs upon you; vote on my side, and our country will be free – yes, and the first city of Greece. But if you support those who have voted against fighting, that happiness will be denied you – you will get the opposite.’

Herodotus 6.109.3-6, trans. de Sélincourt

And Callimachus is won over, and votes for Miltiades.

The first words recall those of Dionysius of Miletus earlier in the book, with their specific Homeric echo:

ἐπὶξυροῦγὰρἀκμῆςἔχεταιἡμῖντὰπρήγματα, ἄνδρες῎Ιωνες, ἢεἶναιἐλευθέροισιἢδούλοισι, καὶτούτοισιὡςδρηπέτῃσι.

Matters are now on a razor’s edge for us, men of Ionia, whether to be free or slave, and runaway slaves at that.

6.11.2

And that had not ended well. It looks forward too, to the very similar ̓Ενσοὶ … beginning of Themistocles to Eurybiades before Salamis:22 ‘It is now in your hands to save Greece, if you do what I say …’ (8.60α) – again represented as a ‘to fight or not to fight’ decision, so the one battle presages the other. The phrasing may in its turn be echoed on the Persian side at 8.118.3, when the storm-tossed Xerxes calls upon his noble ship-board companions: ‘It is now in your hands – my safety’. And they all dutifully jump overboard. That is what Persian kingship is like; this is what Greek decision-making is like, with a sequence of life-and-death decisions, or rather something that matters more than life-and-death (which is what the original Homeric ‘razor’s edge’ model was about), for this is about freedom or slavery. The sad fate of the first of those sequences, with the collapse of the Ionian Revolt because the participants were not willing to show the proper resolve, only goes to underline what is at stake each time, and how at Marathon and at Salamis, too, things could so easily have gone differently.

‘To leave behind you for all future generations a memory more glorious than even Harmodius and Aristogeiton left …’: a ‘memory’, or rather a ‘memorial’, μνημόσυνον, an equivalent of the material memorials that were going to be dotted around the plain of Marathon in some profusion.23 That echoes Herodotus’ proem, with its project of preserving the κλέος of the great doings of the past and preventing them from being ‘wiped out’ by time – ἐξίτηλα, with its figuring of a parallel with a monumental inscription that becomes ‘faded’ or ‘eroded’. There will be further echoes of the proem before Thermopylae: the great κλέος that awaits Leonidas if he fights, so that the εὐδαιμονίη of Sparta would not be ‘wiped out’ (ἐξαλείφω, 7.220.2).24 This is what Herodotus’ work is for, as the proem makes clear, preserving the memory of deeds like this. And that is a very Homeric thought too, the everlasting κλέος – ἐςτὸνἅπανταἀνθρώπωνβίον here – for which heroes are fighting, to become (as Helen puts it, Il. 6.357-58) the objects of song for future generations. That was the κλέος that Homer’s song would itself give, and now Herodotus’ prose preserves the memory for which his heroes contend.

The other thing for which they are fighting is freedom. We could all write the sort of freedom-rhetoric that we would here expect Miltiades to be using, at least now that the decision has been streamlined into the simple to-fight-or-not-to-fight antithesis. We have become used to the inspiring power of freedom since Book 5, with the importance of their newly-won ἰσηγορίη in inspiring the Athenians now that they are all ‘fighting for themselves’ rather than for their tyrant masters (5.78);25 Dionysius of Phocaea had then produced a stirring negative equivalent when he spoke of the horror of being treated like runaway slaves (6.11). To modern tastes it is jarring that Miltiades now dwells so much on Athenian power: ‘this city of ours may well grow to pre-eminence amongst all the cities of Greece … our country will be free – yes, and the first city of Greece’; but probably that is just a matter of our modern sensibilities. We should just accept that freedom implied a continuum of self-assertion, as one first cast off the limitations on one’s own freedom imposed by an external master and then went on to dominate others and limit their freedom – a blurring, to use the favourite modern distinction, from ‘freedom from’ into ‘freedom to’. That continuum is already seen in 5.78, with the Athenians no better than their neighbours under the tyranny but becoming μακρῷπρῶτοιas soon as they are free. But the phrasing certainly gives a heavy hint of what is going to come next, after the Histories have finished – that process by which Athens will indeed become a domineering city in those ‘battles for the supremacy’ of 6.98.2 (above, p. 26), perhaps even become the new Persia and the ‘tyrant city’ of Thucydides’ rhetoric, though hints of that are louder as the last few books unfold.

