Edited by Matthew A. McIntosh

Historian

Brewminate Editor-in-Chief

1 – Federalism in the Constitution

1.1 – Introduction

Federalism is the system of government in which sovereignty is constitutionally divided between a central governing authority and constituent political units. It is based upon democratic rules and institutions in which the power to govern is shared between national and state governments, creating a federation. Dual federalism is a political arrangement in which power is divided between national and state governments in clearly defined terms, with state governments exercising those powers accorded to them without interference from the national government. Dual federalism is defined in contrast to cooperative federalism, in which national and state governments collaborate on policy. Dual and cooperative federalism are also known as ‘layer-cake’ and ‘marble cake’ federalism, respectively, due to the distinct layers of layer cake and the more muddled appearance of marble cake.

Federalism was the most influential political movement arising out of discontent with the Articles of Confederation, which focused on limiting the authority of the federal government. The movement was greatly strengthened by the reaction to Shays’ Rebellion of 1786-1787, which was an armed uprising of farmers in western Massachusetts. The rebellion was fueled by a poor economy that was created, in part, by the inability of the federal government to deal effectively with the debt from the American Revolution. Moreover, the federal government had proven incapable of raising an army to quell the rebellion, so Massachusetts was forced to raise its own.

The most forceful defense of the new Constitution was The Federalist Papers , a compilation of 85 anonymous essays published in New York City to convince the people of the state to vote for ratification. These articles, written by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, examined the benefits of the new Constitution and analyzed the political theory and function behind the various articles of the Constitution. Those opposed to the new Constitution became known as the Anti-Federalists. They were generally local, rather than cosmopolitan, in perspective, oriented toward plantations and farms rather than commerce or finance, and wanted strong state governments with a weaker national government. The Anti-Federalists believed that the legislative branch had too much unchecked power, that the executive branch had too much power, and that there was no check on the chief executive. They also believed that a Bill of Rights should be coupled with the Constitution to prevent a dictator from exploiting citizens. The Federalists argued that it was impossible to list all the rights and that those not listed could be easily overlooked because they were not in the official bill of rights.

The Federalist Papers: Title page of the first printing of the Federalist Papers.

After the Civil War, the federal government increased its influence on everyday life and its size relative to state governments. Reasons included the need to regulate businesses and industries that spanned state borders, the attempts to secure civil rights, and the provision of social services. The federal government acquired no substantial new powers until the acceptance by the Supreme Court of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. From 1938 until 1995, the Supreme Court did not invalidate any federal statute as exceeding Congress ‘ power under the Commerce Clause.

The Great Depression marked an abrupt end to dual federalism and a dramatic shift to a strong national government. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies reached into the lives of U.S. citizens like no other federal measure had done. As the Supreme Court rejected nearly all of Roosevelt’s economic proposals, in 1936, the president proposed appointing a new Supreme Court justice for each sitting justice aged 70 or older. The expansion of the court, along with a Democrat-controlled Congress, would tilt court rulings in favor of Roosevelt’s policies.

The national government was forced to cooperate with all levels of government to implement the New Deal policies; local government earned an equal standing with the other layers, as the federal government relied on political machines at the city level to bypass state legislatures. In the final analysis, federalism in the United States has been structured to protect minority rights while giving enough power to the states to control their own affairs. This conflict and duality remains a contested territory, especially after the Reagan devolution and his insistence on “marble-cake” federalism.

1.2 – The Power of National Government

The federal government is composed of three branches: legislative, executive and judicial. Powers are vested in Congress, in the President, and the federal courts by the United States Constitution. The powers and duties of these branches are further defined by acts of Congress, including the creation of executive departments and courts inferior to the Supreme Court.

The government was formed in 1789, making the United States one of the world’s first, if not the first, modern national constitutional republic. It is based on the principle of federalism, where power is shared between the federal government and state governments. The powers of the federal government have generally expanded greatly since the Civil War. However, there have been periods of legislative branch dominance since then. Also, states’ rights proponents have succeeded in limiting federal power through legislative action, executive prerogative, or constitutional interpretation by the courts. A theoretical pillar of the United States Constitution is the idea of checks and balances between the powers and responsibilities of the three branches of American government.

Congress: The U.S. Congress holds legislative power.

Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government. It is bicameral, comprised of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Constitution grants numerous powers to Congress, including the power to:

- levy and collect taxes,

- coin money and regulate its value,

- provide punishment for counterfeiting,

- establish post offices and roads,

- promote progress of science by issuing patents,

- create federal courts inferior to the Supreme Court,

- combat piracies and felonies,

- declare war,

- raise and support armies,

- provide and maintain a navy,

- make rules for the regulation of land and naval forces,

- exercise exclusive legislation in the District of Columbia,

- make laws necessary to properly execute powers.

Since the United States was formed, many disputes have arisen over the limits on the powers of the federal government in the form of lawsuits ultimately decided by the Supreme Court.

The executive power in the federal government is vested in the President, although power is often delegated to the Cabinet members and other officials. The President and Vice President are elected as running mates by the Electoral College for which each state, as well as the District of Columbia, is allocated a number of seats based on its representation in both houses of Congress. The President is limited to a maximum of two four-year terms. If the President has already served two years or more of a term to which some other person was elected, he may only serve one more additional four-year term.

The Judiciary explains and applies the laws. This branch hears and eventually makes decisions on various legal cases. Article III, section I of the Constitution establishes the Supreme Court of the United States and authorizes the United States Congress to establish inferior courts as their need shall arise. Section I also establishes a lifetime tenure for all federal judges and states that their compensation may not be diminished during their time in office. Article II, section II establishes that all federal judges are to be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

1.3 – The Powers of State Government

1.3.1 – Introduction

Map of the United States: Map of the United States. Each of the state has its own government.

State governments in the United States are the republics formed by citizens in the jurisdiction as provided by the Constitution. State governments are structured in accordance with state law and they share the same structural model as the federal system; they also contain three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. The Tenth Amendment states that all governmental powers not granted to the federal government by the Constitution are reserved for the states or the people.

1.3.2 – Legislative Branch

The legislative branch of the states consists of state legislatures. Every state except for Nebraska has a bicameral legislature, comprised of two chambers. In the majority of states, the state legislature is called the Legislature. The rest of the states call their legislature the General Assembly.

