A class of image that traverses the poles of absorption and theatricality.

By Melina Moe and Victoria Nebolsin

This article, Scenes of Reading on the Early Portrait Postcard, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Introduction

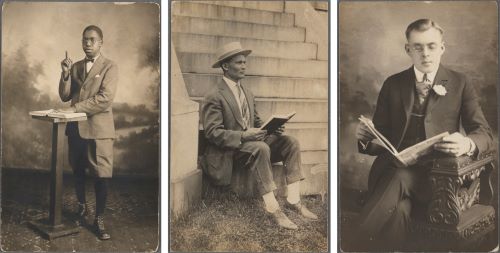

The calm scenes emerge from busy preparation. Word has spread that a traveling photographer who shoots portraits on affordable postcard-sized paper is visiting town. His patrons move through the usual rituals: carefully selecting their dress, thoughtfully studying the posted rates, a lengthy wait outside a tent at the fairground, and then a gentle arrangement of limbs, hair, attitude. The sitters and photographer discuss props. What should one hold to look serious or alluring? What object might visually meld a couple into lovers, individuals into a family? In the early twentieth century, the subjects often chose books.

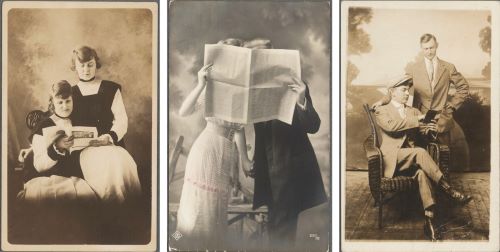

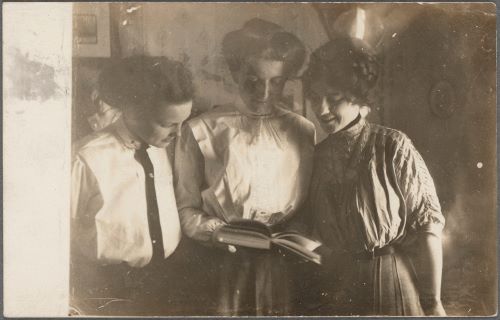

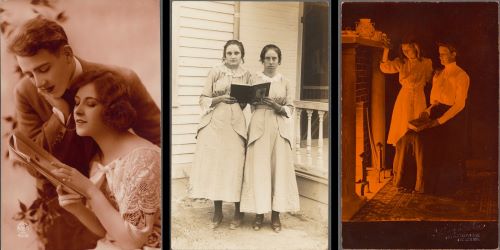

Reading takes many postures. Performances of reading, perhaps even more. These portrait postcards present readers hunched over a book in a bar, reclined in a hospital bed, and seated stiffly on a front porch. There are groups sharing a newspaper in the breakroom and young people with disregarded books on a picnic blanket. Some portraits suggest engrossed readers, while others show sitters who hold their book limply, like an unwanted package.

In the postcard above, a striking pair of young men in straw bowlers and open-necked shirts level steady gazes at the camera while holding texts; closer scrutiny reveals one to be a photography manual. Perhaps it was a prop thrust by the studio assistant into the man’s hands, then forgotten or ignored. Even so, the texts sharpen the composition, connecting elements of the scene — their heads and hands — with the imagined position of the photographer and camera. Indeed, in some photographs, books serve as additional characters, making these portraits into “double portraits” of what Karin Littau has called the active relationship between the two bodies, “one made of paper and ink, and the other flesh and blood”.1

A Wildfire of Textual Exhibitionism

Postcards were first authorized by the United States Postal Department in the 1860s. Also called “Private Mailing Cards”, the earliest postcards had no images, just a message on one side and an address on the other. In the late nineteenth century, postcards were still so new that they included instructions on how to use them. One read: “If this card, you’d send by mail. Stick 2c stamp, here, without fail.” Some early examples are printed with advertisements describing the advantages of the new medium:

This Postal Card offers great facilities for sending

Messages or for rapid correspondence.

