Were the circumstances of London life around 1500 more favourable to domestic stability and wellbeing?

By Dr. Vanessa Harding

Professor of London History

Birkbeck University of London

Introduction

In the 1970s Caroline Barron and the late Valerie Pearl began to teach an undergraduate paper, ‘London: urban society, 1400–1700’, as part of the University of London’s BA degree in history. After Valerie Pearl left for Cambridge, Caroline reformulated the paper as ‘London: urban society, 1400–1600’ and continued to teach it until, and even beyond, her retirement. Literally hundreds of students must have taken this paper over the years, including several of the contributors to this volume; some of us have also taught it, either alone or in collaboration with her, and benefited from its wide-ranging approach and content. The syllabus evolved over the years, reflecting changing scholarship and new trends and interests, but its long focus remained, embodying the view that ‘medieval London’ did not end in 1485 or 1500 or even 1540 and emphasizing that social, political and economic change needed to be considered in perspective as well as in detail. The long view and comparative context are important as we consider ‘medieval Londoners’ and their characters; and experiences and points of reference well outside the period may not be out of order.

By way of complement to biographical and prosopographical approaches to ‘medieval Londoners’, this article takes a more general look at an important aspect of medieval Londoners’ lives: marriage and family, including their demographic chances. It concentrates on Londoners of what would come to be called the ‘middling sort’: citizens and their families, those who left traces in the records as litigants, testators, parishioners and local officials. All the Londoners studied in this volume lived their lives in the social and demographic realities discussed here; and if some escaped the problems personally, London’s close-knit neighbourhoods and communities ensured awareness of others’ lives and issues.

This article focuses on the family in the period around 1500, partly for reasons of source survival and partly to avoid too generalized a picture. However, the agenda for the enquiry was prompted by looking at a later period, c.1700, when marriage and family life were believed to be in some kind of crisis.1 Contemporary writers and more recent historians have singled out for comment a number of problems in the 1690s, ranging from the less serious but indicative – such as declining observance of official marriage requirements – to the more serious ones of marital breakdown and child abandonment, vagrancy and criminality. Crisis in the family was set against, and in part explained by, a sense of crisis in society as a whole.2 As with other themes such as the social and economic rights of women, the vigour of civic institutions or popular religion, posited decline or crisis in the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries seems to suppose some more golden period in earlier decades or centuries.3 But some at least of these issues can be identified in later medieval London, along with a significant level of concern: sexual misconduct; questionable marriage practices; licentious behaviour; irreligion (whether failures of the clergy or heretical beliefs); coupled with seemingly oppressive taxation and concerns about immigration. Was the London family in the early Tudor period any more robust, or less stressed, than in the late Stuart age? Were the circumstances of London life around 1500 more favourable to domestic stability and wellbeing? And were the concerns expressed around 1700 less a sign of particular crisis than a reflection that marriage and the family are always a focus of anxiety and pessimistic commentary?

The documentation for the enquiry is quite rich and varied and the secondary literature extensive. This article draws on individual lives, such as those detailed in Caroline Barron’s and Anne Sutton’s Medieval London Widows,4 and on wills, a particular interest of the honorand of this volume. It benefits enormously from studies using contemporary London church court records, notably by Richard Wunderli and Shannon McSheffrey.5 Records of the city’s orphanage procedures were another important source.6

London in 1500

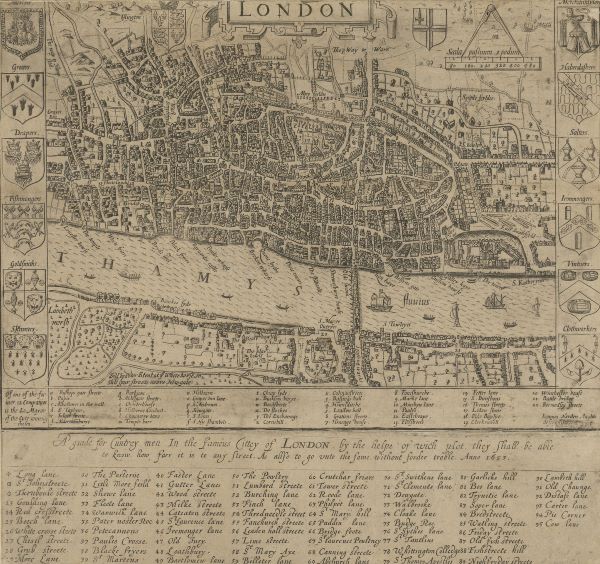

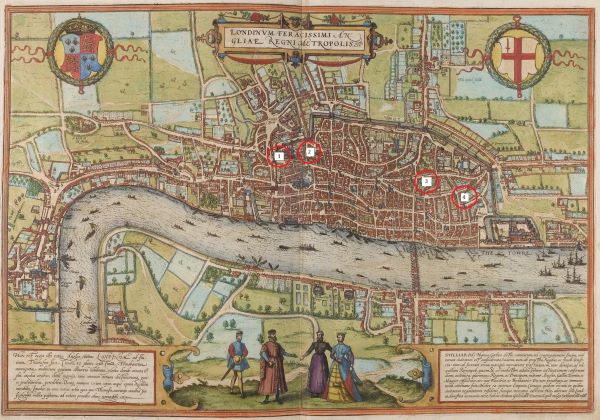

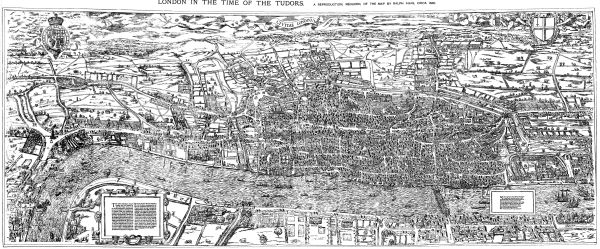

There are specific features of London’s society and economy in the period around 1500 which need to be borne in mind in any consideration of the family and family structures. In the long term, between c.1380 and 1550, the framing dates for which we can make population estimates, London’s population grew quite substantially, marking a much more positive trend than the country as a whole and the urban sector in general. England’s population in the mid sixteenth century may have been at around the same level as in the 1370s, or lower; Alan Dyer’s figures for the urban experience suggest that the total population of the fifty-seven largest provincial towns declined by twelve per cent between 1377 and 1524.7 London, however, had increased in size over the same period. The total population of the city, Southwark and Westminster in 1380 was probably around 40–45,000; in 1550 the population of the built-up area may have been around 60–70,000, possibly as much as 80,000, its probable maximum before the Black Death.8 It is unlikely that this represents a slow but steady growth over a long period; it is possible that population growth was negligible or even negative until the second half of the fifteenth century, but evidence from rents suggests that it was accelerating quite rapidly before the mid sixteenth century.9 It seems likely, therefore, that the population of London in 1500 was not much greater than it had been in 1380 – perhaps in the region of 50–55,000 – and it seems fair to assume that the early Tudor city was less crowded than before the Black Death, with more open space between and behind buildings as minor or unlettable properties were allowed to decay.10 Although London had begun to spread, it was still a comparatively small and compact city, surrounded by fields and gardens.11 John Stow’s famous recollection of his youth in the 1530s – being sent to fetch milk hot from the cow in Goodman’s Fields a few minutes’ walk from Aldgate – recorded a London soon to disappear.12

Given high urban mortality rates, London’s demographic growth depended on migration. In the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, young men were flooding to London to take up apprenticeships in the city companies, as the city’s employment opportunities expanded. Between 1486 and 1491 the Merchant Taylors’ Company, clearly expanding as the London cloth industry grew, enrolled on average sixty-eight apprentices a year; of those whose place of origin can be traced most came from the north Midlands and beyond. Lesser companies may have had smaller recruitment fields, but the range of London’s reach is still remarkable.13 The only surviving city freedom registers for the sixteenth century, for 1551–3, record 1,100 young men entering the freedom of the city in those years, most of whom would have been bound apprentice in the mid 1540s or earlier. Only seventeen per cent came from London or had London fathers; the rest were migrants from the provinces and not predominantly the home counties, either.14 Despite these numbers, however, London’s structures of apprenticeship and guild control offered young male migrants a path to citizenship and establishment, providing training, discipline, a framework of legal protection and the creation of a network of associates and possible patrons. Apprentices were socialized within a paternalistic framework of household order and invested in the ethos of citizenship and civic authority.