1.3.3 – Executive Branch

An elected Governor heads the executive branch of every state. Most states have a plural executive, where several key members of the executive branch are directly elected by the people and serve alongside the Governor. These include the offices of Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, auditors, Treasurer, Commissioner of Agriculture, and Commissioner of Education. Each state government is free to organize its executive departments and agencies in any way it likes, resulting in substantial diversity among the states with regard to every aspect of how their governments are organized.

1.3.4 – Judicial Branch

A supreme court that hears appeals from lower state courts heads the judicial branch in most states. Each state’s court has the last word on issues of state law and can only be overruled by federal courts on issues of Constitutional law. The structure of courts and the methods of selecting judges are determined by each state’s constitution or legislature. Most states have at least one trial-level court and an intermediate appeals court from which only some cases are appealed to the highest court.

1.4 – The Powers of Local Government

Powers of local governments are defined by state rather than federal law, and states have adopted a variety of systems of local government.

New York City – City Hall: NYC City Hall is home to the government of the largest city in the US, and the municipality with the largest budget.

Local government in the United States is structured in accordance with the laws of the individual states, territories and the District of Columbia. Typically each state has at least two separate tiers of local government: counties and municipalities. Some states have their counties further divided into townships. There are several different types of local government at the municipal level, generally reflecting the needs of different levels of population densities; typical examples include the city, town, borough and village.

The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution makes local government a matter of state rather than federal law, with special cases for territories and the District of Columbia. The states have adopted a wide variety of systems of local government. The US Census Bureau conducts the Census of Governments every five years to compile statistics on government organization, public employment, and government finances. The categories of local government established in this Census of Governments is a convenient basis for understanding local government: county governments, town or township governments, municipal governments and special-purpose local governments.

County governments are organized local governments authorized in state constitutions and statutes. Counties form the first-tier administrative division of the states. All the states are divided into counties for administrative purposes. A number of independent cities operate under a municipal government that serves the functions of both city and county. In areas lacking a county government, services are provided either by lower level townships or municipalities or the state.

Town or township governments are organized local governments authorized in the state constitutions and statutes of states, established to provide general government for a defined area, generally based on the geographic subdivision of a county. Depending on state law and local circumstance, a township may or may not be incorporated, and the degree of authority over local government services may vary greatly. In particular, towns in New England have considerably more power than most townships elsewhere and often function as independent cities in all but name, typically exercising the full range of powers that are divided between counties, townships and cities in other states.

Municipal governments are organized local governments authorized in state constitutions and statutes, established to provide general government for a defined area, generally corresponding to a population center rather than one of a set of areas into which a county is divided. The category includes those governments designated as cities, boroughs, towns, and villages. This concept corresponds roughly to the incorporated places that are recognized in Census Bureau reporting of population and housing statistics. Municipalities range in size from the very small to the very large, reflected in the range of types of municipal governments that exist in different areas.

In most states, county and municipal governments exist side-by-side. In some states, a city can become independent of any separately functioning county government and function both as a county and as a city. Depending on the state, such a city is known as either an independent city or a consolidated city-county. Municipal governments are usually administratively divided into several departments, depending on the size of the city.

1.5 – Interstate Relations

Article Four of the United States Constitution outlines the relationship between the states, with Congress having power to admit new states.

In the United States, states are guaranteed military and civil defense by the federal government. The federal government is also required to ensure that the government of each state remains a republic. Four states use the official name of Commonwealth, rather than State. However, this is merely a paper distinction. The United States Constitution uniformly refers to all of these sub-national jurisdictions as States.

The United States: Americans live in a federal system of 50 states that, together, make up the United Sates of America.

Under Article Four of the United States Constitution, which outlines the relationship between the states, the United States Congress has the power to admit new states to the Union. The Article imposes prohibitions on interstate discrimination that are central to our status as a single nation. The states are required to give full faith and credit to the acts of each other’s legislatures and courts, which is generally held to include the recognition of legal contracts, marriages, criminal judgments, and before 1865, slavery status. States are prohibited from discriminating against citizens of other states with respect to their basic rights, under the Privileges and Immunities Clause. Under the Extradition Clause, a state must extradite people located there who have fled charges of treason, felony, or other crimes in another state if the other state requests extradition.

The Article contends that the Constitution grants Congress expansive authority to structure interstate relations and that in wielding this interstate authority Congress is not limited by judicial interpretations of Article 4. The provisions are judicially enforceable against the states. However, the ability to enforce the provisions is dependent on the absence of congressionally authorized discrimination.

1.6 – Concurrent Powers

Concurrent powers are the powers that are shared by both the State and the federal government, exercised simultaneously.

The United States Constitution affords some powers to the national government without barring them from the states. Concurrent powers are powers that are shared by both the State and the federal government. These powers may be exercised simultaneously within the same territory and in relation to the same body of citizens. These concurrent powers including regulating elections, taxing, borrowing money and establishing courts. National and state governments both regulate commercial activity.

Congress of Confederation and the Constitution: The signing of the Constitution of the United States.

As Alexander Hamilton explained in The Federalist #32, “the State governments would clearly retain all the rights of sovereignty which they before had, and which were not, by that act, exclusively delegated to the United States. ” Hamilton goes on to explain that this alienation would exist in three cases only: where there is in express terms an exclusive delegation of authority to the federal government, as in the case of the seat of government; where authority is granted in one place to the federal government and prohibited to the states in another, as in the case of imposts; and where a power is granted to the federal government “to which a similar authority in the States would be absolutely and totally contradictory and repugnant, as in the case of prescribing naturalization rules. ”

In the Commerce Clause, the Constitution gives the national government broad power to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, among several of the States and with the Indian tribes. This clause allowed the federal government to establish a national highway system that connected the states. A state may regulate any and all commerce that is entirely within its borders.

National and state governments make and enforce laws themselves and choose their own leaders. They have their own constitutions and court systems. A state’s Supreme Court decision may be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court provided that it raises a federal question, such as an interpretation of the U.S. Constitution or of national law.

