Ramesses III was assassinated in the Harem conspiracy led by his secondary wife Tiye and her eldest son Pentawere.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses III was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty in Ancient Egypt. Some scholars date his reign from 26 March 1186 to 15 April 1155 BC, and he is considered to be the last great king of the New Kingdom.

His long reign saw the decline of Egyptian political and economic power, linked to a series of invasions and internal economic problems that also plagued pharaohs before him. This coincided with a decline in the cultural sphere of Ancient Egypt.[1]

However, his successful defense was able to slow down the decline, although it still meant that his successors would have a weaker military. He has also been described as a “warrior Pharaoh” due to his strong military strategies. He led the way by defeating the invaders known as “the Sea Peoples”, who had caused destruction in other civilizations and empires. He was able to save Egypt from collapsing at the time when many other empires fell during the Late Bronze Age; however, the damage of the invasions took a toll on Egypt.[2]

Rameses III constructed one of the largest mortuary temples of western Thebes, now called Medinet Habu.[3] He was assassinated in the Harem conspiracy led by his secondary wife Tiye and her eldest son Pentawere. This would ultimately cause a succession crisis which would further accelerate the decline of Ancient Egypt. He was succeeded by his son and designated successor Ramesses IV, although many of his other sons would rule later.

Name, Early Years, and Accession

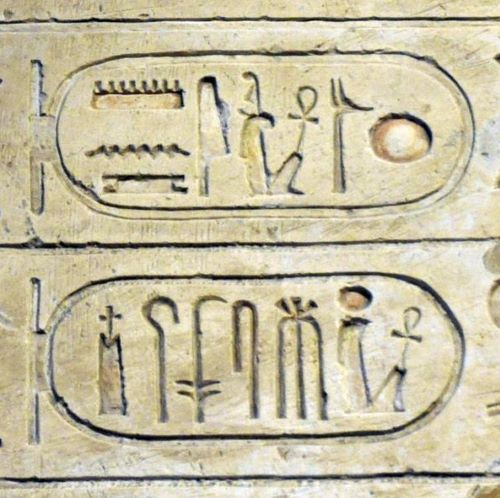

Ramesses (also written Ramses and Rameses) two main names transliterate as wsr-mꜢʿt-rʿ–mry-ỉmn rʿ-ms-s–ḥḳꜢ-ỉwnw. They are normally realised as Usermaatre-Meryamun Rameses-Heqaiunu, meaning “The Ma’at of Ra is strong, Beloved of Amun, Born of Ra, Ruler of Heliopolis”.

Ramesses III was the son of Setnakhte and Tiy-Merenese who wrote her name in a cartouche.

Ramesses III is believed to have reigned from March 1186 to April 1155 BC. This is based on his known accession date of I Shemu day 26 and his death on Year 32 III Shemu day 15, for a reign of 31 years, 1 month and 19 days.[4] Alternative dates for his reign are 1187–1156 BC.

In a description of his coronation from Medinet Habu, four doves were said to be “dispatched to the four corners of the horizon to confirm that the living Horus, Ramses III, is (still) in possession of his throne, that the order of Maat prevails in the cosmos and society”.[5][6]

Tenure of Constant War

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called Sea Peoples and the Libyans) and experienced the beginnings of increasing economic difficulties and internal strife which would eventually lead to the collapse of the Twentieth Dynasty.

In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, including Peleset, Denyen, Shardana, Meshwesh of the sea, and Tjekker, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. First, he defeated them on land in the Battle of Djahy on the Egyptian Empire’s easternmost frontier in Djahy or modern-day southern Lebanon. The second one was the Battle of the Delta, in which Ramesses enticed the Sea Peoples and their ships into the mouth of the Nile, where he had assembled a fleet in ambush. Although the Egyptians had a reputation as poor seamen, they fought tenaciously. Rameses lined the shores with ranks of archers who kept up a continuous volley of arrows into the enemy ships when they attempted to land on the banks of the Nile. Then, the Egyptian navy attacked using grappling hooks to haul in the enemy ships. In the brutal hand-to-hand fighting which ensued, the Sea Peoples were utterly defeated. The Harris Papyrus states:

As for those who reached my frontier, their seed is not, their heart and their soul are finished forever and ever. As for those who came forward together on the seas, the full flame was in front of them at the Nile mouths, while a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore, prostrated on the beach, slain, and made into heaps from head to tail.[7]

