The speaking head offered a framework for imagining how far human ingenuity might extend into realms typically reserved for divine or supernatural authority.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

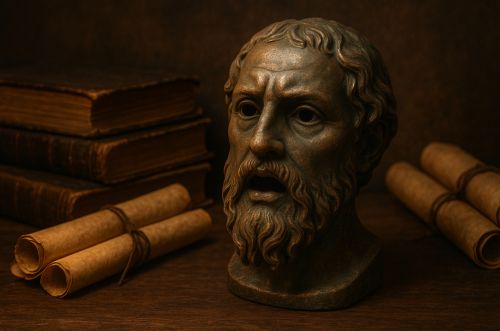

Legends of the “brazen head” occupy a distinctive position in the intellectual and imaginative landscape of the Middle Ages and early modern period. The stories depict a speaking automaton made of brass or bronze, constructed by a learned philosopher or cleric who seeks to extract prophetic knowledge from an artificial device. These accounts do not describe mechanical achievements in the modern sense but instead use the notion of artificial speech to explore anxieties about forbidden arts, technological ingenuity, and the boundaries of human inquiry. The idea of a fabricated head that could speak, answer questions, or foretell the future offered medieval writers a means of interrogating the nature of wisdom, the legitimacy of certain kinds of knowledge, and the moral risks believed to accompany intellectual ambition.1

The earliest forms of the legend in Europe appear in narratives surrounding Gerbert of Aurillac, later Pope Sylvester II, whose career became entangled with suspicions of Arabic learning and occult expertise. Medieval chroniclers such as Adémar of Chabannes described Gerbert’s encounters with mathematical, astronomical, and mechanical knowledge in Muslim Spain, framing these achievements within a polemical discourse about sorcery and illicit arts.2 Later medieval and Renaissance writers expanded these associations by attaching a speaking brass head to other prominent scholars, most notably Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus. The persistence of the motif across several centuries indicates the power of the brazen head as a symbol for interrogating the origins and consequences of exceptional intellectual capability, especially when that capability appeared to surpass accepted religious or philosophical boundaries.3

In English literary traditions, the brazen head becomes a dramatic emblem of the fraught relationship between natural philosophy and magic. Roger Bacon’s legendary automaton appears in chronicles, romances, and Renaissance drama, where the device’s construction, operation, and failure articulate concerns about mastery over nature. Works such as Robert Greene’s Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay emphasize the tension between aspiration and limitation, portraying the moment when the head delivers a cryptic message that the scholars fail to hear.4 This narrative pattern reflects broader cultural uncertainties about the pursuit of knowledge that seemed to approach or exceed divine prerogative. The head’s inability to provide the clarity that its creators demand reveals an enduring theme in medieval and early modern thought: that the quest for total understanding is inherently unstable and potentially perilous.

Across these varied accounts, the brazen head functions less as a description of a real mechanical device and more as a conceptual instrument for expressing ambivalence about the sources and consequences of knowledge. In monastic chronicles, scholastic treatises, and secular literature, the speaking head embodies conflicts between natural philosophy and theology, empirical curiosity and moral restraint, mechanical possibility and supernatural suspicion.5

What follows examines the legend’s historical development from its earliest medieval associations through its literary flourishing in England and its eventual transformation in early modern scientific culture. By tracing these shifting interpretations, it illuminates how the brazen head served as a symbolic site where medieval and early modern thinkers confronted the limits of human inquiry and the imagined potential of artificial intelligence long before such concepts acquired technological form.

