Christian nationalism, not Islam, openly seeks to embed theological morality into public law while denying that it constitutes religious imposition.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Religious Freedom and the Politics of Suspicion

American political culture presents itself as uniquely committed to religious freedom, yet that commitment has never been evenly distributed. From the earliest debates over Catholic loyalty in the nineteenth century to Cold War anxieties about atheism, religious difference has repeatedly been treated as a proxy for political threat. In each case, the language of law has played a central role. Minority religious practices have been recast not as protected expressions of belief, but as covert challenges to civic order. Suspicion has followed difference, even when no evidence of legal conflict existed.

In the early twenty-first century, fears surrounding Sharia law have emerged as the most recent iteration of this pattern, shaped by post-9/11 politics, media amplification, and organized advocacy networks. American Muslims are routinely portrayed as adherents of a foreign legal system incompatible with constitutional governance, despite the absence of any institutional mechanism through which Islamic law could function as public authority in the United States. Sharia is described not as a religious or ethical framework, but as a parallel legal code waiting to be imposed. This portrayal persists even as Muslim religious practice in the United States mirrors the structure of other faith traditions: voluntary observance, personal moral discipline, communal norms, and internal dispute resolution confined to private life. The dissonance between lived reality and public rhetoric suggests that the panic is not grounded in law or constitutional structure, but in cultural fear and political narrative.

What distinguishes contemporary Sharia fear from earlier episodes is not its logic, but its selectivity. Religious influence on law is not rejected in principle within American politics. Christian moral frameworks openly shape legislation on issues such as abortion, sexuality, education, and family life, often framed as cultural tradition rather than religious doctrine. These efforts rarely provoke accusations of theocracy or legal takeover. By contrast, Muslim religious practice is treated as inherently suspect, even when it remains strictly personal and constitutionally bounded. The asymmetry reveals that the issue is not religious law as such, but which religious communities are permitted to influence public life without scrutiny.

Modern Sharia panic is best understood as a politics of suspicion rooted in contested belonging rather than legal reality. The language of religious freedom is invoked selectively, expanded to protect dominant traditions while narrowed to police minority ones. Constitutional principles are not abandoned, but unevenly applied. As in earlier historical cases, fear does not arise from actual legal imposition, but from the endurance and visibility of difference within a national identity imagined as culturally homogeneous. By examining how Sharia is imagined, debated, and legislated against in the United States, this demonstrates that contemporary anxieties about Islamic law reveal less about constitutional threat than about unresolved boundaries of American identity and the selective limits of who is allowed to count as fully American.

What Sharia Is and Is Not in the American Context

In the American context, Sharia functions not as a system of public law but as a personal and communal ethical framework embedded within voluntary religious life. For most Muslims in the United States, Sharia refers to a set of religious principles guiding prayer, fasting, charitable giving, dietary practice, family responsibility, and personal morality. These practices shape daily conduct and communal belonging rather than political authority. They are comparable in structure and scope to how Jewish Americans observe Halakha or how Christians follow denominational teachings on marriage, sexuality, conscience, and moral obligation. As lived religion, Sharia operates entirely within the same constitutional boundaries that govern all faith traditions in the United States, drawing meaning from personal commitment rather than coercive power.

Sharia has no institutional mechanism through which it could function as binding public law in the American legal system. The Constitution vests legislative authority exclusively in elected bodies and prohibits the establishment of religion. Courts apply secular law derived from statutes and precedent, not religious doctrine. While religious arbitration may occur in limited civil contexts, such as contract or family mediation, participation is voluntary and outcomes are enforceable only insofar as they conform to state and federal law. Sharia cannot override constitutional protections, statutory requirements, or judicial review.

