An evaluation of the discursive functions of women in Flavian Rome as constructed by various media.

By Dr. Annemarie Ambüehl

Professor of History

Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz

Abstract

This article focuses on the role played by the imperial women in the definition of Flavian vs. Neronian Rome by comparing and contrasting the literary depictions of the mothers, wives, daughters, and mistresses of the three Flavian emperors with their Neronian counterparts. However, as these are mostly retrospective constructions by post-Flavian writers (Pliny the Younger, Tacitus, Suetonius), the opposition between Flavian and Neronian tends to collapse. While Vespasian and Titus are characterized as positive figures through their dealings with women, Domitian is construed as a ‘bad’ emperor like Nero. In depicting the Flavian emperors’ relations with women, the sources thus rewrite Neronian transgressions in both senses, by overwriting them with appropriate behaviour as well as by repeating and perpetuating them.

Introduction

Habet hoc primum magna fortuna, quod nihil tectum, nihil occultum esse patitur; principum uero non domus modo sed cubicula ipsa intimosque secessus recludit, omniaque arcana noscenda famae proponit atque explicat. […] Multis inlustribus dedecori fuit aut inconsultius uxor adsumpta aut retenta patientius: ita foris claros domestica destruebat infamia, et ne maximi ciues haberentur, hoc ef f iciebatur, quod mariti minores erant.

This is the main characteristic of high status, that it allows nothing to be hidden from view; and in the case of emperors it opens not only their houses but even their bedrooms and most intimate retreats, and it reveals and displays every secret for rumour to learn. […] For many famous men were put to shame because they married a wife without proper consideration or kept her too long due to indulgence. In this way their disgrace deriving from family matters destroyed their public and political reputation, and their unsuccessful role as husbands prevented them from being regarded as the best among the citizens.

(Plin. Pan. 83.1 and 4)1

With this cautionary tale Pliny the Younger addresses the emperor Trajan in his Panegyricus, delivered in the Senate in 100 CE. However, as Pliny duly adds, Trajan does not need such warnings at all, for he himself sets the example for the exceptional modesty and self-restraint exhibited by his wife Pompeia Plotina and his sister Ulpia Marciana (Pan. 83 – 84).2 In praising his addressee’s irreproachable public as well as private conduct and contrasting it (albeit only by implication) with the notorious transgressions of his predecessors, Pliny exhibits literary strategies of panegyric and elite self-fashioning, stereotypes of gender and class, and political biases that are typical of Latin imperial literature. At the same time, with his reference to rumour (fama), Pliny betrays his audience’s interest in the private lives of the emperors and their families, a preoccupation observable also in the writings of contemporary historians and biographers such as Tacitus and Suetonius. The quote from Pliny may thus serve as a good point of departure for an inquiry into the ways in which the female members of his predecessors’ dynasties were represented and how this reflects upon the overarching topics of this volume, especially the construction and almost immediate deconstruction of a dichotomy between ‘Neronian’ and ‘Flavian’ in Flavian and post-Flavian writers. While the ideological repercussions of the transition from Nero, the last Julio-Claudian emperor, to the Flavians have attracted a fair amount of scholarly debate, the role played by the imperial women (or rather their constructed images) in this process has been somewhat underrated compared to the attention paid to the emperors themselves.3 The present article therefore continues the focus on the ‘family matters’ that were introduced in Gallia’s study (in this volume) related to the Flavians’ complex negotiations with the legacy of Nero’s deified stepfather Claudius (for example, the dynastic importance of Agrippina as the widow of one emperor and the mother of another), but it turns the focus more decidedly from the male family members to the female ones and their roles in complicating any simple opposition between the Julio-Claudian and the Flavian dynasties.

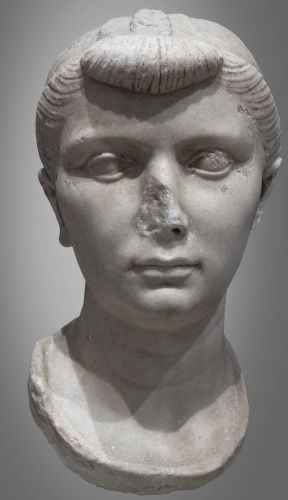

The present article does not aim at a historical reconstruction of the actual roles fulfilled by the imperial women, but rather at an evaluation of their discursive functions as constructed by various media.4 For the present purpose, iconographic testimonies such as portrait busts, statues, and coins that reflect their images in official discourse will be left aside, although in the light of the opposition construed by the (later) literary sources, it might be illuminating to ask whether the Flavians actually wanted to create a new programmatic image of their female family members in order to distance themselves from Julio-Claudian practice.5 Instead, this article will focus on the literary depictions by comparing and contrasting the mothers, wives, daughters, and mistresses of the three Flavian emperors with their Neronian (and other Julio-Claudian) counterparts.6