Not all migrants necessarily wished, or could afford, to obtain citizenship. The medieval city distinguished between citizens and ‘foreigns’, the latter comprising both settled Londoners who were not citizens and English migrants who had likewise not become citizens. Foreigns were meant to work in unskilled trades only and were debarred from participation in local democracy and administration, though they were not exempt from taxation.15 In practice, given a shortage of labour in the fifteenth century, many citizen craftsmen employed or worked alongside foreigns, who made an essential contribution to the city’s economy.16 It is often hard to tell whether the ordinary Londoners mentioned in many sources were citizens or not. As London expanded, however, in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, craft guilds and companies began to police the rules restricting foreigns’ activities more closely, complaining in 1494 of the influx of ‘Foreyns journeymen’ who took their employment without acknowledging guild control.17 Part of the problem was the high level of the guilds’ own entry fees, which deterred men from joining guilds and taking up citizenship. The city perceived the advantages of bringing more of the population into citizenship and, first on its own and then in obedience to acts of parliament in 1531 and 1536, ordered a reduction in entry fees. This seems to have resulted in a major increase in guild membership and citizenship – annual admissions to twelve companies increased by sixty-nine per cent over the next two decades. By the middle of the sixteenth century ‘approximately three-quarters of London’s men were freemen’.18

Women migrants to London are often hard to trace: they did not often obtain apprenticeships and an individual’s entry to metropolitan society is not usually recorded. If there was a shortage of labour in fifteenth-century London, it is likely that female migrants would be drawn in to help meet demand and there are some examples of country-born girls apprenticed in London.19 There were numerous female domestic servants and it would be surprising if many of these were not migrants. But the huge demand for domestic servants that developed in later seventeenth-century London was not yet apparent. Not only was London much smaller, but the traditional family economy of household/workshop production may have limited the need for hired female labour.20

Migrants to London were clearly drawn by its opportunity-rich society and economy. In the second half of the fifteenth century London began to capture an increasing proportion of England’s export trade, especially in cloth, as this concentrated on the London-Antwerp axis. In 1450 about forty per cent of the wool export trade passed through London and just over forty per cent of cloth exports. By 1500 London was exporting about the same amount of wool, but its annual cloth exports had risen from 17,000 cloths in 1450 to 44,000, a rise of 150 per cent, or nearly sixty per cent of a rapidly rising national total. By 1520 London cloth exports had reached 63,000, or sixty-five per cent of the total; by 1550, at 112,000 cloths a year, they constituted nearly ninety per cent of the country’s total. The annual value of London’s import trade likewise rose from about £50,000 in the 1470s to c.£80,000 around 1500 and c.£140,000 in the 1530s.21 Huge fortunes were being made, by London Merchant Adventurers in particular, and if this did not necessarily percolate through London society – since the bulk of the trade was essentially in undyed broadcloths woven outside London – it nevertheless had some impact. By the 1520s London’s contribution to direct taxation was ten times that of the next English city, Norwich, and equal to the combined assessment of more than thirty provincial towns.22

For the ordinary artisan, the economic situation must also have seemed good. Wages had stabilized at a fairly high level following a century of labour shortage. In the second half of the fifteenth century a craftsman’s or labourer’s wage bought more than at any time in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. And although prices were rising, the drift was gradual: only twenty-two per cent between the 1490s and the early 1540s, or about half a per cent per annum.23 London wages were normally a quarter to a third higher than in the provinces, an obvious attraction to potential migrants, and this differential was retained even as the population began to grow.24

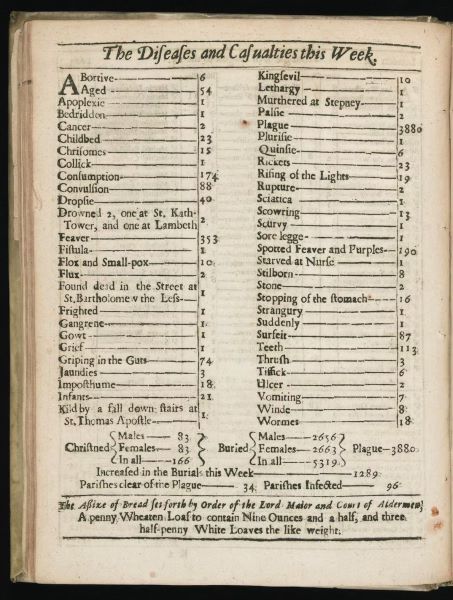

Early Tudor London certainly had its problems. Poverty and disease existed, and vagrancy. In 1518 the aldermen issued 772 licences to beg to people ‘so impotent, aged, feeble, or blind that they are not able to get their living by labour and work’.25 This figure can only represent a portion of the poor, limited to those seeking aid and thought to deserve it, but even so Steve Rappaport thought it indicated a poverty level of about six per cent, significantly less than the ten to twelve per cent indicated by surveys in the mid and late sixteenth century.26 Henry VII’s foundation of the Savoy hospital in 1505 significantly increased hospital provision in London beyond that offered in the still-extant older foundations. It was a fairly generously endowed attempt to deal with both poverty and sickness as social problems: offering accommodation to a hundred poor men, it provided beds, linen, medicines, nursing care and professional medical attendance.27 Despite being quite well provided with hospitals, London was not a healthy place to live. Mortality is hard to calculate with any certainty and we may underestimate the severity of the late medieval epidemics because they fall between the devastation of the fourteenth-century plagues and the impressive documentation of the plagues of the 1550s and later. Numbers of wills proved – the nearest indication of elevated mortality totals – spiked in 1479, 1498–1501, 1504, 1513, 1518 and 1521.28 Some of these epidemics were plague, but the sweating sickness first hit England in 1485, recurring in 1508, 1517, 1528 and 1551.29 We cannot count the dead in these epidemics, but contemporary writings give some sense of the impact of ‘pestilence’. The Great Chronicle reports that in the 1479–80 epidemic there was ‘an huge mortalyte & deth of people … To the grete mynysshyng of the people of all maner of agys’; in 1501 there was again ‘grete deth In London and othir partis of this Realm’.30 Testators referred to ‘this present time of sickness’ and made fall-back provision in case their appointed executors should not survive.31 Early Tudor London was not all rosy, but arguably many aspects of life there were better than they were to be one or two centuries later.

Sex and Marriage

If the social problems of the 1690s identified by late seventeenth-century commentators were blamed in part on wider economic and moral issues, do the somewhat more favourable conditions of life in London c.1500 mean that it was free from similar problems? Were the prospects for a stable and happy domestic and family life significantly better?