American Muslim engagement with Sharia closely resembles patterns long accepted for other religious communities, both legally and socially. Jewish beth din arbitration, Catholic annulment proceedings, and Protestant pastoral counseling have operated for decades without provoking claims of legal subversion or divided loyalty. These practices are understood as expressions of religious freedom exercised within a secular legal framework, not as attempts to replace civil authority. When Muslims seek religious guidance in marriage, inheritance planning, dietary compliance, or ethical finance, they do so through the same voluntary mechanisms. The difference lies not in the structure of practice, but in how that practice is interpreted by outsiders who treat Islamic religious observance as uniquely suspect.

Public fears surrounding Sharia often depend on collapsing diverse legal traditions, historical practices, and extremist misrepresentations into a single imagined system of domination. Sharia is treated as a fixed and centralized code rather than a plural, interpretive tradition with no pope, no legislature, and no unified authority. This distortion ignores both Islamic legal history and contemporary American reality. It replaces empirical observation with abstraction, assuming that personal religious observance signals latent political ambition. Such reasoning mirrors earlier moral panics in which minority religious law was interpreted as inherently expansionist despite the absence of institutional capacity or intent.

Understanding what Sharia is and is not in the United States is essential to evaluating claims of legal danger. Sharia is not a parallel legal system, not a competitor to constitutional authority, and not a covert mechanism for governance. It is a religious vocabulary through which American Muslims articulate moral obligation, ethical discipline, and communal identity. Treating it as an existential threat reflects not a legal assessment, but a cultural judgment about whose religious practices are perceived as compatible with American civic life and whose are not.

The Rise of Sharia Panic in American Political Discourse

The emergence of Sharia panic in American political discourse did not arise organically from Muslim communities or from any demonstrable changes in legal practice. It developed instead through a convergence of post-9/11 fear, media amplification, and organized political entrepreneurship. In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, Islam was increasingly framed not simply as a religion practiced by millions of Americans, but as a civilizational adversary defined by suspicion and threat. Within this climate, Sharia was abstracted from lived religious practice and recast as a political ideology. This reframing allowed fear to attach not to specific actions or institutions, but to identity itself, transforming ordinary religious observance into evidence of latent disloyalty.

Political actors quickly learned that Sharia fear could be mobilized without reference to evidence. Beginning in the late 2000s, advocacy groups and media personalities promoted the idea that Islamic law posed an imminent threat to American courts, schools, and public institutions. These claims circulated despite the absence of any documented attempt to replace secular law with religious doctrine. Sharia became a symbolic shorthand for foreignness, danger, and cultural infiltration, its meaning shaped less by jurisprudence than by repetition.

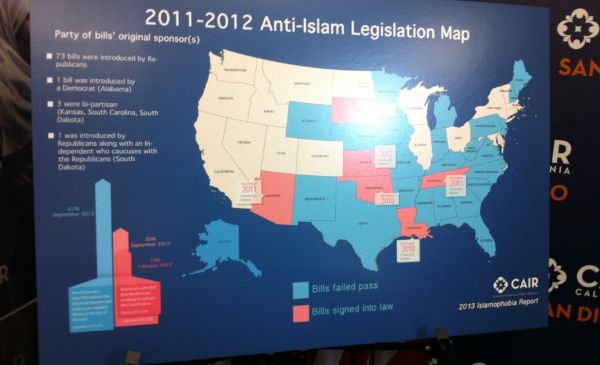

This rhetoric soon translated into legislative action that was performative rather than corrective. Between 2010 and 2018, dozens of state legislatures introduced or passed so-called anti-Sharia bills, often framed as defenses of constitutional law or preemptive safeguards against judicial overreach. In practice, these measures addressed no existing legal problem. Courts had already rejected religious law as binding authority, and constitutional safeguards rendered such legislation redundant. The purpose of these bills was not legal protection but political signaling. They publicly marked Muslims as objects of suspicion while allowing legislators to demonstrate vigilance against an imagined threat without confronting any real institutional risk.