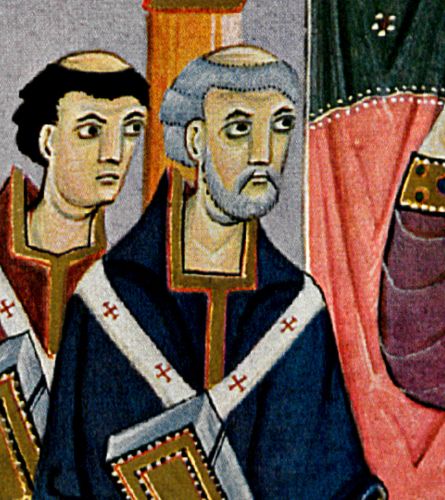

Gerbert of Aurillac and Early Medieval Origins of the brazen head Legend

The earliest Western narratives that resemble the later brazen head legend emerge from the reputation of Gerbert of Aurillac, the tenth-century scholar who became Pope Sylvester II in 999. Medieval chroniclers portrayed Gerbert as a figure whose intellectual accomplishments, particularly in astronomy, mathematics, and mechanical arts, were so extraordinary that they invited suspicion. Adémar of Chabannes, writing in the eleventh century, accused Gerbert of acquiring forbidden knowledge in al-Andalus, an allegation that reflected broader Christian anxieties about learning transmitted from the Islamic world.6 Although Adémar does not describe a speaking head, his portrayal of Gerbert’s engagement with instruments, automata, and advanced calculation forms the foundation upon which later writers constructed the image of a prophetic device.

The association between Gerbert and mechanical marvels grew in subsequent centuries as his biography became increasingly mythologized. William of Malmesbury, writing in the twelfth century, reported that Gerbert crafted mechanical organs and astronomical instruments of unusual sophistication.7 Surveys of medieval scientific folklore note that by the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Gerbert had become a symbolic figure representing both the promise and the danger of advanced knowledge.8 This evolving reputation paved the way for later storytellers to attribute to him an artificial speaking head, since he had already been framed as a scholar whose mastery of mathematical devices exceeded what many believed natural or permissible.

By the high Middle Ages, traditions linking Gerbert to oracular mechanisms placed him within a broader cultural discourse that blurred distinctions between natural philosophy and illicit arts. The idea that Gerbert possessed a device capable of answering questions or foretelling events appears in several later chronicles and exempla literature, often presented as evidence of his supposed pact with demonic forces.9 These accounts do not describe the artifact’s construction in any technical detail. Instead, the object functions narratively as a sign that Gerbert’s intellectual achievements derived from morally ambivalent sources. The device’s imagined capacity for artificial speech symbolized anxieties that certain forms of learning, particularly those transmitted across cultural boundaries, might grant access to knowledge reserved for divine authority.

The Gerbert tradition established narrative structures that later became central to the brazen head motif: a learned figure constructs an artificial device, the device speaks or prophesies, and the scholar’s ambition is framed as transgressive. This early form of the legend demonstrates how medieval writers used technological imagination to negotiate concerns about cross-cultural knowledge, ecclesiastical authority, and the limits of human inquiry.10 Although later figures such as Roger Bacon would become more closely associated with the brazen head, the fundamental tension articulated in the Gerbert stories endured: the fear that extraordinary intellectual capability might exceed proper moral and theological bounds.

Roger Bacon and the English Reinvention of the Brazen Head

By the fourteenth century, the brazen head legend had migrated into English literary culture, where it became firmly attached to the figure of Roger Bacon. Although there is no evidence that Bacon constructed any mechanical device resembling such an automaton, later medieval authors framed him as a scholar whose experimental interests and engagement with optics made him an ideal subject for stories about artificial speech.¹¹ John Gower’s Confessio Amantis positions Bacon within a lineage of learned men credited with magical or mechanical wonders, revealing how literary imagination increasingly associated complex technical knowledge with the possibility of fabricating devices that could speak or prophesy.¹² These portrayals emphasized the ambiguity of Bacon’s intellectual reputation, situating him between legitimate natural philosophy and the shadowed realm of forbidden arts.

As English writers elaborated the legend, the brazen head evolved into a narrative instrument that expressed cultural tensions surrounding scientific curiosity. In the later Middle Ages, Bacon was imagined to have constructed a prophetic head capable of delivering knowledge in a single utterance. The exact content of this utterance varied across manuscripts, but the motif of a fleeting or enigmatic message became central to the story’s moral implications.¹³ The device’s momentary speech functioned as a narrative test of Bacon’s mastery over nature. When the scholar failed to grasp the prophecy, writers presented the failure as evidence that even extraordinary learning could not overcome the inherent limits of human perception or divine authority.

