The emphasis was on the spiritual or supernatural means of self-protection.

By Dr. Jussi Hanska

Professor of History

Tampere University

Introduction

This book is not primarily concerned with the scientific or technological means of avoiding natural disasters, but a few words must be said about them. This is important because we need to emphasise the fact that even though medieval men generally attributed natural disasters to supernatural powers, they nevertheless were no more fatalistic in confrontation with them than we are.

Modern anthropologists generally agree, and it fits well with common sense, that premodern men as well as members of primitive cultures have always been bound to use all the technological and scientific knowledge available to them to protect themselves and understand the reasons and logic of cataclysms. On the part of primitive cultures this common sense rule has been observed and verified already by Bronislaw Malinowski.49 This is equally true for medieval man. If there were means of preventing disaster or limiting its damage, they were most rigorously used. One did not leave it to God alone to provide for water if it was possible to construct an irrigation system. One must not overestimate the technical abilities of medieval people, but it is equally dangerous to presume that they were ignorant in the field of technology and natural sciences.

According to the widely accepted theological opinion, nature was always friendly and submissive to man in those days when man still lived in the Paradise of Eden. Nature took care of his needs and obeyed him willingly. After the Fall, man had to face a new kind of nature, hostile and dangerous. Augustine writes in his De genesi that harmful plants exist only as a consequence of human sinfulness, not because of a perverse act of creation on God’s part. By committing the original sin, man had lost his control over nature.50

Augustine only speaks directly about the control over animals and plants, but his words can be applied mutatis mutandis to the whole of nature. Thus, according to this theological view, natural disasters entered the stage when man lost his control over nature. The ideal of man’s superiority over nature remained alive in Christian theology. The progeny of Adam was to restore that early perfection by hard labour and through the reshaping of his moral character.51

In this ideal, gaining control over natural phenomena through science and technology was a completely acceptable practice as long as it worked. If it failed it was a sign of man’s fallen state rather than a sign of his lacking technological knowledge. Thus it was completely acceptable to try to control nature. Success in doing so was perceived as an evident sign of inner virtuousness.

However, in practise there was not much one could do to prevent natural disasters. Effective means of protection against epidemics, for example, were extremely scarce. They were virtually non-existent before the Late Middle Ages, and even then they were mostly concerned with the plague. The first temporary health boards were set up in Italian towns during the Black Death. They normally were dissolved after the acute crisis situation was over. Only in 1486 was the first permanent health board, which was also concerned with preventive measures, founded in Venice. The rest of Europe was even less advanced in these matters.52

We may conclude that there certainly were scientific and technological measures taken to prevent natural disasters. Some of them might even have been limitedly useful. Nevertheless, throughout the whole of the Middle Ages the emphasis was on the spiritual or supernatural means of self-protection.

Religion vs. Magic

As we have seen, the possibilities for avoiding disasters or even helping the victims to survive were rather limited. When human means of protecting the community from the hostile forces of nature were found to be inadequate, the divine element entered. Supernatural assistance seemed to be the only alternative. Like so many other so-called primitive societies, pre-Christian Europeans tried to control nature by magical means. By magical, we mean practices, which disregarded natural causality, and anticipated positive results from man’s participation in the universe. Some of these practices survived the christianisation of Europe, for we find traces of them in medieval sources.

Aaron Gurevich has analysed these practices as they appear in early medieval penitentials. Magic rites were performed for numerous reasons: healing, love, and fertility of different sorts. The rites that are particularly interesting for us here are those performed at the Calends of January to secure good harvest for the coming year.53 The pagan rites and celebrations, which were meant to secure good harvest, had assimilated with the Christian practises.