Media narratives reinforced this legislative turn by presenting isolated anecdotes as systemic danger. Rare cases involving voluntary religious arbitration, workplace accommodation, or cultural practice were amplified and reframed as evidence of creeping theocracy. Nuance disappeared as Sharia was portrayed as monolithic, immutable, and expansionist. Complex legal traditions were flattened into caricature, and distinctions between personal ethics, communal mediation, and state law were deliberately blurred. Fear thrived on simplification rather than analysis, rewarding narratives that collapsed difference into menace and speculation into certainty.

The persistence of Sharia panic also reflects the role of networked advocacy organizations that professionalized anti-Muslim messaging. These groups produced reports, talking points, and model legislation that circulated widely among policymakers and commentators. Their influence lay not in factual accuracy, but in narrative discipline. By repeating claims often enough and across enough platforms, they normalized the assumption that Islam posed a legal threat, even as courts, scholars, and legal professionals consistently refuted it.

What makes Sharia panic particularly revealing is its resilience in the face of contradiction and empirical failure. Even as no evidence emerged to support claims of legal infiltration or judicial capitulation, the narrative endured and intensified. This persistence indicates that the panic functions less as a response to law than as a mechanism of boundary-drawing. It distinguishes insiders from outsiders, trusted citizens from suspect ones, and legitimate faith from allegedly dangerous belief. Sharia fear operates as a political language through which belonging is contested. It is not a debate about jurisprudence, but about who is imagined as fully American and who remains permanently conditional.

Law without Power: Why Sharia Cannot Be Imposed

Claims that Sharia could be imposed within the American legal system collapse under even minimal institutional scrutiny. The United States Constitution establishes a legal order in which legislative authority is vested exclusively in elected bodies, constrained by judicial review, and limited by explicit prohibitions on religious establishment. No religious doctrine, Islamic or otherwise, possesses standing as public law. Courts do not recognize religious texts as sources of binding authority, and any statute grounded explicitly in religious doctrine would fail constitutional review. The structural architecture of American law leaves no pathway for a parallel religious legal system to operate coercively.

Even in areas where religious practice intersects with civil law, participation is strictly voluntary and bounded. Religious arbitration, whether conducted by Jewish beth din, Christian mediation boards, or Muslim arbitration panels, functions only as private dispute resolution. Such agreements are enforceable solely to the extent that they comply with secular law and constitutional protections. Courts routinely invalidate religious arbitration outcomes that violate public policy, individual rights, or statutory requirements. Sharia, like all religious norms, operates here not as law but as preference, subject at every point to secular oversight.

Federalism further constrains any hypothetical religious legal takeover. Authority is divided among federal, state, and local governments, each bound by constitutional limits and judicial precedent. No centralized mechanism exists through which a religious community could capture the legal system wholesale. Moreover, American Muslims lack any unified institutional hierarchy capable of coordinating such an effort even in theory. Sharia itself is decentralized, interpretive, and plural, with no pope, legislature, or enforcement apparatus. The idea of its imposition presumes a coherence and power it does not possess.

The persistence of Sharia panic despite these structural realities reveals that the fear is not grounded in law, but in imagination. Sharia is invoked as a symbol of power precisely because it lacks it. The claim that Islamic law could overtake American governance depends on ignoring constitutional safeguards, judicial practice, and the voluntary nature of religious observance. What is presented as a legal danger is, in fact, a cultural anxiety. Sharia cannot be imposed because it has no power to impose. The fear endures not because of institutional vulnerability, but because suspicion has been detached from legal reality.

Christian Nationalism and the Normalization of Religious Law

While Sharia is framed in American political discourse as an alien and existential legal threat, Christian nationalism operates through a contrasting logic of normalization and familiarity. Rather than presenting religious influence as law, it is recast as heritage, morality, tradition, or “common values.” Biblical principles are routinely invoked to justify legislation on abortion, sexuality, marriage, education, gender roles, and public expression, yet these efforts are rarely described as the imposition of religious law. The distinction is rhetorical rather than structural. What differs is not the presence of theology in governance, but whose theology is permitted to appear culturally neutral and politically legitimate.