It is only about half the price of paper and envelopes.

It is ready for instant dispatch.

It is a convenient mode for ordering goods.

It is valuable to travellers, affording ready communication.2

Other postcards were more idiosyncratic and humorous. In the UK, the oldest recorded postcard caricatures a cabal of postal workers gathered around a witchy inkpot, which the artist mailed to himself, leaving no doubt that the intended audience was not the addressee but the workers through whose hands the message would pass.3 The widespread use of postcards had a slow start, yet by the first decade of the twentieth century, the medium had taken off.

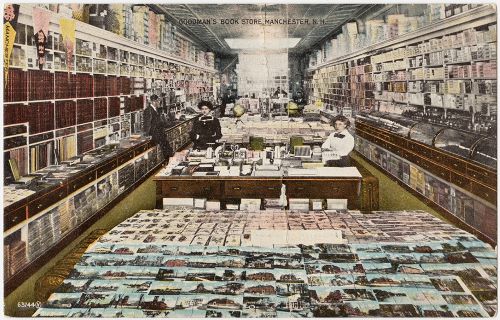

The Post Card Dealer, a short-lived magazine solely dedicated to keeping readers abreast of all things postcard, reported staggering annual numbers of specimens purchased and posted. In 1908, more than 667 million postcards were mailed in the United States; the New York postal service dealt with 200,000 postcards every week, and the New York Tribute reported a single ship that steamed into New York Harbor with 50,000 blank postcards in its cargo hold. The fad spread westward from Europe to the US, originating in the advanced printing facilities of Germany. But the largely European novelty cards were quickly imitated by US printers, eager to capitalize on the enthusiasm for mechanical postcards with intricate sliding panels and flaps that opened, postcards with transparent windows that could be held up to the light, and postcards that incorporated a baroque array of materials, from leather and silk to animal skins.4

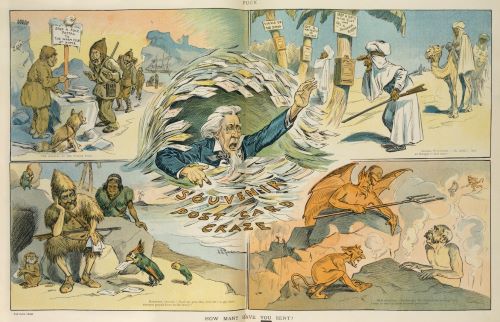

American war correspondent Julian Ralph, who made his name embedded with the Turkish army during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, took a break from his day job to report for The Cosmopolitan on “The Postal-Card Craze” sweeping Europe.5 Pro-American sentiment was expressed by collecting picture postcards of President William McKinley, whose enthusiasm for nurturing domestic industry eventually contributed to the decline of the postcard frenzy when the Dingley Act of 1897 (and later the Payne-Aldrich Act) set stiff tariffs on postcards imported from European manufacturers, whose production capacity still far outpaced the US, and the fickle taste of consumers moved on to folding illustrated cards.

The postcard became a sign of modernity even as its permeation through society allowed for a range of parodies. Woman’s Home Companion featured a cartoon in 1907 in which a woman asks, “Has this house all the modern improvements?”, with the answer: “Everything, here’s a special closet for postcards.”6 Enthusiasts were diagnosed with “postal cariditis”, The American Magazine recorded in 1906, an affliction that “affects the heart, paralyzes the reasoning faculties and abnormally increases the nerve. It had its origin in Germany, twenty years ago. . . . Sporadic cases of it were observed in the United States and the year 1900 saw the malady rapidly spread from one center of infection to another.”7 Symptoms might include mailing cards to oneself or demanding that one’s pedestrian hometown have custom postcard sets, as in “Tenafly, N. J., for instance, [where] the inmates of that New Jersey suburb awake to the fact . . . that they have no postal cards which to set forth the glories of their native place.”8