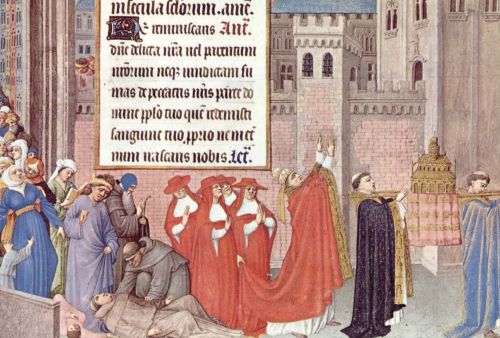

It is known that special processions in the time of natural disasters were organised as early as in the fourth century. Saint John Chrysostom mentions litanies held in April 399, when heavy rains were endangering the harvest. Similarly, Mamertus, bishop of Vienne, organised processions about the year 470 after an earthquake and lightning.54 The most famous early procession, however, was organised by Pope Pelagius II in November 589. The overflow of the Tiber had caused flooding in Rome. In turn, or so the contemporaries thought, this caused an outbreak of plague epidemic. Pelagius II ordered a general fast and procession. It turned out to be his last papal act, for he and seventy other people died of the plague in the middle of the procession. These processions were continued until the end of the epidemic by Gregory the Great, Pelagius’ successor on Saint Peter’s see.

According to medieval sources, it was Gregory the Great who ordered such processions to be organised throughout western Christendom, and thus they came to be known as Litania romana or Litania Gregoriana.55 The litanies of Gregory the Great were also known as greater litanies to distinguish them from earlier litanies instituted by the above-mentioned bishop Mamertus of Vienne. Gregory’s litanies were called major, because he was a pope, and they were first performed in the city of Rome, Mamertus’ litanies were called minor litanies, because he was merely a bishop and because they were first performed in the less important Christian centre of Vienne.

Major litanies were normally performed on the feast of Saint Mark’s Day (25th April) whereas the minor litanies were held on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday before Ascension Day. Rogation Day ceremonies retained their original penitential nature. Penance was supposed to make God look more favourably upon the supplications of his people. The specific liturgical form used on that day was the greater litany, a public penitential procession from one church to another, during which a litany of saints was sung.

On 25 April the pagan Romans used to hold a procession to honour the goddess Robigo. Prayers were offered to obtain her protection for the crops. The Christian Romans simply followed the old custom, only the forms of the rites and prayers were christianised or baptised as the scholars of late antiquity often say. The Church simply replaced old Roman ceremonies with the newly invented Christian processions. These took place in connection with saint Mark’s Day, but the function and the form of these processions had nothing to do with the apostle. They were essentially borrowed from the robigalia feast.56

Some later medieval writers thought that Gregory the Great instituted the Greater Litany during the great pestilence in Rome. Honorius Augustodunensis writes in his Gemma ecclesiae that the Greater Litany is read in Church once a year in order to ask God to protect the people and domestic animals from pestilence.57 Modern historians know from the writings of Gregory himself that in his time this practise was already well established.58 Nevertheless, during the Middle Ages and immediately after, the common idea was that Gregory invented the Greater Litany.59

This attribution gave the litania majora higher authority. In the course of the centuries the movement toward a uniform liturgical practise imposed litania majora processions on the whole of the West. The minor litanies invented by Mamertus, originally celebrated only in the Gallican church, were eventually accepted in the whole of western Christendom as well. They were adopted in Rome by order of Pope Leo III around the year 800. The ninth century also saw them adopted in Germany.60

The essential nature of Rogation processions is obvious even with a cursory look into surviving liturgical sources. They were a sort of bargain in which the community traded penitential activities and bowed before God for Divine protection and hope of a good year to come. André Vauchez has expressed doubts about the survival of the Greater Litany processions in urban surroundings. He proposed that Litanies were mostly celebrated in the countryside to obtain protection for crops, and even there the feast could sometimes have been confused with the feast of the Invention of the Holy Cross (May 3). It is known that in the post-medieval period masses were celebrated on that day to ward off storms and preserve the fruits of the earth.61 Irrespective of whether Vauchez’s hypothesis is valid or not, it remains clear that processions, masses and other protective liturgical ceremonies were celebrated in spring time to secure crops.