Christian nationalist movements do not seek separation between religious conviction and public authority. They explicitly argue that American law should reflect a Christian moral order, often claiming that the nation was founded on biblical principles and must be restored to that foundation. This project is not covert. It is articulated openly in campaign platforms, court briefs, legislative debates, judicial confirmation hearings, and policy advocacy. Yet it is frequently shielded from scrutiny by being framed as a defense of values rather than an assertion of religious authority. Law is infused with theology while insisting it remains secular, moral rather than doctrinal.

This normalization relies on historical revisionism as much as on political strategy. Christian nationalism reimagines American history as uniformly Protestant and morally unified, minimizing or distorting the constitutional commitment to religious pluralism and disestablishment. Founding-era debates over religious liberty are reframed as protections for Christianity rather than constraints upon it. By collapsing national identity into religious heritage, Christian nationalism renders its legal ambitions invisible as religion and visible only as restoration, tradition, or cultural continuity.

The contrast with Muslim religious practice is instructive. American Muslims who seek to live according to religious ethics in private and communal life are accused of harboring ambitions to impose Sharia, despite lacking institutional power, legislative access, or constitutional pathways. Christian nationalist actors, by contrast, pursue direct legal change through legislatures, courts, and administrative policy while denying that their efforts constitute religious governance. The asymmetry reveals that fear is not attached to law itself, but to religious identity. Islam is coded as foreign and suspect, Christianity as native and trustworthy.

This differential treatment is reinforced by the selective application of religious freedom and rights discourse. Christian nationalist claims are frequently framed as exercises of free exercise, conscience protection, parental authority, or religious liberty. When successful, these claims result in exemptions, privileges, and policies that align public law with specific theological commitments, often at the expense of others’ rights. Muslim religious claims rarely receive comparable deference. Instead, they are treated as potential violations of secular order or threats to social cohesion. Religious freedom functions not as a neutral constitutional principle, but as a mechanism of unequal recognition and power.

The normalization of Christian religious law alongside the demonization of Sharia exposes the true function of contemporary legal fear. The issue is not whether religious values influence law, since they demonstrably do. It is which religious communities are authorized to do so without suspicion, stigma, or accusation of disloyalty. Christian nationalism succeeds not by denying its theological basis, but by embedding it so deeply within dominant cultural identity that it ceases to appear as religion at all. In this environment, Islam is not feared because it threatens law. It is feared because it disrupts an unspoken hierarchy of belonging that determines whose moral authority counts as fully American.

The Asymmetry of Fear and the Racialization of Religion

The uneven distribution of religious suspicion in the United States cannot be explained solely through theology, constitutional doctrine, or legal structure. It is shaped instead by processes of racialization that determine which religions are perceived as compatible with national identity and which are treated as inherently suspect. Islam, in American political discourse, is rarely framed as a set of beliefs or practices alone. It is marked as foreign, collective, and immutable, attributes historically assigned to racialized groups rather than to voluntary faith communities. This framing transforms religious difference into a problem of belonging rather than belief, positioning Islam outside the imagined boundaries of Americanness regardless of doctrinal content.

Muslim identity in the United States has been persistently racialized across lines of ethnicity, nationality, and citizenship in ways that override individual biography or civic participation. Muslims are imagined as outsiders even when they are native-born, English-speaking, and generationally American, with family histories rooted in the country for decades. Religious practice becomes evidence of foreign allegiance, and visible markers of faith are read as political signals rather than expressions of conscience or culture. This racialization collapses distinctions between religion, race, and national origin, producing a form of suspicion that cannot be resolved through assimilation, military service, voting, or public conformity. Islam is treated not as a faith one practices or even a belief one holds, but as an identity one inhabits and cannot escape, rendering full civic trust perpetually conditional.

This dynamic helps explain why Sharia panic persists despite the absence of legal threat. Fear is not triggered by institutional power, legislative ambition, or constitutional vulnerability, but by the visibility of a racialized religious minority asserting presence within the civic sphere. Practices that are interpreted as harmless, private, or even virtuous when performed by Christians or Jews are recoded as dangerous when associated with Muslims. The same act of religious observance produces radically different reactions depending on who performs it and how they are positioned within racial hierarchies of trust and belonging.

