By Andrew Dickson

Author and Journalist

Introduction

Perhaps Sheridan’s greatest play, The School for Scandal is one of the supreme triumphs of 18th-century theatre and is sometimes described as the greatest comedy of manners in the English language. A crackling satire on ostensibly polite society, it is populated by a cast of hypocrites and schemers, and filled with dazzlingly sharp repartee – a major reason it has rarely been off the stage since 1777, the year it first opened. But despite its apparent lack of seriousness, the play is a thoroughly moral work, as well as a remarkable technical accomplishment. In the words of Thomas Moore, an early biographer: ‘it is the fate of Mr Sheridan … to gain credit for excessive indolence and carelessness, while few persons, with so much natural brilliancy of talents, ever displayed more art and circumspection in their display’.[1]

Early Life and Works

Drama was in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s blood: his father was an actor-manager and for a time ran Dublin’s Smock Alley Theatre, while his mother had gained some fame as a playwright and novelist. When the family moved to London in 1758, seven years after Richard’s birth, he attended Harrow School, before the Sheridan clan relocated once more, this time to Bath. Sheridan never returned to Ireland.[2]

Although the young Sheridan showed some interest in following in his parents’ footsteps and writing for the theatre, the most dramatic event of his 20s occurred offstage. In the early 1770s, he fell in love with a soprano – and noted beauty – called Elizabeth Ann Linley, despite the loud objections of both their families. When the couple eloped to France in 1772, the affair became a public scandal, particularly after Sheridan fought no fewer than two duels with a rival lover. Nonetheless, the pair could not be kept apart and they married officially the following spring.

They set up home in grand style in London that same year, 1773, but were cripplingly short of income. Ignoring his father’s wish that he should become a lawyer, Sheridan decided that the best solution would be for him to write a commercially successful play. In summer 1774, he began work on a comedy of manners that focused on a woman determined to marry for love rather than money – just one of numerous autobiographical references. The Rivals, as it was called, went into rehearsal at the Covent Garden Theatre that November.

Its first night was, infamously, a flop: one of the actors was drunk, and the playwright was forced to make hurried cuts to the script.[3] But following what he later described as these ‘prunings, trimmings and patchings’, the second performance was enthusiastically received, and Sheridan’s reputation was made. His next work, a comic opera called The Duenna, did even better, running for 74 performances. Again, it has teasing echoes of the playwright’s own life, featuring a plot in which two daughters conspire to escape tyrannical fathers and elope with their lovers.[4]

After the renowned actor-manager David Garrick announced his retirement from London’s other major theatre, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in 1774, Sheridan negotiated to take over Garrick’s share and run the building himself. He opened his first season in 1776 with revivals of Shakespeare’s As You Like It and plays by the Restoration comedian William Congreve. He also subjected John Vanbrugh’s comedy The Relapse (1696) to ‘a little wholesome pruning’, renaming it A Trip to Scarborough and producing it the following February.