The more immediate reasons for fighting are interesting too. There are no fine words in funeral-speech vein about Athens as the champions of Greece who set an example to others; none about the confidence to be had in autochthons fighting for their own land; no expression of trust that the gods are on their side (as there will be at 8.143.2): θεῶντὰἴσανεμόντων, that is all – the gods dispensing things equally. Even that has an air of the conditional about it, as in de Sélincourt’s translation, ‘if God gives us fair play’. There may well be gods around,26 but that is not the way Miltiades is thinking or talking. There is no ‘we will never surrender’: that sort of finest-hour rhetoric too is left for the end of Book 8, where its interpretation is anything but straightforward. The argument now is simply that there is too great a risk of stasis, and that any sort of delay may shake the Athenian resolve so that they may Medize. ‘Something rotten’ may set in, something σαθρόν, and Stein, How and Wells, and Nenci may be right in sensing nautical jargon here for this rotting ‘ship of state’.27 The argument makes sense.28 After all, we have seen enough states already decide that there could be worse things in the world than accepting Persian domination, and indeed those worse things had just been made very clear indeed, with the burning and enslavement of Eretria. When so many other states were Medizing, why should Athens not put up with a restored Hippias, especially as he was already pretty long in whatever teeth he had left? We should not forget that Herodotus himself described the decision of Ionian cities not to Medize as ἀγνωμοσύνη at 6.10, a word which commentators and translators dance around,29 but we cannot get away from it: when so many states were going over, a refusal to Medize was folly – glorious, wonderful folly.

Still, the argument is not very glorious, even if the upshot is. It is certainly a different world from that of the Iliad. There is no hint here of the fine words of Odysseus at Iliad 11.407-10, for instance, though admittedly that is not the only attitude to flight-or-fight in the Iliad; there is certainly nothing so uplifting as Sarpedon’s classic speech at Iliad 12.310-27. But it introduces a theme that is going to be strong in the next two books. Remember why Athens is the saviour of Greece at 7.139: no beacon-of-freedom rhetoric on the city as an inspiration to others, and it is nothing – perhaps pointedly – to do with what they did in 490. They just did not run away or Medize in 480 when so many other cities did. Remember too what weighs with Themistocles before Salamis: not the tactical arguments for fighting in the narrows – that is what he says in open council, because he cannot be frank in the presence of representatives of the other cities. But the way Mnesiphilus convinced Themistocles, and in his turn Themistocles convinced Eurybiades, was by stressing that if they withdrew to the Peloponnese too many of those other cities would ‘run away’, διαδρήσονται (8.60.1, cf. 8.57). The famous δρόμῳ advance of the Greeks at Marathon – ‘running’ into battle (6.112.2)30 – is so close to presaging a very different sort of ‘running’ later on. It could so easily have happened that way, and everyone knew it; this could indeed have been the Iliad over again, with the height of glory and the firing of the ships starting the movement that led to total disaster. What eventually persuaded the Greeks to fight at Salamis was Themistocles’ threat that the Athenians would sail away to Siris and leave the rest of the Greeks to their fate (8.62.2); what persuaded Xerxes to fight was Sicinnus’ message (8.75.2), which in its blend of truth and falsity had the news that the Greeks were thinking of running away (δρησμόν) and that Themistocles was really on the Persian side. All these claims were effective precisely because they were wholly plausible.

So we are left with a final paradox of freedom, as Herodotus presents it. The positive aspects, that inspirational aspect that was initially so stressed at 5.78, are not forgotten; perhaps indeed they are taken for granted.31 But there are also negative aspects to that individualism, with everyone acting for themselves in the way that 5.78 proclaimed. There is the perpetual danger that states may be torn apart by stasis as everyone pursues their own interests and vendettas, and that the self-interest of particular cities may fragment an alliance. The biggest paradox is that, at these crucial moments, it is the worst aspects of freedom, not the best, that prove the key to Greece’s triumph: it is the fear of Miltiades that stasis may overtake them that drives Athens to fight and win at Marathon; it is the fear of Themistocles that the alliance may break up that brings on the battle of Salamis; it is the inter-city factionalism and self-interested scheming that had in the past led Sparta to tell Plataea to turn to Athens (108.3) and would later generate the war between Athens and Aegina that proved the ‘salvation of Greece’ (7.144.1).