Yet such an investigation encounters several problems, first of all a problem connected to the nature of the sources. Due to a lack of contemporary testimonies (with the partial exception of some Greek epigrams from the Neronian period and poems by Statius and Martial),7 the texts we are dealing with are mostly retrospective constructions of both Neronian and Flavian women by later writers active under yet another generation of emperors, the so-called adoptive emperors.8 As the passage from Pliny quoted at the outset of this chapter illustrates, the strategies by which the new Flavian dynasty distanced itself from their predecessor Nero were repeated after the assassination of Domitian, when the last Flavian emperor came to figure as the bête noire from the perspective of Nerva and especially Trajan.9 When interpreting these post-Flavian texts, we therefore have to take into account a double process of construction and deconstruction, whereby Flavian responses to Nero’s Rome have been reflected, filtered, and possibly distorted to some degree through Trajano-Hadrianic responses to such Neronian and Flavian issues, an inevitable methodological problem that will also be addressed by Schulz in her contribution on the historiographical and biographical sources.

Moreover, as recent studies of gendered stereotypes in Latin historiography and biography have convincingly argued, the portraits of the imperial women in Tacitus and Suetonius mainly serve to characterize their male counterparts as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ emperors, respectively, depending on the level and success of control they exercise over the female members of their households.10 Another critical factor is the part played by the women in the transmission of imperial power from one generation to the next, as is evident in Agrippina’s crucial role as wife of Claudius and mother of Nero.11

Such biases inherent in the ancient narratives have to be taken into account in any scholarly inquiry. Still, the aim of the present study is not a rehabilitation of the allegedly ‘wicked’ imperial women (as has been attempted for the ‘bad’ emperors Nero and Domitian),12 let alone the recovery of the historical truth behind their images, but rather a discourse analysis which discusses on a meta-level the leitmotifs and stereotypes employed (sometimes in a self-conscious way) by the ancient writers and the functions they assume in defining the distinctions between the Julio-Claudian and the Flavian dynasties. In this context, ‘transgressions’ are to be understood as deviations from the discursively constructed ‘norms’ (especially related to sexual behaviour) that are stated explicitly or implicitly in the ancient texts.13 Therefore, as a first step the opposition constructed in the literary sources between the Neronian and the Flavian women will be analysed as part of the strategy of representing the Flavians as a fresh start after the reign of Nero and the year of the four emperors. But this construction is quickly deconstructed again, as the opposition between ‘Flavian’ and ‘Neronian’ collapses in hindsight.14 Soon the stereotypes associated with Nero’s and other Julio-Claudians’ transgressive relations with women return again. While Vespasian and Titus are characterized mainly as positive figures through their dealings with women, the last Flavian emperor, Domitian, is construed as a ‘bad’ emperor in analogy to the last Julio-Claudian emperor Nero, not in the least through his problematic relations with his wife and his alleged incestuous relationship with his niece.15 In depicting the Flavian emperors’ relations with women, our sources thus rewrite Neronian transgressions in both senses, by overwriting them with seemingly appropriate behaviour as well as by repeating and perpetuating their negative patterns.

Neronian Women and the Year of the Four Emperors: Transitions

Readers of Tacitus and Suetonius (along with the pseudo-Senecan Octavia and Cassius Dio, respectively his epitomator Xiphilinus) are familiar with Nero’s problematic and even transgressive relations with the women in his life, and many modern scholars and writers have constructed their own, more or less sensational narratives based on these sources.16 It is interesting to see how the same texts have been received in widely differing ways, from misogynist reproductions of the ancient male writers’ prejudices to feminist readings fascinated by the powerful imperial women of ancient Rome.17 Yet in the end it is important to realize that the power ascribed to them (especially in Tacitus’ imaginative account) ultimately derives from the male emperors, and that with a few notable exceptions these women were not empowered to take their own decisions concerning political matters or even their own private lives.18 Unfortunately, Agrippina’s memoirs, which could have painted a different picture (or perhaps not?), have not been transmitted.19

The basic outline of the Neronian story starts with Agrippina the Younger, the power-obsessed mother who after murdering her husband-uncle Claudius helps her young son Nero to the throne and does not refrain from incestuous advances in order to keep her influence on him. But to no avail, as she is finally killed by her own son. Nero’s wives and mistresses undergo similar fates. To mention only the most notorious examples: his first love, the freed-woman Claudia Acte, is drawn into the power play between Agrippina and her son but then disappears from the literary record, only to reappear as one of Nero’s last faithful followers at his burial. In contrast, the political marriage to his stepsister Octavia was doomed from the start, ending with her exile and death. His second wife, Poppaea Sabina, whom, according to one version, he had stolen from Otho, he allegedly killed by kicking her while she was pregnant. Finally Antonia, another daughter of Claudius and a sister of Octavia, who refused to marry Nero after Poppaea’s death, was executed under the pretence of a conspiracy, while Nero killed the husband of his third and last wife, Statilia Messalina, in order to marry her, not to mention his extravagant marriages to his ‘wife’ Sporus (alias Sabina) and his ‘husband’ Pythagoras (according to Tac. Ann. 15.37.4) or Doryphorus (according to Suet. Ner. 29).

