The exact mechanism by which storms formed was once a subject of fierce debate among American scientists.

By Alyson Foster

Library Specialist

Administrative Office of the United States Courts

To fully appreciate the modern-day marvel that is the National Weather Service, it’s useful to start with numbers. There’s 6.3 billion. (The number of observations the agency collects and analyzes every day.) There’s 1.5 million. (The number of forecasts it issues each year.) There’s 184 and 100,000. (The number of weather balloons NWS releases every day, including on weekends and holidays, and the number of feet said balloons can rise into the atmosphere.) And there’s 90 percent. (The average accuracy of a five-day forecast.)

There’s also zero. That’s the approximate number of minutes a typical American like you or me spends wondering about the weather information we access every single day via print newspapers or public radio stations or the hour-by-hour forecasts delivered courtesy of the phones we carry. The ubiquitousness of those updates, the fact that we don’t consider them at all, is a testament to just how much modern meteorology has spoiled us and—probably more than anything else—a tribute to the National Weather Service’s success.

This blasé attitude would have astounded the colonists who arrived in the New World from Europe during the seventeenth century and found North American weather to be, in a word, hellish. They sent letters home describing the climate in apocalyptic terms. When it rained, wrote one colonist in New Sweden, on the Delaware River, “the whole sky seems to be on fire, and nothing can be seen but smoke and flames.” “Intemperate” was how a missionary from Rhode Island described it. “Excessive heat and cold, sudden violent changes of weather, terrible and mischievous thunder and lightning, and unwholesome air” created an environment that was “destructive to human bodies.”

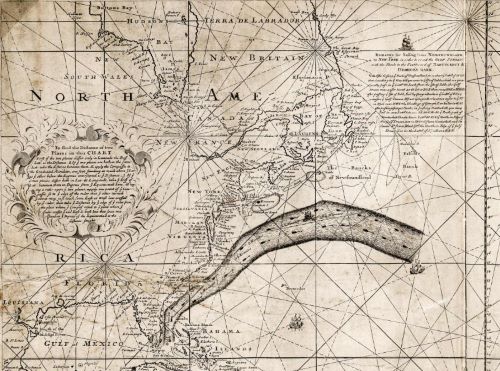

The harshness of the weather—with its extreme seasons and severe storms—wasn’t just an unpleasant surprise. It was also confusing. Among the various, sketchy assumptions that the Europeans had brought with them to their new home was the idea that a location’s climate was directly correlated to its latitude. By the colonists’ logic, the seasons in Newfoundland should resemble those in Paris, and crops grown in Spain should thrive in Virginia. Instead, the olive trees imported from the Mediterranean died in the frozen ground during the mid-Atlantic winters, and the beer went sour in the summer heat. American settlers could have consulted with the resident experts—the Native Americans who had lived in the eastern part of the continent for thousands of years and knew more about the local climate than anyone else. But they generally didn’t. (“Descriptions of local indigenous knowledge in early colonial narratives,” the historian Sam White noted in his book A Cold Welcome, “are mostly conspicuous by their absence.”)

The volatile weather in the eastern United States differs from the more moderate climates of western Europe because it is largely controlled by eastward-flowing air masses that approach over land instead of air masses that arrive from over the ocean and cause temperatures to shift more gradually. And the tail end of a regional cooling period known as the Little Ice Age was, at the time of the Europeans’ arrival, still exacerbating North American winters. But the colonists had no way of knowing either of these things. Instead, the weather remained an intriguing and stubbornly unpredictable puzzle, one that was soon taken on by the new Americans who began to collect their own data, taking measurements and comparing notes with fellow observers.

A surprising number of Founding Fathers were weather enthusiasts, among them James Madison, the avid storm-tracker Benjamin Franklin (credited, among his other more electrifying feats, with first charting the Gulf Stream), and George Washington, who kept weather diaries on and off, making his final entry on the wintry December day before he died: “Morning Snowing & abt. 3 Inches deep.”

It’s safe to say, however, that no American president was as enthusiastic about meteorology, nor as obsessive in his data collection, as Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s first existing weather journal begins on July 1, 1776, while he was in Philadelphia for the signing of the Declaration of Independence. For the next 50 years (with some occasional lapses) he meticulously logged his observations in columns that tracked barometric pressure readings, wind speeds, temperature, and other natural phenomena such as frosts and springtime bird sightings. The notes he left are so detailed and extensive that researchers are currently in the process of digitizing them so they can learn more about what those seemingly baffling weather patterns of the eighteenth and nineteenth century might tell us about our own.

