Examining radically altered intellectual landscape primarily through two manuscripts.

By Dr. Edward M. Schoolman

Associate Professor of History

University of Nevada, Reno

Introduction

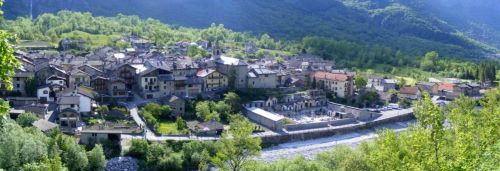

Nestled in a mountain valley on the southern side of the Alps, the Monastery of St. Peter at Novalesa played many roles throughout its history. It was an early outpost of aristocratic patronage, founded by a nobleman named Abbo of Provence in 726 as an expression of piety and to consolidate control over the Mount Cenis pass, an important route between Frankish Gaul and northern Italy.1 Its early history tied it to the communities north of the Alps far more than it did to those in the rest of Italy, until the first decade of the tenth century when the monks were forced to flee under the threat and eventual arrival of a Muslim raid. Following almost a century of exile, a new generation of monks returned to reclaim the site of the monastery and their history; while the reconstituted Novalesa thrived, it did so in a radically different time. And although it reclaimed aspects of its past, it would never regain its stature.

In considering its place between Frankish and Italian influence, regional and local patronage, and the evolution of monastic movements, the history of Novalesa presents a number of compelling questions. Given the history at the site and its two periods of occupation, how can we trace the informal personal, intellectual, and institutional networks to which Novalesa belonged? How did these networks change for the monastic community during the two discrete phases at the site? And finally, how did the century-long processes of rebuilding Novalesa’s library and the reclaiming of its history reframe its position?

While these types of questions are difficult to answer for most monastic institutions, they are especially complex for No-valesa, given that its abandonment at the beginning of the tenth century resulted in the loss of nearly all of its manuscripts and charters, some of which were later recovered, others forged, and some lost entirely. Following the reestablishment of the monastic community in the eleventh century, the texts and manuscripts composed served as witnesses of the effort to recapture its past and affirm its present status, and offer a glimpse of the links shared between its patrons and abbots, and most importantly its connections to other institutions through shared texts. These sources illustrate Novalesa’s historical and imagined reliance on Frankish patronage and ties to other monasteries beyond the Alps, from Cluny to Reichenau, as well as how the re-instituted community utilized its memory and links to rebuild its library and reconstruct its past.

These diverse facets reveal a monastery that began its existence in the eighth century as an outpost of Carolingian monasticism and patronage and that retained personal ties to Gaul, notably Provence. After its exile from the Novalesa site in 906, the community retained some knowledge of its history despite the loss of institutional memory and the papers and charters that protected it. In the eleventh century, the exiled community returned to the site of Novalesa, and began to collect texts to build a new library while relying on its connections to other monasteries. In addition to navigating its new position within local Italian networks, members of this latter community would produce new texts that recreated its lost history.

Given the nature of the surviving sources from Novalesa, this study aims to be exploratory rather than exhaustive, seeking the contours of Novalesa’s place within a radically altered intellectual landscape primarily through two manuscripts composed following its reestablishment: the Chronicle of Novalesa and a miscellany now at the Newberry Library in Chicago. The following sections describe the various ways to imagine monastic networks, the history of Novalesa and certain manuscripts produced following its reestablishment, the history of the abbots and their personal and geographic links, and projections of the monastery’s status in memory and its role in the eleventh century.

Recovering Novalesa’s Monastic Links

As the primary engines of manuscript production in the early Middle Ages, monasteries held a privileged position in the transfer of knowledge, maintained through the activities of the scriptoria in particular and monastic schools. Because monasteries had other responsibilities, such as the care and spiritual health of the monks and their supporters, and served as the objects of elite patronage, these various facets often became intertwined. Given these traits, there is no consensus as to what makes a monastic network, which could be informal and driven by personal as well as institutional connections, on the one hand, or part of more formal arrangements through shared patronage or extended monastic communities, on the other. In considering their role in education and the production of texts for that purpose, monasteries were often central nodes in larger educational networks, especially under the Carolingians.2 Beyond their educational structures, individual monasteries also formed the locus of “horizontal learning” in informal pathways.3 Examples of important imperially sponsored monastic houses, such as Farfa, underscore the continuities and mutual benefits of monastic patronage networks.4 Both within and beyond the confines of monastic walls, monastic spiritual and emotional networks bound together monks and nuns into families.5 Finally, with the rise of Cluny, monastic networks could also be formal agreements of support. Even early in the tenth century, Cluny had become part of a Klosterverband and later would become the mother-house to a network of smaller monasteries and reformer to even more.6

In this study, I am most concerned with the ephemera of networks in which only individual links remain visible: the transmission of texts and manuscripts, the relationships between patrons and monasteries, and the careers of abbots and monks. Together they help to illuminate the position of the historical “Novalesas”: the Carolingian monastery in northern Italy through 906, this early monastery as it was imagined during the period of exile and resettlement, and the renewed Italian monastery of the eleventh century.

Although many manuscripts survive from the reconstituted monastery of Novalesa, this chapter will focus on two with clear provenance and a record of critical study. The foundational scholarship on the majority of Novalesa’s medieval manuscripts and history was undertaken by Carlo Cipolla, who in the last decades of the nineteenth century consulted a significant portion of the manuscripts and texts associated with the monastery. His scholarship incorporated his research and updated editions of texts specific to Novalesa in the two-volume Monumenta novaliciensia vetustiora, among others.7

The ‘Chronicle of Novalesa’