In this narrative, parricide, incest, adultery, and other sexual transgressions constitute an interesting mixture, and these are exactly the ingredients that will make a reappearance (if sometimes only ex negativo) in the biographies of Nero’s successors. In the context of the transition from Nero’s reign to Vespasian during the year of the four emperors, the role of women is not very prominent, but probably not by coincidence, they mainly pop up in ominous connection to Nero.

In Tacitus’ Histories, despite the good examples set by loyal mothers and wives as announced in the prologue (Hist. 1.3.1), women play a much less conspicuous role than in the Annals, yet here, too, they function as signposts in the turbulent phase of transition from Nero to the Flavians. The affair involving Otho as Nero’s rival in love for Poppaea Sabina is evoked in order to demonstrate Otho’s ‘likeness to Nero’ (Neronis ut similem, Hist. 1.13.3 –4).20 After becoming emperor, Otho has the statues of Poppaea officially resurrected in memory of his love for her; as a (perhaps consciously intended) side effect this evokes the memory of Nero, too, whereupon he is greeted as ‘Nero Otho’ by the populace (Hist. 1.78.2). Tacitus also notes that Otho lusted for the sexual transgressions that were common under Nero’s reign and was encouraged by his freedmen and slaves to usurp power in order to indulge his desires for ‘the luxury of Nero’s court, adulteries, multiple marriages and all the other lusts f it for kings’ (aulam Neronis et luxus, adulteria matrimonia ceterasque regnorum libidines, Hist. 1.22.1). In this context it does not come as a surprise that Nero’s former ‘magistra libidinum’, Calvia Crispinilla, was protected by Otho, as well as by Galba and Vitellius (Hist. 1.73).

Vitellius himself is characterized negatively, too, through his indirect association with Nero, who had mixed private and political matters in his crimes, which were connected to his love life (Hist. 2.63–64). First, Vitellius has Dolabella murdered, the hated soon-to-follow new husband of his ex-wife, Petronia, which was received ‘with great indignation and considered a (bad) first sign of the new principate’ (magna cum inuidia noui principatus, cuius hoc primum specimen noscebatur, Hist. 2.64.1).21 This impression is confirmed by the ‘unwomanly’ cruelty of his brother’s wife, Triaria, who (from the perspective of a later reader who can compare both works) is depicted as a second ‘quasi-male’ Agrippina by subtle verbal parallels with the Annals: Triaria is ‘fierce beyond a woman’ (ultra feminam ferox, Hist. 2.63.2), just like Agrippina and her alleged ‘fierceness’ and ‘lack of restraint’ (contra ferociam Agrippinae, Ann. 13.2.2; Agrippina ferociae memor, Ann. 13.21.2; ferox atque impotens mulier, Suet. Ner. 28.2).22 The negative example of Triaria is then contrasted with Vitellius’ own wife, Galeria, and his mother, Sextilia, who are characterized as paragons of modesty and ‘old-fashioned virtue’ (antiqui moris, Hist. 2.64.2).23 The contrasting images of Vitellius’ female family members thus sketch an ambiguous picture of his principate that could develop in different directions.

It seems very likely that also in the remainder of the Histories Tacitus highlighted the role of the imperial women in order to mark the rise and fall of the Flavian dynasty, just as he does when treating the Julio-Claudian dynasty in the Annals, although this is impossible to prove due to the loss of most of the Histories’ Flavian books. From this perspective, the denigrating remark about Domitian ‘playing the emperor’s son through sexual transgressions and adulteries’ (stupris et adulteriis filium principis agebat, Hist. 4.2.1) right at his first rise to power after Vitellius’ downfall, even if his behaviour is partly excused by his young age at the time, may have functioned as a teaser to introduce a topic that was to be elaborated further in the later books.

A similar picture emerges from Suetonius. In the Life of Galba (5.1), the marriage theme is introduced first in a mainly positive sense, for Galba, after losing his wife Lepida and two sons by her, abstained from remarrying. But even while his wife was still alive, he was stalked by the freshly widowed Agrippina, who tried to seduce him so shamelessly that she was slapped by Lepida’s mother in front of the gathered matrons. Although this anecdote plays a long time before Galba was to become emperor and even before Agrippina’s marriage to Claudius, the memory of Nero’s mother is planted early in the Life as a sign that Galba was probably not to bring the change Rome was hoping for .