Jefferson was a proselytizer for weather diaries—he was the one who sold his fellow president Madison on the idea of keeping one—and he communicated with correspondents as far north as Québec and as far south as Mississippi about their observations. Various distractions (serving as minister to France, founding the University of Virginia, a stint as the nation’s third president) prevented him from achieving his dream—“this long-winded project,” he called it—of creating a national meteorological service. If he’d survived another decade or so, he would have been around to see the invention that would revolutionize the field of meteorology and make his vision possible.

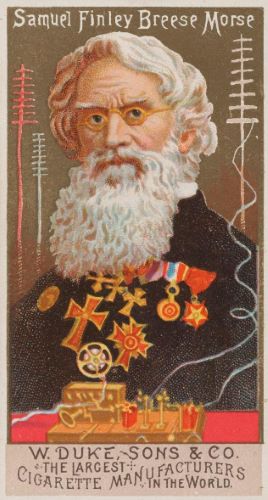

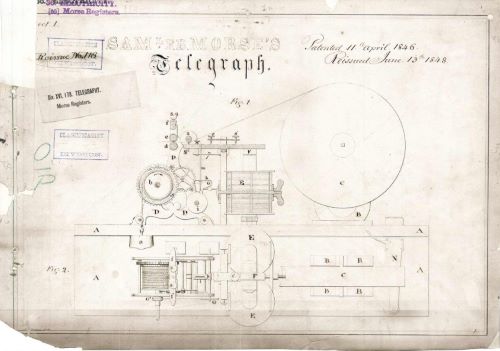

That invention was not a scientific tool, it was a communications device. And its inventor was not a scientist, but a painter. In 1837, Samuel F. B. Morse received a patent for his new “Electro Magnetic Telegraph,” which would astonish a crowd of onlookers at its debut seven years later in Baltimore. As the receiving operator decoded the message that had just flashed like magic across a wire from an office miles away in Washington, D.C., no one was thinking about what this incredible new device might mean for the weather. But newly employed telegraph operators with time on their hands quickly caught on. Jeptha Homer Wade, one of the founders of Western Union, would later recall:

I commenced operation in a telegraph office in 1846. With the small amount of commercial business then on the lines, the employees had less to do than they have now, and it was quite common for the operators in different parts of the country to enquire of each other about the weather, such as the direction and force of the wind as nearly as we could guess it, together with the temperature and its changes from time to time at different points. . . . I would frequently write upon the bulletin board in my office, what and when weather changes were coming. Frequently this was with such accuracy as to create considerable comment and wonder.

The operators had discovered something both interesting and paradoxical, the writer Andrew Blum observes in his book The Weather Machine. The telegraph had collapsed time but, in doing so, it had somehow simultaneously created more of it. Now people could see what the future held before it happened; they could know that a storm was on its way hours before the rain started falling or the clouds appeared in the sky. This new, real-time information also did something else, Blum points out. It allowed weather to be visualized as a system, transforming static, localized pieces of data into one large and ever-shifting whole.

Morse’s invention promised to finally help shed light on what Joseph Henry, the first secretary of the newly founded Smithsonian Institution, called in the 1847 annual report the “problem of American Storms.” Henry was referring to an ongoing scientific spat known as the “storm controversy,” which had been raging in the pages of journals for nearly two decades. The argument had arisen between William C. Redfield, a New York businessman, and a prominent meteorologist by the name of James Espy, and it centered on whether the motion of storms—hurricanes, blizzards, thunderstorms—in North America were rotational or centripetal in nature. This seemingly dry, theoretical debate had somehow blown up, generating a surprising amount of contention, ad hominem attacks, and national coverage as meteorologists in both the United States and Europe took sides, but definitive answers remained elusive. Now it seemed that American scientists were at a “peculiarly auspicious” moment to solve not just this but many more of the country’s perplexing weather-related mysteries, wrote Henry’s consultant, Elias Loomis. In presenting Henry’s proposal for a sweeping new meteorological project—a “grand meteorological crusade”—to the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, Loomis laid out the stakes in appropriately life-or-death terms:

If the laws of storms can be discovered, this knowledge must be of the highest importance to mankind, particularly to those who are employed in navigating the sea. If the prevalent character of a season can be anticipated, it would save the husbandman much bitter disappointment from the failure of his crops. If the influence of climate upon disease could be detected, it might add years to mean duration of human life.