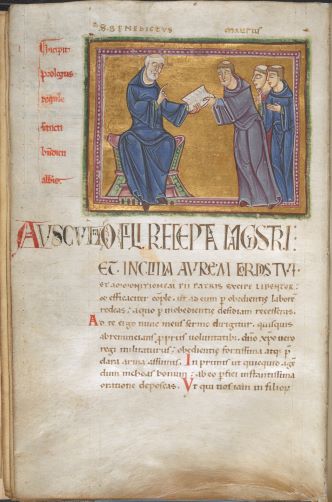

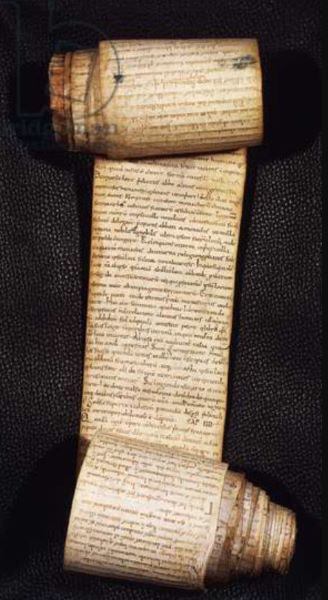

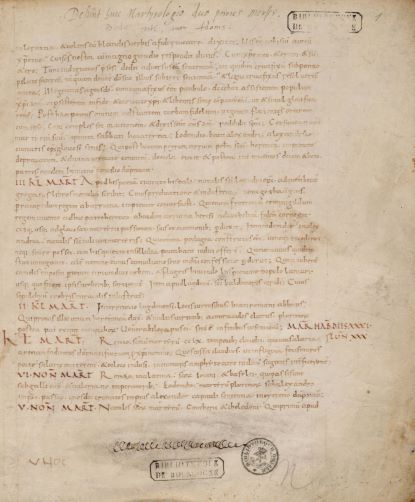

The Chronicle survives as a single medieval rotolus written around 1050 and covers the period from the monastery’s mythical establishment through 1014. The manuscript today is imperfect, as the first sections were damaged and, along with others, only preserved in an eighteenth-century transcription. Known as the Chronicon Novaliciense, the work consists of a five-part “history” of the monastery from its initial mythical establishment to its refoundation by the abbot Gezo, and an “appendix” of brief notices and anecdotes designed to be later inserted into the main text.

The Chronicle of Novalesa was composed in inelegant Latin, with clear historical embellishments, problematic chronology, and incoherent organization. The chapter titles listed at the beginning of each book inconsistently describe the chapter’s content. The text has often been seen as a creation of its age, using the cultural resources available to monks lacking refined literary skills yet attempting to bring together the surviving history of their institution. Due to its apparent disorganization, it may also have been a work-in-progress or a “scratch pad” for a more formal record. The value of the text has centered on its accounts of Novalesa’s connections to the most important figures of the Carolingian age, including Charlemagne and his successors, and its reliance on the history of the ninth-century poem about the life of Walter of Aquitaine, the Waltharius.

The text received its first published edition by Celestinus Combetti in 1843; another edition was made for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) by Lodovico Bethmann, published in the seventh volume of the Scriptores series in 1846.8 A fully annotated edition of the text appears in the second volume of Carlo Cipolla’s Monumenta novaliciensia, with a detailed introduction on the history of the manuscript’s publication up to that point. More recently, the Chronicle received an Italian translation with an edition by Gian Carlo Alessio in 1982 and a complete English translation in 2017 in the dissertation of Elizabeth Artemis Clark.9 Several scholars, most notably Patrick Geary and Uwe Ludwig, have scrutinized stories about the monastery’s various destructions, reconstructions, and the patronage of royal and aristocratic families, many of which are fictional but serve to construct a plausible past for the monks.10

The ‘Novalesa Miscellany’

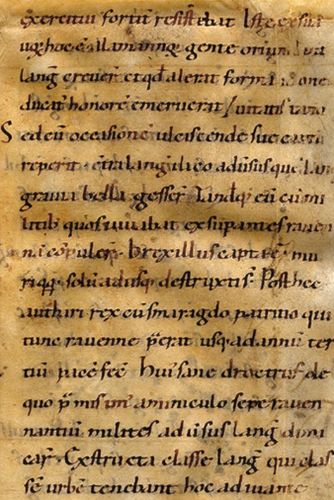

The manuscript of a miscellany from Novalesa, now housed at the Newberry Library in Chicago, was formed from two distinct eleventh-century manuscripts bound together later in the Middle Ages.11 The better-known second half includes the first two books of Paul the Deacon’s Historia Langobardorum with a spurious description of the oblation of Charlemagne’s illegitimate son Hugo to the monastery of Novalesa (which appears in the Chronicle).12 The first half, composed of 107 folios, contains a true miscellany created for a monastic audience. The main portion contains sixty-eight folios of the Expositio missae of Amalarius of Metz, as well as sermons, saints’ lives, penitential texts, epigrams, and a “glossary” of Greek terms.

Other notable works included were a letter on the Hungarians attributed to Remigius of Auxerre, a short poem on the double creation of life by Eugenius of Toledo, Quid sit ceroma, a tract once thought to have been authored by Lupus of Ferrières but now attributed to his student Heiric of Auxerre, and finally on the last folio a list of small donations made by the local laymen who supported the monastery. Despite their disparate origins, these texts collectively imply that the network from which Novalesa rebuilt its library (or portions of it) had nodes ranging from Cluny to Reichenau to Santa Maria in Ripoll, Catalonia.

Abbots in Monastic Networks

Overview

In trying to understand Novalesa’s place before and after its tenth-century exile, the abbots who served its community demonstrate patterns of connections that increasingly looked north-ward, reflecting their communities’ orientations. Three others with more conventional careers illustrate this northward-facing gaze, including its most famous abbot, Eldrad, who later became the monastery’s saint and spiritual patron. The careers of Eldrad and his predecessor, Frodoin, representing Novalesa’s first phase, and Gezo and Aldradus representing the second, appear to reveal the long-lasting pull of increasing intensity toward communities in the Frankish heartland, though this is a conclusion not without complications. The most significant uncertainty rests with the historically unreliable Chronicle of Novalesa, which serves as our primary source for the abbacies of Frodoin, Eldrad, and Gezo. In the cases of these three abbots as recorded in the Chronicle, what appears are the projection of an idealized past and aspirations of the reconstituted monastery. From these, we find reflections of the actual institutional networks of the abbots through their personal connections to locations and people.

Frodoin

Our knowledge about the career and network of Frodoin is based both on the Chronicle of Novalesa and on charters, some original and others preserved in later copies. The charters include the issuance of two immunities to the monastery in 773 and 779 by Charlemagne and are useful because they document the most important events in Frodoin’s career as abbot.13 Along with the Chronicle, these sources formed the basis for a forged charter reaffirming early grants under Pippin and the monastery’s first patron, Abbo, as well as the spurious oblation of Charlemagne’s son Hugo in 774. Given these details, the forgery was likely a product of the monastic reconstitution in the eleventh century, as the details also appear in the Chronicle as well as in a description of the forged renewal requested by Frodoin.14

While the immunities reflect the standing of both Frodoin and Novalesa at its height, including multiple visits by Charlemagne as he traveled between Gaul and Italy, the Chronicle suggests that Frodoin himself had a strong and visible connection to Frankish elite society. In book 3, he is described as one of the sons of Magfred, presumably a noble Frank who, like his predecessor as abbot, Asinarius, “was of the Frankish race, and was of the greatest renown among the nobility of the Franks. His father gave to him many estates of land and entrusted him to the monastic community for his education.”15 The Chronicle places this event during the reign of Pippin.

