A recurring moment in political life when legitimacy is no longer measured by ideals, participation, or moral alignment, but by relief.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: From Revolutionary Virtue to Political Fatigue

The French Directory emerged from a revolution that had consumed its own moral vocabulary. By 1795, the language of virtue, sacrifice, and popular sovereignty remained omnipresent, yet its persuasive force had weakened. Years of upheaval, violence, and economic instability had reshaped political expectations. The question facing France was no longer how to complete the Revolution, but how to survive it. The Directory was born into this environment of exhaustion, tasked not with inspiring belief but with restoring tolerable normalcy.

This shift did not signal a rejection of revolutionary ideals. Liberty, equality, and citizenship retained symbolic importance, and few openly advocated a return to the ancien régime. What collapsed was confidence in revolutionary governance as a lived experience. The Terror had discredited moral absolutism, while Thermidor failed to produce durable stability. Revolutionary legitimacy eroded not because ideals were abandoned, but because their political expression no longer delivered safety, predictability, or economic relief.

The Directory’s unpopularity must therefore be understood as symptomatic rather than accidental. It governed a society fatigued by mobilization and suspicious of extremes. Voters and elites alike had grown wary of politics that demanded constant vigilance and sacrifice. Participation declined, enthusiasm cooled, and political allegiance became increasingly provisional. The revolutionary question shifted from who best embodied virtue to who might end the cycle of crisis.

This transformation marks a crucial moment in modern political history. Revolutionary energy did not dissipate through persuasion or repression alone. It dissipated through weariness. The Directory presided over a population that no longer sought redemption through politics, but respite from it. In this context, legitimacy was measured less by ideological alignment than by competence and calm. The conditions were set for a new kind of authority, one grounded not in revolutionary fervor, but in the promise of stability.

Thermidor and the Collapse of Moral Absolutism

The Thermidorian Reaction marked a decisive rupture in the moral economy of the French Revolution. The overthrow of Robespierre did not merely remove a faction or halt the Terror. It shattered the premise that political virtue could be enforced through uncompromising moral clarity. The language of absolute righteousness that had justified extraordinary violence now appeared dangerous rather than redemptive. Thermidor signaled the exhaustion of a politics that demanded perpetual purification.

This collapse was psychological as much as institutional. Revolutionary absolutism had depended on the belief that history itself required unyielding commitment, that hesitation was complicity, and that dissent was treason. By 1794, the costs of this worldview had become impossible to ignore. The Terror consumed allies as readily as enemies, eroding trust even among those who had once embraced its logic. Moral certainty ceased to reassure and began to terrify.

Thermidor did not restore moderation in a principled sense. It produced caution without confidence. The men who dismantled Jacobin dominance did so less out of ideological conversion than out of fear and fatigue. They sought survival, not synthesis. As a result, Thermidor cleared the stage of revolutionary absolutism without replacing it with a compelling alternative. The old moral vocabulary remained discredited, yet no new one commanded allegiance.

This vacuum reshaped political behavior. Appeals to virtue lost their mobilizing power, while accusations of extremism became potent weapons. Politics shifted from moral contestation to mutual suspicion. Revolutionary legitimacy fractured, as no faction could plausibly claim to embody the general will without provoking resistance. The Revolution entered a phase defined less by belief than by avoidance, as actors sought to distance themselves from the very language that had once propelled them forward.

Thermidor thus represents not the end of revolutionary politics, but its moral exhaustion. The ideals of the Revolution survived in abstraction, but their absolutist expression collapsed under the weight of experience. What followed was not a return to consensus, but a prolonged search for governance without transcendence. The Directory would inherit this condition, tasked with ruling a society no longer convinced that virtue could save it.

The Directory as a Regime of Distrust

The constitutional architecture of the Directory was shaped less by democratic aspiration than by fear. Its designers sought to prevent the reemergence of tyranny, whether Jacobin or monarchical, by fragmenting authority and dispersing power across multiple institutions. Executive authority was divided among five directors, legislative power split between two councils, and electoral mechanisms engineered to slow popular momentum. The result was a regime built to obstruct domination rather than to generate confidence.

This structure reflected profound distrust, not only of the people but of politics itself. Revolutionary leaders had learned to associate concentrated authority with catastrophe. As a result, the Directory prioritized restraint over effectiveness, caution over clarity. Decisions required negotiation across bodies designed to check one another, producing delay and ambiguity. While these safeguards reduced the likelihood of rapid radicalization, they also made decisive governance difficult in a society still marked by instability.

