Looking beyond an initial impression to dissect what is happening beyond the surface in particular historical contexts.

By Dr. Julia M. Gossard

Assistant Professor of History

Utah State University

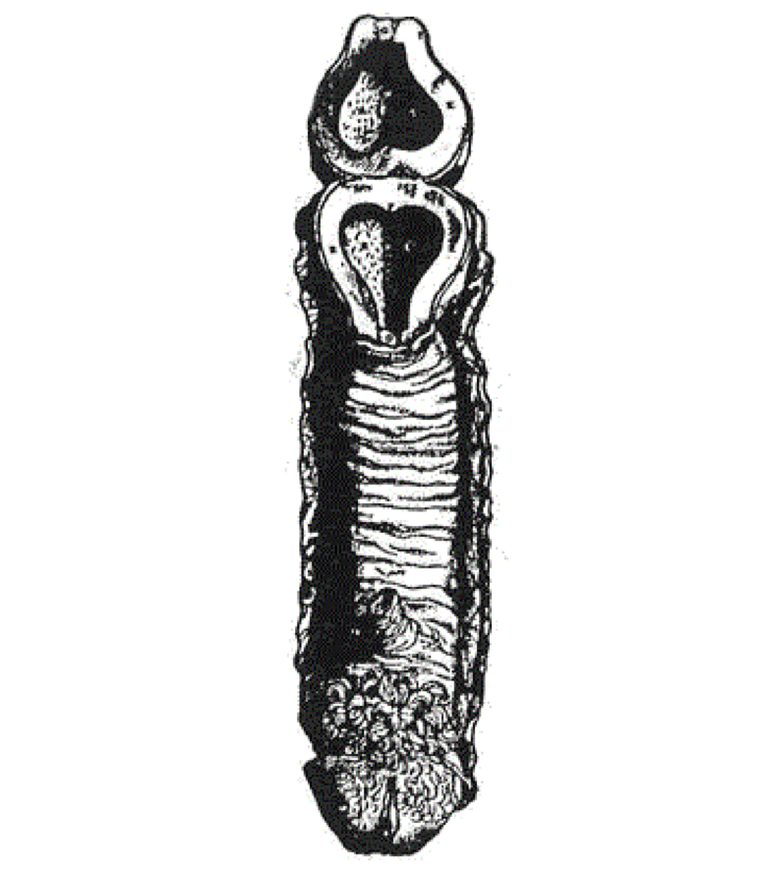

On the first day of my class, ‘Witches, Workers, & Wives,’ I showed students an image from Book 5 of Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (On the fabric of the human body in seven books).At first glance, my students assumed that the image in front of them was a penis. A few of the more observant students started to notice some of the image’s more curious features. After letting some of the giggles subside I asked them, “Is this a penis?” While most students stared at me in disbelief that I would even ask such an obvious question, a few brave students spouted the right answer: this was not a penis. In fact, it was an anatomical drawing of the female reproductive system from 1543. My students started arguing with me, passionately defending their views of this image as a penis. “That is so clearly a dick!” and “I don’t see how that’s NOT a penis!” rang out. Calming them, I read Baldasar Heseler’s description of Vesalius’ drawing, “the organs of procreation are the same in the male and the female…for if you turn the scrotum, the testicles, and the penis inside out, you will have all the genital organs of the female.” Silence permeated the classroom.

Presenting Vesalius’ “penis-vagina” (as many students took to calling it) on the first day of class immediately primed students to dissect early modern social constructions of gender and sexuality. It was an idea I got from watching my doctoral advisor, Julie Hardwick, do a similar exercise. The lesson provided an opportunity to examine how a primary source can be open to various, sometimes conflicting, interpretations by scholars.

After students composed themselves from the initial shock, I explained how the image and Heseler’s description form the basis of Thomas Laqueur’s “one-body” model thesis.Until the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century, Laqueur contends that Europeans commonly believed that men and women shared the same sexual organs. This one body resulted in two sexes: male with a penis and female with a vagina. Aristotle is to thank for this scientific thought since he theorized that women were imperfect men. Women were “a deformity but one which occurs in the ordinary course of nature.” According to Laqueur, sixteenth-century science seemed to prove Aristotle’s findings when autopsies on women dissected the clitoris and determined that women must just have two penises. This was part of women’s imperfection.

The idea was well ensconced in European culture, too, as much folklore told of young women who jumped too hard while skipping stones only to have their uteruses pop out and become penises. Hearing this old wives’ tale, one of my students commented that early modern Europeans possessed a nascent understanding of gender fluidity. This folktale acknowledged that it was possible, albeit rare, to change both sex and gender. This idea encouraged my students to discuss how knowledge about gender, sex, and the body was far from fixed throughout history.

To complicate this for my students further, I had them read selections from John Knox’s political treatise attacking Mary Tudor and Mary Queen of Scots, “The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women.” Knox seems to encapsulate the one-body model when he argues, “to promote a woman to bear rule, superiority, dominion, or empire above any realm or nation is repugnant to nature; contumely to God; [and] the subversion of good order.” Women’s submission, then, was part of the divine, natural order that justified patriarchal control. Women were considered mutated men, unfit to rule, to own property, or to exist outside of the confines of patriarchal control. But, as Mary Tudor, Mary Queen of Scots, Elizabeth I, and Christina of Sweden, to name a few, all demonstrate, the one-body model was not all-powerful. These women were all able to rule, often calling upon their female characteristics either as virgins, mothers, or nurturers, to justify their authority and subversion of patriarchy.

This beautifully transitioned discussion for the next class session to focus on the other interpretation of Vesalius’ image – that of the womb. Pushing back against Laqueur, Helen King’s The One-Sex Body on Trialargues that one-sex and two-sex body models have existed alongside each other since antiquity. I presented her critique of Laqueur’s thesis, pointing to Vesalius’ image not as a penis-vagina, but as an independent organ: the womb. With increased scientific and medical interest in the sixteenth century in women’s diseases, King argues that early modern society recognized that women’s bodies and sexual organs were, in fact, separate from men’s. But, women’s bodies were still inferior to men’s. Ideas about the frailty and weakness of women’s bodies both influenced and were informed by social constructions of femininity, masculinity, and patriarchal power to the modern period.

These two theories, enabled by Vesalius’ illustration, were essential starting points for my students to understand how gender inequalities were both justified and normalized for centuries. My students spent fifteen weeks analyzing the historical changes and continuities in European and Atlantic notions of gender, sexuality, politics, society, and economics from roughly 1500 to 1800. We focused on the many ways early modern women and children pushed back against patriarchy and coverture to negotiate their own lives, often at the grassroots level in the household, in the market, or on the shop floor. We came back to Vesalius’ image on the last day of class to remind ourselves of how important it is to look beyond an initial impression to dissect what is happening beyond the surface in particular historical contexts.

Originally published by NOTCHES: (re)marks on the history of sexuality, 03.27.2018, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.