Following the deaths of Asinarius and his immediate successor, Witgar, the Chronicle describes the unanimous support for and election of Frodoin, along with his charismatic gifts. Perhaps most importantly (at least for the eleventh-century author), the abbot had overseen the continued growth and development of its resources. This proved useful in an anecdote when Charlemagne’s army settled in Novalesa on its way to Italy (presumably in 773), and the monks’ provisions were consumed at royal meals. This occurred because “the monastery in those days was extremely wealthy and most rich in resources and had been well-stocked by the most holy father,” that is, Frodoin.16 This generosity was rewarded, as later Charlemagne granted “a huge estate called Gabiana, where there were a thousand manses with their dependencies” to the monastery, which he provided specifically “to Novalesa because of his reverence for the abbot.”17

This Gabiana appears in the forged charter of 774, as does the oblation of Hugo, which is mentioned on the return of Charlemagne following his defeat of the Lombard king Desiderius. With the oblation came more property and gifts, along with rel-ics belonging to Cosmas and Damian (connecting the monastery, at least hagiographically, to Rome) and those of Walaric (who appears as Walericus in the text and known more widely as Valery), the founder of the abbey of Leuconay. More reliable evidence from the mid-eleventh-century Vita Walarici abbatis Leuconaensis posits a different final location for Walaric’s relic: that Charlemagne gave them to Corbie, but that in the tenth century they were translated to Saint-Bertin, and to Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.18 This translation would have been widely known, and the account of the Chronicle perhaps attempts to position Novalesa among these royally supported monasteries in Gaul. Indeed, the majority of the career of Frodoin as described in the Chronicle relates to the pull of, and relationship with, the Carolingians and Gaul. In light of the situation of the monastery in the eleventh century, the imagined eighth century must have seemed a past worthy of their ambition.

Eldrad

The history of Eldrad contains as much fiction as does that of Frodoin, complicated by the fact that he was venerated as a saint whose vita emanated from the monastic community of Novalesa before, during, and after the exile of 906 in various forms.19 Like with Frodoin, the main biographical element highlighted in all of the vitae, such as the impartially preserved vita rythmica and the historical account preserved in one of Novalesa’s Martyrologium Adonis, were his origins in Gaul and his elevation by an unnamed Carolingian monarch.20

The historical account in the large martyrologium in Berlin (Hamilton 4), written as an addition to the main text, presents the geographic context of Eldrad:

In the monastery of Novalesa: The deposition of the blessed abbot Eldrad. This distinguished man was a native of the Gallic Provence […]. He finally came to Novalesa, where he led a celibate life and he was made the worthiest father of nearly 500 monks by the grace of his king.21

According to the Chronicle, Eldrad’s tenure as abbot began with the death of his predecessor, Hugo (considered by the author to be the illegitimate son of Charlemagne). While the Chronicle describes the final years of Hugo’s career as having been spent building monastic communities “under the dominion of Novalesa” in Francia, as well as a gift of a monastery dedicated to Medard in Soisson, the focus of Eldrad from the surviving titles of the chapters was less with the building of Novalesa’s physical holdings than its intellectual ones.22 Unfortunately, the activities are lost due to the fragmentary preservation of book 4 of the Chronicle, but the titles of the lost chapters indicate correspondence with Florus of Lyon, a prodigious writer working in the Lyon scriptorium, evidence of intellectual exchange in the service of the monastery.23

One example of this exchange survives in a letter from Florus to Eldrad that addresses Florus’s method of textual criticism and aptitude in editing a psalter that he received from and then returned to Eldrad.24 Although the earlier correspondence does not survive, the text of the letter suggests that Eldrad had obtained the services of Florus in an innovative venture to improve the language of the translations of the liturgically employed psalms. More so than the boastful and uncorroborated gifts and privileges that the monastery could obtain from the Carolingians, this letter alludes to a now-lost intellectual activity and exchange that served as one of the links within the monastery’s networks in the ninth century.

The intellectual activities taking place in Novalesa are further confirmed in a section of the Chronicle that makes references to the production of Novalesa’s own master of the scriptorium, Attepert, who like Florus used a unique hand, and served during the tenure of Frodoin in the generation before Eldrad. The Chronicle dedicated an entire chapter to his career:

This same Attepert was a monk and a priest in this oft-mentioned monastery, namely in the times of the dear Frodoin. He was a servant of this monastery, as greatly imbued with the knowledge of letters as he was an extremely swift scribe of correct writing. As a matter of fact, he himself copied many diverse and very large books at the monastery in his time. Therefore, whenever we find among the other books ones written in his calligraphic hand, we immediately recognize them.25

Although no extant manuscripts are known in his hand, this shaped both contemporary understanding of Novalesa’s importance and the reflection of the eleventh-century context of the Chronicle. Now visible only though its shadows, ninth-century Novalesa’s intellectual links to Carolingian Gaul must have been extensive given that a chapter was dedicated in its history to the copying activities in their own scriptorium.

Eldrad’s career left no other contemporary trace but for references in two problematic charters. The first is a mid-tenth-century forgery or interpolation that claims to record a royal endowment for 825 (the extant copy dates from the twelfth century), and one from 827 that also appears as a copy, although that has been described as more faithful to the original and was available to the compiler of the Chronicle. While Cipolla has discussed both at length, it is worth noting as a final coda to the career of Eldrad that the charters position the abbey within two different contexts, one imperial and one local.26

The 825 charter deals with the foundation of an almshouse at Moncenisio (the location of Novalesa) dedicated to Mary in fulfillment of a vow made by the Carolingian Lothar I (who was king of Italy at the time), and places the monastery of S. Pietro di Pagno under Novalesa’s control. In this case, Eldrad was engaged with some of the most powerful secular figures, perhaps those who were responsible for his elevation referred to in the last line of his entry in the martyrologium in Berlin mentioned above, with the outcome that the monastery strengthened its local holdings and regional position, as Pagno and Moncenisio are both located in the southwestern area of the Piedmont. Even if fictitious in part or whole, its mid-tenth-century context affirms how the community of Novalesa may have imagined this part of its past while in exile.

The charter from 827 encompassed some of the focus of the 825 charter with its geographic focus on the immediate areas around Novalesa, yet reflected a distinct framework of local elites. Rather than a granting of rights, this document was a notice of a judgment made in the presences of several vassals of Emperor Louis the Pious, and finally under the authority of the Count of Turin, Ratpert. The judgment recapitulates the complete dispute, which began as an accusation made by fourteen named men, described as commanentes (that is, manentes or coloni) of villa Auciatis, who claimed that Eldrad as the abbot of Novalesa had unjustly held them in servitude.27 The advocate for the monastery, Ghiseberto, denied their claim, arguing that they had been included with a gift of land from a certain Hunno; as a counterclaim the commanentes said that Dionisio, the father of Hunno, had granted them a cartola libertatis, freeing them from servile labor. This claim was refuted and the fourteen admitted that their document had been forged, with the result that they committed to continue to serve the villa.

