How did Renaissance writers and artists portray the European exploration of the Americas?

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. Kasey Evans

Graduate Program Faculty Director

Northwestern University

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 05.24.2012, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

In The Tempest, the “honest old councilor,” Gonzalo, imagines an ideal commonwealth in which there would be no private property, no magistrate, no labor, and no inequality of rank. Gonzalo’s description of a society in which “All things in common nature should produce” suggests just one of the ways in which Shakespeare adapted contemporary ideas about utopian societies. Although people had imagined ideal societies since at least the classical period, the term utopia first appeared less than one hundred years before Shakespeare wrote The Tempest. The English humanist, Thomas More, introduced the word in 1516 to name a fictional island that was the site of an ideal commonwealth. More devised utopia from Greek terms meaning “not a place” or “nowhere,” but he also provided his Utopia with a specific geography: he locates his fictional island in the New World.

More wrote Utopia just 24 years after Columbus’ arrival in the Caribbean, and his narrative suggests how European contact with the Americas provoked the imagination. It seemed to many Europeans that anything might be found in this New World, including human societies that were better organized than their own. More could not publish Utopia in England under the reign of Henry VIII—his imaginary society was too clearly an indictment of Henry’s England. But his book participated in, and helped to initiate, a Renaissance literary tradition that brought together the exploration of the Americas, the critique of European societies, and the desire to create better communities in which to live. This essay demonstrates some of the ways in which Renaissance writers and artists imagined the New World and its utopian possibilities.

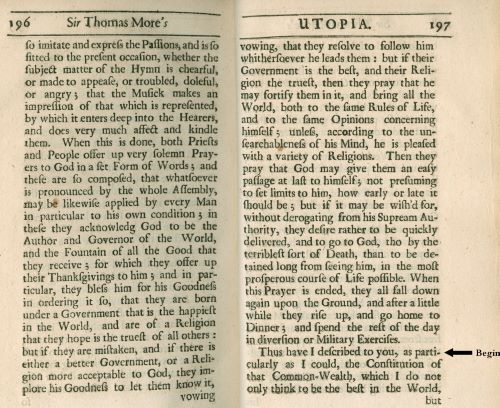

More’s Utopia

Thomas More wrote Utopia in Latin in 1516 and published it in Louvain, in present-day Belgium, in order to avoid political persecution in England. It was translated into English and printed in London 25 years later, after the death of Henry VIII. In Utopia, More imagined a member of Amerigo Vespucci’s expedition to the New World who becomes separated from the other Europeans and discovers the island of Utopia. On his return to Europe, he describes a society in which everyone lives for the common good, as determined through natural reason. Utopians are ruled by an elected magistrate. They have no private property or distinction of rank and no war. Everyone works, but only six hours a day. Men and women receive the same education and are free to practice the religion of their choice. In the passage that follows, the explorer contrasts Utopia with England.

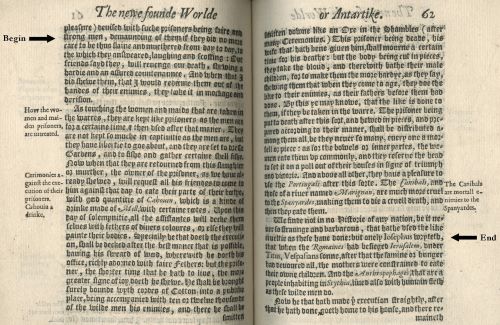

Cannibalism in the Americas

André Thevet was a sixteenth-century French explorer, priest, and cosmographer (one who maps the heavens and the earth). The New Found Worlde was first published in Paris in 1557. Thevet described the people, plants, and animals that he encountered in the region of present-day Brazil, where he traveled to help establish a French colony. He used the word antarctike in the title to mean “southern,” not necessarily the South Pole. In portraying the “Americans” or “wilde men,” as he called them, Thevet lingered on the customs that he knew European readers would find most shocking or strange. The passage included here describes the practice of eating prisoners of war and was probably a source for Michel de Montaigne’s essay “Of Cannibals.” At the opening (top left), Thevet has asked a prisoner whether he is not afraid to die this way.

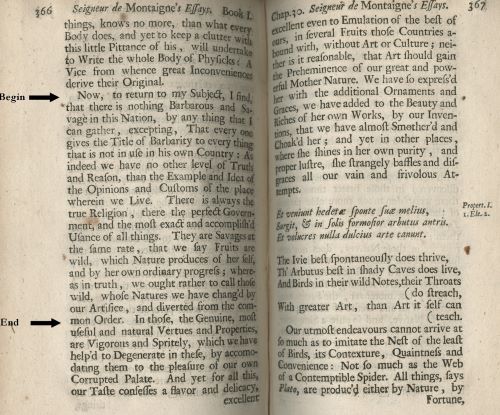

Montaigne’s “Noble Savage”

Michel de Montaigne’s influential Essays were first published in French in 1580 and were translated into English in 1603. They offered a wide-ranging investigation of institutions, beliefs, and customs. These excerpts from “Of Cannibals” present the classic formulation of the “noble savage.”