1.7 – The Supremacy Clause

1.7.1 – Constitutional Basis

Article VI, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Supremacy Clause, establishes the U.S. Constitution, Federal Statutes, and U.S. Treaties as “the supreme law of the land. ” The text decrees these to be the highest form of law in the U.S. legal system and mandates that all state judges must follow federal law when a conflict arises between federal law and either the state constitution or state law from any state. The Supremacy Clause only applies if the federal government is acting in pursuit of its constitutionally authorized powers, as noted by the phrase “in pursuance thereof” in the actual text of the Supremacy Clause itself.

1.7.2 – The Federalist Papers and Ratification

The Federalist Papers: The Federalist Papers, which advocate the ratification of the Constitution.The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays advocating the ratification of the Constitution. Two sections of the essays deal with the Supremacy Clause, in which Alexander Hamilton argues that the Supremacy Clause is simply an assurance that the government’s powers can be properly executed. James Madison similarly defends the Supremacy Clause as vital to the functioning of the nation, noting that state legislatures were invested with all powers not specifically defined in the constitution, but also having the federal government subservient to various state constitutions would be an inversion of the principles of government.

In Ware v. Hylton (1796), the Supreme Court relied on the Supremacy Clause for the first time to strike down a state statute. The state of Virginia passed a statute during the Revolutionary War allowing the state to confiscate debt payments to British creditors. The Court found this Virginia statute inconsistent with the Treaty of Paris with Britain, which protected the rights of British creditors. The Court held that the Treaty superseded the Virginia statute and it was the duty of the courts to declare the Virginia statute “null and void. “Case Law Helps Define Ratification

In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Supreme Court reviewed a tax levied by the state of Maryland on the federally incorporated Bank of the United States. The Court found that if a state had the power to tax a federally incorporated institution, then the state effectively had the power to destroy the federal institution, thereby thwarting the intent and purpose of Congress. The Court found that this would be inconsistent with the Supremacy Clause, which makes federal law superior to state law.

In Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816) and Cohens v. Virginia (1821), the Supreme Court held that the Supremacy Clause and the judicial power granted in Article III give the Supreme Court power to review state court decisions involving issues arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States.

In Ableman v. Booth (1859), the Supreme Court held that state courts cannot issue rulings contradictory to decisions of federal courts, citing the Supremacy Clause, and overturning a decision by the Supreme Court of Wisconsin.

In Pennsylvania v. Nelson (1956) the Supreme Court struck down the Pennsylvania Sedition Act, which made advocating the forceful overthrow of the federal government a crime under Pennsylvania state law. The Supreme Court held that when federal interest in an area of law is sufficiently dominant, federal law must be assumed to preclude enforcement of state laws on the same subject; and a state law is not to be declared a help when state law goes farther than Congress has seen fit to go.

In Cooper v. Aaron (1958), the Supreme Court rejected attempts by the state of Arkansas to nullify the Court’s school desegregation decision, Brown v. Board of Education. The state of Arkansas had adopted several statutes designed to nullify the desegregation ruling. The Court relied on the Supremacy Clause to hold that the federal law controlled and could not be nullified by state statutes or officials.

In Edgar v. Mite Corporation (1982), the Supreme Court ruled that a state statute is void to the extent that it actually conflicts with a valid Federal statute.

There has been some debate as to whether or not some of the basic principles of the United States Constitution could be affected by a treaty. In the 1950s, a Constitutional Amendment known as the Bricker Amendment was proposed in response, which would have mandated that all American treaties shall not conflict with the manifest powers granted to the Federal Government.

1.8 – Powers Denied to Congress

Congress has numerous prohibited powers dealing with habeas corpus, regulation of commerce, titles of nobility, ex post facto and taxes.

Section 9 of Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution provided limits on Congressional powers. These limits are as follows:

- The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit (referring to the slave trade) shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

- The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.

- No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.

- No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or Enumeration herein before directed to be taken.

- No Tax or Duty shall be laid on Articles exported from any State.

- No Preference shall be given by any Regulation of Commerce or Revenue to the Ports of one State over those of another: nor shall Vessels bound to, or from, one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay Duties in another.

- No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.

- No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

1.9 – Vertical Checks and Balances

Checks and balances is a governmental structure that gives each of the branches a degree of control over the actions of the other.

To prevent one branch of government from becoming supreme, to protect the minority from the majority, and to induce the branches to cooperate, government systems employ a separation of powers in order to balance each of the branches. This is accomplished through a system of checks and balances which allows one branch to limit another, such as the power of Congress to alter the composition and jurisdiction of the federal courts. The Constitution and its amendments outline distinct powers and tasks for national and state governments. Some of these constitutional provisions enhance the power of the national government; others boost the power of the states.

The U.S. Constitution: The Constitution originally established that, in most states, all white men with property were permitted to vote. White working men, almost all women, and other people of color were denied the franchise until later years.

The legislative branch (Congress) passes bills, has broad taxing and spending power, controls the federal budget and has power to borrow money on the credit of the United States. It has sole power to declare, as well as to raise, support, and regulate the military. Congress oversees, investigates, and makes the rules for the government and its officers. It defines by law the jurisdiction of the federal judiciary in cases not specified by the Constitution. Congress is in charge of ratifying treaties signed by the President and gives advice and consent to presidential appointments to the federal, judiciary, and executive departments. The branch has sole power of impeachment (House of Representatives) and trial of impeachments ( Senate ), meaning it can remove federal executive and judicial officers from office for high crimes and misdemeanors.

The executive branch (President) is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. He executes the instructions of Congress, may veto bills passed by Congress, and executes the spending authorized by Congress. The president declares states of emergency, publishes regulations and executive orders, makes executive agreements, and signs treaties (ratification of these treaties requires the vote of two-thirds of the Senate). He makes appointments to the federal judiciary, executive departments, and other posts with the advice and consent of the Senate, and has power to make temporary appointments during the recess of the Senate. This branch has the power to grant “reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment. ”

The judicial branch ( Supreme Court ) determines which laws Congress intended to apply to any given case, exercises judicial review, reviewing the constitutionality of laws and determines how Congress meant the law to apply to disputes. The Supreme Court arbitrates how a law acts to determine the disposition of prisoners, determines how a law acts to compel testimony and the production of evidence. The Supreme Court also determines how laws should be interpreted to assure uniform policies in a top-down fashion via the appeals process, but gives discretion in individual cases to low-level judges. The amount of discretion depends upon the standard of review, determined by the type of case in question. Federal judges serve for life.