With Otho, the associations with Nero and his women become much more prominent, just as in Tacitus. After reporting rumours that Otho had wormed his way into Nero’s court by pretending love for an influential but old freedwoman and even may have had homosexual relations with Nero himself (Otho 2.2), Suetonius has his dubious role in Nero’s murder of Agrippina and his love affair with Nero’s mistress Poppaea Sabina (Otho 3) mark the beginning of his career, while the suicide note addressed to his fiancée, Statilia Messalina, Nero’s widow, signals its end (Otho 10.2). Otho is thus characterized as Nero’s successor not only in politics but also in love. Vitellius, on the other hand, who had had intimate relations with the emperors from Tiberius to Nero (Vit. 3–5), is associated with Neronian kin-murdering habits through the rumour that he murdered his own son, whom he had by his first wife, Petronia (Vit. 6.1); he thus even surpasses Nero, who had his young stepson, Rufrius Crispinus, Poppaea’s son, killed (Ner. 35.5).

So both in Tacitus and in Suetonius, the turbulent transitional period from Nero’s death to the rise of the Flavian dynasty is marked by uneasy reminiscences of Nero, especially of his transgressive relations with women and the concomitant crimes, ranging from adultery to murder of kin.24

Flavian Women and Neronian Transgressions under Vespasian and Titus: It’s All Different Now

It is up to the first Flavian emperor, Vespasian, to really make a new start, coming as he does from a relatively obscure family without potentially risky ties to the Julio-Claudians.25 The only time that a woman from Nero’s family, in this case Agrippina, is mentioned by Suetonius, Vespasian is immediately distanced from her, as it is stated that during the early reign of Nero he feared her, because of her influence over her son and her lasting hatred for his former friend Narcissus (Vesp. 4.2). Vespasian’s wife, Flavia Domitilla, plays the part of the good Roman matron, who bears his three children and otherwise is not subject to gossip (Vesp. 3).26 Interestingly enough, Suetonius quite neutrally glosses over the facts that she had once been the ‘mistress’ (delicatam olim) of a Roman knight some time before her marriage to Vespasian, and that Roman citizenship was only awarded to her after a lawsuit brought by her father, a clerk fulfilling a low position in the hierarchy.27 Such matters that potentially might reflect badly upon Vespasian himself would have gained much more attention in Lives of other emperors, where they could serve to confirm an overall negative image. But in this case, the distance of Vespasian’s wife from the high society associated with Nero’s court works to her and her husband’s advantage.

Likewise, Vespasian’s former mistress Caenis, a freedwoman of Antonia the Younger, stays decently in the background, and when after his wife’s death, which occurred before he became emperor, Vespasian openly resumes their relationship, she is treated as a respected member of the family, although not officially as his wife, even during his principate (Vesp. 3).28 This at least neutral, if not outright positive description (paene iustae uxoris loco: ‘having almost the rank of a lawful wife’) stands in implicit contrast to Nero’s aspirations to marry the freedwoman Claudia Acte. In that case Suetonius’ wording implies a strong negative judgement: Acten libertam paulum afuit quin iusto sibi matrimonio coniungeret, summissis consularibus uiris qui regio genere ortam peierarent (‘He almost went so far as to take the freedwoman Acte in lawful marriage, by producing as witnesses former consuls who swore falsely that she was born from a royal family’, Ner. 28.1). In face of the outrageously false claims concerning Acte’s lineage, the issue of Flavia Domitilla’s citizenship, too, appears as a minor matter.

The black sheep of the Flavian family is Domitian, who refused Caenis’ ‘usual welcoming kiss upon her return from Histria and offered her his hand instead’, which reflects badly on his ‘antisocial character, which he had exhibited from his youth’, not on her position as ‘his father’s concubine’ (ab iuuenta minime ciuilis animi […] Caenidi patris concubinae ex Histria reuersae osculumque ut assuerat offerenti manum praebuit, Suet. Dom. 12.3). Also Vespasian’s other amorous relations, which he took up after Caenis’ death, in no way threaten his reputation as an emperor but are the subject of anecdotes and jokes (Suet. Vesp. 21–22).

With Vespasian’s elder son and successor Titus, at first it seems as if it would be a different story29:

Praeter saeuitiam suspecta in eo etiam luxuria erat […], nec minus libido propter exoletorum et spadonum greges propterque insignem reginae Berenices amorem, cui etiam nuptias pollicitus ferebatur […], denique propalam alium Neronem et opinabantur et praedicabant. at illi ea fama pro bono cessit conuersaque est in maximas laudes neque uitio ullo reperto et contra uirtutibus summis.

Besides cruelty, he was also suspected of a luxurious lifestyle […], and not to a lesser extent also of lustful behaviour because of his swarms of male prostitutes and eunuchs as well as because of his well-known love for queen Berenice, to whom he was even said to have promised marriage. […] Eventually public opinion openly declared him to be a second Nero. But this reputation changed for the better and turned into the greatest praise, as no vice was found in him but, on the contrary, the highest virtues.