The pagan Roman rites of securing a good harvest, which were substituted by Rogation Days, were not of course followed in the whole Western Europe. Nevertheless, there was no lack of similar pagan rites that could be replaced. Different sorts of magic were also performed to avert storms and change the climate. The penitential of Burchard of Worms describes one such event. During a long lasting drought the women of German villages used to inspect a great number of young girls, strip one naked, and place her at the head of a procession walking out of the village. Once outside the girl would dig up a root of a certain herb, put it on her left foot, and return to the village walking backwards like a crab. Gurevich cites many other examples from Burchard’s penitential and concludes that ‘medieval villagers were not too far removed from such animistic people’.62

The Rogation Day processions and the case outlined by Burchard of Worms do not constitute the only existing examples of such superstitious or pagan survivals in medieval or even early modern Europe. Sometimes these old pagan beliefs were mixed with newer Christian doctrines to produce totally new ways of protecting communities and assuring good crops.63 It was the strategy of the early Church to absorb old pagan rites as much as possible into the new Christian religion. Gregory the Great emphasised that it was essential to be very cautious when destroying the remains of pagan cults. Sometimes it might be a good idea to burn idols, but in other cases better results could be achieved by reinforcing the old cults with a new Christian meaning.64

The eclectic nature of early medieval Christianity has raised the question: How Christian was Europe? This problem is relevant to this study because the central hypothesis of this book is that the Church had a central role in medieval ‘disaster management’. If one is to argue that the role of the Christian church was most important in helping people survive and understand natural disasters, one needs to be sure of the predominant role of the Church in shaping people’s mentalities.

Indeed, the significance of Christianity during the Middle Ages has been one of the crucial questions of medieval historiography. Some eminent French historians, most notably Jacques Le Goff and Jean-Claude Schmitt, have argued mostly on the basis of exempla material that there were two distinct medieval cultures; clerical and bookish Christian culture and a popular culture, subscribed to by the great majority of the people, which remained essentially pagan.65

These ethnologically oriented historians take the view that new Christian rituals and cults established on the old pagan sites were not really Christian. They were merely the same old pagan customs re-created with new names.The Catholic historian Jean Delumeau does not accept this idea. He states that historians ought to make a methodological distinction between direct relationships and similarities. It was not a question of old cults and beliefs with new names, but of new cults and beliefs with some familiar details and often-familiar geographical locations.

The American historian John van Engen argues that Le Goff’s and Schmitt’s idea of a semi-pagan medieval Europe filled with remnants of ‘Indo-European folklore’ is rather dogmatic and ahistorical. He concludes that:

‘Recent study of popular religious culture has forced historians to focus on its distinctive and sometimes non-Christian character and function. But any approach that denies the reality of Christianisation as crucial to the formation and flowering of medieval religious culture will miss wholly its inner dynamic.’66

Aside from the views and theories of French historians, there have been less controversial critics of the traditional concept of the Christian Middle Ages. According to František Graus, early medievalists took their model of medieval religiosity from the baroque, and thus committed a fundamental mistake. They were projecting their romantic notions of a lost golden age of Christianity on the past. In reality, Christian Europe was never as homogenous and religious as has been thought. Graus, however, does not even try to deny the importance of the Christian religion.67

We may conclude that by the end of the twelfth century medieval Europe was thoroughly christianised, save perhaps some remote areas in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe. When we speak of christianised Europe, we must, however, take into account that the Christianity of the common medieval peasant was very different from today’s Christianity, which emphasises personal religious experience.68

At the heart of medieval Christianity were rituals performed on a parochial level. They demanded attention, not necessarily personal belief. As Keith Thomas points out, these rituals could be interpreted not as symbolical acts, but as magical ones. He proposes that the concepts of magic (a kind of manipulation) and prayer (a form of supplication) were often confused in the minds of ordinary Christians. Thomas concludes that the line between magic and religion is difficult to recognise in medieval England.69 His views might be expanded to cover the whole of medieval Western Europe.