The Smithsonian’s weather “crusade” would become the institution’s first major scientific undertaking, and it consisted of two parts. The first involved recruiting the telegraph companies to provide daily, nationwide weather updates. Starting in 1849, instruments were sent out to several offices around the country with a request that operators pause traffic on the lines in the morning to submit brief descriptions of local conditions. A few years later, Henry installed a map in the lobby of the Smithsonian Castle, where the collected information was displayed using a series of color-coded cards and arrows. Any time after 10:00 a.m., members of the public could stroll in and see for the first time “one view of the meteorological condition of the atmosphere over the whole country.”

Published newspaper reports would eventually follow. On May 7, 1857, the Washington Evening Star used the Smithsonian’s data to print what is considered to be the first weather forecast in the United States—although contemporary readers might have trouble recognizing it as one. (“Yesterday, there was a severe storm south of Macon, Ga;” the report read before going on to hedge its bets: “But from the fact that it is still clear this morning at that place and at Wheeling, it is probable that the storm was of local character.”)

The second and more ambitious part of Henry’s project involved a nineteenth-century version of crowdsourcing. The Smithsonian sent out calibrated instruments to 150 volunteer observers around the United States along with forms, which participants were asked to complete and mail back to Washington each month. Volunteers were instructed to record estimates, three times a day, of wind speed and direction and to note the type and number of clouds along with details of any precipitation. They were also to log any “casual phenomena,” a catchall term that included, but was not limited to, thunderstorms, tornadoes, aurora borealis, meteors, frosts, the temperatures of wells, and earthquakes.

The project caught on, and its popularity surged, with demand outstripping the agency’s ability to supply equipment. (Sending fragile instruments through the mail proved to be a challenge.) A decade later, reports were coming in from more than 600 individual volunteers, some from as far away as California, Canada, and the Caribbean. Observers included a flour merchant, a Mormon elder, a state senator from Florida, and a surveyor’s daughter, whose family would go on to participate in the project for 20 years. No scientific expertise was required. “Perseverance was valued more than profound thought, cooperation more than creativity,” the weather historian James Rodger Fleming observed. Tracking the weather became a democratic exercise, one that bound together its participants by emphasizing the “participation and contribution of the ‘common man.’” At least one meteorologist complained about illegible handwriting and inconsistent data collection practices on the forms they received, but the project was a success. The institution was inundated with information, enough to keep scientists knee-deep in data to analyze for years to come.

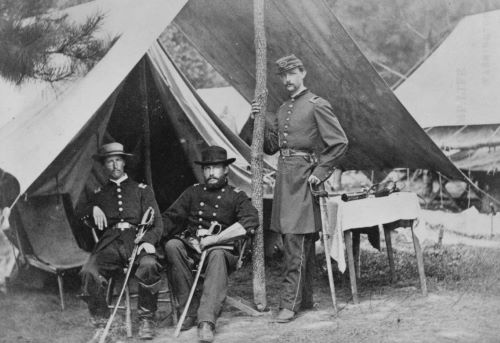

The American storm problem was successfully, and somewhat anticlimactically, put to bed in 1856 by a scientist named William Ferrel who would use mathematical equations to determine that storm movements were driven by rotation caused by the earth’s spin and by centripetal force. (Neither Redfield nor Espy had been entirely right, it turned out, and neither had been entirely wrong.) Ferrel’s discovery marked the end of the great storm controversy, but other divisions—political rather than meteorological—were about to impede the progress of weather science in the United States. As the Civil War got underway, the U.S. government slashed the Smithsonian’s requested budget. Volunteer observers stopped observing and went off to fight. Meteorological equipment was destroyed. Volunteers in Confederate states were unable to use the Union’s postal service to mail in their monthly logs. Science had been subsumed by more existential concerns. In the summer of 1862, while British meteorologists James Glaisher and Henry Coxwell were embarking on a series of scientific balloon expeditions that would take them an astonishing seven miles up into the atmosphere, American forces were slugging it out on the ground in the battlefield.

The Smithsonian’s volunteer weather project would not officially end until 1874, but after the war, Henry continued to face significant funding constraints, as well as larger questions about who should be tracking weather in the United States and how they should be doing it. Science was shifting toward professionalization in the post–Civil War era, and an era of amateur meteorologists—of statesmen tinkering with hygrometers in the fields of their plantations, of businessmen arguing about the atmosphere in scientific journals—was coming to an end.