The racialization of Islam also intersects with immigration politics and national security narratives. Muslims are frequently associated with border threat, terrorism, and demographic anxiety, regardless of empirical evidence or individual conduct. These associations reinforce the idea that Islam is incompatible with American civic life and that Muslim presence represents infiltration rather than participation. In this context, Sharia becomes a symbolic shorthand for fears about cultural displacement, demographic change, and the erosion of a perceived national core.

By contrast, Christianity in the United States remains largely de-racialized and normatively invisible. It is treated as cultural background rather than marked identity, allowing Christian religious influence to operate without being named as such. When Christian moral frameworks shape law, they are perceived as expressions of shared values rather than sectarian imposition. This asymmetry allows Christian nationalism to advance legal projects without triggering the same suspicion directed toward Muslim religious practice. Power appears neutral when it aligns with dominant identity.

The asymmetry of fear reveals that religious panic is not evenly distributed across traditions, but structured by race, history, and power. Islam is feared not because it poses a legal threat, but because it occupies a racialized position within American identity formation that marks it as perpetually provisional and externally sourced. Sharia panic functions as a socially acceptable language through which exclusion can be articulated without explicit reference to race, allowing discrimination to masquerade as constitutional concern. In this sense, fear of religious law becomes a proxy for deeper anxieties about who belongs, who is trusted, and who is permitted full civic legitimacy in the American polity, revealing that the true boundary being policed is not legal authority but national identity itself.

Religious Freedom Weaponized Selectively

The principle of religious freedom occupies a revered place in American constitutional thought, yet its application has long been uneven. Rather than functioning as a neutral safeguard for all forms of belief and practice, religious freedom has often been interpreted through the lens of political power and cultural familiarity. Groups perceived as part of the national core are granted expansive latitude to shape law and policy in accordance with their convictions. Minority religions, by contrast, encounter heightened scrutiny, suspicion, and restriction. The disparity reveals that religious freedom operates not simply as a right, but as a contested resource distributed unevenly across communities.

In contemporary debates, this selective application is especially visible in how claims of religious liberty are adjudicated. Christian actors invoking conscience or free exercise are frequently accommodated through exemptions, carve-outs, or policy deference, even when such accommodations impose burdens on others. These claims are framed as defenses of individual liberty rather than assertions of religious authority. Muslim claims to religious freedom, however, are more likely to be treated as potential violations of secular order or threats to constitutional norms. The same constitutional language produces radically different outcomes depending on who invokes it.

Anti-Sharia legislation offers a clear example of this asymmetry. These laws are often justified as protections of religious freedom and constitutional supremacy, yet they single out one religious tradition for restriction despite the absence of legal threat. By preemptively banning Sharia, lawmakers symbolically exclude Islam from the category of legitimate religious expression, even as other faith traditions continue to resolve internal matters through religious norms without interference. Religious freedom is invoked not to protect pluralism, but to discipline a specific minority.

This weaponization of religious liberty also reshapes public understanding of constitutional values. Rather than affirming the First Amendment’s commitment to neutrality and non-establishment, selective enforcement reinforces the idea that some religions are inherently compatible with American law while others are presumptively suspect. Freedom becomes conditional, extended fully only to those whose beliefs align with dominant cultural narratives. The constitutional promise of equal protection erodes as religious difference is recoded as legal risk.

The selective weaponization of religious freedom exposes the deeper logic animating Sharia panic and related controversies. The issue is not whether religious belief should be protected in principle, but whose belief is entitled to protection without qualification, suspicion, or political cost. When religious freedom is mobilized to shield dominant traditions while constraining minority ones, it ceases to function as a universal constitutional guarantee and instead becomes a mechanism of boundary enforcement. Under the guise of neutrality, the state effectively ranks religions according to cultural legitimacy, granting full civic trust to some while treating others as conditional participants in public life. In this way, religious freedom is transformed from a safeguard of pluralism into an instrument for policing belonging, revealing that the conflict at stake is not about law, but about who is allowed to claim America as their own.