Although there is no evidence that Eldrad took part in the two phases of the dispute, the first in Turin under Count Boso, and the second in Catenasco under Ratpert, the monastery’s insistence

on maintaining control over the peasants who worked its land reflects its economic and strategic priorities at the local level. The use of secular authority to enforce its claims suggests that Novalesa and its abbots had strong links to regional elites, not just the counts of Turin but also landholders like Hunno, although no other documents (copied, forged, or otherwise) help to elucidate the relationships. Yet like the links maintained through exchanged manuscripts to Florus of Lyon, this manifestation of authority via local connections ceased abruptly in 906 when the monks were forced to leave their community, resulting in the loss of the majority of their manuscripts and charters and significant portions of their institutional history.

Gezo

Gezo’s career was marked by two related events: his reclaiming the original site of Novalesa and his desire to move the community back. He belonged to the community that had evolved from those who had fled Novalesa and reestablished the monastery in Breme. The historical context of Gezo, who served as abbot from possibly as early as the 980s to after 1002, was radically different from his pre-exile predecessors. In the intervening century, not only had the monastery relocated twice, but the Carolingian dynasty dissolved completely, replaced by the Ottonians in Germany in 919 and the Capetians in Gaul in 987. The late Carolingian kingdom of Italy had suffered far greater instability than those regions, as Frankish claimants contended for the remnants of diminished royal authority, and at times an imperial title, beginning with Berengar I in 887.

During the tenure of Gezo, Italy had become a core holding for the Ottonians, and under the brief reign of Otto III, many monasteries whose fortunes had waned found renewed favor. Despite the establishment of stability in the kingdom following the arrival of the Ottonians in 951, the Novalese community at Breme suffered internal strife. The Chronicle presented an ill-defined attempt made by Arduin Glaber (count and later margrave of Turin) to dispossess the monastery of its independence or claim ownership of its territory.28 Through the intervention of an emperor Otto (likely Otto II), Gezo was able to restore the monastery’s privileges and have them reaffirmed.29 In another set piece in the Chronicle, Gezo faced the wrath of the margrave Guido (presumably the grandson of Arduin Glaber); Gezo was forced to leave, but in a vision he saw Saint Peter direct a demon to set upon Guido with sticks. Guido quickly fell into madness.30

It was with the tacit support of the Ottonians that Gezo began the project of rebuilding Novalesa, by sending a monk to ascertain the state of the ruins and to build a small chapel dedicated to St. Andrew on the site that had been “destroyed and had been nearly forgotten.”31 This began the process of rebuilding and even moving the community, one that is not clearly described in the Chronicle, but seems to have taken place in the decades following the first attempts at restoration. An anecdote in the appendix of the Chronicle describes a community of monks from Breme occupying the monastery in Novalesa, but without ecclesiastical support: “Then in modern times, the monks living there, deploring the devastation, beseeched the bishop of Ventimiglia to consecrate the ruined chapels, that is to say, those of Saint Michael and of Holy Mary Mother of God, and of Saint Salvator and of Saint Eldrad.”32

Beyond the support of the Ottonians, the Chronicle under-scored the monastery’s strained relationships with the lords of Turin and Leo of Vercelli, and described Gezo’s career in miracles among the monks and inhabitants of northern Italy. In one instance, a bishop of Alba named Fulcred gave Gezo relics of Frontian and Silvester because Fulcred had once been a monk, but other miracles were set in the territory of Pollentia, the passes of Mount Cenis, and the town of Camerletto on the backs of the river Dora, all locations within the immediate area of Turin or Novalesa.33 These regionally centered episodes are especially fitting given that Gezo himself belonged to this milieu rather than sharing the connections to Gaul that were dominant in the careers of the abbots of pre-exile Novalesa. Both his career and the continued importance of Novalesa within the region demonstrated the position of the monastery and its local links as they were interpreted by the established post-exile community that created the Chronicle.

Aldradus

While the accounts of Gezo’s career focus on the reestablishment of a community in Novalesa while contesting local authority and seeking the approval of imperial power, the career of Aldradus marks a renewed connection to Gaul. Although we only know small snippets about his career and life, the timing of his monastic career, from Vendôme to Cluny to Novalesa and finally to Chartres, also traces a new pattern for the intellectual position of Novalesa, this time in relation to the ascendant Cluny. In her authoritative study of Aldradus’s life, Giuliana Giai argues that he was the son of the Count of Nogent and his career began as a monk in Vendôme, ca. 1033.34 He is next noted in the extant records as a member of Cluny by 1048. Following a short stint as prior in the monastery of Peterlingen (which had been restored by the abbot Odilo of Cluny), Aldradus was abbot of Breme and Novalesa in 1060.

No record exists of his activities in Novalesa, but given his previous posts and connection to Odilo of Cluny, he likely carried forward not only the initiative of reform from Cluny but also sought to revive Novalesa’s own traditions in the post-exile period by memorializing its earlier history. For example, the oldest surviving frescos on the chapel of Eldrad were painted during Aldradus’s tenure and include him as a patron. The earliest prose vita of Eldrad may have appeared in this period as well, although what later circulated comes in the early twelfth century as the vita mentions the fall of Jerusalem to the crusaders.35 The success of Aldradus was not in the refurbishment of the church in Novalesa, but in his next assignment. According to the report on his career in Peter Damian’s biography of Odilo of Cluny, in 1069 Aldradus became the bishop of Chartres, a position he held until his death in 1075.36

The connections that Aldradus brought to Novalesa were critical to preserving its historical memory. Through the more substantial network of Cluny’s monasteries and reformed houses, Novalesa regained access to the same types of materials that it had lost in its exile and, more importantly, from many of the same institutions or their intellectual successors. The return to face Gaul — not just Burgundy and Provence — also served to help restore the importance of Novalesa’s history with the Carolingians, whose hagiography was continually revised.

Networks of the ‘Novalesa Miscellany’

This single manuscript, made up almost entirely of well-circulated texts and copied in the restored monastery, makes a unique witness to the intellectual connections and possible networks built by Novalesa during this period. Yet the construction of the Miscellany, the selection of texts it contains, and, ultimately, its violation of genre, connect it both to the world of the mid-eleventh century and that of the Carolingian age.

This particular manuscript has had an interesting afterlife. It was bound with the short section of the Historia Langobardorum in the late Middle Ages, and in this form the manuscript entered private hands following the first suppression of the monastery in 1785. It made its way to England and to the Phillipps collection; at the dissolution of that collection, the Newberry Library purchased the manuscript in 1936.37

While still part of the Phillipps collection, it came to the attention of Cipolla, who published the first full account of the manuscript’s content while making important observations about the miscellany’s formation as part of his studies on the material related to Novalesa’s medieval history. It was Cipolla who fully recognized the importance of the interpolations and additions related specifically to Novalesa in the section containing Paul the Deacon’s Historia Longobardorum.38 This finding, which connected to the legendary history of the monastery as promoted in the Chronicle, greatly overshadowed the various texts contained in the first section of the miscellany.