So downsides of freedom turn out to have very definite upsides; but downsides they remain, and the hints of the future suggest how the glories of 490 and 480 could turn very sour. Perhaps the very name of Plataea suggested as much, as I mentioned earlier,32 if one thought beyond 479 and down to 427 and that ‘battling for the supremacy’ (p. 26); in any case, the emphasis there on the Sparta-Thebes-Athens triangle would not have suggested any happy-ever-after feeling of Greek harmony. Nor would the jealousies and factionalism that we can already see in Athens, as we note that the real θῶμα Herodotus finds in the Alcmaeonid sequence (6.121.1) – another echo of the proem – is not that a treacherous shield should have been raised, but that people should have thought it to be the doing of the Alcmaeonids. Even with the Alcmaeonids themselves, a close reading of the next few chapters also makes us understand why people did suspect them, even if they were wrong: the shifting and enigmatic texture of their relations with the Peisistratids belies the easy initial statement that they were simply tyrant-haters throughout.33 Suspicions were natural; the great men of Athens really could get above themselves, in ways that carry that tinge of tyranny. Miltiades’ fate at the end of the book underlines the point, and the deft insertion of the reference to Pericles’ birth makes sure that the later perspective is not forgotten here either (131). Pericles would be a ‘lion’, indeed, with all the ambivalence that that figure suggests.

This, then, is the world of the polis, so very different from the Iliad; and the very modern day, the time of the Pentekontaetia and the Peloponnesian War, was different again, with more of the downside and not much upside. Yet heroism was still possible, and the events of Marathon proved it – but heroism with a difference. It was now a matter of finding counterparts, not unlike the way that a little later in the book Miltiades’ promise of ‘a place where they would easily find gold in abundance’ (χώρηντοιαύτηνδήτινα … ὅθενχρυσὸνεὐπετέωςἄφθονονοἴσονται: 132) is a latter-day counterpart of the tale of Alcmaeon that has preceded (125); not unlike, indeed, the way that the contests for Agariste’s hand (128-29) can be seen as a more modern counterpart of the chariot-racing contest won by Pelops for the hand of Hippodamia, this time with a clash between father and potential son-in-law that is lighter and less threatening.34 Winning eternal fame has changed, too, and is not a matter of heroic monomachies any more.35 The modern heroism requires instead an acknowledgement of the realities of the world, with all its jealousies and tensions and treacheries, and the insight and the rhetoric to exploit those in a style of leadership that offered something new.

Courage, of course, mattered too, with a readiness to face death and accept it for one’s city, not just for eternal fame; this was something that was already true in Hector’s Troy. The modern good death is described in ways that are all the more moving for their simplicity, again perhaps with a hint of monumental memorials. Callimachus died ‘having behaved as a good man’ (ἀνὴργενόμενοςἀγαθός: 114); Epizelus is blinded when similarly ‘behaving as a good man’ (ἄνδραγινόμενονἀγαθόν: 117.2).36 The Athenians fought ἀξίωςλόγου (112.2), just as the Spartans would at Thermopylae (7.211.3) – worthy of note, worthy of being talked about, worthy of Herodotus’ own λόγος as it grants them that eternal, epic memorial, and worthy of being talked about still, two and a half millennia later.

Endnotes

- Thus E. Vanderpool, ‘A monument to the battle of Marathon’, Hesp. 35 (1966) 93-106 at 105, accepted by E. B. Harrison, ‘The south frieze of the Nike temple and the Marathon painting in the Painted Stoa’, AJArch 76 (1972) 353-78, at 359 and 365-66, and by many since. Pliny, NH 35.57, Luc. Jup. Trag. 32, and Aelian NA 7.38 confirm that the painting included Cynegirus, and the extravagant phrase of Himerius 59 (10).2, ‘and the other man grasping and sinking the Persian fleet’ (τὸνδὲἄλλονδιὰχειρῶντὸνΠερσῶνστόλονβαπτίζοντα), confirms that someone, presumably Cynegirus, was shown in action by the ships.