The most influential treatment of the legend appeared in Robert Greene’s 1594 play Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, where the brazen head receives its fullest dramatic elaboration. Greene portrays Bacon as a scholar driven by ambition, intent on creating a device that will secure England’s military security and intellectual supremacy. When the head finally speaks, uttering the sequence “Time is,” “Time was,” and “Time is past,” Bacon misses each warning.¹⁴ Greene’s version cemented the motif of prophetic failure as a defining feature of the legend. The automaton’s cryptic utterances became a dramatic symbol of the scholar’s overreaching desire to command knowledge beyond mortal reach.

Greene’s adaptation also reveals how the brazen head functioned within a broader Renaissance discourse that questioned the moral status of emerging natural philosophies. Even as sixteenth-century writers celebrated ingenuity, they continued to frame certain kinds of knowledge as potentially dangerous when pursued without humility or restraint. Scholars have shown that Renaissance discussions of learned magic frequently placed figures like Bacon at the boundary between licit and illicit arts, a position reinforced by literary depictions of devices that appeared to transcend natural causes.¹⁵ The brazen head thus operated as an emblem through which writers explored anxieties about the expanding scope of human artifice at a moment when natural philosophy was being reshaped by new methods and technologies.

By the early modern period, the association between Roger Bacon and the brazen head had become so widespread that it overshadowed earlier continental versions of the legend. Bacon’s reputation as an experimental philosopher, combined with the moralizing structure of English drama, allowed authors to present the brazen head as both a marvel and a cautionary sign.¹⁶ The endurance of this association suggests that English audiences found in Bacon a compelling figure through whom to contemplate the risks of intellectual ambition. The device’s capacity to speak briefly before collapsing transformed it into a symbol of the precarious balance between inventive brilliance and the inevitable boundaries of human knowledge.

Albertus Magnus, Scholastic Technology, and the Philosophical Automaton

Legends connecting Albertus Magnus to mechanical marvels circulated widely in the later Middle Ages, and these accounts helped expand the conceptual field in which the brazen head was imagined. Although no medieval text claims that Albertus constructed a speaking head specifically, several narrative traditions attribute to him the creation of lifelike automata that blurred the boundary between natural philosophy and artificial life. One of the most widely cited anecdotes appears in later commentaries on Thomas Aquinas, which recount that Aquinas destroyed a mechanical figure in Albertus’s study because he believed it to be an ensouled creature.17 This anecdote, though transmitted centuries after the events it purports to describe, reflects a longstanding effort to frame Albertus as a scholar capable of producing devices whose sophistication challenged ordinary distinctions between artifice and nature.

The circulation of such stories was reinforced by Albertus’s historical reputation for investigating the principles of motion, matter, and perception. Modern scholarship documents how medieval readers interpreted Albertus’s scientific writings as evidence of exceptional technical capability.18 His commentaries on Aristotle’s De anima and Physics offered systematic explanations of causation, sensation, and animation, which later authors recast as evidence that he possessed knowledge enabling him to fabricate artificial beings. Although these commentaries do not describe mechanisms or automata, their theoretical emphasis on natural causes created a conceptual space in which the fabrication of mechanical figures could be imagined as an extension of legitimate inquiry rather than an act of sorcery.

The association between Albertus and artificial life was strengthened by hagiographic texts that portrayed him as a scholar whose mastery of natural philosophy verged on the miraculous. Later retellings described automata capable of responding to human presence or performing limited actions, stories that appear in early modern compilations of marvels.19 These narratives often lacked technical detail, but their persistence suggests that medieval and Renaissance audiences found the idea of an artificial servant or guardian compatible with Albertus’s intellectual stature. While these accounts do not feature a brazen head, they contributed to a cultural environment in which speaking or responsive mechanisms were attributed to figures associated with advanced learning.

The Albertus tradition is essential for understanding how scholastic thought shaped the later reception of the brazen head. By linking mechanical marvels to a theologian renowned for his rigorous approach to natural causes, medieval writers framed the possibility of constructing artificial figures within a philosophical context rather than limiting it to magical speculation.20 The notion that Albertus’s work approached the threshold between licit natural philosophy and illicit creation provided later authors with a model for portraying scholars like Roger Bacon. Through these narratives, the brazen head became connected not only to fears of forbidden knowledge but also to the intellectual aspirations that animated scholastic inquiry, revealing how medieval thought could accommodate the idea of artificial life as both a symbol and a theoretical possibility.