If we start with irregular marriage practices, then these can certainly be found in fifteenth-century London. One seventeenth-century problem was the increasing privacy of marital contracts. Publicity – as in the publication of banns and the performance of the marriage service in the couple’s church – was an important safeguard against dubious or irregular marriages and against the possibilities of self-divorce and bigamy. But an increasing number of couples were seeking marriage by licence in the later seventeenth century and there were numerous locations where marriages could be made legally but clandestinely. Literally thousands of couples chose to be married not in their parish church but in one of a handful of privileged parishes or in the liberty of the Fleet. The result was that a person’s marital status might be confused and could more easily be concealed and there is plenty of testimony to suggest that this happened.32

In early Tudor London irregularities and uncertainties centred on the mismatch between customary practices, legal requirements and the Church’s pressure for oversight of all marriages. Customary marriage, in which the right words said anywhere were enough to establish an indissoluble bond, had not yet been universally replaced by Church marriage, in which the making of the contract was supervised and validated by the presence of clergy and community. Consequently, there was some space for dispute about whether a valid marriage had been contracted or not; there were more opportunities for contest, denial and evasion if the marriage had not been solemnized in a church and before reliable witnesses. And as Shannon McSheffrey has pointed out, there were ‘inherent tensions’ between the individual’s freedom to contract a binding marriage and ‘the societal pressures to marry for family advantage and according to community norms’.33

The London church courts heard a number of cases in which the parties sought a ruling on whether a valid marriage existed. Both women and men could be the suitor or complainant. Agnes Whitingdon sued John Ely in 1487. She claimed a valid marriage had been contracted; he said that he had talked about it, but only conditionally, until he knew how much her father (who was not at the time in London) would give her. Agnes’s witnesses, on the other hand, testified that he had spoken words of present consent, ‘by my faith and troth, … I take you to my wife’, one evening in the shop of Agnes’s employer; and further that he had offered her the clothes of his deceased wife and ordered a wedding gown for her.34 In a case fifteen years earlier Rose Langtoft had contested Robert Smyth’s claim that a valid marriage existed between them. According to Robert’s witnesses, she spoke the words of consent actually in the sickroom of a neighbour’s wife. Rose denied this and brought witnesses to say she could not have been in the place and at the time Robert’s witnesses alleged she made the promise because she had not left the shop all afternoon. Subsequently, however, she relented – how willingly we do not know – and admitted she had so spoken and was therefore bound.35

Wunderli counted sixty-three ‘validation’ cases in the commissary court in the three years 1511 to 1513.36 The numbers are not very great, but the pleadings are suggestive of a wider culture in which the preliminaries to marriage were eminently negotiable and in which serial relationships and perhaps even trial marriages – in the sense of a medium-term sexual relationship – were possible. It may be that a certain degree of flexibility or negotiability was, in fact, necessary and helpful: the declining observance of officially sanctioned marriage practices in the late seventeenth century could have been a reaction to a more rigid system whose assumptions – permanence, non-negotiability, patriarchal authority and economic responsibility, wifely subservience – were not in tune with the realities of contemporary urban life. Wunderli indeed speculated that some of the validation of marriage suits in the pre-Reformation period might have been ‘informal divorce cases from previous spouses’, that the parties were seeking to exclude claims based on a prior relationship by obtaining a ruling that a valid marriage existed with the present partner.37

Formal divorce was nevertheless impossible if a valid contract existed.38 Because marriage had to be entered into freely, the allegation of compulsion was grounds to query its validity. In 1475 William Rote sought an annulment of his contract with Agnes Wellys because he said he had been forced into it at dagger-point by her angry father.39 It is not clear whether, in fact, he managed to have the contract annulled, but it seems hardly likely to have been a successful marriage. Only a small number of cases relate to the breakdown of unquestionably valid marriages – culminating in the expulsion of a wife from the matrimonial home or the formal suit (by the wife) for separation on grounds of cruelty. A wife had to be in justifiable fear of her life to obtain the court’s backing in such cases, but Eleanor Brownynge seems to have been able to demonstrate this. She was threatened once by her husband in a tavern in Lombard Street with a dagger and a witness said she jumped ‘the length of four men’ to escape from him. On a later occasion he pursued her down the street, brandishing a dagger and threatening to kill her. She was wearing only her tunic and had her hair loose and streaming behind her, suggesting a domestic dispute that had escalated out of control. Under these circumstances, although the courts could not divorce the couple they could enjoin a legal separation and ensure that the wife received at least some of the assets of the marriage.40

While the church court records cannot show, or at least not directly, how many people, finding themselves in unbearable but indissoluble marriages, simply walked away from them, as they may have done in the seventeenth century,41 there is certainly evidence for marital disharmony and alienated affections. A large number of suits brought before the church courts in the late middle ages concerned adultery, sexual relations between a married woman and another man. Numbers varied by year, but the commissary court heard 506 adultery cases in the two years 1471 to 1472, 603 in eighteen months in 1492 to 1493. Not all of these came from metropolitan London, but the great majority did. The number of cases relative to the population of London seems quite high – in a city of approximately 40–50,000 people around 1500 there could have been 12–15,000 married couples – and obviously by no means all instances of adultery led to prosecution. Adultery cases formed a higher proportion of all cases in London than in the rural deaneries of Middlesex and Barking.42 It seems to have been a common belief that the presence of foreigners (often single males travelling on some kind of business) and the numerous unemployed or underemployed clergy who thronged London made a significant contribution to the level of illicit sexual activity in the city. The fifteenth-century visitation articles of the bishop or ordinary included the pessimistic enquiry, ‘whether the parson, vicar or chaplains … be incontinent or defamed with any woman, namely with any wedded woman, or have in parsonage or any other house, woman suspect’.43 Priests were indeed quite often in the dock, though it appears that the church courts were more lenient with them than the secular courts, which were also taking a hand in such cases.

Wunderli shows that although adultery cases ‘flooded the court’ in the late fifteenth century, conviction rates were low. Conviction entailed the enforcement of punishment, penance and/or compensation or child support, but even if few were convicted, adultery prosecutions served a social purpose. Norms and sanctions had been declared and their observation probably supported. It is notable that not all adultery suits were instance cases brought by the injured party: some were brought by neighbours or instituted on grounds of common fame, again suggesting that it was collective norms, not just the rights of a particular spouse, that were at issue.44

Fornication was not such a serious ‘crime’, but the victim, if any, was again society; it was usually society that prosecuted. A few couples were apparently reported for having sex between making a marriage contract and solemnizing it in church. This seems to have been a ‘crime’ created by the Church’s increasing insistence on solemnization in church as the critical event in making a marriage.45 More common, however, was fornication between couples who had no intention of marrying. Some long-term relationships between priests and women – concubinage or living in sin, rather than casual sexual encounters – also came to light. But fornication prosecutions were only about half as common as adultery suits: in 1471–2 there were 266 fornication cases as opposed to 506 adultery; in 1492–3, 263 fornication as opposed to 603 adultery. Conviction rates were again low, though higher than for adultery, perhaps because more of the accused were prepared to confess.46 However, while ‘respectable’ Londoners clearly used the courts and legal processes to help enforce communal norms, it does not appear that it was the middling sort imposing their moral judgment on the poor, as may have been the case in the seventeenth-century reformation of manners campaigns.47 Paupers, in fact, were rarely prosecuted in these courts; and while there was certainly strong sanction against insulting or slandering the city’s rulers, people of many ranks were accused of sexual misconduct: citizens, merchants and even an alderman.48

The wardmote inquest was an important forum in which sexual misdemeanours came to light and it shows us the level of local interest in the activities of neighbours. The articles of the inquest, recorded in the early fifteenth century, required the jury to present ‘any woman of lewd life or common scold or common bawd or courtesan … resident in the ward’.49 The wardmen of Aldersgate responded in 1510 with a string of complaints against Nicholas Browne for keeping misrule in his house, both men and women. They claimed that his wife was a ‘mis-woman of her body’, that priests and courtiers resorted to his house at unlawful hours in the night and that he kept a ‘quen’ (quean, harlot) in his house. They presented Lovington’s wife for keeping a married woman in her house to whom Laurence Micholl, a married man, resorted. Master Swafield – a name that implies some social standing – was suspected of keeping ill rule in his own house with a certain woman with whom he had had an illegitimate child some time previously. Stephen Watts was said to have two wives, one in Cornwall and the other in the parish of St. Anne Aldersgate.50 These accusations run the gamut from misrule to professional bawdry, from bastard-bearing to bigamy. Presentments made at the wardmote could be taken up as office cases in the church courts but, as noted above, it is unlikely that many, let alone all, of these offences were successfully prosecuted.

Another source of evidence was simple gossip and tale-bearing. John Palmer happened upon William Stevenes and Juliana Saunder in bed one afternoon in August 1471 and told the story to the parish chaplain, to the holy-water clerk of the church, to the priest of another parish, the wardmote inquest ‘and others’; and he may also have deposed in writing to the commissary court. But prosecution sparked by ill fame is complemented by the other great business of the church courts, defamation and especially sexual slander, and in fact John Palmer came to court as defendant in a slander case brought by William Stevenes, not as a prosecutor.51 Common fame or rumour was a real, almost tangible thing that in itself justified interference or even indictment, but, equally, individuals could defend their own fame by bringing prosecutions for slander against those who spread ill-reports of them. Laura Gowing has illuminated the world of sexual slander in Elizabethan London;52 the contest between honour and defamation was still very much a part of London life in the later seventeenth century, but it was already an active area in the fifteenth.