2 – Fiscal Federalism

2.1 – The New Deal

2.1.1 – Introduction

The New Deal was a series of economic programs enacted in the U.S. between 1933 and 1936 that involved presidential executive orders passed by Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were a response to the Great Depression. They focused on the “3 Rs”: relief, recovery, and reform. Relief was offered to the unemployed and poor; recovery was intended to bring the economy to normal levels; and system reform was hoped would prevent a repeat depression.

Before the New Deal, deposits at banks were not insured against loss. When thousands of banks faced bankruptcy, many people lost all their savings. There was no national safety net, no public unemployment insurance, and no Social Security. Franklin D. Roosevelt entered office with no specific set of plans for dealing with the Great Depression. Faced with the catastrophe he established an informal brain trust: a group of advisers who tended to hold positive views of pragmatic government intervention in the economy.

2.1.2 – The First and Second New Deals

Many historians distinguish between a First New Deal (1933–34) and a Second New Deal (1935–38). The First New Deal dealt with diverse groups that needed help for economic survival, from banking and railroads to industry and farming. The Federal Emergency Relief Association (FERA), for instance, provided $500 million for relief operations by states and cities, while the Civil Works Administration (CWA) gave localities money to operate make-work projects. The second was more liberal and more controversial.

The Second New Deal was begun in the spring of 1935. The Administration proposed or endorsed several important new initiatives in response to setbacks in the Court, a new skepticism in Congress, and growing popular clamor for more dramatic action. It included a national work program, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), that made the federal government the largest single employer in the nation. The other major innovations of New Deal legislation were the creation of the U.S. Housing Authority and Farm Security Administration, both begun in 1937, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which set maximum hours and minimum wages for most categories of workers.

2.1.3 – Political Realignment

The New Deal produced a political realignment. The Democratic Party became the majority party, with its base in liberal idealists, the white South, traditional Democrats, big city political machines and the newly empowered labor unions and ethnic minorities. The Republican Party was split. Conservatives opposed the entire New Deal as an enemy of business and growth; liberals accepted some of it but promised to make it more efficient. This realignment crystallized into the New Deal Coalition that dominated most presidential elections into the 1960s, while the opposition Conservative Coalition largely controlled Congress from 1937 to 1963.

This realignment represented a significant shift in politics and domestic policy. It led to greatly increased federal regulation of the economy. It also marked the beginning of complex social programs and the growing power of labor unions. The effects of the New Deal remain a source of controversy and debate among economists and historians.

2.2 – Federal Grants and National Efforts to Influence the Stats

2.2.1 – Federal Grants

In the United States, federal grants are economic aid issued by the federal government out of the general federal revenue. A federal grant is an award of financial assistance from a federal agency to a recipient to carry out a public purpose of support or stimulation authorized by a law of the United States. A grant is not used to acquire property or services for the federal government’s direct benefit. They may also be issued by private non-profit organizations such as foundations, not-for-profit corporations or charitable trusts. For instance, PBS, the network on which Big Bird features, relies heavily upon federal grants.

Federal Grants and the 2012 Presidential Election: Republican candidate, Mitt Romney, claimed that he would cut federal grants to organizations like PBS to reduce the federal budget deficit. He famously declared, “I like PBS, I love Big Bird. Actually like you, too. But I’m not going to – I’m not going to keep on spending money on things to borrow money from China to pay for. That’s number one. “

Federal grants are defined and governed by the Federal Grant and Cooperative Agreement Act of 1977. When an awarding agency expects to be substantially involved in a project, the law requires use of a cooperative agreement instead. When the government is procuring goods or services for its own direct benefit, and not for a broader public purpose, the law requires use of a federal contract.

2.2.2 – Types of Grants

There are four main types of grants available:

- Block grants—large grants provided by the federal government to state or local governments for use in a general purpose.

- Project grants—grants given by the government to fund research projects, such as medical research. Certain qualifications must be acquired before applying for a project grant and the normal duration is three years.

- Formula grants—grants that provide funds as dictated by a law.

- Earmark grants— grants are explicitly specified in appropriations of the U.S. Congress. They are not competitively awarded and are highly controversial due to the heavy involvement of paid political lobbyists used in securing them.

- Categorical Grants – Categorical Grants are grants, issued by the United States Congress, which may be spent only for narrowly-defined purposes. Categorical grants are the main source of federal aid to state and local government, can only be used for specific purposes and for helping education, or categories of state and local spending. Categorical grants are distributed either on a formula basis or a project basis. For project grants, states compete for funding; the federal government selects specific projects based on merit. Formula grants, on the other hand, are distributed based on a standardized formula set by Congress.

2.2.3 – Criticisms

Federal and state grants frequently receive criticism because they are perceived as excessive regulations and excluding opportunities for small business. These criticisms include problems of overlap, duplication, excessive categorization, insufficient information, varying requirements, arbitrary federal decision-making, and grantsmanship.

2.3 – Federal Mandates

Federal Mandates are used to implement activities to state and local governments since the post-New Deal era.

An intergovernmental mandate refers to the responsibilities or activities that one level of government imposes on another by constitutional, legislative, executive, or judicial action. According to the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act of 1995 (UMRA), an intergovernmental mandate can take various forms. An enforceable duty refers to any type of legislation, statute, or regulation that requires or proscribes an action of state or local governments, excluding actions imposed as conditions of receiving federal aid. Certain changes in large entitlement programs refers to instances when new conditions or reductions in large entitlement programs, providing $500 million or more annually to state or local governments, are imposed by the federal government. Lastly, a reduction in federal funding for an existing mandate refers to a reduction or elimination of federal funding authorized to cover the costs of an existing mandate. Mandates can be applied either vertically or horizontally. Vertically applied mandates refer to mandates directed by a level of government at a single department or program. Horizontally applied mandates refer to mandates that affect various departments or programs.