While Cipolla was able to identify many of the texts contained in the first section (some of which had been described by earlier commentators), what was left unstudied proves to be a unique informant on Novalesa’s history in the eleventh century and the types of texts deemed useful to the reestablished house in order to restore, or at the very least begin to rebuild, its once expansive library. In so doing, it connects to manuscripts and monasteries within some of the same transalpine networks to which it belonged during both its Carolingian apex and its later eleventh-century Cluniac restoration.

Its direct connection to Cluny is related to perhaps the least important aspect of the manuscript, what had been described as a “Greek–Latin glossary” but is, in reality, a set of glosses taken from the Vita sancti Gregorii Magni, the four-part life of Gregory the Great by John the Deacon of Rome (also known as John Hymmonides), a cleric who worked in the papal administration of John VIII in the late ninth century.39 Although it was divorced from its original context, modern commentators had assumed that this glossae collectae in the Novalesa Miscellany was related to Isidore’s De natura rerum because the first term defined is in-deed the description and etymology of Olympias from that text. However, the rest of the glossary offers a very different set of definitions, whose only parallel comes from a now-lost manuscript viewed by Jean Mabillon and published in a short note after his death in Itineratium Burgundicum, the “Journey into Burgundy,” a record of his visit to the monastic houses and other sites in 1682.40 Mabillon’s list is substantially shorter than the glossae collectae in the Novalesa Miscellany. Both contain terms not found in the other, indicating a shared ancestor, that is, part of a manuscript in Cluny’s possession containing John the Deacon’s vita of Gregory. Due to its form, the glossary in the Miscellany served little purpose unless one was reading the vita, a text not included in the collection. Yet despite these limitations, it was deemed valuable enough to include, perhaps because of its provenance.

Provenance may have also dictated the inclusion of a number of rarely circulated short treatises, such as Heiricus of Auxerre’s Quid sit ceroma or Remigius of Auxerre’s Letter on the Hungarians, neither of which are common, but both share Carolingian pedigrees.41 On the other hand, in this eleventh-century context, a letter concerning the Hungarians could have seemed relevant. Although the Chronicle was clear on the identity of the raiders who forced the abandonment of the monastery, described uniformly as saraceni, Hungarian raids began in Italy in the first years of the tenth century, and remained a threat until their con-version.42

A further connection is made through an identification of the contents of the first twelve folios of the Miscellany, which begins imperfectly roughly sixteen folios into the Expositio missae of Amalarius of Metz and ends with Heiric of Auxerre, as a close parallel is known from Santa Maria in Ripoll (MS 206). Although dating from the twelfth century, the Ripoll manuscript includes the same rubrics and even the forms of initials, but in other ways is different. Ripoll 206 contains almost the entire eclogae of Amalarius of Metz, and after an abbreviated conclusion continues with the Exposito missae, when the Novalesa manuscript begins. Yet, the Ripoll manuscript ends in the middle of a sentence after ten lines of Heiric of Auxerre’s Quid sit ceroma, suggesting that the original manuscript may have lost its final page. In this case, like the Greek–Latin glossary, both Ripoll 206 and the Novalesa Miscellany are derived from the same family of sources.

Although their direct connection was only speculative, both Ripoll and Novalesa were connected to Cluny. Under the leadership of its abbot, Count Oliba, in the first half of the eleventh century, Santa Maria in Ripoll became a node in a network of monasteries spanning both sides of the Pyrenees, building on a tradition of interconnection, especially in the transmission of texts, between the Carolingian Empire and the region of Catalonia.43 While Cluny never made direct inroads in Catalonia to establish daughter houses, Cluny’s influence was imparted first through the Moissac Abbey in southwestern France (which was a Cluniac foundation), and later through ancillary branches connected to that monastery.44

While the first fourteen folios reflect connections to Cluny directly and perhaps through Ripoll, the largest section of the miscellany of Novalesa, ninety-three folios, is devoted to eighteen texts about saints and saintly figures that would have held relevance for the reestablished monastic community. On its surface, the organization may seem haphazard, with shorter epigrams, letters, and sermons mixed together with longer vitae. The works were not organized by literary genre, but rather generally by the position and gender of the saint and present internal coherency, according to which the subjects of the hagiographic texts can be divided into three categories: bishops and clerics, female saints, and materials related to the Virgin. The outlier from these may be the ninth-century miracles of Saint Benedict by Adrevald of Fleury, representing both the importance of monastic institutions and of pilgrimage, in this case to the shrine of Benedict in Fleury, reiterating a draw toward Gaul.

Together, these tracts represent a varied assortment of hagiographic writings of the ninth century and tenth century, as well as those of early medieval authors; crucial here is that it is not just a local collection, but one with texts commemorating both long-standing cults and those of more recent vintage, with a chronological range from those written by and celebrating figures with connections to ancient Christianity and the early Christian East up to the short poem offered in 970 by Ruotger as a eulogy for Bruno of Cologne, the brother of the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, a figure whose dynasty was celebrated in the Chronicle of Novalesa.45 The compilation of hagiographic texts in the Novalesa Miscellany suggests the placement of the monastery within the context of a wider Christian world, expansive both geographically and chronologically, one that complements its growing proximity to Cluny.

Conclusions

Even in the twilight of the early Middle Ages, the connections between Novalesa and the other monasteries of the Carolingian world remained strong. The well-known Necrology from Reichenau, published in the MGH in the supplement to the Necrologia Germaniae including the confraternities of St. Gall, Reichenau, and Farfa, includes simply the name of the mon-astery of Novalesa as an effort to include that community and what has been judged to be a list of its abbots and other leaders from before the exile in 906.46 This includes a number of prominent abbots, including:

- Godo abba [Novalesa’s first abbot] (726)

- Asinarius abba (ca. 760–770)–[F]rodoinus abba (ca. 773–814)

- Amblulfus [one of two possible abbots, a successor of Fro-doin or one known from the late ninth century] (post 814 or ca. 880)

- Hildradus [likely Eldradus, although not noted as abbot] (ca. 825–27)

- Ioseph episcopus et abba [Joseph, Bishop of Ivrea] (ca. 845)

This list was compiled by various hands, and likely served to signify a continuing relationship through the ninth century between Reichenau and Novalesa.

It is this kind of relationship that is reiterated in the Miscellany through the choices of texts it includes, but with those from Cluny rather than Reichenau. In the same ways, the careers of the abbots in the Chronicle of Novalesa first emphasize the connection to the Carolingians, often personally, and with the first push toward restoration, a shift to the Ottonians (likely to balance the relationship with the counts and later margraves of Turin). Counter to this, the development of Novalesa’s hagiographic corpus is through the addition of primarily local and regional saints.