Defamatory words had in principle to be spoken maliciously and against someone not already of ill fame; and to accuse him or her of a crime or punishable offence. Sexual slanders made up a high proportion of cases: in 1493, 116 of 143 defamation cases were wholly or partly centred on sexual slanders. Plaintiffs cited what may seem casual insults shouted in the street – ‘strong whore’, ‘strong harlot’, ‘priest’s whore’ – and more detailed and specific accusations – ‘this is where you did it’, ‘you have a child in your belly if ever I had one’ – and, of course, the gossipers. A woman accused in this way was literally devalued in the marriage market, while a man was defamed if his wife was accused of bawdry or adultery, as much as if he himself were.53 Defamation cases illustrate the interaction of a number of issues: the importance of a person’s name and public perception; the construction of a woman’s honour as primarily sexual and of a man’s as encompassing the sexual behaviour of his wife; the sometimes aggressive moral surveillance of neighbours, arising from the sense of a common ownership of moral values; and what Wunderli refers to as ‘pre-Reformation Londoners’ … great … concern … with sexual norms and sexual misbehaviour’.54

The high proportion of sexual misdemeanours and sexual slanders among the cases heard by the church courts in late medieval London could be interpreted as evidence of a society in moral disarray in which standards were lax and misconduct common; or as one successfully policing itself. The latter seems more likely; and that these prosecutions served a useful purpose in proclaiming and supporting moral norms without, it would appear, being overly punitive or repressive. A large number of cases were inconclusive; convicted offenders were appropriately but not severely punished. Public penance, compensation and apology allowed the contrite to purge an offence and resume normal life. Londoners used the legal options available to them in a number of instrumental ways, exploiting the process to their own ends to confirm a marriage, exclude rival claims and assert their honour against impeachment.

However, the church courts dealt also with more professional forms of sexual misconduct. Casual fornication and adultery shaded into bawdry and prostitution. In defamation cases it is not clear whether calling someone a whore implied she was a common prostitute or just unchaste, but in some cases specific allegations of procuring and prostitution had been made. The city’s wardmote articles obviously assumed a connection, or perhaps a slippery slope, between individual unchastity and professional prostitution, indicting ‘any woman of lewd life or common scold or common bawd or courtesan’.55 The city’s leaders believed that professional prostitutes contaminated ordinary people. In a vehement proclamation against ‘the stynkyng and horrible Synne of Lechery’ in 1483, they charged ‘Strumpettes mysguyded and idil women daily vagraunt and walkyng about by the streetes and lanes of this said Citee of London and suburbes of the same’ with ‘provokyng many othere persones unto the said Synne of Lechery’. Men and women heretofore ‘weldisposed, daily fall to the said myschevous and horrible Synne’.56

These are strong words – and it is not the only time they are used – but in fact the prosecution of pimps and prostitutes seems to reveal the limits of moral policing in the metropolitan context. The church courts were notably unsuccessful either in obtaining convictions or in changing behaviour. Wunderli notes that of 1,030 individuals charged with procurement or bawdry in select years between 1471 and 1513, only seven confessed, but a larger number were suspended or excommunicated for contumacy. Prosecution of prostitutes was hardly more successful. Only ten prostitutes confessed out of 377 accused.57 Wunderli’s description of the life of pimp and prostitute Mariona Wood, frequently charged but never in practice inhibited from plying her trade in Portsoken over seventeen years, indicates how ineffective the court’s sanctions were.58 Contemporaries and, indeed, the seventeenth-century moralists might have characterized her as immoral and incorrigible; modern readers might consider economic necessity, desperation or a lack of alternatives as part of the picture. Wunderli argues that the high failure rate of prosecutions in the church courts may indicate that Londoners were turning to secular courts to police sexual offences,59 but perhaps they merely felt that having denounced bad characters to the wardmote inquest they had done their bit and the responsibility now lay elsewhere. Nevertheless, when someone was punished, it was exemplary and seemingly memorable. The Great Chronicle recorded in February 1500 that a flax-wife named Margaret Clitherow was set in the pillory in Cornhill for a common bawd ‘and aftir banished the toun for evyr’.60

The city on the whole preferred to export troublemakers rather than reform them. Its remedy for the plague of strumpets was to drive them from the city and to forbid anyone to harbour them. In effect, they marginalized the problem and, as is well known, the suburbs of London harboured numerous stews and brothels, from Cock Lane in the west to Portsoken in the east and especially south of the river. There were eighteen or more stewhouses or brothels in Southwark in 1506 and the bishop of Winchester’s court- and pipe-rolls of the turn of the century record numerous presentations and fines – effectively, licences to operate – of stewholders, pimps and singlewomen.61 The Great Chronicle records that in 1506 ‘the stews or common bordell beyond the water, for what hap or consideration the certainty I know not, was for a season inhibited and closed up. But it was not long before they were set open again’.62 Southwark remained a place of sexual opportunity and ill fame and a source of complaint and anxiety to the city, but, as the final closure of the stews in 1546 demonstrated, metropolitan prostitution was not to be suppressed by edict or ordinary prosecution.

Early Tudor Londoners’ sexual lives and marital relations were, therefore, as complicated as in any era, but problems, it appears, were contained. There was widespread respect for marriage and observance of its restrictions, as well as acknowledgement of authority, both domestic and civic. Norms were proclaimed and sometimes enforced, but the system had many loopholes. Concern about sexual misdemeanours and some enthusiasm for policing the behaviour of others were accompanied and moderated by readiness to compromise and seek conciliation – or, in the case of prostitution, by reluctance to push the process to the utmost.

Mortality

In the fifteenth century as well as in the seventeenth, however, human agency was not the only factor shaping the experience of marriage and family life. The harsh realities of disease and death were constantly reshaping the metropolitan population. Even when marriages were comparatively happy and settled, they were still fragile and often short-lived and the likelihood of bringing a whole family of offspring to adulthood – or of living to see that – was limited.

Despite recurrences of the sweating sickness and plague, London in 1500 was probably a safer place to live than it was in 1700, when both had disappeared. It seems probable that from 1540 to the 1640s ‘at least in the absence of plague London may have been able to maintain a balanced demography’ in that, epidemics apart, births matched or occasionally exceeded deaths, though probably not by a great deal.63 This ‘balanced’ phase probably began much earlier than 1540. The historical demographer Roger Finlay pointed to evidence for deteriorating life expectancy in London over the course of the seventeenth century.64 Explosive population growth entailed increased settlement densities, more overcrowding and poorer accommodation and environmental quality, but a range of other factors also contributed: increasing levels of poverty; the susceptibility of migrants to urban diseases; child-care practices such as wet-nursing; perhaps also health policies in relation to plague. Changing patterns of disease must also be considered, as smallpox and respiratory diseases became major killers, the latter plausibly linked to deteriorating air quality.

In the late seventeenth century, for every well-recorded long-term marriage – immortalized on monuments or by contemporaries or descendants – there were numerous unions cut short by death and often leaving no descent. We cannot calculate the duration of most marriages before the advent of parochial registration in 1538, but there is plenty of evidence for turnover: testators who mention two or more spouses; individual cases where a sequence of marriages is documented; more tangentially the evidence of the city’s orphanage court. The case studies in Caroline Barron’s and Anne Sutton’s Medieval London Widows included women who married two, three or even four times and some of these marriages were very brief. Thomasyne Percyvale’s first marriage, for example, probably lasted not more than three or four years; her second, less than a year, though her third lasted over thirty years.65 In a sample of fifty-five wills of Londoners proved in the commissary court of London in 1499–1500, at least five male testators had been married more than once. It is possible that the numbers of second or third marriages were higher, since it is not always clear whether a reference is to a deceased wife or wives and some deceased spouses may simply have been omitted.66 Remarriage, if it took place, was often quite speedy: Barbara Hanawalt found that over half of citizens’ widows with under-age children (subject, therefore, to the jurisdiction of the city’s court of orphans) between 1309 and 1458 had remarried by the time they came before the court to give surety for their children’s estates, usually within a year.67 John Bishop buried his wife in the Pardon Churchyard of St. Dunstan in the East in late 1495; before midsummer 1496 ‘John Byschoppe’s odyr wyffe’ was buried there too.68 Though remarriage was frequent, widowhood could be a very long-term state. The married life of some of Barron’s and Sutton’s medieval London widows formed only a short fraction of their life span. Thirteen widows experienced on average twenty-six years of widowhood; five were widows for over thirty years; and one for as long as fifty-nine years.69 Widows certainly formed a significant proportion of London’s population in the fifteenth century, as they did in the seventeenth.