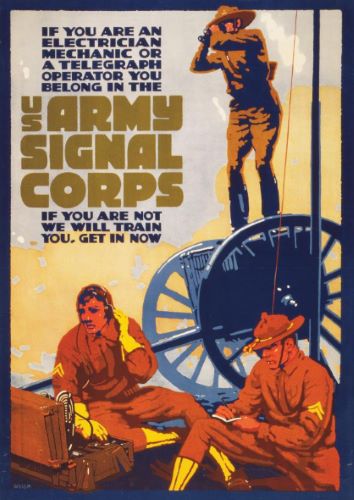

The country did need weathermen, however. That much was now apparent. And those weathermen had to come from someplace. Congressman Halbert E. Paine, a Republican from Wisconsin’s first district, thought that place should be the War Department. In 1869, he introduced a piece of legislation to that effect. “Military discipline,” he wrote, “would probably help secure the greatest promptness, regularity, and accuracy in the required observations.”

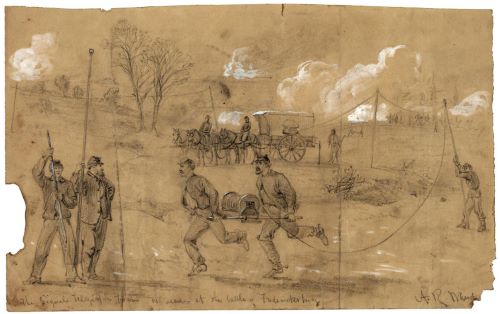

Paine’s bill caught the attention of Army officer Albert J. Myer, who saw in it a much-needed opportunity. Myer was the chief of a small and rather obscure bureau known as the Signal Corps, which had overseen communications and information systems for Union forces but was now languishing without a clear mission. With the war over, Congress had cut the Signal Corps’s requested budget in half; Corps men were being forced to practice their signaling exercises with salvaged materials in the abandoned Forts Whipple and Greble. A former military surgeon, Myer had only rudimentary training in weather observation, but he did understand telegraphy, and he knew a win-win situation when he saw one. A military weather service would provide a way to keep Myer’s bureau alive by providing him with a new “peacetime enemy worthy of his signals,” writes Fleming. And, Myer told Paine, the Signal Corps would be perfectly suited to the business of collecting and transmitting intel regarding storms. His lobbying efforts were successful. On February 9, 1870, Myer’s friend President Ulysses S. Grant signed the legislation, and a month later the U.S. Signal Corps was formally put on weather duty.

After saddling the nation’s first weather bureau with its extremely bureaucratic-sounding title—Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce—Myer moved swiftly to staff it. In the summer of 1870, the first class of newly enlisted privates reported for duty at Fort Whipple, which had been repurposed as the newly established Signal School. There, soldiers underwent a basic training regimen that consisted not only of military drills and signaling practice, but intensive scientific instruction with readings from Alexander Buchan’s Handy Book of Meteorology, Loomis’s Treatise on Meteorology, and studies of daily weather maps. (After additional field service, training, and examinations, privates could then qualify as “observer-sergeants.”) The program was rigorous, and included all the military trappings that Paine could have hoped for, with its recruits’ routines strictly scheduled from the first morning reveille to bedtime—a “strong contrast,” one graduate later remarked, “with my easy-going life at Harvard the previous four years.”

That regimented training was intended to prepare new observers for the postings they would receive upon graduation from the signal training school. Strict attention to detail was essential when it came to collecting data on local conditions and submitting it to the Signal Corps’s Washington, D.C., headquarters multiple times a day. Timing was crucial as soldiers around the country attempted to synchronize their observations as closely as possible. Additional paperwork was required for mandated monthly reports. Life at a Signal office field station was rarely dull, says Gary K. Grice, in his history of the National Weather Service. It was dangerous, though, and not only because inclement weather could, and did, inflict occasional casualties. For observer-sergeants, “other duties as assigned” could include dealing with labor riots, conflicts with Native Americans, outbreaks of yellow fever, fires, or other, stranger, tasks, as a memo sent out during a grasshopper plague in May 1877 makes clear:

SERGEANT: Should the Rocky Mountain locust appear at or near your station at any time during the present year, you will obtain all the information possible relative to the following subjects, viz:

The date of appearance of the locusts; the direction from which they came; the direction and velocity of wind and character of weather at time of appearance; the length of time they remain in your neighborhood, and amount of damage done by them; the direction and velocity of flight; direction of flight when they leave your station; whether they fly with or against the wind; whether or not they laid eggs in great quantities in the surrounding country; what means were taken to destroy the eggs or the locusts; any other information you can obtain on this subject. Should the locusts have arrived at your station previous to the receipt of this communication, you will obtain all the information possible from the citizens residing near you and forward it without delay to this office.