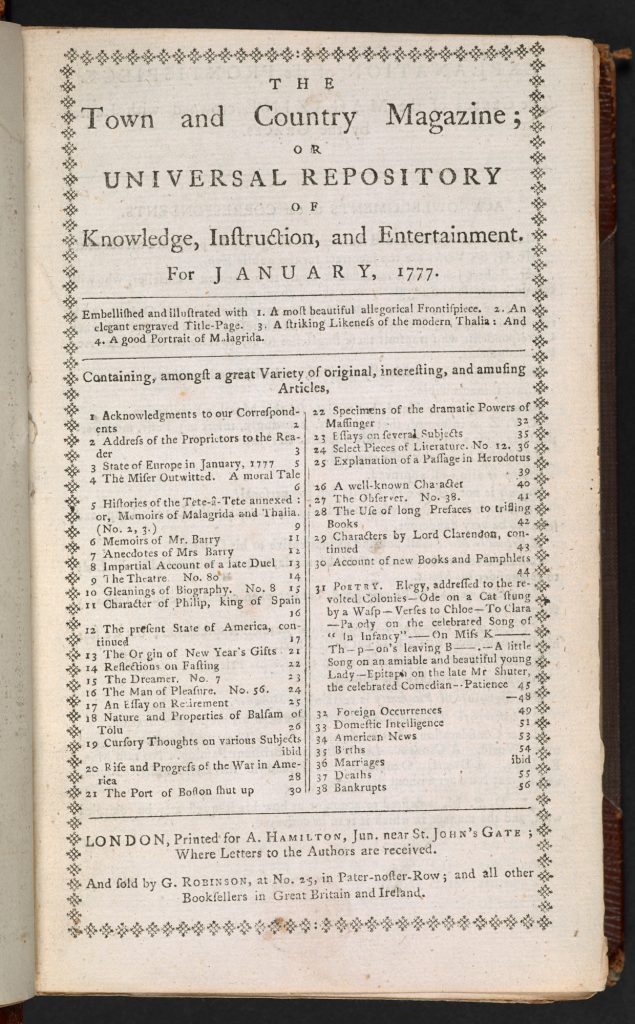

Even before these shows went on stage, Sheridan was at work writing a new comedy of his own, The School for Scandal, to mounting public anticipation. Despite the playwright’s struggles to get it finished – just a month before it opened, the Morning Chronicle sardonically reported that ‘each Actor in the Piece … is already in possession of a fourth part of his character’ – it finally reached the stage in May 1777.[5]

‘I Cannot Bear to Hear People Attacked behind Their Backs’

For his third major play, Sheridan demonstrated that he had not only learned from revising others’ work, but had also mastered his own craft (albeit not at once: he kept tinkering with the script in the months up to, and even after, the first production).[6]

Although The School for Scandal’s plot is original, it borrows heavily from the sexual and romantic hi-jinks of Restoration drama from a century earlier, and even glances back to the slick, cynical ‘city comedies’ written by Ben Jonson and other playwrights of the early 17th century.

The play opens in the upper reaches of fashionable London society, in what was then the present day. We observe as Lady Sneerwell conspires with the duplicitous Joseph Surface to break up the relationship between Joseph’s rakish but kindly brother Charles and a young virtuous lady named Maria. Joseph, naturally, fancies Maria for himself – although mainly for her money – while Lady Sneerwell has her own eye on Charles. When rumours spread that Charles has had an affair with a rich wife, Lady Teazle, catastrophe looms. Lady Teazle’s social circle forms the ‘school for scandal’, whose members, led by Lady Sneerwell, include Sir Benjamin Backbite, Crabtree and Mrs Candour; their shared purpose being to stir and feed gossip, and in doing so destroy the social reputation of others. This state of affairs is redressed by the unexpected arrival of Sir Oliver Surface, the rich uncle of Joseph and Charles, who assumes various disguises to test his nephews’ integrity. The truth is revealed when Joseph is caught attempting to seduce Lady Teazle and he is exposed as the hypocrite he is. Charles is vindicated, and love wins the day.

The play crackles with satirical wit, most of it aimed at the hypocrisy of the reputation-obsessed upper classes, particularly when it comes to relationships. As the names of its dramatis personae indicate (Sneerwell, Surface, Mrs Candour, Sir Benjamin Backbite, the dastardly henchman Snake), its characters are stock types, and would have been reassuringly familiar to Sheridan’s audience. What makes the play distinctive – and so enjoyable to watch – is its rapid-fire repartee, which has an energy that is impossible to resist. ‘I cannot bear to hear people attacked behind their backs’, proclaims the pious Mrs Candour early in the play, immediately following this with ‘By the bye, I hope ’tis not true that your brother Charles is absolutely ruined?’[7]

For her part, Lady Sneerwell is admirably clear about what drives her, at least when none of her victims are listening. As she says to Snake, ‘Wounded myself in the early part of my life by the envenomed tongue of slander, I confess I have since known no pleasure equal to the reducing others to the level of my own injured reputation’ (1.1.32–35). Although the line is comic, the point is deadly serious, like so much of the play: ‘slander’ has a genuinely corrosive effect.

Sheridan has many other targets, too, each of which is dispatched with glee. Early audiences would have realised that The School for Scandalis a parody of the so-called ‘sentimental comedies’ that had been hugely popular for at least 50 years. These were earnest dramas that portrayed essentially well-meaning characters triumphing against the odds (an example would be Richard Steele’s The Conscious Lovers from 1722). In The School for Scandal, Joseph is cast as a ‘man of sentiment’ with high moral virtues, though we quickly realise that he is nothing of the kind. Opposing him on this moral compass is Charles, who despite his spendthrift ways is one of the most thoroughly ‘good’ people in the piece.