One feature resulting in part from the short duration of many marriages was an overall low fertility rate. Even with speedy remarriage – which cannot always have been the case – a woman’s childbearing potential was interrupted and the survival of children who lost a father or mother must have been compromised. In the seventeenth century the statistician Gregory King noted that ‘each marriage in London produceth fewer people than in the country’. He attributed this in part to ‘the more frequent fornications and adulteries’ and ‘a greater luxury and intemperance’, as well as ‘a greater intenseness of business’, implying that this was in some way a moral failure, not just a natural consequence of urban mortality. His conclusion, however – and the tone in which he expressed it – echoed the lament of William Caxton that ‘in this noble cyte of london it [a family name and lineage] can unnethe contynue unto the thryd heyre or scarcely to the second’, even though in other cities families could trace their lineage back ‘for v or vi hondred yere and somme a thousand’.70

Although examples of large families are easily found in wills, memorials and orphanage cases, individual chances of survival were evidently low. Levels of infant mortality are impossible to trace before the age of baptismal registration, but the urban penalty – increased mortality in even quite modest centres of population – means that they were unlikely to be significantly better than those prevailing a century later, when nearly half of all children born in London did not survive to age fifteen.71

Wills are not a reliable source for assessing medieval child mortality, though quite a few do mention the burial-place of ‘my children’. But we can obtain some impression of the scale of mortality from parish accounts, at least in those parishes where the parish received something for all or most burials. In the single surviving lightwardens’ account for St. Andrew Holborn parish for 1477–8, twenty-eight burials are noted, possibly a little low for a parish of that size. At least ten of these were children: Arnold’s child, Herry Prank’s child, Milnepelle’s son, the weaver’s child in Gray’s Inn Lane.72 In St. Dunstan in the East the churchwardens’ accounts for 1498–9 record payments for five adult burials and four children: three fathers paid to bury their children in the Pardon Churchyard and a fourth for a torch for the burial of his child. In 1500–1 eleven adult burials are recorded and five children. One of the fathers, Master Ysak (Isaac), paid also for a four-hour knell of the great bell at 3s 4d. Isaac buried another child in 1502–3; and Master Tate, who had buried one child in 1500–1, buried his eldest son in 1501–2.73 Longer runs of accounts also show the repeated toll on individual families. The records of St. Mary at Hill, which seem to be very full, noted that John Clerk or Clark buried a daughter in 1477–9 and three children in 1487–8. Harry Vavasour buried a child in 1489; his wife paid for the burial of a son and one of his servants in 1492–3. John Awthorpe, churchwarden in 1501–2, recorded the receipt of 6s ‘of me, John Awthope, for the burial of 3 of myn owne chyldryn’.74

The inevitability of child mortality was implicitly acknowledged in the differential charges parishes made for burying them. Their smaller bodies took up less room and it was common to charge half the adult rate for the laystalls or burial-places of children. In 1498–9 St. Mary at Hill determined that the clerk should receive 8d for making a grave in their Pardon Churchyard for a man and 4d for a child.75 St. Mary Woolchurch charged half price in church for children and 4d, as opposed to 6d, in the churchyard;76 St. Martin Outwich in 1545 set its rate for a grave at 8d for adults and 4d for ‘Innocents’.77 St. Mary at Hill also authorized the clerk to take 4d for a knell of the little bell for a child and 8d for an adult, but St. Mary Woolchurch charged 4d for a knell of the least bell ‘for man woman or child’.78 But the fact that we do have records of children’s burial in more privileged places, or with lights, torches and bells, demonstrates that even a high rate of child mortality did not lead to indifference or casual disregard.

Records of the city’s orphanage procedures offer a complementary perspective on survival rates. For the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries together, Barbara Hanawalt calculated that of 631 city orphans whose fate is known, thirty-three per cent died under age.79 Of eight children orphaned in 1495, for example, only five survived to adulthood. Elias and Elena, orphans of Richard Bodley, late grocer, came of age or married, but their brother John died under age; Richard and Alice, orphans of Richard Dakers, late tailor, survived, but their sister Elizabeth died; Agnes, daughter of William Tenacres, survived and inherited her brother William’s share of their father’s estate when he died under age.80 Fathers often – with pessimistic realism – provided for the possibility that their heirs might die under age, arranging that the children should be each other’s heir, or that a proportion of a deceased child’s legacy should be devoted to pious uses. Henry Patenson left his daughter Elizabeth 10 marks for her marriage; if she died under age, it was to go to her brother, but if he too died under age Henry’s wife Elizabeth was to have half and spend the remainder on a chalice and paten to be given to Our Lady of Walsingham for prayers.81

The end result of this mortality of children, as Caxton noted, was that London’s population – and he surely meant the established, noteworthy families – was not reproducing itself in the male line. Family names died out, something that is easily visible in lists of aldermen, for example. Sylvia Thrupp calculated that medieval London merchants – surely the most favoured class demographically – left on average only one direct male heir and that fewer than eighty-five per cent of these lived long enough to have a chance of reproducing themselves.82 Of 141 lay testators in the consistory court of London in the early to mid sixteenth century, only forty per cent mentioned their own children in their testaments.83 It is possible that fewer than half of all marriages resulted in surviving offspring. London was growing between 1450 and 1550 by migration and not by natural increase.

Consideration of the family in medieval or early modern London has to take account of the immense impact of migration. The influx of young men skewed the age- and sex-distribution of the capital’s population considerably and the large numbers of apprentices contributed to problems of order. Apprentices participated in anti-alien riots in the fifteenth century and in the disturbances of Evil May Day in 1517 (when their targets included brothels).84 But they were firmly – if not inescapably – bound into structures of authority and patriarchal discipline and integrated into the households of their masters. And in a society that was hardly producing enough children of its own, they filled both an economic and an emotional need.

A great many men and women in later medieval London had no lineal descendants to whom to pass their skills and business capital and needed to find other ways of transmitting them to the next generation. It is not surprising that other kinds of relationship – collateral descent, kinship and apprenticeship – figured largely in the inter-generational transmission of skills and capital. The most significant of these was the master-apprentice one, a surrogate father-son relationship explicitly centred on the transmission of skills and work opportunity. More common than the bequest of tools and goods to any family member was the bequest to a servant or apprentice. Often a widow inherited and continued her late husband’s business; she would then be the one to pass it on to the apprentice. One widow specified that her apprentice be allowed to choose his own master and to have the shop, tools and his chamber for a year; another left the apprentice the use of her house and hangings. And apprentices were often held in affection, bequeathed personal goods other than tools and in many ways regarded as inheriting the persona of the deceased master.85 Members of the family in the sense of the household unit, they also became part of the family in a more literal sense. Henry Lussher left 10 marks ‘in good and sufficient wares’ to ‘John Dane which was my apprentice and now is my servant and to Alice Rumbold daughter to my wife if they be complet together as man and wife in way of marriage’.86 John Robotom, draper, left 20s to each of his six children under age and 20s to his apprentice when he came out of his years. All the residue, including presumably his stock, debts and other capital, he left to his wife Dorothy.87 Just a year after his death, however, Dorothy, apparently by then some three months pregnant, married the former apprentice, now himself a master.88

Parents lost children, but, as already implied, children lost parents, too. Many wills indicate that the children named were under age; and the city’s court of orphans had an important role to play in safeguarding the inheritance and wellbeing of the children of deceased citizens. The court’s very existence was an acknowledgement of the fragility of life and that many fathers would not see their children grow to adulthood. Thrupp calculated that of ninety-seven merchants who died between 1448 and 1520, the median age at death was forty-nine to fifty.89 Since a man could not marry until he came out of his apprenticeship, normally in his mid twenties, and would probably not have done so immediately, it is very likely that some of his children – if he had any – would still be under twenty-one by the time he reached fifty.

