Early scientists were eager to use photographic technologies to learn more about the moon.

By Antares Wells

Curatorial Assistant

J. Paul Getty Museum

You’ve probably seen this photograph of the moon landing.

But what about the photos that came before it?

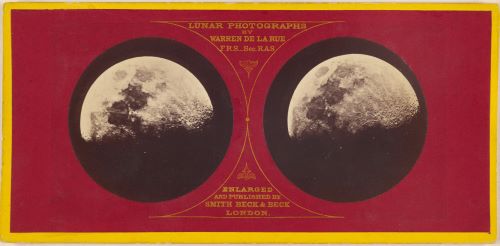

From the earliest days of photography, scientists were eager to use photographic technologies to learn more about the moon, the solar system, and the night sky.

They built telescopes that featured several lenses: one for observation, the other for making photographs. The idea? Photographs could help capture scientific phenomena that were invisible to the naked eye.

Photographs were also thought to provide a more accurate view than observations noted down by hand, without tiring out the eye muscles.

There were some limitations, though. For one, astronomers could only photograph when the sky was clear. Long exposure times and changing atmospheric conditions meant that many photographic plates were unusable.

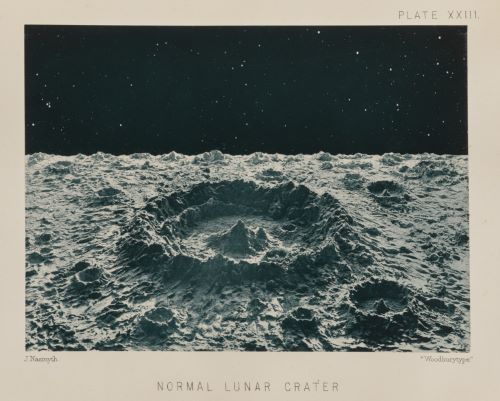

Unable to fully capture what they saw, some astronomers, such as Scottish scientists James Nasmyth and James Carpenter, created plaster models of the moon’s surface based on the view through a telescope. They then photographed the models in bright sunlight against black backdrops to simulate the lunar landscape.

Nasmyth and Carpenter used these photographs to illustrate their theories about the nature of the moon’s surface, in their book The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite.

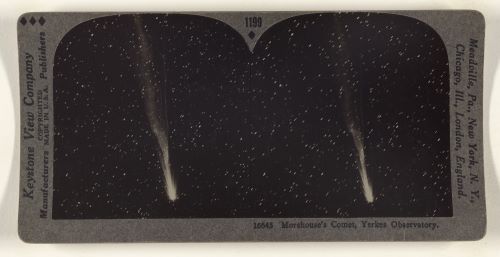

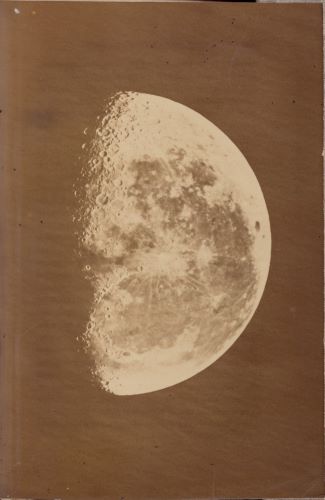

Despite technical challenges, photographers across the world managed to capture startlingly detailed photographs of the night sky.

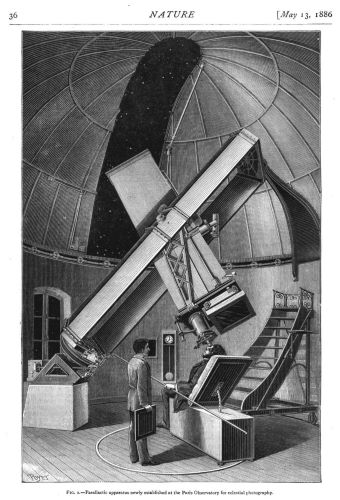

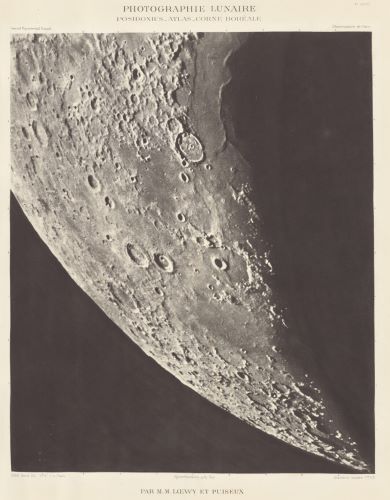

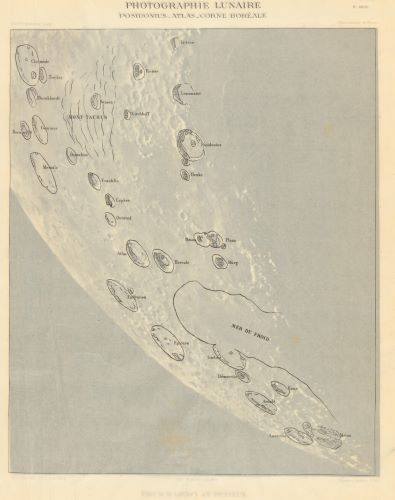

Running from 1887 to 1964, the Carte du Ciel (Map of the Sky) project created a vast photographic catalog of the stars, with 17 observatories participating—from Chile to Finland, Australia to Mexico. In a similar vein, astronomers Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux, at the Paris Observatory, sought to map the moon in their work The Photographic Atlas of the Moon.

Starting in 1894, they photographed the moon every clear night for 14 years through a refractor telescope. The published images were overlaid with tissue that mapped the topographic features of the moon.

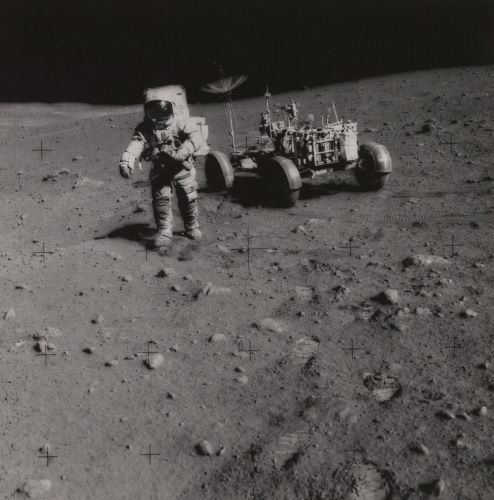

Many of these detailed photographs remained reference points for astronomers right up until the mid-20th century, when the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union led to lunar images of increasing clarity.

And, ultimately, the ability to take a photograph from the surface of the moon itself!

Originally published by The Iris, 06.18.2023 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.