The texts used to rebuild Novalesa did not recreate the institution, its library, or the political and intellectual networks to which it belonged. But rather, they projected something about its uncertain status at the end of the tenth century, and its new position by the mid-eleventh.

Appendix

Endnotes

- On Abbo, see Patrick J. Geary, Aristocracy in Provence: The Rhône Basin at the Dawn of the Carolingian Age, Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985).

- See Chap. 5, “Education Exchange: The Monastic Network,” in Madge M. Hildebrandt, The External School in Carolingian Society (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 1992), 108–29.

- Nicolangelo D’Acunto, “Forms of Transmission of Knowledge at Saint Gall (Ninth to Eleventh Century),” in Horizontal Learning in the High Middle Ages: Peer-to-Peer Knowledge Transfer in Religious Communities, ed. Micol Long, Tjamke Snijders, and Steven Vanderputten, Knowledge Communities (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 207–15.

- Marios Costambeys, Power and Patronage in Early Medieval Italy: Local Society, Italian Politics and the Abbey of Farfa, c.700–900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- Although “spiritual families” as such are largely a product of the later Middle Ages, notably those connected to Catherine of Siena, the connection between spiritual parents and their children, and more notably between brothers, reaches back to the origins of Christian monasticism in Late Antiquity. See Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- On the Cluniac reforms, see Giles Constable, “Cluniac Reform in the Eleventh Century,” in Vom Umbruch zur Erneuerung? Das 11. und beginnende 12. Jahrhundert, ed. Nicola Karthaus, Jörg Jarnut, and Mattias Wemhoff (Munich: Fink Wilhelm GmbH, 2006), 231–46, repr. The Abbey of Cluny: A Collection of Essays to Mark the Eleven-Hundredth Anniversary of Its Foundation, ed. Giles Constable (Münster: LIT, 2010), 81–112. See also Steven Vanderputten, Monastic Reform as Process: Realities and Representations in Medieval Flanders, 900–1100 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

- These include Carlo Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia vetustiora: Raccolta degli atti e delle chronache riguaardanti l’abbazia della Novalesa, 2 vols., FSI 32 (Rome: Isituto Storico Italiano, 1898–1901); Carlo Cipolla, Ricerche sull’antica biblioteca del monastero della Novalesa (Turin: Carlo Clausen, 1894); and Carlo Cipolla, “Notizia di alcuni codini dell’antica biblioteca novalicense,” Memorie della reale accademia della scienze di Torino 2, no. 44 (1894): 193–213.

- Chronicon Novaliciense, in mgh, Scriptores Rerum Langobardorum, ed. Ludwig Bethmann (Hanover: Hahn, 1846), 73–133, and Chronicon Novaliciense, ed. Celestino Combetti (Turin: ex Regio Typographeo, 1843). Hereafter CN.

- Cronaca di Novalesa, ed. Gian Carlo Alessio (Turin: G. Einuadi, 1982), and Elizabeth Artemis Clark, “The Chronicle of Novalese: Translation, Text, and Literary Analysis” (PhD diss., UNC–Chapel Hill, 2017). I have chosen here to follow the conventional book and chapter divisions used by Cipolla and Bethmann.

- Chapter 4, “Unrolling Institutional Memories,” in Patrick J. Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 115–33, and Uwe Ludwig, “Die Gedenklisten des Klosters Novalese — Möglichkeiten einer Kritik des Chronicon Novaliciense,” in Memoria in der Gesellschaft des Mittelalters, ed. Dieter Geuenich and Otto Gerhard Oexle (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1994), 32–55.

- On the history of this manuscript, see Edward M. Schoolman, “Of Lost Libraries and Monastic Memories: Creating the Eleventh-Century Novalesa Miscellany,” Haskins Society Journal 28 (2017): 39–61. A short study of the contents also appears in Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, vol. 1, 428–29.

- Cipolla, “Notizia di alcuni,” 211.

- mgh, Diplomatica Karolinorum 1, ed. Michael Tangl (Hanover: Hahn, 1906), no. 74, 106–8 and no. 125, 174–75.

- mgh, Diplomatica Karolinorum 1, ed. Tangl, no. 225, 301–4, and Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, vol. 1, 57.

- CN, 3.2: “fuerat siquidem et ipse Francicus genere, hac nominatissimus inter proceribus Francorum. Dedit ergo pater multa terrarum predia eidem filio suo, quem tradidit monastico ordini erudiendum.”

- CN, 3.8, trans. Clark.

- CN, 3.14, trans. Clark.

- The Vita Walarici can be found in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 4, ed. Bruno Krusch (Hanover: Hahn, 1902), 157–75. On the later peregrinations of Walaric’s relics, see Kate M. Craig, “Bringing Out the Saints: Journeys of Relics in Tenth to Twelfth Century Northern France and Flanders” (PhD diss., University of California–Los Angeles, 2015).

- Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina, 2443–46. The chapel dedicated to Eldrad, with thirteenth-century frescos and twelfth-century inscriptions, remains the center of his cult.

- The vita rythmica was partially reconstructed by Bethmann in his edition; see also Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, vol. 1, 372–73.

- Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, vol. 1, 375: “Novalici, [in]monasterio. depositio beati Helderadi abbatis. Hic vir egregius ex Gallicana provintia fuit indigena […]. Ad ultimum vero venit Novalicium, quo vitam ducens celibem, et huius rei gratia factus est monachorum ferme quingentorum optimus pater.”

- CN, 2.30–31.

- On the production of Florus, see S. Tafel, “The Lyons Scriptorium (continued),” in Palaeographia Latina, part IV, ed. Wallace M. Lindsay (London: Humphrey Milford, 1925), 40–49. The now-lost letters were included as “4. Epistola sancti Elderadi ad Florum directa; 5. Rescriptum Flori ad beatum Elderadum; 6. Item Florus ad eundem abbatem.” CN, 4.

- The letter appears in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 5, ed. Ernst Dümmler (Berlin: Weidmann, 1899), 340–43. On the letter, see Pierre-Maurice Bogaert, “Florus et le Psautier: La lettre à Eldrade de Novalèse,” Revue bénédictine 119, no. 2 (2009): 403–19. A partial translation of the letter and a discussion of Florus’s position with the Carolingian tradition of textual tradition can be found in Evina Steinová, “Psalmos, notas, cantus: On the Meanings of nota in the Carolingian Period,” Speculum 90, no. 2 (2015): 439–41. The MGH edition of this letter comes from the “Bible of Ripoll” MS Vat. Lat. 5729, one of a series of illuminated bibles produced in Saint Maria in Ripoll in the 10th and early 11th centuries. Florus also wrote a poem for Eldrad on the occasion of his editing the psalter: Carmen ad Hylradem, published in mgh, Poetae Latinae aevi Carolini 2, ed. Ernst Dümmler (Berlin: Weidmann, 1884), 549–50.