The regime’s relationship with popular participation further illustrates this anxiety. The Directory tolerated elections but manipulated outcomes through exclusions, annulments, and administrative pressure when results appeared threatening. Such interventions were justified as defensive measures against extremism, yet they eroded the credibility of representative politics. Voters increasingly understood participation as symbolic rather than consequential. Distrust flowed in both directions, hollowing out legitimacy.

The Directory thus governed without a stable foundation of consent. Its institutions were durable enough to survive crisis but too brittle to inspire loyalty. Power persisted through procedure and force rather than belief. In seeking to neutralize revolutionary excess, the Directory institutionalized suspicion, producing a political order that neither trusted nor was trusted. This mutual distrust would define its tenure and accelerate the search for an alternative capable of restoring coherence.

Electoral Volatility and the Disappearance of the Center

Elections under the Directory, under the leadership of Paul Barras, revealed not ideological polarization but political fatigue. Voter participation declined unevenly, enthusiasm proved shallow, and results shifted erratically from cycle to cycle. Rather than signaling a resurgence of radicalism or royalism, this volatility reflected uncertainty and disengagement. Citizens no longer invested in politics as a vehicle for transformation. Voting became reactive, episodic, and increasingly detached from sustained commitment.

The political center, never fully institutionalized during the Revolution, eroded further under these conditions. Moderate positions struggled to mobilize supporters in a climate defined by distrust and exhaustion. Extremes retained visibility precisely because they offered clarity, yet they failed to command durable majorities. The center did not collapse under ideological assault. It thinned through attrition, as voters withdrew rather than realigned.

Elite manipulation compounded this instability. Electoral outcomes that threatened the Directory were routinely invalidated, reinforcing the perception that participation carried little consequence. These interventions discouraged moderate engagement more than radical agitation. Fence-sitters and pragmatists learned that neutrality was safer than investment. The electoral arena became less a forum for representation than a barometer of disaffection.

This disappearance of the center proved politically decisive. Without a reliable middle, governance oscillated between containment and coercion. The Directory survived elections but lost legitimacy through them. Volatility was not a symptom of vibrant competition, but of a system running on inertia. In this environment, stability ceased to appear as a democratic outcome and instead emerged as an external necessity, preparing the ground for authority unburdened by electoral uncertainty.

Governing without Legitimacy: Corruption, Crisis, and Force

By the late 1790s, the Directory governed a republic that no longer believed in it. Lacking broad popular enthusiasm or elite confidence, it relied increasingly on expediency to maintain control. Economic instability persisted, corruption scandals proliferated, and administrative coherence weakened. These failures were not incidental. They reflected a regime attempting to function without the reservoir of legitimacy that had once sustained revolutionary governance.

Financial crisis proved particularly corrosive. Inflation, shortages, and the legacy of assignat depreciation undermined daily life and eroded trust in state competence. Efforts to stabilize the economy were uneven and often contradictory, reinforcing perceptions of ineffectiveness. For many citizens, the Revolution’s promises now translated into uncertainty and hardship. Governance appeared reactive rather than authoritative, further diminishing confidence.

Corruption scandals deepened this disillusionment. Directors and officials were widely perceived as self-interested, enriching themselves while preaching republican virtue. Whether exaggerated or accurate, these perceptions mattered politically. They stripped the regime of moral credibility without replacing it with practical legitimacy. The Directory neither embodied virtue nor delivered prosperity, leaving it exposed to criticism from all sides.

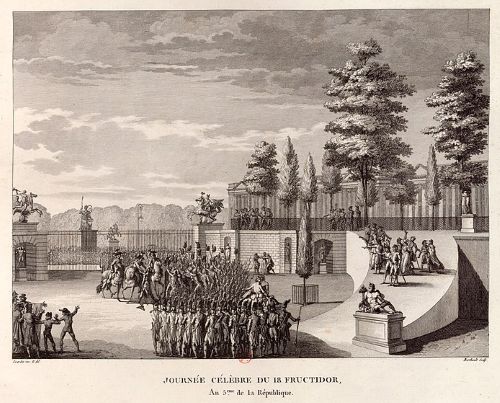

As consent evaporated, force filled the gap. The Directory increasingly relied on the army to suppress dissent, annul elections, and enforce policy. Coups such as those of Fructidor and Floréal demonstrated that constitutional norms were subordinate to regime survival. Each intervention preserved order temporarily while further undermining the idea that governance rested on law or popular will.