Ramesses III incorporated the Sea Peoples as subject peoples and settled them in southern Canaan. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. During the reign of Ramses III, Egyptian presence in the Levant is still attested as far as Byblos[8] and he may have campaigned further north into Syria.[9][10] Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt’s Western Delta in his Year 5 and Year 11 respectively.[11] By the early 12th century, Egypt claimed overlordship of Cyrenaican tribes. At one point a ruler chosen by Egypt was set up (briefly) over the combined tribes of Meshwesh, Libu, and Soped.[12]

Economic Turmoil

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt’s treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labour strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III’s reign, when the food rations for the favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Set Maat her imenty Waset (now known as Deir el-Medina), could not be provisioned.[13] Something in the air (possibly the Hekla 3 eruption) prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC. The result in Egypt was a substantial increase in grain prices under the later reigns of Ramesses VI-VII, whereas the prices for fowl and slaves remained constant.[14] Thus the cooldown affected Ramesses III’s final years and impaired his ability to provide a constant supply of grain rations to the workmen of the Deir el-Medina community.

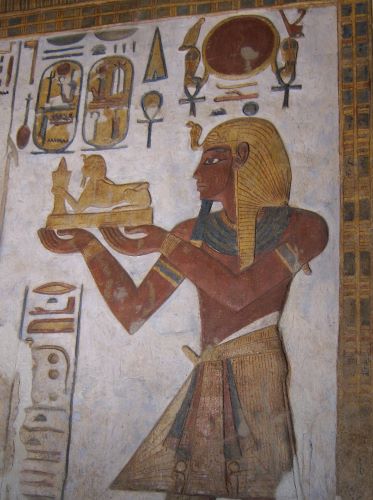

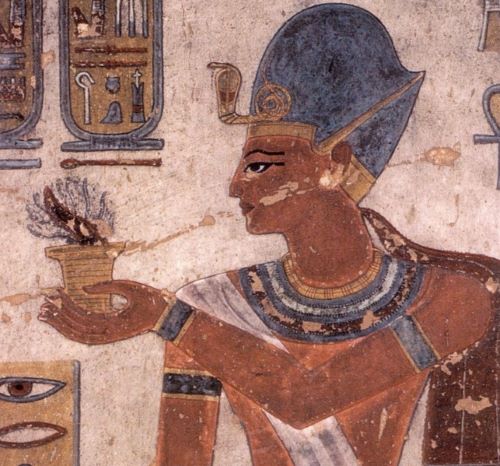

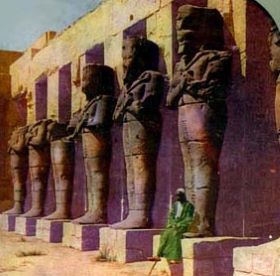

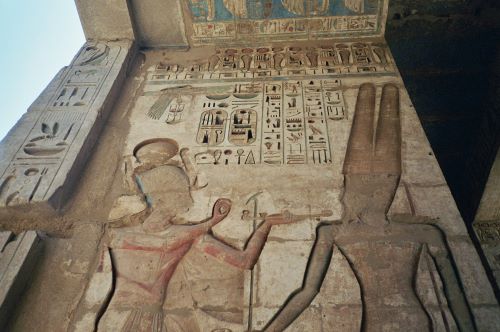

These difficult realities are completely ignored in Ramesses’ official monuments, many of which seek to emulate those of his famous predecessor, Ramesses II, and which present an image of continuity and stability. He built important additions to the temples at Luxor and Karnak, and his funerary temple and administrative complex at Medinet-Habu is amongst the largest and best-preserved in Egypt; however, the uncertainty of Ramesses’ times is apparent from the massive fortifications which were built to enclose the latter. No temple in the heart of Egypt prior to Ramesses’ reign had ever needed to be protected in such a manner.

Conspiracy and Death

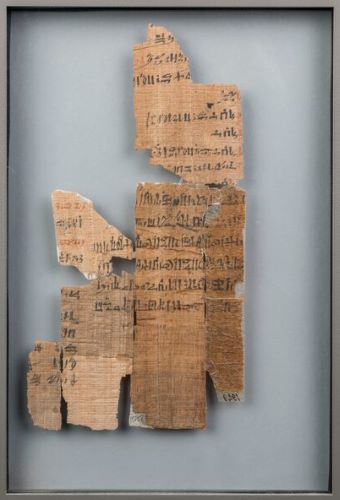

Thanks to the discovery of papyrus trial transcripts (dated to Ramesses III), it is now known that there was a plot against his life as a result of a royal harem conspiracy during a celebration at Medinet Habu On day 15 of month 2 of Shemu 1155 BCE. The conspiracy was instigated by Tiye, one of his three known wives (the others being Tyti and Iset Ta-Hemdjert), over whose son would inherit the throne. Tyti’s son, Ramesses Amenherkhepshef (the future Ramesses IV), was the eldest and the successor chosen by Ramesses III in preference to Tiye’s son Pentaweret.