Suet. Tit. 7.1

Through his debauched lifestyle and especially his sexual escapades, the young Titus is linked so explicitly with Nero that it is feared that he would turn out to be ‘another Nero’ (alium Neronem).30 In the case of the eunuchs this can be read as a reference to Nero’s relations with Sporus (Suet. Ner. 28). In the case of Titus’ concubine Berenice, however, the analogy seems less straightforward, for the parallels with Nero’s futile attempts to legitimize his planned marriage to the freedwoman Claudia Acte are not very close.31 As we learn from Tacitus (who in Hist. 2.2 gives a similar sketch of Titus’ evolution from his youthful exuberance to his moderation as an emperor), Flavius Josephus, and Cassius Dio, Julia Berenice was a queen from the Hellenized Herodian dynasty, who together with her brother Herodes Agrippa ruled the client kingdom of Judaea and supported Vespasian and Titus during the Jewish revolt; she possessed Roman citizenship and had lived together with Titus after the death of his first wife, Arrecina Tertulla, and the divorce from his second wife, Marcia Furnilla (Suet. Tit. 4.2).32

But Titus’ plans to marry his oriental mistress did not find favour with the Romans (cf. Cass. Dio 66.15.4). These hostile reactions against an oriental queen recall a famous Julio-Claudian precedent: Julius Caesar’s love affair with the last Ptolemaic queen, Cleopatra, and the rumours that he planned to rule together with her as a king after transferring the capital of the Roman Empire to Alexandria (Suet. Iul. 79.3), not to mention Mark Antony’s even more ‘un-Roman’ involvement with her. Berenice’s visit(s) to Rome and her cohabitation with Titus might have resulted in the hitherto unprecedented marriage of a Roman emperor to an eastern and moreover Jewish queen, but ‘immediately he sent Berenice away against his will and against hers’ (Berenicen statim ab urbe dimisit inuitus inuitam, Suet. Tit. 7.2). The literary associations evoked by the tale of the separation of Titus from Berenice, a tragic romance that was to reach its full bloom only in the early modern age, cannot be discussed in detail here, but in any case it is remarkable that Suetonius gives an almost poetic touch to the unwilling farewell by a subtle intertextual allusion to the famous line uttered by Aeneas at his last meeting with Dido in the underworld, ‘against my will, my queen, I leave your shore’ (inuitus, regina, tuo de litore cessi, Verg. Aen. 6.460), itself a near-quotation from Catullus’ rendering of Callimachus’ Coma Berenices, where a lock of hair is separated against its will from the head of another queen Berenice (inuita, o regina, tuo de uertice cessi, / inuita, Catull. 66.39–40).33 Through such subtle literary reminiscences Berenice is associated with seductive eastern queens like Dido or Cleopatra, which casts Titus in the role of the Roman leader who has to resist the temptation for the sake of Rome. By renouncing his love for Berenice he thus refuses to become a second Nero, but rather turns out a second Julius Caesar, who likewise ‘after receiving Cleopatra in Rome sent her back’ (quam denique accitam in urbem […] remisit, Suet. Iul. 52.1) – or even a second Augustus.

While in Suetonius such an implication is conveyed only covertly by the allusion to Virgil’s Aeneas, who can in some ways be read as an alter ego of Caesar-Augustus, the comparison is made explicit in Cassius Dio. Shortly after mentioning Titus’ change of behaviour upon taking over the emperor-ship from his deceased father, which is confirmed by his final dismissal of Berenice (Cass. Dio 66.18.1), he compares Titus’ brief reign to Augustus’ long rule that ensured the popularity of both emperors, for Augustus became milder with time, whereas Titus might have lost his good reputation if he had ruled longer (66.18.4–5).34

In this way the Flavian dynasty, at least as far as the reign of Titus is concerned, is presented as a return to the ‘good old times’ under Augustus, a conceit that Suetonius stresses by means of a ring composition marking off the Lives of the Flavian emperors (Book 8).35 At the beginning of the Life of Vespasian, he states programmatically:

Rebellione trium principum et caede incertum diu et quasi uagum im-perium suscepit firmauitque tandem gens Flauia, obscura illa quidem ac sine ullis maiorum imaginibus sed tamen rei p. nequaquam paenitenda, constet licet Domitianum cupiditatis ac saeuitiae merito poenas luisse.

The empire, which for a long time had been unstable and almost wavering through the rebellion and murder of three emperors, was finally taken over and stabilized by the Flavian family, admittedly an obscure one and without any portraits of ancestors. Still, the state did not have to regret it at all, although it is not to be doubted that Domitian deserved the punishment he suffered for his lust and cruelty.

Suet. Vesp. 1 .1

Thus the generally positive picture of the Flavian house is marred only by the decline of its third and last representative. The implied move from the depraved last Julio-Claudian to a new, better generation of emperors is repeated at the end of the Life of Domitian, which is at the same time the very last sentence of the Lives of the Caesars:

ipsum etiam Domitianum ferunt somniasse gibbam sibi pone ceruicem auream enatam pro certoque habuisse beatiorem post se laetioremque portendi rei publicae statum, sicut sane breui euenit abstinentia et moderatione insequentium principum.