In the United States, unfunded federal mandates are orders that induce responsibility, action, procedure, or anything else that is imposed by constitutional, administrative, executive, or judicial action for state governments, local governments, and the private sector. An unfunded mandate is a statute or regulation that requires a state or local government to perform certain actions, with no money provided for fulfilling the requirements. Public individuals or organizations also can be required to fulfill public mandates.

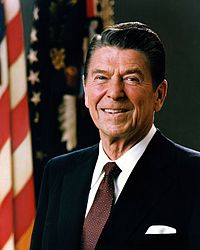

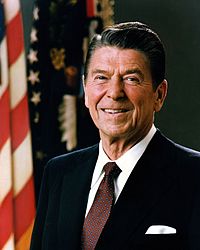

40th President of the USA, Ronald Reagan: During the Reagan Administration, Executive Order 12291 and the State and Local Cost Estimate Act of 1981 were passed. They implemented a careful examination of the true costs of federal unfunded mandates.

The first wave of major mandates occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, concerning areas including civil rights, education, and the environment. Starting with the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the U.S. federal government designed laws that required spending by state and local governments to promote national goals. During the 1970s, the national government promoted education, mental health, and environmental programs by implementing grant projects at a state and local level.

The increase of mandates in the 1980s and 1990s incited state and local protest. During the Reagan Administration, Executive Order 12291 and the State and Local Cost Estimate Act of 1981 were passed, implementing a careful examination of the true costs of federal unfunded mandates. In October 1993, state and local interest groups sponsored a National Unfunded Mandates Day, involving press conferences and appeals to congressional delegations about mandate relief. In early 1995, Congress passed unfunded mandate reform legislation. The period between the New Deal era and the mid-1980s witnessed a court that generally utilized an expansive interpretation of the interstate commerce clause and the Fourteenth Amendment to validate the growth of the federal government’s involvement in domestic policymaking. As of 1992, there were 172 federal mandates that obligated state or local governments to fund programs to some extent.

3 – The History of Federalism

Many early U.S. Supreme Court decisions, such as McCulloch v. Maryland, established the rights of power between federal and state governments.

3.1 – Supreme Court Cases

3.1.1 – McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

On April 8, 1916, Congress passed an act providing the incorporation of the Second Bank of the US. The Bank went into full operation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and in Baltimore, Maryland in 1817, carrying out business as a branch of the Bank of the US.

On February 11, 1818, the General Assembly of Maryland passed an act placing a tax on all banks not chartered by the legislature. Maryland attempted to impede operations of a branch of the Second Bank of the US by imposing a tax on all bank notes not chartered in Maryland. The Second Bank of the US was the only out-of-state bank in Maryland and the law was perceived to be targeting the US Bank. James McCulloch, head of the Baltimore Branch of the Second Bank of the US, refused to pay the tax.

Text of McCulloch v. Maryland decision: Handed down on March 6, 1819, the text of the McCulloch v. Maryland decision appears as recorded in the minutes of the Supreme Court

The lawsuit was filed by John James, an informer seeking to collect half the fine. The case was appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals where the state argued that the Constitution is silent on the subject of banks because the Constitution did not specifically state that the federal government was authorized to charter a bank. The court upheld Maryland and the case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Both sides of the litigation admitted that the Bank had no authority to establish the Baltimore branch. Chief Justice John Marshall believed that the case established the principles that the Constitution grants Congress implied powers for implementing the Constitution’s expressed powers, in order to create a functional national government and that state action may not impede valid constitutional exercises of power by the federal government.

The court determined that Congress had the power to create the Bank. Marshall supported this with four arguments. First, historical practice established Congress’ power to create the Bank. Second, he argued that it was the people who ratified the Constitution and thus the people are sovereign, not the states. Third, Marshall admitted that the Constitution does not enumerate a power to create a central bank but that this is not dispositive to Congress’ power to establish such an institution. Fourth, he invoked the Necessary and Proper Clause, permitting Congress to seek an objective within its enumerated power so long as it is rationally related to the objective and not forbidden by the Constitution. The Court rejected Maryland’s interpretation of the clause and determined that Maryland may not tax the Bank without violating the Constitution.

3.1.2 – Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

In 1808 The Legislature of New York granted Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton exclusive navigation privileges to waters within the jurisdiction of the state. They petitioned other states and territorial legislatures for similar monopolies, hoping to develop a national network of steamboat lines. Only the Orleans Territory accepted and awarded them a monopoly in the lower Mississippi. Competitors challenged Livingston and Fulton, arguing that the commerce power of the Federal government was exclusive and superseded state laws. In response to legal challenges, they attempted to undercut their rivals by selling them franchises or buying their boats.

Former New Jersey Governor Aaron Ogden tried defying the monopoly, but purchased a license from Livingston and Fulton in 1815 and entered business with Tomas Gibbons from Georgia. The partnership collapsed in 1818 when Gibbons operated another steamboat on Ogden’s route between Elizabeth, NJ and New York City, licensed by Congress under a 1793 law regulating coasting trade. They ended up in the New York Court of Errors, which granted a permanent injunction against Gibbons in 1820.

Ogden filed a complaint in the Court of Chancery of New York asking to restrain Gibbons from operating on those waters, contending that states passed laws on issues regarding interstate matters and states should have concurrent power with Congress on matters concerning interstate commerce. Gibbons’ lawyer argued that Congress had exclusive national power over interstate commerce according to Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. The Court of Chancery and the Court of Errors of New York were in favor of Ogden and issued an injunction restricting Gibbons from operating his boats. Gibbons appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the monopoly conflicted with federal law.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gibbons, arguing that the source of Congress’ power to promulgate the law was the Commerce Clause. Chief Justice Marshall’s ruling determined that a congressional power to regulate navigation is granted. The court went on to conclude that congressional power over commerce should extend to the regulation of all aspects of it.

3.1.3 – Barron v. Baltimore (1833)

John Barron co-owned a profitable wharf in the Baltimore harbor and sued the mayor of Baltimore for damages, claiming that when the city had diverted the flow of streams while engaging in street construction, it had created mounds of sand and earth near his wharf making the water too shallow for most vessels. The trail court awarded Barron damages of $4,500, but the appellate court reversed the ruling.