Governing without legitimacy proved self-defeating. Coercion stabilized the present but compromised the future. The more the Directory relied on force, the more it signaled its own inadequacy. Stability came to be associated not with republican institutions, but with military authority. In this way, crisis management became regime transformation in slow motion, preparing the ground for a leader who could claim to restore order without apology.

The Army as the Last Functional Institution

By the final years of the Directory, the French army had become the only institution capable of consistent action. Civil administration faltered, electoral legitimacy evaporated, and executive authority fragmented under mutual suspicion. The military, by contrast, retained coherence, discipline, and a clear chain of command. It delivered victories abroad when governance at home failed to deliver stability. In a republic exhausted by improvisation, functionality itself became a form of legitimacy.

This transformation was not accidental. Revolutionary warfare had fused military success with national survival, elevating the army from an instrument of policy to a guarantor of order. Soldiers were paid, supplied, and promoted more reliably than civil officials. Campaigns offered structure, purpose, and reward in a society otherwise defined by uncertainty. As civilian institutions lost credibility, the army gained it by default rather than design.

The Directory increasingly depended on military force to resolve political problems it could not manage through consent. Troops enforced decrees, suppressed unrest, and secured the regime against electoral threats. Each intervention normalized the idea that stability flowed from armed authority rather than representative governance. The army did not merely protect the state. It began to stand in for it, reshaping public expectations about where effective power resided.

This shift carried profound consequences. Once the army became the last reliable institution, political solutions gravitated toward those who commanded it successfully. Military competence came to signify administrative competence, and victory substituted for legitimacy. The Directory’s reliance on the army solved immediate crises while undermining its own claim to rule. In seeking survival through force, it elevated the very institution that would soon render it obsolete.

Napoleon Bonaparte and the Promise of Stability

Napoleon Bonaparte’s rise cannot be explained by revolutionary enthusiasm alone. By the late 1790s, ideological fervor had given way to a pervasive desire for relief from instability. Napoleon’s appeal rested less on what he promised to achieve than on what he promised to end. He did not present himself as the culmination of revolutionary virtue, but as the agent of closure. In a political culture exhausted by improvisation, competence itself became persuasive.

Napoleon’s early reputation was forged through military success, but its political significance lay in reliability rather than glory. Victories in Italy suggested decisiveness, discipline, and control, qualities increasingly absent from civilian governance. He appeared as a figure who could act without hesitation and impose coherence without endless negotiation. For a society weary of factional paralysis, this capacity to deliver outcomes mattered more than ideological purity.

Crucially, Napoleon reassured elites as much as he energized the public. He did not threaten property wholesale, nor did he revive the moral absolutism of the Terror. Instead, he signaled respect for order, hierarchy, and administrative continuity. His willingness to work with existing institutions, while quietly subordinating them, distinguished him from revolutionary radicals and Directory politicians alike. Stability, not virtue, became the new metric of legitimacy.

Napoleon’s relationship with revolutionary ideals was pragmatic rather than doctrinal. He preserved the language of the Revolution while neutralizing its volatility. Equality before the law, meritocratic advancement, and national unity were retained, but stripped of participatory unpredictability. This selective inheritance allowed Napoleon to present himself as both heir and corrective. He offered continuity without chaos, change without uncertainty.

The coup of Brumaire was thus less a dramatic rupture than an exhausted acquiescence. Resistance was limited not because Napoleon inspired universal devotion, but because alternatives had lost credibility. The Directory no longer commanded confidence, and revolutionary politics no longer promised improvement. Napoleon’s ascent was enabled by silence as much as support. Consent took the form of withdrawal rather than enthusiasm.

Napoleon’s promise of stability illustrates a recurring political dynamic. When governance fails repeatedly, legitimacy migrates toward those who can make politics feel survivable again. Napoleon did not resolve the contradictions of the Revolution. He suspended them. In doing so, he demonstrated how exhaustion reshapes political demand. The question was no longer who best embodied revolutionary ideals, but who could finally make uncertainty stop.