The trial documents[15] show that many individuals were implicated in the plot.[16] Chief among them were Queen Tiye and her son Pentaweret, Ramesses’ chief of the chamber, Pebekkamen, seven royal butlers (a respectable state office), two Treasury overseers, two Army standard bearers, two royal scribes and a herald. There is little doubt that all of the main conspirators were executed: some of the condemned were given the option of committing suicide (possibly by poison) rather than being put to death.[17] According to the surviving trial transcripts, a total of three separate trials were started, while 38 people were sentenced to death.[18] The tombs of Tiye and her son Pentaweret were robbed and their names erased to prevent them from enjoying an afterlife. The Egyptians did such a thorough job of this that the only references to them are the trial documents and what remains of their tombs.

Some of the accused harem women tried to seduce the members of the judiciary who tried them but were caught in the act. Judges who were involved were severely punished.[19]

Ramesses IV, the king’s designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret, who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed,[21] but the same year that the trial documents[15] record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III’s body showed no obvious wounds,[19] an examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem, professors of radiology at Cairo University, revealed that beneath the bandages was a deep knife wound across the throat, deep enough to reach the vertebrae. According to the documentary narrator, “It was a wound no one could have survived.”[22] The CT scan revealed that his throat was cut to the bone, severing the trachea, esophagus, and blood vessels, which would have been rapidly fatal.[23][24] The December 2012 issue of the British Medical Journal quoted the conclusion of the study of the team of researchers, led by Zahi Hawass, the former head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity, and his Egyptian team, as well as Albert Zink from the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman of Eurac Research in Bolzano, Italy, which stated that conspirators murdered Ramesses III by cutting his throat.[23][25][26] Zink observed in an interview that:

The cut [to Ramesses III’s throat] is … very deep and quite large, it really goes down almost down to the bone (spine) – it must have been a lethal injury.[27]

A subsequent study of the CT scan of the mummy of Ramesses III’s body by Sahar Saleem revealed that the left big toe was likely chopped by a heavy sharp object like an ax. There were no signs of bone healing so this injury must have happened shortly before death. The embalmers placed a prosthesis-like object made of linen in place of the amputated toe. The embalmers placed six amulets around both feet and ankles for magical healing of the wound for the life after. This additional injury of the foot supports the assassination of the Pharaoh, likely by the hands of multiple assailants using different weapons.[28]

Before this discovery it had been speculated that Ramesses III had been killed by means that would not have left a mark on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic,[29] who might well have used poison. Some had put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a viper was the cause of the king’s death. His mummy includes an amulet to protect Ramesses III in the afterlife from snakes. The servant in charge of his food and drink were also among the listed conspirators, but there were also other conspirators who were called the snake and the lord of snakes.

In one respect the conspirators certainly failed. The crown passed to the king’s designated successor: Ramesses IV. Ramesses III may have been doubtful as to the latter’s chances of succeeding him, given that, in the Great Harris Papyrus, he implored Amun to ensure his son’s rights.[30]

DNA and Possible Relationship with His Son Pentawaret

The Zink unit determined that the mummy of an unknown man buried with Ramesses was, because of the proven genetic relationship and a mummification process that suggested punishment, a good candidate for the pharaoh’s son, Pentaweret, who was the only son to revolt against his father. It was impossible to determine his cause of death. Both mummies were predicted by Whit Athey’s STR-predictor to share the Y chromosomal haplogroup E1b1a-V38 and 50% of their genetic material, which pointed to a father-son relationship.[31]

In 2010 Hawass et al undertook detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies as part of the King Tutankhamun Family Project. The objectives included attempting to determine familial relationships among 11 royal mummies of the New Kingdom, as well to research for pathological features including potential inherited disorders and infectious diseases.[32] In 2012, Hawass et al undertook an anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study of the 20th dynasty mummies of Ramesses III and an unknown man which were found together.[23] In 2022, S.O.Y. Keita analysed 8 Short Tandem loci (STR) data published as part of these studies by Hawass et al, using an algorithm that only has three choices: Eurasians, sub-Saharan Africans, and East Asians. Using these three options, Keita concluded that the majority of the samples, which included the genetic remains of Rameses III and Tutankhamun had a population “affinity with ‘sub-Saharan’ Africans in one affinity analysis”. However, Keita cautioned that this does not mean that the royal mummies “lacked other affiliations” which he argued had been obscured in typological thinking. Keita further added that different “data and algorithms might give different results” which reflects the complexity of biological heritage and the associated interpretation.[33]