As in the case of other new media forms, the popularity of postcards of readers coincided with a burgeoning public outcry about the devastating effects of the medium on literacy itself. In 1910, The American Magazine, founded by a group of leading muckrakers which included the pioneering journalist Ida Tarbell, ran a polemic “Upon the Threatened Extinction of the Art of Letter Writing”, in which postcards were sarcastically deemed “a heaven-sent relief . . . [for] the man of few ideas and a torpid vocabulary”.9 Postcards rewarded brevity to such an extent that they threatened the prosaic art of eloquence. Tourists eager to dispatch proof of their travels were particular beneficiaries.

To the thousands of weary travelers ransacking their poorly stocked garrets for words with which to transmit the wonders they are seeing to the folks at home, the first souvenir card came like the first bit of green to the mariners in the ark. It represented one general grasp of relief—‘See for yourself; I can’t describe it.’”10

The most hardened skeptics pushed the critique into the domain of phenomenology and existentialism: postcards were being offered as a substitute for experience. What tuckered-out tourist, one satirist asked, is not glad to hear the following from their tour leader: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is the Louvre. Fifteen minutes for which to buy souvenir cards”?11

While some commentators on the postcard craze foresaw the demise of writing, others saw the new medium as fuel for a fast-spreading wildfire of textual exhibitionism. One contemporary account suggested:

When a mother decides that she will stay all night with her daughter in the next town, she sends word home to the family on a souvenir card of the Carnegie Library. When a father’s dry-goods store burns down, he photographs the catastrophe, prints a souvenir card from it and requests the insurance adjuster to drop into town immediately. . . . Baby’s arrival, his first tooth, his first trousers, his first girl, and his first baby, all go to the family circle by souvenir postal, for anyone with a camera can make his own card these days.12

The semi-public nature of postcards meant that these personal missives were shared with all who cared to turn over the card. Postcard writers, this author implied, were a convenient medium only for those who didn’t mind sharing intimate details in a public way. Though store-bought postcards display a more generic approach than personalized picture postcards, they highlight the shared urge to distribute an individual experience and correspondence under the eyes of strangers. Such a mixture of public and private messages and audiences must seem familiar not just to the “influencers” of our present age, but even to the most casual users of social media.

Absorbed Readers, Postal Performances

And yet, what was the link between postcards and readers? Why, in the heyday of postcards, did scenes of reading (or pretending to read) become a popular means of connecting people at a distance? While some early postcards included advertisements for books and publishing houses — indeed, the rise of postcards has been described by one historian as a shadow history of advertising — most of the images gathered here are “real picture postcards”: postcards printed from photographic negatives and paid for by ordinary people (not corporations) at retail photography studios.13

This subset of postcards was the realm of small-scale production and consumption. They became especially easy to make when cameras like the Kodak A3 were introduced, the large negatives of which could be developed directly onto light-sensitive, postcard-sized paper. The ease of production attracted amateurs as well as professional artists. (Photographer André Kertész made some of his most striking early experimental images on postcards.14) And the images of readers captured much that was new and playful about the medium, which in the form of real picture postcards seemed as much about self-expression as about communication.

