The ability of professors to teach and write about controversial topics without fear of retribution is nothing new.

By Dr. Alessandro Meregaglia

Assistant Professor and Archivist

Boise State University

Introduction

In January 2023, Hamline University opted not to renew the contract of an art professor who showed a 14th-century depiction of the Prophet Muhammad in class. Hamline labeled the incident “Islamophobic” and released a statement, co-signed by the university’s president, saying that respect for “Muslim students … should have superseded academic freedom.”

After widespread backlash, the university walked back that statement. However, the lecturer was still not rehired.

Concerns about academic freedom are nothing new. Rather than being a product of recent “cancel culture,” tension has long existed over the ability of professors to freely teach and write about controversial topics without fear of retribution.

More than 80 years ago, an English professor named Samuel Steward was dismissed from his teaching position after publishing what his college’s president deemed a “racy” novel.

As an archivist and scholar studying publishing in the American West, I’ve located published and unpublished archival sources detailing the controversy surrounding Steward after he published his first novel, which ultimately cost him his job.

A Book Met with Backlash

A native of the Midwest, Steward earned his Ph.D. in English in 1934 from Ohio State University. The following year, Washington State College – now Washington State University – hired Steward to teach classes on a one-year contract.

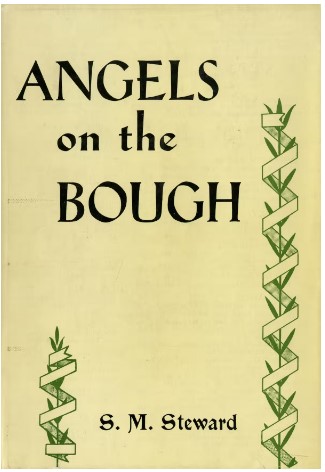

An aspiring writer, Steward drafted his first novel while still a graduate student. He worked to find a publisher and contacted a small firm in rural Idaho. After an editorial review, Caxton Printers agreed to publish Steward’s novel, “Angels on the Bough,” which told the story of a small group of characters and their intertwined lives in a college town.

Founded in 1907, Caxton Printers has earned national attention for its fierce defense of freedom of expression and unique publishing philosophy. Caxton’s founder, James H. Gipson, understood the transformative power of books and sought to give a voice to deserving writers when other firms rejected them. Profit was not a motivator. As Gipson explained to Steward, “We are interested not in making money out of any author for whom we may publish, but in helping him.”

Caxton published “Angels on the Bough” in May 1936.

The book immediately received reviews, almost entirely positive, in dozens of newspapers across the country. The New York Times wrote favorably about the novel, describing Steward as possessing “a very distinct gift above the usual.”

And Gertrude Stein, the American writer and expatriate who lived most of her life in France, lauded “Angels on the Bough” in a letter she penned to Steward.

“I like it I like it a lot, you have really created a piece of something,” Stein wrote. “It quite definitely did something to me.”

Steward Loses His Job

Despite the favorable reception, the book started causing trouble for Steward before it was even published. Review copies reached campus in early May 1936. Steward soon began hearing rumors that college administrators found his book distasteful for its sympathetic portrayal of a prostitute, one of the main characters.

Yet, as Steward noted in an interview during the 1970s, the book was “very tame – reading like ‘Little Women’ by today’s standards.”

Steward sent an urgent telegram to Gipson asking him to stop selling the book on campus: “A young poor man with only one job asks that you withdraw his novel … because his departmental head and dean hint at his discharge.”

Caxton had advertised the book as “not appeal[ing] to the less liberal mind.” This “alarmed several people,” according to Steward. The head of the English department told Steward his book contained “unsavory material” and that Steward’s position “would undoubtedly prove very embarrassing” to the college.

Despite this, Steward still planned to return to teach classes the following autumn. Earlier that spring, he had been verbally assured that he would receive another one-year contract. Three weeks later, however – and just hours before he left campus for the summer – Washington State’s president, Ernest O. Holland, summoned Steward to a meeting.