Technology, Magic, and Artificial Speech: Intellectual Frameworks Surrounding the Brazen Head

Medieval and early modern imaginings of artificial speech drew upon philosophical traditions that attempted to explain how motion, sound, and perception operated within the natural world. Aristotelian natural philosophy, which dominated university curricula, provided conceptual tools for thinking about the animation of bodies and the production of sound through natural causes. Scholars such as Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas interpreted Aristotle’s writings on pneuma, motion, and sensation in ways that later readers understood as describing the conditions under which a crafted device might appear to act or speak.21 These interpretations did not claim that mechanical speech was achievable. Instead, they offered a framework that made the idea theoretically comprehensible, thereby enabling storytellers to imagine the brazen head as an artifact situated within natural processes rather than outside them.

At the same time, learned magic traditions circulated texts that described artificial beings or mechanisms capable of producing signs, warnings, or speech. Works attributed to the Hermetic corpus and compilations such as the Liber Vaccae, translated into Latin from Arabic sources, contained recipes for creating images or figures that would answer questions or reveal hidden information.22 Although these texts are highly symbolic and do not describe actual technology, scholars have shown that they shaped medieval beliefs about the possibility of constructing devices that functioned as intermediaries between human and spiritual realms. The brazen head, in this context, became a narrative embodiment of the capacity of ritual knowledge to animate matter through the manipulation of natural and celestial forces.

The boundary between natural philosophy and magic was further complicated by scholastic debates about causation. Theologians distinguished carefully between natural, preternatural, and supernatural operations, with demonic agency occupying an ambiguous category that could account for phenomena appearing to transcend human artifice.23 Research demonstrates that medieval audiences often interpreted extraordinary devices through a causal hierarchy that included natural mechanisms, astrological influences, and malevolent or benevolent spirits.24 This intellectual environment made it possible to imagine an artifact that spoke not because it possessed machinery capable of generating sound, but because it served as a material conduit for forces situated beyond ordinary perception.

Technological knowledge also shaped perceptions of what artificial devices could accomplish. Mechanical innovations such as water clocks, astronomical instruments, and self-moving figures described by authors including Hero of Alexandria circulated in manuscripts available to medieval scholars.25 Although the technical sophistication of these devices was often misunderstood, their existence attested to the possibility of machines that performed tasks automatically. Hero’s treatises on pneumatics and automatism, widely copied and excerpted in the medieval period, provided concrete examples of devices that could move or respond to stimuli without direct human intervention. The presence of such material contributed to an intellectual climate in which stories about a speaking head, however exaggerated, appeared consistent with the outer limits of technological possibility.

These intersecting traditions influenced literary representations of the brazen head by offering plausible conceptual structures for imagining artificial speech. Writers drew upon natural philosophy to ground the device within recognizable theories of motion and sound, while magical texts supplied a symbolic vocabulary for discussing artificial life. The brazen head therefore did not function merely as a fictional marvel but as an embodiment of contemporary attempts to understand the relationship between natural forces and human ingenuity.26 It occupied a space where intellectual speculation, mechanical knowledge, and theological reflection converged, revealing how artificial speech served as a metaphor for the expansion and potential transgression of human inquiry.

By situating the brazen head within these intellectual frameworks, medieval and early modern narratives reveal that its power lay not only in the idea of a speaking machine but in the uncertainties that surrounded the sources of its speech. Whether readers interpreted the device through natural, magical, or spiritual causation, the brazen head represented a point of tension where explanations of the world competed and overlapped.27 Its imagined utterances forced audiences to confront the limits of human mastery over knowledge, illustrating how a seemingly impossible artifact could become a vehicle for exploring the deepest questions of epistemology and moral responsibility.