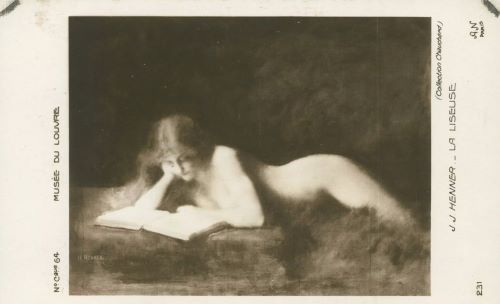

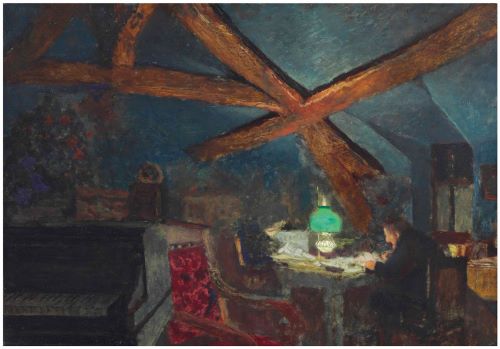

Books had long been included in visual art — and portraits in particular — as evidence of the sitter’s seriousness or accomplishments, elements of a visual grammar meant to be decoded by the viewer. Books could telegraph a sitter’s achievement in the arts of learning, just as dyed cloth, blown glass, or maps might point to the extent of a merchant’s trade network or a landowner’s net worth. But in contrast to previous centuries, art historian Michael Fried argued in his landmark Absorption and Theatricality (1976), these props took on new meanings in the eighteenth century. While once meant to directly engage or communicate a message to the viewer, books — as well as musical instruments, embroidery, or simply the facial expressions of thought — were used by painters in the eighteenth century to indicate the active internal lives of those depicted. The course of art history took a turn, Fried says, when paintings turned away from viewers.

Fried saw painters in this period, like Jean-Siméon Chardin or Jean-Baptiste Greuze, challenging a widespread and commonsense assumption about paintings: that they implied the presence of a viewer. Chardin’s Un Philosophe occupe de sa lecture (1753) or Greuze’s Un pere qui list la Bible (1755), for example, depicted figures who, instead of staring out of the picture frame, seemed consumed by their own world. The intensity of their concentration is demonstrated through moments of “self-forgetting”: a philosopher so sunk in thought as to be oblivious of the dinginess of his study, or a woman so caught up in listening to the Bible read aloud that she can ignore the chaos of children and dogs erupting around her. Absorbed in their own doings — reading, listening to music, playing an instrument — these figures are “anti-theatrical”, that is they are “being in” their world, not “acting [it] out” for viewers like us.

Fried’s explanation of how reading and similar absorbing activities in visual art became a shorthand for mental interiority falls in line with classic explanations of other media forms. In the novel, “character” was no longer a list of characteristics, as perhaps it was in chivalric literature (my love is beautiful, brave, faithful, etc.) or religious allegories (in Pilgrim’s Progress, the protagonist Christian is well, Christian). Instead, characters were individuated and, to some degree, unknowable (why did Emma Bovary throw over her bourgeois life?).15 But Fried allowed that even activities meant to indicate deep interiority, which seemingly turn away from the viewer, solicit the attention, admiration, or scrutiny of an audience. Reading fell squarely into the category of ambivalent activities; images of readers might depict them as lost in a book, coyly performing, or both.

How do portrait postcards differ from earlier paintings of people reading? While some paintings of readers would have been commissioned by their sitters, nearly every portrait postcard was an act of self-expression — and it was a form of self-expression with a uniquely outward direction, capable of spanning greater distances than canvases mounted on walls. Both propagate a vision of interiority, but portrait postcards are explicitly addressed, aimed at one set of eyes, while passing — along the postal route — beneath the gaze of all who care to look. If painting, as Fried says, turned away from viewers, postcards of reading depict subjects consumed in interiority, who, in turn, posted images of this consumption widely out across the world toward a particular destination. Like an enviable Instagram post, at least two potential relationships to the viewer are fused: one in which the beholder is ignored, and the other in which the beholder is essential. From the first perspective, the image says: “this is for me; I’m living my best life!” From the second, the image says to the viewer, “I made this picture just for you.”16

And yet, even though portrait postcards sent images of their reading subjects out into the world, they also maintained a certain secrecy. In The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond, Derrida put forward the concept of the “postal principle” to describe the distance that is both spanned and reinforced by a message flying from its sender (destinateur) to its receiver (destinataire), a principle he considered even more important than Freud’s pleasure principle for understanding Western culture. If Derrida’s idea has at its heart a form of physical distance, then postcards of readers manifest this principle on the emotional plane: the sender’s self is at once shared and held in reserve. As sociologists Gary Alan Fine and Shannon Fitzsimmons discovered in their ethnographic study of where and how people read in public, the privacy of reading is partially maintained even when performed in front of others, which holds for performances of reading placed before public eyes, too. Short of slamming a book shut in disgust, or communicating a general attitude of leisure or studiousness, the absorbed reader gives off few clues as to her feelings about a text.