Domitian himself is said to have dreamed that a golden hump grew on the back of his neck, and he was sure that this portent announced a happier and more prosperous condition of the state after his death; and indeed after a short time this came true thanks to the self-control and moderation of the succeeding emperors.

Suet. Dom. 23.2

So the cycle starts all over again, at the same time laying bare the ideological mechanisms that inform the construction of Suetonius’ Lives with its two parallel cycles of dynastic rise, decline, and fall.36

Flavian Women and Neronian Transgressions under Domitian: It’s All the Same Again

With Suetonius’ portrayal of Vespasian and Titus and their sober relations with women, the ghosts of Nero’s transgressive women apparently had been banned. This is soon to change again with Domitian. A first disquieting sign comes near the end of the Life of Titus, when Suetonius reports speculations about the one thing that Titus regretted having done in his life:

quidam opinantur consuetudinem recordatum quam cum fratris uxore habuerit, sed nullam habuisse persancte Domitia iurabat, haud negatura si qua omnino fuisset, immo etiam gloriatura, quod illi promptissimum erat in omnibus probris.

Some people believe that he remembered the love affair he had had with his brother’s wife, but Domitia swore solemnly that they did not have sexual relations, and she would not have denied it, if there had been any such relation at all; yes indeed, she would have boasted of it, as she was absolutely ready to do with respect to all her sexual transgressions.

Suet. Tit. 10.2

The motifs of adultery, incest, and the rivalry between brothers that might even lead to fratricide evoke uncanny memories of Nero, in particular the murder of his stepbrother Britannicus and the allegations of incest with his own mother. In Suetonius’ Life of Domitian, these motifs reappear more overtly in connection with Domitian’s relations with his wife Domitia Longina and his niece Julia, Titus’ daughter.37 Suetonius paints a dark picture that stands in stark contrast to the positive image of the Flavian dynasty in the encomiastic poetry by Statius and Martial, where its living (including Domitian’s beloved puer delicatus and freedman Flavius Earinus) as well as its deceased and deified members all live together in harmony in the palace and the temple of the gens Flavia.38

In Suetonius, Domitian’s wife Domitia Longina, far from being a paragon of virtue supporting Domitian’s moral reforms and his revival of the Augustan marital laws (Dom. 8.3), is depicted as the bad, adulterous wife, who in the end even turns into the husband-murdering wife (Dom. 14.1), evoking again the Neronian paradigm of Agrippina. In the passage quoted above, the truthfulness of her claim that she did not have an incestuous affair with her brother-in-law is paradoxically confirmed not by her chastity, but on the contrary by her self-proclaimed reputation for sexual transgressions. According to Suetonius and Cassius Dio, his wife’s ‘passionate love affair with the actor Paris’ caused Domitian to divorce her and to murder Paris and other people associated with him (eandem [sc. uxorem Domitiam] Paridis histrionis amore deperditam repudiauit, Suet. Dom. 3.1, cf. 10.1; Cass. Dio 67.3.1). However, ‘after a short while he took her back because he could not bear to be separated from her, pretending that the people demanded it’ (intraque breue tempus inpatiens discidii quasi ef flagitante populo reduxit, Suet. Dom. 3.1).

Whatever the real (dynastic and/or political) reasons behind the divorce and the reconcilement may have been,39 the passionate affair of the emperor’s wife with an Egyptian actor of pantomimes called Paris (from the elite Roman point of view a disreputable profession often associated with Eastern ‘decadence’)40 almost sounds too good to be true, for it inevitably evokes the mythical paradigm of the Trojan prince Paris stealing Helen, the wife of king Menelaus. Interestingly, such an association seems to have been current already at the time or shortly afterwards, to judge from a passing remark in Suetonius on the prominent victims of Domitian’s cruelty: the emperor is said to have executed the son of the senator Helvidius Priscus, who had been put to death by his father, Vespasian, on the suspicion that he had criticized his divorce from Domitia in a play (perhaps a mime or an Atellana) on the myth of Paris and his f irst wife, Oenone (Suet. Dom. 10.4).41 Moreover, the fate of the actor Paris may recall that of his Neronian homonym Lucius Domitius Paris, a freedman of Neros’ paternal aunt Domitia Lepida. According to Tacitus (Ann. 13.19–22), Agrippina accused Domitia of ‘staging’ a political intrigue against her with the help of this actor in order to get rid of her as a rival in influence over Nero.42