The play is also, importantly, about theatre itself. Taking issue with the 18th-century idea that the stage offered mere popular entertainment (some critics claimed it could even be morally corrupting), Sheridan demonstrates that drama could hold up a mirror to the hypocrisies of real life. As the biographer Fintan O’Toole puts it, ‘Sheridan would show that the world of “fact” – the world as it appeared in the newspapers – was full of lies, while the inventions of the theatre could reveal a kind of truth’. Centuries before the term ‘fake news’ became current, Sheridan wanted to demonstrate the dangers of unfettered rumour – a genuine concern at the time, given the popularity of gossip columns in popular newspapers. The very first line of the play has Snake boasting to Lady Sneerwell that he has ‘inserted’ paragraphs in a gossip rag, exposing unlucky victims to public shame (1.1.3–5).

The Comedy on Stage

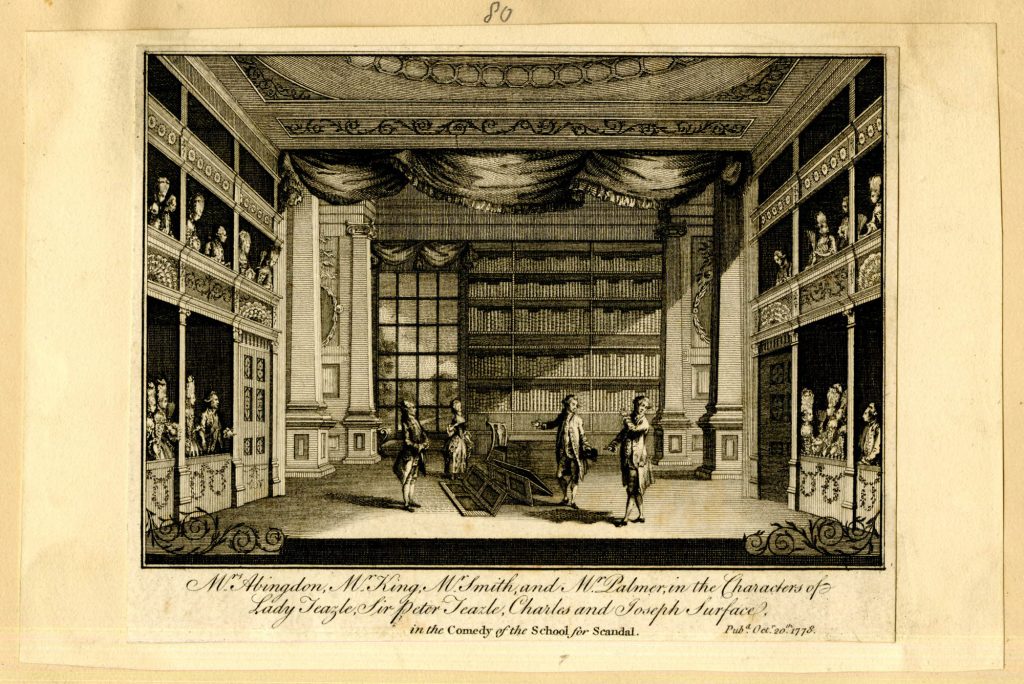

As numerous critics have observed, it’s difficult to get to grips with The School for Scandal by reading it. Like Sheridan’s other plays, it only truly comes alive on the stage. The writer and critic Charles Lamb astutely called this a ‘manager’s comedy’, and indeed Sheridan orchestrates the setting with a sure instinct for the resources of his theatre and the performers he wrote for (Frances Abington, the finest comedienne of the day, played Lady Teazle, with the silkily duplicitous John Palmer, known as ‘Plausible Jack’, taking the role of Joseph).[8]

Drury Lane was notable for featuring a ‘forestage’ that projected into the auditorium, something which enabled greater intimacy between actors and audience and was particularly useful for whispered ‘asides’ (a dramatic device in which a character confides in the audience, unheard by anyone else on stage). These are used to winning effect in The School for Scandal, as are comic ‘discovery scenes’ – Sheridan in fact coined the term – in which one or more characters hide from the other characters while remaining in full view of the audience.