- For the topographical significance of the marsh for a reconstruction of the battle see Rhodes in this volume. On the marsh in the Stoa Poikile, Vanderpool, ‘Monument’ (n. 1 above) 105-06; Harrison, ‘The south frieze’ (n. 1 above) 365; and now P. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (New Haven and London 2010) 114-17, 158-59 (thinking that Pausanias confused marsh and sea, as already argued by V. Massara, ‘Herodotos’ account of the battle of Marathon and the picture in the Stoa Poikile’, AC 47 [1978] 458-75, at 471-73). Topographical discussions: see esp. W. K. Pritchett, ‘Marathon’, Univ. Cal. Publ. Class. Ant. 4.2 (1960) 137-75, at 152-56; A. R. Burn, Persia and the Greeks (2nd edn 1984; 1st edn was 1962) 245 and 251; N. G. L. Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle of Marathon’, JHS 88 (1968) 13-57, at 18-24; J. A. G. van der Veer, ‘The battle of Marathon: a topographical survey’, Mnem. 35 (1982) 290-321 at 297-98 and 306; J. A. S. Evans, ‘Herodotus and the battle of Marathon’, Hist. 42 (1993) 279-307, at 291-93 and 302; J. F. Lazenby, The defence of Greece (Warminster 1993) 65 and 70-72.

- Just as other touches prefigure both Thermopylae and Salamis: below, pp. 29, 32, 34.

- 6.48.2-49.1, 94.1; cf. the Persian demands ten years later (7.32), to which once again many agreed (7.131-32, 8.46.4, cf. 7.163.2). Notice too the μή at 6.94.1, Darius’ wish to καταστρέφεσθαιτῆς ̔Ελλάδοςτοὺςμὴδόνταςαὐτῷγῆντεκαὶὕδωρ. Stein remarked that οὐ would be ‘richtiger’, but the μή correctly conveys ‘whichever Greek states shall not have given earth and water’. They have a choice, and many exercised it in favour of submission.

- Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 2 above) 42-43, interestingly suggests that the Athenian submission was never in fact repudiated, and it was this that prompted the Corinthian reluctance to fight Athens in (?)506 (5.75.1). S. West, ‘A diplomatic fiasco: the first Athenian embassy to Sardis (Hdt. 5, 73)’, RhM 154 (2011), 9-21, prefers to think that the Athenian ambassadors only said that their city would give earth and water, and the actual gift of the physical emblems would only have been made once they, together with Persian representatives, had returned to Athens; in that case the real submission would never have been made.

- Cf. C. B. R. Pelling, ‘Thucydides’ Archidamus and Herodotus’ Artabanus’, in Georgica. Greek studies in honour of George Cawkwell, ed. M. A. Flower and M. Toher, BICS Supp. 58 (London 1991) 120-42,at 136-38.

- H. Y. McCulloch, ‘Herodotus, Marathon, and Athens’, SO 57 (1982) 35-55, at 44.

- A. R. Burn, Persia and the Greeks (London 1962) 250.

- This is weakened unduly in Waterfield’s translation, ‘began to take over the ships’.

- Contrast A. D. Fitton Brown, ‘Notes on Herodotus and Thucydides’, Hermes 86 (1958) 379-82, at 379, who misses this ‘keeping a firm grasp’ point of the present tense. The sense he finds is ‘that Cynegirus had his hand cut off while engaged in seizing the sterns (cf. ἐπελαμβάνοντοτῶννεῶν above); we may surmise that he was the leading spirit and looking round to see how the others were getting on.’

- R. Janko, The Iliad: a commentary iv (Cambridge 1992) 306.

- Apollonius Rhodius 1.1089 and Lycophron, Alexandra 26 and 295. Its etymology was evidently unclear too, though φλάω was readily taken as a metathesis or corruption of θλάω. It ought to mean ‘uncrushable’, suggesting that the poops were somehow strengthened. This may be right, though it does not look as if any ancient writer thought of that. A favourite guess in the Etymologica was that it was euphemistic, an a contrario formation because they were so easily crushable or broken off: that does not sound very plausible. Polemon 2.simply has Cynegirus grasping τοῦἀκροστολίου, ‘the terminal ornament’ (LSJ), i.e., the figurehead at the prow or the stern-post at the rear; Paulus Silentiarius Anth. Gr. 16.118 has γαμψοῖοκορύμβου (‘the curved upper point’ of prow or stern, cf. Iliad 9.241). (The two passages are quoted in the useful collection of testimonia at Harrison, ‘The south frieze’ (n. 1 above) 374-75.) Both are presumably interpretations of ἄφλαστον, though it was also possible to distinguish the ἀκροστόλιον or κόρυμβον at the prow from the ἄφλαστον at the stern (Eust. iii.790.11–14, Etym. Magn. pp. 53 and 177 K., Etym. Gud. k 351). The word was clearly a pedant’s delight.