Literary Uses of the Brazen Head: Prophecy, Tragedy, and the Failure of Human Control

Medieval and early modern writers used the brazen head as a narrative device through which to explore the dangers of intellectual ambition and the instability of prophetic knowledge. In English literature, the motif became especially prominent as authors adapted earlier folkloric and scholarly traditions into moral narratives. The clearest example appears in Greene’s Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, where the brazen head delivers its enigmatic sequence of utterances while its creators fail to attend.28 Greene’s dramatization crystallized several long-standing themes: the peril of heedlessness, the fleeting nature of prophetic insight, and the inability of human mastery to overcome the constraints imposed by time and divine authority. The head’s collapse immediately after speaking serves as a reminder that knowledge pursued without discipline or humility ultimately eludes control.

Earlier literary treatments set the stage for Greene’s version by establishing the brazen head as a symbol of contested knowledge. Gower’s Confessio Amantis references Roger Bacon within a catalogue of learned men associated with miraculous or ambiguous arts.29 Although Gower does not describe a speaking head, his placement of Bacon among practitioners of extraordinary knowledge contributed to a cultural atmosphere in which the construction of such a device seemed compatible with his intellectual identity. These literary contexts framed the brazen head as an emblem of scholarly aspiration that risked crossing moral boundaries, especially when directed toward the acquisition of prophetic or esoteric insight.

Broadside ballads and chapbooks circulating in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries extended the motif into popular print culture. These works frequently retold the story of the brazen head in abbreviated forms that emphasized moral exhortation or simple entertainment.30 In such versions, the device often functioned as a warning against neglecting divine will or against pride in human craftsmanship. By presenting the head as a marvel whose usefulness is nullified by human error, printers and authors reinforced the notion that technological ingenuity, when divorced from humility, could not guarantee access to reliable knowledge. The brazen head thus became a flexible symbol capable of addressing the anxieties of diverse audiences, from learned readers to theatergoers and broadside consumers.

Literary uses of the brazen head consistently deployed the device to probe the limits of human agency. Scholars in these narratives often sought to command forces that exceeded their grasp, only to encounter the constraints of time, fate, or divine authority.31 By dramatizing the moment when the brazen head speaks but fails to offer practical guidance, authors transformed the device into a metaphor for the ambition to achieve perfect understanding. The motif’s endurance across genres reflects its ability to express concerns about intellectual overreach, the ethics of inquiry, and the unpredictable consequences of attempting to control knowledge that resists human governance.

Early Modern Science, Mechanism, and the Decline of the Brazen Head

By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, shifting understandings of natural philosophy increasingly shaped how audiences evaluated stories of mechanical marvels. As European scholars refined mechanical principles and experimented with automata, the idea of a speaking device began to move from the realm of sorcery into one of theoretical possibility, even if still improbable. Writers such as Giovanni Battista della Porta, whose Magia Naturalis sought to distinguish natural magic from demonic intervention, discussed optical and acoustic effects that could produce illusions of speech.32 Although della Porta does not describe a brazen head, his efforts to rationalize extraordinary phenomena reflected a cultural climate in which mechanical explanations became increasingly viable alternatives to supernatural accounts.

Mechanical innovation further reshaped expectations surrounding artificial devices. Automata created by Renaissance engineers, including the moving figures attributed to Hans Schlottheim and the sophisticated astronomical machines built by clockmakers in Nuremberg and Augsburg, demonstrated that complex mechanical systems could imitate life or motion.33 Marin Mersenne’s writings on acoustics explored how sound could be generated and transmitted through pipes, cavities, or resonant chambers, providing theoretical insight into artificial voice production.34 These advances did not confirm the possibility of an actual speaking head, but they made the concept more intelligible within emerging scientific paradigms. The brazen head therefore lost some of its purely magical associations as mechanical knowledge expanded.

The rise of empirical science also influenced how intellectuals evaluated earlier tales of marvels. Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum promoted methods grounded in observation and experimentation, urging scholars to avoid uncritical acceptance of legendary accounts.35 Within this context, the brazen head became an illustrative example of earlier credulity or imaginative excess. While the device continued to appear in popular prints and theatrical works, learned discourse increasingly framed it as a story rooted in symbolic rather than literal truth. The divergence between popular and scholarly treatments reveals a period of transition in which older magical motifs persisted even as intellectuals began redefining the boundaries of legitimate inquiry.