Legacy

The Great Harris Papyrus or Papyrus Harris I, which was commissioned by his son and chosen successor Ramesses IV, chronicles this king’s vast donations of land, gold statues and monumental construction to Egypt’s various temples at Piramesse, Heliopolis, Memphis, Athribis, Hermopolis, This, Abydos, Coptos, El Kab and various cities in Nubia. It also records that the king dispatched a trading expedition to the Land of Punt and quarried the copper mines of Timna in southern Canaan. Papyrus Harris I records some of Ramesses III’s activities:

I sent my emissaries to the land of Atika, [i.e., Timna] to the great copper mines which are there. Their ships carried them along and others went overland on their donkeys. It had not been heard of since the [time of any earlier] king. Their mines were found and [they] yielded copper which was loaded by tens of thousands into their ships, they being sent in their care to Egypt, and arriving safely. (P. Harris I, 78, 1–4)[34]

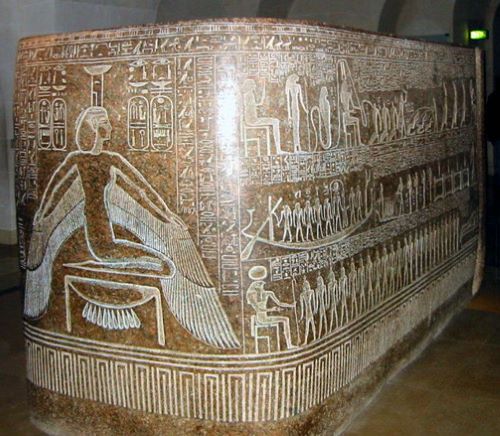

Ramesses began the reconstruction of the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak from the foundations of an earlier temple of Amenhotep III and completed the Temple of Medinet Habu around his Year 12.[35] He decorated the walls of his Medinet Habu temple with scenes of his naval and land battles against the Sea Peoples. This monument stands today as one of the best-preserved temples of the New Kingdom.[36]

The mummy of Ramesses III was discovered by antiquarians in 1886 and is regarded as the prototypical Egyptian Mummy in numerous Hollywood movies.[37] His tomb (KV11) is one of the largest in the Valley of the Kings.

In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted a series of X-ray examinations on New Kingdom Pharaohs crania and skeletal remains, which included the mummified remains of Ramesses III. The analysis in general found strong similarities between the New Kingdom rulers of the 19th Dynasty and 20th Dynasty with Mesolithic Nubian samples. The authors also noted affinities with modern Mediterranean populations of Levantine origin. Harris and Wente suggested this represented admixture as the Rammessides were of northern origin.[38]

In April 2021 his mummy was moved from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization along with those of 17 other kings and 4 queens in an event termed the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.[39]

Chronological Dispute

There is uncertainty regarding the exact dates of the reign of Ramesses III. This uncertainty affects the dating of the Late Bronze/Iron Age transition in the Levant. This transition is defined by the appearance of Mycenaean LH IIIC:1b (Philistine) pottery in the coastal plain of Palestine, generally assumed to correspond to the settlement of Sea Peoples there at the 8th year of Ramesses III.[40] Radiocarbon dates and other external evidence permit this transition to be as late as 1100 BC, compared to the conventional dating of c. 1179 BC.[41]

Some scientists have tried to establish a chronological point for this pharaoh’s reign at 1159 BC, based on a 1999 dating of the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland. Since contemporary records show that the king experienced difficulties provisioning his workmen at Deir el-Medina with supplies in his 29th Year, this dating of Hekla 3 might connect his 28th or 29th regnal year to c. 1159 BC.[42] A minor discrepancy of one year is possible since Egypt’s granaries could have had reserves to cope with at least a single bad year of crop harvests following the onset of the disaster. This implies that the king’s reign would have ended just three to four years later, around 1156 or 1155 BC. A rival date of “2900 BP” (950 BC) has since been proposed by scientists based on a re-examination of the volcanic layer.[43] Given that no Egyptologist dates Ramesses III’s reign to as late as 1000 BC, this would mean that the Hekla 3 eruption presumably occurred well after Ramesses III’s reign. A 2002 study, using high-precision radiocarbon dating of a peat deposit containing ash layers, put this eruption in the range 1087–1006 BC.[44]

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 11.06.2002, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.