Franco Cardini presents an example of a ritual to protect fields against bad harvests and evil magic. It involves all kinds of Christian elements, such as use of holy water and Pater noster prayers; yet, the ritual itself is not that of liturgical blessing, but rather magical. It does not ask fertility from God, leaving the eventual outcome to His decision. The ritual is based on the assumption that prayers and holy water will produce the desired results on their charismatic power alone. It is not a question of supplication but of manipulation.70 There are numerous comparable examples in sources throughout Europe.

In Germany, the peasants used to erect big crosses near their fields. Their function was to protect the crops against bad weather and storms. Sometimes these ‘Wetterkreuze’ were given a more official status by the local clergy who consecrated them and sprinkled them with holy water. An extant manuscript from the eleventh century gives a ready-made liturgy for such an occasion. Once the cross was made, it was brought before the churchdoor on Friday. Then the mass on the Holy Cross was sung, and hereafter the priest came to the cross with blessed grain and holy water. Psalm 66 Deus misereatur and the litany against hailstorms were sung followed by the actual blessing of the cross. Holy water was sprinkled, thurible was waived, and symbols of the four evangelists were carved on the cross. The incipits of the four gospels were generally considered to be a powerful protective amulet against storms.

Finally the priest said:

‘Let this holy cross be sanctified in the name of the Father, and Son and the Holy Ghost, so that it can protect Christian people against aerial powers and spiritual enemies, who have been given the power to harm the soil…’

From this point on the text is lost and we do not know how the cross was eventually put into it’s proper position. Traces of similar ceremonies have been found from the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries.71 In the beginning of fifteenth century, Johannes von Werden wrote that the crucifix was an effective means of protection against demons that are afraid of it. Therefore, he continues, in some parishes the crucifix is taken out from the church and placed outside against the storm so that the demons can see the sign of the eternal ruler and flee in front of it.72

Similar examples can be found all over medieval Christendom. Étiennede Bourbon says that in Savoy the inhabitants of mountain regions were in the habit of erecting crosses on the mountaintops to expel demons.73 Vincent Ferrier advised people to toll the church bells and bring out the crosses for protection against storms.74 The phrasing of Vincent is not totally clear, but he seems to imply that specific crosses such as German ‘Wetterkreuze’, or it is also possible that the normal ritual crucifixes in churches were brought out to prevent storms. It seems that the use of crosses against bad weather was not only a German custom, but also known all throughout Christian Europe.

There were numerous ways of mixing religion and magic when people were seeking protection from disasters and epidemics. Some people had specific prayers written on pieces of parchment, which they carried them with them as lucky charms. Others wore different religious medallions and protective amulets. Especially popular was the Agnus Dei symbol. Others had holy water sprinkled on them as a protection against the contagion of diseases.75

The Observant Franciscan preacher Bernardino Tomitano da Feltre told his audiences that once his more famous namesake Bernardino da Siena had shown to the people of Padua and Bologna the sign of Christ, that is, the letters IHS. Many people made amulets with these letters on circumcision day and, he emphasised, no one of those who did so died of the plague. Heal so tells that the plague never struck Siena since this sign was put in the middle of the Palladio (where it still is).76

When the christianisation of Europe advanced from the twelfth century onwards, the Church adopted more uncompromising attitude towards what it called superstition, be it remnants of ancient pagan cults or superstitious applications of Christian liturgy and symbols. In his Summa Thomas Aquinas presents superstition as a vice contrary to the real religion. That was the general idea; superstitions were seen as useless tricks and rituals, which in the Late Middle Ages were more and more frequently connected with the worship of demons.77

In the thirteenth century and before, however, superstitious practices were in most cases condemned as vain and futile nonsense rather than as diabolical. They did not deserve the harsh treatment, that was reserved for heretics.78 The relative leniency of inquisitors towards different superstitious practises does not mean that these practises were considered to be harmless and were thus overlooked. There is plenty of evidence showing that this was not the case. If one looks at the important pastoral handbooks of the thirteenth century one finds that superstition is ever present in them.79

However, one should not jump to conclusions concerning the character of medieval Christianity on the basis of its love of rituals. Medieval religion consisted by no means of only magical rites baptised by giving them Christian names and functions. While there is no lack of examples of magical use of Christian rites and religious artefacts, there are equally plenty of examples of true and personal Christian devotion even among the lowest strata of medieval society. A case in point is the various revivalist movements. And furthermore, how are we to know that most or even many parishioners interpreted, say a religious procession, as some kind of magic ceremony intended to secure good harvest? Occasional cases where popular healers and other such persons used Christian lore as a magic means do not prove conclusively that this was a general way of perceiving the rites of the Church.