The Supreme Court decided that the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee that government takings of private property for public use require just compensation is a restriction upon the federal government. Chief Justice Marshall held that the first ten amendments contain no expression indicating an intention to apply them to the state governments.

The case stated that the freedoms guaranteed by the Bill of Rights did not restrict the state governments. Later Supreme Court rulings would reaffirm this ruling and, beginning in the early 20th century, the Supreme Court used the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to apply most of the Bill of Rights to the states through the process of selective incorporation.

3.2 – Federal and the Civil War: The Dred Scott Decision and Nullification

The Dred Scott Decision questioned the authority of the federal government over individual states in dealing with the issue of slavery.

Dred Scott was born a slave in Virginia and in 1820 was taken by his owner, Peter Blow, to Missouri. In 1832, Blow died and U.S. Army Surgeon Dr. John Emerson purchased Scott. Emerson took him to Fort Armstrong, Illinois, which prohibited slavery in its 1819 constitution. In 1836, Scott was relocated to Fort Snelling, Wisconsin, where slavery was prohibited under the Wisconsin Enabling Act. Scott legally married Harriet Robinson, with the knowledge and consent of Emerson in Fort Snelling.

Dred Scott: Dred Scott, the plaintiff in the Dred Scott decision, who sued for his freedom in a Missouri Court.

In 1837, Emerson was ordered to Jefferson Barracks Military Post, south of St. Louis, Missouri. Emerson left Scott and Harriet at Fort Snelling, renting them out for profit. Emerson was reassigned to Fort Jessup, Louisiana, where he married Eliza Sanford. He sent for Scott and Harriet and while en route, Scott’s daughter Eliza was born on along the Mississippi River between Iowa and Illinois. By 1840, Emerson’s wife, Scott, and Harriet returned to St. Louis while Emerson served in the Seminole War. Emerson left the Army and died in 1843. Eliza inherited his estate and continued to rent Scott out as a slave. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his family’s freedom, but Eliza refused, prompting Scott to resort to legal action.

Scott sued Emerson for his freedom in a Missouri court in 1846. He received financial assistance from the son of his previous owner, Peter Blow. Scott claimed that his presence and residence in free territories required his emancipation. In June 1847, Scott’s case was dismissed because he had failed to provide a witness testifying that he was in fact a slave belonging to Eliza Emerson.

The judge granted Scott a new trial which did not begin until January 1850. While the case awaited trial, Scott and his family were placed in the custody of the St. Louis County Sheriff, who rented out the services of Scott, placing the rents in escrow. The jury found Scott and his family legally free. Emerson appealed to the Supreme Court of Missouri; she had moved to Massachusetts and transferred advocacy of the case to her brother, John F. A. Sanford. November 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the jury’s decision, holding the Scotts as legal slaves.

Scott sued in federal court in 1853. The defendant at this point was Sanford, because he was a resident of New York, having returned there in 1853; the federal courts could hear the case under diversity jurisdiction provided in Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution. Judge Robert Wells directed the jury to rely on Missouri law to settle the question of Scott’s freedom. Since the Missouri Supreme Court had held Scott was a slave, the jury found in favor of Sanford. Scott then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The decision began by concluding that the Court lacked jurisdiction in the matter because Scott had no standing to sue in Court, as all people of African descent, were found not to be citizens of the United States. The decision is often criticized as being obiter dictumbecause it went on to conclude that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories, and slaves could not be taken away from their owners without due process.

The decision was fiercely debated across the country. Abraham Lincoln was able to win the presidential election in 1860 with the hope of stopping the further expansion of slavery. The sons of Peter Blow purchased emancipation for Scott and his family on May 26, 1857. Their freedom was national news and was celebrated in northern cities. Scott worked in a hotel in St. Louis and died of tuberculosis only eighteen months later.

The Dred Scott decision represented a culmination of what was considered a push to expand slavery. Southerners argued that they had a right to bring slaves into the territories, regardless of any decision by a territorial legislature on the subject. The expansion of the territories and resulting admission of new states was a loss of political power for the North. It strengthened Northern slavery opposition, divided the Democratic Party on sectional lines, encouraged secessionist elements among Southern supporters of slavery to make bolder demands, and strengthened the Republican Party.

3.3 – Dual Federalism: From the Civil War to the 1930s

America functioned under dual federalism until the federal government increased influence after the Civil War.

Dual federalism is a theory of federal constitutional law in the United States where governmental power is divided into two separate spheres. One sphere of power belongs to the federal government while the other severally belongs to each constituent state. Under this theory, provisions of the Constitution are interpreted, construed and applied to maximize the authority of each government within its own respective sphere, while simultaneously minimizing, limiting or negating its power within the opposite sphere. Within such jurisprudence, the federal government has authority only where the Constitution so enumerates. The federal government is considered limited generally to those powers listed in the Constitution.

The theory originated within the Jacksonian democracy movement against the mercantilist American system and centralization of government under the Adams administration during the 1820s. With an emphasis on local autonomy and individual liberty, the theory served to unite the principles held by multiple sectional interests; the republican principles of northerners, the pro-slavery ideology of southern planters, and the laissez-faire entrepreneurialism of western interests. President Jackson used the theory as part of his justification in combating the national bank and the Supreme Court moved the law in the direction of dual federalism. The Court used the theory to underpin its rationale in cases where it narrowed the meaning of commerce and expanded state authority through enlarging state police power.

Andrew Jackson: Andrew Jackson, who put forth the theory of dual federalism.

The Democratic-Republicans believed that the Legislative branch had too much power and was unchecked, the Executive branch had too much power and was unchecked, and that a Bill of Rights should be coupled with the Constitution to prevent a dictator from exploiting citizens. The federalists argued that it was impossible to list all the rights, and those that were not listed could be easily overlooked because they were not in the official Bill of Rights.

After the Civil War, the federal government increased in influence greatly on everyday life and in size relative to state governments. The reasons were due to the need to regulate business and industries that span state borders, attempts to secure civil rights, and the provision of social services. National courts now interpret the federal government as the final judge of its own powers under dual federalism.

3.4 – The New Deal: Cooperative Federalism and the Growth of National Government

Cooperative federalism is a concept of federalism where national, state and local governments interact cooperatively and collectively to solve common problems, rather than making policies separately but more or less equally or clashing over a policy in a system dominated by the national government. This concept arose after dual federalism in the United States in the 1930s.