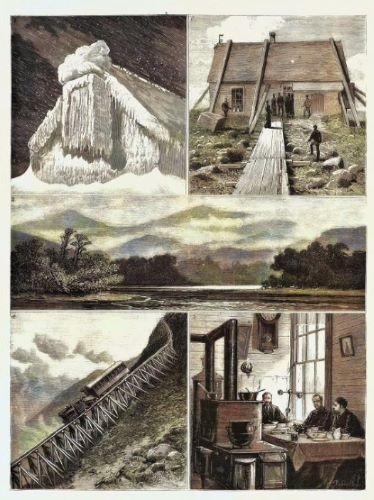

Signal stations were manned by one officer for the most part. In conditions that were frequently harsh or isolated, or both, military discipline sometimes failed. After examining submitted reports, one lieutenant discovered that some observers “were so confident of their ability to successfully counterfeit the laws of nature that they wrote up their observations several hours before or after the schedule time.” The military historian Rebecca Robbins Raines reports that another officer in Colorado fabricated his reports entirely, “believing that the authorities in Washington would not know any better.” One former Signal Corps officer recounted a story of an observer-sergeant who pawned off his meteorological equipment to pay his gambling debts—a dereliction of duty that came to light only when a Signal Office inspector arrived on-site unannounced to discover the field station abandoned and the sergeant working out of the pawnshop where his instruments had been relocated.

Such stories appear to be exceptions, however, in what was otherwise an impressive implementation, thanks primarily to the efforts of Myer. The Signal Office worked “around the clock,” says Raines. Over the course of a decade, the number of Signal stations grew from 24 to 110 as Signal Corps lines crept westward from the eastern seaboard and into the frontier states of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Civilian meteorological experts including Cleveland Abbe—the country’s foremost weather scientist—were brought on to serve as scientific advisors. Contacts were established at foreign weather bureaus. As the Signal Corps grew, the focus on tracking storms expanded to incorporate forecasts (which were referred to as “probabilities.”) Daily weather maps and bulletins produced by the Signal Office were displayed in post offices and observer-sergeants submitted their information to local newspapers. The work of the Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce was no longer benefiting just commercial interests—ranchers and sailors and farmers—but the public at large. At least one-third of households in the United States, Myer estimated at one point, were receiving weather information from the Signal Corps in one form or another.

By 1880, the Army’s weather service was “flourishing,” writes Raines. The state of the country’s military communications systems, however, was another story. The man-hours and money being siphoned away from the Army’s signaling work and into its storm intelligence efforts only continued following Myer’s death from nephritis in August of that year. The new chief signal officer, Colonel William B. Hazen, would go on to pour more of his office’s resources into weather-related research, rolling out new scientific projects—the development of a meteorology textbook, “aerial investigations” conducted in hot-air balloons, studies of atmospheric electricity—taking the Signal Corps’s meteorological work to new heights, literally, while the Division of Military Signaling tried and failed to catch up with the technological advances being made by its European counterparts.

In 1887, writes Raines, “the question of the status of the Signal Corps . . . finally came to a head” when Secretary of War William C. Endicott “stated in his annual report that because of its concentration on weather duties the Signal Corps could no longer be relied upon for military signaling.” Two years later, President Benjamin Harrison put an end to the Signal Corps’s weather service, calling for the program to be transferred out of the War Department and under the Department of Agriculture, where it would remain for another half century until it was transferred once again to its current home under the Department of Commerce.

As the Army’s weather service closed up shop, its observer-sergeants were offered two options: They could either stay on as enlisted men with the Signal Corps, or they could accept a discharge and continue their work as civilians at the Department of Agriculture’s new Weather Bureau. Almost all of them chose the latter. Their pioneering work and the achievements of the Signal Corps should not be discounted or overlooked, says Raines. The men who had once studied the skies above their lonely field stations, the ones who had dutifully tapped out their coded dispatches over telegraph lines had, without realizing it, laid the groundwork for a new and unimaginable era of meteorology and a future multi-billion-dollar government agency equipped with radar, geostationary satellites, and climate models devised by supercomputers. We now possess the kind of data that nineteenth-century meteorologists could only have dreamed of.

Still, those long-gone scientists most likely would appreciate how much the essential language of our forecasts—probabilities—remains the same. Uncertainty is the only certain thing about weather, after all, and the challenge of understanding what it holds in store for us continues.

Originally published to the public domain by Humanities, the Magazine of the NEH 44:4 (Fall 2023).