The under-age or unmarried children of a deceased citizen came under the protection of the common serjeant, who inventoried their inheritance, committed it and the children to one or more guardians and took bonds for the repayment of the estate when the children should come of age or marry. Orphanage business takes up an enormous amount of the city’s recorded activity, since bonds and custody awards were regularly registered in the city’s main record books, the Letter Books. Between 1470 and 1497 the aldermen dealt with orphanage matters on 315 occasions (relating to perhaps a hundred families); between 1500 and 1530 they accepted 620 recognizances (relating to perhaps 300 families). The pressure of business is reflected in the establishment in 1492 of a formal annual meeting to review and reaffirm the sureties for the orphans’ estates.90 Orphans were often committed to their mother, with or without a second husband. In due course, either the orphan himself or a female orphan’s husband acknowledged receipt of the inheritance. The situation offered opportunities for exploitation, either of the inheritance or of the child, but the city was a fairly careful guardian. Children could not be made wards of someone in the line of inheritance, who might have an interest in their death. It was forbidden to marry a city orphan without the city’s permission, presumably to prevent heirs being forced into disadvantageous and exploitative contracts and simple misalliance.91 The majority of marriages sanctioned by the city for the daughters of deceased merchants were to men of the merchant class or above.92

Paternal anxiety is expressed, not only in provision for the deaths of some or all of the children but in identifying a suitable guardian or in charging the widow to look after them. Henry Elveden noted in 1498 that he and his wife Joyce had three children ‘of our twey bodies lawfully begotten’ in nine years of marriage (though only two seem to have survived): he desired Joyce to be ‘specially good mother to [them], to help them after her power’.93 Most men with under-age children left a widow, even if she was not the children’s mother; in some cases there was an adult brother or sister who may have been expected to take an interest. Because married women so rarely made wills, we have little sense of their emotions on leaving their children to the care of their father or even to a stepfather. Elinor Fynimor (d. 1500) probably expected her parents, both of whom were still alive, to take care of her son, to whom she left the residue of her goods ‘to find him to school’. She did not call herself a widow or mention a husband, which could imply that she was unmarried, in which case the choice of parents seems natural.94

Comparatively few widow testators seem to have left underage children, which may be an indication of the likelihood, even necessity, of remarriage for such women. As Hanawalt noted, use of the child’s patrimony while it was under age would certainly have been an attraction to a second husband.95 Dying husbands rarely took steps to impede their wife’s remarriage and city companies probably encouraged widows to remarry within the craft to maintain its solidarity and wealth. But it may in any case have been that young widowed mothers, whose children were under the supervision of the court of orphans, did not need to make a will for the settlement of their estate.

One striking phenomenon in seventeenth-century London was the large number of single-parent households. In one parish in 1695, for example, St. Katherine Coleman, there were numerous partial or broken families. Fifteen households with children were headed by widows or single women and three by single men, while fourteen widows or single women lodgers and two single male lodgers had children. Single parents made up over twenty per cent of all parents.96 This was well above the mean for the city as a whole, but there is a strong likelihood that single parenthood was an increasing feature of city life in the seventeenth century as marriages fractured or dissolved under stress and remarriage became less common. There is no comparable source for the 1490s, but it seems unlikely that this was such a problem then. It seems rare for widowed men and women, at least of the middling or citizen sort, to remain single for long if they had young children. Either they remarried or, perhaps equally often, the child or children may not have survived.

Another problem in the late seventeenth century that may be specific to that period was child abandonment. This was probably a long-running issue in early modern London, but it seemed to be spiralling out of control in the 1680s and 1690s: Valerie Fildes estimated that approximately 1,000 children a year were abandoned in London in the 1690s.This huge problem seems to have been the result of increasing poverty, broken families (warfare made a serious contribution) and the stresses of urban life.97 Though neither poverty nor distress was absent from London in 1500, if the capital was both economically buoyant and struggling to reproduce itself there may not have been so many unwanted births. There seems also to have been a culture of care, perhaps because the problem was manageable. Londoners internalized the Church’s exhortation to perform works of corporal mercy and to care for the widow and orphan; and it is striking how many instances of effective adoption of poor children or alms children are brought up in even a brief trawl of wills and biographies. John Clovier in 1495 left a pair of sheets and 6s 8d to ‘a young child found by me of alms called after my name’;98 Thomas Portar left 3s 4d to ‘my poor child’ in 1500.99 The anonymity of these children is perhaps a little chilling, but the wealthy widow Alice Claver (d. 1489) left 40s each to Alice ‘my mayde that was gevyn me to find of almes’ and Edward ‘whom I find in almes for Goddis sake called my childe’.100 Thomasyne Percyvale was bringing up five such children at the time she made her will in 1503. The boys were to be educated for the Church or apprenticed; the girls were to be bound to good masters at the age of fourteen, but in the meantime, all were to be provided with ‘mete drynk and lernyng’.101

Crisis or Coping?

The issues discussed above – marital irregularities, sexual misconduct, the mortality of parents and children – might well suggest that the family in London was under quite serious stress in 1500. But in most of these cases it appears that the problem was limited or mitigated in some way. The family provided a flexible and enduring structure in London society; and late medieval Londoners responded to the strains under which they lived by strengthening the connections that existed and forging new relationships. ‘Family values’ cannot be equated with a hard-and-fast patriarchal family unit, with an insistence on ‘real’ or biological parents and a propensity to view anything less as dysfunctional. They were expressed in a more collaborative and supportive networking. London custom supported family values of this kind in the sense that it accepted the fragility of the nuclear unit and sought to mitigate the effects of that fragility. The ‘custom of London’ had several different connotations, but it specifically protected both widow and children against disinheritance, insisting that the unadvanced children should receive a one-third share of the estate and the widow likewise. It protected orphans against harm and exploitation and guaranteed their accession to their inheritance in due course. It guaranteed the widow’s future residence in the marital home beyond the meagre forty days offered by common law. The husting court heard pleas of dower and of execution of testament, which helped widows and heirs to obtain their rights against executors; widows’ claims for dower had a high rate of success. Although London had no official dowry fund as many European cities did, many Londoners included ‘poor maids’ marriages’ among their benefactions. In a different way, a familial or fraternal ideal was manifested in the numerous fraternities and brotherhoods in virtually every church in London, to which Londoners clearly attached great affection and importance.102

This article suggests that the London family was a loose and ever-changing nexus, both a domestic entity and a more extended network, providing vital support and continuity. If we read late medieval wills with pessimistic eyes, we are struck by the loss of husbands and wives, the feared deaths of children, the large proportion of marriages that produced no surviving issue. But if we are more optimistic, we can interpret the evidence in a more positive way. The premature death of a spouse or children was often followed by their replacement by surrogates. The London commissary court wills of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries document an array of significant relationships beyond the nuclear family. Testators named brothers, sisters, their spouses, their sons and daughters, cousins, the wife’s own children by a former marriage, her brothers and sisters and their children, even a deceased wife’s god-daughter. In several instances these were the heirs, not just casual beneficiaries; while one’s own issue was preferred, collateral descendants were acceptable substitutes. And the net stretched wider: alms children filled a gap in the households of older or childless parents. Godchildren were remembered; and the rector of St. Michael Bassishaw left legacies to two ‘spiritual sons’.103 And, as discussed above, apprentices filled an important gap in the affective as well as the business lives of Londoners.