In the American federal system, there are limitations on national government’s ability to carry out its policies through the executive branch of state governments. There are significant advantages in a federal system to obtain state assistance in the local implementation of federal programs. Implementing programs through national employees would increase the size and intrusiveness of the national government and local implementation may assure the programs are implemented taking local conditions into account. Congress often avoids the adoption of completely nationalized programs by creating a delivery system for federal programs and by motivating compliance—threatening states that they will pose power over the regulated area completely.

Congress of the United States: The Congress Building of the United States is the seat of national or federal government which governs cooperatively with state and local government.

While the federal system places limits on the ability of the national government to require implementation by a state executive branch or its local political subdivisions, that limitation does not apply in the same way to state judicial systems. This is because the founders understood that state courts would be courts of general jurisdiction, bound to apply both state and federal law and because the state courts adjudicate cases between citizens who are bound to comply with both state and federal law. When Congress seeks to establish federal legislation that governs the behavior of citizens, they are free to choose among three judicial enforcement paradigms. It may open both federal and state courts to enforcement of that right, by specifically providing concurrent jurisdiction in the federal courts. It may grant exclusive jurisdiction to the federal courts, or it may choose to leave enforcement of that right to civil dispute resolution among parties in the state court.

4 – Federalism Today

Federalism today has its roots extending back to the 1860s.

4.1 – Introduction

Page One of the 14th Amendment: The Supreme Court began applying the Bill of Rights to the states during the 1920s even though the Fourteenth Amendment had not been represented as subjecting the states to its provisions during the debates that preceded ratification of it.

The modern federal apparatus owes its origins to changes that occurred during the period between 1861 and 1933. While banks had long been incorporated and regulated by the states, the National Bank Acts of 1863 and 1864 saw Congress establish a network of national banks that had their reserve requirements set by officials in Washington. During World War I, a system of federal banks devoted to aiding farmers was established, and a network of federal banks designed to promote home ownership came into existence in the last year of Herbert Hoover’s administration. Congress used its power over interstate commerce to regulate the rates of interstate (and eventually intrastate) railroads and even regulate their stock issues and labor relations, going so far as to enact a law regulating pay rates for railroad workers on the eve of World War I. During the 1920s, Congress enacted laws bestowing collective bargaining rights on employees of interstate railroads and some observers dared to predict it would eventually bestow collective bargaining rights on workers in all industries. Congress also used the commerce power to enact morals legislation, such as the Mann Act of 1907 barring the transfer of women across state lines for immoral purposes, even as the commerce power remained limited to interstate transportation—it did not extend to what were viewed as intrastate activities such as manufacturing and mining.

As early as 1913, there was talk of regulating stock exchanges, and the Capital Issues Committee formed to control access to credit during World War I recommended federal regulation of all stock issues and exchanges shortly before it ceased operating in 1921. With the Morrill Land-Grant Acts Congress used land sale revenues to make grants to the states for colleges during the Civil War on the theory that land sale revenues could be devoted to subjects beyond those listed in Article I Section 8 of the Constitution. On several occasions during the 1880s, one house of Congress or the other passed bills providing land sale revenues to the states for the purpose of aiding primary schools. During the first years of twentieth century, the endeavors funded with federal grants multiplied, and Congress began using general revenues to fund them—thus utilizing the general welfare clasues’s broad spending power, even though it had been discredited for almost a century (Hamilton’s view that a broad spending power could be derived from the clause had been all but abandoned by 1840).

During Herbert Hoover’s administration, grants went to the states for the purpose of funding poor relief. The Supreme Court began applying the Bill of Rights to the states during the 1920s even though the Fourteenth Amendment had not been represented as subjecting the states to its provisions during the debates that preceded ratification of it. The 1920s also saw Washington expand its role in domestic law enforcement. Disaster relief for areas affected by floods or crop failures dated from 1874, and these appropriations began to multiply during the administration of Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921). By 1933, the precedents necessary for the federal government to exercise broad regulatory power over all economic activity and spend for any purpose it saw fit were almost all in place. Virtually all that remained was for the will to be mustered in Congress and for the Supreme Court to acquiesce.

4.2 – New Federalism and State Control

New Federalism is a philosophy that focuses on states’ rights.

Louis Brandeis: Brandeis’ opinion in New Ice Co. set the stage for new federalism.

New Federalism is a political philosophy of devolution, or the transfer of certain powers from the United States federal government back to the states. Unlike the eighteenth-century political philosophy of Federalism, the primary objective of New Federalism is some restoration of autonomy and power that the states lost as a consequence of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. It relies upon a Federalist tradition dating back to the founding of the country, as well as the Tenth Amendment.

As a policy theme, New Federalism typically involves the federal government providing block grants to the states to resolve a social issue. The federal government then monitors outcomes but provides broad discretion to the states for how the programs are implemented. Advocates of this approach sometimes cite a quotation from a dissent by Louis Brandeis in New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann: “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

From 1937 to 1995, the United States Supreme Court did not void a single Act of Congress for exceeding Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitution. They held that anything that could conceivably have even a slight impact on commerce was subject to federal regulation. It was thus seen as a (narrow) victory for federalism when the Rehnquist Court reined in federal regulatory power in United States v. Lopez (1995) and United States v. Morrison (2000).

The Supreme Court wavered, however, in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), holding that the federal government could outlaw the use of marijuana for medical purposes under the Commerce Claue even if the marijuana was never bought or sold, and never crossed state lines. How broad a view of state autonomy the Court will take in future decisions remains unclear.

The Supreme Court wavered, however, in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), holding that the federal government could outlaw the use of marijuana for medical purposes under the Commerce Clause even if the marijuana was never bought or sold, and never crossed state lines. How broad a view of state autonomy the Court will take in future decisions remains unclear.

4.3 – The Devolution Revolution

The devolution revolution was a movement started by Reagan in the 1980s that involves the gradual return of power to the states.