Medieval Christianity was neither similar to the modern, personal faith nor identical to magic disguised as religion. The truth lies somewhere between the traditional cliché of the Christian Middle Ages, and the more or less artificial construction of a dominant Indo-European folk culture. Paradoxically, the magic features of catholic Christianity caused it to be blamed as superstitious by the Enlightenment philosophers. They were accusing the Church of the very same things it had been accusing simple countrymen for centuries. For the philosophers Rogationes, relics, and miracles were all superstitious beliefs.80 Religion and magic both began to be seen as enemies of rational scientific worldview.

Heavenly Helpers

All things considered, there was logical continuity from pre-Christian times to medieval times in the practises and means of controlling nature. The only thing that changed was, that, with the christianisation of Europe, the task of controlling nature was removed from the animistic religion and pagan deities and given to God, Christ, the Virgin Mary, and to the numerous saints.

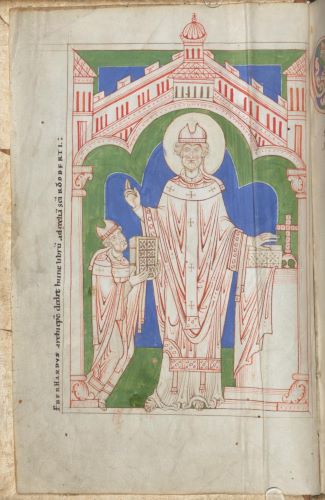

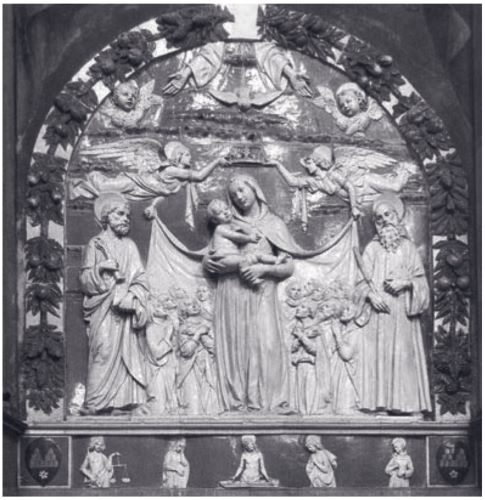

The role of the Holy Virgin as a heavenly helper in several of the dangers medieval man could encounter has been thoroughly studied. The Virgin’s most essential role was that of Mater misericordiae. She was interpreted as a gentle mother figure whose role was to protect people and try to placate the wrath of God. Christ was not generally represented as the merciful figure he has turned out to be in modern Christian thinking, but as a vengeful judge who will come to judge mankind come the day of judgement. Although there was a change in this during the later middle ages when Christ lost some of his early medieval severity.81

One of the essential roles of the saints was to control and overcome the adverse forces of nature: they defeated disease, calmed stormy seas, saved harvests from locusts, and so on. According to Carlo Cipolla the dream of a common man, harnessing nature, was reflected in the saints. Mastery of nature was a recurrent theme in medieval hagiographical writings. Several saints were reputed to be able to control the natural and animal world. One might even say that one of the essential attributes of saintliness was the power to control nature.82

Asking for the protection of saints against different natural disasters was by no means an arbitrous activity. There were good reasons for turning to a particular saint in a particular situation. In his essay on the plague in Milan, Heinrich Dormeier presented an interesting categorisation of plague saints. It can be used even more generally to describe the rules according which the different saints were chosen to protect under different threats. Dormeier distinguished three categories of plague saints:

- Traditional plague saints

- Regional plague saints, that is, saints whose intervention has been found effective in a localised area on previous occasions.