Despite the growing prominence of mechanical philosophy, associations between artificial speech and demonic causation did not vanish entirely. Theologians continued to caution that certain forms of knowledge or experimentation might invite spiritual danger, particularly when they involved attempts to manipulate natural forces in unprecedented ways.36 This caution helped preserve the moral themes embedded in earlier versions of the brazen head legend. The device remained a means of contemplating the ethical dimensions of technological ambition, even as the mechanisms underlying artificial motion or sound became better understood. The oscillation between mechanical possibility and moral concern reveals the complexities of early modern thought, which rarely embraced technological innovation without reservation.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the brazen head had largely receded from serious philosophical speculation, surviving most prominently in literature, chapbooks, and antiquarian accounts.37 Its decline in learned discourse reflected broader transformations in scientific methodology and epistemology. As natural philosophy developed more rigorous standards for evaluating evidence, legends rooted in ambiguity or allegory no longer aligned with scholarly expectations. Yet the persistence of the brazen head in popular culture indicates that the legend continued to satisfy a fascination with artificial intelligence, prophecy, and the consequences of human overreach. Its shifting reception demonstrates how intellectual and technological developments can transform, but not entirely erase, powerful narrative symbols.

Conclusion: The brazen head and the Boundaries of Human Knowledge

Across the medieval and early modern periods, the brazen head persisted as a symbolic artifact through which writers, theologians, and philosophers contemplated the limits of human inquiry. Whether associated with Gerbert of Aurillac, Roger Bacon, or Albertus Magnus, the speaking head offered a framework for imagining how far human ingenuity might extend into realms typically reserved for divine or supernatural authority. The device’s capacity for momentary or enigmatic speech highlighted tensions surrounding experimental knowledge and the dangers attributed to overreaching intellect. The legend therefore functioned as a conceptual tool through which medieval and early modern thinkers expressed concerns about ambition, morality, and the fragile relationship between wisdom and hubris.38

The intellectual history underlying the brazen head demonstrates how narratives of artificial speech emerged from overlapping traditions of natural philosophy, learned magic, and technological curiosity. Aristotelian theories of motion and sensation allowed authors to speculate about the conditions under which matter could appear animated, while magical texts supplied symbolic frameworks for envisioning devices that responded to celestial or spiritual influences.39 As mechanical knowledge expanded, the possibility of constructing automated or responsive figures became more plausible, even if still limited. These intellectual currents produced a layered understanding of the brazen head, one that encompassed philosophical speculation, literary allegory, and theological caution.

The legend’s endurance also reflects its adaptability across social and intellectual contexts. In elite literary circles, the brazen head expressed anxieties about the legitimacy of new forms of knowledge and the potential consequences of experimental method. In popular culture, broadside ballads and chapbooks transformed the device into a moralizing spectacle that warned against pride or inattentiveness.40 These divergent interpretations demonstrate the narrative flexibility of the motif, which could accommodate scholarly debate, religious instruction, or theatrical entertainment. The brazen head thus served as a meeting point for cultural conversations about authority, innovation, and the uncertain nature of prophecy.

By tracing the evolution of the brazen head across centuries, it becomes clear that the legend’s significance lies not in whether such a device could exist, but in how its imagined properties illuminated shifting conceptions of human knowledge. The stories reveal a sustained effort to negotiate the boundaries between natural forces and human artifice, between legitimate inquiry and forbidden arts.41 The brazen head’s brief, cryptic speech encapsulated the enduring fear that insight pursued without restraint would ultimately fail to provide clarity. Its history therefore offers a window into the intellectual landscapes of the medieval and early modern periods, where material imagination and philosophical reflection converged in efforts to understand the limits of perception and the allure of artificial intelligence long before its technological realization.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Lynn Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1923), 678–689.

- Adémar of Chabannes, Chronicon, ed. Pascale Bourgain (Turnhout: Brepols, 1999), 148–152.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 1, 689–694.

- Robert Greene, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, ed. Daniel Seltzer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), introduction and commentary.

- Edward Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 45–52.

- Adémar of Chabannes, Chronicon, 148–152.