The term “devolution revolution” came from the Reagan ideology and is associated with New Federalism. New Federalism, which is characterized by a gradual return of power to the states, was initiated by President Ronald Reagan (1981–1989) with his “devolution revolution” in the early 1980s, and lasted until 2001. The primary objective of New Federalism, unlike that of the eighteenth-century political philosophy of Federalism, is the restoration to the states of some of the autonomy and power that they lost to the federal government as a consequence of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Previously, the federal government had granted money to the states categorically, limiting the states to use this funding for specific programs. Reagan’s administration, however, introduced a practice of giving block grants, freeing state governments to spend the money at their own discretion.

Ronald Reagan: The devolution revolution was an ideology supported by Ronald Reagan.

New Federalism is sometimes called “states’ rights,” which is a theory in U.S. politics that refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. Its proponents usually eschew the idea of states’ rights because of its associations with Jim Crow laws and segregation. Unlike the states’ rights movement of the mid-20th century which centered around the civil rights movement, the modern federalist movement is concerned far more with expansive interpretations of the Commerce Clause, as in the areas of medical marijuana (Gonzalez v. Raich), partial birth abortion (Gonzalez v. Carhart), gun possession (United States v. Lopez), federal police powers (United States v. Morrison, which struck down portions of the Violence Against Women Act), or agriculture (Wickard v. Filburn). President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) embraced this philosophy, and President George W. Bush (2001–2009) appeared to support it at the time of his inauguration.

4.4 – Judicial Federalism

Judicial federalism is a theory that the judicial branch has a place in the check and balance system in U.S. federalism.

Marbury v. Madison Placard: Marbury vs. Madison changed the role of the judicial branch in the federal system.

Judicial federalism relies on the fact that the judiciary has a place in the check and balance system within the federal government. Much of judicial federalism is dependent on judicial review as well as other acts defining the judiciary’s role in the U.S. government.

The first Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the lower federal courts and specified the details of federal court jurisdiction. Section 25 of the Judiciary Act provided for the Supreme Court to hear appeals from state courts when the state court decided that a federal statute was invalid or when the state court upheld a state statute against a claim that the state statute was repugnant to the Constitution. This provision gave the Supreme Court the power to review state court decisions involving the constitutionality of both federal and state statutes. The Judiciary Act thereby incorporated the concept of judicial review.

Judicial review in the United States refers to the power of a court to review the constitutionality of a statute or treaty or to review an administrative regulation for consistency with a statute, a treaty, or the Constitution itself.

The United States Constitution does not explicitly establish the power of judicial review. Rather, the power of judicial review has been inferred from the structure, provisions, and history of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court’s landmark decision on the issue of judicial review was Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which the Supreme Court ruled that the federal courts have the duty to review the constitutionality of acts of Congress and to declare them void when they are contrary to the Constitution. Marbury, written by Chief Justice John Marshall, was the first Supreme Court case to strike down an act of Congress as being unconstitutional. Since that time, the federal courts have exercised the power of judicial review. Judicial review is now a well settled doctrine. As of 2010, the United States Supreme Court had held some 163 Acts of the U.S. Congress unconstitutional.

Although the Supreme Court continues to review the constitutionality of statutes, Congress and the states retain some power to influence what cases come before the Court. For example, the Constitution at Article 3, Section 2, gives Congress power to make exceptions to the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. The Supreme Court has historically acknowledged that its appellate jurisdiction is defined by Congress. Therefore, Congress may have power to make some legislative or executive actions non-reviewable. This is known as jurisdiction stripping.

4.6 – The Shifting Boundary between Federal and State Authority

Modern tensions between the state and federal governments began in the 1960s.

In 1964, the issue of fair housing in California involved the boundary between state laws and federalism. California Proposition 14 overturned the Rumsford Fair Housing Act and allowed discrimination in any type of home sale. Martin Luther King Jr. and others saw this as a backlash against civil rights. Actor Ronald Reagan gained popularity by supporting Proposition 14, and was later elected governor of California. The U.S. Supreme Court ‘s Reitman v. Mulkay decision overturned Proposition 14 in 1967 in favor of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Conservative historians Thomas E. Woods, Jr. and Kevin R. C. Gutzman argue that when politicians come to power they exercise all the power they can get, in the process trampling states’ rights. Gutzman argues that the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions of 1798 by Jefferson and Madison were not only responses to immediate threats but were legitimate responses based on the long-standing principles of states’ rights and strict adherence to the Constitution.

Separate but Equal–Again?: Discrimination as supported by Proposition 14 concerned civil rights leaders that it would bring America back to the separate but equal days.

Another concern is the fact that on more than one occasion, the federal government has threatened to withhold highway funds from states that did not pass certain articles of legislation. Any state that lost highway funding for any extended period would face financial impoverishment, infrastructure collapse, or both. Although the first such action (the enactment of a national speed limit) was directly related to highways and done in the face of a fuel shortage, most subsequent actions have had little or nothing to do with highways and have not been done in the face of any compelling national crisis. An example of this would be the federally mandated drinking age of 21. Critics of such actions feel that when the federal government does this they upset the traditional balance between the states and the federal government.

More recently, the issue of states’ rights has come to a head when the Base Realignment Closure Commission (BRAC) recommended that Congress and the Department of Defense implement sweeping changes to the National Guard by consolidating some Guard installations and closing others. These recommendations in 2005 drew strong criticism from many states, and several states sued the federal government on the basis that Congress and the Pentagon would be violating states’ rights should they force the realignment and closure of Guard bases without the prior approval of the governors from the affected states. After Pennsylvania won a federal lawsuit to block the deactivation of the 111th Fighter Wing of the Pennsylvania Air National Guard, defense and Congressional leaders chose to try to settle the remaining BRAC lawsuits out of court, reaching compromises with the plaintiff states.

Current states’ rights issues include the death penalty, assisted suicide, gay marriage, and the medicinal use of marijuana. The latter is in violation of federal law. In Gonzales v. Raich, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the federal government, permitting the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to arrest medical marijuana patients and caregivers. In Gonzales v. Oregon, the Supreme Court ruled that the practice of physician-assisted suicide in Oregon is legal. Nonetheless, states are obligated, under all circumstances, to respect, defend and abide by the requirements of the Constitution, especially the due process of law. These constitutional requirements, in short, must be extended to all citizens at all times.

Originally published by Lumen Learning – Boundless Political Science under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.