The New Found Land of Virginia

Thomas Hariot’s Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia is a promotional tract that first published in 1588. It was designed to encourage Englishmen to finance and to help settle Roanoke, the first English colony in North America. Hariot cataloged the natural produce found in Virginia before turning to the “nature and manners of the people,” whom he described as knowledgeable of the region, but also defenseless. They “are not to be feared,” he wrote, “but they shall have cause to feare and love us, that shall inhabite with them.”

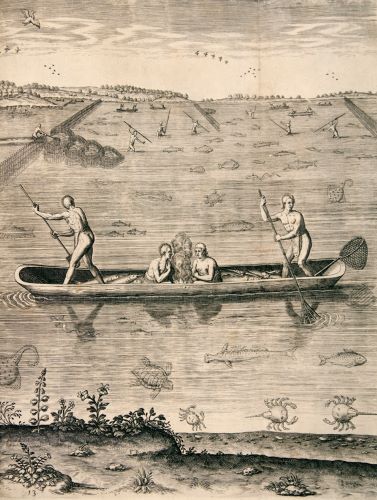

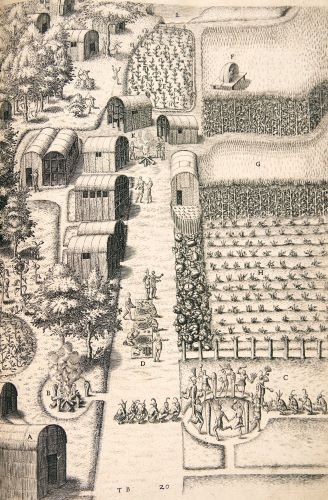

The Report was republished two years later, in four languages, with engravings by Theodor de Bry. It forms the first volume of de Bry’s series of books on the European exploration of the New World.

De Bry made these sketches of Algonkian fishermen and an Indigenous village based on the sketches by John White, who accompanied Thomas Hariot to the English settlement of Roanoke in Virginia.

The Spanish Conquest of the Caribbean

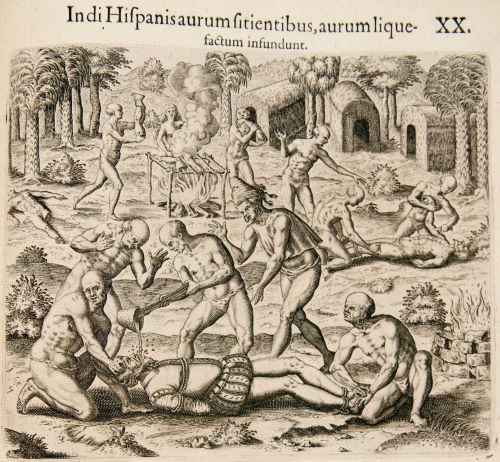

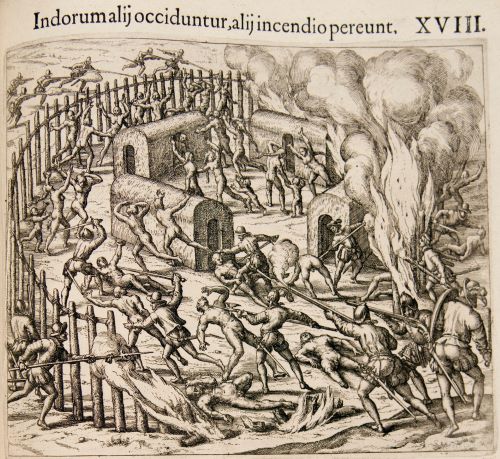

Theodor de Bry’s America is the fourth volume of a series titled Grandes Voyages. It was based on Giralamo Benzoni’s eyewitness account of the Spanish in Central and South America.

These engravings portray violence in the Caribbean, or West Indies, and are based on eyewitness accounts of the Spanish conquest.

Prospero’s Island

In the late eighteenth century, the London printer and engraver, John Boydell, commissioned artists to create paintings illustrating the works of Shakespeare. He then produced engravings based on their paintings and published them together with Shakespeare’s plays. This plate is based on a work by the Swiss-born Romantic painter Henry Fuseli. It depicts Miranda, Prospero, Ariel, and Caliban in Act I, scene ii, of The Tempest. In the text at the bottom, Prospero curses Caliban with cramps for his disobedience.