No fewer than five scenes feature ‘discoveries’. Perhaps the funniest – and most important – is Act 4, Scene 3, which occurs in Joseph’s library and provides the climax of the play’s action. Joseph and Lady Teazle are flirting when her husband, Sir Peter, walks in, which means that Lady Teazle has to dash behind a screen – a physical symbol of Joseph’s deception. Lady Teazle is quickly followed by Sir Peter himself, who is desperate to avoid Charles and hides in a closet. Eventually, Charles discovers them both, to massive mutual embarrassment. This theatrical ‘reveal’ is metaphorical, too: Joseph is exposed as a hypocrite and scoundrel, Lady Teazle realises that her husband is racked by doubts about her fidelity, while it is the honourable Charles who uncovers them all, along with the truth. A riot of verbal asides and sight gags (visual jokes), the scene is long and remarkably elaborate to stage, though hugely fun to watch. It must have been impressive in the original 1777 production, which featured lavish costumes, bright stage lighting and painted ‘flats’ by the artist Philip James de Loutherbourg designed to look just like a real library.[9]

Politics and Public Life

The School for Scandal was a triumphant success – so much so that one report has it that a man passing by Drury Lane, hearing the great roar of the audience, assumed that the building was about to collapse and ran for his life.[10] The production eventually made the astonishing figure of £15,000 at the box office (well over £1m in today’s money), and by the end of the century it had been performed more than any other play in London. It was also rapidly translated into other languages, including German and French (in Russia, the theatre-loving Catherine the Great commissioned her own version, and in the recently independent America it was said to be George Washington’s favourite comedy).

But, despite his remarkable success as a playwright-producer, Sheridan retained an ambivalent attitude to the theatre. His later plays The Camp (1778) and The Critic (1779) were both commercially successful, but on a lesser scale than before, and although he and his business partners demolished and rebuilt Drury Lane in 1794, making the auditorium more luxurious and larger, Sheridan became increasingly obsessed by politics. In 1780 he was elected to Parliament and was then appointed secretary to the Treasury. He never wrote another play, deploying his considerable verbal abilities in parliamentary debates instead, notably playing a starring role in the trial of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of India, in the late 1780s (Sheridan famously denounced Hastings in a painstakingly crafted speech that lasted several days).

In 1809, catastrophe occurred when the Drury Lane Theatre burned down; this ruined Sheridan financially, and two years later he lost his parliamentary seat. Though The School for Scandal was a continued success and frequently revived, in its own way it came back to haunt him. Despite his successes as a politician, Sheridan was never able to escape the charge that in public life he was exactly the kind of duplicitous schemer he had represented in the play.

Notes

- Thomas Moore, Memoirs of the Life of the Right Honourable Richard Brinsley Sheridan (London, 1825). Text available online at: <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6741/6741.txt>

- For details of Sheridan’s life, the best short – and freely accessible – account is the Encyclopedia Britannica entry <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Richard-Brinsley-Sheridan>. Sheridan’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography by A Norman Jaffares, updated in 2008, is also well worth consulting, while the best full biography is Fintan O’Toole’s A Traitor’s Kiss: The Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan (London: Granta, 1997).

- Simon Reade offers an entertaining retelling in ‘The Scourge of Bath’, The Guardian, (14 May 2004) <https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2004/may/15/theatre>.

- O’Toole’s account of these plays’ composition is the best, and is particularly insightful on their autobiographical resonances (A Traitor’s Kiss, pp. 85–101).

- Cited in Dane Farnsworth Smith and M L Lawhon, Plays About the Theatre in England, 1737–1800 (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1979).

- F W Bateson summarises the difficulties of deciding which text is final in the introduction (p. xxxv) to his edited edition of the play (for which see below).

- Richard Brinsley Sheridan, The School for Scandal, ed. by F W Bateson (London: Ernest Benn, 1979), 1.1.233–37. All citations to this edition.

- Charles Lamb, ‘On the Artificial Comedy of the Last Century’, in Essays of Elia (1823).

- Bateson’s edition of the play is good on details of casting and staging; see pp. xxiii–xxxiii.

- The story is related in Linda Kelly, Richard Brinsley Sheridan: A Life (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1997), p. 77.

Originally published by the British Library, 06.21.2018, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.