- Patron saints of a diocese, a community or of individual persons, and those saints whose feast happens to be in the time of the disaster.83

In the cases of natural disasters other than the plague, saints belonging to categories two and three were normally evoked. Some saints, for example, were regarded as specialised protectors against earthquakes. However, such attributions were often local. It is, for example, difficult to imagine that saint Agatha would have been revered as protector against earthquakes outside Sicily and Southern Italy even though these were not the only earthquake regions of the medieval Europe.84 Such local roles were not important for the image and function of that particular saint on the universal level. Here it is not important to catalogue all the saints with specific patronage to protect people against natural disasters. Suffice it to say that there were numerous such protective cults.85

It is tempting to assume that, when it comes to preventive protection against natural disasters, the role of local patron saints was the most important one. After all, they were supposed to ensure the fertility of fields and animals, and save the community from disease, storm and flood. The community confirmed the protection of the patron saint by celebrating solemnly his festival with different rites and ceremonies. In processions his relics would be carried between significant points of village territory. The banquets were organised for his/her glory and attended by all the inhabitants of community.86

A good example is the relationship between the city of Pisa and its patron, saint Peter the apostle. Federico Pisano Visconti says in a sermon that the station church chosen for the second Rogation Day was San Piero a Grado. According to the Pisan tradition it was built on the place where saint Peter first set his foot on Italian soil. Peter had personally built the first little chapel and altar. Later on the still existing church was built on the place of Peter’s chapel. It was used as a station church because saint Peter was the city’s patron saint, and because he had, as a Prince of Apostles, the power over all other saints and thus could persuade them to work on behalf of the Pisans. The sermon ends with following exhortation to prayer:

‘When Emperor Nero held the city of Pisa and had the whole body [of saint Peter] decapitated, his head remained here in the church of saint Russorio ad gradus Arnensis, which is a great sign of the fact that blessed Peter loves us, and we should love and honour him equally. We all should turn to him without fear, so that he would pray to God on behalf of us, so that God will guard our city, our souls, and bodies, and liberate us from pestilence, hunger, and sword or war, and that He would direct the ships of our merchants to harbours safely, and that He would concede us the fruits of the earth in time.’87

Thus saint Peter’s specific love of the Pisans was manifested in his willingness to stay in the city. Therefore the Pisans were able to trust in his continuous protection. There is no reason to wonder why the well-being of Pisan merchants and their ships is especially mentioned in this prayer; the well-being of the whole city was very much dependent on the fortunes of its merchants.

It is tempting to assume that other saints were only summoned to intervene when an actual catastrophe was at hand. Then the specific problem was known, and which specific saints had the qualities needed to solve it, either through their expertise or because of the fact that their feast was conveniently at hand. However, if we look into the preventive measures against possible yet unforeseen dangers, the role of patron saints was more important than that of other saints. It was he who had the duty to look after the interests of his clients.

Medieval Rationalism

An interesting question is to what extent people believed that these measures really had any effect on their safety? Living in a modern western society, we take it for granted that magical tricks are unable to produce any real effects. Magic is strongly opposed to our rational worldview. It seems absurd to many of us to assume that ceremonies such as rogationes could have been honestly believed to secure good harvests.

Indeed, we do not know what the proportion of the population was that actually believed in the effectiveness of processions, prayers, amulets or the protection of the saints. We have some documented information about the heretics who refused to believe in the teachings of the church. In addition to the heretics, it is also reasonable to assume that there were others who simply did not believe at all. Equally we have a good deal of information about people who took the protective religion most seriously, for example the thousands of written testimonies on the intervention of saints in surviving inquisitiones in partibus hearings during the canonization processes.88 However, it is impossible to know what was the ratio of believers and agnostics at any given time. Nevertheless, one must not underestimate the role of protective rites and cults from the point of view of modern ideas of what is rational and what is not.