- L. Scott, Historical commentary on Herodotus Book 6 (Mnem. Supp. 268, 2005) 391; Evans, ‘Herodotus and the battle of Marathon’ (n. 2 above) 287, cf. 293, ‘the Homeric struggle at the ships’; McCulloch, ‘Herodotus, Marathon, and Athens’ (n. 7 above) 44. So also now Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 2 above) 158: like the use of κόπτω, the call for fire ‘lends an epic quality to the narrative’.

- J. R. Grant, ‘ἐκτοῦπαρατυχόντοςπυνθανόμενος’, Phoenix 23 (1969) 264-68, at 264.

- As D. Hennig thought, ‘Herodot. 6, 198: Athen und Plataiai’, Chiron 22 (1992) 13-24. The ‘back then’ was presumably in 519 BCE, for that seems to be the context to which Herodotus is referring back at 6.108: on this see Hornblower on Thuc. 3.68.5.

- Cf. also K. R. Walters, ‘“We fought alone at Marathon”: historical falsification in the Attic funeral oration’, RhM 124 (1981) 206-11.

- And, for that matter, in what Xerxes says at 7.10b.2, but that is more understandable. It is the Athenians that loom largest in his mind.

- Cf. N. Whatley, ‘On the possibility of reconstructing Marathon and other ancient battles’, JHS 84 (1964) 119-39, at 131: ‘The importance of Marathon seems in many ways to have been exaggerated by most ancient writers except Herodotus, and even Herodotus shares in the exaggeration in Book ix, chapter 27.’ But at 9.27 Herodotus may well be wryly exposing the Athenians’ exaggeration, not sharing in it. ‘Many patriotic citizens of Athens must have read the Herodotean account of Marathon without pleasure’: Evans, ‘Herodotus and the battle of Marathon’ (n. 2 above) 307, cf. 279-81.

- ‘Simonides proposes to do for the Persian War what Homer did for the Trojan War’, P. J. Parsons, ‘“These fragments we have shored against our ruin”’, in The new Simonides, ed. D. Boedeker and D. Sider (Oxford 2001) 55-64, at 57; interesting comments also in that volume by I. Rutherford (38), D. Obbink (71-72), D. Boedeker (124-26 and 153-63), P. J. Shaw (165, 180-01), J. S. Clay (182-84), and A. Barchiesi (257).

- ‘Herodotus and Homer’, in Epic interactions, ed. M. J. Clarke, B. G. F. Currie, and R. O. A. M. Lyne (Oxford 2006) 75-104.

- Including the constitutional position of the polemarch and how stratēgoi were elected. See Rhodes pp. 16-17 above.

- As Evans, ‘Herodotus and the battle of Marathon’ (n. 2 above) 284, observed.

- And also of Callimachus’ monument on the Acropolis (IG i3 784 = ML 18 = Fornara 49). There μν[έμεν, μν[μαuel sim. are read, when other restorations differ, by B. B. Shefton, ‘The dedication of Callimachus (IG I2 609)’, BSA 45 (1950) 145-64, at 153-58, by E. B. Harrison, ‘The victory of Kallimachos’, GRBS 12 (1971) 5-24, at 19, and by O. Hansen, ‘The memorial of Kallimachus reconsidered’, Hermes 96 (1988) 482-83.

- Pelling, ‘Herodotus and Homer’ (n. 20 above) 95.

- That passage is echoed too in the narrative of the Ionian Revolt: for all the unsatisfactory nature of the Ionian resistance there, at least the Chians conspicuously do not ‘play the coward’ (ἐθελοκακέειν, 6.15.1), just as the Athenians stopped their cowardice (ἐθελοκακέειν) at 5.78.