Besides such possible indirect Neronian resonances of Domitia’s alleged affair with the actor Paris, the charges of adultery levelled against an imperial wife and resulting in a divorce – although not in the death of the woman in question (an option at least considered by Domitian according to Cass. Dio 67.3.1) – evoke Julio-Claudian paradigms in a more direct manner: Claudius’ openly adulterous wife Messalina as well Nero’s wife Octavia, who was ‘put to death on shamelessly false charges of adultery’ (occidit sub crimine adulteriorum adeo inpudenti falsoque, Suet. Ner. 35.2; cf. Tac. Ann. 14.60.2–3).43 But whereas Nero, according to Tacitus, was forced by ‘the people’s many and open protestations’ (crebri questus nec occulti per uulgum) to at least pretend that he had ‘called his wife Octavia back home, regretting the disgraceful act’ (his *** tamquam Nero paenitentia flagitii coniugem reuocarit Octauiam, Tac. Ann. 14.60.5),44 Domitian finds himself exactly in the reverse situation, taking back an openly adulterous wife by pretending to obey ‘the people’s wishes’ (quasi ef flagitante populo, Suet. Dom. 3.1).45 Thus his act of mercy (or infatuation) is tarnished by an echo of Nero’s crime.

Even more clearly, the circumstances under which Domitian had ‘taken Domitia away to marry her while she was still the wife of Aelius Lamia’ (Domitiam Longinam Aelio Lamiae nuptam etiam in matrimonium abduxit, Suet. Dom. 1.3; cf. post abductam uxorem, 10.2) recall several Julio-Claudian precedents. The most recent among them is Nero’s marriage to Poppaea, which involved stealing her not from one but from two men, her former husband Rufrius Crispinus and her lover Otho46:

item Poppaeam Sabinam tunc adhuc amicam eius, abductam marito demandatamque interim sibi, nuptiarum specie recepit nec corrupisse contentus adeo dilexit ut ne riualem quidem Neronem aequo tulerit animo.

Also Poppaea Sabina, who was at that time still Nero’s mistress after she had been taken away from her husband and entrusted in the meantime to him [sc. Otho], he accepted under the pretext of marriage, and not contenting himself with seducing her, he loved her so much that he could not even calmly put up with Nero as his rival.

Suet. Otho 3.1

Ultimately of course, this practice evokes Augustus’ own marriage to Livia, whom he ‘took away at once from her husband Tiberius Nero even while she was pregnant’ (statim Liuiam Drusillam matrimonio Tiberi Neronis et quidem praegnantem abduxit, Suet. Aug. 62.2; cf. 69.1),47 not to mention the wife-stealing habits of Caligula, who according to a tradition reported by Suetonius (Calig. 25.1) himself adduced the examples of Augustus and Romulus’ rape of the Sabine women.48 Likewise, the rumours that Domitia Longina took an active part in the conspiracy to murder her husband (Suet. Dom. 14.1) inevitably recall Agrippina’s murder of her husband Claudius, although in Domitia’s case, the motive could not have been the securing of her son’s succession, for the couple did not have any surviving children.49

Among Domitian’s evil deeds against his own family, Suetonius dwells especially on his incestuous love affair with Julia, the daughter of his brother Titus, whom he had refused to marry when she was still a virgin because he was devoted to his wife Domitia at that time:

non multo post alii conlocatam corrupit ultro et quidem uiuo etiam tum Tito. mox patre ac uiro orbatam ardentissime palamque dilexit, ut etiam causa mortis extiterit coactae conceptum a se abigere.

But shortly afterwards, when she had been married to another man, he seduced her himself, and indeed while Titus was still alive. Then, after she had lost her father and her husband, he loved her passionately and openly, so that he even caused her death by forcing her to abort a child she had conceived of him.

Suet. Dom. 22

In Suetonius, such incestuous relations within the imperial family take up a good old Julio-Claudian tradition. Caligula is said to have had sexual relations with his three sisters (Suet. Calig. 24), among them Drusilla, whom ‘soon after her marriage to the former consul Lucius Cassius Longinus he abducted and treated openly as his lawful wife’ (24.1: mox Lucio Cassio Longino consulari conlocatam abduxit et in modum iustae uxoris propalamhabuit). The same emperor spread a rumour about Augustus’ incestuous relationship with his own daughter Julia, from which his own mother Agrippina the Elder allegedly was born (Calig. 23.1). An even more notorious case in point are Agrippina the Younger’s marriage to her uncle Claudius (Suet . Claud. 26.3) and the incestuous overtones of her relationship with her son Nero (Suet. Ner. 28.2; cf. Tac. Ann. 14.2). In comparison with Ptolemaic sibling-marriage, such incestuous relations might be seen as a means to mark the imperial family off as a self-contained unit with divine associations (following the model of Jupiter and Juno), but from the Roman point of view, and especially from the perspective of senatorian writers, they serve to denigrate the ‘bad’ emperors.50 In Domitian’s case, the allegations of incest with his niece therefore are likely to be constructions by later authors in order to corroborate their negative image of the last Flavian emperor.51