However, even if later medieval London was resilient in the face of demographic and social stress, there was some continuity of concern over the centuries. The French visitor Henri Misson, in the late seventeenth century, commented that the English (and he evidently had most of his experience in London) were too affectionate and indulgent with their children, ‘always flattering, always correcting, always applauding what they do’, whereas ‘to keep them in awe is the best way to give them a good turn in their youth’.104 But 200 earlier William Caxton had lamented that although London children started out well – ‘fare ne wyser ne bet bespoken children in theyre yongthe ben nowher than there ben in london’, they did not turn out so: ‘at their full rypyng there is no carnel ne good corn founden, but chaffe for the moost parte’.105

Endnotes

- See also V. Harding, ‘Families and households in early modern London, c.1550–1640’, in The Oxford Handbook of the Age of Shakespeare, ed. M. Smuts (Oxford, 2017), pp. 596–615.

- G. King, ‘Natural and political observations upon the state and condition of England’ (1695), in Seventeenth-Century Economic Documents, ed. J. Thirsk and J. P. Cooper (Oxford, 1972), pp. 770–84, at p. 777; M. Kitch, ‘Capital and kingdom: migration to later Stuart London’, in London 1500–1700: the Making of the Metropolis, ed. A. L. Beier and R. Finlay (London, 1986), pp. 224–51, at pp. 224–5; R. B. Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex, c.1660–1725 (Cambridge, 1991), p. 15.

- E.g., A. Vickery, ‘Golden age to separate spheres?: a review of the categories and chronology of English women’s history’, Hist. Jour., xxxvi (1993), 383–414.

- Medieval London Widows, 1300–1500, ed. C. M. Barron and A. F. Sutton (London, 1994); also A. F. Sutton, Wives and Widows of Medieval London (Donington, 2016).

- R. Wunderli, London Church Courts and Society on the Eve of the Reformation (Cambridge, Mass., 1981); Love and Marriage in Late Medieval London, ed. S. McSheffrey (Kalamazoo, Mich., 1995); S. McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture in Late Medieval London (Philadelphia, Pa., 2006). See also R. A. Houlbrooke, Church Courts and the People during the English Reformation (Oxford, 1979); M. Ingram, Church Courts, Sex and Marriage in England, 1570–1640 (Cambridge, 1987); L. Giese, Courtships, Marriage Customs, and Shakespeare’s Comedies (New York and Basingstoke, 2006); and M. Ingram, Carnal Knowledge: Regulating Sex in England, 1470–1600 (Cambridge, 2017).

- Cal. Letter Bks. L; C. H. Carlton, The Court of Orphans (Leicester, 1974); B. A. Hanawalt, Growing up in Medieval London: the Experience of Childhood in History (Oxford, 1993).

- A. Dyer, Decline and Growth in English Towns, 1400–1640 (Basingstoke, 1991), pp. 56–9.

- C. M. Barron, London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People, 1200–1500 (Oxford, 2004), p. 45; V. Harding, ‘The population of London, 1550–1700: a review of the published evidence’, London Jour., xv (1990), 111–28.

- G. Rosser, Medieval Westminster, 1250–1540 (Oxford, 1989); London Bridge: Selected Accounts and Rentals, ed. V. Harding and L. Wright (London Rec. Soc., xxxi, 1994).

- D. Keene, Cheapside before the Great Fire (London, 1985); cf. D. J. Keene and V. Harding, Historical Gazetteer of London Before the Great Fire Cheapside; Parishes of All Hallows Honey Lane, St Martin Pomary, St Mary Le Bow, St Mary Colechurch and St Pancras Soper Lane (London, 1987), British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/london-gazetteer-pre-fire> [accessed 31 Oct. 2018].

- M. D. Lobel, The British Atlas of Historical Towns: the City of London from Prehistoric Times to c.1520, iii (2nd edn., Oxford, 1991). A new edition of the c.1520 map of London has recently been produced: A Map of Tudor London: England’s Greatest City in 1520 (Historic Towns Trust Town and City Historical Maps, Oxford, 2018).

- A Survey of London by John Stow, ed. C. L. Kingsford (2 vols., Oxford, 1908), i. 126.

- The Merchant Taylors’ Company of London: Court Minutes 1486–93, ed. M. Davies (Stamford, 2000), pp. 31–4; S. L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500 (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1948), pp. 389–92; J. Wareing, ‘Changes in the geographical distribution of the recruitment of apprentices to the London companies, 1486–1750’, Jour. Hist. Geog., vi (1980), 241–9.

- S. Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century London (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 78–9.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, p. 156; Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, pp. 31–6.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, pp. 203, 295, 302; Merchant Taylors’ Company of London: Court Minutes, p.40 and passim; Records of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, iii. Court Book, 1533–1573, ed. B. Marsh (Oxford, 1915), pp. 12, 15, 16.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, pp. 301–2 (quotation) and pp. 254, 284, 291, 294, 298, 306, 308, 312, 319–20; M. Davies, ‘Governors and governed: the practice of power in the Merchant Taylors’ Company in the fifteenth century’, in Guilds, Society and Economy in London, 1450–1800, ed. I. A. Gadd and P. Wallis (London, 2002), pp. 67–83, esp. pp. 74–6.

- Davies, Merchant Taylors’ Court Minutes, p. 31; Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, pp. 47–9, 53. By ‘London’s population’, Rappaport seems to have meant the city plus immediate suburbs but not the whole metropolis.

- S. Hovland, ‘Girls as apprentices in late medieval London’, in London and the Kingdom: Essays in Honour of Caroline M. Barron: Proceedings of the 2004 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. M. Davies and A. Prescott (Harlaxton Medieval Studies, n.s., xvi, Donington, 2008), pp. 179–94.

- For examples of female servants, see London Consistory Court Wills, 1492–1547, ed. I. Darlington (London Rec. Soc., iii. 1967), nos. 6, 7, 37, 114, 118, 130, 161, 178, 183, 184, 228, 232, 238. Cf. P. J. P Goldberg, ‘Marriage, migration, and servanthood: the York cause paper evidence’, in Woman is a Worthy Wight: Women in English Society, c.1200–1500, ed. P. J. P. Goldberg (Stroud, 1992), pp. 1–15; P. J. P. Goldberg, Women, Work, and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women in York and Yorkshire, c.1300–1520 (Oxford, 1992), pp. 195–202. Peter Earle argued that the changing nature of both men’s and women’s employment in the later 17th century increased the need for domestic service (P. Earle, A City Full of People: Men and Women of London 1650–1750 (London, 1994), pp. 110–3).

- England’s Export Trade, 1275–1547, ed. E. M. Carus-Wilson and O. Coleman (Oxford, 1963); B. Dietz, ‘Antwerp and London: the structure and balance of trade in the 1560s’, in Wealth and Power in Tudor England: Essays Presented to S. T. Bindoff, ed. E. W. Ives, R. J. Knecht and J. J. Scarisbrick (London, 1978), pp. 186–203; B. Dietz, ‘Overseas trade and metropolitan growth’, in Beier and Finlay, London 1500–1700, pp. 114–40.

- J. C. K. Cornwall, Wealth and Society in Early Sixteenth-Century England (London, 1988), pp. 64–5; Dyer, Decline and Growth, pp. 62–3.

- The average daily wage of the London craftsman in the period between 1457 and 1471 was 8d, the labourer’s 5d (Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, pp. 130–1).

- Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, p. 85.

- Corporation of London Journal, 11 (now LMA, COL/CC/01/01/011), fo. 337–8v, quoted by Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, pp. 168–9.

- Rappaport, Worlds within Worlds, p. 169; see also I. W. Archer, The Pursuit of Stability: Social Relations in Elizabethan London (Cambridge, 1991).

- C. Rawcliffe, Medicine and Society in Later Medieval England (Stroud, 1995), pp. 165, 169, 209–10.

- P . Slack, The Impact of Plague in Tudor and Stuart England (London, 1985), p. 147, although he warns that ‘the inadequacies of the probate evidence prohibit any attempt to measure the severity as well as the frequency of epidemics before 1540’ (p. 48).