- As in the epiphany of Pan to Pheidippides (105.2-3) and the further hint of an epiphany with the monstrous figure who looms over Epizelus (117); and it is surely not coincidence that the action moves from one sacred area of Heracles to another (108.1, 116.1). Then Datis’ mysterious dream at Myconos (118) suggests some Iliad-like wrath of Apollo, despite all the ostentatious propriety of ch. 97. For the role of the divine at Marathon see further Gartziou-Tati in this volume.

- Stein also commented on the immediately preceding ἐμπεσοῦσαν: ‘wie ein Wogenschwall auf ein Schiff’, comparing 3.81.2.

- What may not make sense is, in that case, the delay of several days in joining battle: if there was a danger of a failure of resolve, the best thing would be to fight it out straight away. Cf. Whatley, ‘On the possibility of reconstructing Marathon and other ancient battles’ (n. 18 above) 136-37: perhaps Whatley’s own well-informed comments, beginning ‘I can only reply that there has been delay before half the battles in history…’, are enough. This problem is evidently affected by the bigger question whether it was Miltiades’ rather than the Persians’ decision that brought on the battle when it did. For the delay see further Rhodes p. 4 above.

- How and Wells talk of ‘obstinacy’, Waterfield has ‘remained committed to their chosen course’, de Sélincourt ‘all of them firmly refused’, Nenci ‘stoltezza’, Shuckburgh ‘obstinate defiance’, Rawlinson ‘staunch’, Godley ‘stubborn’. Scott, Historical commentary (n. 13 above) now approves Mandilaras’ ‘categorically rejected’. Legrand’s ‘manque de jugement’ is better; so is Stein’s remark on 5.83.1, ‘ἀγνωμοσύνη bezeichnet den Mangel an ruhiger, besonnener Überlegung …’. Such an acknowledgement of folly does not prevent Herodotus from applauding those who stayed firm during the fighting (14-15): this simply shows his capacity to adopt multiple perspectives when actions or events are morally complex, as in his remark that Aristagoras ‘ought not to have spoken the truth’ to Cleomenes at 5.50.3.

- On which see now esp. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 2 above) 143-52, with thought-provoking modern parallels.

- We are going to hear enough of those positive aspects, too, in the next few books, strikingly often in Spartan mouths. There are the fine words of Demaratus to Xerxes at 7.101-04, even if more of his emphasis there falls on νόμος than on freedom; then the Spartan ambassadors tell the uncomprehending Persians that if they knew freedom the way that the Greeks know freedom, they would fight for it not just with staves but with axes (7.135.3).

- Above, pp. 26-27.

- Cf. J. L. Moles in Brill’s companion to Herodotus, ed. E. J. Bakker, I. J. F. de Jong, and H. van Wees (Leiden 2002) 40-42 and now esp. E. Baragwanath, Motivation and narrative in Herodotus (Oxford 2008) 28-32. Those shifting relations are already clear at 102.2-3, and cf. esp. 61.60-61. For Alcmaeonid collaboration with the tyranny cf. Rhodes pp. 17-18 above.

- Mentions of the Olympic games cluster around this context (122.1, 126.2, 127.3), and Olympic victories ran in Miltiades’ family too (36.1, 103): Pelops, so closely associated with Olympia and the games, might easily come to mind. L. Bertelli, ‘Hecataeus: from genealogy to historiography’, in The historian’s craft in the age of Herodotus, ed. N. Luraghi (Oxford 2001) 67-94, at 75, prefers to see a link with the competition among Helen’s suitors (Hes. Catalogue of women frgs. 200-204 MW), suggesting that oral tradition had developed the myth as ‘a reflection of another famous wedding, that of Agariste at Sicyon’ (6.128-29); but there too it may be better to see it the other way round, with Herodotus offering a modern counterpart of the mythical story. The suitors of the Odyssey are also not too far away.

- Notice that the previous sequence does have a monomachy (92.3) between an Aeginetan stratēgosand a series of Athenians; that has a feeling of already belonging in the past. The future belongs to the naval exchange that immediately follows (93), with the Aeginetans for the moment the skilful ones.

- Such ἀνὴρἀγαθός locutions are particularly frequent when people show themselves ‘good men’ in fighting, and often dying, for freedom: Stein lists also 5.2.1, 6.14.1, 7.224.1 (Leonidas), 9.17.4, and 9.75.1 (but also 7.53.1 on the Persian side).

Contribution (23-34) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.