Once again this strategy may be reinforced by an implicit association with Nero, who is said to have caused the death of his pregnant wife, Poppaea (Suet . Ner. 35.3), just as Domitian is blamed for Julia’s death.52 Moreover, Domitian’s improvised funeral (Suet. Dom. 17.3) shows clear verbal echoes of Nero’s funeral (Suet. Ner. 50). In both cases the emperor’s nurses play an important role, and while at Nero’s funeral his former beloved Acte is present, Domitian’s ashes are secretly mingled with those of Julia in the temple of the gens Flavia.53

So especially through the motifs of wife-stealing tyrants, adulterous and husband-murdering wives, and incestuous relationships within the imperial family, the last Flavian emperor, Domitian, is linked closely with Nero and the other ‘bad’ Julio-Claudians, coming round full circle after the more promising start with the first two Flavians. It is no surprise then that another motif associated with Nero’s reign especially in Tacitus and Suetonius also comes to full bloom again, namely ‘parricide and murder’ (parricidia et caedes, Suet. Ner. 33.1). Domitian’s political murders of his cousins Flavius Sabinus (Suet. Dom. 10.4), Julia’s husband, and Flavius Clemens (Suet. Dom. 15.1; cf. Cass. Dio 67.14.1–2), who was married to the daughter of Domitian’s sister Flavia Domitilla, fit this pattern well. So Suetonius quite literally deconstructs the gens Flavia in the course of the Life of Domitian, as its members are killed off one by one, not in the least because of their (self-)destructive relations with the women of the imperial family.

Some Conclusions and Perspectives

From the passages discussed above it should have become clear that these depictions of the Neronian and Flavian women in (mainly) post-Flavian writers are not direct reflections of historical reality, but rather discourse models that employ literary patterns, gender stereotypes, and political agendas in order to construct highly biased versions of history.54 Such typological correspondences and contrasts structure the narrative of the Julio-Claudian dynasty through internal parallels and cross-references, and the resulting matrices of good or bad behaviour by male and female characters can then also be transferred upon the subsequent dynasties.55 Prominent examples are charges of adultery brought against female members of the imperial family that result in their banishment or execution, from Augustus’ daughter and granddaughter, the elder and the younger Julia, to Messalina, Octavia, and Domitia Longina. Likewise, the alleged involvement of the emperor’s wife in complots surrounding her husband’s death and the choice of a successor starts right from the rumours that Livia herself may have had a hand in Augustus’ death and the murder of his potential heirs Lucius and Gaius Caesar and Agrippa Postumus, in order to secure the succession of her son Tiberius.56 This pattern is then applied to Agrippina the Younger and, once again, Domitia Longina. Ironically enough, Trajan’s wife Pompeia Plotina, who in Pliny’s Panegyricus is stylized as a paragon of virtue, as we have seen at the outset of this chapter, is accused in later sources, such as Cassius Dio (69.1.2–4), of having tampered with Trajan’s testament and having thus secured the succession of her favourite Hadrian, with whom she is even said to have been in love.

Such analogies also work in the reverse direction, as interpretative models applied to the Flavians may have been projected back onto the Julio-Claudians, notably in Tacitus’ Annals, which were written after his Histories.57 A comparative analysis of the representations of Flavian and Neronian imperial women is thus complicated by the fact that the picture of the Neronian (and indeed all the Julio-Claudian) women has largely been shaped by the same writers who also treated the Flavian emperors in retrospect. While the stock motifs associated with the imperial women, such as social status derived from male relatives and marriage versus adulterous sexual relationships or divorce, remain largely the same, by subtle manipulations and re-evaluations of single elements within this framework Tacitus and Suetonius manage to impress their ideologically shaped images upon the reader.58 The ‘good’ (and posthumously deif ied) emperors Vespasian and Titus are explicitly or implicitly contrasted with Nero, whereas Vespasian’s immediate predecessors and then again Domitian are linked with Nero and his women through parallel motifs and verbal echoes.

To some degree these literary constructions may actually reflect the individual Flavian emperors’ different responses to Nero’s Rome, for it is remarkable that, either by biographical coincidence or by conscious choice, the first two Flavians, Vespasian and Titus, had no wife at their side during their emperorship, and that their female companions Caenis and Berenice seem to have been pushed more or less to the background. It is under Domitian that we witness a full return to and further evolution of the Julio-Claudian programme of promoting the living or deceased and divinized female members of the imperial family.59 While Domitian himself thus seems to have reappropriated some Neronian precedents in the official representation of his female family members, post-Flavian writers such as Tacitus and Suetonius in the reverse sense reinforce their negative image of Domitian through a reappropriation of the negative patterns associated with the ‘bad’ Neronian women.

See endnotes and bibliography at source

Chapter 3 (55-86) from Flavian Responses to Nero’s Rome, edited by Mark Heerink and Esther Meijer (Amsterdam University Press, 09.29.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license.