- G. Thwaites, M. Taviner and V. Gant, ‘The English sweating sickness, 1485 to 1551’, New England Jour. Med., cccxxxvi (1997), 580–2.

- The Great Chronicle of London, ed. A. H. Thomas and I. Thornley (London, 1938), pp. 226, 294.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/8, fo. cciii.

- J. Boulton, ‘Itching after private marryings? Marriage customs in seventeenth-century London’, London Jour., xvi (1991), 15–34.

- McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, p. 21. For what follows the discussion leans heavily on R. Wunderli’s analysis of the church court proceedings in London Church Courts; and on S. McSheffrey’s useful edition of extracts from the cases in Love and Marriage.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp.56–9; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, pp. 40–1.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 59–65; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, pp. 92–3.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, p. 120. See also Giese, Courtships, Marriage Customs.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 120–1.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp.121–2.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 81–2; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, pp. 1–4.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 82–3; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, pp. 140–1.

- F . Dabhoiwala, ‘The pattern of sexual immorality in seventeenth and eighteenth-century London’, in Londinopolis: Essays in the Social and Cultural History of Early Modern London, ed. P.Griffiths and M. Jenner (Manchester, 2000), pp. 86–106.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 84–8.

- The Customs of London, Otherwise Known as Arnold’s Chronicle: Containing, among Divers Other Matters, the Original of the Celebrated Poem of The Nut-brown Maid, ed. F. Douce (London, 1811), p. 274.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 84–8.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 84–5; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, pp. 113, 160–1.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 88–92, 144–5.

- Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment, pp. 238–72; cf. M. Spufford, ‘Puritanism and social control’, in Order and Disorder in Early Modern England, ed. A. Fletcher and J. Stevenson (Cambridge, 1985), pp. 41–57.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, p. 44; McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 84–8.

- Liber Albus: the White Book of the City of London, compiled A.D. 1419, by J. Carpenter, Common Clerk, R. Whitington, Mayor, ed. H. T. Riley (London, 1861), pp. 290–2. Cf. CPMR 1413–37, pp. 117–41, pp. 150–9. See also Wunderli, London Church Courts; C. E. Berry, ‘Margins and marginality in fifteenth-century London’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2018).

- The Records of Two City Parishes: a Collection of Documents Illustrative of the History of SS. Anne and Agnes, Aldersgate, and St. John Zachary, London, from the Twelfth Century, ed. W. McMurray (London, 1925), pp. 29–30.

- McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 87–8; McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex and Civic Culture, p. 152.

- L. Gowing, Domestic Dangers: Women, Words and Sex in Early Modern London (Oxford, 1996).

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 76–80, 90; McSheffrey, Love and Marriage, pp. 86–7.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, p. 80.

- Riley, Liber Albus, pp. 290–2.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, p. 206.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 100–1, 146–7.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, p. 99.

- Wunderli, London Church Courts, pp. 101–2.

- Thomas and Thornley, Great Chronicle, p. 289.

- M. Carlin, Medieval Southwark (London, 1996), pp. 209–19; J. B. Post, ‘A fifteenth-century customary of the Southwark stews’, Jour. Soc. Archivists, v (1977), 418–28. Cf. R. M. Karras, Common Women: Prostitution and Sexuality in Medieval England (Oxford, 1996).

- Thomas and Thornley, Great Chronicle, p. 331.

- C. Galley, The Demography of Early Modern Towns: York in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Liverpool, 1998), pp. 16–7.

- R. Finlay, Population and Metropolis: the Demography of London 1580–1650 (Cambridge, 1981), p. 109.

- Barron and Sutton, Medieval London Widows, esp. M. Davies, ‘Dame Thomasine Percyvale, “The Maid of Week” (d. 1512)’, pp. 185–206; A. F. Sutton, ‘Serious money: the benefits of marriage in London, 1400–1499’, London Jour., xxxviii (2013), 1–17.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fos. 183–207.

- Hanawalt, Growing up in Medieval London, p. 96.

- LMA,P69/DUN1/B/001/MS04887, fo. 9v et. seqq.

- Barron and Sutton, Medieval London Widows, passim.

- The Prologues and Epilogues of William Caxton, ed. W. J. B. Crotch (Early English Text Soc., o.s., clxxvi, London, 1928), pp. 77–8.

- R. Finlay and B. Shearer, ‘Population growth and suburban expansion’, in Beier and Finlay, London 1500–1700, pp. 37–59, at pp. 49–50.

- C. M. Barron and J. Roscoe, ‘The medieval parish church of St Andrew Holborn’, London Topographical Record, xxiv (1980), 31–60, at pp. 56–7.

- LMA, P69/DUN1/B/001/MS04887, fo. 9v et seqq. Not all burials were liable for a fee, so the actual totals must be higher.

- Medieval Records of a London City Church, ed. H. Littlehales (Early English Text Soc., o.s., cxxviii, London, 1905), pp. 78, 128, 146, 183, 245.

- Littlehales, Medieval Records of a London City Church, p. 231.

- BL, Harley MS. 2252, fo. 164.

- LMA, P69//MTN3/B/004/MS06842, fo. 3 et seqq.

- Medieval Records of a London City Church, p. 231; BL, Harley MS. 2252, fo. 163.

- Hanawalt, Growing up in Medieval London, p. 57.

- Cal. Letter Bks. L, pp. 314–5.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 197v.

- Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London, pp. 199–200, 203.

- Darlington, London Consistory Court Wills, passim.

- Thomas and Thornley, Great Chronicle, p. 188; D. Wilson, ‘Evil May Day 1517’, History Today, lxvii (2017), 66–71.

- V. Harding, ‘Sons, apprentices, and successors in late medieval and early modern London: the transmission of skills and work opportunities’, in Generations in Towns, ed. F.-E. Eliassen and K. Szende (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 53–68.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 200v.

- Darlington, London Consistory Court Wills, no. 237.

- The Parish Registers of St Michael Cornhill, 1546–1754, ed. J. L. Chester (Harleian Soc., Register Section, vii, 1882), pp. 5, 74.

- Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London, p. 194.

- Carlton, Court of Orphans, pp. 20, 25, 36.

- Carlton, Court of Orphans, pp. 18–19. Cf. Cal. Letter Bks. I, p. 141.

- Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London, p. 28.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 192v.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/ MS09171/008, fo. 199.

- Hanawalt, Growing up in Medieval London, p. 96.

- LMA, COL/CHD/LA/04/01/042. See also D. V. Glass, ‘Introduction’, in London Inhabitants Within the Walls (London Rec. Soc., ii. 1966), pp. ix–xxxvii. For further analyses, see P. Baker and M. Merry, ‘“For the house, herself and one servant”: family and household in late seventeenth-century London’, London Jour., xxxiv (2009), 205–32.

- V. Fildes, ‘Maternal feelings re-assessed: child abandonment and neglect in London and Westminster, 1550–1800’, in Women as Mothers in Pre-industrial England: Essays in Memory of Dorothy McLaren, ed. V. Fildes (London, 1990), pp. 139–78.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 190v.

- LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 199v.

- A. F. Sutton, ‘Alice Claver, silkwoman (d. 1489)’, in Barron and Sutton, Medieval London Widows, pp. 129–42, at pp 138–9.

- Davies, ‘Thomasyne Percyvale’, p. 202.

- C. M. Barron, ‘The parish fraternities of medieval London’, in The Church in Pre-Reformation Society, ed. C. M. Barron and C. Harper-Bill (Woodbridge, 1985), pp. 13–37.

- Darlington, London Consistory Court Wills, nos. 46, 75, 77, 84, 148, 155, 187;LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/008, fo. 203.

- H. de Valbourg Misson, M. Misson’s Memoirs and Observations in his Travels over England … Dispos’d in Alphabeticall Order, Written originally in French and Translated by Mr Ozell (London, 1719), p. 33.

- Crotch, Prologues and Epilogues of William Caxton, pp. 77–8, quoted by Thrupp, in Merchant Class of Medieval London,p. 191.

Chapter 1 (11-36) from Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer (University of London Press, 10.31.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.