Exhaustion as a Political Force

Exhaustion operates in political systems as a force distinct from persuasion, repression, or ideological defeat. It emerges when repeated crises erode the emotional and cognitive resources required for sustained participation. In such conditions, citizens do not necessarily abandon beliefs. They abandon effort. Politics ceases to feel redemptive and begins to feel corrosive. The French Directory governed at precisely this point, when the population no longer sought transformation, but reprieve.

This form of exhaustion reshapes political judgment. Loyalty becomes provisional, participation minimal, and tolerance for disruption sharply reduced. Actors who promise moral renewal lose traction, not because their arguments fail, but because they demand too much. Political legitimacy migrates toward those who offer predictability, even at the cost of diminished participation. Stability becomes a value in itself, detached from ideological ambition.

Exhaustion also alters the behavior of elites. Fence-sitters, administrators, and institutional custodians prioritize continuity over conviction. They withdraw from risky alignments and gravitate toward actors who minimize uncertainty. This withdrawal is often quiet and difficult to detect, yet it is decisive. Regimes do not fall only when opposed. They fall when they are no longer defended. The Directory’s weakness lay not in rebellion, but in indifference.

The French case demonstrates that exhaustion is cumulative and self-reinforcing. Each failure accelerates disengagement, narrowing the space for democratic recovery. Once exhaustion sets in, legitimacy dissolves without spectacle. Authority reconstitutes itself elsewhere, often in forms less accountable but more functional. Exhaustion does not announce regime change. It enables it.

Conclusion: When Stability Becomes the Primary Demand

The fall of the French Directory illustrates a recurring moment in political life when legitimacy is no longer measured by ideals, participation, or moral alignment, but by relief. After years of upheaval, French citizens did not repudiate the Revolution’s principles so much as they lost faith in revolutionary governance. Politics had become exhausting rather than empowering. Stability emerged not as a conservative preference, but as a psychological necessity.

This demand for stability reshaped political judgment across social strata. Voters disengaged, elites recalibrated, and institutions drifted toward functionality over representation. The Directory failed not because it lacked revolutionary credentials, but because it could not make politics feel livable. Its collapse was quiet, procedural, and largely uncontested. When stability becomes the primary demand, legitimacy flows to those who can impose order with minimal friction.

Napoleon’s ascent thus reflects a broader structural truth. Political systems weakened by exhaustion do not resolve themselves through renewed persuasion or ideological refinement. They resolve through substitution. Authority migrates toward actors who promise closure, predictability, and control. This migration is rarely celebrated at first. It is tolerated. Acceptance takes the form of acquiescence rather than enthusiasm.

The Directory’s legacy lies in this transformation of political desire. When citizens stop asking who best represents them and begin asking who can make instability end, democratic legitimacy enters a fragile phase. Exhaustion does not destroy political systems outright. It hollows them, making space for authority that prioritizes order over participation. The lesson is not that stability is illegitimate, but that when it becomes the primary demand, the terms of politics have already shifted.

Bibliography

- Andress, David. The French Revolution and the People. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2004.

- Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. New York: Viking Press, 1963.

- Bosher, J. F. The French Revolution. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

- Broers, Michael. Napoleon: Soldier of Destiny. London: Faber & Faber, 2019.

- Caiani, Ambrogio A. “Re-inventing the Ancien Régime in Post-Napoleonic Europe.” European History Quarterly 47:3 (2017): 437-460.

- Crook, Malcolm. Elections in the French Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Dwyer, Philip. Citizen Emperor. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Forrest, Alan. Soldiers of the French Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990.

- —-. Napoleon’s Men. London: Hambledon Continuum, 2002.

- Furet, François. Interpreting the French Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Goodwin, A. “The French Executive Directory – a Reevaluation.” History 22:87 (1937): 201-218.

- Hunt, Lynn. Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Lynn, John A. Bayonets of the Republic. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1984.

- McPhee, Peter. The French Revolution, 1789–1799. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Palmer, R. R. Twelve Who Ruled. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1941.

- Runciman, David. How Democracy Ends. New York: Basic Books, 2018.

- Suthisamphat, Pumpanchat. “Napoleon Bonaparte and the Origins of Modern Europe: Napoleonic Reforms in the Grande Armée and the Rhineland.” Journal of Arts & Humanities 7:6 (2018): 30-35.

- Tackett, Timothy. The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.20.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.