Conclusion: Belonging, Not Law, Is the Real Question

The recurring panic over Sharia in the United States cannot be understood as a genuine concern about legal structure, constitutional vulnerability, or institutional power. As this essay has demonstrated, Islamic law lacks any mechanism for public imposition, coercive authority, or judicial standing within the American system. Courts, legislatures, and constitutional doctrine already foreclose such possibilities. The persistence of fear in the absence of legal threat reveals that the controversy is not animated by law itself, but by anxiety over difference and visibility within the national community.

Placed in historical perspective, modern Sharia panic follows a familiar pattern. From ancient Greek fears of “foreign law,” to medieval suspicions of Jewish self-governance, to European misreadings of Ottoman pluralism, religious minorities have repeatedly been accused of harboring covert legal ambitions simply by living differently under law. In each case, internal religious practice was reframed as political danger, not because it crossed jurisdictional boundaries, but because it endured. The American case is not an aberration. It is a continuation of a long tradition in which pluralism provokes fear precisely when it functions as intended.

What distinguishes the contemporary moment is the asymmetry with which religious influence is treated. Christian nationalism openly seeks to embed theological morality into public law while denying that it constitutes religious imposition. Muslim religious practice, by contrast, is scrutinized and restricted even when it remains personal, voluntary, and constitutionally compliant. This uneven application of religious freedom exposes the underlying logic of exclusion. Law is not being defended against religion. It is being used selectively to determine which religions are entitled to shape public life without suspicion and which are permanently marked as threats.

The real question, then, is not whether Sharia is compatible with American law, but whether American identity is willing to accommodate religious difference without demanding invisibility or conformity. Sharia panic operates as a language of boundary-making, distinguishing full members of the civic community from those whose belonging is treated as conditional. Religious freedom, when weaponized selectively, ceases to be a universal principle and becomes a tool for enforcing cultural hierarchy. In this light, contemporary fear of Islamic law reveals not a constitutional crisis, but an unresolved struggle over who counts as fully American and whose presence is still imagined as provisional.

Bibliography

- Ali, Wajahat, Eli Clifton, Matthew Duss, Lee Fang, Scott Keyes, and Faiz Shakir. Fear, Inc.: The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2011.

- Bail, Christopher A. Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

- Benhalim, Rabea. “Oppression in American, Islamic, and Jewish Private Law.” Colorado Law Review 94:1 (2023), 149-214.

- Cesari, Jocelyne. What Is Political Islam? Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2018.

- Feldman, Noah. Divided by God: America’s Church-State Problem and What We Should Do About It. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

- —-. The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Gorski, Philip S. American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- Green, Steven K. Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- —-. The Second Disestablishment: Church and State in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Hajnal, Zoltan L. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Hallaq, Wael B. An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Hamburger, Philip. Separation of Church and State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Khan, Saeed A. “Sharia Law, Islamophobia and the U.S. Constitution: New Tectonic Plates of Culture Wars.” University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class 12:1-4 (2012), 123-139.

- Lemons, Katherine and Joshua Takano Chambers-Letson. “Rule of Law: Sharia Panic and the US Constitution in the House of Representatives.” Cultural Studies 28:5-6 (2014), 1048-1077.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror. New York: Pantheon, 2004.

- Rasekh, Mohammad. “Sharia and Law in the Age of Constitutionalism.” Journal of Global Justice and Public Policy 2:2 (2016), 259-276.

- Selod, Saher. Forever Suspect: Racialized Surveillance of Muslim Americans in the War on Terror. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2018.

- Sullivan, Kathleen M., and Noah Feldman. Constitutional Law. New York: Foundation Press, 2019.

- Whitehead, Andrew L., and Samuel L. Perry. Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.13.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.