Photographs of readers, as Andre Kertesez’s photography collection On Reading proves, can only unveil so much about this “secret life”. Indeed, in offering oneself up as an image, a performer surrenders to a viewer’s interpretation. As Roland Barthes wrote, images “represent the very subtle moment when [the person being photographed is] neither subject nor object, but a subject who feels he is becoming an object”.17 What the “hot dudes reading”, for example, are doing with their books on the eponymous Instagram account is up for debate. Similarly, this collection of postcards depicting readers and books is idiosyncratic and often cryptic. The most common genre of postcards was certainly, Greetings from. . . Niagara Falls, San Francisco, etc. The existence of postcards of reading shows how, at the origins of a new medium marked by its own ambivalent modernity, we returned to books to think about how we wanted to express and present ourselves.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Karin Littau, Theories of Reading: Books, Bodies, and Bibliomania (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2007), 2.

- Lipman’s Postal Card, 1861. Available here.

- BBC News, “Oldest postcard sells for £31,750”, March 8, 2002. Available here.

- George and Dorothy Miller, Picture Postcards in the United States, 1893-1918 (New York: Clarkson Potter, 1976), 22.

- Julian Ralph, “The Postal-Card Craze”, The Cosmopolitan: A Monthly Illustrated Magazine, vol. 32 (November, 1901–April, 1902): 421–26. Available here.

- The account in this paragraph of the thriving “postcard era” is derived from chapter 2 of George and Dorothy Miller’s Picture Postcards.

- John Walker Harrington, “Postal Carditis and Some Allied Manias”, American Illustrated Magazine, vol. 61 (November, 1906), 562–63. Available here.

- Ibid., 565.

- George Fitch, “Upon the Threatened Extinction of The Art of Letter Writing”, The American Magazine, vol. 70 (May–October, 1910): 172. Available here.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 173.

- Ibid.

- George and Dorothy Miller, Picture Postcards, 1.

- The High Museum recently exhibited postcards that André Kertész made during his early years in Paris, images of which are available here.

- For the most canonical take on the importance of characters for novels, see Ian Watt’s Rise of the Novel, but for other examinations of how characters are related to the elaboration of interiority, see for example Charles Taylor, Sources of the Self (1989), Deirdre Lynch, The Economy of Character (1998), and Dror Warhman, The Making of the Modern Self (2004).

- Even when these postcards show cozy scenes of communal reading — soldiers taking a break together, families poring over the same volume, patients convalescing — these groups are also engaged in the dissemination of selfhood. (Such photographs, too, are performances, not least because the practice of communal reading even at the turn of the twentieth century was increasingly rare, having steadily declined over the past two hundred years with rising literacy rates and falling book prices allowing individuals to pursue reading in solitude.)

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 14.

Public Domain Works

- “The Post-Card Craze”, Julian Ralph (1902)

- “Postal Carditis and Some Allied Manias”, John Walker Harrington (1906)

- “Upon the Threatened Extinction of The Art of Letter Writing”, George Fitch (1910)

- “People Reading in Art”

- “Portrait Photographs with Books”

Further Reading

- Picture Postcards in the United States, 1893-1918, by George and Dorothy Miller

- Open Letters: Russian Popular Culture and the Picture Postcard, 1880-1922, by Alice Rowley

- The Picture Postcard: A Window Into Edwardian Ireland, by Ann Wilson