- CN, 3.21: “Fuit enim hisdem Attepertus monachus et sacerdos in iam sepe dicto monasterio, scilicet in temporibus almi Frodoini. Hic famulus fuit predictae aecclesiae, tam in scientia litterarum valde imbutus, quamque in recta conscriptione scriptor velocissimus. Siquidem ipse multos et varios ac permaximos libros in eadem aecclesiam suis conscripsit temporibus. Ergo ubicumque sua manu antiquaria libros a se conscriptos inter alios invenimus, extimplo recognoscimus.” Trans. Clark.

- Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, 71–80.

- Ibid., 77: “commanentes in villa Auciatis, et dicebant quod pars aecclesie sancti Petri, monasterio Novalicio, ubi Elderado abba esse videtur, qui contra legi pigneratos abebat, vel iniuste eos in servitio replegare volebant.”

- CN, 5.21-22. The Chronicle does not describe the event, only that Arduin used a privata lex in his unsuccessful attempt; Otto restores order by publicly burning the offending document.

- CN, 5.22.

- CN, 5.31.

- CN, 5.25. A charter that specifically mentions the support of Gezo, in this case a confirmation for the community of Breme, was granted by Otto III in 998 (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomatica, Könige und Kaiser 2, Otto II & Otto III, ed. Theodor Sickel [Hanover: Hahn, 1893], 707–8), and Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, 123–27.

- CN, App. 44, trans. Clark.

- CN, 5.34, 40, 43, and 45, respectively.

- The biography presented here is abbreviated from Giuliana Giai, “Tra Novalesae Chartres: Adraldo e la Renovatio novalicense nell’XI secolo,” Benedictina 59, no. 2 (2012): 271–96.

- The prose vita mentions an oratory dedicated to Eldrad at Novalesa, which is most likely the frescoed chapel. The text of the prose vita was edited by Cipolla and appears in Monumenta novaliciensia vetustiora I, 375–98. There is an earlier vita written in meter known as the Vita Eldradi Abbatis Novaliciensis Rhythmica and published as Fragmenta vitae b. Eldradi in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Sciptores 7, ed. Georg Heinric Pertz (Hanover: Hahn, 1846), 128–30. Cipolla suggested that it dated to the tenth century (Monumenta novaliciensia vetustiora 1, 372–73).

- This shifting between monastic and ecclesiastic positions had not been unknown for the abbots of Novelesa-Breme; in 845, Joseph, bishop of Ivrea, simultaneously served as abbot.

- Schoolman, “Of Lost Libraries and Monastic Memories,” 42–43.

- For an overview of the manuscript tradition of the Historia, see Rosamond McKitterick, “Paul the Deacon and the Franks,” Early Medieval Europe 8, no. 3 (1999): 319–39, 334–37, repr. Rosamond McKitterick, History and Memory in the Carolingian World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 77–80. For a full discussion, see Waitz’s introduction in Historia Langobardorum, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Langobardorum, ed. Ludwig Bathmann and Georg Waitz (Hanover: Hahn, 1878), 28–45. A brief description of the Novalesa Miscellany appears on 42, n. 3.

- Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina, 3641 and 3642.

- Ouvrages posthumes de Jean Mabillion et de Thierri Ruinart, vol. 2. (Paris, 1724), 1–33.

- Originally attributed to Lupus of Ferrières; published as one of his letters by Ernst Dümmler in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 6 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1899), 114–17. On the new attribution of Quid sit ceroma, see Veronika von Büren, “Heiricus [Autissiodorensis] mon.,” in Clavis des auteurs latins du Moyen Âge: Territoire français 735–987, ed. Marie-Hélène Jullien and Françoise Perelman (Turnhout: Brepols, 2010), vol. 3, 375–98. Charles Beeson originally argued for the authorship of Lupus: Charles H. Beeson, “The Authorship of ‘Quid sit ceroma’,” in Classical and Mediaeval Studies in Honor of Edward Kennard Rand, ed. Leslie Webber Jones (New York: Leslie Webber Jones, 1938), 1–7.

- On both issues, see Aldo A. Settia, “Monasteri subalpini e presenza saracena: una storia da riscivere,” in Dal Piemonte all’Europa: Esperienze monastiche nella società medievale (Turin: Deputazione Subalpina di Storia Patria, 1988), 79–95, and Aldo A. Settia, “I monasteri italiani e le incursioni Saraceni e Ungare,” in Il monachesimo italiano dall’età longobardia all’età ottoniana (secc. VIII–X), ed. Giovanni Spinelli (Cesena: Badia di Santa Maria del Monte, 2006), 292–310.

- Matthias M. Tischler, “How Carolingian Was Early Medieval Catalonia?,” in Using and Not Using the Past after the Carolingian Empire: c.900–c.1050, ed. Sarah Greer, Alice Hicklin, and Stefan Esders (London: Routledge, 2019), 111–33.

- Anscari M. Mundó, “Monastic Movements in the East Pyrenees,” in Cluniac Monasticism in the Central Middle Ages, ed. Noreen Hunt (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1971), 98–122.

- On Ruotger’s Vita Brunonis, see Henry Mayr-Harting, Church and Cosmos in Early Ottonian Germany: The View from Cologne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 10–21.

- MGH Necr. Suppl., 166. The relevant section on Novalesa was also included in Cipolla, Monumenta novaliciensia, vol. 1, 279–82.

Bibliography – Primary and Reference

- Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina. Brussels, 1898–1901.

- Chronicon Novaliciense. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Langobardorum, edited by Ludwig Bethmann, 73–133. Hanover: Hahn, 1846.

- Chronicon Novaliciense. Edited by Celestino Combetti. Turin: ex Regio Typographeo, 1843.

- Cronaca di Novalesa. Edited by Gian Carlo Alessio. Turin: G. Einuadi, 1982.

- Florus of Lyon. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Poetae Latinae 2, edited by Ernst Dümmler. Berlin: Weidmann, 1884.

- Historia Langobardorum. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Langobardorum, edited by Ludwig Bethmann and Georg Waitz, 12–187. Hanover: Hahn, 1878.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomatica Karolinorum 1. Edited by Michael Tangl. Hanover: Hahn, 1906.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Diplomatica, Könige und Kaiser 2, Otto II & Otto III. Edited by Theodor Sickel. Hanover: Hahn, 1893.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 5. Edited by Ernst Dümmler. Berlin: Weidmann, 1899.

- Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 6. Edited by Ernst Dümmler. Berlin: Weidmann, 1899.

- Ouvrages posthumes de Jean Mabillion et de Thierri Ruinart. 2 volumes. Paris, 1724.

- Vatican City. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 5729. https://opac.vatlib.it/mss/detail/Vat.lat.5729.