- William of Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum, ed. and trans. R. A. B. Mynors, R. M. Thomson, and M. Winterbottom (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 1: 248–250.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 1, 678–689.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 1, 689–694.

- Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe, vol. 1, 45–52.

- John Gower, Confessio Amantis, ed. Russell A. Peck (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1980–2004), Book IV.

- Gower, Confessio Amantis, Book IV.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2, 256–259.

- Greene, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, introduction and commentary.

- Frank Klaassen, The Transformations of Magic: Illicit Learned Magic in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012), 112–118.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2, 259–264.

- Thomas Aquinas, Opera Omnia, vol. 25, ed. R. Busa (Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog, 1980), anecdotal commentary cited in relation to Albertus; discussed in Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe, 47.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2, 267–272.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2, 272–276.

- Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe, 47–49.

- Aristotle, De anima, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1: 641–692; Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Aristotle’s De anima, trans. Kenelm Foster and Silvester Humphries (Notre Dame: Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, 1994), selected passages.

- Klaassen, The Transformations of Magic, 84–91.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa contra Gentiles, trans. Anton C. Pegis (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1975), Book III.

- Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe, 45–52.

- Hero of Alexandria, Pneumatica, ed. and trans. Bennet Woodcroft (London: Taylor Walton and Maberly, 1851); Automata, in The Works of Hero of Alexandria, ed. and trans. T. L. Heath (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1899).

- Klaassen, The Transformations of Magic, 112–118.

- Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic, 49–53.

- Greene, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, introduction and commentary.

- Gower, Confessio Amantis, Book IV.

- Tessa Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 85–90.

- Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Science, vol. 2, 259–264.

- Giovanni Battista della Porta, Magia Naturalis (Naples: Salviani, 1589), Book XX.

- Jessica Riskin, The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 45–52.

- Marin Mersenne, Harmonie Universelle (Paris: Cramoisy, 1636), 1: 18–24.

- Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, ed. Lisa Jardine and Michael Silverthorne (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 36–39.

- Stuart Clark, Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 414–420.

- Clark, Thinking with Demons, 421–423.

- Bever, The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe, 49–53.

- Klaassen, The Transformations of Magic, 84–91.

- Watt, Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 85–90.

- Clark, Thinking with Demons, 414–420.

Bibliography

- Adémar of Chabannes. Chronicon. Edited by Pascale Bourgain. Turnhout: Brepols, 1999.

- Aristotle. De anima. In The Complete Works of Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes, vol. 1, 641–692. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Bacon, Francis. Novum Organum. Edited by Lisa Jardine and Michael Silverthorne. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Bever, Edward. The Realities of Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Clark, Stuart. Thinking with Demons: The Idea of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- della Porta, Giovanni Battista. Magia Naturalis. Naples: Salviani, 1589.

- Gower, John. Confessio Amantis. Edited by Russell A. Peck. 3 vols. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1980–2004.

- Greene, Robert. Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay. Edited by Daniel Seltzer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Hero of Alexandria. Automata. In The Works of Hero of Alexandria, edited and translated by T. L. Heath. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1899.

- ———. Pneumatica. Edited and translated by Bennet Woodcroft. London: Taylor Walton and Maberly, 1851.

- Klaassen, Frank. The Transformations of Magic: Illicit Learned Magic in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

- Malmesbury, William of. Gesta Regum Anglorum. Edited and translated by R. A. B. Mynors, R. M. Thomson, and M. Winterbottom. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

- Mersenne, Marin. Harmonie Universelle. Paris: Cramoisy, 1636.

- Peck, Russell A., ed. Confessio Amantis. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1980–2004. (Listed under Gower above; included here only once in the final bibliography.)

- Riskin, Jessica. The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Thorndike, Lynn. A History of Magic and Experimental Science. 2 vols. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923.

- Thomas Aquinas. Commentary on Aristotle’s De anima. Translated by Kenelm Foster and Silvester Humphries. Notre Dame: Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, 1994.

- ———. Opera Omnia. Vol. 25. Edited by R. Busa. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog, 1980.

- ———. Summa contra Gentiles. Translated by Anton C. Pegis. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1975.

- Watt, Tessa. Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Originally published by Brewminate, 12.08.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.