Holland informed Steward his contract would not be renewed. He accused Steward of writing a “racy” novel and of being sympathetic with a student strike a month earlier.

Angered, Steward immediately dashed off a telegram to Gipson: “Discharged by God Holland for writing a racy novel … I have no regrets whatsoever despite the fact his methods were those of Hitler but think I will take up stenography.”

Steward and Gipson both set to work to widely publicize Steward’s dismissal. Steward appealed to the Association of American University Professors for assistance. Founded in 1915, the association’s primary purpose is “to advance academic freedom.” The organization still regularly investigates violations of academic freedom, including what happened at Hamline University.

After months of investigation, the AAUP published its report. It determined that Steward had been unjustly let go and concluded that “President Holland’s handling of the Steward case has been most ill-judged, and indicates … improper restriction of literary freedom.”

From Teaching to Tattooing

After leaving Washington State, Steward promptly found a position at Loyola, a Catholic university in Chicago. Before hiring him, Loyola’s dean read Steward’s book and apparently had no objections. An AAUP member noted the irony: “Apparently our Catholic brethren are much more tolerant than a state institution in Washington.”

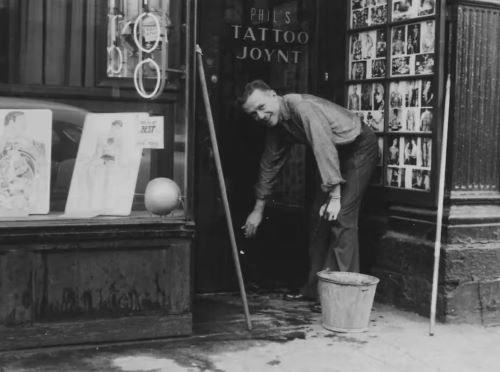

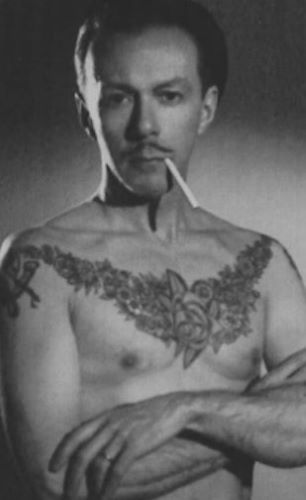

Outside of teaching, Steward, who was gay, published gay erotica under the pseudonym Phil Andros and took up tattooing. By 1956, Steward permanently left academia to ply his trade as a tattoo artist full time on Chicago’s South State Street under another alias, Philip Sparrow.

In the 1960s, he moved to California and opened up a tattoo parlor in Oakland, where he became the “official” tattoo artist for the Hells Angels motorcycle club.

After retiring from tattooing, Steward lived a quiet life in Berkeley. He still wrote frequently, producing a handful of fiction and nonfiction books. Steward died in California in 1993 at the age of 84.

Despite his prolific and varied career, Steward’s legacy as a “remarkable figure in gay literary history” was not widely known until the publication of Justin Spring’s meticulously researched 2010 book, “Secret Historian.”

Interest in Steward continues. Performance artist John Kelly recently staged a show, “Underneath the Skin,” in December 2022 that examined Steward’s life.

It is impossible, of course, to know the trajectory of Samuel Steward’s career if he had been reappointed to Washington State for another year. But a prescient comment Steward made just before his dismissal suggests that he sensed he couldn’t stay in academia forever: “I am afraid I will have to get out of the teaching profession in order to be able to write the way I want to.”

Academic freedom is related to free speech. A long-standing tradition afforded to college faculty, it shields professors from retribution – from both internal and external sources – for teaching controversial topics within their area of expertise. According to the AAUP, academic freedom is based on the premise that higher education promotes “the common good (which) depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition.”

This protection covers both classroom lectures and publications.

With debates about academic freedom lately making headlines – from outside interests influencing appointments, to administrators kowtowing to vocal students, to politicians changing oversight of public universities – Steward’s plight some 87 years ago is a reminder that this freedom requires constant defense.

Originally published by The Conversation, 02.23.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.