- Vita Eldradi Abbatis Novaliciensis Rhythmica (Fragmenta vitae b. Eldradi). Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores 7, edited by Georg Heinric Pertz, 128–30. Hanover: Hahn, 1846.

- Vita Walarici. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 4, edited by Bruno Krusch, 157–75. Hanover: Hahn, 1902.

Bibliography – Secondary

- Beeson, Charles H. “The Authorship of ‘Quid sit ceroma’.” In Classical and Mediaeval Studies in Honor of Edward Kennard Rand, edited by Leslie Webber Jones, 1–7. New York: Leslie Webber Jones, 1938.

- Bogaert, Pierre-Maurice. “Florus et le Psautier: La lettre à Eldrade de Novalèse.” Revue bénédictine 109, no. 2 (2009): 403–19. DOI:10.1484/J.RB.5.100498.

- Cipolla, Carlo. Monumenta novaliciensia vetustiora: Raccolta degli atti e delle chronache riguaardanti l’abbazia della Novalesa. FSI 32. 2 volumes. Rome: Isituto Storico Italiano, 1898-1901.

- ———. “Notizia di alcuni codini dell’antica biblioteca novalicense.” Memorie della reale accademia della scienze di Torino 2, no.44 (1894): 193–213.

- ———. Ricerche sull’antica biblioteca del monastero della Novalesa. Turin: Carlo Clausen, 1894.

- Clark, Elizabeth Artemis. “The Chronicle of Novalese: Translation, Text, and Literary Analysis.” PhD diss., UNC–Chapel Hill, 2017.

- Constable, Giles. “Cluniac Reform in the Eleventh Century.” In The Abbey of Cluny: A Collection of Essays to Mark the Eleven-Hundredth Anniversary of Its Foundation, edited by Giles Constable, 81–112. Münster: LIT, 2010.

- ———. “Cluniac Reform in the Eleventh Century.” In Vom Umbruch zur Erneuerung? Das 11. und beginnende 12. Jahrhundert, edited by Nicola Karthaus, Jörg Jarnut, and Mattias Wemhoff, 231–46. Munich: Fink Wilhelm GmbH, 2006.

- Costambeys, Marios. Power and Patronage in Early Medieval Italy: Local Society, Italian Politics and the Abbey of Farfa, c.700–900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511496271.

- Craig, Kate M. “Bringing Out the Saints: Journeys of Relics in Tenth to Twelfth Century Northern France and Flanders.” PhD diss., University of California–Los Angeles, 2015.

- D’Acunto, Nicolangelo. “Forms of Transmission of Knowledge at Saint Gall (Ninth to Eleventh Century).” In Horizontal Learning in the High Middle Ages: Peer-to-Peer Knowledge Transfer in Religious Communities, edited by Micol Long, Tjamke Snijders, and Steven Vanderputten, 207–15. Knowledge Communities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019. DOI: 10.2307/j.ctvnb7nbt.13.

- Dell’Oro, Ferdinandom, and Gionata Brusa. Un compendio del “Martyrologium Adonis” proveniente dall’Abbazia di Novalesa. Rome: Centro Liturgico Vicenziano, 2012.

- Dubois, Jacques, and Geneviève Renaud. Le Martyrologe d’Adon, ses deux familles, ses trois recensions. Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1984.

- Geary, Patrick J. Aristocracy in Provence: The Rhône Basin at the Dawn of the Carolingian Age. Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

- ———. Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Giai, Giuliana. “Tra Novalesa e Chartres: Adraldo e la Renovatio novalicense nell’XI secolo.” Benedictina 59, no. 2 (2012): 271–96.

- Hildebrandt, Madge M. The External School in Carolingian Society. Boston and Leiden: Brill, 1992.

- Iogna-Prat, Dominique. Agni immaculati: Recherches sur les sources hagiographiques relatives à Saint Maieul de Cluny (954–994). Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1988.

- Ludwig, Uwe. “Die Gedenklisten des Klosters Nova-lese — Möglichkeiten einer Kritik des Chronicon Novaliciense.” In Memoria in der Gesellschaft des Mittelalters, edited by Dieter Geuenich and Otto Gerhard Oexle, 32–55. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1994.

- Mayr-Harting Henry. Church and Cosmos in Early Ottonian Germany: The View from Cologne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199210718.001.0001.

- McKitterick, Rosamond. History and Memory in the Carolingian World . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511617003.

- ———. “Paul the Deacon and the Franks.” Early Medieval Europe 8, no. 3 (1999): 319–39. DOI: 10.1111/1468-0254.00051.

- Mundó, Anscari M. “Monastic Movements in the East Pyrenees.” In Cluniac Monasticism in the Central Middle Ages, edited by Noreen Hunt, 98–122. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1971. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-00705-9_7.

- Rapp, Claudia. Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016. DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195389333.001.0001.

- Schoolman, Edward M. “Of Lost Libraries and Monastic Memories: Creating the Eleventh-Century Novalesa Miscellany.” Haskins Society Journal 28 (2017): 39–61. DOI: 10.1017/9781787441446.004.

- Settia, Aldo A. “I monasteri italiani e le incursioni Saraceni e Ungare.” In Il monachesimo italiano dell’età longobardia all’età ottoniana (secc. VIII–X), edited by Giovanni Spinelli, 79–95. Cesena: Badia di Santa Maria del Monte, 2006.

- ———. “Monasteri subalpini e presenza saracena: una storia da riscivere.” In Dal Piemonte all’Europa: Esperienze monastiche nella società medievale, 292–310. Turin: Deputazione subalpina di storia patria, 1988.

- Steinová, Evina. “Psalmos, notas, cantus: On the Meanings of nota in the Carolingian Period.” Speculum 90, no. 2 (2015): 424–57. DOI: 10.1017/S0038713415000275.

- Tafel, S. “The Lyons Scriptorium (continued).” In Palaeographia Latina, part IV, edited by Wallace M. Lindsay, 40–70. London: Humphrey Milford, 1925.

- Tischler, Matthias M. “How Carolingian Was Early Medieval Catalonia?” In Using and Not Using the Past after the Carolingian Empire: c.900–c.1050, edited by Sarah Greer, Alice Hicklin, and Stefan Esders, 111–33. London: Routledge, 2019. DOI: 10.4324/9780429400551-7.

- Vanderputten, Steven. Monastic Reform as Process: Realities and Representations in Medieval Flanders, 900–1100. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013. DOI: 10.7591/cornell/9780801451713.001.0001.

- Von Büren, Veronika. “Heiricus [Autissiodorensis] mon.” In Clavis des auteurs latins du Moyen Âge: Territoire français 735–987, Vol. 3, edited by Marie-Hélène Jullien and Françoise Perelman, 375–98. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Chapter 5 (161-190) from Social and Intellectual Networking in the Early Middle Ages, edited by Michael J. Kelly and K. Patrick Fazioli (Punctum Books, 05.02.2023), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.