The superiority of a rational worldview is embedded in the western tradition of thinking. We tend to believe that the western rational thought system provides us with an explicit and coherent view of the world, where everything falls into place and operates according to a rational logic of cause and effect. At the same time, the magical view of the world is considered to be incoherent. It is merely a collection of practices, beliefs, gests and ritual techniques without any real base in observation and logic.89

Relying on magic or at best on religion seems to be a sure sign of the deficient intellectual and logical capacities of medieval man. Such a view, however, is very ahistorical, and unfair. In fact, given the context, medieval people behaved very rationally. A person may act rationally, believe rationally, or both. If a person acts rationally on the basis of his beliefs, it can be called rationality in weak sense. If he is acting rationally on the basis of rationally held beliefs we are dealing with a strong form of rationality.90 In this context acting rationally according to one’s magical or religious beliefs is rationality in a weak sense of the word.

In order to decide whether or not medieval man was lacking in intelligence and logic, we should ask, whether he actually had a chance of acting rationally in the strong sense of the word. In fact, there is nothing to indicate that medieval man was not willing to do anything within his knowledge and ability that was rational in the strong sense of the word. On the contrary, numerous sources describe completely rational activities, undertaken on the basis of contemporary scientific understanding and observation to prevent disasters or alleviate their effects.

The only exception to this rule seems to be the processions at the times of plague epidemics. It was well known that the disease spread through contagion, many municipal authorities therefore had explicitly forbidden any public meetings during the epidemics. Despite this, people were willing take the risk and to organise religious processions, for they believed more in the power of divine intervention than they feared contagion.91 This is of course irrational and dangerous behaviour for anyone who knows how contagious diseases spread. Yet, for people who believe that God has ultimate control over nature, it is absolutely rational to throw oneself at His mercy.

The problem is that medieval man simply lacked the scientific knowledge available today, which would have enabled him to protect himself with measures we label rational, that is, rational in the strong sense of the word. We should not forget that the traditional religious worldview was very much self-supporting. Everything could be explained in religious terms. C. Jarvie and Joseph Agassi have noted this in the context of magic. They write, ‘The strength of the magical world-view is that it is a complete world-view, one that explains anything and everything in terms of magic, failed magic, or magical conspiracies. It combines very smoothly with even a sophisticated technology, because it explains its success.’92 This can be applied to the medieval religious worldview as well. If natural disasters cease or do not occur at all, God has obviously heard the prayers of his people. In the case of an opposite outcome, the explanation is that people have sinned, that their prayers were not earnest, or that God in his wisdom simply saw it fit to punish the community, perhaps as a trial before greater rewards.

The religious world-view was not only all-explaining, it was also presented as the only possible way of explaining the world. People were not encouraged to seek alternative solutions. Robin Horton writes about traditional culture in a modern African context. He concludes that ‘in traditional cultures there is no developed awareness of alternatives to the established body of theoretical tenets; whereas in scientifically oriented cultures, such an awareness is highly developed.’93 Those who are involved in scientific research know that Horton’s view of science is somewhat idealised; nevertheless, compared to traditional cultures it is valid.

In practise this lack of a developed awareness of alternatives meant that people were brought up within a system that was well thought-out and did not encourage questioning or experimental methods. In short, they were living in a coherent world explained by concepts and mechanisms that were taken for granted.

This becomes very clear if we consider how, in the end, the scientific monopoly of Christian Church was broken. Modern natural science was started by medieval university men, not because they wanted to question the truths presented by the Church, but because they wanted to confirm them. Alas, these most pious enquiries brought results that were not always expected. For centuries, for example, Christian scientists were looking for the traces of Noah’s flood. What they found was hard proof that the world was not created six thousand years ago, as the Church thought, but that it in fact was (as they thought) several millions of years older. It is fascinating to note that it took centuries for natural scientists to accept that the Church had got it wrong. As long as possible, they were willing to find means of explaining the evidence in such manner that it would not go against accepted doctrines.94 So one may conclude that within the historical context medieval man believed and behaved in a very rational manner.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 2 (32-47) from Strategies of Sanity and Survival, by Jussi Hanska (Finnish Literature Society, 10.31.2002), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.